Batman Returns

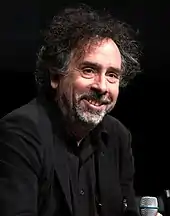

Batman Returns is a 1992 American superhero film directed by Tim Burton and written by Daniel Waters. Based on the DC Comics character Batman, it is the sequel to Batman (1989) and the second installment in the 1989–1997 Batman series. In the film, the superhero vigilante Batman comes into conflict with wealthy industrialist Max Shreck and deformed crime boss Oswald Cobbleplot / Penguin, who seek power, influence, and respect regardless of the cost to Gotham City. Their plans are complicated by Selina Kyle, Shreck's formerly-meek secretary, who seeks vengeance against Shreck as Catwoman. The cast includes Michael Keaton, Danny DeVito, Michelle Pfeiffer, Christopher Walken, Michael Gough, Pat Hingle, and Michael Murphy.

| Batman Returns | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Tim Burton |

| Screenplay by | Daniel Waters |

| Story by |

|

| Based on |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Stefan Czapsky |

| Edited by | Chris Lebenzon |

| Music by | Danny Elfman |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 126 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50–80 million[lower-alpha 2] |

| Box office | $266.8 million[lower-alpha 3] |

Burton had no interest in making a sequel to the successful Batman, believing that he was creatively restricted by the expectations of Warner Bros.. He agreed to return in exchange for significant creative control, including replacing original writer Sam Hamm with Daniel Waters and hiring many of his previous creative collaborators. Waters' script focused more on characterization than on overarching plot, and Wesley Strick was hired to complete an uncredited re-write which (among other elements) provided a master plan for the Penguin. Filming was done from September 1991 to February 1992, on a $50–80 million budget, on sets and sound stages at Warner Bros. Studios and the Universal Studios Lot in California. Special effects primarily involved practical applications and makeup, with some animatronics and computer-generated imagery.

The film's marketing campaign was substantial, including brand collaborations and a variety of merchandise to replicate Batman's success. Released on June 19, 1992, Batman Returns broke several box-office records and earned about $266.8 million worldwide. It failed to replicate the success or longevity of Batman ($411.6 million), however; this was blamed on its darker tone and violent (or sexual) elements, which alienated family audiences and led to a backlash against marketing partners – such as McDonald's – for promoting the film to young children. Reviews were critical of its tone and narrative but more favorable towards the cast, giving near-unanimous praise to Pfeiffer's performance.

Joel Schumacher was hired to direct the third film, Batman Forever (1995), after the relative failure of Batman Returns to make the series more family-friendly. Keaton chose not to reprise his role, disagreeing with Schumacher's vision. Batman Forever was a financial success, but less well-received critically. The fourth film, Batman & Robin (1997), was a critical and commercial failure and is considered one of the worst superhero films ever made. Its failure stalled the Batman film franchise until Batman Begins (2005), the series reboot. Batman Returns has been reassessed as one of the best Batman films in the decades since its release, and its incarnations of Catwoman and Penguin are considered iconic. A comic book, Batman '89 (2021), continued the narrative of the original two Burton films and Keaton is expected to reprise his version of Batman in the DC Extended Universe.

Plot

Two wealthy socialites, dismayed at the birth of their malformed and feral son Oswald Cobblepot, discard the infant in the sewers, where he is adopted by a family of penguins. Thirty-three years later, during the Christmas season, wealthy industrialist Max Shreck is abducted by the Red Triangle gang (a group of former circus workers connected to child disappearances across the country) and brought to their hideout in the Arctic exhibit at the derelict Gotham Zoo. Red Triangle's leader, Oswald – now named Penguin – blackmails Shreck with evidence of his corruption and murderous acts to compel his assistance in reintegrating Oswald into Gotham's elite. Shreck orchestrates a staged attempted kidnapping attempt of the mayor's infant child, allowing Oswald to rescue it and become a public hero. In exchange, Oswald requests access to the city's birth records (ostensibly to learn his true identity) and identifies Gotham's first-born sons.

Shreck attempts to kill his meek secretary, Selina Kyle, by pushing her out a window after she inadvertently uncovers his plot to build a power plant which would covertly siphon and hoard electricity from Gotham. Selina survives, returns home, angrily crafts a costume and adopts the name Catwoman. She returns to work confident and aggressive, catching the attention of visiting billionaire Bruce Wayne. As his alter ego (the vigilante Batman), Wayne investigates Oswald, suspecting that he is connected to Red Triangle. To eliminate opposition to his plant, Shreck convinces Oswald to run for mayor and discredit the incumbent by having Red Triangle wreak havoc throughout Gotham. Batman's efforts to stop the gang eventually bring him into conflict with Catwoman. Selina and Wayne begin dating, while Catwoman allies with Oswald to disgrace Batman.

On the night of the city's Christmas-tree lighting, Oswald and Catwoman kidnap the Ice Princess (Gotham's beauty queen) and lure Batman to the roof above the ceremony. Oswald pushes the Ice Princess to her death with a swarm of bats, framing Batman. When Catwoman objects to the murder and rejects his romantic advances, Oswald attacks her and she falls through a glasshouse. Batman escapes in the Batmobile, unaware that Red Triangle has modified it; this allows Oswald to take it on a remote-controlled rampage. Before regaining control, Batman records Oswald's derogatory tirade against Gotham's citizens. He plays the audio at Oswald's mayoral rally the following day, ruining his image and forcing him to retreat to Gotham Zoo. Oswald forsakes his humanity and embraces the name Penguin, initiating his plan to abduct and kill Gotham's firstborn sons to avenge his own abandonment.

Selina tries to kill Shreck at his charity ball, but Wayne intervenes and they inadvertently discovers each other's secret identities. Penguin crashes the event to kidnap Shreck's son, Chip, but Shreck offers himself instead. Batman neutralizes Red Triangle and stops the kidnapping, forcing Penguin to deploy his missile-equipped penguin army to destroy Gotham. Batman's butler, Alfred Pennyworth, overrides the penguins' control signal and redirects them back to Gotham Zoo. As the missiles destroy the zoo, Batman unleashes a swarm of bats which makes Penguin fall into the contaminated waters of the Arctic exhibit. Catwoman arrives to kill Shreck, rejecting Batman's plea to abandon her vengeance and leave with him. She is shot four times by Shreck, seemingly without effect, because she claims to have two of her nine lives remaining. Catwoman electrocutes Shreck, causing an power surge which apparently kills them both; however, Batman finds only Shreck's charred remains. Penguin returns, but dies of his injuries before he can attack Batman and is laid to rest in the water by his penguins. Sometime later, while Alfred drives him home, Wayne sees Selina's silhouette but finds only a cat (which he takes with him). The Bat-Signal shines above the city, as Catwoman looks on.

Cast

- Michael Keaton as Bruce Wayne / Batman: A billionaire businessman who operates as Gotham's vigilante protector[5][6]

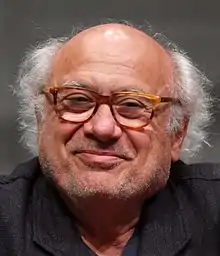

- Danny DeVito as Oswald Cobblepot / Penguin: A deformed crime boss[6]

- Michelle Pfeiffer as Selina Kyle / Catwoman: A meek assistant turned vengeful villain[6][7]

- Christopher Walken as Max Shreck: A ruthless industrialist[6][8][9]

- Michael Gough as Alfred Pennyworth: Wayne's butler and surrogate father[10]

- Pat Hingle as James Gordon: The Gotham City police commissioner and Batman's ally[11]

- Michael Murphy as the Mayor: The city's incumbent mayor[5][12]

The cast of Batman Returns includes Andrew Bryniarski as Max's son Charles "Chip" Schreck and Cristi Conaway as the Ice Princess, Gotham's beauty queen-elect.[13][14][15] Paul Reubens and Diane Salinger appear as Tucker and Esther Cobblepot, Oswald's wealthy, elite parents.[16] Sean Whalen appears as a paperboy; Jan Hooks and Steve Witting play Jen and Josh, Oswald's mayoral image consultants.[lower-alpha 4] The Red Triangle gang includes the monkey-toting Organ Grinder (Vincent Schiavelli), the Poodle Lady (Anna Katarina), the Tattooed Strongman (Rick Zumwalt), the Sword Swallower (John Strong), the Knifethrower Dame (Erika Andersch), the Acrobatic Thug (Gregory Scott Cummins), the Terrifying Clown (Branscombe Richmond), the Fat Clown (Travis Mckenna), and the Thin Clown (Doug Jones).[15][20][21]

Production

Development

After the success of Batman (1989), the fifth-highest-grossing of its time, a sequel was considered inevitable. Warner Bros. Pictures had confidence in its potential and was discussing sequel ideas by late 1989, intending to begin filming the following May;[lower-alpha 5] the studio had purchased the $2 million Gotham City sets at Pinewood Studios in England for at least two sequels. It kept the sets under 24-hour guard because it was cheaper to maintain the existing sets than build new ones. Robin Williams and Danny DeVito were considered to play rogues Riddler and Penguin, respectively.[23] Despite pressure from Warner Bros. to finalize a script and begin filming, Batman director Tim Burton remained uncertain about directing a sequel.[9][23][25] He called the idea "dumbfounded", [sic] especially before Batman's performance was analyzed,[23][25][26] and was generally opposed to sequels: "Sequels are only worthwhile if they give you the opportunity to do something new and interesting. It has to go beyond that, really, because you do the first for the thrill of the unknown. A sequel wipes all that out, so you must explore the next level."[23][26] Batman writer Sam Hamm's initial story idea expanded the character of district attorney Harvey Dent, played in Batman by Billy Dee Williams, and his descent into the supervillain Two-Face. Warner Bros. wanted the main villain to be the Penguin, however, and Hamm believed that the studio saw the character as Batman's most prominent enemy after the Joker. Catwoman was added because Burton and Hamm were interested in the character.[25] Hamm's drafts continued directly from Batman, focusing on the relationship between Wayne and Vicki Vale (Kim Basinger) and their engagement.[9][25] The Penguin was written as an avian-themed criminal who uses birds as weapons; Catwoman was more overtly sexualised, wore "bondage" gear, and nonchalantly murdered groups of men.[25] The main narrative teamed Penguin and Catwoman to frame Batman for the murders of Gotham's wealthiest citizens in their pursuit of a secret treasure. Their quest leads them to Wayne Manor, and reveals the Waynes' secret history. Among other things, Hamm originated the Christmastime setting and introduced Robin, Batman's sidekick, although his idea for assault rifle-wielding Santas was abandoned. Hamm ensured that Batman did not kill anyone, and focused on protecting Gotham's homeless.[9][25] He produced two drafts which failed to renew Burton's interest,[25][26] and the director concentrated on directing Edward Scissorhands (1990) and writing The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993).[9]

Burton was confirmed to direct the sequel in January 1991, with filming scheduled to begin later that year for a 1992 release date.[27] He agreed to return if he received creative control of the sequel; Burton considered Batman the least favorite of his films, describing it as a "little boring at times."[9][25][28] According to Denise Di Novi, his long-time producer, "Only about 50% of Batman was [Burton]"; the studio wanted Batman Returns to be "more of a Tim Burton movie ... [a] weirder movie but also more hip and fun."[28]

Burton replaced key Batman crew with some of his former collaborators, including cinematographer Stefan Czapsky, production designer Bo Welch, creature-effects supervisor Stan Winston, makeup artist Ve Neill, and art directors Tom Duffield and Rick Henrichs.[29] Daniel Waters was hired to replace Hamm; Burton wanted someone with no emotional attachment to Batman and liked Waters' script for the dark comedy Heathers (1988), which matched Burton's intended tone and creative direction.[25][26][28] Burton reportedly disliked Batman producer Jon Peters, demoted him to executive producer of Batman Returns, and effectively barred him from the set.[9] Warner Bros. was the production company and distributor, with production assistance from executive producer Peter Guber's and Peters' Polygram Pictures.[30][31]

Writing

Waters began writing his first draft in mid-1990.[32] Burton's only instructions were that Catwoman had to be more than a "sexy vixen," and that the script not have any connection to Batman, the only concession being a reference to Vale being Wayne's ex-girlfriend.[lower-alpha 6] Waters admitted he did not like Batman and had no interest in continuing its narrative threads or acknowledging the comic book histories of Batman Returns' characters. He said, "[Burton] and I never had a conversation about 'what are fans of the comic books going to think?' ... we never thought about them. We were really just about the art."[25][33][34] Waters also had no interest in avoiding Batman killing people, believing the character should reflect contemporary "darker" times, and the idea of a hero leaving captured villains for the authorities was antiquated.[25] Even so, he only had Batman kill when necessary, believing it should be meaningful, and was unhappy with some of the added on-screen deaths such as Batman using a bomb to blow up a Red Triangle member.[8]

Much of Waters' "bitter and cynical" dialogue for Batman, discussing things such as Gotham City not deserving protection, was removed because Keaton believed Batman should rarely speak when in costume and Burton wanted Batman to be a "wounded soul," not nihilistic.[lower-alpha 7] As a result, the script focused more on Batman Returns' villains. Burton said he initially struggled to understand the appeal of the Penguin's comic book counterpark, because while others such as Batman, Catwoman, and the Joker had more obvious psychological profiles, the Penguin was "just this guy with a cigarette and a top hat."[25] The initial draft made the character closer to a stereotypical DeVito character, resembling more of an abrasive gangster, until Waters and Burton agreed to make him more "animalistic."[32] The pair also decided to make the Penguin a tragic figure abandoned as an infant by his parents, making him a reflection of Batman's childhood trauma at losing his parents.[25] Political and social satire was added, influenced by two episodes of the 1960s television series, Batman, "Hizzoner the Penguin" and "Dizhonner the Penguin", which depict the Penguin running for mayor.[9][25]

Waters changed the Hamm version of Catwoman from a "fetishy sexual fantasy" femme-fatale to a lower-class, disenchanted secretary, writing for her as an allegory of contemporary psychological and sexual feminism.[25][26] Although the character is influenced by feline mythology, such as cats possessing nine lives, Waters and Burton never intended it to be taken literally as a supernatural power and planned for Catwoman to die alongside Shreck during the electrical explosion in the film's denouement.[8][36] Waters devised Max Shreck as an original character, named in honor of actor Max Schreck, to replace the Dent/Two-Face character.[25][26] Shreck was written as an evil industrialist satire who orchestrates the Penguin's mayoral run, because Waters wanted to depict "that the true villains of our world don't necessarily wear costumes." A version of the script also revealed that Shreck was the Penguin's more-favored brother.[9][25] The number of central characters led to the removal of the Robin character, an adult working as a garage mechnanic who helps Batman after Penguin crashes the Batmobile. Burton and Waters were not particularly interested in struggling to retain the character, who Waters described as "the most worthless character in the world."[25][29] The Red Triangle gang, initially conceived as a troupe of performance artists, were changed to circus clowns at Burton's request.[37] Waters' said his 160-page first draft was too outlandish and would have cost $400 million to produce, and he was more restrained going forward.[32] His fifth and final draft focused more on characterization and people interacting than the overall plot.[lower-alpha 8]

Burton and Waters eventually fell out over disagreements about the script and Waters refusing to implement requested changes. Burton hired another writer, Wesley Strick, to refine Waters' work, streamline dialogue, and lighten the tone.[35] Warner Bros. executives also mandated that Strick introduce a master plan for the Penguin, resulting in the addition of the plot to kidnap Gotham's first-born sons and threaten the city with missiles.[25][33][39] Waters said the changes to his work were relatively minor, although in regards to the Penguin's plot he remarked "what the fuck is this shit?"[22][33][35] Waters performed a final revision on the shooting screenplay, and although Strick was on set for four months of filming, performing bespoke rewrites, Waters was the only screenwriter given credit.[22][33][40]

Casting

.jpg.webp)

Keaton reprised his role as Bruce Wayne / Batman but commanded a higher salary, increasing from $5 million for Batman to $10 million for Batman Returns.[25][26][41] Burton wanted to cast Marlon Brando as the Penguin, but was vetoed by Warner Bros. which preferred Dustin Hoffman. Christopher Lloyd and Robert De Niro were also considered, but once Waters re-envisioned the character as a deformed human-bird hybrid, DeVito became the frontrunner.[22][26][42] DeVito was initially reluctant to take part until being convinced by his close friend, Jack Nicholson, who portrayed the Joker in Batman.[26][42] To convey his vision, Burton gave DeVito a painting he had done of a diminutive character sitting on a red-and-white striped ball with the caption "my name is Jimmy, but my friends call me the hideous penguin boy."[8][25][39]

Casting Selina Kyle / Catwoman proved difficult.[25][39] Annette Bening initially secured the role but had to drop out after becoming pregnant and a host of actresses lobbied for the part, including Ellen Barkin, Cher, Bridget Fonda, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Madonna, Julie Newmar, Lena Olin, Susan Sarandon, Raquel Welch, and Basinger. The most prominent appeal, however, came from Sean Young who was previously cast as Vale in Batman before suffering an injury.[lower-alpha 9] Young went to the Warner Bros. lot in a homemade Catwoman costume to make an impromptu audition for Burton, who reportedly hid from her under his desk, although Keaton and producer Mark Canton met with her briefly. She shared video of her efforts with Entertainment Tonight, and Warner Bros. made a statement that Young did not fit their vision for Catwoman.[lower-alpha 10]

The role went to Pfeiffer who was described as a proven actress who got on with Burton, although some publications said it would be a stretch of her acting abilities.[8][26][43] Pfeiffer had also been considered for Vale, but Keaton vetoed the casting because the pair previously dated and he believed her presence would interfere with attempts to reconcile with his wife.[46] She received a $3 million salary, $2 million more than Bening, plus a percentage of the gross profits.[8][26][43][47] Pfeiffer undertook months of training in kickboxing with her stunt double, Kathy Long, and mastering the whip, becoming proficient enough to perform her own stunts with the weapon.[8][22][48][49]

Shreck's appearance was modeled after Vincent Price in an unnamed older film, while Walken based his performance as Shreck on moguls such as Sol Hurok and Samuel Goldwyn.[5][8] He said "I tend to play mostly villains and twisted people. Unsavory guys. I think it's my face, the way I look. If you do something effective, producers want you to do it again and again."[50] Burgess Meredith, who portrayed the Penguin in the 1960s TV show, was scheduled to make a cameo appearance as Penguin's father, Tucker Cobblepot, but he fell ill during filming. He was replaced by Paul Reubens while Diane Salinger portrayed his wife, Esther, both of whom starred in Burton's feature film debut, Pee-wee's Big Adventure (1985).[9][26][51]

Although Robin was removed from the screenplay, the character's development was far enough along that Marlon Wayans was cast in the role (Burton had specifically wanted an African-American Robin), and costumes, sets, and action figures were made. In a 1998 interview, Wayans said he still received residual checks for the two-film deal he signed.[lower-alpha 11] Early reports suggested Nicholson had been asked to return as the Joker, but that he refused to film in England due to the salary tax on foreign talents. Nicholson refuted ever being asked, believing Warner Bros. would not want to replicate the generous financial deal he received for Batman.[53][54][55]

Filming

Principal photography commenced on September 3, 1991.[50][51][56] Burton wanted to film in the United States (U.S.) using American actors because he believed Batman had "suffered from a British subtext."[lower-alpha 12] The economic situation which made filming Batman in the United Kingdom affordable had also changed, making it more cost-effective to remain in the (U.S.)[29] This meant abandoning the Batman sets from England in favor of Burton's new design ethic. Batman Returns was filmed entirely on sets across seven or eight soundstages at Warner Bros. Studios, Burbank in California, including Stage 16, which housed the expansive Gotham Plaza set.[lower-alpha 13] An additional soundstage, Stage 12 at the Universal Studios Lot, was used for the Penguin's expansive arctic exhibit lair.[lower-alpha 14]

Some sets were kept extremely cold for the live Emperor, black-footed, and King penguin varieties.[8][22][26] The birds were flown in for filming on a refrigerated airplane and had a refrigerated waiting area with a swimming pool stocked with half a ton of ice daily and fresh fish.[8][26] DeVito said he generally liked being on set on all of his projects, but disliked the cold atmosphere, and he was the only person somewhat comfortable because of the heavy padding of his costume.[8] To create the penguin army, the live penguins were supplemented with puppets, forty Emperor penguin suits operated by little people, and Computer-generated imagery (CGI).[8][22] People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) protested the production over the use of real penguins, objecting to the birds being moved from their natural environment. Although PETA reportedly said the birds were not mistreated during filming, they later stated they had been denied fresh drinking water in favor of a small chlorinated pool.[22][58] PETA also objected to the penguins being fitted with practical appliances representing weapons and gadgets, which Warner Bros. defended as being lightweight plastic.[59] Burton said that he did not like using real animals because he had an affinity for them and ensured the penguins were treated with care.[60]

Walken described the filming process as very collaborative, recalling how his suggestions to add a blueprint for Shreck's power plant resulted in a model being built within a few hours.[8] The scene of Catwoman putting a live bird in her mouth was performed live and did not use CGI. Pfeiffer said that, in retrospect, she would not have done the stunt as she had not considered the risks of injury or disease involved.[8] For a scene in Penguin's mayoral office, monkey handlers positioned above and below managed the organ grinder monkey as it descended a set of stairs with a note for Penguin. On seeing DeVito in full costume and makeup, it attacked him by leaping at his testicles. DeVito said "The monkey looked at me, froze, and then leapt right at my balls ...Thank god it was a padded costume."[61] A separate scene of Shreck's superstore exploding caused minor injuries to four stuntmen.[22] Principal photography concluded on February 20, 1992, after 170 days or just under six months.[22]

Post-production

Chris Lebenzon served as editor for Batman Returns's 126 minute theatrical cut.[7][62][63] The final scene of Catwoman looking up at the Bat-Signal was filmed during post-production, only two weeks before the film's release. Warner Bros. mandated a scene by added confirming the character survived after test audiences responded positively to Pfeiffer's performance. Pfeiffer was unavailable to film the scene and a stand-in was used.[lower-alpha 15] A scene of Penguin's gang destroying a store filled with Batman merchandise was also removed.[25] Warner Bros. provided a final budget for Batman Returns of $55 million, although it has been reported or estimated to be $50-, $65-, $75-, or 80 million.[lower-alpha 16]

Music

Composer Danny Elfman was initially reluctant to score Batman Returns because he was unhappy about his Batman score being supplemented with pop music by singer-songwriter, Prince.[8] Elfman built on many of his Batman themes, but remarked that he enjoyed working on the Penguin's themes the most because of the character's sympathetic aspects such as his abandonment and death, saying "I'm a huge sucker for that kind of sentimentality."[8][72] Recorded with a studio orchestra on the Sony Scoring Stage in Los Angeles, Elfman's score includes vocals, harps, bells, xylophones, flutes, pianos, and chimes.[73][74] The song, "Face to Face", played during the costume ball scene, was co-written and performed by British rock band Siouxsie and the Banshees.[74] Burton and Elfman fell out during production over the stress of finishing Batman Returns on time, but reconciled shortly afterward.[75]

Design and effects

Batman production designer Anton Furst was replaced by Bo Welch, who understood Burton's visual intentions after two previous collaborations on Beetlejuice (1988) and Edward Scissorhands (1990).[5][26][34] Furst was also already occupied on another project, and would later commit suicide in November 1991.[34] Warner Bros. maintained a high level of security for Batman Returns, requiring the art department to keep their window blinds closed, while cast and crew had to constantly wear ID badges under the film's working title Dictel, a word coined by Welch and Burton meaning "dictatorial" as they were unhappy with the studios "ridiculous gestapo" measures.[76] Welch was also responsible for designing the new Batboat vehicle, a programmable batarang, and the Penguin's assortment of weaponized umbrellas, as well as adding new features to the Batmobile, such as it detaching much of its exterior to fit through tighter spaces; this version was dubbed the "Batmissile."[34][77]

Sets

Every set was redesigned in Welch's style, including the Batcave and Wayne Manor. The expansive sets spread across seven soundstages on the Warner Bros. lot, the largest of which offered 70 ft (21 m) ceilings, and the largest set owned by Universal Pictures.[29][34] Batman Returns was filmed entirely on sets, although some panoramic shots, such as the camera traveling from the base of Shreck's department store up to its cat-head-shaped office, were created using detailed miniatures.[76]

Welch found it difficult to create something new without deviating entirely from Furst's award-winning work. The designs were intended to appear to be a separate district of Gotham, so that if Batman took place on the East Side, Batman Returns was set on the West Side.[34] Welch drew influence from German Expressionism, neo-fascist architecture (including Nazi Germany-era styles), American Precisionism painters, and photos of the homeless living on the streets of affluent areas. He also incorporated Burton's rough sketch of Catwoman, which had a "very S&M kind of look," by adding chains and steel elements that would appear to be holding together a city on the verge of collapse.[22][34][77] The key element, for Welch, came early in design when he realized he wanted to manipulate spaces to convey specific emotions, emphasizing in particular the verticality of the buildings to convey the "huge, overwhelmingly corrupt, decaying city" filled with small people. He said, "the film is about this alienating, disparate world we live in."[34] The wintertime setting was a deliberate choice to take advance of the contrast between black and white scene elements, influenced by films such as Citizen Kane (1941) and The Third Man (1949).[77]

Welch's concept designs began by carving out various building shapes from cardboard alongside images of fascist sculptures and depression era machine age art. The resulting 1 ft (0.30 m) square by 4 ft (1.2 m) tall rough model represented Gotham Plaza, described as a somewhat futuristic, oppressive, and "demented caricature" of Rockefeller center.[34] It was designed to look overbuilt to emphasize it as the generic but oppressive heart of Gotham's governmental corruption. Despite complaints from the financiers about its necessity, Burton insisted on the location featuring a detailed church overshadowed by its plain surroundings.[34][76]

Designs attempted to create the illusion of vast space; the Wayne Manor set was only partially built and consisted mainly of a large staircase and fireplace, but with a large scale that inferred the rest of the structure was massive.[34] Penguin's base was initially scheduled to be built within a standard 35 ft (11 m) tall Warner Bros. soundstage, but Welch considered that it lacked any "majesty" and did not create enough contrast between itself and the "evil, filthy, little bug of a man." A 50 ft (15 m) tall Universal stage was acquired for the production, its raised ceilings making it seem more realistic and less like a set.[76] Minor modifications were made to the set throughout the film to make it appear to be gradually deteriorating.[34] The location featured a large water tank filled with 500,000 U.S. gal (1,900,000 L) of water surrounding a faux ice island.[47] Selina Kyle's apartment featured a large steel beam running through its center to appear as if it had been built around a steel girder, which Welch said made it depressing and ironic.[34] The wood used in building the sets was donated to Habitat for Humanity to help build low cost homes for the impoverished.[22]

Costumes and make-up

Bob Ringwood and Mary E. Vogt served as the costume designers.[5] The pair refined the Batsuit design to create the illusion of mechanical parts built into the torso, intending Batman to more resemble Darth Vader.[22] A total of forty-eight Batsuits were made for Batman Returns, constructed from foam rubber.[22][78] It incorporated a mechanical system of bolts and spikes beneath the chestplate to secure the cowl and cape, because "otherwise, if [Keaton] turned around quickly the cape would stay where it was" due to its weight.[78] Costumer Paul Barrett-Brown said the suit was also given a "generous codpiece" for comfort,[78] and initially included a zippered fly as a concession to allow Keaton to use the bathroom, but Keaton declined because it could be seen by the camera from certain angles.[22] As with the Batman costume, Keaton could not turn his head, but compensated by making bolder, more powerful movements with his lower body.[8]

The Catwoman outfit was made from latex because it was designed to be "black and sexy and tight and shiny."[79] The material was chosen because of its association with "erotic and sexual" situations, reflecting the character's transition from a repressed secretary to an extroverted, erotic female.[78] Some padding was added because Pfeiffer was less physically endowed than Bening, however this worked to Pfeiffer's advantage as Barrett-Brown said if it was too tight it "would reveal the genital area so thoroughly that you'd get an X certificate."[78] Ringwood and Vogt were concerned the latex material would tear because it would not be difficult to repair, so anywhere from 40 to 70 Catwoman suits were made as a backup by Western Costume, the Warner Bros. costume department, and a Los Angeles-based clothing manufacturer called Syren, at a cost of $1,000 each.[78][22][79] Other versions were made for Pfeiffer based on a cast of her body which was still so tight that she had to be covered in baby powder to help wear it.[79] Barrett-Brown explained that because of the material, it was possible to get into the suit when dry but they could not re-use the suits because of sweat and body oils.[78] Vin Burnham was responsible for constructing Catwoman's headpiece and mask.[22]

Burton was influenced to add the stitching by calico cats, but with the stitching of the parts coming apart. Ringwood and Vogt struggled with how to add stitching to latex; they initially attempted to sculpt stitching and glue them on but did not like how it looked and went over the suit liberally with liquid silicon while it was worn, which added a shine to everything.[79] Pfeiffer said wearing the suit was like wearing a second skin, but when worn for long periods it was uncomfortable, there was no way to use the restroom while wearing it, and it would become stuck to her skin, occasionally causing rashes. She found the mask similarly confining, describing it as choking her or "smashing my face," and would catch the claws on various things.[8][69]

Stan Winston Studio was tasked with creating an "over-the-top Burtonesque" visual for the Penguin design without completely obscuring DeVito's face. Concept artist Mark McCreery developved a variety of sketches for the look, from which effects team Legacy Effects built different noses onto a lifecast of DeVito's face. Winston was unhappy with the "pointy nose" shapes and began sculpting ideas himself out of clay, taking influence from his work on The Wiz (1978) which involved a forehead and brow prosthetic appliance for large-beaked creatures. The final makeup included a T-shaped appliance that went over DeVito's noise, lip, and brow, as well as crooked teeth, whitened skin, and dark circles under his eyes. Ve Neill was responsible for applying the makeup which was built by John Rosengrant and Shane Mahan.[80] The several pounds of facial prosthetics, body padding, and prosthetic hands took four and a half hours to apply to DeVito to portray the Penguin; this was reduced to three hours by the end of filming.[8][26][42] An air-bladder was added to the costume to help reduce its weight.[78] DeVito also helped create the Penguin's black saliva with the make-up and effects teams, using a mild mouthwash and food coloring, which he had to squirt into his mouth before filming; he said it did not taste too bad.[8] Burton described DeVito as completely in-character once in costume, such that he "scared everybody." While re-dubbing some of his dialogue, DeVito struggled to get into character without the makeup and had it applied to improve his performance.[80] Because of the secrecy regarding his character's appearance prior to marketing, DeVito was not allowed to discuss it with others, including his family.[26][42] A photo did leak to the press, and Warner Bros. employed a firm of private investigators in a failed attempt to track down the source.[47]

Penguins

Stan Winston Studio also provided animatronic penguins and costumes to supplement Penguin's arm. Thirty animatronic versions were made, ten each for the black-footed (18 in (46 cm)), King (32 in (81 cm)), and Emperor (36 in (91 cm)) varieties.[8][22][81] Penguin costumes were worn by little people actors were slightly larger than the animatronics. The actors controlled the walking while the mechanized heads were remote-controlled and the wings puppeteered.[81] Black-dyed chicken feathers were used for the penguin bodies.[8][22] McCreery's designs for the penguin army included a flamethrower weapon which was eventually replaced with a rocket launcher. Mechanical effects designers Richard Landon and Craig Caton-Largent supervised the manufacture of the animatronics, which required nearly 200 different mechanical parts to control the head, neck, eyes, beaks, and wings.[81] Boss Film Studios produced the CGI penguins.[8][22]

Release

Context

By the theatrical summer of 1992 (beginning the last week of May), the film industry was struggling. Ticket sales were at their lowest in fifteen years, and rising film production costs, as well as several box office failures in 1991, meant many independent and even some major film studios were financially struggling.[82] Over 89 films were scheduled for release during the peak summer season, including A League of Their Own, Alien 3, Encino Man, Far and Away, Patriot Games, and Sister Act.[24][68][82] Studios had to carefully schedule their releases to avoid competition from more than six anticipated blockbusters, including Lethal Weapon 3 and Batman Returns, and the 1992 Summer Olympics.[68] Batman Returns was predicted to be the summer's biggest success, and other studios were reported to be concerned about releasing their films within even a few weeks of its debut.[68][83] Paramount Pictures increased the budget of Patriot Games from $29 million to $43 million just to make it more competitive with Batman Returns and Lethal Weapon 3.[68][82]

Marketing

| External video | |

|---|---|

Franchising had not been considered an important aspect of Batman's release. However, after merchandise contributed about $500 million to its $1.5 billion total earnings, it was made a priority for Batman Returns.[8][9][84] Warner Bros. deliberately delayed any major promotion until February 1992, to avoid oversaturation and risking driving away audiences.[lower-alpha 17] A 12-minute promotional reel debuted at WorldCon in September 1991, alongside a black-and-white poster featuring a silhouette of Batman, which was described as "mundane" and uninspiring. A trailer was released in 5,000 theaters in February 1992, as well as a new poster depicting a snowswept Batman logo.[22][77] The campaign focused on the three central characters—Batman, Penguin, and Catwoman, which Warner Bros. believed would offset the loss of Nicholson's popularity.[82][85] Over two-thirds of the 300 posters Warner Bros. installed at various public locations were stolen. Warner Bros. eventually offered 200 limited-edition posters for $250, signed by Keaton, who donated his earnings to charity.[22][85][86]

Over $100 million was expected to be spent on marketing, including $20 million by Warner Bros. for commercials and trailers, and a further $60 million by merchandising partners including McDonald's, Ralston Purina, Kmart, Target Corporation, Venture Stores, and Sears, which planned to host about 300 Batman shops in its stores.[22][84][85] McDonald's converted 9,000 outlets into official Gotham City restaurants, offering Batman-themed packaging and a cup-lid that doubled as a flying disc.[84] CBS aired a television special, The Bat, The Cat, The Penguin ... Batman Returns, and Choice Hotels sponsored an hour-long TV special, The Making of Batman Returns.[22][84] Television advertisements featured Batman and Catwoman fighting over a can of Diet Coke, while the Penguin and his penguins promoted Choice Hotels. Advertisements also appeared on billboards and in print, including three consecutive pages in some newspapers, which were targeted at older audiences.[85]

Box office

The premiere of Batman Returns took place on June 16, 1992, at Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. Two blocks of Hollywood Boulevard were shuttered for over 3,000 fans, 33 TV film crews, and 100 photographers. Afterward, a party was held on the Gotham Plaza set on Soundstage 16 for guests including Keaton, Pfeiffer, DeVito, Burton, Di Novi, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Faye Dunaway, James Caan, Mickey Rooney, Harvey Keitel, Christian Slater, James Woods, and Reubens.[57]

In The United States (U.S.) and Canada, Batman Returns, received a limited preview release on Thursday, June 18, earning $2 million.[8][24][71] It received a wide release on June 19, being shown on an above-average 3,000 screens in 2,644 theaters.[8][24][87] During its opening weekend, Batman Returns earned $45.7 million, an average of $17,729 per theater, making it the number 1 film ahead of Sister Act ($7.8 million) in its fourth weekend and Patriot Games ($7.7 million) in its third. This figure broke the record for the highest-grossing opening weekend, previously set by Batman ($42.7 million), and made Batman Returns the highest-grossing opening weekend of the year, replacing Lethal Weapon 3 ($33.2 million).[24][87][88] The film would hold the record for having the biggest opening weekend of all time until it was surpassed by Jurassic Park ($50.1 million) the next year.[89] Performance analysis suggested Batman Returns could become one of the highest-grossing films ever. Warner Bros. executive Robert Friedman said "we opened it the first real weekend when kids are out of school. The audience is everybody, but the engine that drives the charge are kids under 20."[24] Patriot Games producer, Mace Neufeld, said other films benefited from overflow audiences for Batman Returns who did not want to wait in the long queues or could not access the sold-out screenings.[24]

In its second weekend, Batman Returns earned $25.4 million, a 44.3% drop, making it the number 1 film ahead of the debuting Unlawful Entry ($10.1 million) and Sister Act ($7.2 million).[90][91] By its third weekend, Batman Returns became the second fastest film to gross $100 million (11 days) behind the fastest film, Batman (10 days).[92] It remained the number 1 film with a gross of $13.8 million, a further 45.6% drop, ahead of the debuting A League of Their Own ($13.7 million) and Boomerang ($13.6 million).[91][93] The Washington Post described the week-on-week drops as "troublesome," and industry analysis suggested Batman Returns would not replicate the longevity of Batman's theatrical run.[91][22] Batman Returns never regained the number 1 position, falling to number four in its fourth weekend, and leaving the top-ten highest-grossing films by its seventh. It left theaters in late October after 18 weeks, with a total gross of $162.8 million.[94][95] This made Batman Returns the third highest-grossing film of 1992, behind Home Alone 2: Lost in New York ($173.6 million) and Aladdin ($217.3 million).[88]

Outside of the U.S. and Canada, Batman Returns is estimated to have earned a further $104 million, including a record-setting £2.8 million opening weekend in the United Kingdom, breaking the record set by Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), and making it the first film to gross more than £1 million in a single day.[lower-alpha 18] Worldwide, Batman Returns earned a cumulative gross of $266.8 million making it the sixth-highest-grossing film of 1992, behind Lethal Weapon 3 ($321.7 million), Basic Instinct ($352.9 million), Home Alone 2: Lost in New York ($359 million), The Bodyguard ($410.9 million), and Aladdin ($504.1 million).[96]

Reception

Critical response

Batman Returns was released to a polarized reception from professional critics.[5][22][26] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale.[102]

Several reviewers contrasted Batman Returns with Batman, with some suggesting the sequel was superior in many ways, offering faster pacing, as well as more comedy and depth, while avoiding the "dourness" and "tedium" of Batman.[lower-alpha 19] Critics genereally agreed that Burton's creative control made Batman Returns a more personal work than Batman, creating something "fearlessly" different that could be judged on its own merits.[104][107] Even so, critics such as Kenneth Turan said that Burton's innovative visuals, while impressive, made Batman Returns feel cheerless, claustrophobic, and unexciting, while often being emphasized at the expense of the plot. [7][70][106] Owen Glieberman wrote that the Burton's fantastical elements were undermined because he avoids establishing a base of normality.[7]

The narrative received a mixed response. Some reviews praised the first and second acts, as well as interesting characters that could evoke feelings in the audience.[lower-alpha 20] Others said it lacked suspense, thrills, or clever writing, being overwhelmed by too many characters and near-constant banter.[lower-alpha 21] The ending was often criticized for lackluster action scenes, and failing to bring the separate character narratives to a satisfactory conclusion.[103][104] Janet Maslin remarked that Burton cared mostly about visuals with narrative being a secondary consideration.[104] Gene Siskel said the emphasis on characterization was a detriment, because the sympathetic villains left him hoping Batman would not win, but that each character would find emotional peace.[110]

Reviews generally agreed that despite Keaton's abilities, his character was ignored by the script in favor of the villains, and scenes without him were among the best.[lower-alpha 22] Todd McCarthy described the character as a symbol of good rather than a psychologically complete character, and Ebert lamented that Batman Returns depicts being Batman as a curse instead of a heroic power fantasy.[12][105][111] In contrast, Peter Travers said that while the faster pace left little room to explore Batman, Keaton's "manic depressive hero" was a deep and realized character.[113] DeVito's performance was praised for his energy, unique characterization, and ability to convey the tragedy of his character despite the encompassing costumes and prosthetics. Desson Howe said Burton's focus on the Penguin demonstrated his sympathy for the character.[lower-alpha 23] Some publications considered DeVito an inferior followup to Nicholson's Joker, whp conveyed pity and sympathy but did not instill fear.[lower-alpha 24]

Pfeiffer received near unanimous praise as the film's standout performance, as a passionate, sexy, ambitious, intelligent, intimidating, and fierce embodiment of feminism who offered the only respite from the otherwise dark tone.[lower-alpha 25] Even so, Jonathan Rosenbaum said she did not live up to Nicholson's villain.[108] The scenes shared by Batman and Catwoman were described by Turan as the film's most interesting, and Travers said that when the pair take off their masks during the ending, they look "lost and touchingly human." Burr said the ballroom scene, in which they realize each other's secret identities, was more emotional than anything present in Batman.[106] Ebert lamented that their sexual tension seemed to have been undercut to meet the standards of younger audiences.[12][70][113] Walken's performance was described as "wonderfully debonair", funny, and engaging, providing a villain who would have could have carried Batman Returns alone.[lower-alpha 26]

Welch's production design was generally praised, offering an sleeker, brighter, authoritarian visual style compared to Furst's "brooding" oppressive aesthetic.[lower-alpha 27] McCarthy described Welch's ability to physically realize Burton's imaginative universe as an achievement, although Gene Siskel described Welch as a "toy shop window decorator" compared to Furst's works.[105][110] The costumes and makeup effects were also praised, with Maslin saying those images would linger in the imagination long after the narrative had been forgotten.[103][104] Czapsky's cinematography was well-received, giving a "lively" aesthetic to even the subterranean sets.[104] The violent, mature, and sexual content, such as kidnappings and implied child murder, was often criticized as inappropriate for younger audiences.[lower-alpha 28]

Accolades

At the 46th British Academy Film Awards, Batman Returns was nominated for Best Makeup (Ve Neill and Stan Winston) and Best Special Visual Effects (Michael Fink, Craig Barron, John Bruno, and Dennis Skotak).[116] For the 65th Academy Awards, Batman Returns received a further two nomations: Best Makeup (Neill, Ronnie Specter, and Winston) and Best Visual Effects (Fink, Barron, Bruno, and Skotak).[117] Neill and Winston won the award for Best Make-up at the 19th Saturn Awards. The film also received four further nominations for Best Fantasy Film, Best Supporting Actor (DeVito), Best Director (Burton), and Best Costume Design (Bob Ringwood, Mary Vogt, and Vin Burnham).[118] DeVito was nominated for Worst Supporting Actor at the 13th Golden Raspberry Awards, and Pfeiffer for Most Desirable Female at the 1993 MTV Movie Awards.[119][120] Batman Returns was also nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.[121]

Post-release

Performance analysis and aftermath

The U.S. and Canadian box office underperformed across 1992, with admissions down by up to 5% and about 290 million tickets sold, compared to over 300 million in each of the preceding four years. Industry professionals blamed the drop on the perceived lack of quality of the films being released, considering them too derivative or dull to attract audiences. Even those films considered to be successful experienced significant box office drops week-on-week from what appeared to be negative word-of-mouth among audiences. Industry executive, Frank Price, said the releases were not attracting the younger audiences and children that were vital to a film's success. Rising ticket prices, competition from the Olympics, and an economic recession were also considered to be contributing factors in the declining box office.[122] Batman Returns and Lethal Weapon 3 contributed to Warner Bros.'s best first-half-year in its history and were expected to return over $200 million to the studio from box office takings. Even so, Batman Returns was considered a disappointment as a sequel to the fifth-highest-grossing film ever made, falling approximately $114.8 million short of Batman's $411.6 million theatrical gross.[lower-alpha 29] By July 1992, anonymous Warner Bros. executives were reported to have complained "it's too dark. It's not a lot of fun."[5]

Despite its PG-13 rating by the Motion Picture Association, warning parents that a film may contain strong content unsuitable for children, some audiences, particularly parents, reacted poorly to Batman Returns' violent and sexualized content, with the studio receiving thousands of complaint letters.[8][41][122] Waters recalled the aftermath of one screening: "It's like kids crying, people acting like they've been punched in the stomach and like they've been mugged."[5] He had anticipated some backlash and "relished that reaction" but part of him was "like, 'oops'."[125] McDonald's was criticized for its child-centric promotion and toys, and withdrew the Batman Returns campaign in September 1992.[lower-alpha 30] Burton remarked, "I like [Batman Returns] better than the first one. There was this big backlash that it was too dark, but I found this movie much less dark."[127] Although much of Hamm's work was replaced, he defended Burton and Waters, saying, outside of the merchandise, Batman Returns was never presented as child-friendly.[125]

Warner Bros. chose to move forward with the series but without Burton, who was described as "too dark and odd for them," and replaced him with Joel Schumacher.[41] A rival studio executive said "if you bring back Burton and Keaton, you're stuck with their vision. You can't expect Honey, I Shrunk the Batman," a reference to science-fiction comedy Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989).[126] A lawsuit was brought against Warner Bros. by executive producers, Benjamin Melniker and Michael Uslan, who alleged they originally purchased the film adaptation rights to the Batman character, but had been denied their share of the profits from Batman and Batman Returns by the studio's Hollywood accounting practices—a method used by studios to artificially inflate a film's production costs, making it appear unprofitable and limiting royalty or tax payouts. The court decided in Warner Bros. favor, citing a lack of evidence.[128][129]

Home media

Batman Returns was released on Video Home System (VHS) and Laserdisc on October 21, 1992.[22][130][131] The VHS was priced lower than average at $24.98 to encourage high sales and rental figures. Estimates suggested Batman Returns would sell millions of units and be a well-performing rental, but its success would be restricted by its mature and violent content that would appeal less to children, the main audience driving purchases.[130] Batman Returns was released on DVD in 1997 with no additional features.[132][133] An Anthology DVD box set was released in October 2005, containing all the films in the Burton/Schumacher Batman film series. The Batman Returns inclusion featured commentary by Burton as well as The Bat, The Cat, and The Penguin special about the making of the film, part four of the documentary Shadows of the Bat: The Cinematic Saga of the Dark Knight, notes on the development of costumes, make-up and special effects, as well as the music video for "Face to Face."[134]

The same Anthology was released on Blu-ray in 2009, alongside a standalone Batman Returns Blu-ray release.[132][135] A 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray release, including a standard Blu-ray and digital version, was released in 2019. Restored from the original 35mm negative, the release included the special features from the Anthology releases.[136][137] A separate 4K Collector's Edition was released in 2022, featuring a steelbook case with original cover art, character cards, and a double-sided poster, as well as previously released special features.[138] Elfman's score was released in 1992 on Compact Disc (CD). An expanded album was released in 2010 on CD.[74]

Other media

.jpg.webp)

About 120 licensed products were released alongside Batman Returns including action figures and toys by Kenner Products, Catwoman-themed clothing, toothbrushes, roller skates, T-shirts, underwear, sunglasses, towels, beanbags, mugs, weightlifting gloves, throw pillows, cookie cutters, commemorative coins, playing cards, costume jewelry, cereal, a radio-controlled Batmobile, and tortilla chips shaped like the Batman logo.[22][84][85] Although there were about the same number of products released for Batman, there were fewer licensees so Warner Bros. could retain greater oversight[84][85] The release of Batman: The Animated Series later that year was also anticipated to extend the success of merchandising long after Batman Returns had left theaters. Warner Bros. used holographic labels developed by American Bank Note Holographics to combat counterfeit products.[84]

The film novelization, by Craig Shaw Gardner, was released in July 1992.[16][139] A rollercoaster, Batman: The Ride, was built at Six Flags Great America at a cost of $8 million, and later replicated at other Six Flags locations, alongside a Batman stunt show.[22][84] Several video game adaptations, all titled Batman Returns, were released by multiple developers across several platforms, including Game Gear, Master System, Sega Genesis, Sega CD, Amiga, MS-DOS, and Atari Lynx; the Super Nintendo Entertainment System version was the most successful.[lower-alpha 31]

Batman '89, a comic book series released in 2022, continues the narrative of Burton's original two films, ignoring the Schumacher sequels. Set a few years after the events of Batman Returns, Batman '89 depicts the transformation of district attorney Harvey Dent into Two-Face, and introduces Robin. The series was written by Hamm with art by Joe Quinones.[144] In 2021, to celebrate the 80th anniversary of the Penguin's first comic book appearance, DeVito wrote a comic book story, "Bird Cat Love,"about the Penguin and Catwoman falling in love and solving the COVID-19 pandemic.[145][146] The Red Triangle Gang made their first appearance outside Batman Returns in 2022, in the comic book Robin #15.[147][148]

Thematic analysis

Duality

Critic David Crow believed that duality was a major aspect of Batman Returns, and that Catwoman, Penguin, and Shreck, all represent warped reflected aspects of Batman.[25][109] Like Wayne / Batman, Selina / Catwoman is driven by trauma and is conflicted over her principles and desires, but she seeks vengeance, unlike Batman's justice.[6][107] Catwoman agrees with Batman's appeal, that they are "the same, split right down the center," but they still differ too much to be together.[25] Critics, Darren Mooney and Betsy Sharkey suggest that Penguin reflects Batman's origin, each of them losing their parents at a young age. Shreck says that if not for his abandonment, Cobblepot and Wayne may have even been in the same social circles. However, where Batman takes is depicted as content in his loneliness, the Penguin wants acceptance, love, and respect, despite his quest for revenge.[5][34] To Mooney, Batman Returns hints that Batman's issues with Penguin are personal rather than moral because Batman takes some pride in being a "freak" and unique, and he resents Penguin for always displaying his "freakishness".[5] Shreck represents Wayne's public persona if it was driven purely by greed, vanity, and self-interest, a populist industrialist who wins favor with cheap presents tossed into a crowd.[25]

Commercialism and loneliness

Crow saw Batman Returns as a denouncement of Batman's real-world cultural popularity and merchandising, especially in the wake of the previous Batman film. He noted that a scene of a store filled with Batman merchandise being destroyed was removed from the film.[25] Crow and Mooney wrote that Batman Returns is "saturated with Christmas energy," but it rejects the conventional norms of the season and becomes an anti-Christmas film, critquing the over-commercialism and lack of true goodwill towards others. Shreck cynically exploits Christmas tropes for his own ends, falsely portraying himself as selfless and benevolent, while the various perversions of Penguin's Red Triangle gang are a more overt rejection of the holiday.[5][25]

There is a focus on loneliness and isolation during Christmas, particularly Wayne, who is introduced, sitting alone in his vast mansion, seemingly inert until the Bat-Signal shines in the sky. He makes a connection with Kyle, but ultimately the things they share cannot overcome their differences, and Wayne ends the film as he started it, alone.[5] Critic Todd McCarthy identified isolation as a theme common to much of Burton's work, which he emphasizes in his three main characters.[105]

Authors, Rebecca Roiphe and Daniel Cooper, wrote that Batman Returns was not anti-semetic but did contain anti-semetic imagery, particularly the Penguin who they believed embodied Jewish stereotypes such as " ... his hooked nose, pale face and lust for herring," who is "unathletic and seemingly unthreatening but who, in fact, wants to murder every firstborn child of the gentile community." The pair continued that Penguin joins forces with Shreck, who has a Jewish-sounding name, to disrupt and taint Christmas, and therefore Christian traditions.[149][150]

Sexuality and misogyny

Batman Returns features overt elements of sex and sexuality. Critic Tom Breihan described Catwoman's vinyl catsuit as "pure BDSM," including the whip she wields as a weapon. The dialogue is replete with sexual double entendres, particularly from Penguin and Catwoman, and even her fights with Batman are charged with her sensually licking his face.[25][151] Selina / Catwoman is repeatedly marginalized by the central male characters: Shreck pushes her out of a window, the Penguin tries to kill her when she spurns his advances, and Batman attempts to capture her. She fashions a catsuit to give order, sanity, and power back to her, but the suit is gradually damaged over the course of Batman Returns' narrative and her sanity decays with it. Her final choice is to reject Batman's offer of a happy ending, by abandoning her revenge against Shreck, because to surrender herself to Batman's will would be to let another man control her for his own purpose.[25]

Power and politics

Power is a central theme for several characters. As Shreck states, "There's no such thing as too much power; if my life has a meaning that's the meaning."[25] Shreck uses his money to gain personal power, and Batman uses his fortune to fund his war against crime, in contrast to Penguin who was of the same access to materialistic goods and abandoned because he did not fit the image expected of his parents' station.[25] Kyle gains power by donning the Catwoman costume and embracing her anger and sexuality.[106][107]

Shreck convinces Penguin to run for mayor to further his own goals while the Penguin seeks out the acceptance and respect it will afford him. Critic Caryn James wrote that Batman Returns features "sharp political jabs" inferring that money and image are more important than anything else.[111] As seen in Batman, when the Joker earns the citizens' adoration by throwing them piles of money, Shreck and Penguin gain the support of the populace through spectacle, pandering, and corporate showmanship. The Penguin describes how he and Shreck are both seen as monsters, but that Shreck is a "well-respected monster and I, to date, am not." James said that the Penguin only wants to change the superficial perception of himself because he wants to be accepted, but has no interest in truly being the type of person people would love.[9][25][111] It is only when the fickle voters turn on him that he resorts to his plans to kill infants that had the chances he never had. Crow believed that Burton was the most sympathetic to Penguin and so spent the most time with his character.[25]

Legacy

Cultural influence

.jpg.webp)

Retrospectives in the 2010s and 2020s remarked how Batman Returns had developed an enduring legacy since its release, with Comic Book Resources describing it as the most iconic comic book movie ever made. Although initially criticized for its mix of the superhero and film noir genres, Batman Returns established trends such as dark tones and complex characters that have since become an expectation of many major blockbusters.[8][9][152] Some publications argued that its "disturbing imagery", exploration of morality, and satire of corporate politics seemed even more relevant in the modern day, as did the themes of predujice and feminism explored through Catwoman.[153][152] Burton said that, at the time, he believed Batman Returns was exploring new territory, but that it might be considered "tame" by modern standards.[8] The Ringer wrote that Burton's "weird and unsettling" sequel had led the way for future auteurs such as Christopher Nolan, Peter Jackson, and Sam Raimi to move into mainstream films.[9]

Collider described it as the first "anti-blockbuster", which went against expectations to deliver a superhero film that does not feature much action and is set during Christmas despite its July release.[154] Because of this Christmas setting, some publications have identified it as part of Burton's unofficial Christmas trilogy, bookended by Edward Scissorhands and The Nightmare Before Christmas, and it has become a regular alternative-festive film alongside films such as Die Hard (1988).[5][9][152][154] Various aspects of the production, such as the performances, score, and visual aesthetic are also considered iconic influencing Batman-related media and incarnations of the characters for decades after, such as the Batman Arkham video games.[152][153]

Modern reception

In the years since its release, Batman Returns has been positively critically reapprasied.[152][155] It is now regarded as among the best superhero films ever made,[lower-alpha 32] one of the best sequel films,[lower-alpha 33] and the best Batman films made.[lower-alpha 34][178] Screen Rant named it the best Batman film of the 20th century,[153] and, in 2018, GamesRadar+ named it the best Batman film.[179] Batman Returns also appeared at number 401 on Empire's 2008 list of the 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[180]

Waters recalled being told that Batman Returns was a "great movie for people who don't like Batman," a criticism he accepted.[33][154] Although the film was criticized for depicting Batman killing people, Waters said "to me, Batman not killing [the Joker (as portrayed by Heath Ledger)] at the end of The Dark Knight (2008) after proving he can get out of any prison, it's like 'Come on. Kill Heath Ledger.'".[8][25] Waters believed that the reception to Batman Returns was improving with time, especially following the release of The Batman (2022).[33]

Critic Brian Tallerico argued that the elements which originally upset critics and audiences alike, are what makes it still "revelatory ... It's one of the best and strangest movies of its kind ever made."[136] Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes offers a 80% approval rating from the aggregated reviews of 84 critics, with an average score of 6.6/10. The website's critical consensus says: "Director Tim Burton's dark, brooding atmosphere, Michael Keaton's work as the tormented hero, and the flawless casting of Danny DeVito as The Penguin and Christopher Walken as, well, Christopher Walken make the sequel better than the first."[181] The film has a score of 68 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 23 critics' reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[182]

Pfeiffer's Catwoman is considered iconic, a feat of characterization and performance as a strong feminist character that influenced subsequent female superhero led films.[lower-alpha 35] Pfeiffer's incarnation is also generally regarded as the best cinematic adaptation of the character, influencing future adaptations such as Zoë Kravitz's in The Batman,[lower-alpha 36] one of the best comic book film characters, and among the greatest cinematic villains.[lower-alpha 37] In 2022, Variety listed Pfeiffer's performance as the second best superhero performance of the preceding fifty years, behind Ledger.[197] DeVito's rendition of the Penguin is similarly considered iconic,[lower-alpha 38] and has been listed by some publications as one of the best cinematic Batman villains.[lower-alpha 39]

The Batman actor Robert Pattinson stated in interviews that Batman Returns is his personal favourite Batman film. The actor called the film "a masterpiece" and stated that "Batman Returns is terrifying… I remember watching as a little kid and even watching it now it's one of the most disturbing things I've ever seen."[209]

Sequels

Following the reception of Batman Returns, Warner Bros. intended to continue the series without Burton.[8][41][125] Burton recalled, "I remember toying with the idea of doing another one. And I remember going into Warner Bros. and having a meeting. And I'm going, 'I could do this or we could do that.' And they go like, 'Tim, don’t you want to do a smaller movie now? Just something that’s more [you]?' About half an hour into the meeting, I go, 'You don't want me to make another one, do you?' ... so, we just stopped it right there."[125][8] The studio replaced Burton with Joel Schumacher, who could make something more family- and merchandise-friendly.[8][41][125] Although Burton and Keaton were supportive of the new director, Keaton also left the series because, "[the film] just wasn't any good, man."[lower-alpha 40] Industry press suggested Keaton had also asked for a $15 million salary and a percentage of the profits, although his producing partner, Harry Colomby, said money was never an issue.[125]

Burton served as an executive producer for the third film, Batman Forever (1995), which was released to a more mixed reception than Batman Returns, but was a significant financial success. However, the fourth and final film, Batman & Robin (1997), was a financial and critical failure, regarded as one of the worst blockbuster movies ever made. That film stalled the Batman film series for eight years, until the reboot, Batman Begins (2005).[lower-alpha 41]

By the mid-1990s, Burton and Waters were attached direct a Catwoman-centric film starring Pfeiffer.[213][214] Waters' plot depicted Catwoman as an amnesiac following her injuries at the end of Batman Returns, who ends up in the Las Vegas-like Oasisburg and confronts various publicly virtuous male superheroes who are secretly corrupt. Burton and Pfeiffer took on other projects in the interim until they both lost interest in the project. Warner Bros. eventually developed a separate film, Catwoman (2004), starring Halle Berry in the titular role, which was critically panned and is considered one of the worst comic book films ever made.[215]

Over three decades after the release of Batman Returns, Keaton was scheduled to reprise his version of Batman in Batgirl, a film scheduled for release in 2022, before its cancellation by Warner Bros. parent company, Warner Bros. Discovery.[216][217] Keaton is set to appear as Batman in The Flash (2023).[212][218]

References

Notes

- Although Bob Kane received sole credit for Batman and his associated characters in Batman Returns, it was established in 2015 that writer Bill Finger was jointly involved in the creation of Batman as well as Penguin and Catwoman, among others. He received equal credit to Kane in future adaptations of the Batman comic books.[1][2][3][4]

- The 1992 budget of $50–$90 million is equivalent to $96.5 million–$174 million in 2021.

- The 1992 theatrical box office gross of $266.8 million is equivalent to $515 million in 2021.

- Attributed to multiple references:[15][17][18][19]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][23][24][25]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][26][33][34]

- Attributed to multiple references:[8][25][33][35]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][25][33][38]

- Attributed to multiple references:[8][25][26][43]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][25][44][45]

- Attributed to multiple references:[25][29][41][52]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][25][29][57]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][25][29][47][57]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][25][29][57]

- Attributed to multiple references:[8][9][64][65][66][67]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][24][34][68][69][70][71]

- Attributed to multiple references:[22][77][84][85]

- Attributed to multiple references:[91][96][97][98][99][100][101]

- Attributed to multiple references:[103][104][105][106]

- Attributed to multiple references:[7][70][103][105]

- Attributed to multiple references:[7][12][108][109]

- Attributed to multiple references:[7][12][70][104][111][112]

- Attributed to multiple references:[7][103][104][105][109][111][113]

- Attributed to multiple references:[7][12][70][108]

- Attributed to multiple references:[7][70][104][107][111][105][113]

- Attributed to multiple references:[103][104][105][113]

- Attributed to multiple references:[70][107][109][113][114]

- Attributed to multiple references:[5][26][104][106][115]

- Attributed to multiple references:[5][41][92][96][122][123][124]

- Attributed to multiple references:[5][9][26][125][126]

- Attributed to multiple references:[140][141][142][143]

- Attributed to multiple references:[156][157][158][159][160][161][162][163]

- Attributed to multiple references:[164][165][166][167]

- Attributed to multiple references:[168][169][170][171][172][173][174][175][176][177]

- Attributed to multiple references:[25][111][151][152][183][184][185][186]

- Attributed to multiple references:[183][184][185][186][187][188][189][190][191][192][193]

- Attributed to multiple references:[25][151][194][195][196]

- Attributed to multiple references:[198][199][200][201][202][203][204][205]

- Attributed to multiple references:[196][206][207][208]

- Attributed to multiple references:[8][41][126][210]

- Attributed to multiple references:[125][126][211][212]

Citations

- Meenan, Devin (January 24, 2022). "Batman: Bill Finger's 10 Most Important Contributions To The Character". Vulture. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- Meenan, Devin (January 24, 2022). "Batman's Co-Creator Bill Finger Finally Receives Recognition". Vulture. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- Anders, Charlie Jane (May 8, 2017). "Who Really Created Batman? It Depends What Batman Means To You". Wired. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- Holub, Christian (September 8, 2017). "Batman Co-Creator Bill Finger Finally Will Receive Writing Credit On Gotham, Batman V Superman". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- Mooney, Darren (December 25, 2020). "Have Yourself A Weird, Horny, Lonely Little Christmas With Batman Returns". The Escapist. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- Bastién, Angelica Jade (June 26, 2017). "25 Years Later, Michelle Pfeiffer's Catwoman Is Still the Best Superhero Movie Villain". Vulture. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- Glieberman, Owen (June 26, 1992). "Batman Returns Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- Burton, Byron (June 19, 2017). "Batman Returns At 25: Stars Reveal Script Cuts, Freezing Sets And Aggressive Penguins". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- Nayman, Adam (February 28, 2022). "The Grotesque Beauty Of Batman Returns". The Ringer. Archived from the original on May 3, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- Crow, David; Cecchini, Mike (February 1, 2014). "Alfred: The Many Faces Of Batman's Butler". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on July 27, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- Zachary, Brandon (April 12, 2022). "Batman '89 Turns James Gordon into its Most Tragic Figure". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- Ebert, Roger (June 19, 1992). "Batman Returns". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- Fowler, Matt (March 18, 2009). "Holy Bat OCD!: Batman Returns' Chip Shreck". IGN. Archived from the original on March 18, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- Harris, Mark (June 26, 1992). "What Is Cool 1992: Movies". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- "Batman Returns (1992)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- Cotter, Padraig (November 7, 2021). "Batman Returns: Did The Penguin Murder His Parents Tucker & Esther?". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- Sims, Chris; Uzumeri, David. "Comicsalliance Reviews Batman Returns (1992), Part Two". ComicsAlliance. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- Maslin, Janet (June 19, 1992). "Review/Film: Batman Returns; A Sincere Bat, A Sexy Cat And A Bad Bird". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- Rich, Katey (October 9, 2014). "Saturday Night Live Alum Jan Hooks Dead At 57". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- "Holy Bat OCD!: Batman Returns' Fire Breather". IGN. March 18, 2019. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- Mancuso, Vinnie (October 30, 2020). "Doug Jones Takes Us from Batman Returns Clown To Sexy Fish-Monster To Star Trek Captain". Collider. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- "Batman Returns (1992)". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- Jones 1989, p. 62.

- Weinraub, Bernard (June 22, 1992). "Batman Is Back, And The Money Is Pouring In". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- Crow, David (December 1, 2019). "How Batman II Became Batman Returns". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 17, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- "Batman Returns". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Puig, Claudia (January 10, 1991). "Movies". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- White 1992, p. 8.

- White 1992, p. 10.

- "Batman Returns (1992)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- Welkos, Robert W. (March 27, 1992). "2 Producers Of Batman Sue Warner : Entertainment: They Challenge The Contention That The Film Lost Money. The Studio Says It Observed The Contract". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- Shapiro 1992, p. 32.

- Reilly, Dan; Murthi, Vikram (April 27, 2022). "The Hardest Sequel I Ever Wrote The Writers Behind Blade Runner 2049, Batman Returns, The John Wick Sequels, And More On Their Toughest Franchise Gigs". Vulture. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- Sharkey, Betsy (June 14, 1992). "Film; Batman's City Gets A New Dose Of Urban Blight". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- Shapiro 1992, p. 62.

- Wright, Ridley (December 14, 2021). "Batman Returns: Does Catwoman Really Have Nine Lives?". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- Fischer, William (June 24, 2022). "Batman Returns Shows Tim Burton's Love For Federico Fellini". Collider. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- Shapiro 1992, p. 30.

- White 1992, p. 9.

- Rausch, Andrew J. (May 19, 2021). "Screenwriter Wesley Strick Discusses Mike Nichols' 1994 Film Wolf". Diabolique Magazine. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- "Batman 3". Entertainment Weekly. October 1, 1993. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- Marshall, Rick. "Did Marlon Brando Almost Play The Penguin In Batman Returns? Not Exactly, Says Tim Burton". MTV. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2017.