Geography of the United States

The term 'United States', when used in the geographical sense, refers to the contiguous United States, the state of Alaska, the island state of Hawaii, the five insular territories of Puerto Rico, Northern Mariana Islands, U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and American Samoa, and minor outlying possessions.[1] The United States shares land borders with Canada and Mexico and maritime borders with Russia, Cuba, The Bahamas, and other countries,[note 2] in addition to Canada and Mexico. The northern border of the United States with Canada is the world's longest bi-national land border.

| |

| Continent | North America |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38.000°N 97.000°W |

| Area | Ranked 3rd/4th |

| • Total | 9,826,675 km2 (3,794,100 sq mi) |

| • Land | 93.24% |

| • Water | 6.76% |

| Coastline | 19,920 km (12,380 mi) |

| Borders | Canada: 8,864 km (5,508 mi) Mexico: 3,327 km (2,067 mi) |

| Highest point | Denali 6,190.5 m (20,310 ft) |

| Lowest point | Badwater Basin, −85 m (−279 ft) |

| Longest river | Missouri River, 3,767 km (2,341 mi) |

| Largest lake | Lake Superior 58,000 km2 (22,394 sq mi) |

| Climate | Diverse: Ranges from Temperate in the North to Tropical in the far south. West: mostly semi-arid to desert, Mountains: alpine, Northeast: humid continental, Southeast: humid subtropical, Coast of California: Mediterranean, Pacific Northwest: cool temperate oceanic, Alaska: mostly subarctic, Hawaii, South Florida, and the territories: tropical |

| Terrain | Vast central plain, Interior Highlands and low mountains in Midwest, mountains and valleys in the mid-south, coastal flatland near the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, complete with mangrove forests and temperate, subtropical, and tropical laurel forest and jungle, canyons, basins, plateaus, and mountains in west, hills and low mountains in east; intermittent hilly and mountainous regions in Great Plains, with occasional badland topography; rugged mountains and broad river valleys in Alaska; rugged, volcanic topography in Hawaii and the territories |

| Natural resources | coal, copper, lead, molybdenum, phosphates, rare earth elements, uranium, bauxite, gold, iron, mercury, nickel, potash, silver, tungsten, zinc, petroleum, natural gas, timber, arable land |

| Natural hazards | tsunamis; volcanoes; earthquake activity around Pacific Basin; hurricanes along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts; tornadoes in the Midwest and Southeast; mud slides in California; forest fires in the west; flooding; permafrost in northern Alaska |

| Environmental issues | severe water shortages, air pollution resulting in acid rain in both the US and Canada |

| Exclusive economic zone | 11,351,000 km2 (4,383,000 sq mi) |

Area

From 1989 through 1996, the total area of the US was listed as 9,372,610 km2 (3,618,780 sq mi) (land + inland water only). The listed total area changed to 9,629,091 km2 (3,717,813 sq mi) in 1997 (Great Lakes area and coastal waters added), to 9,631,418 km2 (3,718,711 sq mi) in 2004, to 9,631,420 km2 (3,718,710 sq mi) in 2006, and to 9,826,630 km2 (3,794,080 sq mi) in 2007 (territorial waters added). Currently, the CIA World Factbook gives 9,826,675 km2 (3,794,100 sq mi),[7] the United Nations Statistics Division gives 9,629,091 km2 (3,717,813 sq mi),[8] and the Encyclopedia Britannica gives 9,522,055 km2 (3,676,486 sq mi) (Great Lakes area included but not coastal waters).[9] These sources consider only the 50 states and the Federal District, and exclude overseas territories. The US has the 2nd largest Exclusive Economic Zone of 11,351,000 km2 (4,383,000 sq mi).

By total area (water as well as land), the United States is either slightly larger or smaller than the People's Republic of China, making it the world's third or fourth largest country. China and the United States are smaller than Russia and Canada in total area, but are larger than Brazil. By land area only (exclusive of waters), the United States is the world's third largest country, after Russia and China, with Canada in fourth. Whether the US or China is the third largest country by total area depends on two factors: (1) The validity of China's claim on Aksai Chin and Trans-Karakoram Tract (both these territories are also claimed by India, so are not counted); and (2) How the US calculates its own surface area. Since the initial publishing of the World Factbook, the CIA has updated the total area of United States a number of times.[10]

General characteristics

The United States shares land borders with Canada (to the north) and Mexico (to the south), and a territorial water border with Russia in the northwest, and two territorial water borders in the southeast between Florida and Cuba, and Florida and the Bahamas. The contiguous forty-eight states are otherwise bounded by the Pacific Ocean on the west, the Atlantic Ocean on the east, and the Gulf of Mexico to the southeast. Alaska borders the Pacific Ocean to the south and southwest, the Bering Strait to the west, and the Arctic Ocean to the north, while Hawaii lies far to the southwest of the mainland in the Pacific Ocean.

Forty-eight of the states are in the single region between Canada and Mexico; this group is referred to, with varying precision and formality, as the contiguous United States, and as the Lower 48. Alaska, which is included in the term continental United States, is located at the northwestern end of North America.

The capital city, Washington, District of Columbia, is a federal district located on land donated by the state of Maryland. (Virginia had also donated land, but it was returned in 1849.) The United States also has overseas territories (Insular areas) with varying levels of autonomy and organization: in the Caribbean the territories of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands (formerly the Danish Virgin Islands, purchased by the US at the beginning of WW2), and in the Pacific the inhabited territories of American Samoa, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, along with a number of uninhabited island territories. Some of the territories acquired were a part of United States imperialism, or to gain access to the east.

Nearly all of the United States is in the northern hemisphere—the exceptions are American Samoa and Jarvis Island.[11]

Physiographic divisions

The eastern United States has a varied topography. A broad, flat coastal plain lines the Atlantic and Gulf shores from the Texas-Mexico border to New York City, and includes the Florida peninsula. This broad coastal plain and barrier islands make up the widest and longest beaches in the United States, much of it composed of soft, white sands. The Florida Keys are a string of coral islands that reach the southernmost city on the United States mainland (Key West). Areas further inland feature rolling hills, mountains, and a diverse collection of temperate and subtropical moist and wet forests. Parts of interior Florida and South Carolina are also home to sandhill communities. The Appalachian Mountains form a line of low mountains separating the eastern seaboard from the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Basin. New England features rocky seacoasts and rugged mountains with peaks up to 6200 feet and valleys dotted with rivers and streams. Offshore Islands dot the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. A recent global remote sensing analysis suggested that there were 6,622 km² of tidal flats in the United States, making it the 4th ranked country in terms of tidal flat area.[12]

The five Great Lakes are located in the north-central portion of the country, four of them forming part of the border with Canada; only Lake Michigan is situated entirely within United States. The southeast United States, generally stretching from the Ohio River southwards, includes a variety of warm temperate and subtropical moist and wet forests, as well as warm temperate and subtropical dry forests nearer the Great Plains in the west of the region. West of the Appalachians lies the lush Mississippi River basin and two large eastern tributaries, the Ohio River and the Tennessee River. The Ohio and Tennessee Valleys and the Midwest consist largely of rolling hills, interior highlands and small mountains, jungly marsh and swampland near the Ohio River, and productive farmland, stretching south to the Gulf Coast. The Midwest also has a vast amount of cave systems.

The Great Plains lie west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains. A large portion of the country's agricultural products are grown in the Great Plains. Before their general conversion to farmland, the Great Plains were noted for their extensive grasslands, from tallgrass prairie in the eastern plains to shortgrass steppe in the western High Plains. Elevation rises gradually from less than a few hundred feet near the Mississippi River to more than a mile high in the High Plains. The generally low relief of the plains is broken in several places, most notably in the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains, which form the U.S. Interior Highlands, the only major mountainous region between the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachian Mountains.[13][14]

The Great Plains come to an abrupt end at the Rocky Mountains. The Rocky Mountains form a large portion of the Western U.S., entering from Canada and stretching nearly to Mexico. The Rocky Mountain region is the highest region of the United States by average elevation. The Rocky Mountains generally contain fairly mild slopes and wider peaks compared to some of the other great mountain ranges, with a few exceptions (such as the Teton Mountains in Wyoming and the Sawatch Range in Colorado). The highest peaks of the Rockies are found in Colorado, the tallest peak being Mount Elbert at 14,440 ft (4,400 m). In addition, instead of being one generally continuous and solid mountain range, it is broken up into a number of smaller, intermittent mountain ranges, forming a large series of basins and valleys.

West of the Rocky Mountains lies the Intermontane Plateaus (also known as the Intermountain West), a large, arid desert lying between the Rockies and the Cascades and Sierra Nevada ranges. The large southern portion, known as the Great Basin, consists of salt flats, drainage basins, and many small north–south mountain ranges. The Southwest is predominantly a low-lying desert region. A portion known as the Colorado Plateau, centered around the Four Corners region, is considered to have some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. It is accentuated in such national parks as Grand Canyon, Arches, Mesa Verde and Bryce Canyon, among others. Other smaller Intermontane areas include the Columbia Plateau covering eastern Washington, western Idaho and northeast Oregon and the Snake River Plain in Southern Idaho.

The Intermontane Plateaus come to an end at the Cascade Range and the Sierra Nevada. The Cascades consist of largely intermittent, volcanic mountains, many rising prominently from the surrounding landscape. The Sierra Nevada, further south, is a high, rugged, and dense mountain range. It contains the highest point in the contiguous 48 states, Mount Whitney (14,505 ft or 4,421 m). It is located at the boundary between California's Inyo and Tulare counties, just 84.6 mi or 136.2 km west-northwest of the lowest point in North America at the Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park at 279 ft or 85 m below sea level.[15]

These areas contain some spectacular scenery as well, as evidenced by such national parks as Yosemite and Mount Rainier. West of the Cascades and Sierra Nevada is a series of valleys, such as the Central Valley in California and the Willamette Valley in Oregon. Along the coast is a series of low mountain ranges known as the Pacific Coast Ranges.

Alaska contains some of the most dramatic scenery in the country. Tall, prominent mountain ranges rise up sharply from broad, flat tundra plains. On the islands off the south and southwest coast are many volcanoes. Hawaii, far to the south of Alaska in the Pacific Ocean, is a chain of tropical, volcanic islands, popular as a tourist destination for many from East Asia and the mainland United States.

The territories of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands encompass a number of tropical isles in the northeastern Caribbean Sea. In the Pacific Ocean the territories of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands occupy the limestone and volcanic isles of the Mariana archipelago, and American Samoa (the only populated US territory in the southern hemisphere) encompasses volcanic peaks and coral atolls in the eastern part of the Samoan Islands chain.[note 3]

Physiographic regions

The geography of the United States varies across its immense area. Within the continental U.S., eight distinct physiographic divisions exist, though each is composed of several smaller physiographic subdivisions.[16] These major divisions are:

- Laurentian Upland – part of the Canadian Shield that extends into the northern United States Great Lakes area.

- Atlantic Plain – the coastal regions of the eastern and southern parts includes the continental shelf, the Atlantic Coast and the Gulf Coast.

- Appalachian Highlands – lying on the eastern side of the United States, it includes the Appalachian Mountains, the Watchung Mountains, the Adirondacks and New England province originally containing the Great Eastern Forest, a stretch of mixed temperature and subtropical montane forests, some of which are rainforests.

- Interior Plains – part of the interior continental United States, it includes the Great Plains, as well as a number of highland and mountainous regions, like the Black Hills, dense cave systems, painted hills and badland features.

- Interior Highlands – also part of the interior continental United States, this division includes the Ozark Plateau, the Ouachita Mountains, and other smaller mountain systems. This region is located largely in the warm temperate/subtropical moist and dry forest biomes.

- Rocky Mountain System – one branch of the Cordilleran system lying far inland in the western states.

- Intermontane Plateaus – also divided into the Columbia Plateau, the Colorado Plateau and the Basin and Range Province, it is a system of plateaus, basins, ranges and gorges between the Rocky and Pacific Mountain Systems. It is the setting for the Grand Canyon, the Great Basin and Death Valley.

- Pacific Mountain System – the coastal mountain ranges and features in the west coast of the United States.

The Atlantic coast of the United States is low, with minor exceptions. The Appalachian Highland owes its oblique northeast–southwest trend to crustal deformations which in very early geological time gave a beginning to what later came to be the Appalachian mountain system. This system had its climax of deformation so long ago (probably in Permian time) that it has since then been very generally reduced to moderate or low relief. It owes its present-day altitude either to renewed elevations along the earlier lines or to the survival of the most resistant rocks as residual mountains. The oblique trend of this coast would be even more pronounced but for a comparatively modern crustal movement, causing a depression in the northeast resulting in an encroachment of the sea upon the land. Additionally, the southeastern section has undergone an elevation resulting in the advance of the land upon the sea.

While the Atlantic coast is relatively low, the Pacific coast is, with few exceptions, hilly or mountainous. This coast has been defined chiefly by geologically recent crustal deformations, and hence still preserves a greater relief than that of the Atlantic. The low Atlantic coast and the hilly or mountainous Pacific coast foreshadow the leading features in the distribution of mountains within the United States.

The east coast Appalachian system, originally forest covered, is relatively low and narrow and is bordered on the southeast and south by an important coastal plain. The Cordilleran system on the western side of the continent is lofty, broad and complicated having two branches, the Rocky Mountain System and the Pacific Mountain System. In between these mountain systems lie the Intermontane Plateaus. Both the Columbia River and Colorado River rise far inland near the easternmost members of the Cordilleran system, and flow through plateaus and intermontane basins to the ocean. Heavy forests cover the northwest coast, but elsewhere trees are found only on the higher ranges below the Alpine region. The intermontane valleys, plateaus and basins range from treeless to desert with the most arid region being in the southwest.

The Laurentian Highlands, the Interior Plains and the Interior Highlands lie between the two coasts, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico northward, far beyond the national boundary, to the Arctic Ocean. The central plains are divided by a hardly perceptible height of land into a Canadian and a United States portion. It is from the United States side, that the great Mississippi system discharges southward to the Gulf of Mexico. The upper Mississippi and some of the Ohio basin is the semi-arid prairie region, with trees originally only along the watercourses. The uplands towards the Appalachians were included in the great eastern forested area, while the western part of the plains has so dry a climate that its native plant life is scanty, and in the south it is practically barren.

Elevation extremes:

- Lowest point: Death Valley, Inyo County, California −280 ft (−85.3 m)

- Highest point: Denali, Denali Borough, Alaska 20,310 ft (6,190.5 m)

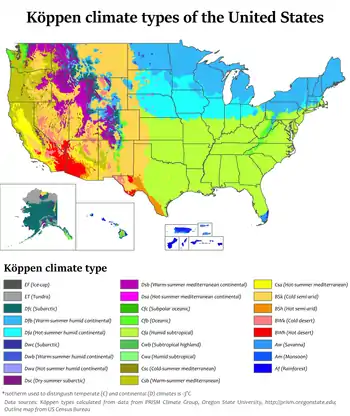

Climate

Due to its large size and wide range of geographic features, the United States contains examples of nearly every global climate. The climate is subtropical in the Southern United States, continental in the north, tropical in Hawaii and southern Florida, polar in Alaska, semiarid in the Great Plains west of the 100th meridian, Mediterranean in coastal California and arid in the Great Basin and the Southwest. Its comparatively favorable agricultural climate contributed (in part) to the country's rise as a world power, with infrequent severe drought in the major agricultural regions, a general lack of widespread flooding, and a mainly temperate climate that receives adequate precipitation.

The main influence on U.S. weather is the polar jet stream which migrates northward into Canada in the summer months, and then southward into the US in the winter months. The jet stream brings in large low pressure systems from the northern Pacific Ocean that enter the US mainland over the Pacific Northwest. The Cascade Range, Sierra Nevada, and Rocky Mountains pick up most of the moisture from these systems as they move eastward. Greatly diminished by the time they reach the High Plains, much of the moisture has been sapped by the orographic effect as it is forced over several mountain ranges.

Once it moves over the Great Plains, uninterrupted flat land allows it to reorganize and can lead to major clashes of air masses. In addition, moisture from the Gulf of Mexico is often drawn northward. When combined with a powerful jet stream, this can lead to violent thunderstorms, especially during spring and summer. Sometimes during winter these storms can combine with another low pressure system as they move up the East Coast and into the Atlantic Ocean, where they intensify rapidly. These storms are known as Nor'easters and often bring widespread, heavy rain, wind, and snowfall to New England. The uninterrupted grasslands of the Great Plains also lead to some of the most extreme climate swings in the world. Temperatures can rise or drop rapidly and winds can be extreme, and the flow of heat waves or Arctic air masses often advance uninterrupted through the plains.

The Great Basin and Columbia Plateau (the Intermontane Plateaus) are arid or semiarid regions that lie in the rain shadow of the Cascades and Sierra Nevada. Precipitation averages less than 15 inches (38 cm). The Southwest is a hot desert, with temperatures exceeding 100 °F (37.8 °C) for several weeks at a time in summer. The Southwest and the Great Basin are also affected by the monsoon from the Gulf of California from July to September, which brings localized but often severe thunderstorms to the region.

Much of California consists of a Mediterranean climate, with sometimes excessive rainfall from October–April and nearly no rain the rest of the year. In the Pacific Northwest rain falls year-round, but is much heavier during winter and spring. The mountains of the west receive abundant precipitation and very heavy snowfall. The Cascades are one of the snowiest places in the world, with some places averaging over 600 inches (1,524 cm) of snow annually, but the lower elevations closer to the coast receive very little snow.

Florida has a subtropical climate in the northern part of the state and a tropical climate in the southern part of the state. Summers are wet and winters are dry in Florida. Annually much of Florida, as well as the deep southern states, are frost-free. The mild winters of Florida allow a massive tropical fruit industry to thrive in the central part of the state, making the US second to only Brazil in citrus production in the world.

Another significant (but localized) weather effect is lake-effect snow that falls south and east of the Great Lakes, especially in the hilly portions of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and on the Tug Hill Plateau in New York. The lake effect dumped well over 5 feet (1.52 m) of snow in the area of Buffalo, New York throughout the 2006–2007 winter. The Wasatch Front and Wasatch Range in Utah can also receive significant lake effect accumulations from the Great Salt Lake.

Extremes

In northern Alaska, tundra and arctic conditions predominate, where the temperature has fallen as low as −80 °F (−62.2 °C).[17] On the other end of the spectrum, Death Valley, California once reached 134 °F (56.7 °C), the highest temperature ever recorded on Earth.[18][19]

On average, the mountains of the western states receive the highest levels of snowfall on Earth. The greatest annual snowfall level is at Mount Rainier in Washington, at 692 inches (1,758 cm); the record there was 1,122 inches (2,850 cm) in the winter of 1971–72. This record was broken by the Mt. Baker Ski Area in northwestern Washington which reported 1,140 inches (2,896 cm) of snowfall for the 1998–99 snowfall season. Other places with significant snowfall outside the Cascade Range are the Wasatch Mountains in Utah, the San Juan Mountains in Colorado, and the Sierra Nevada in California.

In the east, the region near the Great Lakes and the mountains of the Northeast receive the most snowfall, although such snowfall levels do not near snowfall levels in the western United States. Along the northwestern Pacific coast, rainfall is greater than anywhere else in the continental U.S., with Quinault Rainforest in Washington having an average of 137 inches (348 cm).[21] Hawaii receives even more, with 404 inches (1,026 cm) measured annually in the Big Bog, in Maui.[22] Pago Pago Harbor in American Samoa is the rainiest harbor in the world (because of the 523 meter Rainmaker Mountain).[20] The Mojave Desert, in the southwest, is home to the driest locale in the U.S. Yuma, Arizona, has an average of 2.63 inches (6.7 cm) of precipitation each year.[23]

In central portions of the U.S., tornadoes are more common than anywhere else on Earth[24] and touch down most commonly in the spring and summer. Deadly and destructive hurricanes occur almost every year along the Atlantic seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico. The Appalachian region and the Midwest experience the worst floods, though virtually no area in the U.S. is immune to flooding. The Southwest has the worst droughts; one is thought to have lasted over 500 years and to have hurt Ancestral Pueblo peoples.[25] The West is affected by large wildfires each year.

Natural disasters

The United States is affected by a variety of natural disasters yearly. Although drought is rare, it has occasionally caused major disruption, such as during the Dust Bowl (1931–1942). Farmland failed throughout the Plains, entire regions were substantially depopulated, and dust storms ravaged the land.

Tornadoes and hurricanes

The Great Plains and Midwest, due to the contrasting air masses, see frequent severe thunderstorms and tornado outbreaks during spring and summer with around 1,000 tornadoes occurring each year.[26] The strip of land from north Texas north to Kansas and Nebraska and east into Tennessee is known as Tornado Alley, where many houses have tornado shelters and many towns have tornado sirens due to the very frequent tornado formations in the region.

Hurricanes are another natural disaster found in the US, which can hit anywhere along the Gulf Coast or the Atlantic Coast as well as Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean. Particularly at risk are the central and southern Texas coasts, the area from southeastern Louisiana east to the Florida Panhandle, peninsular Florida, and the Outer Banks of North Carolina, although any portion of the coast could be struck. The U.S. territories and possessions in the Caribbean, such as Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, are also vulnerable to hurricanes due to their location in the Caribbean Sea.

Hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30, with a peak from mid-August through early October. Some of the more devastating hurricanes have included the Galveston Hurricane of 1900, Hurricane Andrew in 1992, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and Hurricane Harvey and Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Hurricanes (known as cyclones in the Pacific Ocean) fail to landfall on the Pacific Coast of the United States due to water temperatures being too cool to sustain them. However, the remnants of tropical cyclones from the Eastern Pacific occasionally impact the western United States, bringing moderate to heavy rainfall.

Flooding

Occasional severe flooding is experienced. There was the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the Great Flood of 1993, and widespread flooding and mudslides caused by the 1982–83 El Niño event in the western United States. Flooding is still prevalent, mostly on the Eastern Coast, during hurricanes or other inclement weather, for example in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy devastated the region. Localized flooding can, however, occur anywhere, and mudslides from heavy rain can cause problems in any mountainous area, particularly the Southwest. Large stretches of desert shrub in the west can fuel the spread of wildfires. The narrow canyons of many mountain areas in the west and severe thunderstorm activity during the summer lead to sometimes devastating flash floods as well, while nor'easter snowstorms can bring activity to a halt throughout the Northeast (although heavy snowstorms can occur almost anywhere).

Geologic

The West Coast of the continental United States makes up part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, an area of heavy tectonic and volcanic activity that is the source of 90% of the world's earthquakes. The American Northwest sees the highest concentration of active volcanoes in the United States, in Washington, Oregon and northern California along the Cascade Mountains. There are several active volcanoes located in the islands of Hawaii, including Kilauea in ongoing eruption since 1983, but they do not typically adversely affect the inhabitants of the islands. There has not been a major life-threatening eruption on the Hawaiian islands since the 17th century. Volcanic eruptions can occasionally be devastating, such as in the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington.

The Ring of Fire makes California and southern Alaska particularly vulnerable to earthquakes. Earthquakes can cause extensive damage, such as the 1906 San Francisco earthquake or the 1964 Good Friday earthquake near Anchorage, Alaska. California is well known for seismic activity, and requires large structures to be earthquake resistant to minimize loss of life and property.[27] Outside of devastating earthquakes, California experiences minor earthquakes on a regular basis.

There have been about 100 significant earthquakes annually from 2010 to 2012. Past averages were 21 a year. This is believed to be due to the deep disposal of wastewater from fracking. None has exceeded a magnitude of 5.6, and no one has been killed.[28]

Other natural disasters

Other natural disasters include: tsunamis around Pacific Basin, mud slides in California, and forest fires in the western half of the contiguous U.S. Although drought is relatively rare, it has occasionally caused major economic and social disruption, such as during the Dust Bowl (1931–1942), which resulted in widespread crop failures and dust storms, beginning in the southern Great Plains and reaching to the Atlantic Ocean.

Public lands

The United States holds many areas for the use and enjoyment of the public. These include national parks, national monuments, national forests, wilderness areas, and other areas. For lists of areas, see the following articles:

- List of National Parks of the United States

- List of National Natural Landmarks

- List of U.S. National Forests

- List of U.S. Wilderness Areas

Human

In terms of human geography, the United States is inhabited by a diverse set of ethnicities and cultures.

See also

![]() United States portal

United States portal

- County (United States)

- Geographic centers of the United States

- Geography of Puerto Rico

- Geography's impact on colonial America

- Index of United States-related articles

- List of extreme points of the United States

- List of fjords of the United States

- List of islands of the United States

- Lists of landforms of the United States

- List of North American deserts

- List of snowiest places in the United States by state

- Protected areas of the United States

- Public Land Survey System

- Territorial evolution of the United States

Regions

- Historic regions of the United States

- List of regions of the United States

Mountains

- List of mountain peaks of the United States

- List of mountains of the United States

Notes

- Areas not on the map: Aleutian Islands (Alaska); Northwest Hawaiian Islands (Hawaii); Mona Island (Puerto Rico); Rota and Northern Islands Municipality (Northern Mariana Islands); Manu'a Islands, Rose Atoll and Swains Island (American Samoa) and the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands

- The United States has a maritime border with the United Kingdom because the U.S. Virgin Islands borders the British Virgin Islands.[2] Puerto Rico has a maritime border with the Dominican Republic.[3] American Samoa has a maritime border with the Cook Islands (see Cook Islands–United States Maritime Boundary Treaty).[4][5] American Samoa also has maritime borders with independent Samoa and Niue.[6]

- One island in American Samoa (Swains Island) is not in the Samoan Islands — it is in the Tokelau island chain.

References

- U.S. State Department, Common Core Document to U.N. Committee on Human Rights, December 30, 2011, Item 22, 27, 80; Homeland Security Public Law 107-296 Sec.2.(16)(A); Presidential Proclamation of national jurisdiction

- https://www.britannica.com/place/United-States-Virgin-Islands. Britannica.com. United States Virgin Islands. Retrieved July 3, 2020. Archived April 29, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Puerto-RicoBritannica.com. Puerto Rico. Retrieved July 3, 2020. Archived July 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Anderson, Ewan W. (2003). International Boundaries: A Geopolitical Atlas. Routledge: New York. ISBN 9781579583750; OCLC 54061586

- Charney, Jonathan I., David A. Colson, Robert W. Smith. (2005). International Maritime Boundaries, 5 vols. Hotei Publishing: Leiden.

- http://www.pacgeo.org/static/maritimeboundaries/Pacgeo.org. Maritime Boundaries. Retrieved July 3, 2020. Archived July 31, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- "United States". The World Factbook. CIA. September 30, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- "Population by Sex, Rate of Population Increase, Surface Area and Density" (PDF). Demographic Yearbook 2005. UN Statistics Division. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- "United States". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- Countries of the World: 21 Years of World Facts, geographic.org, retrieved August 17, 2008

- https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/graphics/ref_maps/physical/pdf/standard_time_zones_of_the_world.pdf Archived January 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine CIA World Factbook – Standard Time Zones of the World, May 2018. (Map of the world showing the location of the contiguous U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, and the U.S. territories. Territories south of the "0" horizontal line (the equator) are in the southern hemisphere). Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Murray, N.J.; Phinn, S.R.; DeWitt, M.; Ferrari, R.; Johnston, R.; Lyons, M.B.; Clinton, N.; Thau, D.; Fuller, R.A. (2019). "The global distribution and trajectory of tidal flats". Nature. 565 (7738): 222–225. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0805-8. PMID 30568300. S2CID 56481043.

- "Managing Upland Forests of the Midsouth". United States Forestry Service. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- "A Tapestry of Time and Terrain: The Union of Two Maps – Geology and Topography". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- "USGS National Elevation Dataset (NED) 1 meter Downloadable Data Collection from The National Map 3D Elevation Program (3DEP) – National Geospatial Data Asset (NGDA) National Elevation Data Set (NED)". United States Geological Survey. September 21, 2015. Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- "Physiographic Regions". United States Geological Survey. April 17, 2003. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- Williams, Jack Each state's low temperature record, USA today, URL accessed 13 June 2006.

- "Weather and Climate" (PDF). Official website for Death Valley National Park. National Park Service U. S. Department of the Interior. January 2002. pp. 1–2. Retrieved October 5, 2006.

- "WMO Press release No. 956". World Meteorological Organization. September 13, 2012. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- Lonely Planet. "Rainmaker Mountain in Tutuila". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- National Atlas, Average Annual Precipitation, 1961–1990 Archived 2006-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, URL accessed 15 June 2006.

- Longman, Ryan J.; Giambelluca, Thomas W.; Nullet, Michael A.; Loope, Lloyd L. (July 2015). "ScholarSpace at University of Hawaii at Manoa: Climatology of Haleakalā". hdl:10125/36675. R.J. Longman and T.W. Giambelluca. Climatology of Haleakala. Climatology of Haleakalā Technical Report No. 193. Volume 1, Issue 1. Pages 105–106. 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Hereford, Richard, et al., Precipitation History of the Mojave Desert Region, 1893–2001, U.S. Geological Survey, Fact Sheet 117-03, URL accessed 13 June 2006.

- NOVA, Tornado Heaven, Hunt for the Supertwister, URL accessed 15 June 2006.

- O'Connor, Jim E. and John E. Costa, Large Floods in the United States: Where Thley Happen and Why, U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1245, URL accessed 13 June 2006.

- NSSL: Severe Weather 101 Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine. Nssl.noaa.gov. Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- "Building Safer Structures". Archived from the original on May 11, 2010.

- Vergano, Dan (July 12, 2013). "Study:Earthquake increase tied to energy boom". The Burlington Free Press. Burlington, Vermont. pp. 10A. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

Further reading

- Brown, Ralph Hall, Historical Geography of the United States, New York : Harcourt, Brace, 1948

- Stein, Mark, How the States Got Their Shapes, New York : Smithsonian Books/Collins, 2008. ISBN 978-0-06-143138-8

External links

- USGS: Tapestry of Time and Terrain

- United States Geological Survey – Maintains free aerial maps

- National Atlas of the United States of America

- US Map