Caesium

Caesium (IUPAC spelling[6]) (or cesium in American English)[note 1] is a chemical element with the symbol Cs and atomic number 55. It is a soft, silvery-golden alkali metal with a melting point of 28.5 °C (83.3 °F), which makes it one of only five elemental metals that are liquid at or near room temperature.[note 2] Caesium has physical and chemical properties similar to those of rubidium and potassium. It is pyrophoric and reacts with water even at −116 °C (−177 °F). It is the least electronegative element, with a value of 0.79 on the Pauling scale. It has only one stable isotope, caesium-133. Caesium is mined mostly from pollucite. The element has 40 known isotopes, making it, along with barium and mercury, one of the elements with the most isotopes.[11] Caesium-137, a fission product, is extracted from waste produced by nuclear reactors.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caesium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈsiːziəm/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative name | cesium (US) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | pale gold | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Cs) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caesium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 55 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 1: hydrogen and alkali metals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 6s1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 18, 8, 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 301.7 K (28.5 °C, 83.3 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 944 K (671 °C, 1240 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 1.93 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 1.843 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 1938 K, 9.4 MPa[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.09 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 63.9 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 32.210 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1, +1[3] (a strongly basic oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.79 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 265 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 244±11 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 343 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centred cubic (bcc) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 97 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 35.9 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 205 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 1.7 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 1.6 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 0.14 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-46-2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | from Latin caesius, sky blue, for its spectral colours | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff (1860) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Carl Setterberg (1882) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of caesium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The German chemist Robert Bunsen and physicist Gustav Kirchhoff discovered caesium in 1860 by the newly developed method of flame spectroscopy. The first small-scale applications for caesium were as a "getter" in vacuum tubes and in photoelectric cells. In 1967, acting on Einstein's proof that the speed of light is the most constant dimension in the universe, the International System of Units used two specific wave counts from an emission spectrum of caesium-133 to co-define the second and the metre. Since then, caesium has been widely used in highly accurate atomic clocks.

Since the 1990s, the largest application of the element has been as caesium formate for drilling fluids, but it has a range of applications in the production of electricity, in electronics, and in chemistry. The radioactive isotope caesium-137 has a half-life of about 30 years and is used in medical applications, industrial gauges, and hydrology. Nonradioactive caesium compounds are only mildly toxic, but the pure metal's tendency to react explosively with water means that caesium is considered a hazardous material, and the radioisotopes present a significant health and ecological hazard in the environment.

Characteristics

Physical properties

Of all elements that are solid at room temperature, caesium is the softest: it has a hardness of 0.2 Mohs. It is a very ductile, pale metal, which darkens in the presence of trace amounts of oxygen.[12][13][14] When in the presence of mineral oil (where it is best kept during transport), it loses its metallic lustre and takes on a duller, grey appearance. It has a melting point of 28.5 °C (83.3 °F), making it one of the few elemental metals that are liquid near room temperature. Mercury is the only stable elemental metal with a known melting point lower than caesium.[note 3][16] In addition, the metal has a rather low boiling point, 641 °C (1,186 °F), the lowest of all metals other than mercury.[17] Its compounds burn with a blue[18][19] or violet[19] colour.

Caesium forms alloys with the other alkali metals, gold, and mercury (amalgams). At temperatures below 650 °C (1,202 °F), it does not alloy with cobalt, iron, molybdenum, nickel, platinum, tantalum, or tungsten. It forms well-defined intermetallic compounds with antimony, gallium, indium, and thorium, which are photosensitive.[12] It mixes with all the other alkali metals (except lithium); the alloy with a molar distribution of 41% caesium, 47% potassium, and 12% sodium has the lowest melting point of any known metal alloy, at −78 °C (−108 °F).[16][20] A few amalgams have been studied: CsHg

2 is black with a purple metallic lustre, while CsHg is golden-coloured, also with a metallic lustre.[21]

The golden colour of caesium comes from the decreasing frequency of light required to excite electrons of the alkali metals as the group is descended. For lithium through rubidium this frequency is in the ultraviolet, but for caesium it enters the blue–violet end of the spectrum; in other words, the plasmonic frequency of the alkali metals becomes lower from lithium to caesium. Thus caesium transmits and partially absorbs violet light preferentially while other colours (having lower frequency) are reflected; hence it appears yellowish.[22]

Chemical properties

Caesium metal is highly reactive and very pyrophoric. It ignites spontaneously in air, and reacts explosively with water even at low temperatures, more so than the other alkali metals (first group of the periodic table).[12] It reacts with ice at temperatures as low as −116 °C (−177 °F).[16] Because of this high reactivity, caesium metal is classified as a hazardous material. It is stored and shipped in dry, saturated hydrocarbons such as mineral oil. It can be handled only under inert gas, such as argon. However, a caesium-water explosion is often less powerful than a sodium-water explosion with a similar amount of sodium. This is because caesium explodes instantly upon contact with water, leaving little time for hydrogen to accumulate.[23] Caesium can be stored in vacuum-sealed borosilicate glass ampoules. In quantities of more than about 100 grams (3.5 oz), caesium is shipped in hermetically sealed, stainless steel containers.[12]

The chemistry of caesium is similar to that of other alkali metals, in particular rubidium, the element above caesium in the periodic table.[24] As expected for an alkali metal, the only common oxidation state is +1.[note 4] Some slight differences arise from the fact that it has a higher atomic mass and is more electropositive than other (nonradioactive) alkali metals.[26] Caesium is the most electropositive chemical element.[note 5][16] The caesium ion is also larger and less "hard" than those of the lighter alkali metals.

Compounds

Most caesium compounds contain the element as the cation Cs+

, which binds ionically to a wide variety of anions. One noteworthy exception is the caeside anion (Cs−

),[3] and others are the several suboxides (see section on oxides below). More recently, caesium is predicted to behave as a p-block element and capable of forming higher fluorides with higher oxidation states (i.e., CsFn with n > 1) under high pressure.[28] This prediction needs to be validated by further experiments.[29]

Salts of Cs+ are usually colourless unless the anion itself is coloured. Many of the simple salts are hygroscopic, but less so than the corresponding salts of lighter alkali metals. The phosphate,[30] acetate, carbonate, halides, oxide, nitrate, and sulfate salts are water-soluble. Double salts are often less soluble, and the low solubility of caesium aluminium sulfate is exploited in refining Cs from ores. The double salt with antimony (such as CsSbCl

4), bismuth, cadmium, copper, iron, and lead are also poorly soluble.[12]

Caesium hydroxide (CsOH) is hygroscopic and strongly basic.[24] It rapidly etches the surface of semiconductors such as silicon.[31] CsOH has been previously regarded by chemists as the "strongest base", reflecting the relatively weak attraction between the large Cs+ ion and OH−;[18] it is indeed the strongest Arrhenius base; however, a number of compounds such as n-butyllithium, sodium amide, sodium hydride, caesium hydride, etc., which cannot be dissolved in water as reacting violently with it but rather only used in some anhydrous polar aprotic solvents, are far more basic on the basis of the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory.[24]

A stoichiometric mixture of caesium and gold will react to form yellow caesium auride (Cs+Au−) upon heating. The auride anion here behaves as a pseudohalogen. The compound reacts violently with water, yielding caesium hydroxide, metallic gold, and hydrogen gas; in liquid ammonia it can be reacted with a caesium-specific ion exchange resin to produce tetramethylammonium auride. The analogous platinum compound, red caesium platinide (Cs2Pt), contains the platinide ion that behaves as a pseudochalcogen.[32]

Complexes

Like all metal cations, Cs+ forms complexes with Lewis bases in solution. Because of its large size, Cs+ usually adopts coordination numbers greater than 6, the number typical for the smaller alkali metal cations. This difference is apparent in the 8-coordination of CsCl. This high coordination number and softness (tendency to form covalent bonds) are properties exploited in separating Cs+ from other cations in the remediation of nuclear wastes, where 137Cs+ must be separated from large amounts of nonradioactive K+.[33]

Halides

Caesium fluoride (CsF) is a hygroscopic white solid that is widely used in organofluorine chemistry as a source of fluoride anions.[35] Caesium fluoride has the halite structure, which means that the Cs+ and F− pack in a cubic closest packed array as do Na+ and Cl− in sodium chloride.[24] Notably, caesium and fluorine have the lowest and highest electronegativities, respectively, among all the known elements.

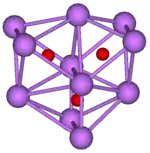

Caesium chloride (CsCl) crystallizes in the simple cubic crystal system. Also called the "caesium chloride structure",[26] this structural motif is composed of a primitive cubic lattice with a two-atom basis, each with an eightfold coordination; the chloride atoms lie upon the lattice points at the edges of the cube, while the caesium atoms lie in the holes in the centre of the cubes. This structure is shared with CsBr and CsI, and many other compounds that do not contain Cs. In contrast, most other alkaline halides have the sodium chloride (NaCl) structure.[26] The CsCl structure is preferred because Cs+ has an ionic radius of 174 pm and Cl−

181 pm.[36]

Oxides

11O

3 cluster

More so than the other alkali metals, caesium forms numerous binary compounds with oxygen. When caesium burns in air, the superoxide CsO

2 is the main product.[37] The "normal" caesium oxide (Cs

2O) forms yellow-orange hexagonal crystals,[38] and is the only oxide of the anti-CdCl

2 type.[39] It vaporizes at 250 °C (482 °F), and decomposes to caesium metal and the peroxide Cs

2O

2 at temperatures above 400 °C (752 °F). In addition to the superoxide and the ozonide CsO

3,[40][41] several brightly coloured suboxides have also been studied.[42] These include Cs

7O, Cs

4O, Cs

11O

3, Cs

3O (dark-green[43]), CsO, Cs

3O

2,[44] as well as Cs

7O

2.[45][46] The latter may be heated in a vacuum to generate Cs

2O.[39] Binary compounds with sulfur, selenium, and tellurium also exist.[12]

Isotopes

Caesium has 40 known isotopes, ranging in mass number (i.e. number of nucleons in the nucleus) from 112 to 151. Several of these are synthesized from lighter elements by the slow neutron capture process (S-process) inside old stars[47] and by the R-process in supernova explosions.[48] The only stable caesium isotope is 133Cs, with 78 neutrons. Although it has a large nuclear spin (7/2+), nuclear magnetic resonance studies can use this isotope at a resonating frequency of 11.7 MHz.[49]

The radioactive 135Cs has a very long half-life of about 2.3 million years, the longest of all radioactive isotopes of caesium. 137Cs and 134Cs have half-lives of 30 and two years, respectively. 137Cs decomposes to a short-lived 137mBa by beta decay, and then to nonradioactive barium, while 134Cs transforms into 134Ba directly. The isotopes with mass numbers of 129, 131, 132 and 136, have half-lives between a day and two weeks, while most of the other isotopes have half-lives from a few seconds to fractions of a second. At least 21 metastable nuclear isomers exist. Other than 134mCs (with a half-life of just under 3 hours), all are very unstable and decay with half-lives of a few minutes or less.[50][51]

The isotope 135Cs is one of the long-lived fission products of uranium produced in nuclear reactors.[52] However, this fission product yield is reduced in most reactors because the predecessor, 135Xe, is a potent neutron poison and frequently transmutes to stable 136Xe before it can decay to 135Cs.[53][54]

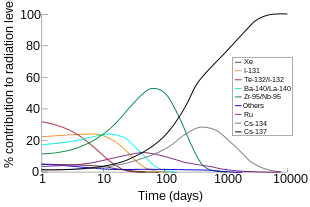

The beta decay from 137Cs to 137mBa is a strong emission of gamma radiation.[55] 137Cs and 90Sr are the principal medium-lived products of nuclear fission, and the prime sources of radioactivity from spent nuclear fuel after several years of cooling, lasting several hundred years.[56] Those two isotopes are the largest source of residual radioactivity in the area of the Chernobyl disaster.[57] Because of the low capture rate, disposing of 137Cs through neutron capture is not feasible and the only current solution is to allow it to decay over time.[58]

Almost all caesium produced from nuclear fission comes from the beta decay of originally more neutron-rich fission products, passing through various isotopes of iodine and xenon.[59] Because iodine and xenon are volatile and can diffuse through nuclear fuel or air, radioactive caesium is often created far from the original site of fission.[60] With nuclear weapons testing in the 1950s through the 1980s, 137Cs was released into the atmosphere and returned to the surface of the earth as a component of radioactive fallout. It is a ready marker of the movement of soil and sediment from those times.[12]

Occurrence

Caesium is a relatively rare element, estimated to average 3 parts per million in the Earth's crust.[61] It is the 45th most abundant element and the 36th among the metals. Nevertheless, it is more abundant than such elements as antimony, cadmium, tin, and tungsten, and two orders of magnitude more abundant than mercury and silver; it is 3.3% as abundant as rubidium, with which it is closely associated, chemically.[12]

Due to its large ionic radius, caesium is one of the "incompatible elements".[62] During magma crystallization, caesium is concentrated in the liquid phase and crystallizes last. Therefore, the largest deposits of caesium are zone pegmatite ore bodies formed by this enrichment process. Because caesium does not substitute for potassium as readily as rubidium does, the alkali evaporite minerals sylvite (KCl) and carnallite (KMgCl

3·6H

2O) may contain only 0.002% caesium. Consequently, caesium is found in few minerals. Percentage amounts of caesium may be found in beryl (Be

3Al

2(SiO

3)

6) and avogadrite ((K,Cs)BF

4), up to 15 wt% Cs2O in the closely related mineral pezzottaite (Cs(Be

2Li)Al

2Si

6O

18), up to 8.4 wt% Cs2O in the rare mineral londonite ((Cs,K)Al

4Be

4(B,Be)

12O

28), and less in the more widespread rhodizite.[12] The only economically important ore for caesium is pollucite Cs(AlSi

2O

6), which is found in a few places around the world in zoned pegmatites, associated with the more commercially important lithium minerals, lepidolite and petalite. Within the pegmatites, the large grain size and the strong separation of the minerals results in high-grade ore for mining.[63]

The world's most significant and richest known source of caesium is the Tanco Mine at Bernic Lake in Manitoba, Canada, estimated to contain 350,000 metric tons of pollucite ore, representing more than two-thirds of the world's reserve base.[63][64] Although the stoichiometric content of caesium in pollucite is 42.6%, pure pollucite samples from this deposit contain only about 34% caesium, while the average content is 24 wt%.[64] Commercial pollucite contains more than 19% caesium.[65] The Bikita pegmatite deposit in Zimbabwe is mined for its petalite, but it also contains a significant amount of pollucite. Another notable source of pollucite is in the Karibib Desert, Namibia.[64] At the present rate of world mine production of 5 to 10 metric tons per year, reserves will last for thousands of years.[12]

Production

Mining and refining pollucite ore is a selective process and is conducted on a smaller scale than for most other metals. The ore is crushed, hand-sorted, but not usually concentrated, and then ground. Caesium is then extracted from pollucite primarily by three methods: acid digestion, alkaline decomposition, and direct reduction.[12][66]

In the acid digestion, the silicate pollucite rock is dissolved with strong acids, such as hydrochloric (HCl), sulfuric (H

2SO

4), hydrobromic (HBr), or hydrofluoric (HF) acids. With hydrochloric acid, a mixture of soluble chlorides is produced, and the insoluble chloride double salts of caesium are precipitated as caesium antimony chloride (Cs

4SbCl

7), caesium iodine chloride (Cs

2ICl), or caesium hexachlorocerate (Cs

2(CeCl

6)). After separation, the pure precipitated double salt is decomposed, and pure CsCl is precipitated by evaporating the water.

The sulfuric acid method yields the insoluble double salt directly as caesium alum (CsAl(SO

4)

2·12H

2O). The aluminium sulfate component is converted to insoluble aluminium oxide by roasting the alum with carbon, and the resulting product is leached with water to yield a Cs

2SO

4 solution.[12]

Roasting pollucite with calcium carbonate and calcium chloride yields insoluble calcium silicates and soluble caesium chloride. Leaching with water or dilute ammonia (NH

4OH) yields a dilute chloride (CsCl) solution. This solution can be evaporated to produce caesium chloride or transformed into caesium alum or caesium carbonate. Though not commercially feasible, the ore can be directly reduced with potassium, sodium, or calcium in vacuum to produce caesium metal directly.[12]

Most of the mined caesium (as salts) is directly converted into caesium formate (HCOO−Cs+) for applications such as oil drilling. To supply the developing market, Cabot Corporation built a production plant in 1997 at the Tanco mine near Bernic Lake in Manitoba, with a capacity of 12,000 barrels (1,900 m3) per year of caesium formate solution.[67] The primary smaller-scale commercial compounds of caesium are caesium chloride and nitrate.[68]

Alternatively, caesium metal may be obtained from the purified compounds derived from the ore. Caesium chloride and the other caesium halides can be reduced at 700 to 800 °C (1,292 to 1,472 °F) with calcium or barium, and caesium metal distilled from the result. In the same way, the aluminate, carbonate, or hydroxide may be reduced by magnesium.[12]

The metal can also be isolated by electrolysis of fused caesium cyanide (CsCN). Exceptionally pure and gas-free caesium can be produced by 390 °C (734 °F) thermal decomposition of caesium azide CsN

3, which can be produced from aqueous caesium sulfate and barium azide.[66] In vacuum applications, caesium dichromate can be reacted with zirconium to produce pure caesium metal without other gaseous products.[68]

- Cs

2Cr

2O

7 + 2 Zr → 2 Cs + 2 ZrO

2+ Cr

2O

3

The price of 99.8% pure caesium (metal basis) in 2009 was about $10 per gram ($280/oz), but the compounds are significantly cheaper.[64]

History

In 1860, Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff discovered caesium in the mineral water from Dürkheim, Germany. Because of the bright blue lines in the emission spectrum, they derived the name from the Latin word caesius, meaning sky-blue.[note 6][69][70][71] Caesium was the first element to be discovered with a spectroscope, which had been invented by Bunsen and Kirchhoff only a year previously.[16]

To obtain a pure sample of caesium, 44,000 litres (9,700 imp gal; 12,000 US gal) of mineral water had to be evaporated to yield 240 kilograms (530 lb) of concentrated salt solution. The alkaline earth metals were precipitated either as sulfates or oxalates, leaving the alkali metal in the solution. After conversion to the nitrates and extraction with ethanol, a sodium-free mixture was obtained. From this mixture, the lithium was precipitated by ammonium carbonate. Potassium, rubidium, and caesium form insoluble salts with chloroplatinic acid, but these salts show a slight difference in solubility in hot water, and the less-soluble caesium and rubidium hexachloroplatinate ((Cs,Rb)2PtCl6) were obtained by fractional crystallization. After reduction of the hexachloroplatinate with hydrogen, caesium and rubidium were separated by the difference in solubility of their carbonates in alcohol. The process yielded 9.2 grams (0.32 oz) of rubidium chloride and 7.3 grams (0.26 oz) of caesium chloride from the initial 44,000 litres of mineral water.[70]

From the caesium chloride, the two scientists estimated the atomic weight of the new element at 123.35 (compared to the currently accepted one of 132.9).[70] They tried to generate elemental caesium by electrolysis of molten caesium chloride, but instead of a metal, they obtained a blue homogeneous substance which "neither under the naked eye nor under the microscope showed the slightest trace of metallic substance"; as a result, they assigned it as a subchloride (Cs

2Cl). In reality, the product was probably a colloidal mixture of the metal and caesium chloride.[72] The electrolysis of the aqueous solution of chloride with a mercury cathode produced a caesium amalgam which readily decomposed under the aqueous conditions.[70] The pure metal was eventually isolated by the German chemist Carl Setterberg while working on his doctorate with Kekulé and Bunsen.[71] In 1882, he produced caesium metal by electrolysing caesium cyanide, avoiding the problems with the chloride.[73]

Historically, the most important use for caesium has been in research and development, primarily in chemical and electrical fields. Very few applications existed for caesium until the 1920s, when it came into use in radio vacuum tubes, where it had two functions; as a getter, it removed excess oxygen after manufacture, and as a coating on the heated cathode, it increased the electrical conductivity. Caesium was not recognized as a high-performance industrial metal until the 1950s.[74] Applications for nonradioactive caesium included photoelectric cells, photomultiplier tubes, optical components of infrared spectrophotometers, catalysts for several organic reactions, crystals for scintillation counters, and in magnetohydrodynamic power generators.[12] Caesium is also used as a source of positive ions in secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS).

Since 1967, the International System of Measurements has based the primary unit of time, the second, on the properties of caesium. The International System of Units (SI) defines the second as the duration of 9,192,631,770 cycles at the microwave frequency of the spectral line corresponding to the transition between two hyperfine energy levels of the ground state of caesium-133.[75] The 13th General Conference on Weights and Measures of 1967 defined a second as: "the duration of 9,192,631,770 cycles of microwave light absorbed or emitted by the hyperfine transition of caesium-133 atoms in their ground state undisturbed by external fields".

Applications

Petroleum exploration

The largest present-day use of nonradioactive caesium is in caesium formate drilling fluids for the extractive oil industry.[12] Aqueous solutions of caesium formate (HCOO−Cs+)—made by reacting caesium hydroxide with formic acid—were developed in the mid-1990s for use as oil well drilling and completion fluids. The function of a drilling fluid is to lubricate drill bits, to bring rock cuttings to the surface, and to maintain pressure on the formation during drilling of the well. Completion fluids assist the emplacement of control hardware after drilling but prior to production by maintaining the pressure.[12]

The high density of the caesium formate brine (up to 2.3 g/cm3, or 19.2 pounds per gallon),[76] coupled with the relatively benign nature of most caesium compounds, reduces the requirement for toxic high-density suspended solids in the drilling fluid—a significant technological, engineering and environmental advantage. Unlike the components of many other heavy liquids, caesium formate is relatively environment-friendly.[76] Caesium formate brine can be blended with potassium and sodium formates to decrease the density of the fluids to that of water (1.0 g/cm3, or 8.3 pounds per gallon). Furthermore, it is biodegradable and may be recycled, which is important in view of its high cost (about $4,000 per barrel in 2001).[77] Alkali formates are safe to handle and do not damage the producing formation or downhole metals as corrosive alternative, high-density brines (such as zinc bromide ZnBr

2 solutions) sometimes do; they also require less cleanup and reduce disposal costs.[12]

Atomic clocks

Caesium-based atomic clocks use the electromagnetic transitions in the hyperfine structure of caesium-133 atoms as a reference point. The first accurate caesium clock was built by Louis Essen in 1955 at the National Physical Laboratory in the UK.[78] Caesium clocks have improved over the past half-century and are regarded as "the most accurate realization of a unit that mankind has yet achieved."[75] These clocks measure frequency with an error of 2 to 3 parts in 1014, which corresponds to an accuracy of 2 nanoseconds per day, or one second in 1.4 million years. The latest versions are more accurate than 1 part in 1015, about 1 second in 20 million years.[12] The caesium standard is the primary standard for standards-compliant time and frequency measurements.[79] Caesium clocks regulate the timing of cell phone networks and the Internet.[80]

Definition of the second

The second, symbol s, is the SI unit of time. It is defined by taking the fixed numerical value of the caesium frequency ΔνCs, the unperturbed ground-state hyperfine transition frequency of the caesium-133 atom, to be 9192631770 when expressed in the unit Hz, which is equal to s−1.

Electric power and electronics

Caesium vapour thermionic generators are low-power devices that convert heat energy to electrical energy. In the two-electrode vacuum tube converter, caesium neutralizes the space charge near the cathode and enhances the current flow.[81]

Caesium is also important for its photoemissive properties, converting light to electron flow. It is used in photoelectric cells because caesium-based cathodes, such as the intermetallic compound K

2CsSb, have a low threshold voltage for emission of electrons.[82] The range of photoemissive devices using caesium include optical character recognition devices, photomultiplier tubes, and video camera tubes.[83][84] Nevertheless, germanium, rubidium, selenium, silicon, tellurium, and several other elements can be substituted for caesium in photosensitive materials.[12]

Caesium iodide (CsI), bromide (CsBr) and caesium fluoride (CsF) crystals are employed for scintillators in scintillation counters widely used in mineral exploration and particle physics research to detect gamma and X-ray radiation. Being a heavy element, caesium provides good stopping power with better detection. Caesium compounds may provide a faster response (CsF) and be less hygroscopic (CsI).

Caesium vapour is used in many common magnetometers.[85]

The element is used as an internal standard in spectrophotometry.[86] Like other alkali metals, caesium has a great affinity for oxygen and is used as a "getter" in vacuum tubes.[87] Other uses of the metal include high-energy lasers, vapour glow lamps, and vapour rectifiers.[12]

Centrifugation fluids

The high density of the caesium ion makes solutions of caesium chloride, caesium sulfate, and caesium trifluoroacetate (Cs(O

2CCF

3)) useful in molecular biology for density gradient ultracentrifugation.[88] This technology is used primarily in the isolation of viral particles, subcellular organelles and fractions, and nucleic acids from biological samples.[89]

Chemical and medical use

Relatively few chemical applications use caesium.[90] Doping with caesium compounds enhances the effectiveness of several metal-ion catalysts for chemical synthesis, such as acrylic acid, anthraquinone, ethylene oxide, methanol, phthalic anhydride, styrene, methyl methacrylate monomers, and various olefins. It is also used in the catalytic conversion of sulfur dioxide into sulfur trioxide in the production of sulfuric acid.[12]

Caesium fluoride enjoys a niche use in organic chemistry as a base[24] and as an anhydrous source of fluoride ion.[91] Caesium salts sometimes replace potassium or sodium salts in organic synthesis, such as cyclization, esterification, and polymerization. Caesium has also been used in thermoluminescent radiation dosimetry (TLD): When exposed to radiation, it acquires crystal defects that, when heated, revert with emission of light proportionate to the received dose. Thus, measuring the light pulse with a photomultiplier tube can allow the accumulated radiation dose to be quantified.

Nuclear and isotope applications

Caesium-137 is a radioisotope commonly used as a gamma-emitter in industrial applications. Its advantages include a half-life of roughly 30 years, its availability from the nuclear fuel cycle, and having 137Ba as a stable end product. The high water solubility is a disadvantage which makes it incompatible with large pool irradiators for food and medical supplies.[92] It has been used in agriculture, cancer treatment, and the sterilization of food, sewage sludge, and surgical equipment.[12][93] Radioactive isotopes of caesium in radiation devices were used in the medical field to treat certain types of cancer,[94] but emergence of better alternatives and the use of water-soluble caesium chloride in the sources, which could create wide-ranging contamination, gradually put some of these caesium sources out of use.[95][96] Caesium-137 has been employed in a variety of industrial measurement gauges, including moisture, density, levelling, and thickness gauges.[97] It has also been used in well logging devices for measuring the electron density of the rock formations, which is analogous to the bulk density of the formations.[98]

Caesium-137 has been used in hydrologic studies analogous to those with tritium. As a daughter product of fission bomb testing from the 1950s through the mid-1980s, caesium-137 was released into the atmosphere, where it was absorbed readily into solution. Known year-to-year variation within that period allows correlation with soil and sediment layers. Caesium-134, and to a lesser extent caesium-135, have also been used in hydrology to measure the caesium output by the nuclear power industry. While they are less prevalent than either caesium-133 or caesium-137, these bellwether isotopes are produced solely from anthropogenic sources.[99]

Other uses

Caesium and mercury were used as a propellant in early ion engines designed for spacecraft propulsion on very long interplanetary or extraplanetary missions. The fuel was ionized by contact with a charged tungsten electrode. But corrosion by caesium on spacecraft components has pushed development in the direction of inert gas propellants, such as xenon, which are easier to handle in ground-based tests and do less potential damage to the spacecraft.[12] Xenon was used in the experimental spacecraft Deep Space 1 launched in 1998.[100][101] Nevertheless, field-emission electric propulsion thrusters that accelerate liquid metal ions such as caesium have been built.[102]

Caesium nitrate is used as an oxidizer and pyrotechnic colorant to burn silicon in infrared flares,[103] such as the LUU-19 flare,[104] because it emits much of its light in the near infrared spectrum.[105] Caesium compounds may have been used as fuel additives to reduce the radar signature of exhaust plumes in the Lockheed A-12 CIA reconnaissance aircraft.[106] Caesium and rubidium have been added as a carbonate to glass because they reduce electrical conductivity and improve stability and durability of fibre optics and night vision devices. Caesium fluoride or caesium aluminium fluoride are used in fluxes formulated for brazing aluminium alloys that contain magnesium.[12]

Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) power-generating systems were researched, but failed to gain widespread acceptance.[107] Caesium metal has also been considered as the working fluid in high-temperature Rankine cycle turboelectric generators.[108]

Caesium salts have been evaluated as antishock reagents following the administration of arsenical drugs. Because of their effect on heart rhythms, however, they are less likely to be used than potassium or rubidium salts. They have also been used to treat epilepsy.[12]

Caesium-133 can be laser cooled and used to probe fundamental and technological problems in quantum physics. It has a particularly convenient Feshbach spectrum to enable studies of ultracold atoms requiring tunable interactions.[109]

Health and safety hazards

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling:[110] | |

Pictograms |

|

Signal word |

Danger |

Hazard statements |

H260, H314 |

Precautionary statements |

P223, P231+P232, P280, P305+P351+P338, P370+P378, P422 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Nonradioactive caesium compounds are only mildly toxic, and nonradioactive caesium is not a significant environmental hazard. Because biochemical processes can confuse and substitute caesium with potassium, excess caesium can lead to hypokalemia, arrhythmia, and acute cardiac arrest, but such amounts would not ordinarily be encountered in natural sources.[112][113]

The median lethal dose (LD50) for caesium chloride in mice is 2.3 g per kilogram, which is comparable to the LD50 values of potassium chloride and sodium chloride.[114] The principal use of nonradioactive caesium is as caesium formate in petroleum drilling fluids because it is much less toxic than alternatives, though it is more costly.[76]

Caesium metal is one of the most reactive elements and is highly explosive in the presence of water. The hydrogen gas produced by the reaction is heated by the thermal energy released at the same time, causing ignition and a violent explosion. This can occur with other alkali metals, but caesium is so potent that this explosive reaction can be triggered even by cold water.[12]

It is highly pyrophoric: the autoignition temperature of caesium is −116 °C (−177 °F), and it ignites explosively in air to form caesium hydroxide and various oxides. Caesium hydroxide is a very strong base, and will rapidly corrode glass.[17]

The isotopes 134 and 137 are present in the biosphere in small amounts from human activities, differing by location. Radiocaesium does not accumulate in the body as readily as other fission products (such as radioiodine and radiostrontium). About 10% of absorbed radiocaesium washes out of the body relatively quickly in sweat and urine. The remaining 90% has a biological half-life between 50 and 150 days.[115] Radiocaesium follows potassium and tends to accumulate in plant tissues, including fruits and vegetables.[116][117][118] Plants vary widely in the absorption of caesium, sometimes displaying great resistance to it. It is also well-documented that mushrooms from contaminated forests accumulate radiocaesium (caesium-137) in the fungal sporocarps.[119] Accumulation of caesium-137 in lakes has been a great concern after the Chernobyl disaster.[120][121] Experiments with dogs showed that a single dose of 3.8 millicuries (140 MBq, 4.1 μg of caesium-137) per kilogram is lethal within three weeks;[122] smaller amounts may cause infertility and cancer.[123] The International Atomic Energy Agency and other sources have warned that radioactive materials, such as caesium-137, could be used in radiological dispersion devices, or "dirty bombs".[124]

See also

- Goiânia accident, a major radioactive contamination incident in 1987 involving Caesium-137.

- Kramatorsk radiological accident, another 137Cs incident between 1980 and 1989.

- Acerinox accident, a Caesium-137 contamination accident in 1998.

Notes

- Caesium is the spelling recommended by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).[7] The American Chemical Society (ACS) has used the spelling cesium since 1921,[8][9] following Webster's New International Dictionary. The element was named after the Latin word caesius, meaning "bluish grey".[10] In medieval and early modern writings caesius was spelled with the ligature æ as cæsius; hence, an alternative but now old-fashioned orthography is cæsium. More spelling explanation at ae/oe vs e.

- Along with rubidium (39 °C [102 °F]), francium (estimated at 27 °C [81 °F]), mercury (−39 °C [−38 °F]), and gallium (30 °C [86 °F]); bromine is also liquid at room temperature (melting at −7.2 °C [19.0 °F]), but it is a halogen and not a metal. Preliminary work with copernicium and flerovium suggests that they are gaseous metals at room temperature.

- The radioactive element francium may also have a lower melting point, but its radioactivity prevents enough of it from being isolated for direct testing.[15] Copernicium and flerovium may also have lower melting points.

- It differs from this value in caesides, which contain the Cs− anion and thus have caesium in the −1 oxidation state.[3] Additionally, 2013 calculations by Mao-sheng Miao indicate that under conditions of extreme pressure (greater than 30 GPa), the inner 5p electrons could form chemical bonds, where caesium would behave as the seventh 5p element. This discovery indicates that higher caesium fluorides with caesium in oxidation states from +2 to +6 could exist under such conditions.[25]

- Francium's electropositivity has not been experimentally measured due to its high radioactivity. Measurements of the first ionization energy of francium suggest that its relativistic effects may lower its reactivity and raise its electronegativity above that expected from periodic trends.[27]

- Bunsen quotes Aulus Gellius Noctes Atticae II, 26 by Nigidius Figulus: Nostris autem veteribus caesia dicts est quae Graecis, ut Nigidus ait, de colore coeli quasi coelia.

References

- "Standard Atomic Weights: Caesium". CIAAW. 2013.

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.121. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- Dye, J. L. (1979). "Compounds of Alkali Metal Anions". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 18 (8): 587–598. doi:10.1002/anie.197905871.

- "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (87th ed.). CRC press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- "NIST Radionuclide Half-Life Measurements". NIST. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- "IUPAC Periodic Table of Elements". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2005). Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 2005). Cambridge (UK): RSC–IUPAC. ISBN 0-85404-438-8. pp. 248–49. Electronic version..

- Coghill, Anne M.; Garson, Lorrin R., eds. (2006). The ACS Style Guide: Effective Communication of Scientific Information (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8412-3999-9.

- Coplen, T. B.; Peiser, H. S. (1998). "History of the recommended atomic-weight values from 1882 to 1997: a comparison of differences from current values to the estimated uncertainties of earlier values" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 70 (1): 237–257. doi:10.1351/pac199870010237. S2CID 96729044.

- OED entry for "caesium". Second edition, 1989; online version June 2012. Retrieved 07 September 2012. Earlier version first published in New English Dictionary, 1888.

- "Isotopes". Ptable.

- Butterman, William C.; Brooks, William E.; Reese, Robert G. Jr. (2004). "Mineral Commodity Profile: Cesium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2007. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- Heiserman, David L. (1992). Exploring Chemical Elements and their Compounds. McGraw-Hill. pp. 201–203. ISBN 978-0-8306-3015-8.

- Addison, C. C. (1984). The Chemistry of the Liquid Alkali Metals. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-90508-0. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- "Francium". Periodic.lanl.gov. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- Kaner, Richard (2003). "C&EN: It's Elemental: The Periodic Table – Cesium". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- "Chemical Data – Caesium – Cs". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- Lynch, Charles T. (1974). CRC Handbook of Materials Science. CRC Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8493-2321-8.

- Clark, Jim (2005). "Flame Tests". chemguide. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- Taova, T. M.; et al. (June 22, 2003). "Density of melts of alkali metals and their Na-K-Cs and Na-K-Rb ternary systems" (PDF). Fifteenth symposium on thermophysical properties, Boulder, Colorado, United States. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2006. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- Deiseroth, H. J. (1997). "Alkali metal amalgams, a group of unusual alloys". Progress in Solid State Chemistry. 25 (1–2): 73–123. doi:10.1016/S0079-6786(97)81004-7.

- Addison, C. C. (1984). The chemistry of the liquid alkali metals. Wiley. p. 7. ISBN 9780471905080.

- Gray, Theodore (2012) The Elements, Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, p. 131, ISBN 1-57912-895-5.

- Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4.

- Moskowitz, Clara. "A Basic Rule of Chemistry Can Be Broken, Calculations Show". Scientific American. Retrieved 2013-11-22.

- Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Vergleichende Übersicht über die Gruppe der Alkalimetalle". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 953–955. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- Andreev, S. V.; Letokhov, V. S.; Mishin, V. I. (1987). "Laser resonance photoionization spectroscopy of Rydberg levels in Fr". Physical Review Letters. 59 (12): 1274–76. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..59.1274A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.1274. PMID 10035190.

- Miao, Mao-sheng (2013). "Caesium in high oxidation states and as a p-block element". Nature Chemistry. 5 (10): 846–852. arXiv:1212.6290. Bibcode:2013NatCh...5..846M. doi:10.1038/nchem.1754. ISSN 1755-4349. PMID 24056341. S2CID 38839337.

- Sneed, D.; Pravica, M.; Kim, E.; Chen, N.; Park, C.; White, M. (2017-10-01). "Forcing Cesium into Higher Oxidation States Using Useful hard x-ray Induced Chemistry under High Pressure". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 950 (11, 2017): 042055. Bibcode:2017JPhCS.950d2055S. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/950/4/042055. ISSN 1742-6588. OSTI 1409108. S2CID 102912809.

- Hogan, C. M. (2011)."Phosphate". Archived from the original on 2012-10-25. Retrieved 2012-06-17. in Encyclopedia of Earth. Jorgensen, A. and Cleveland, C.J. (eds.). National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC

- Köhler, Michael J. (1999). Etching in microsystem technology. Wiley-VCH. p. 90. ISBN 978-3-527-29561-6.

- Jansen, Martin (2005-11-30). "Effects of relativistic motion of electrons on the chemistry of gold and platinum". Solid State Sciences. 7 (12): 1464–1474. Bibcode:2005SSSci...7.1464J. doi:10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2005.06.015.

- Moyer, Bruce A.; Birdwell, Joseph F.; Bonnesen, Peter V.; Delmau, Laetitia H. (2005). Use of Macrocycles in Nuclear-Waste Cleanup: A Realworld Application of a Calixcrown in Cesium Separation Technology. Macrocyclic Chemistry. pp. 383–405. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3687-6_24. ISBN 978-1-4020-3364-3..

- Senga, Ryosuke; Suenaga, Kazu (2015). "Single-atom electron energy loss spectroscopy of light elements". Nature Communications. 6: 7943. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.7943S. doi:10.1038/ncomms8943. PMC 4532884. PMID 26228378.

- Evans, F. W.; Litt, M. H.; Weidler-Kubanek, A. M.; Avonda, F. P. (1968). "Reactions Catalyzed by Potassium Fluoride. 111. The Knoevenagel Reaction". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 33 (5): 1837–1839. doi:10.1021/jo01269a028.

- Wells, A. F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.). Oxford Science Publications. ISBN 978-0-19-855370-0.

- Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, G. (1962). Advanced Inorganic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-471-84997-1.

- Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 451, 514. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- Tsai, Khi-Ruey; Harris, P. M.; Lassettre, E. N. (1956). "The Crystal Structure of Cesium Monoxide". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 60 (3): 338–344. doi:10.1021/j150537a022. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017.

- Vol'nov, I. I.; Matveev, V. V. (1963). "Synthesis of cesium ozonide through cesium superoxide". Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences, USSR Division of Chemical Science. 12 (6): 1040–1043. doi:10.1007/BF00845494.

- Tokareva, S. A. (1971). "Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metal Ozonides". Russian Chemical Reviews. 40 (2): 165–174. Bibcode:1971RuCRv..40..165T. doi:10.1070/RC1971v040n02ABEH001903. S2CID 250883291.

- Simon, A. (1997). "Group 1 and 2 Suboxides and Subnitrides — Metals with Atomic Size Holes and Tunnels". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 163: 253–270. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(97)00013-1.

- Tsai, Khi-Ruey; Harris, P. M.; Lassettre, E. N. (1956). "The Crystal Structure of Tricesium Monoxide". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 60 (3): 345–347. doi:10.1021/j150537a023.

- Okamoto, H. (2009). "Cs-O (Cesium-Oxygen)". Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion. 31: 86–87. doi:10.1007/s11669-009-9636-5. S2CID 96084147.

- Band, A.; Albu-Yaron, A.; Livneh, T.; Cohen, H.; Feldman, Y.; Shimon, L.; Popovitz-Biro, R.; Lyahovitskaya, V.; Tenne, R. (2004). "Characterization of Oxides of Cesium". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 108 (33): 12360–12367. doi:10.1021/jp036432o.

- Brauer, G. (1947). "Untersuchungen ber das System Csium-Sauerstoff". Zeitschrift für Anorganische Chemie. 255 (1–3): 101–124. doi:10.1002/zaac.19472550110.

- Busso, M.; Gallino, R.; Wasserburg, G. J. (1999). "Nucleosynthesis in Asymptotic Giant Branch Stars: Relevance for Galactic Enrichment and Solar System Formation" (PDF). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 37: 239–309. Bibcode:1999ARA&A..37..239B. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.37.1.239. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- Arnett, David (1996). Supernovae and Nucleosynthesis: An Investigation of the History of Matter, from the Big Bang to the Present. Princeton University Press. p. 527. ISBN 978-0-691-01147-9.

- Goff, C.; Matchette, Michael A.; Shabestary, Nahid; Khazaeli, Sadegh (1996). "Complexation of caesium and rubidium cations with crown ethers in N,N-dimethylformamide". Polyhedron. 15 (21): 3897–3903. doi:10.1016/0277-5387(96)00018-6.

- Brown, F.; Hall, G. R.; Walter, A. J. (1955). "The half-life of Cs137". Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 1 (4–5): 241–247. Bibcode:1955PhRv...99..188W. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(55)80027-9.

- Sonzogni, Alejandro. "Interactive Chart of Nuclides". National Nuclear Data Center: Brookhaven National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2008-05-22. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Ohki, Shigeo; Takaki, Naoyuki (14–16 October 2002). Transmutation of Cesium-135 with Fast Reactors (PDF). Seventh Information Exchange Meeting on Actinide and Fission Product Partitioning and Transmutation. Jeju, Korea. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- "20 Xenon: A Fission Product Poison" (PDF). CANDU Fundamentals (Report). CANDU Owners Group Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- Taylor, V. F.; Evans, R. D.; Cornett, R. J. (2008). "Preliminary evaluation of 135Cs/137Cs as a forensic tool for identifying source of radioactive contamination". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 99 (1): 109–118. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2007.07.006. PMID 17869392.

- "Cesium | Radiation Protection". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2006-06-28. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- Zerriffi, Hisham (2000-05-24). IEER Report: Transmutation – Nuclear Alchemy Gamble (Report). Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- Chernobyl's Legacy: Health, Environmental and Socia-Economic Impacts and Recommendations to the Governments of Belarus, Russian Federation and Ukraine (PDF) (Report). International Atomic Energy Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-15. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- Kase, Takeshi; Konashi, Kenji; Takahashi, Hiroshi; Hirao, Yasuo (1993). "Transmutation of Cesium-137 Using Proton Accelerator". Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology. 30 (9): 911–918. doi:10.3327/jnst.30.911.

- Knief, Ronald Allen (1992). "Fission Fragments". Nuclear engineering: theory and technology of commercial nuclear power. Taylor & Francis. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-56032-088-3.

- Ishiwatari, N.; Nagai, H. "Release of xenon-137 and iodine-137 from UO2 pellet by pulse neutron irradiation at NSRR". Nippon Genshiryoku Gakkaishi. 23 (11): 843–850. OSTI 5714707.

- Turekian, K. K.; Wedepohl, K. H. (1961). "Distribution of the elements in some major units of the Earth's crust". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 72 (2): 175–192. Bibcode:1961GSAB...72..175T. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1961)72[175:DOTEIS]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- Rowland, Simon (1998-07-04). "Cesium as a Raw Material: Occurrence and Uses". Artemis Society International. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- Černý, Petr; Simpson, F. M. (1978). "The Tanco Pegmatite at Bernic Lake, Manitoba: X. Pollucite" (PDF). Canadian Mineralogist. 16: 325–333. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- Polyak, Désirée E. "Cesium" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- Norton, J. J. (1973). "Lithium, cesium, and rubidium—The rare alkali metals". In Brobst, D. A.; Pratt, W. P. (eds.). United States mineral resources. Vol. Paper 820. U.S. Geological Survey Professional. pp. 365–378. Archived from the original on 2010-07-21. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- Burt, R. O. (1993). "Caesium and cesium compounds". Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology. Vol. 5 (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 749–764. ISBN 978-0-471-48494-3.

- Benton, William; Turner, Jim (2000). "Cesium formate fluid succeeds in North Sea HPHT field trials" (PDF). Drilling Contractor (May/June): 38–41. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- Eagleson, Mary, ed. (1994). Concise encyclopedia chemistry. Eagleson, Mary. Berlin: de Gruyter. p. 198. ISBN 978-3-11-011451-5.

- Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Edition

- Kirchhoff, G.; Bunsen, R. (1861). "Chemische Analyse durch Spectralbeobachtungen" (PDF). Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 189 (7): 337–381. Bibcode:1861AnP...189..337K. doi:10.1002/andp.18611890702. hdl:2027/hvd.32044080591324.

- Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements. XIII. Some spectroscopic discoveries". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (8): 1413–1434. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9.1413W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1413.

- Zsigmondy, Richard (2007). Colloids and the Ultra Microscope. Read books. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-4067-5938-9.

- Setterberg, Carl (1882). "Ueber die Darstellung von Rubidium- und Cäsiumverbindungen und über die Gewinnung der Metalle selbst". Justus Liebig's Annalen der Chemie. 211: 100–116. doi:10.1002/jlac.18822110105.

- Strod, A. J. (1957). "Cesium—A new industrial metal". American Ceramic Bulletin. 36 (6): 212–213.

- "Cesium Atoms at Work". Time Service Department—U.S. Naval Observatory—Department of the Navy. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- Downs, J. D.; Blaszczynski, M.; Turner, J.; Harris, M. (February 2006). Drilling and Completing Difficult HP/HT Wells With the Aid of Cesium Formate Brines-A Performance Review. IADC/SPE Drilling Conference. Miami, Florida, USASociety of Petroleum Engineers. doi:10.2118/99068-MS. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12.

- Flatern, Rick (2001). "Keeping cool in the HPHT environment". Offshore Engineer (February): 33–37.

- Essen, L.; Parry, J. V. L. (1955). "An Atomic Standard of Frequency and Time Interval: A Caesium Resonator". Nature. 176 (4476): 280–282. Bibcode:1955Natur.176..280E. doi:10.1038/176280a0. S2CID 4191481.

- Markowitz, W.; Hall, R.; Essen, L.; Parry, J. (1958). "Frequency of Cesium in Terms of Ephemeris Time". Physical Review Letters. 1 (3): 105–107. Bibcode:1958PhRvL...1..105M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.1.105.

- Reel, Monte (2003-07-22). "Where timing truly is everything". The Washington Post. p. B1. Archived from the original on 2013-04-29. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- Rasor, Ned S.; Warner, Charles (September 1964). "Correlation of Emission Processes for Adsorbed Alkali Films on Metal Surfaces". Journal of Applied Physics. 35 (9): 2589–2600. Bibcode:1964JAP....35.2589R. doi:10.1063/1.1713806.

- "Cesium Supplier & Technical Information". American Elements. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- Smedley, John; Rao, Triveni; Wang, Erdong (2009). "K2CsSb Cathode Development". AIP Conference Proceedings. 1149 (1): 1062–1066. Bibcode:2009AIPC.1149.1062S. doi:10.1063/1.3215593.

- Görlich, P. (1936). "Über zusammengesetzte, durchsichtige Photokathoden". Zeitschrift für Physik. 101 (5–6): 335–342. Bibcode:1936ZPhy..101..335G. doi:10.1007/BF01342330. S2CID 121613539.

- Groeger, S.; Pazgalev, A. S.; Weis, A. (2005). "Comparison of discharge lamp and laser pumped cesium magnetometers". Applied Physics B. 80 (6): 645–654. arXiv:physics/0412011. Bibcode:2005ApPhB..80..645G. doi:10.1007/s00340-005-1773-x. S2CID 36065775.

- Haven, Mary C.; Tetrault, Gregory A.; Schenken, Jerald R. (1994). "Internal Standards". Laboratory instrumentation. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-471-28572-4.

- McGee, James D. (1969). Photo-electronic image devices: proceedings of the fourth symposium held at Imperial College, London, September 16–20, 1968. Vol. 1. Academic Press. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-12-014528-7.

- Manfred Bick, Horst Prinz, "Cesium and Cesium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_153.

- Desai, Mohamed A., ed. (2000). "Gradient Materials". Downstream processing methods. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-89603-564-5.

- Burt, R. O. (1993). "Cesium and cesium compounds". Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology. Vol. 5 (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 759. ISBN 978-0-471-15158-6.

- Friestad, Gregory K.; Branchaud, Bruce P.; Navarrini, Walter and Sansotera, Maurizio (2007) "Cesium Fluoride" in Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis, John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rc050.pub2

- Okumura, Takeshi (2003-10-21). "The material flow of radioactive cesium-137 in the U.S. 2000" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- Jensen, N. L. (1985). "Cesium". Mineral facts and problems. Vol. Bulletin 675. U.S. Bureau of Mines. pp. 133–138.

- "IsoRay's Cesium-131 Medical Isotope Used In Milestone Procedure Treating Eye Cancers At Tufts-New England Medical Center". Medical News Today. 2007-12-17. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- Bentel, Gunilla Carleson (1996). "Caesium-137 Machines". Radiation therapy planning. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-07-005115-7. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Radiation Source Use and Replacement (2008). Radiation source use and replacement: abbreviated version. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-11014-3.

- Loxton, R.; Pope, P., eds. (1995). "Level and density measurement using non-contact nuclear gauges". Instrumentation : A Reader. London: Chapman & Hall. pp. 82–85. ISBN 978-0-412-53400-3.

- Timur, A.; Toksoz, M. N. (1985). "Downhole Geophysical Logging". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 13: 315–344. Bibcode:1985AREPS..13..315T. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.13.050185.001531.

- Kendall, Carol. "Isotope Tracers Project – Resources on Isotopes – Cesium". National Research Program – U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- Marcucci, M. G.; Polk, J. E. (2000). "NSTAR Xenon Ion Thruster on Deep Space 1: Ground and flight tests (invited)". Review of Scientific Instruments. 71 (3): 1389–1400. Bibcode:2000RScI...71.1389M. doi:10.1063/1.1150468.

- Sovey, James S.; Rawlin, Vincent K.; Patterson, Michael J. "A Synopsis of Ion Propulsion Development Projects in the United States: SERT I to Deep Space I" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 29, 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- Marrese, C.; Polk, J.; Mueller, J.; Owens, A.; Tajmar, M.; Fink, R. & Spindt, C. (October 2001). In-FEEP Thruster Ion Beam Neutralization with Thermionic and Field Emission Cathodes. 27th International Electric Propulsion Conference. Pasadena, California. pp. 1–15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- "Infrared illumination compositions and articles containing the same". United States Patent 6230628. Freepatentsonline.com. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- "LUU-19 Flare". Federation of American Scientists. 2000-04-23. Archived from the original on 2010-08-06. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- Charrier, E.; Charsley, E. L.; Laye, P. G.; Markham, H. M.; Berger, B.; Griffiths, T. T. (2006). "Determination of the temperature and enthalpy of the solid–solid phase transition of caesium nitrate by differential scanning calorimetry". Thermochimica Acta. 445: 36–39. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2006.04.002.

- Crickmore, Paul F. (2000). Lockheed SR-71: the secret missions exposed. Osprey. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-84176-098-8.

- National Research Council (U.S.) (2001). Energy research at DOE—Was it worth it?. National Academy Press. pp. 190–194. doi:10.17226/10165. ISBN 978-0-309-07448-3. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- Roskill Information Services (1984). Economics of Caesium and Rubidium (Reports on Metals & Minerals). London, United Kingdom: Roskill Information Services. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-86214-250-6.

- Chin, Cheng; Grimm, Rudolf; Julienne, Paul; Tiesinga, Eite (2010-04-29). "Feshbach resonances in ultracold gases". Reviews of Modern Physics. 82 (2): 1225–1286. arXiv:0812.1496. Bibcode:2010RvMP...82.1225C. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.82.1225. S2CID 118340314.

- "Cesium 239240". Sigma-Aldrich. 2021-09-17. Retrieved 2021-12-21.

- Data from The Radiochemical Manual and Wilson, B. J. (1966) The Radiochemical Manual (2nd ed.).

- Melnikov, P.; Zanoni, L. Z. (June 2010). "Clinical effects of cesium intake". Biological Trace Element Research. 135 (1–3): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s12011-009-8486-7. PMID 19655100. S2CID 19186683.

- Pinsky, Carl; Bose, Ranjan; Taylor, J. R.; McKee, Jasper; Lapointe, Claude; Birchall, James (1981). "Cesium in mammals: Acute toxicity, organ changes and tissue accumulation". Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A. 16 (5): 549–567. doi:10.1080/10934528109375003.

- Johnson, Garland T.; Lewis, Trent R.; Wagner, D. Wagner (1975). "Acute toxicity of cesium and rubidium compounds". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 32 (2): 239–245. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(75)90216-1. PMID 1154391.

- Rundo, J. (1964). "A Survey of the Metabolism of Caesium in Man". British Journal of Radiology. 37 (434): 108–114. doi:10.1259/0007-1285-37-434-108. PMID 14120787.

- Nishita, H.; Dixon, D.; Larson, K. H. (1962). "Accumulation of Cs and K and growth of bean plants in nutrient solution and soils". Plant and Soil. 17 (2): 221–242. doi:10.1007/BF01376226. S2CID 10293954.

- Avery, S. (1996). "Fate of caesium in the environment: Distribution between the abiotic and biotic components of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 30 (2): 139–171. doi:10.1016/0265-931X(96)89276-9.

- Salbu, Brit; Østby, Georg; Garmo, Torstein H.; Hove, Knut (1992). "Availability of caesium isotopes in vegetation estimated from incubation and extraction experiments". Analyst. 117 (3): 487–491. Bibcode:1992Ana...117..487S. doi:10.1039/AN9921700487. PMID 1580386.

- Vinichuk, M. (2010). "Accumulation of potassium, rubidium and caesium (133Cs and 137Cs) in various fractions of soil and fungi in a Swedish forest". Science of the Total Environment. 408 (12): 2543–2548. Bibcode:2010ScTEn.408.2543V. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.02.024. PMID 20334900.

- Smith, Jim T.; Beresford, Nicholas A. (2005). Chernobyl: Catastrophe and Consequences. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-23866-9.

- Eremeev, V. N.; Chudinovskikh, T. V.; Batrakov, G. F.; Ivanova, T. M. (1991). "Radioactive isotopes of caesium in the waters and near-water atmospheric layer of the Black Sea". Physical Oceanography. 2 (1): 57–64. doi:10.1007/BF02197418. S2CID 127482742.

- Redman, H. C.; McClellan, R. O.; Jones, R. K.; Boecker, B. B.; Chiffelle, T. L.; Pickrell, J. A.; Rypka, E. W. (1972). "Toxicity of 137-CsCl in the Beagle. Early Biological Effects". Radiation Research. 50 (3): 629–648. Bibcode:1972RadR...50..629R. doi:10.2307/3573559. JSTOR 3573559. PMID 5030090.

- "Chinese 'find' radioactive ball". BBC News. 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- Charbonneau, Louis (2003-03-12). "IAEA director warns of 'dirty bomb' risk". The Washington Post. Reuters. p. A15. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

External links

- Caesium or Cesium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- View the reaction of Caesium (most reactive metal in the periodic table) with Fluorine (most reactive non-metal) courtesy of The Royal Institution.

- Rogachev, Andrey Yu.; Miao, Mao-Sheng; Merino, Gabriel; Hoffmann, Roald (2015). "Molecular CsF5and CsF2+". Angewandte Chemie. 127 (28): 8393–8396. Bibcode:2015AngCh.127.8393R. doi:10.1002/ange.201500402.