Sindhi language

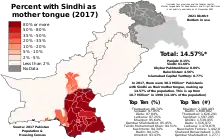

Sindhi (English pronunciation: /ˈsɪndi/;[5] Naskh: سنڌي, Nastaliq: سنڌي, Sindhi pronunciation: [sɪndʱiː]) is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in the region of Sindh and Balochistan by the Sindhi people. The language is a mix of Devanagari and Persoarabic script. It is the official language of the Pakistani province of Sindh[2][3][4] and spoken in North Gujarat (Kutch, Ahmedabad, and Gandhinagar) and Southwestern Rajasthan in India, where it does not have any state-level status.[6][7] As of the 2017 census in Pakistan, Sindhi is the first language of 30.26 million people, or 14.57% of the country's population.[8] In India, it was the first language of 1.68 million as of the 2011 census.[9][lower-alpha 2]

| Sindhi | |

|---|---|

| Sindi | |

| سنڌي | |

Sindhi written in Perso-Arabic script | |

| Native to | Pakistan and India |

| Region | Sindh and Balochistan (Pakistan) Kutch-Jaisalmer (India) |

| Ethnicity | Sindhis |

Native speakers | c. 32 million (2017)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Perso-Arabic (Naskh), Devanagari (India) and others | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | sd |

| ISO 639-2 | snd |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:snd – Sindhilss – Lasisbn – Sindhi Bhil |

| Glottolog | sind1272 Sindhisind1270 Sindhi Bhillasi1242 Lasi |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-f |

The proportion of people with Sindhi as their mother tongue in each Pakistani District as of the 2017 Pakistan Census | |

Sindhi is not in the category of endangered according to the classification system of the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

|

| Constitutionally recognised languages of India |

|---|

| Category |

| Official Languages of the Indian Republic |

| Related |

|

Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India Official Languages Commission Languages by number of native speakers |

|

Sindhi has an attested history from the 10th century CE, before which it is unclear how it relates to local varieties of Middle Indo-Aryan languages. Sindhi was one of the first languages of South Asia to encounter influence from Persian and Arabic following the Umayyad conquest in 712 CE. A substantial body of Sindhi literature developed during the Medieval period, the most famous of which is the religious and mystic poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai from the 18th century. Modern Sindhi was promoted under British rule beginning in 1843, which led to the current status of the language in independent Pakistan after 1947.

History

Origins

The name "Sindhi" is derived from the Sanskrit sindhu, the original name of the Indus River and the surrounding region, which is where Sindhi is spoken.[10]

Like other languages of the Indo-Aryan family, Sindhi is descended from Old Indo-Aryan (Sanskrit) via Middle Indo-Aryan (Pali, secondary Prakrits, and Apabhramsha). 20th century Western scholars such as George Abraham Grierson believed that Sindhi descended specifically from the Vrācaḍa dialect of Apabhramsha (described by Markandeya as being spoken in Sindhu-deśa, corresponding to modern Sindh) but later work has shown this to be unlikely.[11]

Early Sindhi (10th–16th centuries)

Sindhi entered the New Indo-Aryan stage around the 10th century CE.[12][13] However, literary attestion of Sindhi from this period is sparse; early Isma'ili religious literature and poetry in India, as old as the 11th century CE, used a language that was closely related to Sindhi and Gujarati. Much of this work is in the form of ginans (a kind of devotional hymn).[14][15]

Sindhi was the first Indo-Aryan language to be in close contact with Arabic and Persian following the Umayyad conquest of Sindh in 712 CE. According to Sindhi tradition, the first translation of the Quran into Sindhi was initiated in 883 CE in Mansura, Sindh. This is corroborated by the accounts of Al-Ramhormuzi but it is unclear whether the language of translation was actually a predecessor to Sindhi, nor is the text preserved.[16]

Medieval Sindhi (16th–19th centuries)

Medieval Sindhi religious literature comprises a syncretic Sufi and Advaita Vedanta poetry, the latter in the devotional bhakti tradition. The earliest known Sindhi poet of the Sufi tradition is Qazi Qadan (1493–1551). Other early poets were Shah Inat Rizvi (c. 1613–1701) and Shah Abdul Karim Bulri (1538–1623). These poets had a mystical bent that profoundly influenced Sindhi poetry for much of this period.[14]

Another famous part of Medieval Sindhi literature is a wealth of folktales, adapted and readapted into verse by many bards at various times. These include romantic epics such as Sassui Punnhun, Sohni Mahiwal, Momal Rano, Noori Jam Tamachi, Lilan Chanesar, and others.[17] The greatest poet of Sindhi was Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (1689/1690–1752), whose verses were compiled into the Shah Jo Risalo, published in the West by linguist Ernest Trumpp in 1866. He weaved the old folktales with Sufi mysticism.

The first attested Sindhi translation of the Quran was done by Akhund Azaz Allah Muttalawi (1747–1824 CE) and published in Gujarat in 1870. The first to appear in print was by Muhammad Siddiq in 1867.[18]

Modern Sindhi (1843–present)

Sindh was occupied by the British army and was annexed with the Bombay Presidency in 1843. Soon after, in 1848 Governor George Clerk established Sindhi as the official language in the province, removing the literary dominance of Persian. Sir Bartle Frere, the then commissioner of Sindh, issued orders on August 29, 1857 advising civil servants in Sindh to pass an examination in Sindhi. He also ordered Sindhi.[19] In 1868, the Bombay Presidency assigned Narayan Jagannath Vaidya to replace the Abjad used in Sindhi with the Khudabadi script. The script was decreed a standard script by the Bombay Presidency thus inciting anarchy in the Muslim majority region. A powerful unrest followed, after which Twelve Martial Laws were imposed by the British authorities.[20] The granting of official status of Sindhi along with script reforms ushered in the development of modern Sindhi literature.

The first printed works in Sindhi were produced at the Muhammadi Press in Bombay beginning in 1867. These included Islamic stories set in verse by Muhammad Hashim Thattvi, one of the renowned religious scholars of Sindh.[17]

The Partition of India in 1947 resulted in most Sindhi speakers ending up in the new state of Pakistan, commencing a push to establish a strong sub-national linguistic identity for Sindhi. This manifested in resistance to the imposition of Urdu and eventually Sindhi nationalism in the 1980s.[21]

The language and literary style of contemporary Sindhi writings in Pakistan and India were noticeably diverging by the late 20th century; authors from the former country were borrowing extensively from Urdu, while those from the latter were highly influenced by Hindi.[12]

Status and use

Prior to the inception of Pakistan, Sindhi was the national language of Sindh.[22][23][24][25] The Pakistan Sindh Assembly has ordered compulsory teaching of the Sindhi language in all private schools of Sindh.[26] According to the Sindh Private Educational Institutions Form B (Regulations and Control) 2005 Rules, "All educational institutions are required to teach children the Sindhi language.[27] Sindh Education and Literacy Minister, Syed Sardar Ali Shah and Secretary of School Education, Qazi Shahid Pervaiz has ordered the employment of Sindhi teachers in all private schools in Sindh so that this language can be easily and widely taught.[28] Sindhi is taught in all provincial private schools that follow the Matric system and not the ones that follow the Cambridge system.[29]

The Indian Government has legislated Sindhi as a scheduled language of India, making it an option for education. Despite lacking any state-level status, Sindhi is still a prominent minority language in the Indian state of Rajasthan.[30]

There are many Sindhi language television channels broadcasting in Pakistan such as Time News, KTN, Sindh TV, Awaz Television Network, Mehran TV and Dharti TV. Besides this, the Indian television network Doordarshan has been asked by the Indian High Court to start a news channel for Sindhi speakers in India.[31][32]

Major

Sindhi has many dialects, and forms a dialect continuum at some places with neighbouring languages such as Saraiki and Gujarati. Two major dialects are:[33][34][35][36]

- Vicholi: The prestige dialect spoken around Hyderabad and central Sindh (the Vicolo region). The literary standard of Sindhi is based on this dialect.

- Lari: The dialect of southern Sindh (Lāṛu) spoken around areas like Karachi and Sujawal.

| Dialect | Sindhi Sentence | English Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| Vicholi | Awhan kiyan ahyo? | How are you? |

| Lari | Tawhan kiyan ahyo? | How are you? |

Minor

- Siroli or Siraiki: The dialect of northern Sindh (Siro), largely similar to Vicholi.[37] Despite the name, it is distinct from the Saraiki language of South Punjab[38] and has variously been treated either as a dialect of it, or as a dialect of Sindhi.[39]

- Lasi: The dialect of Lasbela District in Balochistan, closely related to Lari and Vicholi, and in contact with Balochi.

Some scholars also classify Kutchi and Dhatki (or Thareli) as dialects of Sindhi in extent.[36]

Phonology

Sindhi has a relatively large inventory of both consonants and vowels compared to other languages. Sindhi has 46 consonant phonemes and 16 vowels. The consonant to vowel ratio is around average for the world's languages at 2.8.[40] All plosives, affricates, nasals, the retroflex flap and the lateral approximant /l/ have aspirated or breathy voiced counterparts. The language also features four implosives.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ alveolar |

Retroflex | (Alveolo-) Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m م mʱ مھ |

n ن nʱ نھ |

ɳ ڻ ɳʱ ڻھ |

ɲ ڃ |

ŋ ڱ |

|||||||

| Stop/ Affricate |

p پ pʰ ڦ | b ب bʱ ڀ |

t̪ ت tʰ ٿ | d̪ د dʱ ڌ |

ʈ ٽ ʈʰ ٺ | ɖ ڊ ɖʱ ڍ |

tɕ چ tɕʰ ڇ | dʑ ج dʑʱ جھ |

k ڪ kʰ ک | ɡ گ ɡʱ گھ |

||

| Implosive | ɓ ٻ | ɗ ڏ | ʄ ڄ | ɠ ڳ | ||||||||

| Fricative | f ف | s س | z ز | ʂ ش | x خ | ɣ غ | h ھ | |||||

| Approximant | ʋ و |

l ل lʱ لھ |

j ي |

|||||||||

| Rhotic | r ر |

ɽ ڙ ɽʱ ڙھ |

||||||||||

The retroflex consonants are apical postalveolar and do not involve curling back of the tip of the tongue,[42] so they could be transcribed [t̠, t̠ʰ, d̠, d̠ʱ n̠ n̠ʱ ɾ̠ ɾ̠ʱ] in phonetic transcription. The affricates /tɕ, tɕʰ, dʑ, dʑʱ/ are laminal post-alveolars with a relatively short release. It is not clear if /ɲ/ is similar, or truly palatal.[43] /ʋ/ is realized as labiovelar [w] or labiodental [ʋ] in free variation, but is not common, except before a stop.

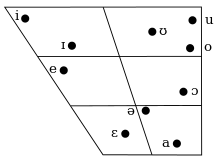

Vowels

The vowels are modal length /i e æ ɑ ɔ o u/ and short /ɪ ʊ ə/. Consonants following short vowels are lengthened: /pət̪o/ [pət̪ˑoː] 'leaf' vs. /pɑt̪o/ [pɑːt̪oː] 'worn'.

Vocabulary

According to historian Nabi Bux Baloch, most Sindhi vocabulary is from ancient Sanskrit. However, owing to the influence of the Persian language over the subcontinent, Sindhi has adapted many words from Persian and Arabic. It has also borrowed from English and Hindustani. Today, Sindhi in Pakistan is slightly influenced by Urdu, with more borrowed Perso-Arabic elements, while Sindhi in India is influenced by Hindi, with more borrowed tatsam Sanskrit elements.[44][45]

Writing systems

Sindhis in Pakistan use a version of the Perso-Arabic script with new letters adapted to Sindhi phonology, while in India a greater variety of scripts are in use, including Devanagari, Khudabadi, Khojki and Gurmukhi.[46] Perso-Arabic for Sindhi was also made digitally accessible relatively earlier.[47]

The earliest attested records in Sindhi are from the 15th century.[12] Before the standardisation of Sindhi orthography, numerous forms of Devanagari and Laṇḍā scripts were used for trading. For literary and religious purposes, a Perso-Arabic script developed by Abul-Hasan as-Sindi and Gurmukhi (a subset of Laṇḍā) were used. Another two scripts, Khudabadi and Shikarpuri, were reforms of the Landa script.[48][49] During British rule in the late 19th century, the Perso-Arabic script was decreed standard over Devanagari.[50]

Laṇḍā scripts

Laṇḍā-based scripts, such as Gurmukhi, Khojki and the Khudabadi script were used historically to write Sindhi.

Khudabadi

| Khudabadi or Sindhi | |

|---|---|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Sind (318), Khudawadi, Sindhi |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Khudawadi |

Unicode range | U+112B0–U+112FF |

The Khudabadi alphabet was invented in 1550 CE, and was used alongside other scripts by the Hindu community until the colonial era, where the sole usage of the Arabic script for official purposes was legislated.

The script continued to be used in a smaller scale by the trader community until the Partition of India in 1947.[51]

| ə | a | ɪ | i | ʊ | uː | e | ɛ | o | ɔ |

| k | kʰ | ɡ | ɠ | ɡʱ | ŋ | ||||

| c | cʰ | ɟ | ʄ | ɟʱ | ɲ | ||||

| ʈ | ʈʰ | ɖ | ɗ | ɽ | ṛ | ɳ | |||

| t | tʰ | d | dʱ | n | |||||

| p | pʰ | f | b | ɓ | bʱ | m | |||

| j | r | l | ʋ | ||||||

| ʂ | s | h | |||||||

Khojki

Khojki was employed primarily to record Muslim Shia Ismaili religious literature, as well as literature for a few secret Shia Muslim sects.[52][53]

Perso-Arabic script

| Sindhi alphabet |

|---|

| ا ب ٻ ڀ پ ت ٿ ٽ ٺ ث ج ڄ جهہ ڃ چ ڇ ح خ د ڌ ڏ ڊ ڍ ذ ر ڙ ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ڦ ق ڪ ک گ ڳ گهہ ڱ ل م ن ڻ و ھ ء ي |

|

Extended Perso-Arabic script |

|

During British rule in India, a variant of the Persian alphabet was adopted for Sindhi in the 19th century. The script is used in Pakistan and India today. It has a total of 52 letters, augmenting the Persian with digraphs and eighteen new letters (ڄ ٺ ٽ ٿ ڀ ٻ ڙ ڍ ڊ ڏ ڌ ڇ ڃ ڦ ڻ ڱ ڳ ڪ) for sounds particular to Sindhi and other Indo-Aryan languages. Some letters that are distinguished in Arabic or Persian are homophones in Sindhi.

| جهہ | ڄ | ج | پ | ث | ٺ | ٽ | ٿ | ت | ڀ | ٻ | ب | ا |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ɟʱ | ʄ | ɟ | p | s | ʈʰ | ʈ | tʰ | t | bʱ | ɓ | b | ɑː ʔ ∅ |

| ڙ | ر | ذ | ڍ | ڊ | ڏ | ڌ | د | خ | ح | ڇ | چ | ڃ |

| ɽ | r | z | ɖʱ | ɖ | ɗ | dʱ | d | x | h | cʰ | c | ɲ |

| ڪ | ق | ڦ | ف | غ | ع | ظ | ط | ض | ص | ش | س | ز |

| k | q | pʰ | f | ɣ | ɑː oː eː ʔ ∅ | z | t | z | s | ʂ | s | z |

| ي | ء | ھ | و | ڻ | ن | م | ل | ڱ | گهہ | ڳ | گ | ک |

| j iː | ʔ ∅ | h | ʋ ʊ oː ɔː uː | ɳ | n | m | l | ŋ | ɡʱ | ɠ | ɡ | kʰ |

Devanagari script

In India, the Devanagari script is also used to write Sindhi.[52] A modern version was introduced by the government of India in 1748; however, it did not gain full acceptance, so both the Sindhi-Arabic and Devanagari scripts are used. In India, a person may write a Sindhi language paper for a Civil Services Examination in either script.[54] Diacritical bars below the letter are used to mark implosive consonants, and dots called nukta are used to form other additional consonants.

| अ | आ | इ | ई | उ | ऊ | ए | ऐ | ओ | औ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ə | a | ɪ | i | ʊ | uː | e | ɛ | o | ɔ |

| क | ख | ख़ | ग | ॻ | ग़ | घ | ङ | ||

| k | kʰ | x | ɡ | ɠ | ɣ | ɡʱ | ŋ | ||

| च | छ | ज | ॼ | ज़ | झ | ञ | |||

| c | cʰ | ɟ | ʄ | z | ɟʱ | ɲ | |||

| ट | ठ | ड | ॾ | ड़ | ढ | ढ़ | ण | ||

| ʈ | ʈʰ | ɖ | ɗ | ɽ | ɖʱ | ɽʱ | ɳ | ||

| त | थ | द | ध | न | |||||

| t | tʰ | d | dʱ | n | |||||

| प | फ | फ़ | ब | ॿ | भ | म | |||

| p | pʰ | f | b | ɓ | bʱ | m | |||

| य | र | ल | व | ||||||

| j | r | l | ʋ | ||||||

| श | ष | स | ह | ||||||

| ʂ | ʂ | s | h | ||||||

Gujarati script

The Gujarati script is used to write the Kutchi Language in India.[55]

See also

- 1972 Sindhi Language Bill

- Institute of Sindhology

- Sindhi Transliteration

- Languages of India

- Languages of Pakistan

- Languages with official status in India

- List of Sindhi-language films

- Provincial languages of Pakistan

- Sindhi literature

- Sindhi poetry

Notes

- It is one of 22 Eighth Schedule languages for which the Constitution mandates development.

- This is the number of people who identified their language as "Sindhi"; it does not include speakers of related languages, like Kutchi.

References

- 30.26 million in Pakistan (2017 census), 1.68 million in India (2011 census).

- Majeed, Gulshan. "Ethnicity and Ethnic Conflict in Pakistan" (PDF). Journal of Political Studies. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- "Sindhi". The Languages Gulper. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica". Sindhi Language. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- "Languages Included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constution". Department of Official Language, Ministry of Home Affairs. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- "Sindhi Language, Sindhi Dialects, Sindhi Vocabulary, Sindhi Literature, Sindhi, Language, History of Sindhi language". Indian Mirro. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- "CCI defers approval of census results until elections". Dawn. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2021. The figure of 30.26 million is calculated from the reported 14.57% for the speakers of Sindhi and the 207.685 million total population of Pakistan.

- "2011 Census tables: C-16, population by mother tongue". Census of India Website. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "Sindhi". The Languages Gulper. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- Wadhwani, Y. K. (1981). "The Origin of the Sindhi Language" (PDF). Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. 40: 192–201. JSTOR 42931119. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- "Sindhi language | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- "Sindhi Language - Structure, Writing & Alphabet". Mustgo.com. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Christopher Shackle, Sindhi literature at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Sacred Literature-Ginans". Ismaili.NET. Heritage Society. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1963). "Translations and Commentaries of the Qur'ān in Sindhi Language". Oriens. 16: 224–243. doi:10.2307/1580264. JSTOR 1580264. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1971). "Sindhi Literature". Mahfil. 7 (1/2): 71–80. JSTOR 40874414.

- "The Holy Qur'an and its Translators – Imam Reza (A.S.) Network". Imamreza.net. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Memon, Naseer (April 13, 2014). "The language link". The News on Sunday. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- "Sindhi alphabets, pronunciation and language". Omniglot. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- Levesque, Julien (2021). "Beyond Success or Failure: Sindhi Nationalism and the Social Construction of the "Idea of Sindh"". Journal of Sindhi Studies. 1 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1163/26670925-bja10001. S2CID 246560343. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- Language and Politics in Pakistan. "The Sindhi Language Movement". academia.edu. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "The Imposition Of Urdu". NAWAIWAQT GROUP OF NEWSPAPERS. September 10, 2015. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "Microsoft Word - Teaching of Sindhi & Sindhi ethnicity.doc" (PDF). Apnaorg.com. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- "The Sindhi Language Movement" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-05. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- Samar, Azeem (13 March 2019). "PA resolution calls for teaching Sindhi as compulsory subject in private schools". The News International. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- PakistanToday (25 September 2018). "Sindhi to be made compulsory in all private schools across province | Pakistan Today". Pakistan Today. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- "Private schools directed to make Sindhi compulsory subject". Dawn. 2018-09-25. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- "Sindh private schools told to teach Sindhi as compulsory subject". Samaa TV. 2018-09-24. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- "National Committee for Linguistic Minorities" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-13. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- "24hr news channel for Sindhis: HC seeks Centre's response". Business Standard Private Ltd. Press Trust of India. September 4, 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "Sindhi". Accredited Language Services. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Sindhi language at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- Austin, Peter; Austin, Marit Rausing Chair in Field Linguistics Peter K. (2008). One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520255609.

- Paniker, K. Ayyappa (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 9788126003655.

- Grierson, George A. (1919). "Sindhi". Linguistic Survey of India. Vol. VIII North-western group. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India.

- Shackle 2007, p. 114.

- Masica, Colin P. (1991). The Indo-Aryan languages. Cambridge language surveys. Cambridge University Press. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-521-23420-7.

- Rahman, Tariq (1995). "The Siraiki Movement in Pakistan". Language Problems & Language Planning. 19 (1): 3. doi:10.1075/lplp.19.1.01rah.

- Nihalani, Paroo. (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (Sindhi). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nihalani, Paroo (December 1, 1995). "Illustration of the IPA – Sindhi". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 25 (2): 95–98. doi:10.1017/S0025100300005235. S2CID 249410954.

- Nihalani 1974, p. 207.

- The IPA Handbook uses the symbols c, cʰ, ɟ, ɟʱ, but makes it clear this is simply tradition and that these are neither palatal nor stops, but "laminal post-alveolars with a relatively short release". Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:83) confirm a transcription of [t̠ɕ, t̠ɕʰ, d̠ʑ, d̠ʑʱ] and further remarks that "/ʄ/ is often a slightly creaky voiced palatal approximant" (caption of table 3.19).

- Cole (2001:652–653)

- Khubchandani (2003:624–625)

- Nair, Manoj R. (2018-07-30). "The dispute over script still endures among Sindhis". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- "Sindhi becomes the first language from Pakistan to be selected for digitization". Geo News. Dec 7, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Khubchandani (2003:633)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Cole (2001:648)

- "Sindhi Language: Script". Sindhilanguage.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "Proposal to Encode the Sindhi Script in ISO/IEC 10646" (PDF). Std.dkuug.dk. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "Final Proposal to Encode the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646" (PDF). Std.dkuug.dk. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-22. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Gujarati alphabet, pronunciation and language". Omniglot. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

- "Romanized Sindhi is teaching reading speaking writing sindhi language globally under alliance of sindhi association of Americas Inc". Romanizedsindhi.org. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "CHOICE OF SCRIPT FOR OUR SINDHI LANGUAGE". Chandiramani.com. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

Sources

- Nihalani, Paroo (1974). "Lingual Articulation of Stops in Sindhi". Phonetica. 30 (4): 197–212. doi:10.1159/000259489. ISSN 1423-0321. PMID 4424983. S2CID 3325314.

- Addleton and Brown (2010). Sindhi: An Introductory Course for English Speakers. South Hadley: Doorlight Publications. Archived from the original on 2010-08-28. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- Bughio, M. Qasim (January–June 2006). Maniscalco, Fabio Maniscalco (ed.). "The Diachronic Sociolinguistic Situation in Sindh". Web Journal on Cultural Patrimony. 1.

- Cole, Jennifer S (2001). "Sindhi". In Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.). Facts About the World's Languages. H W Wilson. pp. 647–653. ISBN 0-8242-0970-2.

- International Phonetic Association. 1999. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- Khubchandani, Lachman M (2003). "Sindhi". In Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 622–658. ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4.

- Shackle, Christopher (2007). "Pakistan". In Simpson, Andrew (ed.). Language and national identity in Asia. Oxford linguistics Y. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922648-1.

- Trumpp, Ernest (1872). Grammar of the Sindhi Language. London: Trübner and Co. ISBN 81-206-0100-9.

- Chopra, R. M (2013). "Persian in Sindh". The rise, growth, and decline of Indo-Persian literature (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Iran Culture House. OCLC 909254259.

External links

- Sindhi Language Authority

- Sindhi Dictionary

- All about Sindhi language and culture at the Wayback Machine (archived August 31, 2015)

- Mewaram's 1910 Sindhi-English dictionary