Australian dollar

The Australian dollar (sign: $; code: AUD) is the currency of Australia, including its external territories: Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and Norfolk Island. It is officially used as currency by three independent Pacific Island states: Kiribati, Nauru, and Tuvalu. It is legal tender in Australia.[1] Within Australia, it is almost always abbreviated with the dollar sign ($), with A$ or AU$ sometimes used to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies.[2][3] The $ symbol precedes the amount. It is subdivided into 100 cents.

| Australian dollar | |

|---|---|

A$, AU$ | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | AUD |

| Number | 036 |

| Subunit decimals | 2 |

| Unit | |

| Unit | dollar |

| Symbol | $ |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | cent |

| Symbol | |

| cent | c |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | $5, $10, $20, $50, $100 |

| Rarely used | $1, $2 (no longer in production) |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | 5c, 10c, 20c, 50c, $1, $2 |

| Rarely used | 1c, 2c (no longer in production) |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 14 February 1966 |

| Replaced | Australian pound |

| User(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| Website | www |

| Printer | Note Printing Australia |

| Website | www |

| Mint | Royal Australian Mint |

| Website | www |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 6.1% (Australia only) |

| Source | Reserve Bank of Australia, June 2022. |

| Pegged by | Tuvaluan dollar and Kiribati dollar at par |

The Australian dollar was introduced on 14 February 1966 to replace the pre-decimal Australian pound, with the conversion rate of two dollars to the pound.

In 2016, the Australian dollar was the fifth-most-traded currency in world foreign exchange markets, accounting for 6.9% of the world's daily share. In the same year, there were A$71.12 billion in Australian currency in circulation, or A$2,932 per person in Australia,[4] which includes cash reserves held by the banking system and cash in circulation in other countries or held as a foreign exchange reserve.

Constitutional basis

Section 51(xii) of the Constitution of Australia gives the Commonwealth (federal) Parliament the power to legislate with respect to "currency, coinage, and legal tender".

The currency power must be read in conjunction with other parts of the Australian Constitution. Section 115 of the Constitution provides: "A State shall not coin money, nor make anything but gold and silver coin a legal tender in payment of debts."[5]

Under this provision the Perth Mint, owned by the Western Australian government, still produces gold and silver coins with legal tender status, the Australian Gold Nugget and Australian Silver Kookaburra. These, however, although having the status of legal tender, are almost never circulated or used in payment of debts, and are mostly considered bullion coins. Australian coins are now produced at the Royal Australian Mint in Canberra.

History

Early moves towards decimalisation

Before the adoption of the current Australian dollar in 1966, Australia's currency was the Australian pound, which like the British pound sterling was divided into 20 shillings and each shilling was divided into 12 pence, making a pound worth 240 pence. The Australian pound was introduced in 1910 at par with the pound sterling or A£1 = UK£1 until 1931, when it was devalued to A£1 = UK£0.8 or 16 shillings UK.[6]

In 1902, a select committee of the House of Representatives, chaired by George Edwards, had recommended that Australia adopt a decimal currency with the pound divided into ten florins and the florin into 100 cents.[7] In 1937, the Banking Royal Commission[note 1] appointed by the Lyons Government had recommended that Australia adopt "a system of decimal coinage … based upon the division of the Australian pound into 1000 parts".[8]

Adoption of the dollar

In February 1959, Treasurer Harold Holt appointed a Decimal Currency Committee, chaired by Walter D. Scott, to examine the merits of decimalisation. The committee reported in August 1960 in favour of decimalisation and recommended that a new currency be introduced in February 1963, with the adoption to be modelled on South Africa's replacement of the South African pound with the rand worth 10 shillings or 1⁄2 pound. The Menzies Government announced its support for decimalisation in July 1961, but delayed the process in order to give further consideration to the implementation process.[9] In April 1963, Holt announced that a decimal currency was scheduled to be introduced in February 1966, with a base unit equal to 10 shillings, and that a Decimal Currency Board would be established to oversee the transition process.[8]

A public consultation process was held in which over 1,000 names were suggested for the new currency. In June 1963, Holt announced that the new currency would be called the "royal". This met with widespread public disapproval, and three months later it was announced that it would instead be named the "dollar".[10]

The Australian pound was replaced by the Australian dollar on 14 February 1966[11] with the conversion rate of A$2 = A£1. Since Australia was still part of the fixed-exchange sterling area, the exchange rate was fixed to the pound sterling at a rate of A$1 = 8 U.K. shillings (or UK£1 = A$2.50, and in turn UK£1 = US$2.80). In 1967, Australia effectively left the sterling area when the pound sterling was devalued against the US dollar from US$2.80 to US$2.40, but the Australian dollar chose to retain its peg to the US dollar at A$1 = US$1.12 (hence appreciating in value versus sterling).

The Australian dollar is legal tender in its external territories: Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and Norfolk Island; and is also official currency in Kiribati, Nauru, and Tuvalu. It was legal tender in Papua New Guinea until 31 December 1975 when it was replaced by the Papua New Guinean kina, and in Solomon Islands until 1977 when it was replaced by the Solomon Islands dollar.

Coins

In 1966, coins were introduced in denominations of 1 and 2 cents (bronze); 5, 10, and 20 cents (cupronickel; 75% copper, 25% nickel); and 50 cents (silver, then cupronickel). The 50-cent coins in 80% silver were withdrawn after a year when the intrinsic value of the silver content was found to considerably exceed the face value of the coins. Aluminium bronze (92% copper, 6% aluminium, 2% nickel) 1-dollar coins were introduced in 1984, followed by aluminium bronze 2-dollar coins in 1988, to replace the banknotes of that value. 1- and 2-cent coins were discontinued in 1991 and withdrawn from circulation in 1992; since then cash transactions have been rounded to the nearest 5 cents.

| Value | Image | Technical parameters | Description | Date of first minting | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | Reverse | Diameter | Thickness | Weight | Composition | Edge | Obverse | Reverse | ||

| 1c | 17.65 mm | >1.4 mm | 2.60 g | 97% copper 2.5% zinc 0.5% tin |

Plain | Queen Elizabeth II | Feathertail glider | 1966-1991 (no longer issued) | ||

| 2c | 21.59 mm | <1.9 mm | 5.20 g | Frill-necked lizard | ||||||

| 5c | 19.41 mm | 1.3 mm | 2.83 g | Cupronickel 75% copper 25% nickel |

Reeded | Queen Elizabeth II |

Echidna | 1966 | ||

| 10c | 23.60 mm | 2.0 mm | 5.65 g | Superb lyrebird | ||||||

| 20c | 28.65 mm | 2.5 mm | 11.3 g | Platypus | ||||||

| 50c | 31.65 mm (across flats) | 2.5 mm | 15.55 g | Plain | Coat of arms | 1969 | ||||

| $1 | 25.00 mm | 2.8 mm | 9.00 g | 92% copper 6% aluminium 2% nickel |

Interrupted milled |

Queen Elizabeth II |

Five kangaroos | 1984 | ||

| $2 | 20.50 mm | 3.0 mm | 6.60 g | Aboriginal elder and Southern Cross | 1988 | |||||

Australia's coins are produced by the Royal Australian Mint, which is located in the nation's capital, Canberra. Since opening in 1965, the Mint has produced more than 14 billion circulating coins, and has the capacity to produce more than two million coins per day, or more than 600 million coins per year.

Current Australian 5-, 10- and 20-cent coins are identical in size to the former Australian, New Zealand, and British sixpence, shilling, and two shilling (florin) coins. Pre-decimal Australian coins remain legal tender for 10 cents per shilling. Before 2006 the old New Zealand 5-, 10- and 20-cent coins were often mistaken for Australian coins of the same value, and vice versa, and therefore circulated in both countries. The UK replaced these coins with smaller versions from 1990 to 1993, as did New Zealand in 2006. Still, some confusion occurs with the larger-denomination coins in the two countries; Australia's $1 coin is similar in size to New Zealand's $2 coin, and the New Zealand $1 coin is similar in size to Australia's $2 coin.

With a mass of 15.55 grams (0.549 oz) and a diameter of 31.51 millimetres (1+1⁄4 in), the Australian 50-cent coin is one of the largest coins used in the world today.

Commemorative coins

The Royal Australian Mint also has an international reputation for producing quality numismatic coins. It has first issued commemorative 50-cent coins in 1970, commemorating James Cook's exploration along the east coast of the Australian continent, followed in 1977 by a coin for Queen Elizabeth II's Silver Jubilee, the wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981, the Brisbane Commonwealth Games in 1982, and the Australian Bicentenary in 1988. Issues expanded into greater numbers in the 1990s and the 21st century, responding to collector demand. Commemorative designs have also been featured on the circulating two dollar, one dollar, and 20 cent coins.

In commemoration of the 40th anniversary of decimal currency, the 2006 mint proof and uncirculated sets included one- and two-cent coins. In early 2013, Australia's first triangular coin was introduced to mark the 25th anniversary of the opening of Parliament House. The silver $5 coin is 99.9% silver, and depicts Parliament House as viewed from one of its courtyards.[13]

Banknotes

First series

The first paper issues of the Australian dollar were issued in 1966. The $1, $2, $10 and $20 notes had exact equivalents in the former pound notes. The $5 note was issued in 1967, the $50 was issued in 1973 and the $100 was issued in 1984.[14]

The $1 banknote was replaced by a $1 coin in 1984, while the $2 banknote was replaced by a smaller $2 coin in 1988.[15] Although no longer printed, all previous notes of the Australian dollar are still considered legal tender.[16]

Shortly after the changeover, substantial counterfeiting of $10 notes was detected. This provided an impetus for the Reserve Bank of Australia to develop new note technologies jointly with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, culminating in the introduction of the first polymer banknote in 1988.

First polymer series

Australia was the first country to produce polymer banknotes,[17] more specifically made of polypropylene polymer, which were produced by Note Printing Australia. These revolutionary polymer notes are cleaner than paper notes, are more durable and easily recyclable.

The first polymer banknote was issued in 1988 as a $10 note[18] commemorating the bicentenary of European settlement in Australia. The note depicted on one side a young male Aboriginal person in body paint, with other elements of Aboriginal culture. On the reverse side was the ship Supply from the First Fleet, with a background of Sydney Cove, as well as a group of people to illustrate the diverse backgrounds from which Australia has evolved over 200 years.

The first polymer series was rolled out starting 1992 and featured the following persons:

- The $100 note features world-renowned soprano Dame Nellie Melba (1861–1931), and the distinguished soldier, engineer and administrator General Sir John Monash (1865–1931).[19]

- The $50 note features Aboriginal writer and inventor David Unaipon (1872–1967), and Australia's first female parliamentarian, Edith Cowan (1861–1932).[20]

- The $20 note features the founder of the world's first aerial medical service (the Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia), the Reverend John Flynn (1880–1951), and Mary Reibey (1777–1855), who arrived in Australia as a convict in 1792 and went on to become a successful shipping magnate and philanthropist.[21]

- The $10 note features the poets AB "Banjo" Paterson (1864–1941) and Dame Mary Gilmore (1865–1962). This note incorporates micro-printed excerpts of Paterson's and Gilmore's work.[22]

- The $5 note features Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and Parliament House, Canberra, the national capital.[23]

A special centenary issue of the $5 note featured Sir Henry Parkes and Catherine Helen Spence in 2001. In 2015–2016 there were petitions to feature Fred Hollows on the upgraded $5 note, but failed to push through when the new note was introduced on 1 September 2016.[24][25][26]

Australia also prints polymer banknotes for a number of other countries through Note Printing Australia, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Reserve Bank of Australia. Note Printing Australia prints polymer notes or simply supplies the polymer substrate[27] for a growing number of other countries including Bangladesh, Brunei, Chile, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Nepal, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Romania, Samoa, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. Many other countries are showing a strong interest in the new technology.

Second polymer series

On 27 September 2012, the Reserve Bank of Australia stated that it had ordered work on a project to upgrade the current banknotes. The upgraded banknotes would incorporate a number of new future proof security features [28] and include tactile features like Braille dots for ease of use of the visually impaired. [29][30] All persons featured on the first polymer series were retained on the second polymer series.

| Note | Obverse | Reverse | Dimensions (mm) | Main colour | Embossing | Issued | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $5 | Queen Elizabeth II | Parliament House | 130 × 65 | Violet, purple | Federation star | 1 September 2016[26] | |||||

| $10 | Banjo Paterson | Dame Mary Gilmore | 137 × 65 | Blue | Pen nib | 20 September 2017[33] | |||||

| $20 | Mary Reibey | Reverend John Flynn | 144 × 65 | Red/Orange | Compass | 9 October 2019[34] | |||||

| $50 | David Unaipon | Edith Cowan | 151 × 65 | Yellow | Book | 18 October 2018[35] | |||||

| $100 | Dame Nellie Melba | Sir John Monash | 158 × 65 | Green | Fan | 29 October 2020[36][37] | |||||

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre. For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | |||||||||||

Exchange rates

Exchange rate history

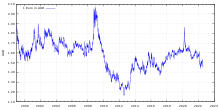

Prior to 1983, Australia maintained a fixed exchange rate. The Australian pound was initially at par from 1910 with the British pound or A£1 = UK£1; from 1931 it was devalued to A£1 = UK£0.8 or 16 shillings sterling. This reflected its historical ties as well as a view about the stability in value of the British pound.

From 1946 to 1971, Australia maintained a peg under the Bretton Woods system, a fixed exchange rate system that pegged the U.S. dollar to gold, but the Australian dollar was effectively pegged to sterling until 1967 at UK£1 = A£1.25 = A$2.50 = US$2.80. In 1967 Australia did not follow the pound sterling devaluation and remained fixed to the U.S. dollar at A$1 = US$1.12.

With the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, Australia converted the traditional peg to a fluctuating rate against the US dollar. In September 1974, Australia valued the dollar against a basket of currencies called the trade weighted index (TWI) in an effort to reduce the fluctuations associated with its tie to the US dollar.[38] The daily TWI valuation was changed in November 1976 to a periodically adjusted valuation.

The highest valuation of the Australian dollar relative to the U.S. dollar was during the period of the peg to the U.S. dollar. On 9 September 1973, the peg was adjusted to US$1.4875, the fluctuation limits being changed to US$1.485–US$1.490;[39] on both 7 December 1973 and 10 December 1973, the noon buying rate in New York City for cable transfers payable in foreign currencies reached its highest point of 1.4885 U.S. dollars to one dollar.[40]

In December 1983, the Australian Labor government led by Prime Minister Bob Hawke and Treasurer Paul Keating floated the dollar, with the exchange rate reflecting the balance of payments as well as supply and demand on international money markets. The decision was made on 8 December 1983 and announced on 9 December 1983.[41]

In the two decades that followed, its highest value relative to the US dollar was $0.881 in December 1988. The lowest ever value of the dollar after it was floated was 47.75 US cents in April 2001.[42] It returned to above 96 US cents in June 2008,[43] and reached 98.49 later that year. Although the value of the dollar fell significantly from this high towards the end of 2008, it gradually recovered in 2009 to 94 US cents.

On 15 October 2010, the dollar reached parity with the US dollar for the first time since becoming a freely traded currency, trading above US$1 for a few seconds.[44] The currency then traded above parity for a sustained period of several days in November, and fluctuated around that mark into 2011.[45] On 27 July 2011, the dollar hit a record high since floating, at $1.1080 against the US dollar.[46] Some commentators speculated that its high value that year was related to Europe's sovereign debt crisis, and Australia's strong ties with material importers in Asia and in particular China.[47]

Since the end of the China's large-scale purchases of Australian commodities in 2013, however, the Australian dollar's value versus the US dollar has since plunged to $0.88 as of end-2013, and to as low as $0.57 in March 2020. As of 2021, it has traded at a range of $0.71 to $0.80.

Determinants of value

In 2016, the Australian dollar was the fifth most traded currency in world foreign exchange markets, accounting for 6.9% of the world's daily share (down from 8.6% in 2013)[48] behind the United States dollar, the euro, the Japanese yen and the pound sterling.

The Australian dollar is popular with currency traders, because of the comparatively high interest rates in Australia, the relative freedom of the foreign exchange market from government intervention, the general stability of Australia's economy and political system, and the prevailing view that the Australian dollar offers diversification benefits in a portfolio containing the major world currencies, especially because of its greater exposure to Asian economies and the commodities cycle.[49]

Economists posit that commodity prices are the dominant driver of the Australian dollar, and this means changes in exchange rates of the Australian dollar occur in ways opposite to many other currencies.[50] For decades, Australia's balance of trade has depended primarily upon commodity exports such as minerals and agricultural products. This means the Australian dollar varies significantly during the business cycle, rallying during global booms as Australia exports raw materials, and falling during recessions as mineral prices slump or when domestic spending overshadows the export earnings outlook. This movement is in the opposite direction to other reserve currencies, which tend to be stronger during market slumps as traders move value from falling stocks into cash.

The Australian dollar is a reserve currency and one of the most traded currencies in the world.[49] Other factors in its popularity include a relative lack of central bank intervention, and general stability of the Australian economy and government.[51] In January 2011 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Alexey Ulyukaev announced that the Central Bank of Russia would begin keeping Australian dollar reserves.[52]

| Rank | Currency | ISO 4217 code |

Symbol | Proportion of daily volume, April 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | USD | US$ | 88.3% | |

2 | EUR | € | 32.3% | |

3 | JPY | 円 / ¥ | 16.8% | |

4 | GBP | £ | 12.8% | |

5 | AUD | A$ | 6.8% | |

6 | CAD | C$ | 5.0% | |

7 | CHF | CHF | 5.0% | |

8 | CNY | 元 / ¥ | 4.3% | |

9 | HKD | HK$ | 3.5% | |

10 | NZD | NZ$ | 2.1% | |

11 | SEK | kr | 2.0% | |

12 | KRW | 원 / ₩ | 2.0% | |

13 | SGD | S$ | 1.8% | |

14 | NOK | kr | 1.8% | |

15 | MXN | $ | 1.7% | |

16 | INR | ₹ | 1.7% | |

17 | RUB | ₽ | 1.1% | |

18 | ZAR | R | 1.1% | |

19 | TRY | ₺ | 1.1% | |

20 | BRL | R$ | 1.1% | |

21 | TWD | NT$ | 0.9% | |

22 | DKK | kr | 0.6% | |

23 | PLN | zł | 0.6% | |

24 | THB | ฿ | 0.5% | |

25 | IDR | Rp | 0.4% | |

26 | HUF | Ft | 0.4% | |

27 | CZK | Kč | 0.4% | |

28 | ILS | ₪ | 0.3% | |

29 | CLP | CLP$ | 0.3% | |

30 | PHP | ₱ | 0.3% | |

31 | AED | د.إ | 0.2% | |

32 | COP | COL$ | 0.2% | |

33 | SAR | ﷼ | 0.2% | |

34 | MYR | RM | 0.1% | |

35 | RON | L | 0.1% | |

… | 2.2% | |||

| Total[note 2] | 200.0% | |||

Legal tender

Australian notes are legal tender throughout Australia by virtue of the Reserve Bank Act 1959, s.36(1),[1] without an amount limit. Part IV of the Currency Act 1965[54] similarly provides that Australian coins intended for general circulation are also legal tender, but only for the following amounts:

- 1c and 2c coins (withdrawn from circulation from February 1992, but still legal tender): for payments not exceeding 20¢

- 5c, 10c, 20c and 50c (of any combination): for payments not exceeding $5

- $1 coins: for payments not exceeding $10

- $2 coins: for payments not exceeding $20

- Non-circulating $10 coins: for payments not exceeding $100 [55]

- Coins of other denominations: no lower limit

Although the Reserve Bank Act 1959 and the Currency Act 1965 establishes that Australian banknotes and coins have legal tender status, Australian banknotes and coins do not necessarily have to be used in transactions and refusal to accept payment in legal tender is not unlawful. A provider of goods or services may specify the payment method before a "contract" is entered into, such as in the case of online transactions. If a provider of goods or services specifies another means of payment prior to the contract, then there is usually no obligation for legal tender to be accepted as payment. This is the case even when an existing debt is involved. However, refusal to accept legal tender in payment of an existing debt, where no other means of payment/settlement has been specified in advance, conceivably may have legal consequences.[56][57]

See also

- Banking in Australia

- Brass razoo

- Coins of Australia

- Economy of Australia

- Note Printing Australia

- Section 51 (xii) of the Constitution of Australia

Other main currencies

Notes

- In full, the "Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the monetary and banking systems at present in operation in Australia"

- The total sum is 200% because each currency trade always involves a currency pair; one currency is sold (e.g. US$) and another bought (€). Therefore each trade is counted twice, once under the sold currency ($) and once under the bought currency (€). The percentages above are the percent of trades involving that currency regardless of whether it is bought or sold, e.g. the US dollar is bought or sold in 88% of all trades, whereas the euro is bought or sold 32% of the time.

References

Citations

- Reserve Bank Act 1959, s.36(1), and Currency Act 1965, s.16.

- McGovern, Gerry; Norton, Rob; O'Dowd, Catherine (2002). The Web content style guide: an essential reference for online writers ... FT Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-273-65605-0. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- The Canadian Style. Dundurn Press/Translation Bureau. 1997. ISBN 1-55002-276-8. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (October 2017). Statistics on payment, clearing and settlement systems in the CPMI countries, Figures for 2016.

- "COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA CONSTITUTION ACT – SECT 115 States not to coin money". Austlii.edu.au. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- "Banknotes of the 1930s". Reserve Bank of Australia Museum. Reserve Bank of Australia. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "Report from the Select Committee on Coinage" (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia. 3 April 1902.

- "A New Currency". Reserve Bank of Australia Museum. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- "Report of the 1959 Decimal Currency Committee". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1959. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- "The Introduction of Decimal Currency: How We Avoided Nostrils and Learned to Love the Bill". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- "Introducing the New Decimal Banknotes". Reserve Bank of Australia Museum. Reserve Bank of Australia. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "Coin Types | Royal Australian Mint". www.ramint.gov.au. Royal Australian Mint. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Triangular coin celebrates Parliament House's birthday". ABC News. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- History of Banknotes http://banknotes.rba.gov.au/australias-banknotes/history/

- "The Reserve Bank and Reform of the Currency: 1960–1988, Inflation and the Note Issue". Reserve Bank of Australia Music um. Reserve Bank of Australia. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "DELIBERATE DAMAGE". Legal. Reserve Bank of Australia. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

All Australian banknotes, present and all past issues, are lawfully current in Australia.

- "Wi-fi, dual-flush loos and eight more Australian inventions". BBC News. 8 November 2012. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Other Banknotes". Reserve Bank of Australia Banknotes.

- "$100 Banknote". Reserve Bank of Australia Banknotes.

- "$50 Banknote". Reserve Bank of Australia Banknotes.

- "$20 Banknote". Reserve Bank of Australia Banknotes.

- "$10 Banknote". Reserve Bank of Australia Banknotes.

- "$5 Banknote". Reserve Bank of Australia Banknotes.

- "Campaign to put Fred Hollows on Australian $5 note". Stuff. 25 January 2016. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- Vernon, Jackson; Dalzell, Stephanie (25 January 2016). "'Put Fred on a fiver': Call for Australian great to feature on banknote". ABC News. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Next Generation of Banknotes: $5 Banknote Design Reveal". www.rba.gov.au. Reserve Bank of Australia. 12 April 2016. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Paying with Polymer: Developing Canada's New Bank Notes" (PDF). Bank of Canada. 20 June 2011. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Media Release: R.B.A.: Upgrading Australia's Banknotes http://www.rba.gov.au/media-releases/2012/mr-12-27.html

- "Next Generation Banknotes: Additional Feature for the Vision Impaired". www.rba.gov.au (Press release). Media Office-Reserve Bank of Australia. 13 February 2015.

- Haxton, Nance (19 February 2015). "RBA to introduce tactile banknotes after 13yo blind boy Connor McLeod campaigns for change". ABC News. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- "A Complete Series of Polymer Banknotes: 1992–1996". Reserve Bank of Australia Museum. Reserve Bank of Australia. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "RBA Banknotes: Banknote Features". Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- "Next Generation of Banknotes: $10 Design Reveal". www.rba.gov.au. Reserve Bank of Australia. 17 February 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Next Generation of Banknotes: $20 Enters General Circulation". www.rba.gov.au. Reserve Bank of Australia. 8 October 2019. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Next Generation of Banknotes: Circulation Date for the New $50 Banknote". www.rgba.gov.au. Reserve Bank of Australia. 5 September 2018. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018.

- "Next Generation of Banknotes: Circulation Date for the New Banknote". www.rba.gov.au. Reserve Bank of Australia. 30 September 2020. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Australia's new $100 banknote enters circulation". 9 News Australia. 29 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "1350.0 – Australian Economic Indicators, Mar 1998". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 8 December 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Cowitt, Philip P., ed. (1985). World Currency Yearbook, 1984. International Currency Analysis. p. 75. ISBN 0-917645-00-6.

- "U.S. / Australia Foreign Exchange Rate". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "20 years since Aussie dollar floated". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 December 2003. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "Global risk weighs on Howard's agenda". CNN. 12 November 2001. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "Dollar Falls Before RBA Meeting: New Zealand's Drops". Bloomberg. 30 June 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "Dollar hits parity vs US dollar". Reuters. 15 October 2010. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- Davis, Bradley (4 November 2010). "Dollar hits new post-float high after US central bank move". The Australian. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- "AUD/USD Slides After Topping 1.10 Level – Westpac". Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "Sky News: Aussie dollar hits new highs". Sky News. 28 March 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- Desjardins, Jeff (29 December 2016). "Here are the most traded currencies in 2016". Business Insider. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- Yeates, Clancy (2 September 2010). "Aussie now fifth most traded currency". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- "Westpac Market Insights March 2011" (PDF). Westpac. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- Dorsch, Gary (14 February 2006). "Analyzing the Dollar – Up, Down, and Under". SafeHaven.com.

- "Russia to Keep Dollar Reserves From February". Davos, Switzerland: RIA Novosti. 26 January 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- "Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2019" (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. 16 September 2019. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Currency Act 1965". www.legislation.gov.au. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- "Currency Act 1965".

- "RBA Banknotes: Legal Tender". rba.gov.au. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014.

- "Reserve Bank of Australia – Home Page". rba.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

Sources

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

External links

- Sound recording of 1966 Decimal Currency radio advertisement held at the National Archives of Australia

- Reserve Bank of Australia: Current Banknotes

- The Perth Mint is Australia's precious metals mint, making non-circulating/collector coins in silver, gold, and platinum.

- Note Printing Australia is the printer of Australia's notes, and also inventor of the abovementioned polymer banknotes, and world exporter of this technology.

- The Money Tracker site allows users to track Australian banknotes as they circulate around Australia.

- Images of historic and modern Australian bank notes

- Reserve Bank of Australia – daily value of AUD against 13 currencies, special drawing right and trade weighted index

- Reserve Bank of Australia – historical data of AUD since 1969 (various .xls files)

- – historical exchange rates of AUD/USD (from the year 1800 to present time).

- – historical chart of AUD/USD (from the year 1800 to present time).

- The banknotes of Australia (in English and German)

| Preceded by: Australian pound Reason: decimalisation Ratio: 2 dollars = 1 pound |

Currency of Australia, Christmas Island, Cocos Islands, Norfolk Island, Nauru, Kiribati, Tuvalu 1966 – |

Succeeded by: Current |

| Preceded by: New Guinean pound Reason: decimalisation Ratio: 2 dollars = 1 pound |

Currency of Papua New Guinea 1966 – 1975 |

Succeeded by: Papua New Guinean kina Reason: currency independence Ratio: at par |

| Preceded by: Australian pound Reason: decimalisation Ratio: 2 dollars = 1 pound |

Currency of Solomon Islands 1966 – 1977 |

Succeeded by: Solomon Islands dollar Reason: currency independence Ratio: at par |