Alexander Dubček

Alexander Dubček (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈaleksander ˈduptʂek]; 27 November 1921 – 7 November 1992) was a Slovak politician who served as the First Secretary of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) (de facto leader of Czechoslovakia) from January 1968 to April 1969. He attempted to reform the communist government during the Prague Spring but was forced to resign following the Warsaw Pact invasion in August 1968.

Alexander Dubček | |

|---|---|

Alexander Dubček | |

| First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 5 January 1968 – 17 April 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Antonín Novotný |

| Succeeded by | Gustáv Husák |

| Chairman of the Federal Assembly of Czechoslovakia | |

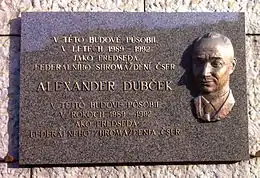

| In office 28 December 1989 – 25 June 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Alois Indra |

| Succeeded by | Michal Kováč |

| In office 28 April 1969 – 15 October 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Peter Colotka |

| Succeeded by | Dalibor Hanes |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 November 1921 Uhrovec, Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia) |

| Died | 7 November 1992 (aged 70) Prague, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic) [1] |

| Political party | Communist Party of Slovakia (1939–1948) Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (1948–1970) |

| Signature |  |

During his leadership under the slogan "Socialism with a human face", Czechoslovakia lifted censorship on the media and liberalized society, fueling the so-called New Wave in filmography and paving the way for a period that became known as the Prague Spring. However, Dubček was put under pressure by Stalinist voices inside the party, as well as the Soviet leadership, who opposed the direction the country was taking and feared that Czechoslovakia could loosen ties with the Soviet Union and become more westernized. As a result, the country was invaded by Soviet-led Warsaw Pact countries on 20–21 August 1968, effectively ending the Prague Spring. Dubček was forced to resign in April 1969 and succeeded by Gustáv Husák, who initiated normalization by clamping down on the liberalizing and pro-democracy movement. Dubček was expelled from the Communist Party in 1970.

During the Velvet Revolution in 1989, Dubček served as the Chairman of the federal Czechoslovak parliament and contended for the presidency with Václav Havel. The European Parliament awarded Dubček the Sakharov Prize the same year.[2]

Early life

Alexander Dubček was born in Uhrovec, Czechoslovakia (now in Slovakia), on 27 November 1921.[3][4] When he was three years old, the family moved to the Soviet Union, in part to help build socialism and in part because jobs were scarce in Czechoslovakia; so that he was raised until 12 on a commune in Pishpek (now Bishkek), in the Kirghiz SSR of the Soviet Union (now Kyrgyzstan), as a member of the Esperantist and Idist industrial cooperative Interhelpo.[5][6] In 1933, the family moved to Gorky, now Nizhny Novgorod, and in 1938 returned to Czechoslovakia.

During the Second World War, Dubček joined the underground resistance against the wartime pro-German Slovak state headed by Jozef Tiso. In August 1944, Dubček fought in the Jan Žižka partisan brigade[7] during the Slovak National Uprising and was wounded twice, while his brother, Július, was killed.[8]

Political career

During the war, Dubček joined the Communist Party of Slovakia (KSS),[9] which had been created after the formation of the Slovak state and in 1948 was transformed into the Slovak branch of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ).

After the war, he steadily rose through the ranks in Communist Czechoslovakia. From 1951 to 1955 he was a member of the National Assembly, the parliament of Czechoslovakia. In 1953, he was sent to the Moscow Political College, where he graduated in 1958.[10] In 1955, he joined the Central Committee of the Slovak branch and in 1962 became a member of the presidium. In 1958 he also joined the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which he served as a secretary from 1960 to 1962 and as a member of the presidium after 1962. From 1960 to 1968 he once more was a member of the federal parliament.

In 1963, a power struggle in the leadership of the Slovak branch unseated Karol Bacílek and Pavol David, hard-line allies of Antonín Novotný, First Secretary of the KSČ and President of Czechoslovakia. In their place, a new generation of Slovak Communists took control of party and state organs in Slovakia, led by Dubček, who became First Secretary of the Slovak branch of the party.[9]

Under Dubček's leadership, Slovakia began to evolve toward political liberalization. Because Novotný and his Stalinist predecessors had denigrated Slovak "bourgeois nationalists", most notably Gustáv Husák and Vladimír Clementis, in the 1950s, the Slovak branch worked to promote Slovak identity. This mainly took the form of celebrations and commemorations, such as the 150th birthdays of 19th century leaders of the Slovak National Revival Ľudovít Štúr and Jozef Miloslav Hurban, the centenary of the Matica slovenská in 1963, and the twentieth anniversary of the Slovak National Uprising. At the same time, the political and intellectual climate in Slovakia became freer than that in the Czech lands.[11] This was exemplified by the rising readership of Kultúrny život, the weekly newspaper of the Union of Slovak Writers, which published frank discussions of liberalization, federalization and democratization, written by the most progressive or controversial writers – both Slovak and Czech. Kultúrny život consequently became the first Slovak publication to gain a wide following among Czechs.

Prague Spring

The Czechoslovak planned economy in the 1960s was in serious decline and the imposition of central control from Prague disappointed local Communists, while the de-Stalinization program caused further disquiet. In October 1967, a number of reformers, most notably Ota Šik and Alexander Dubček, took action: they challenged First Secretary Antonín Novotný at a Central Committee meeting.[12] Novotný faced a mutiny in the Central Committee, so he secretly invited Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader, to make a whirlwind visit to Prague in December 1967 in order to shore up his own position. When Brezhnev arrived in Prague and met with the Central Committee members, he was stunned to learn of the extent of the opposition to Novotný, leading Brezhnev to opt for non-interference,[13] and paving the way for the Central Committee to force Novotný's resignation. Dubček, with his background and training in Russia, was seen by the USSR as a safe pair of hands. "Our Sasha", as Brezhnev called him,[14] became the new First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia on 5 January 1968.

The period following Novotný's downfall became known as the Prague Spring. During this time, Dubček and other reformers sought to liberalize the Communist government—creating "socialism with a human face".[15] Though this loosened the party's influence on the country, Dubček remained a devoted Communist and intended to preserve the party's rule. However, during the Prague Spring, he and other reform-minded Communists sought to win popular support for the Communist government by eliminating its most repressive features, allowing greater freedom of expression and tolerating political and social organizations not under Communist control.[16] "Dubček! Svoboda!"[17] became the popular refrain of student demonstrations during this period, while a poll gave him 78-percent public support.[18] Yet Dubček found himself in an increasingly untenable position. The program of reform gained momentum, leading to pressures for further liberalization and democratization. At the same time, hard-line Communists in Czechoslovakia and the leaders of other Warsaw Pact countries pressured Dubček to rein in the Prague Spring. Though Dubček wanted to rein in the reform movement, he refused to resort to any draconian measures to do so, while still stressing the leading role of the Party and the centrality of the Warsaw Pact.[19]

The Soviet leadership tried to slow down or stop the changes in Czechoslovakia through a series of negotiations. The Soviet Union agreed to bilateral talks with Czechoslovakia in July at Čierna nad Tisou, near the Slovak-Soviet border.[18] At the meeting, Dubček tried to reassure the Soviets and the Warsaw Pact leaders that he was still friendly to Moscow, arguing that the reforms were an internal matter. He thought he had learned an important lesson from the failing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, in which the leaders had gone as far as withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact. Dubček believed that the Kremlin would allow him a free hand in pursuing domestic reform as long as Czechoslovakia remained a faithful member of the Soviet bloc. Despite Dubček's continuing efforts to stress these commitments, Brezhnev and other Warsaw Pact leaders remained frightened, seeing even a partly free press as threatening an end to one-party rule in Czechoslovakia, and (by extension) elsewhere in Eastern Europe.[20]

Downfall

On the night of 20–21 August 1968, military forces from every Warsaw Pact member state (except for Albania, Romania and East Germany[21]) invaded Czechoslovakia. The occupying armies quickly seized control of Prague and the Central Committee's building, taking Dubček and other reformers into Soviet custody. But, before they were arrested, Dubček urged the people not to resist militarily, on the grounds that "presenting a military defense would have meant exposing the Czech and Slovak peoples to a senseless bloodbath".[22] Later in the day, Dubček and the others were taken to Moscow on a Soviet military transport aircraft.

The non-violent resistance of the Czech and Slovak population, which delayed total loss of control to the Warsaw Pact forces for a full eight months (in contrast to the Soviet military's estimate of four days), became a prime example of civilian-based defense. A latter-day The Good Soldier Švejk (referring to an early-20th-century Czech satirical novel) wrote of "the comradely pranks of changing street names and road signs, of pretending not to understand Russian, and of putting out a great variety of humorous welcoming posters".[23] Meanwhile, radio stations called for the invaders to return home: "Long live freedom, Svoboda, Dubček".[24] Nevertheless, the reformers were forced to accede to Soviet demands, signing the Moscow Protocol (which only František Kriegel refused to sign) and ending Dubček's Prague Spring.[25]

Dubček and most of the reformers were returned to Prague on 27 August, and Dubček retained his post as the party's first secretary until April 1969.[26] The achievements of the Prague Spring were not reversed immediately, but over a period of several months.

In January 1969, Dubček was hospitalized in Bratislava complaining of a cold and had to cancel a speech. Rumors sprang up that his illness was radiation sickness and that it was caused by radioactive strontium being placed in his soup during his stay in Moscow in an attempt to kill him. However, a U.S. intelligence report discounted this for lack of evidence.[27]

Dubček was forced to resign as First Secretary in April 1969, following the Czechoslovak Hockey Riots. He was re-elected to the Federal Assembly (as the federal parliament was now called) and became its chairman. He was later sent as ambassador to Turkey (1969–70),[28] allegedly in the hope that he would defect to the West, which however did not occur. In 1970, he was expelled from the Communist party and lost his seat in the Slovak parliament (which he had held continuously since 1964) and the Federal Assembly.

Private citizen

After his expulsion from the party, Dubček worked in the Forestry Service in Slovakia. He remained a popular figure among the Slovaks and Czechs he encountered on the job, using this reverence to procure scarce and hard-to-find materials for his workplace. Dubček and his wife, Anna, continued to live in a comfortable villa in a nice neighborhood in Bratislava. In 1988, Dubček was allowed to travel to Italy to accept an honorary doctorate from University of Bologna, and, while there, he gave an interview with Italian Communist Party daily newspaper L'Unità, his first public remarks to the press since 1970. Dubček's appearance and interview helped to return him to international prominence.

In 1989, he was awarded the annual Sakharov Prize in its second year of existence.[29]

Velvet Revolution

During the Velvet Revolution of 1989, he supported the Public Against Violence (VPN) and the Civic Forum. On the night of 24 November, Dubček appeared with Václav Havel on a balcony overlooking Wenceslas Square, where he was greeted with tremendous applause from the throngs of protesters below and embraced as a symbol of democratic freedom. Several onlookers even chanted, "Dubček na hrad!" ("Dubček to the Castle"—i.e., Dubček for President). He disappointed the crowd somewhat by calling the revolution a chance to continue the work he had started 20 years earlier to prune out what was wrong with Communism. By that time, the demonstrators in Prague wanted nothing to do with Communism of any sort, even Dubček's humane version. Later that night, Dubček was on stage with Havel at the Laterna Magika theatre, the headquarters of Civic Forum, when the entire leadership of the Communist Party resigned, in effect ending Communist rule in Czechoslovakia.[30]

Dubček was elected Chairman of the Federal Assembly (the Czechoslovak Parliament) on 28 December 1989, and re-elected in 1990 and 1992.

At the time of the dismantling of Communist party rule, Dubček described the Velvet Revolution as a victory for his humanistic socialist outlook. In 1990, he received the International Humanist Award from the International Humanist and Ethical Union. He also gave the commencement address to the graduates of the Class of 1990 at The American University in Washington, D.C.; it was his first trip to the United States.[31]

In 1992, he became leader of the Social Democratic Party of Slovakia and represented that party in the Federal Assembly. At that time, Dubček passively supported the union between Czechs and Slovaks in a single Czecho-Slovak federation against the ultimately successful push towards an independent Slovak state.

Death

Dubček died on 7 November 1992, as a result of injuries sustained in a car crash that took place on 1 September on the Czech D1 highway, near Humpolec, 20 days short of his 71st birthday.[32][33] He was buried in Slávičie údolie cemetery in Bratislava, Slovakia. His death remained a question of social and political theories alleging involvement by either then–Prime Minister of Slovakia Vladimír Mečiar or KGB. None of the theories were confirmed by subsequent investigation.[34][35]

Legacy and Cultural Representations

In 1984, French singer and songwriter Alice Dona had released a song named Le Jardinier de Bratislava with the lyrics written by Claude Lemesle, as an apolitical song about love and longing for freedom. The song was inspired by a trip of a French television crew to visit Dubček in his villa near Slavín, Bratislava. They were denied the access by the ŠtB secret police. The sole footage collected of Dubček was of him attending to his garden.[36]

References

- Battiata, Mary (8 November 1992). "Czech Leader Alexander Dubcek Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- European Parliament, Sakharov Prize Network, retrieved 10 September 2013

- "Alexander Dubček, Czechoslovak statesman". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Dennis Kavanagh (1998). "Dubcek, Alexander". A Dictionary of Political Biography. Oxford: OUP. p. 152. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- D. Viney, 'Alexander Dubcek', Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) pp. 17–19

- William Shawcross, 'Dubcek', (rev'd ed. 1990) p. 17

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (2016). A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. St. Martin's Press. p. 239. ISBN 9781250114754.

- D. Viney, 'Alexander Dubcek', Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) pp. 19–20

- B. Wasserstein, Barbarism & Civilization (Oxford 2007) p. 598

- D. Viney, 'Alexander Dubcek', Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) p. 21

- D. Viney, 'Alexander Dubcek', Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) pp. 23–4

- B. Wasserstein, Civilisation and Barbarism (Oxford 2007) p. 598

- D. Viney, "Alexander Dubcek", Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) p. 26

- Brezhnev, quoted in B. Wasserstein, Civilisation and Barbarism (Oxford 2007) pp. 598, 603

- B. Wasserstein, Civilisation and Barbarism (Oxford 2007) p. 600

- B. Wasserstein, Civilisation and Barbarism (Oxford 2007) p. 599

- Lost World of Communism (Czechoslovakia), BBC (Documentary)

- B. Wasserstein, Civilisation and Barbarism (Oxford 2007) p. 601

- D. Viney, 'Alexander Dubcek', Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) p. 31

- B. Wasserstein, Civilisation and Barbarism (Oxford 2007) p. 605

- "50 years on, what can we learn from the Prague Spring?". Independent.co.uk. 4 February 2021. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018.

- Quoted in B. Wasserstein, Civilisation and Barbarism (Oxford 2007) p. 605

- "Josef Schweik", Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) p. 332

- Documents, Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) p. 307

- Jenny Diski, The Sixties (London 2009) p. 82

- D. Viney, "Alexander Dubcek", Studies in Comparative Communism 1 (1968) pp. 36–7

- Radiation Sickness or Death Caused by Surreptitious Administration of Ionizing Radiation to an Individual Archived 3 September 2001 at the Wayback Machine. Report No. 4 of The Molecular Biology Working Group to The Biomedical Intelligence Subcommittee of The Scientific Intelligence Committee of USIB, 27 August 1969. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- B. Wasserstein, Civilisation and Barbarism (Oxford 2007) p. 606

- "Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought: List of prize winners", European Parliament webpage.

- Sebetsyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42532-5.

- "Commencement Address - C-SPAN Video Library". C-spanvideo.org. 13 May 1990. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- "Alexander Dubcek, 70, Dies in Prague" (The New York Times, 8 November 1992)

- Kopanic, Michael J Jr, "Case closed: Dubček's death declared an accident, not murder" Archived 10 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Central Europe Review (Vol 2, No 8), 28 February 2000.

- televize, Česká. "S Dubčekem umíralo i Československo. Čeští politici na pohřbu mlčeli". ČT24 - Nejdůvěryhodnější zpravodajský web v ČR - Česká televize (in Czech). Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "Záhadná smrt Alexandra Dubčeka: Jak to bylo ve skutečnosti?". EnigmaPlus.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "Ako Dubček inšpiroval francúzsku speváčku". Pravda.sk (in Slovak). 1 December 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

External links

- Works by or about Alexander Dubček in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Alexander Dubček profile on the Sakharov Prize Network

- Dubcek: Dubcek and Czechoslovakia 1918–1968 by William Shawcross (1970)

- Hope Dies Last The Autobiography of Alexander Dubcek by Alexander Dubcek (Author), Jiří Hochman (Editor, Translator), Kodansha Europe (1993), ISBN 1-56836-000-2.