Electoral system of Australia

The Australian electoral system comprises the laws and processes used for the election of members of the Australian Parliament and is governed primarily by the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. The system presently has a number of distinctive features including compulsory enrolment; compulsory voting; majority-preferential instant-runoff voting in single-member seats to elect the lower house, the House of Representatives; and the use of the single transferable vote proportional representation system to elect the upper house, the Senate.[1]

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Australia |

|---|

|

| Constitution |

|

The timing of elections is governed by the Constitution and political conventions. Generally, elections are held approximately every three years and are conducted by the independent Australian Electoral Commission (AEC).

Conduct of elections

Federal elections, by-elections and referendums are conducted by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC).

Voter registration

In Australia, voter registration is called enrolment, which is a prerequisite for voting at federal elections, by-elections and referendums. Enrolment is compulsory for Australian citizens over 18 years of age who have lived at their current address for at least one month.[2] Residents in Australia who had been enrolled as British subjects on 25 January 1984, though not Australian citizens, continue to be enrolled. They cannot opt out of enrolment, and must keep their details updated, and vote. (These comprise about 9% of enrolments.)

Electoral rolls

The AEC maintains a permanent Commonwealth electoral roll. State and local elections are today based upon the Commonwealth electoral roll, maintained under joint roll arrangements,[3] though each state and territory regulates its own part of the electoral roll. The same enrolment application or update form can be used for Commonwealth, state and local rolls.[2]

A protection in Section 101 (8) exists for offences prior to enrolment (including failure to enrol) for those enrolled in such a way by the Electoral Commissioner. Anyone serving a prison sentence of 3 years or more is removed from the federal roll, and must apply to re-enrol upon release.[4]

Enrolment of electors

Special rules apply to citizens going or living outside the country,[2] to military personnel and to prisoners, all of which do not reside at their normal residential address for electoral purposes. Homeless people or those otherwise with no fixed address have a particular problem with registration, not having a current address to give. Enrolment is optional for 16- or 17-year-olds, but they cannot vote until they turn 18.[2] A person can register or update their details online or by mailing in a paper form.

If a change of address causes an individual to move to another electorate (electoral division), they are legally obliged to notify the AEC within 8 weeks. The AEC monitors house and apartment sales and sends a reminder (and the forms) to new residents if they have moved to another electorate, making compliance with the law easier. The AEC conducts periodic door-to-door and postal campaigns to try to ensure that all eligible persons are registered in the correct electorate. An individual has 8 weeks after turning 18 to register and the 8-week period also applies to update of details. Failure to enrol or update details can incur a fine.[5]

Closing of electoral rolls before an election

Federal and state electoral rolls are closed for new enrolments or update of details before each election. For federal elections they are closed 7 days after the issue of writs for election.[6][7] The closing dates vary for state and territory elections. Historically, most new applications and updates are received after an election is called, before the closing of rolls.

Public funding of political parties

To receive federal public funding, a political party must be registered under the Electoral Act, which requires that they have at least 1500 members. All nominations for party-endorsed candidates must be signed by the Registered Officer of a registered party. The name of registered parties appear on ballot papers. Separate registers of parties are maintained for each state and territory, with their own membership requirements.

To receive public funding, a candidate (party-endorsed or independent) must receive at least 4% of the first preference vote in the division or the state or territory they contested.[8]

Nomination

Candidates for either house must formally nominate with the Electoral Commission. The nomination for a party-endorsed candidate must be signed by the Registered Officer of a party registered under the Electoral Act. Fifty signatures of eligible voters are required for an independent candidate.

A deposit of $2,000 is required for a candidate for the House of Representatives or the Senate. (Before March 2019, the deposit for the House of Representatives was $1,000.) This deposit is refunded if the candidate is elected or gains at least 4% of the first preference vote.[9][10]

Between 10 and 27 days must be allowed after the issue of writs before the close of nominations.[11]

The name and political affiliation of candidates who are disendorsed by or resign from a party after the close of nominations, continue to appear on the ballot paper, and they stand as independents. However, complications arise for senate candidates in that position in respect of voting "above the line" as party lists would also have been registered.

Election day

The date and type of federal election is determined by the Prime Minister – after a consideration of constitutional requirements, legal requirements, as well as political considerations – who advises the Governor-General to set the process in motion by dissolving either or both houses and issuing writs for election for the House of Representatives and territorial senators. The Constitution of Australia does not require simultaneous elections for the Senate and the House of Representatives, but it has long been preferred that elections for the two houses take place simultaneously. The most recent House-only election took place in 1972, and the most recent Senate-only election took place in 1970. The last independently dated Senate election writ occurred during the Gair Affair in 1974. Federal elections must be held on a Saturday[12] which has been the case since the 1913 federal election.[13]

Subject to those considerations, an election for the House of Representatives can be called at any time before the expiration of the three-year term of the House of Representatives[14][15] The term of the House of Representatives starts on the first sitting day of the House following its election and runs for a maximum of three years, but the House can be dissolved earlier.[14] The date of the first sitting can be extended provided that "There shall be a session of the Parliament once at least in every year, so that twelve months shall not intervene between the last sitting of the Parliament in one session and its first sitting in the next session, but subject to the requirement that the House shall meet not more than 30 days after the date appointed for the return of the writs."[16] The actual date of the election is later. Between 10 and 27 days must be allowed for nominations,[11] and the actual election would be set between 21 and 31 days after the close of nominations.[17] Accordingly, between 31 and 58 must be allowed after the issue of the writs to the election.

The term of senators ends on 30 June either three (for half the senators if it follows a double-dissolution) or six years after their election. Elections of senators at a half-Senate election must take place in the year before the terms expire, except if parliament is dissolved earlier.[18] The terms of senators from the territories align with House elections. The latest date that a half-Senate election can be held must allow time for the votes to be counted and the writs to be returned before the newly elected senators take office on 1 July. This took over a month in 2016, so practically, the date in which a half-Senate election is to take place must be between 1 July of the year before Senate terms expire until mid-May of the expiry year.

A double dissolution cannot take place within six months before the date of the expiry of the House of Representatives.[19]

Constitutional and legal provisions

The Constitutional and legal provisions which impact on the choice of election dates include:[20]

- Section 12 of the Constitution says: "The Governor of any State may cause writs to be issued for the election of Senators for that State"

- Section 13 of the Constitution provides that the election of senators shall be held in the period of twelve months before the places become vacant.

- Section 28 of the Constitution says: "Every House of Representatives shall continue for three years from the first sitting of the House, and no longer, but may be sooner dissolved by the Governor-General."[21] Since the 46th Parliament of Australia opened on 2 July 2019, it will expire on 1 July 2022.

- Section 32 of the Constitution says: "The writs shall be issued within ten days from the expiry of a House of Representatives or from the proclamation of a dissolution thereof." Ten days after 1 July 2022 is 11 July 2022.

- Section 156 (1) of the CEA says: "The date fixed for the nomination of the candidates shall not be less than 10 days nor more than 27 days after the date of the writ".[11] Twenty-seven days after 11 July 2022 is 7 August 2022.

- Section 157 of the CEA says: "The date fixed for the polling shall not be less than 23 days nor more than 31 days after the date of nomination".[17] Thirty-one days after 7 August 2022 is 7 September 2022, a Wednesday.

- Section 158 of the CEA says: "The day fixed for the polling shall be a Saturday".[12] The Saturday before 7 September 2022 is 3 September 2022. This is therefore the latest possible date for the lower house election.

Voting system

Compulsory voting

Voting is compulsory at federal elections, by-elections and referendums for those on the electoral roll, as well as for State and Territory elections. Australia enforces compulsory voting.[22] People in this situation are asked to explain their failure to vote. If no satisfactory reason is provided (for example, illness or religious prohibition), a fine of up to $170 is imposed,[23] and failure to pay the fine may result in a court hearing and additional costs. About 5% of enrolled voters fail to vote at most elections. In South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia voting at local elections is not compulsory.[24] In the other states, local council elections are also compulsory.[25]

Compulsory voting was introduced for the Queensland state election in 1915, for federal elections since the 1925 federal election,[26] and Victoria introduced it for the Legislative Assembly at the 1927 state election and for Legislative Council elections in 1935.[27] New South Wales and Tasmania introduced compulsory voting in 1928, Western Australia in 1936 and South Australia in 1942.[28]

Though the immediate justification for compulsory voting at the federal level was the low voter turnout (59.38%)[29] at the 1922 federal election, down from 71.59% at the 1919 federal election, its introduction was a condition of the Country Party agreeing to form an alliance with the then minority Nationalist Party. Compulsory voting was not on the platform of either the Stanley Bruce-led Nationalist/Country party coalition government or the Matthew Charlton-led Labor opposition. The change took the form of a private member's bill initiated by Herbert Payne, a backbench Tasmanian Nationalists senator, who on 16 July 1924 introduced the bill in the Senate. Payne's bill was passed with little debate (the House of Representatives agreeing to it in less than an hour), and in neither house was a division required, hence no votes were recorded against the bill.[30] It received Royal Assent on 31 July 1924 as the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1924.[31] The 1925 federal election was the first to be conducted under compulsory voting, which saw the turnout rise to 91.4%. The turnout increased to about 95% within a couple of elections and has stayed at about that level since. Compulsory voting at referendums was considered when a referendum was proposed in 1915, but, as the referendum was never held, the idea was put on hold.[29]

It is an offence to "mislead an elector in relation to the casting of his vote". An "informal vote" is a ballot paper that does not indicate a clear voting preference, is left blank, or carries markings that might identify the voter.[32] The number of informal votes is counted but, in the determination of voter preferences, they are not included in the total number of (valid) votes cast. Around 95% of registered voters attend polling, and around 5% of House of Representatives votes are informal.[33][34]

When compulsory voting was introduced in Victoria in 1926 for the Legislative Assembly, the turnout increased from 59.24% at the 1924 state election to 91.76% at the 1927 state election, but the informal vote increased from 1.01% in 1924 to 1.94% in 1927. But when it was introduced for the 1937 Legislative Council election, which was not held on the same day as for the Legislative Assembly, the turnout increased from 10% to only 46%.

The requirement is for the person to enrol, attend a polling station and have their name marked off the electoral roll as attending, receive a ballot paper and take it to an individual voting booth, mark it, fold the ballot paper and place it in the ballot box. There is no explicit requirement for a choice to be made, the ballot paper is only to be 'marked'. According to the act, how a person marks the paper is completely up to the individual. Despite the risk of sanctions, the voter turnout at federal elections is dropping, with 1.4 million eligible voters, or nearly 10% of the total, failing to vote at the 2016 federal election, the lowest turnout since compulsory voting began.[35] At the 2010 Tasmanian state election, with a turnout of 335,353 voters, about 6,000 people were fined $26 for not voting, and about 2,000 paid the fine.[36] A postal vote is available for those for whom it is difficult to attend a polling station. Early, or pre-poll, voting at an early voting centre is also available for those who might find it difficult to get to a polling station on election day.[37]

Debate over compulsory voting

Following the 2004 federal election, at which the Liberal–National coalition government won a majority in both houses, a senior minister, Senator Nick Minchin, said that he favoured the abolition of compulsory voting. Some prominent Liberals, such as Petro Georgiou, former chair of the Parliament's Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, have spoken in favour of compulsory voting.

Peter Singer, in Democracy and Disobedience, argues that compulsory voting could negate the obligation of a voter to support the outcome of the election, since voluntary participation in elections is deemed to be one of the sources of the obligation to obey the law in a democracy. In 1996 Albert Langer was jailed for three weeks on contempt charges in relation to a constitutional challenge on a legal way not to vote for either of the major parties. Chong, Davidson and Fry, writing in the journal of the right wing think tank the CIS, argue that Australian compulsory voting is disreputable, paternalistic, disadvantages smaller political parties, and allows major parties to target marginal seats and make some savings in pork-barrelling because of this targeting. Chong et al. also argue that denial is a significant aspect of the debate about compulsory voting.[38]

A counter argument to opponents of compulsory voting is that in these systems the individual still has the practical ability to abstain at the polls by voting informally if they so choose, due to the secrecy of the ballot. A spoilt vote does not count towards any political party and effectively is the same as choosing not to vote under a non-compulsory voting system. However, Singer argues that even the appearance of voluntary participation is sufficient to create an obligation to obey the law.

In the 2010 Australian election, Mark Latham urged Australians to vote informally by handing in blank ballot papers for the 2010 election. He also stated that he feels it is unfair for the government to force citizens to vote if they have no opinion or threaten them into voting with a fine.[39] An Australian Electoral Commission spokesman stated that the Commonwealth Electoral Act did not contain an explicit provision prohibiting the casting of a blank vote.[40] How the Australian Electoral Commission arrived at this opinion is unknown; it runs contrary to the opinions of Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick, who wrote that voters must actually mark the ballot paper and deposit that ballot into a ballot box, and Justice Blackburn who was of the opinion that casting an invalid vote was a violation of the Act.[38]

Tim Evans, a Director of Elections Systems and Policy of the AEC, wrote in 2006 that "It is not the case, as some people have claimed, that it is only compulsory to attend the polling place and have your name marked off and this has been upheld by a number of legal decisions."[41] Yet, practically, it remains the fact that having received a ballot paper, the elector can simply fold it up and put it into the ballot box without formally marking it, if the elector objects, in principle, to casting a vote. However, the consistently low number of informal votes each election indicates that having attended, had his or her name marked off, very few electors then choose not to vote formally.

Compulsory voting has also been promoted for its collective benefits. It becomes difficult for coercion to be used to prevent disadvantaged people (the old, illiterate or disabled) to vote, and for obstacles to be put in the way of classes of individuals (ethnic/coloured; either registration requirements or placement of voting booths) as often happens under other voting systems. The compulsion requirement also needs to be kept in proportion: jury duty and compulsory military service are vastly more onerous citizen's compulsions than attending a local voting booth once every few years. Perhaps the most compelling reason to use a system of compulsory voting is a simple matter of logistics, that is, to facilitate the smooth and orderly process of an election. Every year in countries that do not have compulsory voting election officials have to guess at the numbers of voters who might turn out – this often depends on the vagaries of the weather. Often voters are disenfranchised in those countries when voting officials err and not enough voting booths are provided. Long queues can result with voters being turned away at the close of polling, not having had their chance to exercise their democratic right to vote.

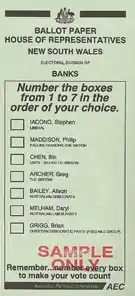

Ranked (or preferential) voting

Australia uses various forms of ranked voting for almost all elections. Under this system, voters number the candidates on the ballot paper in the order of their preference. The preferential system was introduced for federal elections in 1918, in response to the rise of the Country Party, a party representing small farmers. The Country Party split the anti-Labor vote in conservative country areas, allowing Labor candidates to win on a minority vote. The conservative federal government of Billy Hughes introduced preferential voting as a means of allowing competition between the two conservative parties without putting seats at risk.[42] It was first used in the form of instant-runoff voting at the Corangamite by-election on 14 December 1918.[43][44] The system was first used for election for the Queensland Parliament in 1892. In the form of Single transferable voting, ranked voting was introduced in the Tasmanian House of Assembly in 1906 as a result of the work of Andrew Inglis Clark and Catherine Helen Spence, building on the original concept invented in 1859 by Briton Thomas Hare.

Preferential voting has gradually extended to both upper and lower houses, in the federal, state and territory legislatures, and is also used in municipal elections, and most other kinds of elections as well, such as internal political party elections, trade union elections, church elections, elections to company boards and elections in voluntary bodies such as football clubs. Negotiations for disposition of preference recommendations to voters are taken very seriously by candidates because transferred preferences carry the same weight as primary votes. (A vote is only transferred if use of the earlier preference means the ballot cannot be used effectively.)

Political parties usually produce how-to-vote cards to assist and guide voters in the ranking of candidates. When parties declare how they are preferencing other parties, typically in the lead-up to an election, they are declaring how they will instruct their supporters via these cards: there is no mechanism in the electoral system for inter-party preferences.[45]

Secret balloting

Secret balloting was implemented by Tasmania, Victoria and South Australia in 1856,[46] followed by other Australian colonies: New South Wales (1858), Queensland (1859), and Western Australia (1877). Colonial (soon to become States) electoral laws, including the secret ballot, applied for the first election of the Australian Parliament in 1901, and the system has continued to be a feature of all elections in Australia and also applies to referendums.

The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 does not explicitly set out the secret ballot but a reading of sections 206, 207, 325 and 327 of the Act would imply its assumption. Sections 323 and 226(4) do however, apply the principle of a secret ballot to polling staff and would also support the assumption.

Proxy voting is not permitted at federal and state elections.

Alternative voting methods

Most voting takes place with registered voters attending a polling station on election day, where they are given a ballot paper which they mark in a prescribed manner and then place it into a ballot box. However, alternative voting methods are available. For example, a person may vote by an absentee ballot whereby a voter attends a voting place which is not in the electoral district in which they are registered to vote. Instead of marking the ballot paper and putting it in the ballot box, the voter's ballot paper is placed in an envelope and then it is sent by the voting official to the voter's home district to be counted there. Other alternatives are postal voting and early voting, known as "pre-poll voting", which are also available to voters who would not be in their registered electoral districts on an election day.

A form of postal voting was introduced in Western Australia in 1877, followed by an improved method in South Australia in 1890.[47] On the other hand, concerns about postal voting have been raised as to whether it complies with the requirements of a secret ballot, in that people cast their vote outside the security of a polling station, and whether voters can cast their vote privately free from another person's coercion.

In voting for the Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly, voters may choose between voting electronically or on paper.[48] Otherwise, Australian elections are carried out using paper ballots. If more than one election takes place, for example for the House of Representatives and the Senate, then each election is on a separate ballot paper, which are of different colours and which are deposited into separate ballot boxes.

Allocation process

Allocation process for House of Representatives

The main elements of the operation of preferential voting for single-member House of Representatives divisions are as follows:[49][50]

- Voters are required to place the number "1" against their first choice of candidate, known as the "first preference" or "primary vote".

- Voters are then required to place the numbers "2", "3", etc., against all of the other candidates listed on the ballot paper, in order of preference. (Every candidate must be numbered, otherwise the vote becomes "informal" (spoiled) and does not count.[51])

- Prior to counting, each ballot paper is examined to ensure that it is validly filled in (and not invalidated on other grounds).

- The number "1" or first preference votes are counted first. If no candidate secures an absolute majority (more than half) of first preference votes, then the candidate with the fewest votes is excluded from the count.

- The votes for the eliminated candidate (i.e., from the ballots that placed the eliminated candidate first) are re-allocated to the remaining candidates according to the number "2" or "second preference" votes.

- If no candidate has yet secured an absolute majority of the vote, then the next candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. This preference allocation is repeated until there is a candidate with an absolute majority. Where a second (or subsequent) preference is expressed for a candidate who has already been eliminated, the voter's third or subsequent preferences are used.

Following the full allocation of preferences, it is possible to derive a two-party-preferred figure, where the votes have been allocated between the two main candidates in the election. In Australia, this is usually between the candidates from the Coalition parties and the Australian Labor Party.

Alternative allocation methods for Senate

For the Australian Senate, each State constitutes one multi-member electorate. Currently, 12 senators are elected from each State, one half every three years, except in the case of double dissolution when elections for all 12 senators in each State take place. The number of senators to be elected determines the 'quota' required to be achieved for election by quota-preferential voting.[52] For a half-Senate election of 6 places to be filled, the quota in each State is 14.28% (calculated using the formula 1/(6+1)), while after a double dissolution the quota is 7.69% (calculated using the formula 1/(12+1)). The AEC also conducts a special recount after a double dissolution using a half-Senate quota for the purpose of allocating long and short terms so that rotation of senators can be re-established, however the Senate has never used the results to allocate terms, despite two bipartisan senate resolutions to use it.

The federal Senate electoral system from 1984 to 2013, and those currently used for some state legislatures, provide for simultaneous registration of party-listed candidates and party-determined orders of voting preference, known as 'group voting tickets' or 'above the line voting' which involves placing the number '1' in a single box and the vote is then allocated in accordance with the party's registered voting preferences. The AEC automatically allocates preferences, or votes, in the predetermined order outlined in the group voting ticket. Each party or group can register up to three group voting tickets. This highly complex system has potential for unexpected outcomes,[53] including the possible election of a candidate who may have initially received an insignificant primary vote tally (see, for example, the Minor Party Alliance at the 2013 federal election). An estimated 95% of all votes are cast 'above the line'.[54]

The alternative for Senate elections from 1984 to 2013 was to use 'below the line voting' by numbering a large number of individual candidate's boxes in the order of the voter's preference. To be valid, the voter placed sequential numbers against every candidate on the ballot paper, and the risk of error and invalidation of the vote was significant.

In 2016, the Senate voting system was changed again to abolish group voting tickets and introduce optional preferential voting. An "above the line" vote for a party now allocates preferences to the candidates of that party only, in the order in which they are listed. The AEC directs voters to number 6 or more boxes above the line. If, instead, voters choose to vote for individual candidates in their own order of preference "below the line", at least 12 boxes must be numbered. (See also Australian Senate#Electoral system).[55][56]

Gerrymandering and malapportionment

Malapportionment occurs when the numbers of voters in electorates are not equal. Malapportionment can occur through demographic change or through the deliberate weighting of different zones, such as rural v. urban areas. Malapportionment differs from a gerrymander, which occurs when electoral boundaries are drawn to favour one political party or group over others.

There is no scope for malapportionment of Senate divisions, with each State constituting one multi-member electorate, though no account is taken of differences in the relative populations of states.

For the House of Representatives, members are elected from single member electorates.

Australia has seen very little gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, relevant only for the House of Representatives and State Legislative Assemblies, which have nearly always been drawn up by public servants or independent boundary commissioners. But Australia has seen systematic malapportionment of electorates. All colonial legislatures before Federation, and the federal parliament after it, allocated more representation to rural districts than their populations merited. This was justified on several grounds, such as that country people had to contend with greater distances and hardships, that country people (and specifically farmers) produced most of the nation's real wealth, and that greater country representation was necessary to balance the radical tendencies of the urban population.

However, in the later 20th century, these arguments were successfully challenged, and by the early 21st century malapportionment was abolished in all states. In all states, electoral districts must have roughly the same number of voters, with variations allowed for rural areas due to their sparse population. Proponents of this concept call this "one vote, one value".

For the 2019 Federal election, most electorates contained between 105,000 and 125,000 voters. However, in Tasmania 5 electorates contained between 73,000 and 80,000 voters, because the Constitution (s.24) grants Tasmania a minimum of 5 members in the House of Representatives.

Examples

The most conspicuous examples of malapportionment were those of South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia.

South Australia

In South Australia, the 1856 Constitution stipulated that there must be two rural constituencies for every urban constituency.

By the early 1960s, the urban-rural voter ratio was almost exactly reversed: more than two-thirds of the state's population lived in Adelaide and its suburbs, but the rural areas elected two-thirds of the legislature. This was despite the fact that by this time, rural seats had on average one-quarter as many voters as urban seats: in one of the more extreme cases, a vote in the rural seat of Frome was worth 10 times a vote in an Adelaide seat.

The setup allowed the Liberal and Country League to stay in office from 1932 to 1965, the last 27 of these under Thomas Playford. However, from 1947, the LCL lost by increasing margins in terms of actual votes, and in 1953, even retained power despite losing the two-party vote and Labor winning a majority of the primary vote. Largely because Playford was the main beneficiary, the setup was called "the Playmander", although it was not strictly speaking a gerrymander.

The gross inequities of this system came into sharp focus during three consecutive state elections in the 1960s:

- In 1962, Labor won 54.3% of the two party vote, a margin normally large enough for a comprehensive victory, but came up one seat short of a majority as it only managed a two-seat swing, and Playford was able to continue in power with the support of two independents.

- While the Playmander was overcome when Labor defeated the LCL in 1965, the rural weighting was strong enough that Labor won only a one-seat majority, despite winning 54.3% of the two-party vote.

- In 1968, the LCL regained power despite Labor winning the popular vote with 53.2% to the LCL's 46.8%, as Labor suffered a two-seat swing, leaving both parties with 19 seats each before conservative independent Tom Stott threw his support to the LCL for a majority.

Playford's successor as LCL leader, Steele Hall, was highly embarrassed at the farcical manner in which he became Premier, and immediately set about enacting a fairer system: a few months after taking office, Hall enacted a new electoral map with 47 seats: 28 seats in Adelaide and 19 in the country.

Previously, there had been 39 seats (13 in Adelaide and 26 in country areas), but, for some time, the LCL's base in Adelaide had been limited to the wealthy eastern crescent and the area around Holdfast Bay.

While it came up slightly short of "one vote, one value", as Labor had demanded, the new system allowed Adelaide to elect a majority of the legislature, which all but assured a Labor victory at the next election; despite this, Hall knew he would be effectively handing the premiership to his Labor counterpart, Don Dunstan.

In the first election under this system, in 1970, Dunstan won handily, picking up all eight new seats.

After Premier Don Dunstan introduced the Age of Majority (Reduction) Bill in October 1970, the voting age in South Australia was lowered to 18 years old in 1973.

Queensland

In Queensland, the malapportionment initially benefitted the Labor Party, since many small rural constituencies were dominated by workers in provincial cities who were organised into the powerful Australian Workers' Union. But after 1957, the Country Party (later renamed the National Party) governments of Sir Frank Nicklin and Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen tweaked the system to give the upper hand to their rural base and isolate Labor support in Brisbane and provincial cities. In later years, this system made it possible for Bjelke-Petersen to win elections with only a quarter of the first preference votes. On average, a Country/National seat took only 7,000 votes to win, compared with 12,000 for a Labor seat. Combined with the votes of the Liberals (in Queensland, the National Party had historically been the senior partner in the non-Labor coalition), this was enough to lock Labor out of power even in years when Labor was the biggest single party in the legislature. This "Bjelkemander" was not overcome until the final defeat of the Nationals in 1989. Under new Labor premier Wayne Goss, a revised map was enacted with 40 seats in Brisbane and 49 in the country. Seats had roughly the same number of voters, with a greater tolerance allowed for seats in rural areas.

Western Australia

Western Australia retained a significant malapportionment in the Legislative Assembly until 2008. Under the previous system, votes in the country were worth up to four times the value of votes in Perth, the state's capital city. On 20 May 2005 the state Parliament passed new electoral laws, removing the malapportionment with effect from the following election. Under the new laws, electorates must have a population of 21,343, with a permitted variation of 10%. Electorates with a land area of more than 100,000 km2 (39,000 sq mi) are permitted to have a variation of 20%, in recognition of the difficulty of representing the sparsely populated north and east of the state.[57] Large districts would be attributed an extra number of notional voters, equal to 1.5% the area of the district in square kilometres, for the purposes of this calculation. This Large District Allowance will permit large rural districts to have many fewer voters than the average district enrolment. The Office of the Electoral Distribution Commissioners[58] gives the following example: Central Kimberley-Pilbara district has 12601 electors and an area of 600038 square kilometres. The average district enrolment for WA is 21343. Central Kimberley-Pilbara thus obtains 9000 notional extra electors, bringing its notional total to 21601, which is acceptably close to the average district enrolment.

A modified form of malapportionment was, however, retained for the Legislative Council, the state upper house. Rural areas are still slightly overrepresented, with as much as six times the voting power of Perth on paper.[59] According to ABC election analyst Antony Green, the rural weighting in the Legislative Council is still significant enough that a Liberal state premier has no choice but to include the National Party in his government, even if the Liberals theoretically have enough seats in the Legislative Assembly to govern alone.[60]

The Parliament

The Parliament of Australia is a bicameral (two-house) parliament. It combines some of the features of the Parliament of the United Kingdom with some features of the United States Congress. This is because the authors of the Australian Constitution had two objectives: to reproduce as faithfully as possible the Westminster system of parliamentary government, while creating a federation in which there would be a division of powers between the national government and the states, regulated by a written constitution.

In structure, the Australian Parliament resembles the United States Congress. There is a House of Representatives elected from single-member constituencies of approximately equal population, and there is a Senate consisting of an equal number of senators from each state, regardless of population (since 1975 there have also been senators representing the territories).

But in function, the Australian Parliament follows the Westminster system. The Prime Minister holds office because he can command the support of the majority of the House of Representatives, and must resign or advise an immediate election if the house passes a vote of no-confidence in his administration. If he fails to do so, he risks dismissal by the Governor-General. All ministers are required to be members of Parliament (although the constitution permits a person who is not currently a member of parliament to hold a ministerial portfolio for a maximum period of three months).

The House of Representatives

The Australian House of Representatives has 151 members elected from single-member constituencies (formally called "Electoral Divisions", but usually called seats or electorates in Australia; see Australian electorates) for three-year terms. Voters must fill in the ballot paper by numbering all the candidates in order of their preference. Failure to number all the candidates, or an error in numbering, renders the ballot informal (invalid).[61] The average number of candidates has tended to increase in recent years: there are frequently 10 or 12 candidates in a seat, and at the Wills by-election in April 1992 there were 22 candidates.[62] This has made voting increasingly onerous, but the rate of informal voting has increased only slightly.

The low rate of informal voting is largely attributed to advertising from the various political parties indicating how a voter should number their ballot paper, called a How-to-Vote Card. On election day, volunteers from political parties stand outside polling places, handing voters a card which advises them how to cast their vote for their respective party. Thus, if a voter wishes to vote for the Liberal Party, they may take the Liberal How-to-Vote Card and follow its instructions. While they can lodge their vote according to their own preferences, Australian voters show a high degree of party loyalty in following their chosen party's card.

A disinterested voter who has formed no personal preference may simply number all the candidates sequentially, 1, 2, 3, etc., from top to bottom of the ballot paper, a practice termed donkey voting, which advantages those candidates whose names are placed nearest to the top of the ballot paper. Before 1984, candidates were listed in alphabetical order, which led to a profusion of Aaronses and Abbotts contesting elections. A notable example was the 1937 Senate election, in which the Labor candidate group in New South Wales consisted of Amour, Ashley, Armstrong and Arthur—all of whom were elected. Since 1984, the listed order of candidates on the ballot paper has been determined by drawing lots, a ceremony performed publicly by electoral officials immediately after the appointed time for closure of nominations.

Lower house primary, two-party and seat results since 1910

A two-party system has existed in the Australian House of Representatives since the two non-Labor parties merged in 1909. The 1910 election was the first to elect a majority government, with the Australian Labor Party concurrently winning the first Senate majority. A two-party-preferred vote (2PP) has been calculated since the 1919 change from first-past-the-post to preferential voting and subsequent introduction of the Coalition. ALP = Australian Labor Party, L+NP = grouping of Liberal/National/LNP/CLP Coalition parties (and predecessors), Oth = other parties and independents.

| Primary vote | 2PP vote | Seats | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALP | L+NP | Oth. | ALP | L+NP | ALP | L+NP | Oth. | Total | |

| 18 May 2019 election | 33.3% | 41.4% | 25.2% | 48.5% | 51.5% | 68 | 77 | 6 | 151 |

| 2 July 2016 election | 34.7% | 42.0% | 23.3% | 49.6% | 50.4% | 69 | 76 | 5 | 150 |

| 7 September 2013 election | 33.4% | 45.6% | 21.1% | 46.5% | 53.5% | 55 | 90 | 5 | 150 |

| 21 August 2010 election | 38.0% | 43.3% | 18.8% | 50.1% | 49.9% | 72 | 72 | 6 | 150 |

| 24 November 2007 election | 43.4% | 42.1% | 14.5% | 52.7% | 47.3% | 83 | 65 | 2 | 150 |

| 9 October 2004 election | 37.6% | 46.7% | 15.7% | 47.3% | 52.7% | 60 | 87 | 3 | 150 |

| 10 November 2001 election | 37.8% | 43.0% | 19.2% | 49.0% | 51.0% | 65 | 82 | 3 | 150 |

| 3 October 1998 election | 40.1% | 39.5% | 20.4% | 51.0% | 49.0% | 67 | 80 | 1 | 148 |

| 2 March 1996 election | 38.7% | 47.3% | 14.0% | 46.4% | 53.6% | 49 | 94 | 5 | 148 |

| 13 March 1993 election | 44.9% | 44.3% | 10.7% | 51.4% | 48.6% | 80 | 65 | 2 | 147 |

| 24 March 1990 election | 39.4% | 43.5% | 17.1% | 49.9% | 50.1% | 78 | 69 | 1 | 148 |

| 11 July 1987 election | 45.8% | 46.1% | 8.1% | 50.8% | 49.2% | 86 | 62 | 0 | 148 |

| 1 December 1984 election | 47.6% | 45.0% | 7.4% | 51.8% | 48.2% | 82 | 66 | 0 | 148 |

| 5 March 1983 election | 49.5% | 43.6% | 6.9% | 53.2% | 46.8% | 75 | 50 | 0 | 125 |

| 18 October 1980 election | 45.2% | 46.3% | 8.5% | 49.6% | 50.4% | 51 | 74 | 0 | 125 |

| 10 December 1977 election | 39.7% | 48.1% | 12.2% | 45.4% | 54.6% | 38 | 86 | 0 | 124 |

| 13 December 1975 election | 42.8% | 53.1% | 4.1% | 44.3% | 55.7% | 36 | 91 | 0 | 127 |

| 18 May 1974 election | 49.3% | 44.9% | 5.8% | 51.7% | 48.3% | 66 | 61 | 0 | 127 |

| 2 December 1972 election | 49.6% | 41.5% | 8.9% | 52.7% | 47.3% | 67 | 58 | 0 | 125 |

| 25 October 1969 election | 47.0% | 43.3% | 9.7% | 50.2% | 49.8% | 59 | 66 | 0 | 125 |

| 26 November 1966 election | 40.0% | 50.0% | 10.0% | 43.1% | 56.9% | 41 | 82 | 1 | 124 |

| 30 November 1963 election | 45.5% | 46.0% | 8.5% | 47.4% | 52.6% | 50 | 72 | 0 | 122 |

| 9 December 1961 election | 47.9% | 42.1% | 10.0% | 50.5% | 49.5% | 60 | 62 | 0 | 122 |

| 22 November 1958 election | 42.8% | 46.6% | 10.6% | 45.9% | 54.1% | 45 | 77 | 0 | 122 |

| 10 December 1955 election | 44.6% | 47.6% | 7.8% | 45.8% | 54.2% | 47 | 75 | 0 | 122 |

| 29 May 1954 election | 50.0% | 46.8% | 3.2% | 50.7% | 49.3% | 57 | 64 | 0 | 121 |

| 28 April 1951 election | 47.6% | 50.3% | 2.1% | 49.3% | 50.7% | 52 | 69 | 0 | 121 |

| 10 December 1949 election | 46.0% | 50.3% | 3.7% | 49.0% | 51.0% | 47 | 74 | 0 | 121 |

| 28 September 1946 election | 49.7% | 39.3% | 11.0% | 54.1% | 45.9% | 43 | 26 | 5 | 74 |

| 21 August 1943 election | 49.9% | 23.0% | 27.1% | 58.2% | 41.8% | 49 | 19 | 6 | 74 |

| 21 September 1940 election | 40.2% | 43.9% | 15.9% | 50.3% | 49.7% | 32 | 36 | 6 | 74 |

| 23 October 1937 election | 43.2% | 49.3% | 7.5% | 49.4% | 50.6% | 29 | 44 | 2 | 74 |

| 15 September 1934 election | 26.8% | 45.6% | 27.6% | 46.5% | 53.5% | 18 | 42 | 14 | 74 |

| 19 December 1931 election | 27.1% | 48.4% | 24.5% | 41.5% | 58.5% | 14 | 50 | 11 | 75 |

| 12 October 1929 election | 48.8% | 44.2% | 7.0% | 56.7% | 43.3% | 46 | 24 | 5 | 75 |

| 17 November 1928 election | 44.6% | 49.6% | 5.8% | 48.4% | 51.6% | 31 | 42 | 2 | 75 |

| 14 November 1925 election | 45.0% | 53.2% | 1.8% | 46.2% | 53.8% | 23 | 50 | 2 | 75 |

| 16 December 1922 election | 42.3% | 47.8% | 9.9% | 48.8% | 51.2% | 29 | 40 | 6 | 75 |

| 13 December 1919 election | 42.5% | 54.3% | 3.2% | 45.9% | 54.1% | 25 | 38 | 2 | 75 |

| 5 May 1917 election | 43.9% | 54.2% | 1.9% | – | – | 22 | 53 | 0 | 75 |

| 5 September 1914 election | 50.9% | 47.2% | 1.9% | – | – | 42 | 32 | 1 | 75 |

| 31 May 1913 election | 48.5% | 48.9% | 2.6% | – | – | 37 | 38 | 0 | 75 |

| 13 April 1910 election | 50.0% | 45.1% | 4.9% | – | – | 42 | 31 | 2 | 75 |

Counting votes in elections for the House of Representatives

The House of Representatives uses full preferential voting, which is known outside Australia by names such as "instant runoff voting" (IRV) and "alternative voting".

When the polls close at 6 pm on election day, the votes are counted. The count is conducted by officers of the Australian Electoral Commission, watched by nominated volunteer observers from the political parties, called scrutineers, who are entitled to observe the whole voting process from the opening of the booth. The votes from each polling booth in the electorate are tallied at the office of the returning officer for the electorate. If one of the candidates has more than 50% of the vote, then they are declared elected. Australian politics are influenced by social and economic demographics, though the correlation between "class" and voting is not always simple.[63] Typically, the National Party will poll higher in rural seats. The Liberal Party and the Australian Labor Party are not as easily generalised. In a strong seat, the elected party might win up to 80% of the two-party-preferred vote. In the 2004 federal election, the highest winning margin in a seat was 25.1%,[64] with most seats won by a margin of less than 10%.

In the remaining seats, no single candidate will have a majority of the primary votes (or first-preference votes). A hypothetical result might look like this:

White (Democrat) 6,000 6.0% Smith (Labor) 45,000 45.0% Jones (Liberal) 35,000 35.0% Johnson (Green) 10,000 10.0% Davies (Ind) 4,000 4.0%

On election night, an interim distribution of preferences called a TCP (two-candidate-preferred) count is performed. The electoral commission nominates the two candidates it believes are most likely to win the most votes and all votes are distributed immediately to one or the other preferred candidate.[65] This result is indicative only and subsequently the formal count will be performed after all "declaration" (e.g. postal, absent votes) votes are received.

In this example, the candidate with the smallest vote, Davies, will be eliminated, and his or her preferences will be distributed: that is, his or her 4,000 votes will be individually re-allocated to the remaining candidates according to which candidate received the number 2 vote on each of those 4000 ballot papers. Suppose Davies's preferences split 50/50 between Smith and Jones. After re-allocation of Davies's votes, Smith would have 47% and Jones 37% of the total votes in the electorate. White would then be eliminated. Suppose all of White's preferences went to Smith. Smith would then have 53% and would be declared elected. Johnson's votes would not need to be distributed.

Exhausted preferences

The exhausted counts correspond to votes that ought to be informal, if strictly following the rules above, but were deemed to have expressed some valid preferences. The Electoral Act has since been amended to almost eliminate exhausted votes.

Section 268(1)(c) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 now has the effect of making the vote of any elector that does not preference every candidate on the ballot paper an informal vote as opposed to counting the vote until the voter's preference exhausts.

Two-party majorities, swings and pendulums

Since 1984 the preferences of all candidates in House of Representatives seats have been distributed, even if this is not necessary to determine the winner of the seat. This is done to determine the percentage of the votes obtained by the winning candidate after the distribution of all preferences. This is called the two-party-preferred vote. For example, if (in the example given above), Smith finished with 58% of the vote after the distribution of Johnson's preferences, Smith's two-party vote would be 58% and the seat would be said to have a two-party majority of 8%. It would therefore need a two-party swing of 8 percentage points to be lost to the other side of politics at the next election.

Once the two-party majorities in all seats are known, they can then be arranged in a table to show the order in which they would be lost in the event of an adverse swing at the next election. Such tables frequently appear in the Australian media and are called election pendulums or sometimes Mackerras pendulums after the political scientist Malcolm Mackerras, who popularised the idea of the two-party vote in his 1972 book Australian General Elections.

Here is a sample of the federal election pendulum from the 2001 election, showing some of the seats held by the Liberal-National Party coalition government, in order of their two-party majority. A seat with a small two-party majority is said to be a marginal seat or a swinging seat. A seat with a large two-party majority is said to be a safe seat, although "safe" seats have been known to change hands in the event of a large swing.

| Seat | State | Majority | Member | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinkler | Qld | 0.0 | Paul Neville | NPA |

| Solomon | NT | 0.1 | Dave Tollner | Lib |

| Adelaide | SA | 0.2 | Hon Trish Worth | Lib |

| Canning | WA | 0.4 | Don Randall | Lib |

| Dobell | NSW | 0.4 | Ken Ticehurst | Lib |

| Parramatta | NSW | 1.1 | Ross Cameron | Lib |

| McEwen | Vic | 1.2 | Fran Bailey | Lib |

| Paterson | NSW | 1.4 | Bob Baldwin | Lib |

| Herbert | Qld | 1.6 | Peter Lindsay | Lib |

| Richmond | NSW | 1.6 | Hon Larry Anthony | NPA |

| Deakin | Vic | 1.7 | Philip Barresi | Lib |

| Eden-Monaro | NSW | 1.7 | Gary Nairn | Lib |

| Hindmarsh | SA | 1.9 | Hon Christine Gallus | Lib |

Redistributions

The boundaries of Australian electoral divisions are reviewed periodically by the Australian Electoral Commission and redrawn in a process called redistribution.

The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 requires that all seats have approximately an equal number of enrolled voters. When the Commission determines that population shifts within a state have caused some seats to have too many or too few voters, a redistribution is called and new boundaries are drawn up.

Redistributions are also held when the Commission determines (following a formula laid down in the Electoral Act) that the distribution of seats among the states and territories must be changed because some states are growing faster than others.

House casual vacancies

If a member's seat becomes vacant mid-term, whether through disqualification, resignation, death or some other possible reason, a by-election may be held to fill the casual vacancy. A member may resign by tendering the resignation to the Speaker, as required by section 37 of the Australian Constitution, or in the absence of the Speaker to the Governor-General. A resignation is not effective until it is tendered in writing to the Speaker or Governor-General. If a redistribution has taken place since the last election, the by-election is held on the basis of the boundaries at the time of original election.

Senate

The Australian Senate has 76 members: each of the six states elects 12 senators, and the Northern Territory (NT) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) each elect two senators. The several other Australian Territories have very small populations and are represented by Northern Territory and ACT Senators (for example, Christmas Island residents are represented by NT Senators, while Jervis Bay Territory and Norfolk Island residents are represented by ACT Senators).

Senators for the states serve six-year terms, with half the senators from each state usually being elected at each federal election. The terms of the territory senators coincide with the duration of the House of Representatives.

The Senate is elected both proportionately and preferentially, except that each state has an equal number of seats so that the distribution of seats to states is non-proportional to the total Australian population. Thus, although within each state the seats proportionally represent the vote for that state, overall the less populous states are proportionally stronger in representation for their population compared to the more populous states.

At the 2013 federal election, the Senate election, contested by over 50 groups,[66] saw extensive "preference deals" (legitimate manipulation of group voting tickets), resulting in the election to the Senate of Ricky Muir from the Australian Motoring Enthusiast Party, who had received only 0.5% of first-preference support.[67] This exploitation of the system was alleged to undermine the entitlement of voters "to be able to make real choices, not forced ones—and to know who they really are voting for".[68]

Following the 2013 election, the Abbott Liberal government announced it would investigate changing the electoral system for the Senate in order to prevent the preference system being abused. On 22 February 2016, the Turnbull Liberal government announced several proposed changes.[69] The changes had the support of the Liberal/National Coalition, the Australian Greens, and Nick Xenophon − a three-vote majority.[70] The Senate reform legislation passed both houses of the Parliament of Australia on 18 March 2016 after the Senate sat all night debating the bill.[71]

The changes abolished group voting tickets and introduced optional preferential voting, along with party logos on the ballot paper. The ballot paper continues to have a box for each party above a heavy line, with each party's candidates in a column below that party's box below the solid line. Previously, a voter could either mark a single box above the line, which triggered the party's group voting ticket (a pre-assigned sequence of preferences), or place a number in every box below the line to assign their own preferences. As a result of the changes, voters may assign their preferences for parties above the line (numbering as many boxes as they wish), or individual candidates below the line, and are not required to fill all of the boxes. Both above and below the line voting are now optional preferential voting. For above the line, voters are instructed to number at least their first six preferences, however, a "savings provision" still counts the ballot if less than six are given. As a result, fewer votes are classed as informal, however, more ballots do "exhaust" as a result (i.e. some votes are not counted towards electing any candidate). For below the line, voters are required to number at least their first 12 preferences. Voters are still free to continue numbering as many preferences as they like beyond the minimum number specified. Another savings provision allows ballot papers with at least 6 below the line preferences to be formal, catering for people who confuse the above and below the line instructions; an additional change to the savings provision will also accept below the line votes with a higher number of sequence errors than previously, treating the sequence as stopping at the first error (missed or repeated numbers).

As a result of these reforms, it is now much less likely that a candidate with such a minuscule primary vote as Muir's in 2013 could win election to the Senate. ABC electoral psephologist Antony Green wrote several publications on various aspects of the proposed Senate reforms.[72][73][74][75][76][77]

Usually, a party can realistically hope to win no more than three of a state's Senate seats. For this reason, a person listed as fourth or lower on a party ticket is said to be in an "unwinnable" position. For example, incumbent Liberal South Australian Senator Lucy Gichuhi was ranked fourth on the Liberal ticket for the 2019 election, a move that commentators believed made it difficult, if not impossible, for her to win another term.[78][79][80]

Senate count

The form of preferential voting used in the Senate is technically known as the "Unweighted Inclusive Gregory Method".[81][82]

The system for counting Senate votes is complicated, and a final result is sometimes not known for several weeks. When the Senate vote is counted, a quota for election is determined. This is the number of valid votes cast, divided by the number of senators to be elected plus one.

For example, here is the Senate result for the state of New South Wales from the 1998 federal election. For greater clarity the votes cast for 50 minor party and independent candidates have been excluded.

The quota for election was 3,755,725 divided by seven, or 536,533.

- Enrolment: 4,031,749

- Turnout: 3,884,333 (96.3%)

- Informal votes: 128,608 (03.3%)

- Formal votes: 3,755,725

- Quota for election: 536,533

| Candidate | Party | Votes | Vote % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor: Group H, Q:2.7073 | ||||

| Steve Hutchins | ALP | 1,446,231 | 38.5 | Elected 1 |

| Hon John Faulkner | ALP | 2,914 | 00.1 | |

| Michael Forshaw | ALP | 864 | 00.0 | |

| Ursula Stephens | ALP | 2,551 | 00.1 | |

| One Nation: Group K, Q:0.6729 | ||||

| David Oldfield | ON | 359,654 | 09.6 | |

| Brian Burston | ON | 570 | 00.0 | |

| Bevan O'Regan | ON | 785 | 00.0 | |

| Liberal: Group L, Q:2.5638 | ||||

| Bill Heffernan | Lib | 1,371,578 | 36.5 | Elected 2 |

| Dr John Tierney | Lib | 1,441 | 00.0 | |

| Sandy Macdonald | NPA | 1,689 | 00.0 | |

| Concetta Fierravanti-Wells | Lib | 855 | 00.0 | |

| Australian Democrats: Group M, Q:0.5142 | ||||

| Aden Ridgeway | AD | 272,481 | 07.3 | |

| Matthew Baird | AD | 457 | 00.0 | |

| Suzzanne Reddy | AD | 2,163 | 00.1 | |

| David Mendelssohn | AD | 809 | 00.0 | |

| Greens: Group U, Q:0.1521 | ||||

| John Sutton | Grn | 80,073 | 02.1 | |

| Catherine Moore | Grn | 748 | 00.0 | |

| Lee Rhiannon | Grn | 249 | 00.0 | |

| Suzie Russell | Grn | 542 | 00.0 | |

In this table, the group number allocated to each list is shown with the number of quotas polled by each list. Thus, "Q:2.7073" next to the Labor Party list indicates that the Labor candidates between them polled 2.7073 quotas.

It will be seen that the leading Labor and Liberal candidates, Hutchins and Heffernan, polled more than the quota. They were therefore elected on the first count. Their surplus votes were then distributed. The surplus is the candidate's vote minus the quota. Hutchins's surplus was thus 1,446,231 minus 536,533, or 909,698. These votes are multiplied by a factor (called the "transfer value") based on the proportion of ballot papers preferencing other parties. ABC Election commentator Antony Green believes that this method distorts preference allocation.[82]

After Hutchins's surplus votes were distributed, the count looked like this:

| Candidate | Votes distributed | % of distributed votes |

Total after distribution | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hutchins | N/A | N/A | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 1 |

| Faulkner | 908,567 | 99.9 | 911,481 | 24.3 | Elected 3 |

| Forshaw | 196 | 00.0 | 1,060 | 00.0 | |

| Stephens | 130 | 00.0 | 2,681 | 00.1 | |

| Oldfield | 186 | 00.0 | 359,840 | 09.6 | |

| Burston | 6 | 00.0 | 576 | 00.0 | |

| O'Regan | 4 | 00.0 | 789 | 00.0 | |

| Heffernan | N/A | N/A | 1,371,578 | 36.5 | Elected 2 |

| Tierney | 13 | 00.0 | 1,454 | 00.0 | |

| Macdonald | 1 | 00.0 | 1,690 | 00.0 | |

| Fierravanti-Wells | 1 | 00.0 | 856 | 00.0 | |

| Ridgeway | 278 | 00.0 | 272,579 | 07.3 | |

| Baird | 5 | 00.0 | 462 | 00.0 | |

| Reddy | 3 | 00.0 | 2,166 | 00.1 | |

| Mendelssohn | 4 | 00.0 | 813 | 00.0 | |

| Sutton | 66 | 00.0 | 80,139 | 02.1 | |

| Moore | 2 | 00.0 | 750 | 00.0 | |

| Rhiannon | 1 | 00.0 | 250 | 00.0 | |

| Russell | 0 | 00.0 | 542 | 00.0 | |

| Total | 909,698 | 3,755,725 | |||

It will be seen that virtually all of Hutchins's surplus votes went to Faulkner, the second candidate on the Labor ticket, who was then elected. This is because all those voters who voted for the Labor party "above the line" had their second preferences automatically allocated to the second Labor candidate. All parties lodge a copy of their how-to-vote card with the Electoral Commission, and the commission follows this card in allocating the preferences of those who vote "above the line." If a voter wished to vote, for example, Hutchins 1 and Heffernan 2, they would need to vote "below the line" by numbering each of the 69 candidates.

In the third count, Heffernan's surplus was distributed and these votes elected Tierney. Faulkner's surplus was then distributed, but these were insufficient to elect Forshaw. Likewise, Tierney's surplus was insufficient to elect McDonald.

After this stage of the count, the remaining candidates in contention (that is, the leading candidates in the major party tickets) were in the following position:

| Candidate | Votes | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hutchins | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 1 |

| Faulkner | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 3 |

| Forshaw | 375,587 | 10.0 | |

| Oldfield | 360,263 | 09.6 | |

| Heffernan | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 2 |

| Tierney | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 4 |

| Macdonald | 300,313 | 08.0 | |

| Ridgeway | 273,109 | 07.3 | |

| Sutton | 80,186 | 02.1 | |

| (others) | 220,135 | 5.8 | |

| Total | 3,755,725 | ||

All the other candidates were then eliminated one by one, starting with the candidates with the smallest number of votes, and their votes were distributed among the candidates remaining in contention in accordance with the preferences expressed on their ballot papers. After this process was completed, the remaining candidates were in the following position:

| Candidate | Votes | % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hutchins | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 1 |

| Faulkner | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 3 |

| Forshaw | 450,446 | 12.0 | |

| Oldfield | 402,154 | 10.7 | |

| Heffernan | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 2 |

| Tierney | 536,533 | 14.3 | Elected 4 |

| Macdonald | 357,572 | 09.5 | |

| Ridgeway | 286,157 | 07.6 | |

| Sutton | 112,602 | 03.0 | |

| Total | 3,755,725 | ||

Sutton was then eliminated. 80% of Sutton's preferences went to Ridgeway, giving Ridgeway more votes than McDonald. McDonald was then eliminated, and 93% of his preferences went to Ridgeway, thus giving him a quota and the fifth Senate seat. Ridgeway's surplus was then distributed, and 96% of his votes went to Forshaw, thus giving him a quota and the sixth seat. Oldfield was the last remaining unsuccessful candidate. Provision for exhausted votes has been made in the current arrangements by providing that the last candidate does not require a quota, just a majority of the remaining votes. However it leaves the possibility that the election could fail, if the number of exhausted votes exceeded two quotas, making it impossible for the second last candidate to reach a quota. With above the line voting running at around 95%, this possibility is extremely remote.

A final point needs to be explained. It was noted above that when a candidate polls more votes than the quota, their surplus vote is distributed to other candidates. Thus, in the example given above, Hutchins's surplus was 909,698, or 1,446,231 (his primary vote) minus 536,533 (the quota). It may be asked: which 909,698 of Hutchins's 1,446,231 primary votes are distributed? Are they chosen at random from among his votes? In fact they are all distributed, but at less than their full value. Since 909,698 is 62.9% of 1,446,231, each of Hutchins's votes is transferred to other candidates as 62.9% of a vote: each vote is said to have a transfer value of 0.629. This avoids any possibility of an unrepresentative sample of his votes being transferred. After each count the candidate's progressive total is rounded down to the nearest whole number. This means that a small number of votes are lost by fractionation in the final count.

If at the end of the Senate count the two candidates remaining have an equal number of votes, the Australian Electoral Officer for the state shall select one at random.[83]

Senate casual vacancies

If a senator's seat becomes vacant mid-term, through disqualification, resignation, death or other cause, the legislature of the relevant state or territory chooses a replacement senator. A senator may resign by tendering their resignation to the President of the Senate or to the Governor-General, as required by section 19 of the constitution. A resignation is not effective until it is tendered in writing to the President or Governor-General.

Double dissolutions

Under the Australian Constitution, the House of Representatives and the Senate generally have equal legislative powers (the only exception being that appropriation (supply) bills must originate in the House of Representatives). This means that a government formed in the House of Representatives can be frustrated if a Senate majority rejects or delays passage of its legislative bills.

In such circumstances, Section 57 of the constitution empowers the Governor-General to dissolve both the House of Representatives and the Senate (termed a "double dissolution") and issue writs for an election in which every seat in Parliament is contested. The Governor-General would usually take such action only on the advice of the Prime Minister.

See also

- Elections in Australia

- Electoral systems of the Australian states and territories

References

- Scott Bennett and Rob Lundie, 'Australian Electoral Systems', Research Paper no. 5, 2007–08, Department of the Parliamentary Library, Canberra.

- "Enrol to vote". Australian Electoral Commission. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- "Joint Rolls Arrangement between Commonwealth, State and Territories". Electoral Council of Australia and New Zealand. Archived from the original on December 2021.

- VEC, The electoral roll

- Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) s 101

- Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) s 155

- "DOCUMENTS RELATING TO THE CALLING OF THE DOUBLE DISSOLUTION ELECTION FOR 2 JULY 2016" (PDF). Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. 8 May 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2016.

- "Candidates – Frequently Asked Questions". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- The Electoral Legislation Amendment (Modernisation and Other Measures) Act 2019, which came into effect on 1 March 2019.

- Candidates Handbook, p.6.

- "Commonwealth Electoral Act, s. 156". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Commonwealth Electoral Act, s. 158". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- "Australia's major electoral developments Timeline: 1900 – Present". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- Constitution of Australia, s. 28.

- Constitution of Australia, s. 32.

- Constitution of Australia, s. 6.

- "Commonwealth Electoral Act, s. 157". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Constitution of Australia, s. 13

- Constitution of Australia, s. 57.

- Lundie, Rob. "Australian elections timetable". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 8 January 2011.

- "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act – Section 28". Austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Scott Bennett, Compulsory voting in Australian national elections, Research Brief No. 6, 2005–06, Department of the Parliamentary Library, Canberra.

- "Electoral Offences". Voting within Australia – Frequently Asked Questions. Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- Independent Review of Local Government Elections: Issues Paper Archived 18 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- Australian Electoral Commission Site on Rules Governing Compulsory Voting in Federal and State Elections http://www.aec.gov.au/Voting/Compulsory_Voting.htm

- Australian Electoral Commission-Page 4 "Voter turnout–2016 House of Representatives and Senate elections"

- Victorian Electoral Commission: Unit 2: Voting rights and responsibilities Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Australian Electoral Commission: Compulsory voting in Australia

- "Compulsory Voting in Australia". Australian Electoral Commission. 16 January 2006. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ""The case for compulsory voting"; by Chris Puplick". Mind-trek.com. 30 June 1997. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Odgers, Australian Senate Practice". Aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 31 December 2004. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- "Ballot paper formality guidelines 2016" (PDF). Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Australian Electoral Commission, Electoral Pocketbook, Australian Electoral Commission, Canberra, June 2006, pp. 71–77. Retrieved September 2007.

- AustralianPolitics.com, Informal Voting in the House of Representatives 1983–2013. Retrieved July 2016.

- Hasham, Nicole (8 August 2016). "Election 2016: Voter turnout lowest since compulsory voting began in 1925". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- "Tasmanian political leaders face off in televised debate". ABC News. 27 February 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "Voting options". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Derek Chong, Sinclair Davidson, Tim Fry "It's an evil thing to oblige people to vote" Policy vol. 21 No. 4, Summer 2005–06

- "Blank vote legitimate, Latham asserts". Watoday.com.au. 16 August 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Burton-Bradley, Robert (16 August 2010). "Latham not breaking the law, says AEC". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010.

- Evans, Tim Compulsory voting in Australia at Australian Electoral Commission official website, June 2006. Accessed 15 June 2013

- Global Investment & Business Center (2013). Australia Country Study Guide: Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. ISBN 9781438773841.

- Adam Carr. "By-Elections 1917–19". Psephos Australian Election Archive. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- "Australia's major electoral developments". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- Lowrey, Tom (30 April 2022). "Federal election: Do preference deals matter? Who's making them? And how are they allocated?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- "Payment of Members Act 1870 (Vic)". Foundingdocs.gov.au. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Sawer, Marian; Norman Abjorensen; Philip Larkin (2009). Australia: The State of Democracy. Federation Press. pp. 107–114. ISBN 978-1862877252. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- Electronic voting and counting, Australian Capital Territory Electoral Commission

- "Preferential Voting". Australianpolitics.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "How the House of Representatives votes are counted". Australian Electoral Commission. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- "How does Australia's voting system work?". The Guardian. 14 August 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Voting Systems, Peak Body Proportional Representation Advocacy and Victorian Local Government" (PDF). Australian Political Studies Association.

- "Voters stung by back room deals between minor parties". news.com.au. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- "The Big Switch". Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- "Voting in the Senate". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Anderson, Stephanie (26 April 2016). "Senate voting changes explained in Australian Electoral Commission advertisements". ABC News. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "View News Headlines". Findlaw.com.au. 20 May 2005. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Information Centre for the 2007 Electoral Distribution, Where will you be in 2009?, p2.

- Green, Antony (6 March 2017). "The Growing Bias Against Perth and the South West in WA's Legislative Council". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Green, Antony (7 February 2013). "2013 WA Election Preview". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- "Voting HOR". Aec.gov.au. 31 July 2007. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Adam Carr. "By-Elections 1990–1993". Psephos Australian Election Archive. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- "Betts, K. – People and Place Vol. 4 No. 4". Elecpress.monash.edu.au. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "2004 Federal Election. Latest Seat Results. Election Results. Australian Broadcasting Corporation". ABC. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Counting the Votes". Aec.gov.au. 13 February 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- First Preferences by Group Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine at Australian Electoral Commission

- "Senate State First Preferences by Candidate". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- Colebatch, Tim Bringing a barnyard of crossbenchers to heel The Age, Melbourne, 10 September 2013

- Senate election reforms announced, including preferential voting above the line, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 22 February 2016

- Explainer: what changes to the Senate voting system are being proposed?, Stephen Morey, The Conversation, 23 February 2016

- "Electoral laws passed after marathon Parliament sitting". ABC News. Abc.net.au. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Antony Green (2 March 2016). "Senate Reform – Below the Line Optional Preferential Voting Included in Government's Legislation". Blogs.abc.net.au. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Antony Green (17 February 2016). "Would Electoral Reform Deliver the Coalition a Senate Majority at a Double Dissolution?". Blogs.abc.net.au. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Antony Green (23 September 2015). "The Origin of Senate Group Ticket Voting, and it didn't come from the Major Parties". Blogs.abc.net.au. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Antony Green (24 June 2015). "The Likely Political Consequences of Proposed Changes to the Senate's Electoral System". Blogs.abc.net.au. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Antony Green (10 June 2015). "By Accident Rather than Design – a Brief History of the Senate's Electoral System". Blogs.abc.net.au. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Antony Green. "All Senate reform articles". Blogs.abc.net.au. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "Lucy Gichuhi faces Senate dumping". SBS News.

- "Liberal senator Lucy Gichuhi relegated to unwinnable spot on SA preselection ticket". The Australian. 1 July 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Jane Norman (15 May 2018). "Lucy Gichuhi's political career facing abrupt end as Liberals fail to embrace newest member". ABC News (Australia).

- "Variants of the Gregory Fractional Transfer". Proportional Representation Society of Australia. 6 December 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- "Antony Green's Election Blog: Distortions in the Queensland Senate Count". Blogs.abc.net.au. 16 September 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) s 273

Further reading

- Brett, Judith (2019). From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia Got Compulsory Voting. Text Publishing Co. ISBN 9781925603842.

External links

| Library resources about Electoral system of Australia |