Inferno (Dante)

Inferno (Italian: [iɱˈfɛrno]; Italian for "Hell") is the first part of Italian writer Dante Alighieri's 14th-century epic poem Divine Comedy. It is followed by Purgatorio and Paradiso. The Inferno describes Dante's journey through Hell, guided by the ancient Roman poet Virgil. In the poem, Hell is depicted as nine concentric circles of torment located within the Earth; it is the "realm ... of those who have rejected spiritual values by yielding to bestial appetites or violence, or by perverting their human intellect to fraud or malice against their fellowmen".[1]

As an allegory, the Divine Comedy represents the journey of the soul toward God, with the Inferno describing the recognition and rejection of sin.[2]

Prelude to Hell

Canto I

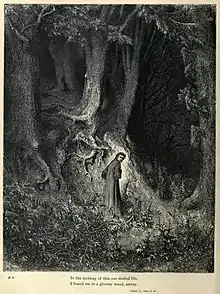

The poem begins on the night of Maundy Thursday on March 24 (or April 7), 1300, shortly before the dawn of Good Friday.[3][4] The narrator, Dante himself, is thirty-five years old, and thus "midway in the journey of our life" (Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita[5]) – half of the biblical lifespan of seventy (Psalm 89:10, Vulgate; Psalm 90:10, KJV). The poet finds himself lost in a dark wood (selva oscura[6]), astray from the "straight way" (diritta via,[7] also translatable as "right way") of salvation. He sets out to climb directly up a small mountain, but his way is blocked by three beasts he cannot evade: a lonza[8] (usually rendered as "leopard" or "leopon"),[9] a leone[10] (lion), and a lupa[11] (she-wolf). The three beasts, taken from Jeremiah 5:6, are thought to symbolize the three kinds of sin that bring the unrepentant soul into one of the three major divisions of Hell. According to John Ciardi, these are incontinence (the she-wolf); violence and bestiality (the lion); and fraud and malice (the leopard);[12] Dorothy L. Sayers assigns the leopard to incontinence and the she-wolf to fraud/malice.[13] It is now dawn of Good Friday, April 8, with the sun rising in Aries. The beasts drive him back despairing into the darkness of error, a "lower place" (basso loco[14]) where the sun is silent (l sol tace[15]). However, Dante is rescued by a figure who announces that he was born sub Iulio[16] (i.e., in the time of Julius Caesar) and lived under Augustus: it is the shade of the Roman poet Virgil, author of the Aeneid, a Latin epic.

Canto II

On the evening of Good Friday, Dante hesitates as he follows Virgil; Virgil explains that he has been sent by Beatrice, the symbol of Divine Love. Beatrice had been moved to aid Dante by the Virgin Mary (symbolic of compassion) and Saint Lucia (symbolic of illuminating Grace). Rachel, symbolic of the contemplative life, also appears in the heavenly scene recounted by Virgil. The two of them then begin their journey to the underworld.

Canto III: Vestibule of Hell

Dante passes through the gate of Hell, which bears an inscription ending with the famous phrase "Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch'intrate",[17] most frequently translated as "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here."[nb 1] Dante and his guide hear the anguished screams of the Uncommitted. These are the souls of people who in life took no sides; the opportunists who were for neither good nor evil, but instead were merely concerned with themselves. Among these Dante recognizes a figure who made the "great refusal," implied to be Pope Celestine V, whose "cowardice (in selfish terror for his own welfare) served as the door through which so much evil entered the Church".[18] Mixed with them are outcasts who took no side in the Rebellion of Angels. These souls are forever unclassified; they are neither in Hell nor out of it, but reside on the shores of the Acheron. Naked and futile, they race around through the mist in eternal pursuit of an elusive, wavering banner (symbolic of their pursuit of ever-shifting self-interest) while relentlessly chased by swarms of wasps and hornets, who continually sting them.[19] Loathsome maggots and worms at the sinners' feet drink the putrid mixture of blood, pus, and tears that flows down their bodies. This symbolizes the sting of their guilty conscience and the repugnance of sin. This may also be seen as a reflection of the spiritual stagnation in which they lived.

.jpg.webp)

After passing through the vestibule, Dante and Virgil reach the ferry that will take them across the river Acheron and to Hell proper. The ferry is piloted by Charon, who does not want to let Dante enter, for he is a living being. Virgil forces Charon to take him by declaring, Vuolsi così colà dove si puote / ciò che si vuole ("It is so willed there where is power to do / That which is willed"),[20] referring to the fact that Dante is on his journey on divine grounds. The wailing and blasphemy of the damned souls entering Charon's boat contrast with the joyful singing of the blessed souls arriving by ferry in the Purgatorio. The passage across the Acheron, however, is undescribed, since Dante faints and does not awaken until they reach the other side.

Nine circles of Hell

Overview

Virgil proceeds to guide Dante through the nine circles of Hell. The circles are concentric, representing a gradual increase in wickedness, and culminating at the centre of the earth, where Satan is held in bondage. The sinners of each circle are punished for eternity in a fashion fitting their crimes: each punishment is a contrapasso, a symbolic instance of poetic justice. For example, later in the poem, Dante and Virgil encounter fortune-tellers who must walk forward with their heads on backward, unable to see what is ahead, because they tried to see the future through forbidden means. Such a contrapasso "functions not merely as a form of divine revenge, but rather as the fulfilment of a destiny freely chosen by each soul during his or her life".[21] People who sinned, but prayed for forgiveness before their deaths are found not in Hell but in Purgatory, where they labour to become free of their sins. Those in Hell are people who tried to justify their sins and are unrepentant.

Dante's Hell is structurally based on the ideas of Aristotle, but with "certain Christian symbolisms, exceptions, and misconstructions of Aristotle's text",[22] and a further supplement from Cicero's De Officiis.[23] Virgil reminds Dante (the character) of "Those pages where the Ethics tells of three / Conditions contrary to Heaven's will and rule / Incontinence, vice, and brute bestiality".[24] Cicero, for his part, had divided sins between Violence and Fraud.[25] By conflating Cicero's violence with Aristotle's bestiality, and his fraud with malice or vice, Dante the poet obtained three major categories of sin, as symbolized by the three beasts that Dante encounters in Canto I: these are Incontinence, Violence/Bestiality, and Fraud/Malice.[22][26] Sinners punished for incontinence (also known as wantonness) – the lustful, the gluttonous, the hoarders and wasters, and the wrathful and sullen – all demonstrated weakness in controlling their appetites, desires, and natural urges; according to Aristotle's Ethics, incontinence is less condemnable than malice or bestiality, and therefore these sinners are located in four circles of Upper Hell (Circles 2–5). These sinners endure lesser torments than do those consigned to Lower Hell, located within the walls of the City of Dis, for committing acts of violence and fraud – the latter of which involves, as Dorothy L. Sayers writes, "abuse of the specifically human faculty of reason".[26] The deeper levels are organized into one circle for violence (Circle 7) and two circles for fraud (Circles 8 and 9). As a Christian, Dante adds Circle 1 (Limbo) to Upper Hell and Circle 6 (Heresy) to Lower Hell, making 9 Circles in total; incorporating the Vestibule of the Futile, this leads to Hell containing 10 main divisions.[26] This "9+1=10" structure is also found within the Purgatorio and Paradiso. Lower Hell is further subdivided: Circle 7 (Violence) is divided into three rings, Circle 8 (Fraud) is divided into ten bolge, and Circle 9 (Treachery) is divided into four regions. Thus, Hell contains, in total, 24 divisions.

First Circle (Limbo)

Canto IV

Dante wakes up to find that he has crossed the Acheron, and Virgil leads him to the first circle of the abyss, Limbo, where Virgil himself resides. The first circle contains the unbaptized and the virtuous pagans, who, although not sinful enough to warrant damnation, did not accept Christ. Dorothy L. Sayers writes, "After those who refused choice come those without opportunity of choice. They could not, that is, choose Christ; they could, and did, choose human virtue, and for that they have their reward."[27] Limbo shares many characteristics with the Asphodel Meadows, and thus, the guiltless damned are punished by living in a deficient form of Heaven. Without baptism ("the portal of the faith that you embrace"[28]) they lacked the hope for something greater than rational minds can conceive. When Dante asked if anyone has ever left Limbo, Virgil states that he saw Jesus ("a Mighty One") descend into Limbo and take Adam, Abel, Noah, Moses, Abraham, David, Rachel, and others (see Limbo of the Patriarchs) into his all-forgiving arms and transport them to Heaven as the first human souls to be saved. The event, known as the Harrowing of Hell, supposedly occurred around AD 33 or 34.

Dante encounters the poets Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan, who include him in their number and make him "sixth in that high company".[29] They reach the base of a great Castle – the dwelling place of the wisest men of antiquity – surrounded by seven gates, and a flowing brook. After passing through the seven gates, the group comes to an exquisite green meadow and Dante encounters the inhabitants of the Citadel. These include figures associated with the Trojans and their descendants (the Romans): Electra (mother of Troy's founder Dardanus), Hector, Aeneas, Julius Caesar in his role as Roman general ("in his armor, falcon-eyed"),[30] Camilla, Penthesilea (Queen of the Amazons), King Latinus and his daughter, Lavinia, Lucius Junius Brutus (who overthrew Tarquin to found the Roman Republic), Lucretia, Julia, Marcia, and Cornelia Africana. Dante also sees Saladin, a Muslim military leader known for his battle against the Crusaders, as well as his generous, chivalrous, and merciful conduct.

Dante next encounters a group of philosophers, including Aristotle with Socrates and Plato at his side, as well as Democritus, "Diogenes" (either Diogenes the Cynic or Diogenes of Apollonia), Anaxagoras, Thales, Empedocles, Heraclitus, and "Zeno" (either Zeno of Elea or Zeno of Citium). He sees the scientist Dioscorides, the mythical Greek poets Orpheus and Linus, and Roman statesmen Marcus Tullius Cicero and Seneca. Dante sees the Alexandrian geometer Euclid and Ptolemy, the Alexandrian astronomer and geographer, as well as the physicians Hippocrates and Galen. He also encounters Avicenna, a Persian polymath, and Averroes, a medieval Andalusian polymath known for his commentaries on Aristotle's works. Dante and Virgil depart from the four other poets and continue their journey.

Although Dante implies that all virtuous non-Christians find themselves here, he later encounters two (Cato of Utica and Statius) in Purgatory and two (Trajan and Ripheus) in Heaven. In Purg. XXII, Virgil names several additional inhabitants of Limbo who were not mentioned in the Inferno.[31]

Second Circle (Lust)

Canto V

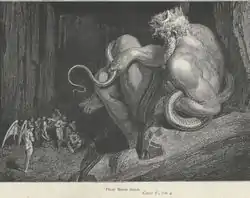

Dante and Virgil leave Limbo and enter the Second Circle – the first of the circles of Incontinence – where the punishments of Hell proper begin. It is described as "a part where no thing gleams".[32] They find their way hindered by the serpentine Minos, who judges all of those condemned for active, deliberately willed sin to one of the lower circles. At this point in Inferno, every soul is required to confess all of their sins to Minos after which Minos sentences each soul to its torment by wrapping his tail around himself a number of times corresponding to the number of the circle of hell to which the soul must go. The role of Minos here is a combination of his classical role as condemner and unjust judge of the underworld and the role of classical Rhadamanthus, interrogator and confessor of the underworld.[33] This mandatory confession makes it so every soul verbalizes and sanctions their own ranking amongst the condemned since these confessions are the sole grounds for their placement in hell.[34] Dante is not forced to make this confession; instead, Virgil rebukes Minos, and he and Dante continue on.

In the second circle of Hell are those overcome by lust. These "carnal malefactors"[35] are condemned for allowing their appetites to sway their reason. These souls are buffeted back and forth by the terrible winds of a violent storm, without rest. This symbolizes the power of lust to blow needlessly and aimlessly: "as the lovers drifted into self-indulgence and were carried away by their passions, so now they drift for ever. The bright, voluptuous sin is now seen as it is – a howling darkness of helpless discomfort."[36] Since lust involves mutual indulgence and is not, therefore, completely self-centered, Dante deems it the least heinous of the sins and its punishment is the most benign within Hell proper.[36][37] The "ruined slope"[38] in this circle is thought to be a reference to the earthquake that occurred after the death of Christ.[39]

In this circle, Dante sees Semiramis, Dido, Cleopatra, Helen of Troy, Paris, Achilles, Tristan, and many others who were overcome by sexual love during their life. Due to the presence of so many rulers among the lustful, the fifth Canto of Inferno has been called the "canto of the queens".[40] Dante comes across Francesca da Rimini, who married the deformed Giovanni Malatesta (also known as "Gianciotto") for political purposes but fell in love with his younger brother Paolo Malatesta; the two began to carry on an adulterous affair. Sometime between 1283 and 1286, Giovanni surprised them together in Francesca's bedroom and violently stabbed them both to death. Francesca explains:

Love, which in gentlest hearts will soonest bloom

seized my lover with passion for that sweet body

from which I was torn unshriven to my doom.

Love, which permits no loved one not to love,

took me so strongly with delight in him

that we are one in Hell, as we were above.

Love led us to one death. In the depths of Hell

Caïna waits for him who took our lives."

This was the piteous tale they stopped to tell.[41]

Francesca further reports that she and Paolo yielded to their love when reading the story of the adultery between Lancelot and Guinevere in the Old French romance Lancelot du Lac. Francesca says, "Galeotto fu 'l libro e chi lo scrisse".[42] The word "Galeotto" means "pander" but is also the Italian term for Gallehaut, who acted as an intermediary between Lancelot and Guinevere, encouraging them on to love. John Ciardi renders line 137 as "That book, and he who wrote it, was a pander."[43] Inspired by Dante, author Giovanni Boccaccio invoked the name Prencipe Galeotto in the alternative title to The Decameron, a 14th-century collection of novellas. Ultimately, Francesca never makes a full confession to Dante. Rather than admit to her and Paolo's sins, the very reasons they reside in this circle of hell, she consistently takes an erroneously passive role in the adulterous affair. The English poet John Keats, in his sonnet "On a Dream", imagines what Dante does not give us, the point of view of Paolo:

... But to that second circle of sad hell,

Where 'mid the gust, the whirlwind, and the flaw

Of rain and hail-stones, lovers need not tell

Their sorrows. Pale were the sweet lips I saw,

Pale were the lips I kiss'd, and fair the form

I floated with, about that melancholy storm.[44]

As he did at the end of Canto III, Dante – overcome by pity and anguish – describes his swoon: "I fainted, as if I had met my death. / And then I fell as a dead body falls".[45]

Third Circle (Gluttony)

Canto VI

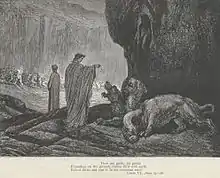

In the third circle, the gluttonous wallow in a vile, putrid slush produced by a ceaseless, foul, icy rain – "a great storm of putrefaction"[46] – as punishment for subjecting their reason to a voracious appetite. Cerberus (described as "il gran vermo", literally "the great worm", line 22), the monstrous three-headed beast of Hell, ravenously guards the gluttons lying in the freezing mire, mauling and flaying them with his claws as they howl like dogs. Virgil obtains safe passage past the monster by filling its three mouths with mud.

Dorothy L. Sayers writes that "the surrender to sin which began with mutual indulgence leads by an imperceptible degradation to solitary self-indulgence".[47] The gluttons grovel in the mud by themselves, sightless and heedless of their neighbors, symbolizing the cold, selfish, and empty sensuality of their lives.[47] Just as lust has revealed its true nature in the winds of the previous circle, here the slush reveals the true nature of sensuality – which includes not only overindulgence in food and drink, but also other kinds of addiction.[48]

In this circle, Dante converses with a Florentine contemporary identified as Ciacco, which means "hog".[49] A character with the same nickname later appears in The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio, where his gluttonous behaviour is clearly portrayed.[50] Ciacco speaks to Dante regarding strife in Florence between the "White" and "Black" Guelphs, which developed after the Guelph/Ghibelline strife ended with the complete defeat of the Ghibellines. In the first of several political prophecies in the Inferno, Ciacco "predicts" the expulsion of the White Guelphs (Dante's party) from Florence by the Black Guelphs, aided by Pope Boniface VIII, which marked the start of Dante's long exile from the city. These events occurred in 1302, prior to when the poem was written but in the future at Easter time of 1300, the time in which the poem is set.[49]

Fourth Circle (Greed)

.jpg.webp)

Canto VII

The Fourth Circle is guarded by a figure Dante names as Pluto: this is Plutus, the deity of wealth in classical mythology. Although the two are often conflated, he is a distinct figure from Pluto (Dis), the classical ruler of the underworld.[nb 2] At the start of Canto VII, he menaces Virgil and Dante with the cryptic phrase Pape Satàn, pape Satàn aleppe, but Virgil protects Dante from him.

Those whose attitude toward material goods deviated from the appropriate mean are punished in the fourth circle. They include the avaricious or miserly (including many "clergymen, and popes and cardinals"),[51] who hoarded possessions, and the prodigal, who squandered them. The hoarders and spendthrifts joust, using great weights as weapons that they push with their chests:

Here, too, I saw a nation of lost souls,

far more than were above: they strained their chests

against enormous weights, and with mad howls

rolled them at one another. Then in haste

they rolled them back, one party shouting out:

"Why do you hoard?" and the other: "Why do you waste?"[52]

Relating this sin of incontinence to the two that preceded it (lust and gluttony), Dorothy L. Sayers writes, "Mutual indulgence has already declined into selfish appetite; now, that appetite becomes aware of the incompatible and equally selfish appetites of other people. Indifference becomes mutual antagonism, imaged here by the antagonism between hoarding and squandering."[53] The contrast between these two groups leads Virgil to discourse on the nature of Fortune, who raises nations to greatness and later plunges them into poverty, as she shifts, "those empty goods from nation unto nation, clan to clan".[54] This speech fills what would otherwise be a gap in the poem, since both groups are so absorbed in their activity that Virgil tells Dante that it would be pointless to try to speak to them – indeed, they have lost their individuality and been rendered "unrecognizable".[55]

Fifth Circle (Wrath)

.jpg.webp)

In the swampy, stinking waters of the river Styx – the Fifth Circle – the actively wrathful fight each other viciously on the surface of the slime, while the sullen (the passively wrathful) lie beneath the water, withdrawn, "into a black sulkiness which can find no joy in God or man or the universe".[53] At the surface of the foul Stygian marsh, Dorothy L. Sayers writes, "the active hatreds rend and snarl at one another; at the bottom, the sullen hatreds lie gurgling, unable even to express themselves for the rage that chokes them".[53] As the last circle of Incontinence, the "savage self-frustration" of the Fifth Circle marks the end of "that which had its tender and romantic beginnings in the dalliance of indulged passion".[53]

Canto VIII

Phlegyas reluctantly transports Dante and Virgil across the Styx in his skiff. On the way they are accosted by Filippo Argenti, a Black Guelph from the prominent Adimari family. Little is known about Argenti, although Giovanni Boccaccio describes an incident in which he lost his temper; early commentators state that Argenti's brother seized some of Dante's property after his exile from Florence.[56] Just as Argenti enabled the seizing of Dante's property, he himself is "seized" by all the other wrathful souls.

When Dante responds "In weeping and in grieving, accursed spirit, may you long remain,"[57] Virgil blesses him with words used to describe Christ himself (Luke 11:27). Literally, this reflects the fact that souls in Hell are eternally fixed in the state they have chosen, but allegorically, it reflects Dante's beginning awareness of his own sin.[58]

Entrance to Dis

In the distance, Dante perceives high towers that resemble fiery red mosques. Virgil informs him that they are approaching the City of Dis. Dis, itself surrounded by the Stygian marsh, contains Lower Hell within its walls.[59] Dis is one of the names of Pluto, the classical king of the underworld, in addition to being the name of the realm. The walls of Dis are guarded by fallen angels. Virgil is unable to convince them to let Dante and him enter.

Canto IX

Dante is threatened by the Furies (consisting of Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone) and Medusa. An angel sent from Heaven secures entry for the poets, opening the gate by touching it with a wand, and rebukes those who opposed Dante. Allegorically, this reveals the fact that the poem is beginning to deal with sins that philosophy and humanism cannot fully understand. Virgil also mentions to Dante how Erichtho sent him down to the lowest circle of Hell to bring back a spirit from there.[58]

Sixth Circle (Heresy)

Canto X

In the sixth circle, heretics, such as Epicurus and his followers (who say "the soul dies with the body")[60] are trapped in flaming tombs. Dante holds discourse with a pair of Epicurian Florentines in one of the tombs: Farinata degli Uberti, a famous Ghibelline leader (following the Battle of Montaperti in September 1260, Farinata strongly protested the proposed destruction of Florence at the meeting of the victorious Ghibellines; he died in 1264 and was posthumously condemned for heresy in 1283); and Cavalcante de' Cavalcanti, a Guelph who was the father of Dante's friend and fellow poet, Guido Cavalcanti. The political affiliation of these two men allows for a further discussion of Florentine politics. In response to a question from Dante about the "prophecy" he has received, Farinata explains that what the souls in Hell know of life on earth comes from seeing the future, not from any observation of the present. Consequently, when "the portal of the future has been shut",[61] it will no longer be possible for them to know anything. Farinata explains that also crammed within the tomb are Emperor Frederick II, commonly reputed to be an Epicurean, and Ottaviano degli Ubaldini, whom Dante refers to as il Cardinale.

Canto XI

Dante reads an inscription on one of the tombs indicating it belongs to Pope Anastasius II – although some modern scholars hold that Dante erred in the verse mentioning Anastasius ("Anastasio papa guardo, / lo qual trasse Fotin de la via dritta", lines 8–9), confusing the pope with the Byzantine emperor of the time, Anastasius I.[62][63][64][65] Pausing for a moment before the steep descent to the foul-smelling seventh circle, Virgil explains the geography and rationale of Lower Hell, in which the sins of violence (or bestiality) and fraud (or malice) are punished. In his explanation, Virgil refers to the Nicomachean Ethics and the Physics of Aristotle, with medieval interpretations. Virgil asserts that there are only two legitimate sources of wealth: natural resources ("Nature") and human labor and activity ("Art"). Usury, to be punished in the next circle, is therefore an offence against both; it is a kind of blasphemy, since it is an act of violence against Art, which is the child of Nature, and Nature derives from God.[66]

Virgil then indicates the time through his unexplained awareness of the stars' positions. The "Wain", the Great Bear, now lies in the northwest over Caurus (the northwest wind). The constellation Pisces (the Fish) is just appearing over the horizon: it is the zodiacal sign preceding Aries (the Ram). Canto I notes that the sun is in Aries, and since the twelve zodiac signs rise at two-hour intervals, it must now be about two hours prior to sunrise: 4:00 AM on Holy Saturday, April 9.[66][67]

Seventh Circle (Violence)

Canto XII

The Seventh Circle, divided into three rings, houses the Violent. Dante and Virgil descend a jumble of rocks that had once formed a cliff to reach the Seventh Circle from the Sixth Circle, having first to evade the Minotaur (L'infamia di Creti, "the infamy of Crete", line 12); at the sight of them, the Minotaur gnaws his flesh. Virgil assures the monster that Dante is not its hated enemy, Theseus. This causes the Minotaur to charge them as Dante and Virgil swiftly enter the seventh circle. Virgil explains the presence of shattered stones around them: they resulted from the great earthquake that shook the earth at the moment of Christ's death (Matt. 27:51), at the time of the Harrowing of Hell. Ruins resulting from the same shock were previously seen at the beginning of Upper Hell (the entrance of the Second Circle, Canto V).

Ring 1: Against Neighbors: In the first round of the seventh circle, the murderers, war-makers, plunderers, and tyrants are immersed in Phlegethon, a river of boiling blood and fire. Ciardi writes, "as they wallowed in blood during their lives, so they are immersed in the boiling blood forever, each according to the degree of his guilt".[69] The Centaurs, commanded by Chiron and Pholus, patrol the ring, shooting arrows into any sinners who emerge higher out of the boiling blood than each is allowed. The centaur Nessus guides the poets along Phlegethon and points out Alexander the Great (disputed), "Dionysius" (either Dionysius I or Dionysius II, or both; they were bloodthirsty, unpopular tyrants of Sicily), Ezzelino III da Romano (the cruelest of the Ghibelline tyrants), Obizzo d'Este, and Guy de Montfort. The river grows shallower until it reaches a ford, after which it comes full circle back to the deeper part where Dante and Virgil first approached it; immersed here are tyrants including Attila, King of the Huns (flagello in terra, "scourge on earth", line 134), "Pyrrhus" (either the bloodthirsty son of Achilles or King Pyrrhus of Epirus), Sextus, Rinier da Corneto, and Rinier Pazzo. After bringing Dante and Virgil to the shallow ford, Nessus leaves them to return to his post. This passage may have been influenced by the early medieval Visio Karoli Grossi.[nb 3]

Canto XIII

Ring 2: Against Self: The second round of the seventh circle is the Wood of the Suicides, in which the souls of the people who attempted or died by suicide are transformed into gnarled, thorny trees and then fed upon by Harpies, hideous clawed birds with the faces of women; the trees are only permitted to speak when broken and bleeding. Dante breaks a twig off one of the trees and from the bleeding trunk hears the tale of Pietro della Vigna, a powerful minister of Emperor Frederick II until he fell out of favor and was imprisoned and blinded. He subsequently committed suicide; his presence here, rather than in the Ninth Circle, indicates that Dante believes that the accusations made against him were false.[70] The Harpies and the characteristics of the bleeding bushes are based on Book 3 of the Aeneid. According to Dorothy L. Sayers, Dante presents the sin of suicide as an "insult to the body; so, here, the shades are deprived of even the semblance of the human form. As they refused life, they remain fixed in a dead and withered sterility. They are the image of the self-hatred which dries up the very sap of energy and makes all life infertile."[70] The trees can also be interpreted as a metaphor for the state of mind in which suicide is committed.[71]

Dante learns that these suicides, unique among the dead, will not be corporally resurrected after the Final Judgement since they threw their bodies away; instead, they will maintain their bushy form, with their own corpses hanging from the thorny limbs. After Pietro della Vigna finishes his story, Dante notices two shades (Lano da Siena and Jacopo Sant' Andrea) race through the wood, chased and savagely mauled by ferocious bitches – this is the punishment of the violently profligate who, "possessed by a depraved passion ... dissipated their goods for the sheer wanton lust of wreckage and disorder".[70] The destruction wrought upon the wood by the profligates' flight and punishment as they crash through the undergrowth causes further suffering to the suicides, who cannot move out of the way.

Canto XIV

Ring 3: Against God, Art, and Nature: The third round of the seventh circle is a great Plain of Burning Sand scorched by great flakes of flame falling slowly down from the sky, an image derived from the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen. 19:24). The Blasphemers (the Violent against God) are stretched supine upon the burning sand, the Sodomites (the Violent against Nature) run in circles, while the Usurers (the Violent against Art, which is the Grandchild of God, as explained in Canto XI) crouch huddled and weeping. Ciardi writes, "Blasphemy, sodomy, and usury are all unnatural and sterile actions: thus the unbearing desert is the eternity of these sinners; and thus the rain, which in nature should be fertile and cool, descends as fire".[72] Dante finds Capaneus stretched out on the sands; for blasphemy against Jove, he was struck down with a thunderbolt during the war of the Seven against Thebes; he is still scorning Jove in the afterlife. The overflow of Phlegethon, the river of blood from the first ring, flows boiling through the Wood of the Suicides (the second ring) and crosses the Burning Plain. Virgil explains the origin of the rivers of Hell, which includes references to the Old Man of Crete.

Canto XV

Protected by the powers of the boiling rivulet, Dante and Virgil progress across the burning plain. They pass a roving group of Sodomites, and Dante, to his surprise, recognizes Brunetto Latini. Dante addresses Brunetto with deep and sorrowful affection, "paying him the highest tribute offered to any sinner in the Inferno",[73] thus refuting suggestions that Dante only placed his enemies in Hell.[74] Dante has great respect for Brunetto and feels spiritual indebtedness to him and his works ("you taught me how man makes himself eternal; / and while I live, my gratitude for that / must always be apparent in my words");[75] Brunetto prophesies Dante's bad treatment by the Florentines. He also identifies other sodomites, including Priscian, Francesco d'Accorso, and Bishop Andrea de' Mozzi.

Canto XVI

The Poets begin to hear the waterfall that plunges over the Great Cliff into the Eighth Circle when three shades break from their company and greet them. They are Iacopo Rusticucci, Guido Guerra, and Tegghiaio Aldobrandi – all Florentines much admired by Dante. Rusticucci blames his "savage wife" for his torments. The sinners ask for news of Florence, and Dante laments the current state of the city. At the top of the falls, at Virgil's order, Dante removes a cord from about his waist and Virgil drops it over the edge; as if in answer, a large, distorted shape swims up through the filthy air of the abyss.

Canto XVII

The creature is Geryon, the Monster of Fraud; Virgil announces that they must fly down from the cliff on the monster's back. Dante goes alone to examine the Usurers: he does not recognize them, but each has a heraldic device emblazoned on a leather purse around his neck ("On these their streaming eyes appeared to feast"[76]). The coats of arms indicate that they came from prominent Florentine families; they indicate the presence of Catello di Rosso Gianfigliazzi, Ciappo Ubriachi, the Paduan Reginaldo degli Scrovegni (who predicts that his fellow Paduan Vitaliano di Iacopo Vitaliani will join him here), and Giovanni di Buiamonte. Dante then rejoins Virgil and, both mounted atop Geryon's back, the two begin their descent from the great cliff in the Eighth Circle: the Hell of the Fraudulent and Malicious.

Geryon, the winged monster who allows Dante and Virgil to descend a vast cliff to reach the Eighth Circle, was traditionally represented as a giant with three heads and three conjoined bodies.[77] Dante's Geryon, meanwhile, is an image of fraud,[78] combining human, bestial, and reptilian elements: Geryon is a "monster with the general shape of a wyvern but with the tail of a scorpion, hairy arms, a gaudily-marked reptilian body, and the face of a just and honest man".[79] The pleasant human face on this grotesque body evokes the insincere fraudster whose intentions "behind the face" are all monstrous, cold-blooded, and stinging with poison.

Eighth Circle (Fraud)

Canto XVIII

Dante now finds himself in the Eighth Circle, called Malebolge ("Evil ditches"): the upper half of the Hell of the Fraudulent and Malicious. The Eighth Circle is a large funnel of stone shaped like an amphitheatre around which run a series of ten deep, narrow, concentric ditches or trenches called bolge (singular: bolgia). Within these ditches are punished those guilty of Simple Fraud. From the foot of the Great Cliff to the Well (which forms the neck of the funnel) are large spurs of rock, like umbrella ribs or spokes, which serve as bridges over the ten ditches. Dorothy L. Sayers writes that the Malebolge is "the image of the City in corruption: the progressive disintegration of every social relationship, personal and public. Sexuality, ecclesiastical and civil office, language, ownership, counsel, authority, psychic influence, and material interdependence – all the media of the community's interchange are perverted and falsified".[80]

- Bolgia 1 – Panderers and seducers: These sinners make two files, one along either bank of the ditch, and march quickly in opposite directions while being whipped by horned demons for eternity. They "deliberately exploited the passions of others and so drove them to serve their own interests, are themselves driven and scourged".[80] Dante makes reference to a recent traffic rule developed for the Jubilee year of 1300 in Rome.[80] In the group of panderers, the poets notice Venedico Caccianemico, a Bolognese Guelph who sold his own sister Ghisola to the Marchese d'Este. In the group of seducers, Virgil points out Jason, the Greek hero who led the Argonauts to fetch the Golden Fleece from Aeëtes, King of Colchis. He gained the help of the king's daughter, Medea, by seducing and marrying her only to later desert her for Creusa.[80] Jason had previously seduced Hypsipyle when the Argonauts landed at Lemnos on their way to Colchis, but "abandoned her, alone and pregnant".[81]

- Bolgia 2 – Flatterers: These also exploited other people, this time abusing and corrupting language to play upon others' desires and fears. They are steeped in excrement (representative of the false flatteries they told on earth) as they howl and fight amongst themselves. Alessio Interminei of Lucca and Thaïs are seen here.[80]

Canto XIX

- Bolgia 3 – Simoniacs: Dante now forcefully expresses his condemnation of those who committed simony, or the sale of ecclesiastic favors and offices, and therefore made money for themselves out of what belongs to God: "Rapacious ones, who take the things of God, / that ought to be the brides of Righteousness, / and make them fornicate for gold and silver! / The time has come to let the trumpet sound / for you; ...".[82] The sinners are placed head-downwards in round, tube-like holes within the rock (debased mockeries of baptismal fonts), with flames burning the soles of their feet. The heat of the fire is proportioned to their guilt. The simile of baptismal fonts gives Dante an incidental opportunity to clear his name of an accusation of malicious damage to the font at the Baptistery of San Giovanni.[83] Simon Magus, who offered gold in exchange for holy power to Saint Peter and after whom the sin is named, is mentioned here (although Dante does not encounter him). One of the sinners, Pope Nicholas III, must serve in the hellish baptism by fire from his death in 1280 until 1303 – the arrival in Hell of Pope Boniface VIII – who will take his predecessor's place in the stone tube until 1314, when he will in turn be replaced by Pope Clement V, a puppet of King Philip IV of France who moved the Papal See to Avignon, ushering in the Avignon Papacy (1309–77). Dante delivers a denunciation of simoniacal corruption of the Church.

Canto XX

Bolgia 4 – Sorcerers: In the middle of the bridge of the Fourth Bolgia, Dante looks down at the souls of fortune tellers, diviners, astrologers, and other false prophets. The punishment of those who attempted to "usurp God's prerogative by prying into the future",[84] is to have their heads twisted around on their bodies; in this horrible contortion of the human form, these sinners are compelled to walk backwards for eternity, blinded by their own tears. John Ciardi writes, "Thus, those who sought to penetrate the future cannot even see in front of themselves; they attempted to move themselves forward in time, so must they go backwards through all eternity; and as the arts of sorcery are a distortion of God's law, so are their bodies distorted in Hell."[85] While referring primarily to attempts to see into the future by forbidden means, this also symbolises the twisted nature of magic in general.[84] Dante weeps in pity, and Virgil rebukes him, saying, "Here pity only lives when it is dead; / for who can be more impious than he / who links God's judgment to passivity?"[86] Virgil gives a lengthy explanation of the founding of his native city of Mantua. Among the sinners in this circle are King Amphiaraus (one of the Seven against Thebes; foreseeing his death in the war, he sought to avert it by hiding from battle but died in an earthquake trying to flee) and two Theban soothsayers: Tiresias (in Ovid's Metamorphoses III, 324–331, Tiresias was transformed into a woman upon striking two coupling serpents with his rod; seven years later, he was changed back to a man in an identical encounter) and his daughter Manto. Also in this bolgia are Aruns (an Etruscan soothsayer who predicted the Caesar's victory in the Roman civil war in Lucan's Pharsalia I, 585–638), the Greek augur Eurypylus, astrologers Michael Scot (served at Frederick II's court at Palermo) and Guido Bonatti (served the court of Guido da Montefeltro), and Asdente (a shoemaker and soothsayer from Parma). Virgil implies that the moon is now setting over the Pillars of Hercules in the West: the time is just after 6:00 AM, the dawn of Holy Saturday.

Canto XXI

- Bolgia 5 – Barrators: Corrupt politicians, who made money by trafficking in public offices (the political analogue of the simoniacs), are immersed in a lake of boiling pitch, which represents the sticky fingers and dark secrets of their corrupt deals.[87] They are guarded by demons called the Malebranche ("Evil Claws"), who tear them to pieces with claws and grappling hooks if they catch them above the surface of the pitch. The Poets observe a demon arrive with a grafting Senator of Lucca and throw him into the pitch where the demons set upon him. Virgil secures safe-conduct from the leader of the Malebranche, named Malacoda ("Evil Tail"). He informs them that the bridge across the Sixth Bolgia is shattered (as a result of the earthquake that shook Hell at the death of Christ in 34 AD) but that there is another bridge further on. He sends a squad of demons led by Barbariccia to escort them safely. Based on details in this Canto (and if Christ's death is taken to have occurred at exactly noon), the time is now 7:00 AM of Holy Saturday.[88][nb 4] The demons provide some satirical black comedy – in the last line of Canto XXI, the sign for their march is provided by a fart: "and he had made a trumpet of his ass".[90]

Canto XXII

One of the grafters, an unidentified Navarrese (identified by early commentators as Ciampolo) is seized by the demons, and Virgil questions him. The sinner speaks of his fellow grafters, Friar Gomita (a corrupt friar in Gallura eventually hanged by Nino Visconti (see Purg. VIII) for accepting bribes to let prisoners escape) and Michel Zanche (a corrupt Vicar of Logodoro under King Enzo of Sardinia). He offers to lure some of his fellow sufferers into the hands of the demons, and when his plan is accepted he escapes back into the pitch. Alichino and Calcabrina start a brawl in mid-air and fall into the pitch themselves, and Barbariccia organizes a rescue party. Dante and Virgil take advantage of the confusion to slip away.

Canto XXIII

- Bolgia 6 – Hypocrites: The Poets escape the pursuing Malebranche by sliding down the sloping bank of the next pit. Here they find the hypocrites listlessly walking around a narrow track for eternity, weighted down by leaden robes. The robes are brilliantly gilded on the outside and are shaped like a monk's habit – the hypocrite's "outward appearance shines brightly and passes for holiness, but under that show lies the terrible weight of his deceit",[91] a falsity that weighs them down and makes spiritual progress impossible for them.[92] Dante speaks with Catalano dei Malavolti and Loderingo degli Andalò, two Bolognese brothers of the Jovial Friars, an order that had acquired a reputation for not living up to its vows and was eventually disbanded by Papal decree.[92] Friar Catalano points out Caiaphas, the High Priest of Israel under Pontius Pilate, who counseled the Pharisees to crucify Jesus for the public good (John 11:49–50). He himself is crucified to the floor of Hell by three large stakes, and in such a position that every passing sinner must walk upon him: he "must suffer upon his body the weight of all the world's hypocrisy".[91] The Jovial Friars explain to Virgil how he may climb from the pit; Virgil discovers that Malacoda lied to him about the bridges over the Sixth Bolgia.

Canto XXIV

- Bolgia 7 – Thieves: Dante and Virgil leave the bolgia of the Hypocrites by climbing the ruined rocks of a bridge destroyed by the great earthquake, after which they cross the bridge of the Seventh Bolgia to the far side to observe the next chasm. The pit is filled with monstrous reptiles: the shades of thieves are pursued and bitten by snakes and lizards, who curl themselves about the sinners and bind their hands behind their backs. The full horror of the thieves' punishment is revealed gradually: just as they stole other people's substance in life, their very identity becomes subject to theft here.[93] One sinner, who reluctantly identifies himself as Vanni Fucci, is bitten by a serpent at the jugular vein, bursts into flames, and is re-formed from the ashes like a phoenix. Vanni tells a dark prophecy against Dante.

Canto XXV

Vanni hurls an obscenity at God and the serpents swarm over him. The centaur Cacus arrives to punish him; he has a fire-breathing dragon on his shoulders and snakes covering his equine back. (In Roman mythology, Cacus, the monstrous, fire-breathing son of Vulcan, was killed by Hercules for raiding the hero's cattle; in Aeneid VIII, 193–267, Virgil did not describe him as a centaur). Dante then meets five noble thieves of Florence and observes their various transformations. Agnello Brunelleschi, in human form, is merged with the six-legged serpent that is Cianfa Donati. A figure named Buoso (perhaps either Buoso degli Abati or Buoso Donati, the latter of whom is mentioned in Inf. XXX.44) first appears as a man, but exchanges forms with Francesco de' Cavalcanti, who bites Buoso in the form of a four-footed serpent. Puccio Sciancato remains unchanged for the time being.

Canto XXVI

- Bolgia 8 – Counsellors of Fraud: Dante addresses a passionate lament to Florence before turning to the next bolgia. Here, fraudulent advisers or evil counsellors move about, hidden from view inside individual flames. These are not people who gave false advice, but people who used their position to advise others to engage in fraud. Ulysses and Diomedes are punished together within a great double-headed flame; they are condemned for the stratagem of the Trojan Horse (resulting in the Fall of Troy), for persuading Achilles to sail for Troy (causing Deidamia to die of grief), and for the theft of the sacred statue of Pallas, the Palladium (upon which, it was believed, the fate of Troy depended). Ulysses, the figure in the larger horn of the flame, narrates the tale of his last voyage and death, a creation of Dante's that illustrates the extent of his own pride despite his condemnation of this principal vice throughout the Divine Comedy.[94] Ulysses tells how, after his detainment by Circe, his love for neither his son, his father, nor his wife could overpower his desire to set out on the open sea to "gain experience of the world / and of the vices and the worth of men". As they approach the Pillars of Hercules, Ulysses urges his crew:

Consider well the seed that gave you birth:

you were not made to live your lives as brutes,

but to be followers of worth and knowledge.[95]

- This passage exemplifies the danger of utilizing rhetoric without proper wisdom, a failing condemned by several of Dante's most prominent philosophical influences.[94] Although Ulysses successfully convinces his crew to venture into the unknown, he lacks the wisdom to understand the danger this entails, leading to their death in a shipwreck after sighting Mount Purgatory in the Southern Hemisphere.

Canto XXVII

Dante is approached by Guido da Montefeltro, head of the Ghibellines of Romagna, asking for news of his country. Dante replies with a tragic summary of the current state of the cities of Romagna. Guido then recounts his life: he advised Pope Boniface VIII to offer a false amnesty to the Colonna family, who, in 1297, had walled themselves inside the castle of Palestrina in the Lateran. When the Colonna accepted the terms and left the castle, the Pope razed it to the ground and left them without a refuge. Guido describes how St. Francis, founder of the Franciscan order, came to take his soul to Heaven, only to have a devil assert prior claim. Although Boniface had absolved Guido in advance for his evil advice, the devil points out the invalidity: absolution requires contrition, and a man cannot be contrite for a sin at the same time that he is intending to commit it.[96]

Canto XXVIII

- Bolgia 9 – Sowers of Discord: In the Ninth Bolgia, the Sowers of Discord are hacked and mutilated for all eternity by a large demon wielding a bloody sword; their bodies are divided as, in life, their sin was to tear apart what God had intended to be united;[97] these are the sinners who are "ready to rip up the whole fabric of society to gratify a sectional egotism".[98] The souls must drag their ruined bodies around the ditch, their wounds healing in the course of the circuit, only to have the demon tear them apart anew. These are divided into three categories: (i) religious schism and discord, (ii) civil strife and political discord, and (iii) family disunion, or discord between kinsmen. Chief among the first category is Muhammad, the founder of Islam: his body is ripped from groin to chin, with his entrails hanging out. Dante apparently saw Muhammad as causing a schism within Christianity when he and his followers splintered off.[98][99] Dante also condemns Muhammad's son-in-law, Ali, for schism between Sunni and Shiite: his face is cleft from top to bottom. Muhammad tells Dante to warn the schismatic and heretic Fra Dolcino. In the second category are Pier da Medicina (his throat slit, nose slashed off as far as the eyebrows, a wound where one of his ears had been), the Roman tribune Gaius Scribonius Curio (who advised Caesar to cross the Rubicon and thus begin the Civil War; his tongue is cut off), and Mosca dei Lamberti (who incited the Amidei family to kill Buondelmonte dei Buondelmonti, resulting in conflict between Guelphs and Ghibellines; his arms are hacked off). Finally, in the third category of sinner, Dante sees Bertrand de Born (1140–1215). The knight carries around his severed head by its own hair, swinging it like a lantern. Bertrand is said to have caused a quarrel between Henry II of England and his son Prince Henry the Young King; his punishment in Hell is decapitation, since dividing father and son is like severing the head from the body.[98]

Canto XXIX

- Bolgia 10 – Falsifiers: The final bolgia of the Eighth Circle, is home to various sorts of falsifiers. A "disease" on society, they are themselves afflicted with different types of afflictions:[100] horrible diseases, stench, thirst, filth, darkness, and screaming. Some lie prostrate while others run hungering through the pit, tearing others to pieces. Shortly before their arrival in this pit, Virgil indicates that it is approximately noon of Holy Saturday, and he and Dante discuss one of Dante's kinsmen (Geri de Bello) among the Sowers of Discord in the previous ditch. The first category of falsifiers Dante encounters are the Alchemists (Falsifiers of Things). He speaks with two spirits viciously scrubbing and clawing at their leprous scabs: Griffolino d'Arezzo (an alchemist who extracted money from the foolish Alberto da Siena on the promise of teaching him to fly; Alberto's reputed father the Bishop of Siena had Griffolino burned at the stake) and Capocchio (burned at the stake at Siena in 1293 for practicing alchemy).

Canto XXX

Suddenly, two spirits – Gianni Schicchi de' Cavalcanti and Myrrha, both punished as Imposters (Falsifiers of Persons) – run rabid through the pit. Schicchi sinks his teeth into the neck of an alchemist, Capocchio, and drags him away like prey. Griffolino explains how Myrrha disguised herself to commit incest with her father King Cinyras, while Schicchi impersonated the dead Buoso Donati to dictate a will giving himself several profitable bequests. Dante then encounters Master Adam of Brescia, one of the Counterfeiters (Falsifiers of Money): for manufacturing Florentine florins of twenty-one (rather than twenty-four) carat gold, he was burned at the stake in 1281. He is punished by a loathsome dropsy-like disease, which gives him a bloated stomach, prevents him from moving, and an eternal, unbearable thirst. Master Adam points out two sinners of the fourth class, the Perjurers (Falsifiers of Words). These are Potiphar's wife (punished for her false accusation of Joseph, Gen. 39:7–19) and Sinon, the Achaean spy who lied to the Trojans to convince them to take the Trojan Horse into their city (Aeneid II, 57–194); Sinon is here rather than in Bolgia 8 because his advice was false as well as evil. Both suffer from a burning fever. Master Adam and Sinon exchange abuse, which Dante watches until he is rebuked by Virgil. As a result of his shame and repentance, Dante is forgiven by his guide. Sayers remarks that the descent through Malebolge "began with the sale of the sexual relationship, and went on to the sale of Church and State; now, the very money is itself corrupted, every affirmation has become perjury, and every identity a lie"[100] so that every aspect of social interaction has been progressively destroyed.

Central Well of Malebolge

.jpg.webp)

Canto XXXI

Dante and Virgil approach the Central Well, at the bottom of which lies the Ninth and final Circle of Hell. The classical and biblical Giants – who perhaps symbolize pride and other spiritual flaws lying behind acts of treachery[101] – stand perpetual guard inside the well-pit, their legs embedded in the banks of the Ninth Circle while their upper halves rise above the rim and can be visible from the Malebolge.[102] Dante initially mistakes them for great towers of a city. Among the Giants, Virgil identifies Nimrod (who tried to build the Tower of Babel; he shouts out the unintelligible Raphèl mai amècche zabì almi); Ephialtes (who with his brother Otus tried to storm Olympus during the Gigantomachy; he has his arms chained up) and Briareus (who Dante claimed had challenged the gods); and Tityos and Typhon, who insulted Jupiter. Also here is Antaeus, who did not join in the rebellion against the Olympian gods and therefore is not chained. At Virgil's persuasion, Antaeus takes the poets in his large palm and lowers them gently to the final level of Hell.

Ninth Circle (Treachery)

Canto XXXII

At the base of the well, Dante finds himself within a large frozen lake: Cocytus, the Ninth Circle of Hell. Trapped in the ice, each according to his guilt, are punished sinners guilty of treachery against those with whom they had special relationships. The lake of ice is divided into four concentric rings (or "rounds") of traitors corresponding, in order of seriousness, to betrayal of family ties, betrayal of community ties, betrayal of guests, and betrayal of lords. This is in contrast to the popular image of Hell as fiery; as Ciardi writes, "The treacheries of these souls were denials of love (which is God) and of all human warmth. Only the remorseless dead center of the ice will serve to express their natures. As they denied God's love, so are they furthest removed from the light and warmth of His Sun. As they denied all human ties, so are they bound only by the unyielding ice."[103] This final, deepest level of hell is reserved for traitors, betrayers and oathbreakers (its most famous inmate is Judas Iscariot).

- Round 1 – Caina: this round is named after Cain, who killed his own brother in the first act of murder (Gen. 4:8). This round houses the Traitors to their Kindred: they have their necks and heads out of the ice and are allowed to bow their heads, allowing some protection from the freezing wind. Here Dante sees the brothers Alessandro and Napoleone degli Alberti, who killed each other over their inheritance and their politics some time between 1282 and 1286. Camiscion de' Pazzi, a Ghibelline who murdered his kinsman Ubertino, identifies several other sinners: Mordred (traitorous son of King Arthur); Vanni de' Cancellieri, nicknamed Focaccia (a White Guelph of Pistoia who killed his cousin, Detto de' Cancellieri); and Sassol Mascheroni of the noble Toschi family of Florence (murdered a relative). Camiscion is aware that, in July 1302, his relative Carlino de' Pazzi would accept a bribe to surrender the Castle of Piantravigne to the Blacks, betraying the Whites. As a traitor to his party, Carlino belongs in Antenora, the next circle down – his greater sin will make Camiscion look virtuous by comparison.[102]

- Round 2 – Antenora: the second round is named after Antenor, a Trojan soldier who betrayed his city to the Greeks. Here lie the Traitors to their Country: those who committed treason against political entities (parties, cities, or countries) have their heads above the ice, but they cannot bend their necks. Dante accidentally kicks the head of Bocca degli Abati, a traitorous Guelph of Florence, and then proceeds to treat him more savagely than any other soul he has thus far met. Also punished in this level are Buoso da Duera (Ghibelline leader bribed by the French to betray Manfred, King of Naples), Tesauro dei Beccheria (a Ghibelline of Pavia; beheaded by the Florentine Guelphs for treason in 1258), Gianni de' Soldanieri (noble Florentine Ghibelline who joined with the Guelphs after Manfred's death in 1266), Ganelon (betrayed the rear guard of Charlemagne to the Muslims at Roncesvalles, according to the French epic poem The Song of Roland), and Tebaldello de' Zambrasi of Faenza (a Ghibelline who turned his city over to the Bolognese Guelphs on Nov. 13, 1280). The Poets then see two heads frozen in one hole, one gnawing the nape of the other's neck.

Canto XXXIII

The gnawing sinner tells his story: he is Count Ugolino, and the head he gnaws belongs to Archbishop Ruggieri. In "the most pathetic and dramatic passage of the Inferno",[104] Ugolino describes how he conspired with Ruggieri in 1288 to oust his nephew, Nino Visconti, and take control over the Guelphs of Pisa. However, as soon as Nino was gone, the Archbishop, sensing the Guelphs' weakened position, turned on Ugolino and imprisoned him with his sons and grandsons in the Torre dei Gualandi. In March 1289, the Archbishop condemned the prisoners to death by starvation in the tower.

- Round 3 – Ptolomaea: the third region of Cocytus is named after Ptolemy, who invited his father-in-law Simon Maccabaeus and his sons to a banquet and then killed them (1 Maccabees 16).[105] Traitors to their Guests lie supine in the ice while their tears freeze in their eye sockets, sealing them with small visors of crystal – even the comfort of weeping is denied to them. Dante encounters Fra Alberigo, one of the Jovial Friars and a native of Faenza, who asks Dante to remove the visor of ice from his eyes. In 1285, Alberigo invited his opponents, Manfred (his brother) and Alberghetto (Manfred's son), to a banquet at which his men murdered the dinner guests. He explains that often a living person's soul falls to Ptolomea before he dies ("before dark Atropos has cut their thread"[106]). Then, on earth, a demon inhabits the body until the body's natural death. Fra Alberigo's sin is identical in kind to that of Branca d'Oria, a Genoese Ghibelline who, in 1275, invited his father-in-law, Michel Zanche (seen in the Eighth Circle, Bolgia 5) and had him cut to pieces. Branca (that is, his earthly body) did not die until 1325, but his soul, together with that of his nephew who assisted in his treachery, fell to Ptolomaea before Michel Zanche's soul arrived at the bolgia of the Barrators. Dante leaves without keeping his promise to clear Fra Alberigo's eyes of ice ("And yet I did not open them for him; / and it was courtesy to show him rudeness"[107]).

Canto XXXIV

- Round 4 – Judecca: the fourth division of Cocytus, named for Judas Iscariot, contains the Traitors to their Lords and benefactors. Upon entry into this round, Virgil says "Vexilla regis prodeunt inferni" ("The banners of the King of Hell draw closer").[108] Judecca is completely silent: all of the sinners are fully encapsulated in ice, distorted and twisted in every conceivable position. The sinners present an image of utter immobility: it is impossible to talk with any of them, so Dante and Virgil quickly move on to the centre of Hell.

Centre of Hell

In the very centre of Hell, condemned for committing the ultimate sin (personal treachery against God), is the Devil, referred to by Virgil as Dis (the Roman god of the underworld; the name "Dis" was often used for Pluto in antiquity, such as in Virgil's Aeneid). The arch-traitor, Lucifer was once held by God to be fairest of the angels before his pride led him to rebel against God, resulting in his expulsion from Heaven. Lucifer is a giant, terrifying beast trapped waist-deep in the ice, fixed and suffering. He has three faces, each a different color: one red (the middle), one a pale yellow (the right), and one black (the left):

... he had three faces: one in front bloodred;

and then another two that, just above

the midpoint of each shoulder, joined the first;

and at the crown, all three were reattached;

the right looked somewhat yellow, somewhat white;

the left in its appearance was like those

who come from where the Nile, descending, flows.[109]

Dorothy L. Sayers notes that Satan's three faces are thought by some to suggest his control over the three human races: red for the Europeans (from Japheth), yellow for the Asiatic (from Shem), and black for the African (the race of Ham).[110] All interpretations recognize that the three faces represent a fundamental perversion of the Trinity: Satan is impotent, ignorant, and full of hate, in contrast to the all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-loving nature of God.[110] Lucifer retains his six wings (he originally belonged to the angelic order of Seraphim, described in Isaiah 6:2), but these are now dark, bat-like, and futile: the icy wind that emanates from the beating of Lucifer's wings only further ensures his own imprisonment in the frozen lake. He weeps from his six eyes, and his tears mix with bloody froth and pus as they pour down his three chins. Each face has a mouth that chews eternally on a prominent traitor. Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus dangle with their feet in the left and right mouths, respectively, for their involvement in the assassination of Julius Caesar (March 15, 44 BC) – an act which, to Dante, represented the destruction of a unified Italy and the killing of the man who was divinely appointed to govern the world.[110] In the central, most vicious mouth is Judas Iscariot, the apostle who betrayed Christ. Judas is receiving the most horrifying torture of the three traitors: his head is gnawed inside Lucifer's mouth while his back is forever flayed and shredded by Lucifer's claws. According to Dorothy L. Sayers, "just as Judas figures treason against God, so Brutus and Cassius figure treason against Man-in-Society; or we may say that we have here the images of treason against the Divine and the Secular government of the world".[110]

At about 6:00 p.m. on Saturday evening, Virgil and Dante begin their escape from Hell by clambering down Satan's ragged fur, feet-first. When they reach Satan's genitalia, the poets pass through the center of the universe and of gravity from the Northern Hemisphere of land to the Southern Hemisphere of water. When Virgil changes direction and begins to climb "upward" towards the surface of the Earth at the antipodes, Dante, in his confusion, initially believes they are returning to Hell. Virgil indicates that the time is halfway between the canonical hours of Prime (6:00 a.m.) and Terce (9:00 a.m.) — that is, 7:30 a.m. of the same Holy Saturday which was just about to end. Dante is confused as to how, after about an hour and a half of climbing, it is now apparently morning. Virgil explains that it is as a result of passing through the Earth's center into the Southern Hemisphere, which is twelve hours ahead of Jerusalem, the central city of the Northern Hemisphere (where, therefore, it is currently 7:30 p.m.).

Virgil goes on to explain how the Southern Hemisphere was once covered with dry land, but the land recoiled in horror to the north when Lucifer fell from Heaven and was replaced by the ocean. Meanwhile, the inner rock Lucifer displaced as he plunged into the center of the earth rushed upwards to the surface of the Southern Hemisphere to avoid contact with him, forming the Mountain of Purgatory. This mountain — the only land mass in the waters of the Southern Hemisphere — rises above the surface at a point directly opposite Jerusalem. The poets then ascend a narrow chasm of rock through the "space contained between the floor formed by the convex side of Cocytus and the underside of the earth above,"[111] moving in opposition to Lethe, the river of oblivion, which flows down from the summit of Mount Purgatory. The poets finally emerge a little before dawn on the morning of Easter Sunday (April 10, 1300) beneath a sky studded with stars.

Illustrations

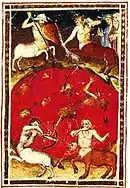

Dialogo di Antonio Manetti cittadino fiorentino circa al sito, forma, et misure dello inferno di Dante Alighieri poeta excellentissimo [Florence: F. Giunta, 1510?].

Everything Reduced to One Plan, 1506

Everything Reduced to One Plan, 1506 The Chamber of Hell, 1506

The Chamber of Hell, 1506 Overview of Hell, 1506

Overview of Hell, 1506 Circles Six and Seven, 1506

Circles Six and Seven, 1506 The Lair of Geryon, 1506

The Lair of Geryon, 1506 The Tomb of Lucifer, 1506

The Tomb of Lucifer, 1506

See also

- Allegory in the Middle Ages

- Dante Alighieri and the Divine Comedy in popular culture

- Great refusal

- List of cultural references in the Divine Comedy

Notes

- There are many English translations of this famous line. Some examples include

- All hope abandon, ye who enter here – Henry Francis Cary (1805–1814)

- All hope abandon, ye who enter in! – Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1882)

- Leave every hope, ye who enter! – Charles Eliot Norton (1891)

- Leave all hope, ye that enter – Carlyle-Okey-Wicksteed (1932)

- Lay down all hope, you that go in by me. – Dorothy L. Sayers (1949)

- Abandon all hope, ye who enter here – John Ciardi (1954)

- Abandon every hope, you who enter. – Charles S. Singleton (1970)

- No room for hope, when you enter this place – C. H. Sisson (1980)

- Abandon every hope, who enter here. – Allen Mandelbaum (1982)

- Abandon all hope, you who enter here. – Robert Pinsky (1993); Robert Hollander (2000)

- Abandon every hope, all you who enter – Mark Musa (1995)

- Abandon every hope, you who enter. – Robert M. Durling (1996)

- Mandelbaum, note to his translation, p. 357 of the Bantam Dell edition, 2004, says that Dante may simply be preserving an ancient conflation of the two deities; Peter Bondanella in his note to the translation of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Inferno: Dante Alighieri (Barnes & Noble Classics, 2003), pp. 202–203, thinks Plutus is meant, since Pluto is usually identified with Dis, and Dis is a distinct figure.

- The punishment of immersion was not typically ascribed in Dante's age to the violent, but the Visio attaches it to those who facere praelia et homicidia et rapinas pro cupiditate terrena ("make battle and murder and rapine because of worldly cupidity"). Theodore Silverstein (1936), "Inferno, XII, 100–126, and the Visio Karoli Crassi," Modern Language Notes, 51:7, 449–452, and Theodore Silverstein (1939), "The Throne of the Emperor Henry in Dante's Paradise and the Mediaeval Conception of Christian Kingship," Harvard Theological Review, 32:2, 115–129, suggests that Dante's interest in contemporary politics would have attracted him to a piece like the Visio. Its popularity assures that Dante would have had access to it. Jacques Le Goff, Goldhammer, Arthur, tr. (1986), The Birth of Purgatory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-47083-0), states definitively that ("we know [that]") Dante read it.

- Allen Mandelbaum on Canto XXI, lines 112–114: "the bridges of Hell crumbled 1266 years ago – at a time five hours later than the present hour yesterday. Dante held that Christ died after having completed 34 years of life on this earth – years counted from the day of the Incarnation. Luke affirms that the hour of His death was the sixth – that is, noon. If this is the case, then Malacoda is referring to a time which is 7 AM, five hours before noon on Holy Saturday."[89]

References

- John Ciardi, The Divine Comedy, Introduction by Archibald T. MacAllister, p. 14

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes, p. 19.

- Hollander, Robert (2000). Note on Inferno I.11. In Robert and Jean Hollander, trans., The Inferno by Dante. New York: Random House. p. 14. ISBN 0-385-49698-2

- Allen Mandelbaum, Inferno, notes on Canto I, p. 345

- Inf. Canto I, line 1

- Inf. Canto I, line 2

- Inf. Canto I, line 3

- Inf. Canto I, line 32

- Allaire, Gloria (7 August 1997). "New evidence towards identifying Dante's enigmatic lonza". Electronic Bulletin of the Dante Society of America.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) – defines lonza as the result of an unnatural pairing between a leopard and a lioness in Andrea da Barberino Guerrino meschino. - Inf. Canto I, line 45

- Inf. Canto I, line 49

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto I, p. 21

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto I.

- Inf. Canto I, line 61

- Inf. Canto I, line 60

- Inf. Canto I, line 70

- Inf. Canto III, line 9

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto III, p. 36

- Dorothly L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto III

- Inferno, Canto III, lines 95–96, Longfellow translation

- Brand, Peter; Pertile, Lino (1999). The Cambridge History of Italian Literature (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-521-66622-0.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XI, p. 94

- D. Sayers, Hell (Penguin 1975) p. 314 and p. 139

- D. Sayers, Hell (Penguin 1975) p. 136 (XI.80-82)

- D. Sayers, Hell (Penguin 1975) p. 139

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XI, p. 139

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto IV

- Inferno, Canto IV, line 36, Mandelbaum translation.

- Inferno, Canto IV, line 103, Ciardi translation.

- Inferno, Canto IV, line 123, Mandelbaum translation.

- Purgatorio, Canto XXII, lines 97–114

- in parte ove non è che luca (Inferno, Canto IV, line 151, Mandelbaum translation.)

- Senior, Matthew (1994). In the Grip of Minos: Confessional Discourse in Dante, Corneille, and Racine. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. p. 52. OCLC 625327952.

- Senior, Matthew (1994). In the Grip of Minos: Confessional Discourse in Dante, Corneille, and Racine. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. pp. 48–49. OCLC 625327952.

- i peccator carnali (Inferno, Canto V, line 38, Longfellow translation.)

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto V, p. 101–102

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto V, p. 51

- la ruina (Inferno, Canto V, line 34, Mandelbaum translation.)

- John Yueh-Han Yieh, One Teacher: Jesus' Teaching Role in Matthew's Gospel Report (Walter de Gruyter, 2005) p. 65; Robert Walter Funk, The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus (Harper San Francisco, 1998) pp. 129–270.

- Lansing, Richard. The Dante Encyclopedia. pp. 577–578.

- Inferno, Canto V, lines 100–108, Ciardi translation.

- Inferno Canto V, line 137

- Inferno, line 137, Ciardi translation.

- John Keats, On a Dream Archived 2009-10-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- Inferno, Canto V, lines 141–142, Mandelbaum translation.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, Canto VI, p. 54

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto VI.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, Introduction, p. xi.

- Wallace Fowlie, A Reading of Dante's Inferno, University of Chicago Press, 1981, pp. 51–52.

- "Giovanni Boccaccio, The Decameron, Ninth Day, Novel VIII". Stg.brown.edu. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- Inferno, Canto VII, line 47, Mandelbaum translation.

- Inferno, Canto VII, lines 25–30, Ciardi translation.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto VII, p. 114

- Inferno, Canto VII, lines 79–80, Mandelbaum translation.

- Inferno, Canto VII, lines 54, Mandelbaum translation.

- Dante, Alighieri; Durling, Robert M.; Martinez, Ronald L. (1997). The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195087444.

- Inferno, Canto VIII, lines 37–38, Mandelbaum translation.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto VIII.

- Allen Mandelbaum, Inferno, notes on Canto VIII, p. 358

- Inferno, Canto X, line 15, Mandelbaum translation.

- Inferno, Canto X, lines 103–108, Mandelbaum translation.

- Richard P. McBrien (1997). Lives of the Popes: The Pontiffs from St. Peter to John Paul II. HarperCollins. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-06-065304-0. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Alighieri, Dante (1995). Dante's Inferno. Translated by Mark Musa. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20930-6. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Hudson-Williams, T. (1951). "Dante and the Classics". Greece & Rome. 20 (58): 38–42. doi:10.1017/s0017383500011128. JSTOR 641391. S2CID 162510309.

Dante is not free from error in his allocation of sinners; he consigned Pope Anastasius II to the burning cauldrons of the Heretics because he mistook him for the emperor of the same name

- Zimmerman, Seth (2003). The Inferno of Dante Alighieri. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4697-2448-5. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XI.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XI, p. 95

- Inferno, Canto XII, lines 101–103, Longfellow translation

- John Ciardi, Inferno, Canto XII, p. 96

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XIII.

- Wallace Fowlie, A Reading of Dante's Inferno, University of Chicago Press, 1981, p. 224.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, Canto XIV, p. 112

- John Ciardi, Inferno, Canto XV, p. 119

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XV.

- Inferno, Canto XV, lines 85–87, Mandelbaum translation.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, Canto XVII, line 56

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XVII.

- Wallace Fowlie, A Reading of Dante's Inferno, University of Chicago Press, 1981, p. 117

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XVII, p. 138

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XVIII.

- Inferno, Canto XVIII, line 94, Mandelbaum translation.

- Inferno, Canto XIX, lines 2–6, Mandelbaum translation

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XIX.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XX.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XX, p. 157

- Inferno, Canto XX, lines 28–30, Mandelbaum translation.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXI.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XXI, p. 171

- Allen Mandelbaum, Inferno, notes on Canto XXI

- Patterson, Victoria (2011-11-15). "Great Farts in Literature". The Nervous Breakdown. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XXIII, p. 180

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXIII

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXIV.

- Mazzotta, Giuseppe (1999). "Canto XXVI, Ulysses: Persuasion versus Prophecy". In Mandelbaum, Allen; Oldcorn, Anthony; Ross, Charles (eds.). Lectura Dantis: Inferno. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 348–356. ISBN 978-0-520-21249-7.

- Inferno, Canto XXVI, lines 118–120, Mandelbaum translation.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXVII.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XXVIII, p. 217

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXVIII.

- Wallace Fowlie, A Reading of Dante's Inferno, University of Chicago Press, 1981, p. 178.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXIX.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXXI.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXXII.

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XXXII, p. 248

- John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XXXIII, p. 256

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXXIII.

- Inferno, Canto XXXIII, line 125, Ciardi translation

- Inferno, Canto XXXIII, lines 149–150, Mandelbaum translation.

- Inferno, Canto XXXIV, line 1, Mandelbaum translation

- Inferno, Canto XXXIV, lines 39–45, Mandelbaum translation.

- Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XXXIV.

- Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander, The Inferno, notes on Canto XXXIV, p. 641.

External links

Texts

- Dante Dartmouth Project: Full text of more than 70 Italian, Latin, and English commentaries on the Commedia, ranging in date from 1322 (Iacopo Alighieri) to the 2000s (Robert Hollander)

- World of Dante Multimedia website that offers Italian text of Divine Comedy, Allen Mandelbaum's translation, gallery, interactive maps, timeline, musical recordings, and searchable database for students and teachers by Deborah Parker and IATH (Institute for Advanced Technologies in the Humanities) of the University of Virginia

- Dante's Divine Comedy: Full text paraphrased in modern English verse by Scottish author and artist Alasdair Gray

- Audiobooks: Public domain recordings from LibriVox (in Italian, Longfellow translation); some additional recordings

Secondary materials

- A 72-piece art collection featured in Dante's Hell Animated and Inferno by Dante films.

- On-line Concordance to the Divine Comedy

- Wikisummaries summary and analysis of Inferno

- Danteworlds, multimedia presentation of the Divine Comedy for students by Guy Raffa of the University of Texas

- Dante's Places: a map (still a prototype) of the places named by Dante in the Commedia, created with GoogleMaps. Explanatory PDF is available for download

- See more Dante's Inferno images by selecting the ""Heaven & Hell" subject at the Persuasive Cartography, The PJ Mode Collection, Cornell University Library

- "Mapping Dante's Inferno, One Circle of Hell at a Time", article by Anika Burgess, Atlas Obscura, July 13, 2017

- Dante's Inferno on In Our Time at the BBC