History of Italy

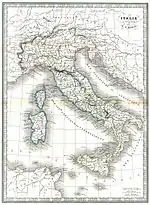

The history of Italy covers the ancient period, the Middle Ages, and the modern era. Since classical antiquity, ancient Etruscans, various Italic peoples (such as the Latins, Samnites, and Umbri), Celts, Magna Graecia colonists, and other ancient peoples have inhabited the Italian Peninsula.[1][2] In antiquity, Italy was the homeland of the Romans and the metropole of the Roman Empire's provinces.[3][4] Rome was founded as a Kingdom in 753 BC and became a republic in 509 BC, when the Roman monarchy was overthrown in favor of a government of the Senate and the People. The Roman Republic then unified Italy at the expense of the Etruscans, Celts, and Greek colonists of the peninsula. Rome led Socii, a confederation of the Italic peoples, and later with the rise of Rome dominated Western Europe, Northern Africa, and the Near East.

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

Timeline |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Mythology and Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

|

The Roman Republic saw its fall after the assassination of Julius Caesar. The Roman Empire later dominated Western Europe and the Mediterranean for many centuries, making immeasurable contributions to the development of Western philosophy, science and art. After the fall of Rome in AD 476, Italy was fragmented in numerous city-states and regional polities; despite seeing famous personalities from its territory and closely related ones (such as Dante Alighieri, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Niccolò Machiavelli, Galileo Galilei, and Napoleon Bonaparte) rise, it remained politically divided to a large extent. The maritime republics, in particular Venice and Genoa, rose to great prosperity through shipping, commerce, and banking, acting as Europe's main port of entry for Asian and Near Eastern imported goods and laying the groundwork for capitalism.[5][6] Central Italy remained under the Papal States, while Southern Italy remained largely feudal due to a succession of Byzantine, Arab, Norman, Spanish, and Bourbon crowns.[7] The Italian Renaissance spread to the rest of Europe, bringing a renewed interest in humanism, science, exploration, and art with the start of the modern era.[8] Italian explorers (including Marco Polo, Christopher Columbus, and Amerigo Vespucci) discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, helping to usher in the Age of Discovery,[9][10] although the Italian states had no occasions to found colonial empires outside of the Mediterranean Basin.

By the mid-19th century, the Italian unification by Giuseppe Garibaldi, backed by the Kingdom of Sardinia, led to the establishment of an Italian nation-state. The new Kingdom of Italy, established in 1861, quickly modernized and built a colonial empire, controlling parts of Africa, and countries along the Mediterranean. At the same time, Southern Italy remained rural and poor, originating the Italian diaspora. In World War I, Italy completed the unification by acquiring Trento and Trieste, and gained a permanent seat in the League of Nations's executive council. Italian nationalists considered World War I a mutilated victory because Italy did not have all the territories promised by the Treaty of London (1915) and that sentiment led to the rise of the Fascist dictatorship of Benito Mussolini in 1922. The subsequent participation in World War II with the Axis powers, together with Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan, ended in military defeat, Mussolini's arrest and escape (aided by the German dictator Adolf Hitler), and the Italian Civil War between the Italian Resistance (aided by the Kingdom, now a co-belligerent of the Allies) and a Nazi-fascist puppet state known as the Italian Social Republic.

Following the liberation of Italy, the fall of the Social Republic, and the killing of Mussolini at the hands of the Resistance, the 1946 Italian constitutional referendum abolished the monarchy and became a republic, reinstated democracy, enjoyed an economic miracle, and founded the European Union (Treaty of Rome), NATO, and the Group of Six (later G7 and G20). It remains a strong economic, cultural, military, and political factor in the 21st century.[11][12]

Prehistory

_-_R_1_-_Area_di_Zurla_-_Nadro_(ph_Luca_Giarelli).jpg.webp)

The arrival of the first hominins was 850,000 years ago at Monte Poggiolo.[13] The presence of the Homo neanderthalensis has been demonstrated in archaeological findings near Rome and Verona dating to c. 50,000 years ago (late Pleistocene). Homo sapiens sapiens appeared during the upper Palaeolithic: the earliest sites in Italy dated 48,000 years ago is Riparo Mochi (Italy).[14] In November 2011 tests conducted at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit in England on what were previously thought to be Neanderthal baby teeth, which had been unearthed in 1964 dating from between 43,000 and 45,000 years ago.[15] Remains of the later prehistoric age have been found in Lombardy (stone carvings in Valcamonica) and in Sardinia (nuraghe). The most famous is perhaps that of Ötzi the Iceman, the mummy of a mountain hunter found in the Similaun glacier in South Tyrol, dating to c. 3400–3100 BC (Copper Age).

During the Copper Age, Indoeuropean people migrated to Italy. Approximately four waves of population from north to the Alps have been identified. A first Indoeuropean migration occurred around the mid-3rd millennium BC, from a population who imported coppersmithing.[17] The Remedello culture took over the Po Valley. The second wave of immigration occurred in the Bronze Age, from the late 3rd to the early 2nd millennium BC, with tribes identified with the Beaker culture and by the use of bronze smithing, in the Padan Plain, in Tuscany and on the coasts of Sardinia and Sicily.[18]

In the mid-2nd millennium BC, a third wave arrived, associated with the Apenninian civilization and the Terramare culture which takes its name from the black earth (terremare) residue of settlement mounds, which have long served the fertilizing needs of local farmers.[19][20] The occupations of the Terramare people as compared with their Neolithic predecessors may be inferred with comparative certainty. They were still hunters, but had domesticated animals; they were fairly skilful metallurgists, casting bronze in moulds of stone and clay, and they were also agriculturists, cultivating beans, the vine, wheat and flax.[21]

In the late Bronze Age, from the late 2nd millennium to the early 1st millennium BC, a fourth wave, the Proto-Villanovan culture, related to the Central European Urnfield culture, brought iron-working to the Italian peninsula. Proto-Villanovan culture was part of the central European Urnfield culture system. Similarity has also been noted with the regional groups of Bavaria-Upper Austria[22] and of the middle-Danube.[22][23] Another hypothesis, however, is that it was a derivation from the previous Terramare culture of the Po Valley.[24][25] Various authors, such as Marija Gimbutas, associated this culture with the arrival, or the spread, of the proto-Italics into the Italian peninsula.[22]In Sicily, small dolmens dating back to the end of the third millennium BC have recently been found, similar to those found in Sardinia, the Balearic Islands and Spain. Various scholars associate this culture (so called in Sicily "Dolmens Culture") with the arrival on the west coast of Sicily, of a cultural wave bringing the bell-shaped goblet coming from the Sardinian coast.[26]

Nuragic civilization

Born in Sardinia and southern Corsica, the Nuraghe civilization lasted from the early Bronze Age (18th century BC) to the 2nd century AD, when the islands were already Romanized.[27][28][29][30] They take their name from the characteristic Nuragic towers, which evolved from the pre-existing megalithic culture, which built dolmens and menhirs.[31] Today more than 7,000 nuraghes[32] dot the Sardinian landscape.

No written records of this civilization have been discovered,[33] apart from a few possible short epigraphic documents belonging to the last stages of the Nuragic civilization.[34] The only written information there comes from classical literature of the Greeks and Romans, and may be considered more mythological than historical.[35]

The language (or languages) spoken in Sardinia during the Bronze Age is (are) unknown since there are no written records from the period, although recent research suggests that around the 8th century BC, in the Iron Age, the Nuragic populations may have adopted an alphabet similar to that used in Euboea.[36]

According to Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, the Paleo-Sardinian language was akin to Proto-Basque and ancient Iberian with faint Indo-European traces,[37] but others believe it was related to Etruscan. Some scholars theorize that there were actually various linguistic areas (two or more) in Nuragic Sardinia, possibly Pre-Indo-Europeans and Indo-Europeans.[34]: 241–254

Iron Age

Italy gradually enters the proto-historical period in the 8th century BC, with the introduction of the Phoenician script and its adaptation in various regional variants.

Etruscan civilization

The Etruscan civilization flourished in central Italy after 800 BC. The origins of the Etruscans are lost in prehistory. The main hypotheses are that they are indigenous, probably stemming from the Villanovan culture. A mitochondrial DNA study of 2013 has suggested that the Etruscans were probably an indigenous population.[38]

It is widely accepted that Etruscans spoke a non-Indo-European language. Some inscriptions in a similar language have been found on the Aegean island of Lemnos. Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized pairing. The historical Etruscans had achieved a form of state with remnants of chiefdom and tribal forms. The Etruscan religion was an immanent polytheism, in which all visible phenomena were considered to be a manifestation of divine power, and deities continually acted in the world of men and could, by human action or inaction, be dissuaded against or persuaded in favor of human affairs.

Etruscan expansion was focused across the Apennines. Some small towns in the 6th century BC have disappeared during this time, ostensibly consumed by greater, more powerful neighbors. However, there exists no doubt that the political structure of the Etruscan culture was similar, albeit more aristocratic, to Magna Graecia in the south. The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian peninsula and the western Mediterranean sea. Here their interests collided with those of the Greeks, especially in the 6th century BC, when Phoceans of Italy founded colonies along the coast of France, Catalonia and Corsica. This led the Etruscans to ally themselves with the Carthaginians, whose interests also collided with the Greeks.[39][40]

Around 540 BC, the Battle of Alalia led to a new distribution of power in the western Mediterranean Sea. Although the battle had no clear winner, Carthage managed to expand its sphere of influence at the expense of the Greeks, and Etruria saw itself relegated to the northern Tyrrhenian Sea with full ownership of Corsica. From the first half of the 5th century, the new international political situation meant the beginning of the Etruscan decline after losing their southern provinces. In 480 BC, Etruria's ally Carthage was defeated by a coalition of Magna Graecia cities led by Syracuse.[39][40]

A few years later, in 474 BC, Syracuse's tyrant Hiero defeated the Etruscans at the Battle of Cumae. Etruria's influence over the cities of Latium and Campania weakened, and it was taken over by Romans and Samnites. In the 4th century, Etruria saw a Gallic invasion end its influence over the Po valley and the Adriatic coast. Meanwhile, Rome had started annexing Etruscan cities. This led to the loss of their north provinces. Etruscia was assimilated by Rome around 500 BC.[39][40]

Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family. Among the Italic peoples in the Italian peninsula were the Osci, the Veneti, the Samnites, the Latins and the Umbri.[41]

In the region south of the Tiber (Latium Vetus), the Latial culture of the Latins emerged, while in the north-east of the peninsula the Este culture of the Veneti appeared. Roughly in the same period, from their core area in central Italy (modern-day Umbria and Sabina region), the Osco-Umbrians began to emigrate in various waves, through the process of Ver sacrum, the ritualized extension of colonies, in southern Latium, Molise and the whole southern half of the peninsula, replacing the previous tribes, such as the Opici and the Oenotrians. This corresponds with the emergence of the Terni culture, which had strong similarities with the Celtic cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène. The Umbrian necropolis of Terni, which dates back to the 10th century BCE, was identical in every aspect to the Celtic necropolis of the Golasecca culture.[42]

Before and during the period of the arrival of the Greek and Phoenician immigrants, the island of Sicily was already inhabited by native Italics, which are divided into 3 major groups, the Elymians in the west, the Sicani in the centre, and the Sicels in the east. The Sicels gave Sicily the name it has held since antiquity.[43]

Among the populations who inhabited northern Italy in the Iron Age, one of the most prominent were the Ligures. It is generally believed that around 2000 BC, they occupied a large area of the Italian peninsula, including much of north-western Italy and all of northern Tuscany (the part that lies north of the Arno river). Since many scholars consider the language of this ancient population to be Pre-Indo-European, they are often not classified as Italics.[44]

By the mid-first millennium BCE, the Latins of Rome were growing in power and influence. After the Latins had liberated themselves from Etruscan rule they acquired a dominant position among the Italic tribes. Frequent conflict between various Italic tribes followed. The best documented of these are the wars between the Latins and the Samnites.[45]

The Latins eventually succeeded in unifying the Italic elements in the country. Many non-Latin Italic tribes adopted Latin culture and acquired Roman citizenship. In the early first century BCE, several Italic tribes, in particular the Marsi and the Samnites, rebelled against Roman rule. This conflict is called the Social War. After Roman victory was secured, all peoples in Italy, except for the Celts of the Po Valley, were granted Roman citizenship. In the subsequent centuries, Italic tribes adopted Latin language and culture in a process known as Romanization.[45]

Magna Graecia

In the eighth and seventh centuries BC, for various reasons, including demographic crisis (famine, overcrowding, etc.), the search for new commercial outlets and ports, and expulsion from their homeland, Greeks began to settle in Southern Italy (Cerchiai, pp. 14–18). Also during this period, Greek colonies were established in places as widely separated as the eastern coast of the Black Sea, Eastern Libya and Massalia (Marseille) in Gaul. They included settlements in Sicily and the southern part of the Italian peninsula.

The Romans called the area of Sicily and the foot of Italy Magna Graecia (Latin, "Great Greece"), since it was densely inhabited by the Greeks. The ancient geographers differed on whether the term included Sicily or merely Apulia, Campania and Calabria—Strabo being the most prominent advocate of the wider definitions.

With this colonization, Greek culture was exported to Italy, in its dialects of the Ancient Greek language, its religious rites and its traditions of the independent polis. An original Hellenic civilization soon developed, later interacting with the native Italic and Latin civilisations. The most important cultural transplant was the Chalcidean/Cumaean variety of the Greek alphabet, which was adopted by the Etruscans; the Old Italic alphabet subsequently evolved into the Latin alphabet, which became the most widely used alphabet in the world.

_18.JPG.webp)

Many of the new Hellenic cities became very rich and powerful, like Neapolis (Νεάπολις, Naples, "New City"), Syracuse, Acragas, and Sybaris (Σύβαρις). Other cities in Magna Graecia included Tarentum (Τάρας), Epizephyrian Locri (Λοκροί Ἐπιζεφύριοι), Rhegium (Ῥήγιον), Croton (Κρότων), Thurii (Θούριοι), Elea (Ἐλέα), Nola (Νῶλα), Ancona (Ἀγκών), Syessa (Σύεσσα), Bari (Βάριον), and others.

After Pyrrhus of Epirus failed in his attempt to stop the spread of Roman hegemony in 282 BC, the south fell under Roman domination and remained in such a position well into the barbarian invasions (the Gladiator War is a notable suspension of imperial control). It was held by the Byzantine Empire after the fall of Rome in the West and even the Lombards failed to consolidate it, though the centre of the south was theirs from Zotto's conquest in the final quarter of the 6th century.

Roman period

Roman Kingdom

Little is certain about the history of the Roman Kingdom, as nearly no written records from that time survive, and the histories about it that were written during the Republic and Empire are largely based on legends. However, the history of the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding, traditionally dated to 753 BC with settlements around the Palatine Hill along the river Tiber in Central Italy, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic in about 509 BC.

The site of Rome had a ford where the Tiber could be crossed. The Palatine Hill and hills surrounding it presented easily defensible positions in the wide fertile plain surrounding them. All of these features contributed to the success of the city.

The traditional account of Roman history, which has come down to us through Livy, Plutarch, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and others, is that in Rome's first centuries it was ruled by a succession of seven kings. The traditional chronology, as codified by Varro, allots 243 years for their reigns, an average of almost 35 years, which, since the work of Barthold Georg Niebuhr, has been generally discounted by modern scholarship.

The Gauls destroyed much of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the Battle of the Allia in 390 BC (Varronian, according to Polybius the battle occurred in 387/6) and what was left was eventually lost to time or theft. With no contemporary records of the kingdom existing, all accounts of the kings must be carefully questioned.[47]

According to the founding myth of Rome, the city was founded on 21 April 753 BC by twin brothers Romulus and Remus, who descended from the Trojan prince Aeneas[48] and who were grandsons of the Latin King, Numitor of Alba Longa.

Roman Republic

According to tradition and later writers such as Livy, the Roman Republic was established around 509 BC,[49] when the last of the seven kings of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, was deposed by Lucius Junius Brutus, and a system based on annually elected magistrates and various representative assemblies was established.[50] A constitution set a series of checks and balances, and a separation of powers. The most important magistrates were the two consuls, who together exercised executive authority as imperium, or military command.[51] The consuls had to work with the senate, which was initially an advisory council of the ranking nobility, or patricians, but grew in size and power.[52]

In the 4th century BC the Republic came under attack by the Gauls, who initially prevailed and sacked Rome. The Romans then took up arms and drove the Gauls back, led by Camillus. The Romans gradually subdued the other peoples on the Italian peninsula, including the Etruscans.[53] The last threat to Roman hegemony in Italy came when Tarentum, a major Greek colony, enlisted the aid of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 281 BC, but this effort failed as well.[54][55]

In the 3rd century BC Rome had to face a new and formidable opponent: the powerful Phoenician city-state of Carthage. In the three Punic Wars, Carthage was eventually destroyed and Rome gained control over Hispania, Sicily and North Africa. After defeating the Macedonian and Seleucid Empires in the 2nd century BC, the Romans became the dominant people of the Mediterranean Sea.[56][57] The conquest of the Hellenistic kingdoms provoked a fusion between Roman and Greek cultures and the Roman elite, once rural, became a luxurious and cosmopolitan one. By this time Rome was a consolidated empire – in the military view – and had no major enemies.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The one open sore was Spain (Hispania). Roman armies occupied Spain in the early 2nd century BC but encountered stiff resistance from that time down to the age of Augustus. The Celtiberian stronghold of Numantia became the centre of Spanish resistance to Rome in the 140s and 130s BC.[58] Numantia fell and was completely razed to the ground in 133 BC. In 105 BC, the Celtiberians still retained enough of their native vigour and ferocity to drive the Cimbri and Teutones from northern Spain,[59] though these had crushed Roman arms in southern Gaul, inflicting 80,000 casualties on the Roman army which opposed them. The conquest of Hispania was completed in 19 BC—but at a heavy cost and severe losses.[60]

Towards the end of the 2nd century BC, a huge migration of Germanic tribes took place, led by the Cimbri and the Teutones. These tribes overwhelmed the peoples with whom they came into contact and posed a real threat to Italy itself. At the Battle of Aquae Sextiae and the Battle of Vercellae the Germans were virtually annihilated, which ended the threat. In these two battles the Teutones and Ambrones are said to have lost 290,000 men (200,000 killed and 90,000 captured); and the Cimbri 220,000 men (160,000 killed, and 60,000 captured).[61]

In the mid-1st century BC, the Republic faced a period of political crisis and social unrest. Into this turbulent scenario emerged the figure of Julius Caesar. Caesar reconciled the two more powerful men in Rome: Marcus Licinius Crassus, his sponsor, and Crassus' rival, Pompey. The First Triumvirate ("three men"), had satisfied the interests of these three men: Crassus, the richest man in Rome, became richer; Pompey exerted more influence in the Senate; and Caesar held consulship and military command in Gaul.[62]

In 53 BC, the Triumvirate disintegrated at Crassus' death. Crassus had acted as mediator between Caesar and Pompey, and, without him, the two generals began to fight for power. After being victorious in the Gallic Wars and earning respect and praise from the legions, Caesar was a clear menace to Pompey, that tried to legally remove Caesar's legions. To avoid this, Caesar crossed the Rubicon River and invaded Rome in 49 BC, rapidly defeating Pompey. With his sole preeminence over Rome, Caesar gradually accumulated many offices, eventually being granted a dictatorship for perpetuity. He was murdered in 44 BC, in the Ides of March by the Liberatores.[63] Caesar's assassination caused political and social turmoil in Rome; without the dictator's leadership, the city was ruled by his friend and colleague, Mark Antony. Octavius (Caesar's adopted son), along with general Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Caesar's best friend,[64] established the Second Triumvirate. Lepidus was forced to retire in 36 BC after betraying Octavian in Sicily. Antony settled in Egypt with his lover, Cleopatra VII. Mark Antony's affair with Cleopatra was seen as an act of treason since she was the queen of a foreign power and Antony was adopting an extravagant and Hellenistic lifestyle that was considered inappropriate for a Roman statesman.[65]

Following Antony's Donations of Alexandria, which gave to Cleopatra the title of "Queen of Kings", and to their children the regal titles to the newly conquered Eastern territories, the war between Octavian and Mark Antony broke out. Octavian annihilated Egyptian forces in the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. Mark Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide, leaving Octavianus the sole ruler of the Republic.

After the Battle of Actium, the period of major naval battles was over and the Romans possessed unchallenged naval supremacy in the North Sea, Atlantic coasts, Mediterranean, Red Sea, and the Black Sea until the emergence of new naval threats in the form of the Franks and the Saxons in the North Sea, and in the form of Borani, Herules and Goths in the Black Sea.

Roman Empire

In 27 BC, Octavian was the sole Roman leader. His leadership brought the zenith of the Roman civilization, that lasted for four decades. In that year, he took the name Augustus. That event is usually taken by historians as the beginning of Roman Empire. Officially, the government was republican, but Augustus assumed absolute powers.[66][67] The Senate granted Octavian a unique grade of Proconsular imperium, which gave him authority over all Proconsuls (military governors).[68]

The unruly provinces at the borders, where the vast majority of the legions were stationed, were under the control of Augustus. These provinces were classified as imperial provinces. The peaceful senatorial provinces were under the control of the Senate. The Roman legions, which had reached an unprecedented number (around 50) because of the civil wars, were reduced to 28.

As provinces were being established throughout the Mediterranean, Roman Italy maintained a special status which made it Domina Provinciarum ("ruler of the provinces", the latter being all the remaining territories outside Italy),[69][70][71] and - especially in relation to the first centuries of imperial stability - Rectrix Mundi ("governor of the world")[72][73] and Omnium Terrarum Parens ("parent of all lands").[74][75] Such a status meant that, within Italy in times of peace, Roman magistrates exercised the Imperium domi (police power) as an alternative to the Imperium militiae (military power). Italy's inhabitants had Latin Rights as well as religious and financial privileges.

Under Augustus's rule, Roman literature grew steadily in the Golden Age of Latin Literature. Poets like Vergil, Horace, Ovid and Rufus developed a rich literature, and were close friends of Augustus. Along with Maecenas, he stimulated patriotic poems, as Vergil's epic Aeneid and also historiographical works, like those of Livy. The works of this literary age lasted through Roman times, and are classics. Augustus also continued the shifts on the calendar promoted by Caesar, and the month of August is named after him.[76] Augustus' enlightened rule resulted in a 200 years long peaceful and thriving era for the Empire, known as Pax Romana.[77]

Despite its military strength, the Empire made few efforts to expand its already vast extent; the most notable being the conquest of Britain, begun by emperor Claudius (47), and emperor Trajan's conquest of Dacia (101–102, 105–106). In the 1st and 2nd century, Roman legions were also employed in intermittent warfare with the Germanic tribes to the north and the Parthian Empire to the east. Meanwhile, armed insurrections (e.g. the Hebraic insurrection in Judea) (70) and brief civil wars (e.g. in 68 AD the year of the four emperors) demanded the legions' attention on several occasions. The seventy years of Jewish–Roman wars in the second half of the 1st century and the first half of the 2nd century were exceptional in their duration and violence.[78] An estimated 1,356,460 Jews were killed as a result of the First Jewish Revolt;[79] the Second Jewish Revolt (115–117) led to the death of more than 200,000 Jews;[80] and the Third Jewish Revolt (132–136) resulted in the death of 580,000 Jewish soldiers.[81] The Jewish people never recovered until the creation of the state of Israel in 1948.[82]

After the death of Emperor Theodosius I (395), the Empire was divided into an Eastern and a Western Roman Empire. The Western part faced increasing economic and political crisis and frequent barbarian invasions, so the capital was moved from Mediolanum to Ravenna. In 476, the last Western Emperor Romulus Augustulus was deposed by Odoacer; for a few years Italy stayed united under the rule of Odoacer, only to be overthrown by the Ostrogoths, who in turn were overthrown by Roman emperor Justinian. Not long after the Lombards invaded the peninsula, and Italy did not reunite under a single ruler until thirteen centuries later.

Middle Ages

Odoacer's rule came to an end when the Ostrogoths, under the leadership of Theodoric, conquered Italy. Decades later, the armies of Eastern Emperor Justinian entered Italy with the goal of re-establishing imperial Roman rule, which led to the Gothic War that devastated the whole country with famine and epidemics. This ultimately allowed another Germanic tribe, the Lombards, to take control over vast regions of Italy. In 751 the Lombards seized Ravenna, ending Byzantine rule in northern Italy. Facing a new Lombard offensive, the Papacy appealed to the Franks for aid.[83]

In 756 Frankish forces defeated the Lombards and gave the Papacy legal authority over much of central Italy, thus establishing the Papal States. In 800, Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by the Pope in Saint Peter's Basilica. After the death of Charlemagne (814), the new empire soon disintegrated under his weak successors. There was a power vacuum in Italy as a result of this. This coincided with the rise of Islam in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa and the Middle East. In the South, there were attacks from the Umayyad Caliphate and the Abbasid Caliphate. In the North, there was a rising power of communes. In 852, the Saracens took Bari and founded an emirate there. Islamic rule over Sicily was effective from 902, and the complete rule of the island lasted from 965 until 1061. The turn of the millennium brought about a period of renewed autonomy in Italian history. In the 11th century, trade slowly recovered as the cities started to grow again. The Papacy regained its authority and undertook a long struggle against the Holy Roman Empire.

The Investiture controversy, a conflict over two radically different views of whether secular authorities such as kings, counts, or dukes, had any legitimate role in appointments to ecclesiastical offices such as bishoprics, was finally resolved by the Concordat of Worms in 1122, although problems continued in many areas of Europe until the end of the medieval era. In the north, a Lombard League of communes launched a successful effort to win autonomy from the Holy Roman Empire, defeating Emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the Battle of Legnano in 1176. In the south, the Normans occupied the Lombard and Byzantine possessions, ending the six-century-old presence of both powers in the peninsula.[84]

The few independent city-states were also subdued. During the same period, the Normans also ended Muslim rule in Sicily. In 1130, Roger II of Sicily began his rule of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Roger II was the first King of Sicily and had succeeded in uniting all the Norman conquests in Southern Italy into one kingdom with a strong centralized government. In 1155, Emperor Manuel Komnenos attempted to regain Southern Italy from the Normans, but the attempt failed and in 1158 the Byzantines left Italy. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily lasted until 1194 when Sicily was claimed by the German Hohenstaufen Dynasty. The Kingdom of Sicily would last under various dynasties until the 19th century.

Right: Trade routes and colonies of the Genoese (red) and Venetian (green) empires.

Between the 12th and 13th centuries, Italy developed a peculiar political pattern, significantly different from feudal Europe north of the Alps. As no dominant powers emerged as they did in other parts of Europe, the oligarchic city-state became the prevalent form of government. Keeping both direct Church control and Imperial power at arm's length, the many independent city states prospered through commerce, based on early capitalist principles ultimately creating the conditions for the artistic and intellectual changes produced by the Renaissance.[85]

Italian towns had appeared to have exited from Feudalism so that their society was based on merchants and commerce.[86] Even northern cities and states were also notable for their merchant republics, especially the Republic of Venice.[87] Compared to feudal and absolute monarchies, the Italian independent communes and merchant republics enjoyed relative political freedom that boosted scientific and artistic advancement.[88]

During this period, many Italian cities developed republican forms of government, such as the republics of Florence, Lucca, Genoa, Venice and Siena. During the 13th and 14th centuries these cities grew to become major financial and commercial centers at European level.[89]

Thanks to their favourable position between East and West, Italian cities such as Venice became international trading and banking hubs and intellectual crossroads. Milan, Florence and Venice, as well as several other Italian city-states, played a crucial innovative role in financial development, devising the main instruments and practices of banking and the emergence of new forms of social and economic organization.[88]

During the same period, Italy saw the rise of the Maritime Republics: Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Amalfi, Ragusa, Ancona, Gaeta and the little Noli.[90] From the 10th to the 13th centuries these cities built fleets of ships both for their own protection and to support extensive trade networks across the Mediterranean, leading to an essential role in the Crusades. The maritime republics, especially Venice and Genoa, soon became Europe's main gateways to trade with the East, establishing colonies as far as the Black Sea and often controlling most of the trade with the Byzantine Empire and the Islamic Mediterranean world. The county of Savoy expanded its territory into the peninsula in the late Middle Ages, while Florence developed into a highly organized commercial and financial city-state, becoming for many centuries the European capital of silk, wool, banking and jewellery.

Renaissance

Italy was the main center of the Renaissance, whose flourishing of the arts, architecture, literature, science, historiography, and political theory influenced all of Europe.[91][92]

By the late Middle Ages, central and southern Italy, once the heartland of the Roman Empire and Magna Graecia respectively, was far poorer than the north. Rome was a city largely in ruins, and the Papal States were a loosely administered region with little law and order. Partly because of this, the Papacy had relocated to Avignon in France. Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia had for some time been under foreign domination. The Italian trade routes that covered the Mediterranean and beyond were major conduits of culture and knowledge. The city-states of Italy expanded greatly during this period and grew in power to become de facto fully independent of the Holy Roman Empire.[93]

The Black Death in 1348 inflicted a terrible blow to Italy, killing perhaps one third of the population.[94] The recovery from the demographic and economic disaster led to a resurgence of cities, trade and economy which greatly stimulated the successive phase of the Humanism and Renaissance (15th–16th centuries) when Italy again returned to be the center of Western civilization, strongly influencing the other European countries with Courts like Este in Ferrara and Medici in Florence.

.jpg.webp)

The Renaissance was so called because it was a "rebirth" not only of economy and urbanization, but also of arts and science. It has been argued that this cultural rebirth was fuelled by massive rediscoveries of ancient texts that had been forgotten for centuries by Western civilization, hidden in monastic libraries or in the Islamic world, as well as the translations of Greek and Arabic texts into Latin. The migration west into Italy of intellectuals fleeing the crumbling Eastern Roman Empire at this time also played a significant part.

The Italian Renaissance began in Tuscany, centered in the city of Florence. It then spread south, having an especially significant impact on Rome, which was largely rebuilt by the Renaissance popes. The Italian Renaissance peaked in the 16th century. The Renaissance ideals first spread from Florence to the neighbouring states of Tuscany such as Siena and Lucca. Tuscan architecture and painting soon became a model for all the city-states of northern and central Italy, as the Tuscan variety of Italian language came to predominate throughout the region, especially in literature.

Literature, philosophy, and science

Accounts of Renaissance literature usually begin with Petrarch (best known for the elegantly polished vernacular sonnet sequence of Il Canzoniere and for the book collecting that he initiated) and his friend and contemporary Giovanni Boccaccio (author of The Decameron). Famous vernacular poets of the 15th century include the Renaissance epic authors Luigi Pulci (Morgante), Matteo Maria Boiardo (Orlando Innamorato), and Ludovico Ariosto (Orlando Furioso).

Renaissance scholars such as Niccolò de' Niccoli and Poggio Bracciolini scoured the libraries in search of works by such classical authors as Plato, Cicero and Vitruvius. The works of ancient Greek and Hellenistic writers (such as Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, and Ptolemy) and Muslim scientists were imported into the Christian world, providing new intellectual material for European scholars. 15th-century writers such as the poet Poliziano and the Platonist philosopher Marsilio Ficino made extensive translations from both Latin and Greek. Other Greek scholars of the period were two monks from the monastery of Seminara in Calabria. They were Barlaam of Seminara and his disciple Leonzio Pilato of Seminara. Barlaam was a master in Greek and was the initial teacher to Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio of the language. Leonzio Pilato made an almost word for word translation of Homer's works into Latin for Giovanni Boccaccio.[97][98][99]

In the early 16th century, Baldassare Castiglione with The Book of the Courtier laid out his vision of the ideal gentleman and lady, while Niccolò Machiavelli in The Prince, laid down the foundation of modern philosophy, especially modern political philosophy, in which the effective truth is taken to be more important than any abstract ideal. It was also in direct conflict with the dominant Catholic and scholastic doctrines of the time concerning how to consider politics and ethics.[100][101]

Architecture, sculpture, and painting

Italian Renaissance painting exercised a dominant influence on subsequent European painting (see Western painting) for centuries afterwards, with artists such as Giotto di Bondone, Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Michelangelo, Raphael, Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, and Titian.

The same is true for architecture, as practiced by Brunelleschi, Leone Alberti, Andrea Palladio, and Bramante. Their works include Florence Cathedral, St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, and the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini. Finally, the Aldine Press, founded by the printer Aldo Manuzio, active in Venice, developed Italic type and the small, relatively portable and inexpensive printed book that could be carried in one's pocket, as well as being the first to publish editions of books in ancient Greek.

Yet cultural contributions notwithstanding, some present-day historians also see the era as one of the beginning of economic regression for Italy (due to the opening up of the Atlantic trade routes and repeated foreign invasions) and of little progress in experimental science, which made its great leaps forward among Protestant culture in the 17th century.

Age of Discovery

The fall of Constantinople led to the migration of Greek scholars and texts to Italy, fueling the rediscovery of Greco-Roman Humanism.[102][103][104] Humanist rulers such as Federico da Montefeltro and Pope Pius II worked to establish ideal cities where man is the measure of all things, and therefore founded Urbino and Pienza respectively. Pico della Mirandola wrote the Oration on the Dignity of Man, considered the manifesto of Renaissance Humanism, in which he stressed the importance of free will in human beings. The humanist historian Leonardo Bruni was the first to divide human history in three periods: Antiquity, Middle Ages and Modernity.[105] The second consequence of the Fall of Constantinople was the beginning of the Age of Discovery.

Italian explorers and navigators from the dominant maritime republics, eager to find an alternative route to the Indies in order to bypass the Ottoman Empire, offered their services to monarchs of Atlantic countries and played a key role in ushering the Age of Discovery and the European colonization of the Americas. The most notable among them were: Christopher Columbus, colonizer in the name of Spain, who is credited with discovering the New World and the opening of the Americas for conquest and settlement by Europeans;[106] John Cabot, sailing for England, who was the first European to set foot in "New Found Land" and explore parts of the North American continent in 1497;[107] Amerigo Vespucci, sailing for Portugal, who first demonstrated in about 1501 that the New World (in particular Brazil) was not Asia as initially conjectured, but a fourth continent previously unknown to people of the Old World (America is named after him);[108] and Giovanni da Verrazzano, at the service of France, renowned as the first European to explore the Atlantic coast of North America between Florida and New Brunswick in 1524.[109]

Incessant warfare

In the 14th century, Northern Italy and upper-central Italy were divided into a number of warring city-states, the most powerful being Milan, Florence, Pisa, Siena, Genoa, Ferrara, Mantua, Verona and Venice. High Medieval Northern Italy was further divided by the long running battle for supremacy between the forces of the Papacy and of the Holy Roman Empire. Each city aligned itself with one faction or the other, yet was divided internally between the two warring parties, Guelfs and Ghibellines.

Warfare between the states was common, invasion from outside Italy confined to intermittent sorties of Holy Roman Emperors. Renaissance politics developed from this background. Since the 13th century, as armies became primarily composed of mercenaries, prosperous city-states could field considerable forces, despite their low populations. In the course of the 15th century, the most powerful city-states annexed their smaller neighbors. Florence took Pisa in 1406, Venice captured Padua and Verona, while the Duchy of Milan annexed a number of nearby areas including Pavia and Parma.

The first part of the Renaissance saw almost constant warfare on land and sea as the city-states vied for preeminence. On land, these wars were primarily fought by armies of mercenaries known as condottieri, bands of soldiers drawn from around Europe, but especially Germany and Switzerland, led largely by Italian captains. The mercenaries were not willing to risk their lives unduly, and war became one largely of sieges and maneuvering, occasioning few pitched battles. It was also in the interest of mercenaries on both sides to prolong any conflict, to continue their employment. Mercenaries were also a constant threat to their employers; if not paid, they often turned on their patron. If it became obvious that a state was entirely dependent on mercenaries, the temptation was great for the mercenaries to take over the running of it themselves—this occurred on a number of occasions.[110]

At sea, Italian city-states sent many fleets out to do battle. The main contenders were Pisa, Genoa, and Venice, but after a long conflict the Genoese succeeded in reducing Pisa. Venice proved to be a more powerful adversary, and with the decline of Genoese power during the 15th century Venice became pre-eminent on the seas. In response to threats from the landward side, from the early 15th century Venice developed an increased interest in controlling the terrafirma as the Venetian Renaissance opened.

On land, decades of fighting saw Florence, Milan and Venice emerge as the dominant players, and these three powers finally set aside their differences and agreed to the Peace of Lodi in 1454, which saw relative calm brought to the region for the first time in centuries. This peace would hold for the next forty years, and Venice's unquestioned hegemony over the sea also led to unprecedented peace for much of the rest of the 15th century. In the beginning of the 15th century, adventurers and traders such as Niccolò Da Conti (1395–1469) traveled as far as Southeast Asia and back, bringing fresh knowledge on the state of the world, presaging further European voyages of exploration in the years to come.

Italian Wars

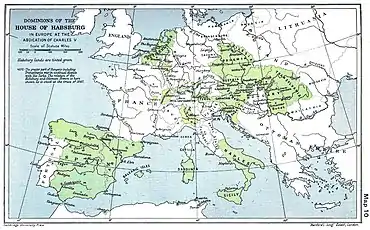

The foreign invasions of Italy known as the Italian Wars began with the 1494 invasion by France that wreaked widespread devastation on Northern Italy and ended the independence of many of the city-states. Originally arising from dynastic disputes over the Duchy of Milan and the Kingdom of Naples, the wars rapidly became a general struggle for power and territory among their various participants, marked with an increasing number of alliances, counter-alliances, and betrayals. The French were routed by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Battle of Pavia (1525) and again in the War of the League of Cognac (1526–30). Eventually, after years of inconclusive fighting, with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559) France renounced all its claims in Italy thus inaugurating a long Habsburg hegemony over the Peninsula.[111]

Much of Venice's hinterland (but not the city itself) was devastated by the Turks in 1499 and again invaded and plundered by the League of Cambrai in 1509. In 1528, most of the towns of Apulia and Abbruzzi had been sacked. Worst of all was the 6 May 1527 Sack of Rome by mutinous German mercenaries that all but ended the role of the Papacy as the largest patron of Renaissance art and architecture. The long Siege of Florence (1529–1530) brought the destruction of its suburbs, the ruin of its export business and the confiscation of its citizens' wealth. Italy's urban population fell in half, ransoms paid to the invaders and emergency taxes drained the finances. The wool and silk industries of Lombardy collapsed when their looms were wrecked by invaders. The defensive tactic of scorched earth only slightly delayed the invaders, and made the recovery much longer and more painful.[112]

From the Counter-Reformation to Napoleon

The history of Italy following the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis was characterized by foreign domination and economic decline. The North was under indirect rule of the Austrian Habsburgs in their positions as Holy Roman Emperors, and the south was under direct rule of the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs. Following the European wars of successions of the 1700s, the south passed to a cadet branch of Spanish Bourbons and the north was under control of the Austrian House of Habsburg-Lorraine. During the Napoleonic era, Italy was invaded by France and divided into a number of sister republics (later in the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy and the French Empire). The Congress of Vienna (1814) restored the situation of the late 18th century, which was however quickly overturned by the incipient movement of Italian unification.

17th century

The 17th century was a tumultuous period in Italian history, marked by deep political and social changes. These included the increase of Papal power in the peninsula and the influence of Roman Catholic Church at the peak of the Counter Reformation, the Catholic reaction against the Protestant Reformation. Despite important artistic and scientific achievements, such as the discoveries of Galileo in the field of astronomy and physics and the flourishing of the Baroque style in architecture and painting, Italy experienced overall economic decline.

Effectively, in spite of Italy having given birth to some great explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci and Giovanni da Verrazzano, the discovery of the New World undermined the importance of Venice and other Italian ports as commercial hubs by shifting Europe's center of gravity westward towards the Atlantic.[113] In addition, Spain's involvement in the Thirty Years' War (1618–48), financed in part by taxes on its Italian possessions, heavily drained Italian commerce and agriculture; so, as Spain declined, it dragged its Italian domains down with it, spreading conflicts and revolts (such as the Neapolitan 1647 tax-related "Revolt of Masaniello").[114]

The Black Death returned to haunt Italy throughout the century. The plague of 1630 that ravaged northern Italy, notably Milan and Venice, claimed possibly one million lives, or about 25% of the population.[115] The plague of 1656 killed up to 43% of the population of the Kingdom of Naples.[116] Historians believe the dramatic reduction in Italian cities population (and, thus, in economic activity) contributed to Italy's downfall as a major commercial and political centre.[117] By one estimate, while in 1500 the GDP of Italy was 106% of the French GDP, by 1700 it was only 75% of it.[118]

18th century

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) was triggered by the death without issue of the last Habsburg king of Spain, Charles II, who fixed the entire Spanish inheritance on Philip, Duke of Anjou, the second grandson of King Louis XIV of France. In face of the threat of a French hegemony over much of Europe, a Grand Alliance between Austria, England, the Dutch Republic and other minor powers (within which the Duchy of Savoy) was signed in The Hague. The Alliance successfully fought and defeated the Franco-Spanish "Party of the Two Crowns", and the subsequent Treaty of Utrecht and Rastatt pass control of much of Italy (Milan, Naples and Sardinia) from Spain to Austria, while Sicily was ceded to the Duchy of Savoy. However, Spain attempted again to retake territories in Italy and to claim the French throne in the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–1720), but was again defeated. As a result of the Treaty of The Hague, Spain agreed to abandon its Italian claims, while Duke Victor Amadeus II of Savoy agreed to exchange Sicily with Austria, for the island of Sardinia, after which he was known as the King of Sardinia. The Spaniards regained Naples and Sicily following the Battle of Bitonto in 1738.

Age of Napoleon

At the end of the 18th century, Italy was almost in the same political conditions as in the 16th century; the main differences were that Austria had replaced Spain as the dominant foreign power after the War of Spanish Succession (though the War of the Polish Succession resulted in the re-installment of the Spanish in the south, as the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies), and that the dukes of Savoy (a mountainous region between Italy and France) had become kings of Sardinia by increasing their Italian possessions, which now included Sardinia and the north-western region of Piedmont.

This situation was shaken in 1796, when the French Army of Italy under Napoleon invaded Italy, with the aims of forcing the First Coalition to abandon Sardinia (where they had created an anti-revolutionary puppet-ruler) and forcing Austria to withdraw from Italy. The first battles came on 9 April, between the French and the Piedmontese, and within only two weeks Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia was forced to sign an armistice. On 15 May the French general then entered Milan, where he was welcomed as a liberator. Subsequently, beating off Austrian counterattacks and continuing to advance, he arrived in the Veneto in 1797. Here occurred the Veronese Easters, an act of rebellion against French oppression, that tied down Napoleon for about a week.

Napoleon conquered most of Italy in the name of the French Revolution in 1797–99. He consolidated old units and split up Austria's holdings. He set up a series of new republics, complete with new codes of law and abolition of old feudal privileges. Napoleon's Cisalpine Republic was centered on Milan. Genoa the city became a republic while its hinterland became the Ligurian Republic. The Roman Republic was formed out of the papal holdings while the pope himself was sent to France. The Neapolitan Republic was formed around Naples, but it lasted only five months before the enemy forces of the Coalition recaptured it. In 1805, he formed the Kingdom of Italy, with himself as king and his stepson as viceroy. In addition, France turned the Netherlands into the Batavian Republic, and Switzerland into the Helvetic Republic. All these new countries were satellites of France, and had to pay large subsidies to Paris, as well as provide military support for Napoleon's wars. Their political and administrative systems were modernized, the metric system introduced, and trade barriers reduced. Jewish ghettos were abolished. Belgium and Piedmont became integral parts of France.[119]

In 1805, after the French victory over the Third Coalition and the Peace of Pressburg, Napoleon recovered Veneto and Dalmatia, annexing them to the Italian Republic and renaming it the Kingdom of Italy. Also that year a second satellite state, the Ligurian Republic (successor to the old Republic of Genoa), was pressured into merging with France. In 1806, he conquered the Kingdom of Naples and granted it to his brother and then (from 1808) to Joachim Murat, along with marrying his sisters Elisa and Paolina off to the princes of Massa-Carrara and Guastalla. In 1808, he also annexed Marche and Tuscany to the Kingdom of Italy.

In 1809, Bonaparte occupied Rome, for contrasts with the pope, who had excommunicated him, and to maintain his own state efficiently,[120] exiling the Pope first to Savona and then to France.

After Russia, the other states of Europe re-allied themselves and defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig, after which his Italian allied states, with Murat first among them, abandoned him to ally with Austria.[121] Defeated at Paris on 6 April 1814, Napoleon was compelled to renounce his throne and sent into exile on Elba. The resulting Congress of Vienna (1814) restored a situation close to that of 1795, dividing Italy between Austria (in the north-east and Lombardy), the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (in the south and in Sicily), and Tuscany, the Papal States and other minor states in the centre. However, old republics such as Venice and Genoa were not recreated, Venice went to Austria, and Genoa went to the Kingdom of Sardinia.

On Napoleon's escape and return to France (the Hundred Days), he regained Murat's support, but Murat proved unable to convince the Italians to fight for Napoleon with his Proclamation of Rimini and was beaten and killed. The Italian kingdoms thus fell, and Italy's Restoration period began, with many pre-Napoleonic sovereigns returned to their thrones. Piedmont, Genoa and Nice came to be united, as did Sardinia (which went on to create the State of Savoy), while Lombardy, Veneto, Istria and Dalmatia were re-annexed to Austria. The dukedoms of Parma and Modena re-formed, and the Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples returned to the Bourbons. The political and social events in the restoration period of Italy (1815–1835) led to popular uprisings throughout the peninsula and greatly shaped what would become the Italian Wars of Independence. All this led to a new Kingdom of Italy and Italian unification.

Frederick Artz emphasizes the benefits the Italians gained from the French Revolution:

- For nearly two decades the Italians had the excellent codes of law, a fair system of taxation, a better economic situation, and more religious and intellectual toleration than they had known for centuries. ... Everywhere old physical, economic, and intellectual barriers had been thrown down and the Italians had begun to be aware of a common nationality.[122]

During the Napoleonic era, in 1797, the first official adoption of the Italian tricolour as a national flag by a sovereign Italian state, the Cispadane Republic, a Napoleonic sister republic of Revolutionary France, took place, on the basis of the events following the French Revolution (1789–1799) which, among its ideals, advocated the national self-determination.[123][124] This event is celebrated by the Tricolour Day.[125] The Italian national colours appeared for the first time on a tricolour cockade in 1789,[126] anticipating by seven years the first green, white and red Italian military war flag, which was adopted by the Lombard Legion in 1796.[127]

Unification (1814–1861)

The Risorgimento was the political and social process that unified different states of the Italian peninsula into the single nation of Italy.

It is difficult to pin down exact dates for the beginning and end of Italian reunification, but most scholars agree that it began with the end of Napoleonic rule and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, and approximately ended with the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, though the last "città irredente" did not join the Kingdom of Italy until the Italian victory in World War I.

As Napoleon's reign began to fail, other national monarchs he had installed tried to keep their thrones by feeding those nationalistic sentiments, setting the stage for the revolutions to come. Among these monarchs were the viceroy of Italy, Eugène de Beauharnais, who tried to get Austrian approval for his succession to the Kingdom of Italy, and Joachim Murat, who called for Italian patriots' help for the unification of Italy under his rule.[128] Following the defeat of Napoleonic France, the Congress of Vienna (1815) was convened to redraw the European continent. In Italy, the Congress restored the pre-Napoleonic patchwork of independent governments, either directly ruled or strongly influenced by the prevailing European powers, particularly Austria.

.jpg.webp)

In 1820, Spaniards successfully revolted over disputes about their Constitution, which influenced the development of a similar movement in Italy. Inspired by the Spaniards (who, in 1812, had created their constitution), a regiment in the army of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, commanded by Guglielmo Pepe, a Carbonaro (member of the secret republican organization),[131] mutinied, conquering the peninsular part of Two Sicilies. The king, Ferdinand I, agreed to enact a new constitution. The revolutionaries, though, failed to court popular support and fell to Austrian troops of the Holy Alliance. Ferdinand abolished the constitution and began systematically persecuting known revolutionaries. Many supporters of revolution in Sicily, including the scholar Michele Amari, were forced into exile during the decades that followed.[132]

The leader of the 1821 revolutionary movement in Piedmont was Santorre di Santarosa, who wanted to remove the Austrians and unify Italy under the House of Savoy. The Piedmont revolt started in Alessandria, where troops adopted the green, white, and red tricolore of the Cisalpine Republic. The king's regent, prince Charles Albert, acting while the king Charles Felix was away, approved a new constitution to appease the revolutionaries, but when the king returned he disavowed the constitution and requested assistance from the Holy Alliance. Di Santarosa's troops were defeated, and the would-be Piedmontese revolutionary fled to Paris.[133]

At the time, the struggle for Italian unification was perceived to be waged primarily against the Austrian Empire and the Habsburgs, since they directly controlled the predominantly Italian-speaking northeastern part of present-day Italy and were the single most powerful force against unification. The Austrian Empire vigorously repressed nationalist sentiment growing on the Italian peninsula, as well as in the other parts of Habsburg domains. Austrian Chancellor Franz Metternich, an influential diplomat at the Congress of Vienna, stated that the word Italy was nothing more than "a geographic expression."[134]

Artistic and literary sentiment also turned towards nationalism; and perhaps the most famous of proto-nationalist works was Alessandro Manzoni's I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed). Some read this novel as a thinly veiled allegorical critique of Austrian rule. The novel was published in 1827 and extensively revised in the following years. The 1840 version of I Promessi Sposi used a standardized version of the Tuscan dialect, a conscious effort by the author to provide a language and force people to learn it.

Those in favour of unification also faced opposition from the Holy See, particularly after failed attempts to broker a confederation with the Papal States, which would have left the Papacy with some measure of autonomy over the region. The pope at the time, Pius IX, feared that giving up power in the region could mean the persecution of Italian Catholics.[135]

Even among those who wanted to see the peninsula unified into one country, different groups could not agree on what form a unified state would take. Vincenzo Gioberti, a Piedmontese priest, had suggested a confederation of Italian states under rulership of the Pope. His book, Of the Moral and Civil Primacy of the Italians, was published in 1843 and created a link between the Papacy and the Risorgimento. Many leading revolutionaries wanted a republic, but eventually it was a king and his chief minister who had the power to unite the Italian states as a monarchy.

One of the most influential revolutionary groups was the Carbonari (charcoal-burners), a secret organization formed in southern Italy early in the 19th century. Inspired by the principles of the French Revolution, its members were mainly drawn from the middle class and intellectuals. After the Congress of Vienna divided the Italian peninsula among the European powers, the Carbonari movement spread into the Papal States, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Modena and the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia.

The revolutionaries were so feared that the reigning authorities passed an ordinance condemning to death anyone who attended a Carbonari meeting. The society, however, continued to exist and was at the root of many of the political disturbances in Italy from 1820 until after unification. The Carbonari condemned Napoleon III to death for failing to unite Italy, and the group almost succeeded in assassinating him in 1858. Many leaders of the unification movement were at one time members of this organization. (Note: Napoleon III, as a young man, fought on the side of the 'Carbonari'.)

In this context, in 1847, the first public performance of the song Il Canto degli Italiani, the Italian national anthem since 1946, took place.[136][137] Il Canto degli Italiani, written by Goffredo Mameli set to music by Michele Novaro, is also known as the Inno di Mameli, after the author of the lyrics, or Fratelli d'Italia, from its opening line.

Two prominent radical figures in the unification movement were Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. The more conservative constitutional monarchic figures included the Count of Cavour and Victor Emmanuel II, who would later become the first king of a united Italy.

Mazzini's activity in revolutionary movements caused him to be imprisoned soon after he joined. While in prison, he concluded that Italy could – and therefore should – be unified and formulated his program for establishing a free, independent, and republican nation with Rome as its capital. After Mazzini's release in 1831, he went to Marseille, where he organized a new political society called La Giovine Italia (Young Italy). The new society, whose motto was "God and the People," sought the unification of Italy.

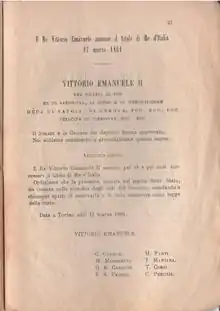

The creation of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of concerted efforts by Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom encompassing the entire Italian Peninsula.

The Kingdom of Sardinia industrialized from 1830 onward. A constitution, the Statuto Albertino was enacted in the year of revolutions, 1848, under liberal pressure. Under the same pressure, the First Italian War of Independence was declared on Austria. After initial success the war took a turn for the worse and the Kingdom of Sardinia lost.

Garibaldi, a native of Nice (then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia), participated in an uprising in Piedmont in 1834, was sentenced to death, and escaped to South America. He spent fourteen years there, taking part in several wars, and returned to Italy in 1848.

After the Revolutions of 1848, the apparent leader of the Italian unification movement was Italian nationalist Giuseppe Garibaldi. He was popular amongst southern Italians.[138] Garibaldi led the Italian republican drive for unification in southern Italy, but the northern Italian monarchy of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia whose government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also had the ambition of establishing a united Italian state. Although the kingdom had no physical connection to Rome (deemed the natural capital of Italy), the kingdom had successfully challenged Austria in the Second Italian War of Independence, liberating Lombardy–Venetia from Austrian rule. On the basis of the Plombières Agreement, the Kingdom of Sardinia ceded Savoy and Nice to France, an event that caused the Niçard exodus, that was the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy.[139] The kingdom also had established important alliances which helped it improve the possibility of Italian unification, such as Britain and France in the Crimean War.

Southern Question

The transition was not smooth for the south (the "Mezzogiorno"). The path to unification and modernization created a divide between Northern and Southern Italy. People condemned the South for being "backwards" and barbaric, when in truth, compared to Northern Italy, "where there was backwardness, the lag, never excessive, was always more or less compensated by other elements".[140] Of course, there had to be some basis for singling out the South like Italy did. The entire region south of Naples was afflicted with numerous deep economic and social liabilities.[141] However, many of the South's political problems and its reputation of being "passive" or lazy (politically speaking) was due to the new government (that was born out of Italy's want for development) that alienated the South and prevented the people of the South from any say in important matters. However, on the other hand, transportation was difficult, soil fertility was low with extensive erosion, deforestation was severe, many businesses could stay open only because of high protective tariffs, large estates were often poorly managed, most peasants had only very small plots, and there was chronic unemployment and high crime rates.[142]

Cavour decided the basic problem was poor government, and believed that could be remedied by strict application of the Piedmonese legal system. The main result was an upsurge in brigandage, which turned into a bloody civil war that lasted almost ten years. The insurrection reached its peak mainly in Basilicata and northern Apulia, headed by the brigands Carmine Crocco and Michele Caruso.[143]

With the end of the southern riots, there was a heavy outflow of millions of peasants in the Italian diaspora, especially to the United States and South America. Others relocated to the northern industrial cities such as Genoa, Milan and Turin, and sent money home.[142]

Liberal Italy (1861–1922)

_-_Cavour_cropped.jpg.webp)

Italy became a nation-state belatedly on 17 March 1861, when most of the states of the peninsula were united under king Victor Emmanuel II of the House of Savoy, which ruled over Piedmont. The architects of Italian unification were Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, the Chief Minister of Victor Emmanuel, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, a general and national hero. In 1866, Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck offered Victor Emmanuel II an alliance with the Kingdom of Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. In exchange Prussia would allow Italy to annex Austrian-controlled Venice. King Emmanuel agreed to the alliance and the Third Italian War of Independence began. The victory against Austria allowed Italy to annex Venice. The one major obstacle to Italian unity remained Rome.

In 1870, France started the Franco-Prussian War and brought home its soldiers in Rome, where they had kept the pope in power. Italy marched in to take over the Papal State. Italian unification was completed, and the capital was moved from Florence to Rome.[144]

In Northern Italy, industrialisation and modernisation began in the last part of the 19th century. The south, at the same time, was overpopulated, forcing millions of people to search for a better life abroad. It is estimated that around one million Italian people moved to other European countries such as France, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg, and to the Americas.

Parliamentary democracy developed considerably in the 19th century. The Sardinian Statuto Albertino of 1848, extended to the whole Kingdom of Italy in 1861, provided for basic freedoms, but the electoral laws excluded the non-propertied and uneducated classes from voting.

Italy's political arena was sharply divided between broad camps of left and right which created frequent deadlock and attempts to preserve governments, which led to instances such as conservative Prime Minister Marco Minghetti enacting economic reforms to appease the opposition such as the nationalization of railways. In 1876, Minghetti lost power and was replaced by the Democrat Agostino Depretis, who began a period of political dominance in the 1880s, but continued attempts to appease the opposition to hold power.

Depretis

Depretis began his term as Prime Minister by initiating an experimental political idea called Trasformismo (transformism). The theory of Trasformismo was that a cabinet should select a variety of moderates and capable politicians from a non-partisan perspective. In practice, trasformismo was authoritarian and corrupt, Depretis pressured districts to vote for his candidates if they wished to gain favourable concessions from Depretis when in power. The results of the 1876 election resulted in only four representatives from the right being elected, allowing the government to be dominated by Depretis. Despotic and corrupt actions are believed to be the key means in which Depretis managed to keep support in southern Italy. Depretis put through authoritarian measures, such as the banning public meetings, placing "dangerous" individuals in internal exile on remote penal islands across Italy and adopting militarist policies. Depretis enacted controversial legislation for the time, such as abolishing arrest for debt, making elementary education free and compulsory while ending compulsory religious teaching in elementary schools.[145]

The first government of Depretis collapsed after his dismissal of his Interior Minister, and ended with his resignation in 1877. The second government of Depretis started in 1881. Depretis' goals included widening suffrage in 1882 and increasing the tax intake from Italians by expanding the minimum requirements of who could pay taxes and the creation of a new electoral system called which resulted in large numbers of inexperienced deputies in the Italian parliament.[146] In 1887, Depretis was finally pushed out of office after years of political decline.

Crispi

Francesco Crispi (1818–1901) was Prime Minister for a total of six years, from 1887 until 1891 and again from 1893 until 1896. Historian R.J.B. Bosworth says of his foreign policy that Crispi:

Pursued policies whose openly aggressive character would not be equaled until the days of the Fascist regime. Crispi increased military expenditure, talked cheerfully of a European conflagration, and alarmed his German or British friends with this suggestions of preventative attacks on his enemies. His policies were ruinous, both for Italy's trade with France, and, more humiliatingly, for colonial ambitions in East Africa. Crispi's lust for territory there was thwarted when on 1 March 1896, the armies of Ethiopian Emperor Menelik routed Italian forces at Adowa, ... In what has been defined as an unparalleled disaster for a modern army. Crispi, whose private life (he was perhaps a trigamist) and personal finances...were objects of perennial scandal, went into dishonorable retirement.[147]

Crispi had been in the Depretis cabinet minister and was once a Garibaldi republican. Crispi's major concerns before during 1887–91 was protecting Italy from Austria-Hungary. Crispi worked to build Italy as a great world power through increased military expenditures, advocation of expansionism, and trying to win Germany's favor even by joining the Triple Alliance which included both Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882 which remained officially intact until 1915. While helping Italy develop strategically, he continued trasformismo and was authoritarian, once suggesting the use of martial law to ban opposition parties. Despite being authoritarian, Crispi put through liberal policies such as the Public Health Act of 1888 and establishing tribunals for redress against abuses by the government.[148]

The overwhelming attention paid to foreign policy alienated the agricultural community which needed help. Both radical and conservative forces in the Italian parliament demanded that the government investigate how to improve agriculture in Italy.[149] The investigation which started in 1877 and was released eight years later, showed that agriculture was not improving, that landowners were swallowing up revenue from their lands and contributing almost nothing to the development of the land. There was aggravation by lower class Italians to the break-up of communal lands which benefited only landlords. Most of the workers on the agricultural lands were not peasants but short-term labourers who at best were employed for one year. Peasants without stable income were forced to live off meager food supplies, disease was spreading rapidly, plagues were reported, including a major cholera epidemic which killed at least 55,000 people.[150]

The Italian government could not deal with the situation effectively due to the mass overspending of the Depretis government that left Italy in huge debt. Italy also suffered economically because of overproduction of grapes for their vineyards in the 1870s and 1880s when France's vineyard industry was suffering from vine disease caused by insects. Italy during that time prospered as the largest exporter of wine in Europe but following the recovery of France in 1888, southern Italy was overproducing and had to split in two which caused greater unemployment and bankruptcies.[151]

Giolitti

From 1901 to 1914, Italian history and politics was dominated by Giovanni Giolitti. He first confronted the wave of widespread discontent that Crispi's policy had provoked with the increase in prices. And it is with this first confrontation with the social partners that the wave of novelty that Giolitti brought to the political landscape between the 19th and 20th centuries was highlighted. No more authoritarian repression, but acceptance of protests and therefore of strikes, as long as they are neither violent nor political, with the (successful) aim of bringing the socialists in the political life of the country.[152][153]

Giolitti's most important interventions were social and labor legislation, universal male suffrage, the nationalization of the railways and insurance companies the reduction of state debt, the development of infrastructure and industry. In foreign policy, there was a movement away from Germany and Austria Hungary and toward the Triple Entente of France, Great Britain and Russia. Starting from the last two decades of the 19th century, Italy developed its own colonial Empire. It took control of Somalia. Its attempt to occupy Ethiopia failed in the First Italo–Ethiopian War of 1895–1896. In 1911, Giolitti's government sent forces to occupy Libya and declared war on the Ottoman Empire which held Libya. Italy soon conquered and annexed Libya (then divided in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica) and the Dodecanese Islands after the Italo-Turkish War. Nationalists advocated Italy's domination of the Mediterranean Sea by occupying Greece as well as the Adriatic coastal region of Dalmatia but no attempts were made.[154]

In June 1914 the left became repulsed by the government after the killing of three anti-militarist demonstrators. Many elements of the left protested against this and the Italian Socialist Party declared a general strike in Italy. The protests that ensued became known as "Red Week", as leftists rioted and various acts of civil disobedience occurred in major cities and small towns such as seizing railway stations, cutting telephone wires and burning tax-registers. However, only two days later the strike was officially called off, though the civil strife continued.

Italy in World War I

Italy entered into the First World War in 1915 with the aim of completing national unity: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence,[156] in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848 with the First Italian War of Independence.[157][158]