Hail to the Thief

Hail to the Thief is the sixth album by the English rock band Radiohead. It was released on 9 June 2003 through Parlophone internationally and a day later through Capitol Records in the United States. It was the last album released under Radiohead's record contract with EMI, the parent company of Parlophone and Capitol.

| Hail to the Thief | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 9 June 2003 | |||

| Recorded | September 2002 – February 2003 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 56:35 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer |

| |||

| Radiohead chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Hail to the Thief | ||||

| ||||

After transitioning to a more electronic style on their albums Kid A (2000) and Amnesiac (2001), which were recorded through protracted studio experimentation, Radiohead sought to work more spontaneously, combining electronic and rock music. They recorded most of Hail to the Thief in two weeks in Los Angeles with their longtime producer Nigel Godrich, focusing on live takes rather than overdubs.

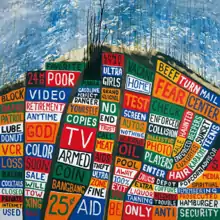

Songwriter Thom Yorke wrote lyrics influenced by the unfolding war on terror and the surrounding political discourse, incorporating influences from fairy tales and children's literature. The cover artwork, created by the artist Stanley Donwood, is a roadmap of Hollywood with words taken from roadside advertising in Los Angeles and from Yorke's lyrics.

Following a high-profile internet leak of unfinished material ten weeks before release, Hail to the Thief debuted at number one on the UK Albums Chart and number three on the US Billboard 200 chart. It was certified platinum in the UK and Canada and gold in several countries. It was promoted with singles and music videos for "There There", "Go to Sleep" and "2 + 2 = 5". Hail to the Thief received positive reviews; it was the fifth consecutive Radiohead album nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album, and won for the Grammy Award for Best Engineered Non-Classical Album.

Background

With their previous albums Kid A (2000) and Amnesiac (2001), recorded simultaneously, Radiohead replaced their guitar-led rock sound with a more electronic style.[1] For the tours, they learned how to perform the music live, combining synthetic sounds with rock instrumentation.[2] The singer, Thom Yorke, said: "Even with electronics, there is an element of spontaneous performance in using them. It was the tension between what's human and what's coming from the machines. That was stuff we were getting into."[2] Radiohead did not want to make a "big creative leap or statement" with their next album.[2]

In early 2002, after the Amnesiac tour had finished, Yorke sent his bandmates CDs of demos.[3] The three CDs, The Gloaming, Episcoval and Hold Your Prize, comprised electronic music alongside piano and guitar sketches.[4] Radiohead had tried to record some of the songs, such as "I Will", for Kid A and Amnesiac, but were not satisfied with the results.[3] They spent May and June 2002 arranging and rehearsing the songs before performing them on their tour of Spain and Portugal in July and August.[3]

Recording

In September 2002, Radiohead moved to Ocean Way Recording in Hollywood, Los Angeles, with their longtime producer Nigel Godrich.[5] The studio was suggested by Godrich, who had used it to produce records by Travis and Beck and thought it would be a "good change of scenery" for Radiohead.[6] Yorke said: "We were like, 'Do we want to fly halfway around the world to do this?' But it was terrific, because we worked really hard. We did a track a day. It was sort of like holiday camp."[2]

Kid A and Amnesiac were created through a years-long process of recording and editing that the drummer, Philip Selway, described as "manufacturing music in the studio".[7] For their next album, Radiohead sought to capture a more immediate, "live" sound.[3][8] Yorke said they wanted to spend less time "looking at computers and grids", and instead integrated computers into their performances with other instruments. He said "everything was about performance, like staging a play".[9]

Radiohead tried to work quickly and spontaneously, avoiding procrastination and overanalysis.[3] The guitarist Jonny Greenwood said: "We didn't really have time to be stressed about what we did. We got to the end of the second week before we even heard what we did on the first two days, and didn't even remember recording it or who was playing things. Which is a magical way of doing things."[10] Yorke was forced to write lyrics differently, as he did not have time to rewrite them in the studio.[11] For some songs, he returned to the method of cutting up words and arranging them randomly he had employed for Kid A and Amnesiac.[12]

Most electronic elements were not overdubbed, but recorded live in the studio.[13] Greenwood used the music programming language Max to sample and manipulate the band's playing;[13] for example, he used it to process his guitar on "Go To Sleep", creating a random stuttering effect.[14] He continued to use modular synthesisers and the ondes Martenot, an early electronic instrument similar to a theremin.[15][16][17] After having used effects pedals heavily on previous albums, he challenged himself to create interesting guitar parts without effects.[18]

Inspired by the Beatles, Radiohead tried to keep the songs concise.[19] The opening track, "2 + 2 = 5", was recorded as a studio test and finished in two hours.[3] Radiohead struggled to record "There There"; after rerecording it in their Oxfordshire studio, Yorke was so relieved to have captured it he wept, feeling it was the band's best work.[3] Radiohead had recorded an electronic version of "I Will" in the Kid A and Amnesiac sessions, but abandoned it as "dodgy Kraftwerk";[20] components of this recording were used to create "Like Spinning Plates" on Amnesiac.[3] For Hail to the Thief, the band sought to "get to the core of what's good about the song" and not be distracted by production details or new sounds, settling on a stripped-back arrangement.[3]

Radiohead recorded most of Hail to the Thief in two weeks,[9] with additional recording and mixing at their studio in Oxfordshire, England, in late 2002 and early 2003.[3][21] The guitarist Ed O'Brien told Rolling Stone that Hail to the Thief was the first Radiohead album "where, at the end of making it, we haven't wanted to kill each other".[19] However, mixing and sequencing created conflict; according to Yorke, "There was a long sustained period during which we lived with it but it wasn't completely finished, so you get attached to versions and we had big rows about it."[22] Godrich estimated that rough mixes from the Los Angeles sessions were used for a third of the album.[6]

Lyrics and themes

I was listening to a lot of political programs on BBC Radio 4. I found myself – during that mad caffeine rush in the morning, as I was in the kitchen giving my son his breakfast – writing down little nonsense phrases, those Orwellian euphemisms that [the British and American governments] are so fond of. They became the background of the record. The emotional context of those words had been taken away. What I was doing was stealing it back.

Thom Yorke, Rolling Stone (2003)[2]

The Hail to the Thief lyrics were influenced by what Yorke called "the general sense of ignorance and intolerance and panic and stupidity" following the 2000 election of US president George W. Bush.[21] He took words and phrases from discourse around the unfolding War on Terror and used them in the lyrics and artwork.[2] He denied any intent to make a "political statement" with the songs,[2] but said: "I desperately tried not to write anything political, anything expressing the deep, profound terror I'm living with day to day. But it's just fucking there, and eventually you have to give it up and let it happen."[23]

Yorke, a new father, adopted a strategy of "distilling" the political themes into "childlike simplicity".[21] He took phrases from fairy tales and folklore such as the tale of Chicken Little,[4] and from children's literature and television he shared with his son, such as the 1970s TV series Bagpuss.[3] Parenthood made Yorke concerned about the condition of the world and how it could affect future generations.[24] Greenwood felt Yorke's lyrics expressed "confusion and escape, like 'I'm going to stay at home and look after the people I care about, buy a month's supply of food'."[20]

Yorke also took phrases from Dante's Inferno, the subject of his partner Rachel Owen's PhD thesis.[25] Several songs, such as "2 + 2 = 5", "Sit Down Stand Up", and "Sail to the Moon", reference Christian versions of good and evil and heaven and hell, a first for Radiohead's music.[26] Other songs reference science fiction, horror and fantasy, such as the wolves and vampires of "A Wolf at the Door" and "We Suck Young Blood", the reference to the slogan "2 + 2 = 5" in the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, and the allusion to the giant of Gulliver's Travels in "Go to Sleep".[27]

Title

Radiohead struggled to name the album.[3] They considered titling it The Gloaming (meaning "twilight" or "dusk"), but this was rejected as too "poetic"[28] and "doomy"[2] and so became the album's subtitle.[29] Other titles considered included Little Man Being Erased, The Boney King of Nowhere and Snakes and Ladders, which became the alternative titles for "Go To Sleep", "There There" and "Sit Down. Stand Up".[4][12] The use of alternative titles was inspired by Victorian playbills showcasing moralistic songs played in music halls.[30]

The phrase "hail to the thief" was used by anti-Bush protesters as a play on "Hail to the Chief", the American presidential anthem.[31] Yorke described hearing the phrase for the first time as a "formative moment".[2] Radiohead chose the title partly in reference to Bush,[32] but also in response to "the rise of doublethink and general intolerance and madness ... like individuals were totally out of control of the situation ... a manifestation of something not really human".[3] The title also references the leak of an unfinished version of the album before its release.[30] Yorke worried it might be misconstrued solely as reference to the US election, but his bandmates felt it "conjured up all the nonsense and absurdity and jubilation of the times".[2]

Music

Hail to the Thief incorporates alternative rock,[33] art rock,[34] experimental rock[35] and electronic rock.[36] It features more conventional rock instrumentation and less digital manipulation than Radiohead's previous albums Kid A and Amnesiac; it makes prominent use of live drums, guitar and piano, and Yorke's voice was less manipulated with effects.[3] Rolling Stone said Hail to the Thief was "more tuneful and song-focused".[37] Several tracks use the "Pixies-like" quiet-to-loud building of tension Radiohead had employed on previous albums.[38]

Though Yorke described Hail to the Thief as "very acoustic",[21] he denied that it was a "guitar record".[8] It retains electronic elements such as synthesisers, drum machines and sampling,[39][40] and Yorke and Jonny Greenwood are credited for "laptop".[15] The Spin critic Will Hermes found that Hail to the Thief "seesaws between the chill of sequencers and the warmth of fingers on strings and keys".[39] Radiohead saw Hail to the Thief as a "sparkly, shiny pop record. Clear and pretty."[41] O'Brien felt the album captured a new "swaggering" sound, with "space and sunshine and energy".[19]

The opening track, "2 + 2 = 5" is a rock song that builds to a loud climax.[25] "Sit Down. Stand Up", an electronic song, was influenced by the jazz musician Charles Mingus.[3] "Sail to the Moon" is a lullaby-like piano ballad with shifting time signatures. The lyrics allude to the Biblical story of Noah's Ark,[42] and was written "in five minutes" for Yorke's infant son Noah.[43] "Backdrifts" is an electronic song about "the slide backwards that's happening everywhere you look".[3]

"Go to Sleep" begins with an acoustic guitar riff described by the bassist, Colin Greenwood, as "1960s English sort of folk". "Where I End and You Begin" is a rock song with "walls" of ondes Martenot and rhythm section influenced by New Order.[3] According to Yorke, "We Suck Young Blood" is a "slave ship tune"[12] with a free jazz break, and is "not to be taken seriously".[20] With ill-timed, "zombie-like" handclaps,[44] the song satirises Hollywood culture and its "constant desire to stay young and fleece people, suck their energy".[12]

"The Gloaming" is an electronic song with "mechanical" rhythms that Jonny Greenwood built from tape loops.[3] Greenwood described it as "very old school electronica: no computers, just analogue synths, tape machines, and sellotape".[13] Yorke felt the song was "the most explicit protest song on the record ... I feel really strongly that it's about the rise of fascism, and the rise of intolerance and bigotry and fear, and all the things that keep a population down."[21] "There There" is a rock song with layered percussion that builds to a loud climax. It was influenced by krautrock band Can,[12] Siouxsie and the Banshees[45] and the Pixies.[3][20]

Yorke described "I Will" as "the angriest song I've ever written".[3] Its lyrics were inspired by news footage of the Amiriyah shelter bombing in the Gulf War, which killed about 400 people, including children and families.[12] The funk-influenced "A Punchup at a Wedding" expresses the helplessness Yorke felt in the face of world events, and his anger over a negative review of Radiohead's homecoming performance in South Park, Oxford in 2001.[3] Yorke said the performance was "one of the biggest days in my life", and that "I just didn't understand why... how someone, just because they had access to a keyboard and a typewriter, could just totally write off an event that meant an awful lot to an awful lot of people."[3] For "Myxomatosis", a song built on a driving fuzz bassline,[46] Radiohead sought to recreate the "frightening" detuned synthesiser sounds of 1970s and 80s new wave bands such as Tubeway Army.[3]

Jonny Greenwood described "Scatterbrain" as "very simple and sort of quite pretty, but there's something about the music for me, the chords for me, where it never quite resolves".[3] NME described the final track, "A Wolf at the Door" as "a pretty song, with a sinister monologue over the top of it"; Greenwood likened its lyrics to a Grimms' fairy tale.[20] Yorke described its placement at the end of the album as "sort of like waking you up at the end ... It's all been a nightmare and you need to go and get a glass of water now."[3]

Artwork

The Hail to the Thief's artwork was created by Radiohead's collaborator Stanley Donwood,[5] who joined them during the recording in Hollywood.[5] Donwood initially planned to create artwork based on photographs of phallic topiary, but the idea was rejected by Yorke.[47] Instead, the cover art is a roadmap of Hollywood, with words and phrases taken from roadside advertising in Los Angeles, such as "God", "TV" and "oil".[48] Donwood noted that advertising was designed to be attractive, but that there was something "unsettling" about being sold something; he took the advertising slogans out of context to "remove the imperative" and "get to the pure heart of advertising".[49]

Other words in the artwork were taken from Yorke's lyrics[47] and political discussion surrounding the war on terror.[5] Among them is the phrase "burn the witch", a reference to "Burn the Witch", a song Radiohead worked on during the Hail to the Thief sessions but did not complete until their ninth album, A Moon Shaped Pool (2016).[50]

Comparing the cover to the more subdued palettes of his prior Radiohead artworks, Donwood described the bright, "pleasing" colours as "ominous because all these colours that I've used are derived from the petrol-chemical industry ... We've created this incredibly vibrant society, but we're going to have to deal with the consequences sooner or later."[49]

The essayist Amy Britton interpreted the artwork as an allusion to the Bush administration's "road map for peace" plan for the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[51] Joseph Tate, likening the art to the paintings of French artist Jean Dubuffet, saw it as a "homogenised and heavily regimented" portrayal of "capitalism's glaring visual presence: an oppressive sameness of style and color that mirrors globalization's reduction of difference".[52] Other artworks included with the album refer to cities relevant to the war on terror,[47] including New York, London, Grozny and Baghdad.[53] Early editions contained a fold-out road map of the cover.[5]

Internet leak

On 30 March 2003, ten weeks before release, an unfinished version of Hail to the Thief was leaked online.[54] The leak comprised rough edits and unmixed songs from January that year.[55] On Radiohead's forum, Jonny Greenwood wrote that the band were "pissed off", not with downloaders but because unfinished work had been released "in this sloppy way".[56] Colin Greenwood said the leak was "like being photographed with one sock on when you get out of bed in the morning", but expressed dismay at the cease-and-desist orders sent by label EMI to radio stations and fan sites playing the leaked tracks, saying: "Don't record companies usually pay thousands of dollars to get stations to play their records? Now they're paying money to stations not to play them."[57]

EMI decided against moving the release date earlier to combat the leak. EMI executive Ted Mico said the company was confident that Hail to the Thief would sell and that the leak had brought them additional press.[58] The leak partly influenced Radiohead's decision to self-release their next album, In Rainbows (2007), online, terming it "their leak date".[59]

Release

Hail to the Thief was released on 9 June 2003 by Parlophone Records in the UK and a day later by Capitol Records in the US.[2] The CD was printed with copy protection in some regions; the Belgian consumer group Test-Achats received complaints that it would not play on some CD players.[60] A compilation of Hail to the Thief B-sides, remixes and live performances, Com Lag (2plus2isfive), was released in April 2004.[61]

Hail to the Thief reached number one in the UK Albums Chart and stayed on the chart for 14 weeks,[62] selling 114,320 copies in its first week.[63] In the US, it entered at number three on the Billboard 200, selling 300,000 copies in its first week,[64][65] more than any previous Radiohead album.[66] By 2008, it had sold over a million copies in the US.[67] It is certified platinum in the UK[68] and Canada.[69]

Promotion

According to the Guardian critic Alexis Petridis, Hail to the Thief's marketing campaign was "by [Radiohead] standards ... a promotional blitzkrieg".[70] In April 2003, promotional posters spoofing talent recruitment posters appeared in Los Angeles and London with slogans taken from the lyrics of "We Suck Young Blood". The posters included a phone number spelling the phoneword "to thief", which connected callers to a recording welcoming them to the "Hail to the Thief customer care hotline".[71] In May, planes trailing Hail to the Thief banners flew over the California Coachella Festival.[70]

"There There" was released as the lead single on 26 May 2003.[72] Yorke asked the Bagpuss creator, Oliver Postgate, to create its music video, but Postgate, who was retired, declined.[4] Instead, a stop-motion animated video was created by Chris Hopewell.[73] The video debuted on the Times Square Jumbotron in New York on 20 May 2003, and received hourly play that day on MTV2.[58] "There There" was followed by the singles "Go to Sleep" on 18 August and "2 + 2 = 5" on 17 November.

In June, Radiohead relaunched their website, featuring digital animations on the themes of mass-media culture and 24-hour cities.[74] They also launched radiohead.tv, where short films, music videos and live webcasts from the studio were streamed at scheduled times. Visitors late for streams were shown a test card with "1970s-style" intermission music.[74] Yorke said Radiohead had planned to broadcast the material on their own television channel, but this was cancelled due to "money, cutbacks, too weird, might scare the children, staff layoffs, shareholders".[75] The material was released on the 2004 DVD The Most Gigantic Lying Mouth of All Time.[76]

Critical reception

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 85/100[40] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[78] |

| The Guardian | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| Mojo | |

| NME | 7/10[28] |

| Pitchfork | 9.3/10[42] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin | A[39] |

Hail to the Thief has a score of 85 out of 100 on review aggregate site Metacritic, indicating "universal acclaim".[40] Neil McCormick, writing for The Daily Telegraph, called it "Radiohead firing on all cylinders, a major work by major artists at the height of their powers".[82] Chris Ott of Pitchfork wrote that Radiohead had "largely succeeded in their efforts to shape pop music into as boundless and possible a medium as it should be" and named it the week's "Best New Music".[42] The New York critic Ethan Brown said that Hail to the Thief "isn't a protest album, and that's why it works so well. As with great Radiohead records past, such as Kid A, the music – restlessly, freakishly inventive – pushes politics far into the background."[83] Andy Kellman of AllMusic wrote that "despite the fact that it seems more like a bunch of songs on a disc rather than a singular body, its impact is substantial", concluding that the band "have entered a second decade of record-making with a surplus of momentum".[77] In Mojo, Peter Paphides wrote that Hail to the Thief "coheres as well as anything else in their canon".[80]

James Oldham of NME saw Hail to the Thief as "a good rather than great record... the impact of the best moments is dulled by the inclusion of some indifferent electronic compositions."[28] The Q writer John Harris felt that some of the material "comes dangerously close to being all experimentalism and precious little substance".[81] Alexis Petridis of The Guardian wrote that while "you could never describe Hail to the Thief as a bad record", it was "neither startlingly different and fresh nor packed with the sort of anthemic songs that once made [Radiohead] the world's biggest band". He felt the political lyrics and bleak mood put Radiohead in danger of self-parody.[70] Robert Christgau of The Village Voice wrote that while its melodies and guitar work are "never as elegiac and lyrical" or "articulate and demented" as those of OK Computer, he felt it "flows better"[84] and later awarded it an "honourable mention".[85]

Hail to the Thief was the fifth consecutive Radiohead album nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album,[86] and earned Godrich and engineer Darrell Thorp the 2004 Grammy Award for Best Engineered Non-Classical Album.[87] In 2010, Rolling Stone ranked Hail to the Thief the 89th best album of the 2000s, writing that "the dazzling overabundance of ideas makes Hail to the Thief a triumph".[88]

Legacy

Radiohead have criticised Hail to the Thief. In 2006, Yorke told Spin: "I'd maybe change the playlist. I think we had a meltdown when we put it together ... We wanted to do things quickly, and I think the songs suffered."[89] In 2008, Yorke posted an alternative track listing on Radiohead's website, omitting "Backdrifts", "We Suck Young Blood", "I Will" and "A Punchup at a Wedding".[6] That year, in an interview with Mojo, O'Brien said Radiohead should have cut the album to ten tracks and that its length had alienated some listeners, and Colin Greenwood said several songs were unfinished and that the album was "a holding process".[90] Jonny agreed that the album was too long, and said: "We were trying to do what people said we were good at ... But it was good for our heads. It was good for us to be doing a record that came out of playing live."[90] In 2013, Godrich told NME: "I think there's some great moments on there — but too many songs ... As a whole I think it's charming because of the lack of editing. But personally it's probably my least favourite of all the albums ... It didn't really have its own direction. It was almost like a homogeny of previous work. Maybe that's its strength."[6]

Reissues

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| The A.V. Club | A−[91] |

| Pitchfork | 8.6/10[38] |

After a period of being out of print on vinyl, EMI reissued a double LP of Hail to the Thief on 19 August 2008 along with Kid A, Amnesiac and OK Computer as part of the "From the Capitol Vaults" series.[92]

On 31 August 2009, EMI reissued Hail to the Thief in a 2-CD "Collector's Edition" and a 2-CD 1-DVD "Special Collector's Edition". The first CD contains the original studio album; the second CD collects B-sides and live performances previously compiled on the COM LAG (2plus2isfive) EP (2004); the DVD contains music videos and a live television performance. Radiohead, who left EMI in 2007,[93] had no input into the reissue and the music was not remastered.[94] Pitchfork named the "Collector's Edition" the week's "best new reissue" and "Gagging Order" the best B-side included in the bonus material.[38] The A.V. Club wrote that the bonus content was all "worth hearing, though the live tracks stand out".[91]

The "Collector's Editions" were discontinued after Radiohead's back catalogue was transferred to XL Recordings in 2016.[95] In May 2016, XL reissued Radiohead's back catalogue on vinyl, including Hail to the Thief.[96]

Track listing

All songs written by Radiohead.

- "2 + 2 = 5" ("The Lukewarm.") – 3:19

- "Sit down. Stand up." ("Snakes & Ladders.") – 4:19

- "Sail to the Moon." ("Brush the Cobwebs out of the Sky.") – 4:18

- "Backdrifts" ("Honeymoon is Over.") – 5:22

- "Go to Sleep." ("Little Man being Erased.") – 3:21

- "Where I End and You Begin." ("The Sky Is Falling In.") – 4:29

- "We suck Young Blood." ("Your Time is Up.") – 4:56

- "The Gloaming." (Softly Open our Mouths in the Cold.") – 3:32

- "There there." ("The Boney King of Nowhere.") – 5:25

- "I will." ("No man's Land.") – 1:59

- "A Punchup at a Wedding." ("No no no no no no no no.") – 4:57

- "Myxomatosis." ("Judge, Jury & Executioner.") – 3:52

- "Scatterbrain." ("As Dead as Leaves.") – 3:21

- "A Wolf at the Door." ("It Girl. Rag Doll.") – 3:21

Personnel

Adapted from the Hail to the Thief liner notes.[15]

|

Radiohead

|

Additional personnel

|

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

Certifications

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

Footnotes

- Reynolds, Simon (July 2001). "Walking on Thin Ice". The Wire. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- Fricke, David (27 June 2003). "Bitter prophet: Thom Yorke on Hail to the Thief". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- "Radiohead Hail to the Thief interview CD" (Interview). Parlophone. 22 April 2003. Promotional interview CD sent to British music press.

- Odell, Michael (July 2003). "Silence! Genius at work". Q: 82–93.

- "MAPS AND LEGENDS". NME. 29 April 2003. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- Lucy Jones (7 June 2013). "Hail To The Thief' Is 10 - Revisiting Radiohead's Underrated Masterpiece". NME. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- Radiohead Warm Up". Rolling Stone magazine, 24 May 2002.

- "Exclusive: Thom on new Radiohead album". NME. 5 October 2002.

- Wiederhorn, Jon (19 June 2003). "Radiohead: A New Life". MTV. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- Jonny Greenwood; Thom Yorke (4 June 2003). Launch Media (Interview). New York City.

{{cite interview}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Lyndsey Parker (28 July 2003). "Putting The Music Biz in Its Right Place". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- "Thom Yorke on 'Hail to the Thief'". Xfm London. 2 July 2003. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- Nick Collins. "CMJ Reviews – Radiohead: Kid A, Amnesiac and Hail to the Thief". Computer Music Journal. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- Astley-Brown, Michael (22 February 2017). "Recreate Jonny Greenwood's randomised stutter effect with new Feral Glitch pedal". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Hail to the Thief (booklet). Radiohead. 2003. p. 15.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - Ross, Alex (20 August 2001). "The Searchers: Radiohead's unquiet revolution". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- Martin Anderson (20 May 2010). "Yvonne Loriod: Pianist who became the muse and foremost interpreter of the works of her husband Olivier Messiaen". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- Bonner, Michael (December 2012), "An Audience With ... Jonny Greenwood", Uncut

- Edwards, Gavin (9 May 2003). "Radiohead swagger on Thief". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Robinson, John (10 May 2003). "Bagpuss, ex-lax, and the angriest thing we've ever written". NME: 34–35.

- "Recording 'Hail to the Thief' in Los Angeles". Xfm London. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- Will Self (13 April 2012). "Make rock not war! When Will Self met Thom Yorke". GQ. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- 'Toronto Star', 8 June 2003

- Chuck Klosterman (29 June 2003). "Fitter Happier: Radiohead Return". Spin. Archived from the original on 28 December 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- Lynskey, Dorian (2011). 33 Revolutions per Minute: A History of Protest Songs, from Billie Holiday to Green Day. HarperCollins. p. 519. ISBN 978-0-06-167015-2.

- Tate, pg. 182.

- Forbes, pg. 237.

- Oldham, James (1 May 2003). "Radiohead : Hail To The Thief". NME. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Hail to the Thief (booklet). Radiohead. 2003. p. 8.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - Farber, Jim (4 June 2003). "Radiohead set to steal the show again". The Age. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- Bendat, p.70.

- Yorke, Thom (10 July 2003). Fast Forward (Interview). Interviewed by Charlotte Roche. Viva.

{{cite interview}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Kreativ Sound. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- Harvilla, Rob (25 September 2003). "Radiohead Rorschach". Houston Press. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "Radiohead - Hail to the Thief". Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Lecaro, Lina (6 May 2004). "Coachella 2004". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Touré (3 June 2003). "Hail to the Thief". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Tangari, Joe (27 August 2009). "Radiohead: Hail to the Thief: Special Collectors Edition". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Hermes, Will (July 2003). "Steal This Laptop". Spin. 19 (7): 103–04. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- "Reviews for Hail to the Thief by Radiohead". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- NME, 3 May 2003, p.27.

- Ott, Chris (9 June 2003). "Radiohead: Hail to the Thief". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Tate, pg. 183.

- Forbes

- "Radiohead Biography". capitolmusic.ca. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

Colin Greenwood remembers: "The first single we're releasing is actually the longest song on the record. ("There There"). It was all recorded live in Oxford. We all got excited at the end because Nigel was trying to get Jonny to play like John McGeoch in Siouxsie and the Banshees."

- Robbins, Ira and Wilson Neate and Jason Reeher. "Radiohead". Trouser Press. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "The Untold Stories behind Radiohead's Album Covers". Monster Children. 8 November 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Radiohead's 'sixth man' reveals the secrets behind their covers". The Guardian. 22 November 2006. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- Dombal, Ryan (15 September 2010), "Take Cover: Radiohead Artist Stanley Donwood", Pitchfork, archived from the original on 30 August 2011, retrieved 19 September 2011

- Yoo, Noah; Monroe, Jazz (3 May 2016). "Watch Radiohead's Video for New Song 'Burn the Witch'". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- Britton, pg. 329.

- Tate, pg. 179.

- Tate, p.178.

- "Radiohead tracks appear on web". BBC. 2 April 2003. Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- Sedgewick, Augustin K. (3 April 2003). "Radiohead Tracks Thieved". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Andy Frankowski (3 April 2003). "Hail to the Thief: Leaked tracks are stolen early recordings". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- "It's all fucked". Q: 20–21. June 2003.

- Cohen, Jonathan (14 June 2003). "Web Leak Fails to Deter Capitol's Radiohead Setup". Billboard.

- "The way we termed it was "our leak date." Every record for the last four – including my solo record – has been leaked. So the idea was like, we'll leak it, then." Byrne, David (18 December 2007). "David Byrne and Thom Yorke on the Real Value of Music". Wired. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- "Consumers sue over anti-copy CDs". BBC. 6 January 2004. Archived from the original on 14 April 2004. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- Allmusic review

- "Radiohead – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "Sales shape up with Dido in charge". Music Week. 11 October 2003. p. 23.

- Jeff Leeds (10 January 2008). "Radiohead Finds Sales, Even After Downloads". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Radiohead finds pot of gold in America". Stuff.co.nz. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Ailing Vandross Dances Atop Album Chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- "Radiohead album crowns US chart". BBC. 10 January 2008. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "BPI – Certified Awards Search". British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on 24 September 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2012. Note: reader must define search parameter as "Radiohead".

- "Gold Platinum Database: Radiohead". Canadian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Petridis, Alexis (6 June 2003). "CD: Radiohead: Hail to the Thief". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "Radiohead spoof talent shows". BBC. 7 May 2003. Archived from the original on 14 April 2004. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- "'THERE THERE', THERE'S MORE!". NME. 1 May 2003. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- McLean, Craig (16 May 2003). "OK, no computers". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Radiohead TV goes on air". BBC. 10 June 2003. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- "Yes I am entering Miss World". The Guardian. 21 November 2003. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- Modell, Josh (27 December 2004). "Radiohead: The Most Gigantic Lying Mouth Of All Time". Music. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Kellman, Andy. "Hail to the Thief – Radiohead". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Brunner, Rob (6 June 2003). "Hail to the Thief". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- Cromelin, Richard (8 June 2003). "Don't settle in -- this music demands attention". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- Paphides, Peter (June 2003). "Unite and take over". Mojo (115): 90.

- Harris, John (July 2003). "Weird Science". Q (204): 98.

- McCormick, Neil (7 June 2003). "CD of the week: firing on all cylinders". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Ethan Brown (16 June 2003). "Radioheadline". New York. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Christgau, Robert (8 July 2003). "No Hope Radio". The Village Voice. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Christgau, Robert. "Radiohead: Hail to the Thief". RobertChristgau.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Holly Frith (9 January 2012). "Two New Radiohead Tracks Posted Online – Listen". Gigwise. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "Past Winners Search". Grammy.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "100 Best Albums of the 2000s: Radiohead, "Hail to the Thief"". Rolling Stone. 18 July 2011. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- "Ain't No Fat on This Record". Spin, August 2006.

- Paytress, Mark (February 2008), "Chasing rainbows", Mojo, vol. 171, pp. 74–85

- Phipps, Keith (1 September 2009). "Radiohead: Kid A / Amnesiac / Hail To The Thief (Deluxe Editions)". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- "Coldplay, Radiohead to be reissued on vinyl", NME, 10 July 2008, archived from the original on 16 February 2012, retrieved 2 November 2011

- Sherwin, Adam (28 December 2007). "EMI accuses Radiohead after group's demands for more fell on deaf ears". The Times. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- McCarthy, Sean (18 December 2009). "The Best Re-Issues of 2009: 18: Radiohead: Pablo Honey / The Bends / OK Computer / Kid A / Amnesiac / Hail to the Thief". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 20 December 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Christman, Ed (4 April 2016). "Radiohead's Early Catalog Moves From Warner Bros. to XL". Billboard. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Spice, Anton (6 May 2016). "Radiohead to reissue entire catalogue on vinyl". thevinylfactory.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "Australiancharts.com – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Austriancharts.at – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Ultratop.be – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Ultratop.be – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Radiohead Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Danishcharts.dk – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Dutchcharts.nl – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Radiohead: Hail To The Thief" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Lescharts.com – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Offiziellecharts.de – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Irish-charts.com – Discography Radiohead". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Italiancharts.com – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Charts.nz – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Norwegiancharts.com – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Official Retail Sales Chart". Polish Music Charts. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- "Portuguesecharts.com – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Top National Sellers: Spain" (PDF). Music & Media. 28 June 2003. p. 14.

- "Swedishcharts.com – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Swisscharts.com – Radiohead – Hail To The Thief". Hung Medien. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Radiohead Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "ARIA Top 100 Albums for 2003". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Jaaroverzichten 2003". Ultratop. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Rapports Annuels 2003". Ultratop. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Jaaroverzichten – Album 2003". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Top de l'année Top Albums 2003" (in French). SNEP. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 2003". hitparade.ch. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2003". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- "Billboard 200 - 2003 Year-end chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2006 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 2007". Ultratop. Hung Medien.

- "Canadian album certifications – Radioehad – Hail to the Thief". Music Canada.

- "French album certifications – Radiohead – Hail to the Thief" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique.

- "Japanese album certifications – レディオヘッド – ヘイル・トゥ・ザ・シーフ" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved 30 August 2022. Select 2003年8月 on the drop-down menu

- "New Zealand album certifications – Radiohead – Hail to the Thief". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards (Radiohead; 'Hail to the Thief')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- "British album certifications – Radiohead – Hail to the Thief". British Phonographic Industry.

- "American album certifications – Radiohead – Hail to the thief". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- DeSantis, Nick (10 May 2016). "Radiohead's Digital Album Sales, Visualized". forbes.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 2014". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

Sources

- Bendat, Jim. Democracy's Big Day: The Inauguration of our President 1789–2009. iUniverse Star, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58348-466-1.

- Britton, Amy. Revolution Rock: The Albums Which Defined Two Ages. AuthorHouse, 2011. ISBN 1-4678-8710-2.

- Forbes, Brandon W. Radiohead and Philosophy: Fitter Happier More Deductive. Open Court, 2009. ISBN 0-8126-9664-6

- Tate, Joseph. The Music and Art of Radiohead. Ashgate Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-0-7546-3980-0.

External links

- Official Radiohead website

- Hail to the Thief at Discogs (list of releases)