Gray fox

The gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), or grey fox, is an omnivorous mammal of the family Canidae, widespread throughout North America and Central America. This species and its only congener, the diminutive island fox (Urocyon littoralis) of the California Channel Islands, are the only living members of the genus Urocyon, which is considered to be genetically basal to all other living canids. Its species name cinereoargenteus means "ashen silver".

| Gray fox | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Urocyon |

| Species: | U. cinereoargenteus |

| Binomial name | |

| Urocyon cinereoargenteus (Schreber, 1775) | |

| |

| Gray fox range | |

It was once the most common fox in the eastern United States, and though still found there, human advancement and deforestation allowed the red fox to become the predominant fox-like canid. Despite this post-colonial competition, the gray fox has been able to thrive in urban and suburban environments, one of the best examples being southern Florida.[2][3] The Pacific States and Great Lakes region still have the gray fox as their prevalent fox.[4][5][6]

Etymology

The genus Urocyon comes from the Latin 'uro' meaning tail, and 'cyon', meaning dog. The species epithet cinereoargenteus is a combination of 'cinereo' meaning ashen, and 'argenteus' (from argentum), meaning 'silver', referencing the color of the tail.

Description

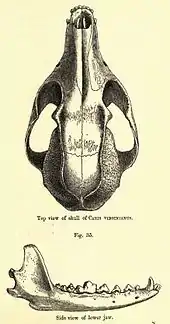

The gray fox is mainly distinguished from most other canids by its grizzled upper parts, black stripe down its tail and strong neck, ending in a black-tipped tail, while the skull can be easily distinguished from all other North American canids by its widely separated temporal ridges that form a ‘U’-shape. Like other canids, the fox's ears and muzzle are angular and pointed. Its claws tend to be lengthier and curved.

There is little sexual dimorphism, save for the females being slightly smaller than males. The gray fox ranges from 76 to 112.5 cm (29.9 to 44.3 in) in total length. The tail measures 27.5 to 44.3 cm (10.8 to 17.4 in) of that length and its hind feet measure 100 to 150 mm (3.9 to 5.9 in). The gray fox typically weighs 3.6 to 7 kg (7.9 to 15.4 lb), though exceptionally can weigh as much as 9 kg (20 lb).[7][8][9][10] The grey fox is readily distinguished from the red fox by its obvious lack of the "black stockings" that stand out on the red fox. The grey fox has a stripe of black hair that runs along the middle of its tail, and individual guard hairs that are banded with white, gray, and black.[11] The gray fox displays white on the ears, throat, chest, belly, and hind legs.[11] Gray foxes also have black around their eyes, on the lips, and on their noses.[12]

In contrast to all Vulpes and related (Arctic and fennec) foxes, the gray fox has oval (instead of slit-like) pupils.[13](p122) The gray fox also has reddish coloration on parts of its body, including the legs, sides, feet, chest, and back and sides of the head and neck.[10] The stripe on the fox's tail ends in a black tip as well.[14] Their weight can be similar to that of a red fox, but gray foxes appear smaller because their fur isn't as long and they have shorter limbs.[15]

The dental formula of the U. cinereoargenteus is 3.1.4.23.1.4.3 = 42.[11]

Origin and genetics

The gray fox appeared in North America during the mid-Pliocene (Hemphillian land animal age) epoch 3.6 million years ago (AEO) with the first fossil evidence found at the lower 111 Ranch site, Graham County, Arizona with contemporary mammals like the giant sloth, the elephant-like Cuvieronius, the large-headed llama, and the early small horses of Nannippus and Equus.[16] Faunal remains at two northern California cave sites confirm the presence of the gray fox during the late Pleistocene.[17] Genetic analysis has shown that the gray fox migrated into the northeastern United States post-Pleistocene in association with the Medieval Climate Anomaly warming trend.[18]

Genetic analyses of the fox-like canids confirmed that the gray fox is a distinct genus from the red foxes (Vulpes spp.). The genus Urocyon is considered to be the most basal of the living canids.[19] Genetically, the gray fox often clusters with two other ancient lineages: The east Asian raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) and the African bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis).[20]

The chromosome number is 66 (diploid) with a fundamental number of 70. The autosomes include 31 pairs of sub-graded subacrocentrics, but one only pair of metacentrics.[21]

Recent mitochondrial genetic studies suggests divergence of North American eastern and western gray foxes in the Irvingtonian mid-Pleistocene into separate sister taxa.[22] The gray fox's dwarf relative, the island fox, is likely descended from mainland gray foxes.[23] These foxes apparently were transported by humans to the islands and from island to island, and are descended from a minimum of 3–4 matrilineal founders.[22]

Distribution and habitat

The species occurs throughout most rocky, wooded, brushy regions of the southern half of North America from southern Canada (Manitoba through southeastern Quebec)[24] to the northern part of South America (Venezuela and Colombia), excluding the mountains of northwestern United States.[25] It is the only canid whose natural range spans both North and South America.[26] In some areas, high population densities exist near brush-covered bluffs.[11]

Behavior

The gray fox is specifically adapted to climb trees. Its strong, hooked claws allow it to scramble up trees to escape many predators, such as the domestic dog or the coyote,[27] or to reach tree-bound or arboreal food sources. It can climb branchless, vertical trunks to heights of 18 meters and jump from branch to branch.[28] It descends primarily by jumping from branch to branch, or by descending slowly backwards like a domestic cat. The gray fox is primarily nocturnal or crepuscular and makes its den in hollow trees, stumps or appropriated burrows during the day. Such gray fox tree dens may be located 30 ft above the ground.[13](p122) For the most part, they rest on the ground rather than higher up in trees.

Prior to European colonization of North America, the red fox was found primarily in boreal forest and the gray fox in deciduous forest. With the increase in human populations in North America, their habitat selection has adapted: Gray foxes that live near human populations tend to choose areas near hardwood trees, locations used primarily by humans, or roads to utilize as their habitat.

The increase of coyote populations around North America has reduced certain fox populations, so gray foxes have to choose a habitat that will allow them to escape the coyote threat as much as possible, hence the choice of habitat nearer to areas where humans are active. The larger predators of the gray fox, like coyotes and bobcats, tend to avoid human-use areas and paved roads, making this habitat useful for the gray fox. They heavily utilize the edges of forests as a travel corridor, which is used for primary movement from place to place. Their choices do not change based on sex, the season, or the time of day. They also do the majority of their hunting in edges, and use them to escape from predators as well. Gray foxes are thus known as an “edge species”.[29]

Interspecies competition

Gray foxes often hunt for the same prey as bobcats and coyotes who occupy the same region. To avoid interspecific competition, the gray fox has developed certain behaviors and habits to increase their survival chances. In regions where gray foxes and coyotes hunt for the same food, the gray fox has been observed to give space to the coyote, staying within its own established range for hunting.[30][31] Gray foxes might also avoid their competitors by occupying different habitats than them. In California, gray foxes do this by living in chaparral where their competitors are fewer and the low shrubbery provides them a greater chance to escape from a dangerous encounter.[31] It also has been suggested that gray foxes could be more active at night than during the day to avoid their larger, diurnal competitors.[31]

Still, gray foxes frequently fall victim to bobcats and coyotes. When killed, the carcasses are often unconsumed, suggesting they are victims of intraguild predation.[30] These gray foxes are often killed on or near the boundary of their established range, when they begin to interfere with their competitors.[30] Gray foxes are known as mesopredators because they are mid-tier predators and their prey consists mostly of smaller mammals, while coyotes are known as de facto apex predators due to the removal of other apex predators like wolves in North America.[32][33] This explains the gray fox's tendency to change behavior in response to the coyote threat, as they are essentially lower on the food chain.

Reproduction

The gray fox is assumed to be monogamous, like other foxes. The breeding season of the gray fox varies geographically; in Michigan, the gray fox mates in early March, in Alabama, breeding peaks occur in February. The gestation period lasts approximately 53 days. Litter size ranges from 1–7, with a mean of 3.8 young per female.

The sexual maturity of females is around 10 months of age. Kits begin to hunt with their parents at the age of 3 months. By the time that they are 4 months old, the kits will have developed their permanent dentition and can now easily forage on their own. The family group remains together until the autumn, when the young males reach sexual maturity, then they disperse.[21] In a study of 9 juvenile gray foxes, only the males dispersed up to 84 km (52 mi). The juvenile females stayed within proximity of the den within 3 km (1.9 mi) and always returned.[34] On the other hand, adult gray foxes showed no signs of dispersion for either gender.[35] The gray fox will typically live between six to ten years.[36]

The annual reproductive cycle of males has been described through epididymal smears and become fertile earlier and remain fertile longer than the fertility of females.[21]

Logs, trees, rocks, burrows, or abandoned dwellings serve as suitable den sites. Dens are used at any time during the year but mostly during whelping season. Dens are built in brushy or wooded regions and are better concealed than the dens of the red fox.[11]

Diet

The gray fox is an omnivorous, solitary hunter. It frequently preys on the eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) in the eastern U.S., though it will readily catch voles, shrews, and birds. In California, the gray fox primarily eats rodents, followed by lagomorphs, e.g. jackrabbit, brush rabbit, etc.[27] In some parts of the Western United States (such as in the Zion National Park in Utah), the gray fox is primarily insectivorous and herbivorous.[13](p124) Fruit is an important component of the diet of the gray fox and they seek whatever fruits are readily available, generally eating more vegetable matter than does the red fox (Vulpes vulpes).[7] Generally, there is an increase in fruits and invertebrates within the gray fox's diet in the transition from winter to spring. As nuts, grains, and fruits become more numerous, they are cached by foxes. Typically, they attempt to cover the area with their scent either through their scent glands or urine. This marking serves the dual purpose of allowing them to find the food again later and preventing other animals from taking it.[37]

Ecosystem role

Since woodrats, cotton rats, and mice make up a large part of the gray fox's diet, they serve as important regulators of small rodent populations.

In addition to their beneficial predation on rodents, gray foxes are also less welcome hosts to some external and internal parasites, which include fleas, lice, nematodes, and tapeworms.[37] In the United States, the most common parasite of the gray fox is a flea (Pulex simulans); however, several new parasitic arthropods were found in populations in central Mexico, and a warming climate may encourage them to migrate north.[38]

Hunting

Gray foxes are hunted in the U.S. The intensity of the hunting has correlated with the value of their pelts. Between the 1970–1971 and 1975–1976 hunting seasons, the price of gray fox pelts greatly increased and the number of individuals hunted jumped over six-fold from 26,109 to 163,458.[21]

Subspecies

There are 16 subspecies recognized for the gray fox.[21]

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus borealis (New England)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus californicus (southern California)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus cinereoargenteus (eastern United States)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus costaricensis (Costa Rica)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus floridanus (Gulf states)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus fraterculus (Yucatán)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus furvus (Panama)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus guatemalae (southernmost Mexico south to Nicaragua)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus madrensis (southern Sonora, south-west Chihuahua, and north-west Durango)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus nigrirostris (south-west Mexico)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus ocythous (Central Plains states)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus orinomus (southern Mexico, Isthmus of Tehuantepec)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus peninsularis (Baja California)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus scottii (south-western United States and northern Mexico)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus townsendi (northern California and Oregon)

- Urocyon cinereoargenteus venezuelae (Colombia and Venezuela)

Parasites

Parasites of gray fox include trematode Metorchis conjunctus.[39]

See also

- Cozumel fox, a recently/nearly extinct grey fox formerly found on Mexico's Cozumel Island

- South American gray fox, also known as the gray zorro, but only distantly related

- Urocyon progressus, the extinct ancestor of the gray fox

References

- Roemer, G.; Cypher, B.; List, R. (2016). "Urocyon cinereoargenteus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22780A46178068. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T22780A46178068.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Fleshler, David (25 November 2015). "Gray foxes thrive in South Florida – but are rarely seen". Sun-Sentinel. South Florida. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- "Wild foxes dwell among us". Sun-Sentinel. South Florida. 23 September 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- Merrill, Andrea (25 February 2021). "Foxes of the Pacific Northwest". Animals of the Pacific Northwest. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- "Gray Fox". Irvine Ranch Conservancy. Wildlife spotlight. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- "Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus)". mnmammals.d.umn.edu. Minnesota mammals. Duluth, MN: University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- "Urocyon cinereoargenteus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- Boitani, Luigi (1984). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Mammals. Simon & Schuster / Touchstone Books. ISBN 978-0-671-42805-1.

- "Common gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus)". nsrl.ttu.edu. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- "Gray fox - Urocyon cinereoargenteus". Nature Works. nhpbs.org. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Fritzell, Haroldson, Erik, Kurt (November 1982). "Urocyon cinereoargenteus". Mammalian Species (189): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3503957. JSTOR 3503957.

- Castelló, José R. (11 September 2018). Canids of the World: Wolves, wild dogs, foxes, jackals, coyotes, and their relatives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 264–310. ISBN 978-0-691-18541-5.

- Alderton, David (1998). Foxes, Wolves, Lions, and Wild Dogs of the World. London, UK: Blandford. pp. 122, 124. ISBN 081605715X.

- "Gray fox". Wildlife Science Center. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- "Gray fox". www.ncwildlife.org. Learning mammal species. National Center for Wildlife. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- Alroy, John, Dr. (18 February 1993). "Collection 19656". Paleobiology database. Graham County, Arizona.

- Graham, R.W.; Lundelius, E.L., Jr. (2010). New data for North America with a temporal extension for the Blancan, Irvingtonian and early Rancholabrean (Report). FAUNMAP II Database (1.0 ed.). Retrieved 13 December 2015.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bozarth, Christine A.; Lance, Stacey L.; Civitello, David J.; Glenn, Julie L.; Maldonado, Jesus E. (2011). "Phylogeography of the gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) in the eastern United States" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 92 (2): 283–294. doi:10.1644/10-MAMM-A-141.1. S2CID 22567929. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Wayne, R.K.; Geffen, E.; Girman, D.J.; Koepfli, K.P.; Lau, L.M.; Marshall, C.R. (1997). "Molecular Systematics of the Canidae". Systematic Biology. 46 (4): 622–653. doi:10.1093/sysbio/46.4.622. PMID 11975336.

- Geffen, E.; Mercure, A.; Girman, D.J.; MacDonald, D.W.; Wayne, R.K. (September 1992). "Phylogenetic relationships of the fox-like canids: Mitochondrial DNA restriction fragment, site and cytochrome b sequence analyses". Journal of Zoology. London, UK. 228: 27–39. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb04430.x.

- Fritzell, Erik K.; Haroldson, Kurt J. (1982). "Urocyon cinereoargenteus" (PDF). Mammalian Species (189): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3503957. JSTOR 3503957. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Goddard, Natalie S.; Statham, Mark J.; Sacks, Benjamin N. (19 August 2015). "Mitochondrial analysis of the most basal canid reveals deep divergence between eastern and western North American gray foxes (Urocyon spp.) and ancient roots in Pleistocene California". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0136329. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1036329G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136329. PMC 4546004. PMID 26288066.

- Fuller, T.K.; Cypher, B.L. (2004). "Gray fox Urocyon cinereoargenteus". In Sillero-Zubiri, C.; Hoffman, M.; Macdonald, D.W. (eds.). Canids: Foxes, wolves, jackals, and dogs. Status survey and conservation action plan (PDF) (Report). Cambridge, UK: IUCN Publications. pp. 92–97. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Gray fox". Naturecanada.ca. Know our species. Nature Canada. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 582. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Kurten, B.; Anderson, E. (1980). Pleistocene Mammals of North America. New York, NY: Columbia University. ISBN 978-0231037334.

- Fedriani, J.M.; Fuller, T.K.; Sauvajot, R.M.; York, E.C. (2000). "Competition and intraguild predation among three sympatric carnivores". Oecologia. 125 (2): 258–270. Bibcode:2000Oecol.125..258F. doi:10.1007/s004420000448. hdl:10261/54628. PMID 24595837. S2CID 24289407.

- Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio; Hoffman, Michael; MacDonald, David W. (2004). Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals, and Dogs: Status survey and conservation action plan (Report). Gland, Switzerland / Cambridge, UK: IUCN. p. 95.

- Deuel, Nicholas R.; Conner, L. Mike; Miller, Karl V.; Chamberlain, Michael J.; Cherry, Michael J.; Tannenbaum, Larry V. (17 October 2017). "Habitat selection and diurnal refugia of gray foxes in southwestern Georgia, USA". PLOS ONE. 12 (10): e0186402. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1286402D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186402. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5645120. PMID 29040319.

- Farias, Veronica; Fuller, Todd K.; Wayne, Robert K.; Sauvajot, Raymond M. (16 June 2005). "Survival and cause-specific mortality of gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) in southern California". Journal of Zoology. 266 (3): 249–254. doi:10.1017/s0952836905006850. ISSN 0952-8369.

- Farías, Verónica (2 June 2012). "Activity and distribution of gray foxes (Urocyon Cinereoargenteus) in southern California". The Southwestern Naturalist. 57 (2): 176–181. doi:10.1894/0038-4909-57.2.176. S2CID 39115546. ProQuest 1034899017 – via Proquest.

- Wooster, Eamonn; Wallach, Arian D.; Ramp, Daniel (November 2019). "The wily and courageous red fox: Behavioural analysis of a mesopredator at resource points shared by an apex predator". Animals. 9 (11): 907. doi:10.3390/ani9110907. PMC 6912404. PMID 31683979.

- Jones, Brandon M.; Cove, Michael V.; Lashley, Marcus A.; Jackson, Victoria L. (February 2016). "Do coyotes Canis latrans influence occupancy of prey in suburban forest fragments?". Current Zoology. 62 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1093/cz/zov004. ISSN 1674-5507. PMC 5804128. PMID 29491884.

- Sheldon (1953)

- Follmann (1973)

- "Grey fox". Foxes worlds.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Vu, Long. "Urocyon cinereoargenteus (gray fox)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Hernández-Camacho, Norma; Pineda-López, Raúl Francisco; de Jesús Guerrero-Carrillo, María; Cantó-Alarcón, Germinal Jorge; Jones, Robert Wallace; Moreno-Pérez, Marco Antonio; et al. (1 August 2016). "Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) parasite diversity in central Mexico". International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife. 5 (2): 207–210. doi:10.1016/j.ijppaw.2016.06.003. ISSN 2213-2244. PMC 4930337. PMID 27408801.

- Mills, J.H.; Hirth, R.S. (1968). "Lesions caused by the hepatic trematode, Metorchis conjunctus, Cobbold, 1860: A comparative study in carnivora". Journal of Small Animal Practice. 9 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1968.tb04678.x. PMID 5688935.

External links

- "Skull morphology U. cinereoargenteus". digimorph.org.

- Gray fox filmed in Colorado (video).

- Gray fox filmed in Austin, Texas (video).