Hecate

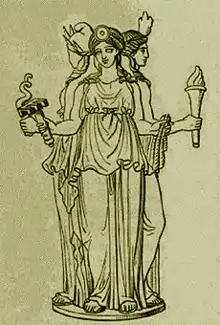

Hecate or Hekate[lower-alpha 1] is a goddess in ancient Greek religion and mythology, most often shown holding a pair of torches, a key, snakes, or accompanied by dogs,[1] and in later periods depicted as three-formed or triple-bodied. She is variously associated with crossroads, entrance-ways, night, light, magic, witchcraft, the Moon, knowledge of herbs and poisonous plants, graves, ghosts, necromancy, and sorcery.[2][3][4] Her earliest appearance in literature was in Hesiod's Theogony in the 8th century BCE[5] as a goddess of great honour with domains in sky, earth, and sea. Her place of origin is debated by scholars, but she had popular followings amongst the witches of Thessaly[6] and an important sanctuary among the Carian Greeks of Asia Minor in Lagina.[6]

| Hecate | |

|---|---|

Goddess of boundaries, crossroads, witchcraft, the Moon, necromancy, and ghosts | |

The Hecate Chiaramonti, a Roman sculpture of triple-bodied Hecate, after a Hellenistic original (Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums) | |

| Abode | Underworld |

| Animals | Dog, polecat |

| Symbol | Paired torches, dogs, serpents, keys, daggers, and Hecate's wheel is known as a stropholos. |

| Parents | Perses and Asteria |

| Offspring | Aegialeus, Circe, Empusa, Medea, Scylla |

| Equivalents | |

| Mesopotamian equivalent | Ereshkigal |

| Slavic equivalent | Marzanna |

| Roman equivalent | Trivia, Diana |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

|

| Greek deities series |

|---|

|

| Primordial deities |

| Chthonic deities |

Hecate was one of several deities worshipped in ancient Athens as a protector of the oikos (household), alongside Zeus, Hestia, Hermes, and Apollo.[7] In the post-Christian writings of the Chaldean Oracles (2nd–3rd century CE) she was also regarded with (some) rulership over earth, sea, and sky, as well as a more universal role as Savior (Soteira), Mother of Angels and the Cosmic World Soul.[8][9] Regarding the nature of her cult, it has been remarked, "she is more at home on the fringes than in the centre of Greek polytheism. Intrinsically ambivalent and polymorphous, she straddles conventional boundaries and eludes definition."[10]

The Romans knew her by the epithet of Trivia, an epithet she shares with Diana/Artemis, each in their roles as protector of travel and of the crossroads (trivia, "three ways").[11]

Name and origin

The origin of the name Hecate (Ἑκάτη, Hekátē) and the original country of her worship are both unknown, though several theories have been proposed.

Greek origin

Whether or not Hecate's worship originated in Greece, some scholars have suggested that the name derives from a Greek root, and several potential source words have been identified. For example, ἑκών "willing" (thus, "she who works her will" or similar), may be related to the name Hecate.[12] However, no sources suggested list will or willingness as a major attribute of Hecate, which makes this possibility unlikely.[13] Another Greek word suggested as the origin of the name Hecate is Ἑκατός Hekatos, an obscure epithet of Apollo[10] interpreted as "the far reaching one" or "the far-darter".[14] This has been suggested in comparison with the attributes of the goddess Artemis, strongly associated with Apollo and frequently equated with Hecate in the classical world. Supporters of this etymology suggest that Hecate was originally considered an aspect of Artemis prior to the latter's adoption into the Olympian pantheon. Artemis would have, at that point, become more strongly associated with purity and maidenhood, on the one hand, while her originally darker attributes like her association with magic, the souls of the dead, and the night would have continued to be worshipped separately under her title Hecate.[15] Though often considered the most likely Greek origin of the name, the Ἑκατός theory does not account for her worship in Asia Minor, where her association with Artemis seems to have been a late development, and the competing theories that the attribution of darker aspects and magic to Hecate were themselves not originally part of her cult.[13]

R. S. P. Beekes rejected a Greek etymology and suggested a Pre-Greek origin.[16]

Egyptian origin

A strong possibility for the foreign origin of the name may be Heqet (ḥqt), a frog-headed Egyptian goddess of fertility and childbirth, who, like Hecate, was also associated with ḥqꜣ, ruler.[17] The word "heka" in the Egyptian language is also both the word for "magic" and the name of the god of magic and medicine, Heka.[18]

Anatolian origin

Hecate possibly originated among the Carians of Anatolia,[6] the region where most theophoric names invoking Hecate, such as Hecataeus or Hecatomnus, the father of Mausolus, are attested,[19] and where Hecate remained a Great Goddess into historical times, at her unrivalled[lower-alpha 2] cult site in Lagina. While many researchers favour the idea that she has Anatolian origins, it has been argued that "Hecate must have been a Greek goddess."[lower-alpha 3] The monuments to Hecate in Phrygia and Caria are numerous but of late date.[21]

William Berg observes, "Since children are not called after spooks, it is safe to assume that Carian theophoric names involving hekat- refer to a major deity free from the dark and unsavoury ties to the underworld and to witchcraft associated with the Hecate of classical Athens."[22] In particular, there is some evidence that she might be derived from the local sun goddesses (see also Arinna) based on similar attributes.[23]

If Hecate's cult spread from Anatolia into Greece, then it possibly presented a conflict, as her role was already filled by other more prominent deities in the Greek pantheon, above all by Artemis and Selene. This line of reasoning lies behind the widely accepted hypothesis that she was a foreign deity who was incorporated into the Greek pantheon. Other than in the Theogony, the Greek sources do not offer a consistent story of her parentage or of her relations in the Greek pantheon.

Older English pronunciation

In Early Modern English, the name was also pronounced disyllabically (as /ˈhɛk.ɪt/) and sometimes spelled Hecat. It remained common practice in English to pronounce her name in two syllables, even when spelled with final e, well into the 19th century.

The spelling Hecat is due to Arthur Golding's 1567 translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses,[24] and this spelling without the final E later appears in plays of the Elizabethan-Jacobean period.[25] Webster's Dictionary of 1866 particularly credits the influence of Shakespeare for the then-predominant disyllabic pronunciation of the name.[26]

Iconography

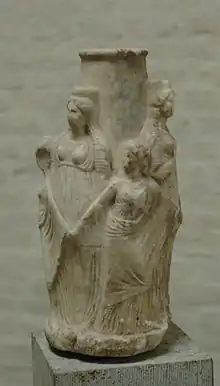

Hecate was generally represented as three-formed or triple-bodied, though the earliest known images of the goddess are singular. Her earliest known representation is a small terracotta statue found in Athens. An inscription on the statue is a dedication to Hecate, in writing of the style of the 6th century, but it otherwise lacks any other symbols typically associated with the goddess. She is seated on a throne, with a chaplet around her head; the depiction is otherwise relatively generic.[27] Farnell states: "The evidence of the monuments as to the character and significance of Hecate is almost as full as that of to express her manifold and mystic nature."[27] A 6th century fragment of pottery from Boetia depicts a goddess which may be Hecate in a maternal or fertility mode. Crowned with leafy branches as in later descriptions, she is depicted offering a "maternal blessing" to two maidens who embrace her. The figure is flanked by lions, an animal associated with Hecate both in the Chaldean Oracles, coinage, and reliefs from Asia Minor.[28] In artwork, she is often portrayed in three statues standing back to back, each with its own special attributes (torch, keys, daggers, snakes, dogs).[3]

The 2nd-century travel writer Pausanias stated that Hecate was first depicted in triplicate by the sculptor Alcamenes in the Greek Classical period of the late 5th century BC,[4] whose sculpture was placed before the temple of the Wingless Nike in Athens. Though Alcamenes' original statue is lost, hundreds of copies exist, and the general motif of a triple Hecate situated around a central pole or column, known as a hekataion, was used both at crossroads shrines as well as at the entrances to temples and private homes. These typically depict her holding a variety of items, including torches, keys, serpents, and daggers.[29][28] Some hekataia, including a votive sculpture from Attica of the 3rd century BC, include additional dancing figures identified as the Charites circling the triple Hecate and her central column. It is possible that the representation of a triple Hecate surrounding a central pillar was originally derived from poles set up at three-way crossroads with masks hung on them, facing in each road direction. In the 1st century AD, Ovid wrote: "Look at Hecate, standing guard at the crossroads, one face looking in each direction."[28]

Apart from traditional hekataia, Hecate's triplicity is depicted in the vast frieze of the great Pergamon Altar, now in Berlin, wherein she is shown with three bodies, taking part in the battle with the Titans. In the Argolid, near the shrine of the Dioscuri, Pausanias saw the temple of Hecate opposite the sanctuary of Eileithyia; He reported the image to be the work of Scopas, stating further, "This one is of stone, while the bronze images opposite, also of Hecate, were made respectively by Polycleitus and his brother Naucydes, son of Mothon."[30]

While Greek anthropomorphic conventions of art generally represented Hecate's triple form as three separate bodies, the iconography of the triple Hecate eventually evolved into representations of the goddess with a single body, but three faces. In Egyptian-inspired Greek esoteric writings connected with Hermes Trismegistus, and in the Greek Magical Papyri of Late Antiquity, Hecate is described as having three heads: one dog, one serpent, and one horse. In other representations, her animal heads include those of a cow and a boar.[31]

The east frieze of a Hellenistic temple of hers at Lagina shows her helping protect the newborn Zeus from his father Cronus; this frieze is the only evidence of Hecate's involvement in the myth of his birth.[32][33]

Sacred animals

Dogs were closely associated with Hecate in the Classical world. "In art and in literature Hecate is constantly represented as dog-shaped or as accompanied by a dog. Her approach was heralded by the howling of a dog. The dog was Hecate's regular sacrificial animal, and was often eaten in solemn sacrament."[34] The sacrifice of dogs to Hecate is attested for Thrace, Samothrace, Colophon, and Athens.[10] A 4th century BCE marble relief from Crannon in Thessaly was dedicated by a race-horse owner.[lower-alpha 4] It shows Hecate, with a hound beside her, placing a wreath on the head of a mare. It has been claimed that her association with dogs is "suggestive of her connection with birth, for the dog was sacred to Eileithyia, Genetyllis, and other birth goddesses. Images of her attended by a dog[35] are also found at times when she is shown as in her role as mother goddess with child, and when she is depicted alongside the god Hermes and the goddess Cybele in reliefs.[36]

Although in later times Hecate's dog came to be thought of as a manifestation of restless souls or daemons who accompanied her, its docile appearance and its accompaniment of a Hecate who looks completely friendly in many pieces of ancient art suggests that its original signification was positive and thus likelier to have arisen from the dog's connection with birth than the dog's underworld associations."[37] The association with dogs, particularly female dogs, could be explained by a metamorphosis myth in Lycophron: the friendly looking female dog accompanying Hecate was originally the Trojan Queen Hecuba, who leapt into the sea after the fall of Troy and was transformed by Hecate into her familiar.[38]

The polecat is also associated with Hecate. Antoninus Liberalis used a myth to explain this association:

- "At Thebes Proetus had a daughter Galinthias. This maiden was playmate and companion of Alcmene, daughter of Electryon. As the birth throes for Herakles were pressing on Alcmene, the Moirai (fates) and Eileithyia (birth-goddess), as a favour to Hera, kept Alcmene in continuous birth pangs. They remained seated, each keeping their arms crossed. Galinthias, fearing that the pains of her labour would drive Alcmene mad, ran to the Moirai and Eileithyia and announced that by desire of Zeus a boy had been born to Alcmene and that their prerogatives had been abolished. At all this, consternation of course overcame the Moirai and they immediately let go their arms.

- Alcmene’s pangs ceased at once and Herakles was born. The Moirai were aggrieved at this and took away the womanly parts of Galinthias since, being but a mortal, she had deceived the gods. They turned her into a deceitful weasel (or polecat), making her live in crannies and gave her a grotesque way of mating. She is mounted through the ears and gives birth by bringing forth her young through the throat. Hecate felt sorry for this transformation of her appearance and appointed her a sacred servant of herself."[39]

Aelian told a different story of a woman transformed into a polecat:

- "I have heard that the polecat was once a human being. It has also reached my hearing that Gale was her name then; that she was a dealer in spells and a sorceress (pharmakis); that she was extremely incontinent, and that she was afflicted with abnormal sexual desires. Nor has it escaped my notice that the anger of the goddess Hekate transformed it into this evil creature. May the goddess be gracious to me: Fables and their telling I leave to others."[40]

Athenaeus of Naucratis, drawing on the etymological speculation of Apollodorus of Athens, notes that the red mullet is sacred to Hecate, "on account of the resemblance of their names; for that the goddess is trimorphos, of a triple form". The Greek word for mullet was trigle and later trigla. He goes on to quote a fragment of verse:

- "O mistress Hecate, Trioditis

- With three forms and three faces

- Propitiated with mullets".[41]

In relation to Greek concepts of pollution, Parker observes,

- "The fish that was most commonly banned was the red mullet (trigle), which fits neatly into the pattern. It 'delighted in polluted things', and 'would eat the corpse of a fish or a man'. Blood-coloured itself, it was sacred to the blood-eating goddess Hecate. It seems a symbolic summation of all the negative characteristics of the creatures of the deep."[42]

At Athens, it is said there stood a statue of Hecate Triglathena, to whom the red mullet was offered in sacrifice.[43] After mentioning that this fish was sacred to Hecate, Alan Davidson writes,

- "Cicero, Horace, Juvenal, Martial, Pliny, Seneca, and Suetonius have left abundant and interesting testimony to the red mullet fever which began to affect wealthy Romans during the last years of the Republic and really gripped them in the early Empire. The main symptoms were a preoccupation with size, the consequent rise to absurd heights of the prices of large specimens, a habit of keeping red mullet in captivity, and the enjoyment of the highly specialized aesthetic experience induced by watching the color of the dying fish change."[44]

In her three-headed representations, discussed above, Hecate often has one or more animal heads, including cow, dog, boar, serpent, and horse.[45] Lions are associated with Hecate in early artwork from Asia Minor, as well as later coins and literature, including the Chaldean Oracles.[28] The frog, which was also the symbol of the similarly named Egyptian goddess Heqet,[46] has also become sacred to Hecate in modern pagan literature, possibly due in part to its ability to cross between two elements.[47]

Comparative mythologist Alexander Haggerty Krappe cited that Hecate was also named ίππεύτρια (hippeutria – 'the equestrienne'), since the horse was "the chthonic animal par excellence".[48]

Sacred plants

Hecate was closely associated with plant lore and the concoction of medicines and poisons. In particular she was thought to give instruction in these closely related arts. Apollonius of Rhodes, in the Argonautica mentions that Medea was taught by Hecate, "I have mentioned to you before a certain young girl whom Hecate, daughter of Perses, has taught to work in drugs."[49]

The goddess is described as wearing oak in fragments of Sophocles' lost play The Root Diggers (or The Root Cutters), and an ancient commentary on Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica (3.1214) describes her as having a head surrounded by serpents, twining through branches of oak.[50]

The yew in particular was sacred to Hecate.

Greeks held the yew to be sacred to Hecate... Her attendants draped wreathes of yew around the necks of black bulls which they slaughtered in her honor and yew boughs were burned on funeral pyres. The yew was associated with the alphabet and the scientific name for yew today, taxus, was probably derived from the Greek word for yew, toxos, which is hauntingly similar to toxon, their word for bow and toxicon, their word for poison. It is presumed that the latter were named after the tree because of its superiority for both bows and poison.[51]

Hecate was said to favour offerings of garlic, which was closely associated with her cult.[52] She is also sometimes associated with cypress, a tree symbolic of death and the underworld, and hence sacred to a number of chthonic deities.[53]

A number of other plants (often poisonous, medicinal and/or psychoactive) are associated with Hecate.[54] These include aconite (also called hecateis),[55] belladonna, dittany, and mandrake. It has been suggested that the use of dogs for digging up mandrake is further corroboration of the association of this plant with Hecate; indeed, since at least as early as the 1st century CE, there are a number of attestations to the apparently widespread practice of using dogs to dig up plants associated with magic.[56]

Functions

As a goddess of boundaries

Hecate was associated with borders, city walls, doorways, crossroads and, by extension, with realms outside or beyond the world of the living. She appears to have been particularly associated with being 'between' and hence is frequently characterized as a "liminal" goddess. "Hecate mediated between regimes—Olympian and Titan—but also between mortal and divine spheres."[57] This liminal role is reflected in a number of her cult titles: Apotropaia (that turns away/protects); Enodia (on the way); Propulaia/Propylaia (before the gate); Triodia/Trioditis (who frequents crossroads); Klêidouchos (holding the keys), etc.

As a goddess expected to avert harmful or destructive spirits from the house or city over which she stood guard and to protect the individual as she or he passed through dangerous liminal places, Hecate would naturally become known as a goddess who could also refuse to avert the demons, or even drive them on against unfortunate individuals.[58]

It was probably her role as guardian of entrances that led to Hecate's identification by the mid fifth century with Enodia, a Thessalian goddess. Enodia's very name ("In-the-Road") suggests that she watched over entrances, for it expresses both the possibility that she stood on the main road into a city, keeping an eye on all who entered, and in the road in front of private houses, protecting their inhabitants.[59]

This function would appear to have some relationship with the iconographic association of Hecate with keys, and might also relate to her appearance with two torches, which when positioned on either side of a gate or door illuminated the immediate area and allowed visitors to be identified. "In Byzantium small temples in her honour were placed close to the gates of the city. Hecate's importance to Byzantium was above all as a deity of protection. When Philip of Macedon was about to attack the city, according to the legend she alerted the townspeople with her ever present torches, and with her pack of dogs, which served as her constant companions."[60] This suggests that Hecate's close association with dogs derived in part from the use of watchdogs, who, particularly at night, raised an alarm when intruders approached. Watchdogs were used extensively by Greeks and Romans.[61]

Cult images and altars of Hecate in her triplicate or trimorphic form were placed at three-way crossroads (though they also appeared before private homes and in front of city gates).[10] In what appears to be a 7th-century indication of the survival of cult practices of this general sort, Saint Eligius, in his Sermo warns the sick among his recently converted flock in Flanders against putting "devilish charms at springs or trees or crossroads",[62] and, according to Saint Ouen would urge them "No Christian should make or render any devotion to the deities of the trivium, where three roads meet...".[63]

As a goddess of the underworld

Thanks to her association with boundaries and the liminal spaces between worlds, Hecate is also recognized as a chthonic (underworld) goddess. As the holder of the keys that can unlock the gates between realms, she can unlock the gates of death, as described in a 3rd-century BCE poem by Theocritus. In the 1st century CE, Virgil described the entrance to hell as "Hecate's Grove", though he says that Hecate is equally "powerful in Heaven and Hell." The Greek Magical Papyri describe Hecate as the holder of the keys to Tartaros.[28] Like Hermes, Hecate takes on the role of guardian not just of roads, but of all journeys, including the journey to the afterlife. In art and myth, she is shown, along with Hermes, guiding Persephone back from the underworld with her torches.[28]

By the 5th century BCE, Hecate had come to be strongly associated with ghosts, possibly due to conflation with the Thessalian goddess Enodia (meaning "traveller"), who travelled the earth with a retinue of ghosts and was depicted on coinage wearing a leafy crown and holding torches, iconography strongly associated with Hecate.[28]

As a goddess of witchcraft

By the 1st century CE, Hecate's chthonic and nocturnal character had led to her transformation into a goddess heavily associated with witchcraft, witches, magic, and sorcery. In Lucan's Pharsalia, the witch Erichtho invokes Hecate as "Persephone, who is the third and lowest aspect of Hecate, the goddess we witches revere", and describes her as a "rotting goddess" with a "pallid decaying body", who has to "wear a mask when [she] visit[s] the gods in heaven."[28]

Like Hecate, "[t]he dog is a creature of the threshold, the guardian of doors and portals, and so it is appropriately associated with the frontier between life and death, and with demons and ghosts which move across the frontier. The yawning gates of Hades were guarded by the monstrous watchdog Cerberus, whose function was to prevent the living from entering the underworld, and the dead from leaving it."[64]

As a goddess of the moon

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Hecate was seen as a triple deity, identified with the goddesses Luna (moon) in the sky and Diana (hunting) on the earth, while she represents the Underworld.[65] Hecate's association with Helios in literary sources and especially in cursing magic has been cited as evidence for her lunar nature, although this evidence is pretty late; no artwork before the Roman period connecting Hecate to the Moon exists.[66] Nevertheless, the Homeric Hymn to Demeter shows Helios and Hecate informing Demeter of Persephone's abduction, a common theme found in many parts of the world where the Sun and the Moon are questioned concerning events that happen on earth based on their ability to witness everything[66] and implies Hecate's capacity as a moon goddess in the hymn.[67] Another work connecting Hecate to Helios possibly as a moon goddess is Sophocles' lost play The Root Cutters, where Helios is described as Hecate's spear:

O Sun our lord and sacred fire, the spear of Hecate of the

roads, which she carries as she attends her mistress in the sky[68]

This speech from the Root Cutters may or may not be an intentional association of Hecate with the Moon.[69] In Seneca's Medea, the titular Medea invokes her patron Hecate whom she addresses as "moon, orb of the night" and "triple form".[70] Hecate and the moon goddess Selene were frequently identified with each other and a number of Greek and non-Greek deities;[71] the Greek Magical Papyri and other magical texts emphasize a syncretism between Selene-Hecate with Artemis and Persephone among others.[71] In Italy, the triple unity of the lunar goddesses Diana (the huntress), Luna (the moon) and Hecate (the underworld) became a ubiquitous feature in depictions of sacred groves, where Hecate/Trivia marked intersections and crossroads along with other liminal deities.[72] The Romans celebrated enthusiastically the multiple identities of Diana as Hecate, Luna and Trivia.[72]

From her father Perses, Hecate is often called “Perseis” (meaning “daughter of Perses”)[73][74] which is also the name of one of the Oceanid nymphs, Helios’ wife and Circe’s mother in other versions.[75] In one version of Hecate's parentage, she is the daughter of Perses not the son of Crius but the son of Helios, whose mother is the Oceanid Perse.[76] Karl Kerenyi noted the similarity between the names, perhaps denoting a chthonic connection among the two and the goddess Persephone;[77] it is possible that this epithet gives evidence of a lunar aspect of Hecate.[78] Fowler also noted that the pairing (i. e. Helios and Perse) made sense given Hecate’s association with the moon.[79] Mooney however notes that when it comes to the nymph Perse herself, there's no evidence of her actually being a moon goddess on her own right.[80]

Cult

Worship of Hecate existed alongside other deities in major public shrines and temples in antiquity, and she had a significant role as household deity.[81] Shrines to Hecate were often placed at doorways to homes, temples, and cities with the belief that it would protect from restless dead and other spirits. Home shrines often took the form of a small Hekataion, a shrine centred on a wood or stone carving of a triple Hecate facing in three directions on three sides of a central pillar. Larger Hekataions, often enclosed within small walled areas, were sometimes placed at public crossroads near important sites – for example, there was one on the road leading to the Acropolis.[82] Likewise, shrines to Hecate at three way crossroads were created where food offerings were left at the new moon to protect those who did so from spirits and other evils.[83]

Dogs were sacred to Hecate and associated with roads, domestic spaces, purification, and spirits of the dead. Dogs were also sacrificed to the road.[84] This can be compared to Pausanias' report that in the Ionian city of Colophon in Asia Minor a sacrifice of a black female puppy was made to Hecate as "the wayside goddess", and Plutarch's observation that in Boeotia dogs were killed in purificatory rites. Dogs, with puppies often mentioned, were offered to Hecate at crossroads, which were sacred to the goddess.[85]

History

The earliest definitive record of Hecate's worship dates to the 6th century B.C.E., in the form of a small terracotta statue of a seated goddess, identified as Hecate in its inscription. This and other early depictions of Hecate lack distinctive attributes that would later be associated with her, such as a triple form or torches, and can only be identified as Hecate thanks to their inscriptions. Otherwise, they are typically generic, or Artemis-like.[28]

Hecate's cult became established in Athens about 430 B.C.E. At this time, the sculptor Alcamenes made the earliest known triple-formed Hecate statue for use at her new temple. While this sculpture has not survived to the present day, numerous later copies are extant.[28] It has been speculated that this triple image, usually situated around a pole or pillar, was derived from earlier representations of the goddess using three masks hung on actual wooden poles, possibly placed at crossroads and gateways.[28]

Sanctuaries

Hecate was a popular divinity, and her cult was practiced with many local variations all over Greece and Western Anatolia. Caria was a major center of worship and her most famous temple there was located in the town of Lagina. The oldest known direct evidence of Hecate's cult comes from Selinunte (near modern-day Trapani in Sicily), where she had a temple in the 6th–5th centuries BC.[86]

There was a Temple of Hecate in Argolis:

Over against the sanctuary of Eileithyia is a temple of Hecate [the goddess probably here identified with the apotheosed Iphigenia, and the image is a work of Skopas. This one is of stone, while the bronze images opposite, also of Hecate, were made respectively by Polykleitos and his brother Naukydes.[87]

There were also a shrine to Hecate in Aigina, where she was very popular:

Of the gods, the Aiginetans worship most Hecate, in whose honour every year they celebrate mystic rites which, they say, Orpheus the Thrakian established among them. Within the enclosure is a temple; its wooden image is the work of Myron, and it has one face and one body. It was Alkamenes, in my opinion, who first made three images of Hecate attached to one another [in Athens].[88]

Aside from her own temples, Hecate was also worshipped in the sanctuaries of other gods, where she was apparently sometimes given her own space. A round stone altar dedicated to the goddess was found in the Delphinion (a temple dedicated to Apollo) at Miletus. Dated to the 7th century BCE, this is one of the oldest known artefacts dedicated to the worship of Hecate.[13] In association with her worship alongside Apollo at Miletus, worshipers used a unique form of offering: they would place stone cubes, often wreathes, known as γυλλοι (gylloi) as protective offerings at the door or gateway.[13][89] There was an area sacred to Hecate in the precincts of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, where the priests, megabyzi, officiated.[90] This sanctuary was called Hecatesion (Shrine of Hecate).[91] Hecate was also worshipped in the Temple of Athena in Titane: "In Titane there is also a sanctuary of Athena, into which they bring up the image of Koronis [mother of Asklepios] ... The sanctuary is built upon a hill, at the bottom of which is an Altar of the Winds, and on it the priest sacrifices to the winds one night in every year. He also performs other secret rites [of Hecate] at four pits, taming the fierceness of the blasts [of the winds], and he is said to chant as well the charms of Medea."[92] She was most commonly worshipped in nature, where she had many natural sanctuaries. An important sanctuary of Hecate was a holy cave on the island of Samothrake called Zerynthos:

In Samothrake there were certain initiation-rites, which they supposed efficacious as a charm against certain dangers. In that place were also the mysteries of the Korybantes [Kabeiroi] and those of Hekate and the Zerinthian cave, where they sacrificed dogs. The initiates supposed that these things save [them] from terrors and from storms.[93]

Cult at Lagina

Hecate's most important sanctuary was Lagina, a theocratic city-state in which the goddess was served by eunuchs.[6]

The temple is mentioned by Strabo:

Stratonikeia [in Karia, Asia Minor] is a settlement of Makedonians ... There are two temples in the country of the Stratonikeians, of which the most famous, that of Hecate, is at Lagina; and it draws great festal assemblies every year.[94]

Lagina, where the famous temple of Hecate drew great festal assemblies every year, lay close to the originally Macedonian colony of Stratonikeia, where she was the city's patron.[95] In Thrace she played a role similar to that of lesser-Hermes, namely a ruler of liminal regions, particularly gates, and the wilderness.

Cult at Byzantium

Hecate was greatly worshipped in Byzantium. She was said to have saved the city from Philip II of Macedon, warning the citizens of a night time attack by a light in the sky, for which she was known as Hecate Lampadephoros. The tale is preserved in the Suda.[lower-alpha 5]

As Hecate Phosphorus (the 'star' Venus) she is said to have lit the sky during the Siege of Philip II in 340 BCE, revealing the attack to its inhabitants. The Byzantines dedicated a statue to her as the "lamp carrier".[98] According to Hesychius of Miletus there was once a statue of Hecate at the site of the Hippodrome in Constantinople.[99]

Hecate's island

Hecate's island (Ἑκάτης νήσου) also called Psamite (Ψαμίτη), was an islet in the vicinity of Delos. It was called Psamite, because Hecate was honoured with a cake, which was called psamiton (ψάμιτον).[100] The island is the modern Megalos (Great) Reumatiaris.[101]

Deipnon

The Athenian Greeks honoured Hecate during the Deipnon. In Greek, deipnon means the evening meal, usually the largest meal of the day. Hecate's Deipnon is, at its most basic, a meal served to Hecate and the restless dead once a lunar month[102] during the new moon. The Deipnon is always followed the next day by the Noumenia,[103] when the first sliver of the sunlit Moon is visible, and then the Agathos Daimon the day after that.

The main purpose of the Deipnon was to honour Hecate and to placate the souls in her wake who "longed for vengeance."[104] A secondary purpose was to purify the household and to atone for bad deeds a household member may have committed that offended Hecate, causing her to withhold her favour from them. The Deipnon consists of three main parts: 1) the meal that was set out at a crossroads, usually in a shrine outside the entryway to the home[105] 2) an expiation sacrifice,[106] and 3) purification of the household.[107]

Epithets

Hecate was known by a number of epithets:

- Apotropaia (Ἀποτρόπαια), the one that turns away/protects.[108]

- Brimo (Βριμώ), angry/terrifying. [109]

- Chthonia (Χθωνία), of the earth/underworld.[110]

- Enodia (Ἐννοδία), she on the way/road.[111]

- Klêidouchos (Κλειδοῦχος), holding the keys.[112]

- Kourotrophos (Κουροτρόφος), nurse of children.[112]

- Krokopeplos (Κροκόπεπλος), saffron cloaked.[113]

- Melinoe (Μηλινόη).[114]

- Phosphoros, Lampadephoros (Φωσφόρος, Λαμπαδηφόρος), bringing or bearing light.[112]

- Propolos (Πρόπολος), who serves/attends.[112]

- Propulaia/Propylaia (Προπύλαια), before the gate.[115]

- Soteria (Σωτηρία), savior.[9]

- Trimorphe (Τρίμορφη), three-formed.[112]

- Triodia/Trioditis (Τριοδία, Τριοδίτης), who frequents crossroads.[112]

Historical and literary sources

Archaic period

Hecate has been characterized as a pre-Olympian chthonic goddess. The first literature mentioning Hecate is the Theogony (c. 700 BCE) by Hesiod:

And [Asteria] conceived and bore Hecate whom Zeus the son of Cronos honored above all. He gave her splendid gifts, to have a share of the earth and the unfruitful sea. She received honor also in starry heaven, and is honored exceedingly by the deathless gods. For to this day, whenever any one of men on earth offers rich sacrifices and prays for favor according to custom, he calls upon Hecate. Great honor comes full easily to him whose prayers the goddess receives favorably, and she bestows wealth upon him; for the power surely is with her. For as many as were born of Earth and Ocean amongst all these she has her due portion. The son of Cronos did her no wrong nor took anything away of all that was her portion among the former Titan gods: but she holds, as the division was at the first from the beginning, privilege both in earth, and in heaven, and in sea.[116]

According to Hesiod, she held sway over many things:

Whom she will she greatly aids and advances: she sits by worshipful kings in judgement, and in the assembly whom she will is distinguished among the people. And when men arm themselves for the battle that destroys men, then the goddess is at hand to give victory and grant glory readily to whom she will. Good is she also when men contend at the games, for there too the goddess is with them and profits them: and he who by might and strength gets the victory wins the rich prize easily with joy, and brings glory to his parents. And she is good to stand by horsemen, whom she will: and to those whose business is in the grey discomfortable sea, and who pray to Hecate and the loud-crashing Earth-Shaker, easily the glorious goddess gives great catch, and easily she takes it away as soon as seen, if so she will. She is good in the byre with Hermes to increase the stock. The droves of kine and wide herds of goats and flocks of fleecy sheep, if she will, she increases from a few, or makes many to be less. So, then, albeit her mother's only child, she is honored amongst all the deathless gods. And the son of Cronos made her a nurse of the young who after that day saw with their eyes the light of all-seeing Dawn. So from the beginning she is a nurse of the young, and these are her honours.[117]

Hesiod's inclusion and praise of Hecate in the Theogony has been troublesome for scholars, in that he seems to hold her in high regard, while the testimony of other writers, and surviving evidence, suggests that this may have been the exception. One theory is that Hesiod's original village had a substantial Hecate following and that his inclusion of her in the Theogony was a way of adding to her prestige by spreading word of her among his readers.[119] Another theory is that Hecate was mainly a household god and humble household worship could have been more pervasive and yet not mentioned as much as temple worship.[120] In Athens, Hecate, along with Zeus, Hermes, Athena, Hestia, and Apollo, were very important in daily life as they were the main gods of the household.[7] However, it is clear that the special position given to Hecate by Zeus is upheld throughout her history by depictions found on coins of Hecate on the hand of Zeus[121] as highlighted in more recent research presented by d'Este and Rankine.[122]

In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter (composed c. 600 BCE), Hecate is called "tender-hearted", an epithet perhaps intended to emphasize her concern with the disappearance of Persephone, when she assisted Demeter with her search for Persephone following her abduction by Hades, suggesting that Demeter should speak to the god of the Sun, Helios. Subsequently, Hecate became Persephone's companion on her yearly journey to and from the realms of Hades, serving as a psychopomp. Because of this association, Hecate was one of the chief goddesses of the Eleusinian Mysteries, alongside Demeter and Persephone,[1] and there was a temple dedicated to her near the main sanctuary at Eleusis.[28]

Classical period

Variations in interpretations of Hecate's roles can be traced in classical Athens. In two fragments of Aeschylus she appears as a great goddess. In Sophocles and Euripides she is characterized as the mistress of witchcraft and the Keres.

One surviving group of stories suggests how Hecate might have come to be incorporated into the Greek pantheon without affecting the privileged position of Artemis. Here, Hecate is a mortal priestess often associated with Iphigenia. She scorns and insults Artemis, who in retribution eventually brings about the mortal's suicide.[119]

In the Argonautica, a 3rd-century BCE Alexandrian epic based on early material,[123] Jason placates Hecate in a ritual prescribed by Medea, her priestess: bathed at midnight in a stream of flowing water, and dressed in dark robes, Jason is to dig a round pit and over it cut the throat of a ewe, sacrificing it and then burning it whole on a pyre next to the pit as a holocaust. He is told to sweeten the offering with a libation of honey, then to retreat from the site without looking back, even if he hears the sound of footsteps or barking dogs.[124] All these elements betoken the rites owed to a chthonic deity.

Late Antiquity

During the Gigantomachy, Hecate fought by the side of the Olympian gods, and slew the giant Clytius using her torches.[125] Hecate is depicted fighting Clytius in the east frieze of the Gigantomachy, in the Pergamon Altar next to Artemis;[126] she appears with a different weapon in each of her three right hands, a torch, a sword and a lance.[3] Her fight with the Giant appears in a number of ancient vase paintings and other artwork.[33][127]

Hecate is the primary feminine figure in the Chaldean Oracles (2nd–3rd century CE),[128] where she is associated in fragment 194 with a strophalos (usually translated as a spinning top, or wheel, used in magic) "Labour thou around the Strophalos of Hecate."[129] This appears to refer to a variant of the device mentioned by Psellus.[130]

In Hellenistic syncretism, Hecate also became closely associated with Isis. Lucius Apuleius in The Golden Ass (2nd century) equates Juno, Bellona, Hecate and Isis:

Some call me Juno, others Bellona of the Battles, and still others Hecate. Principally the Ethiopians which dwell in the Orient, and the Egyptians which are excellent in all kind of ancient doctrine, and by their proper ceremonies accustomed to worship me, do call me Queen Isis.[131]

In the syncretism during Late Antiquity of Hellenistic and late Babylonian ("Chaldean") elements, Hecate was identified with Ereshkigal, the underworld counterpart of Inanna in the Babylonian cosmography. In the Michigan magical papyrus (inv. 7), dated to the late 3rd or early 4th century CE, Hecate Erschigal is invoked against fear of punishment in the afterlife.[132]

Hecate is also referenced in the Gnostic text Pistis Sophia.[133]

Parents, consorts and children

In the earliest written source mentioning Hecate, Hesiod emphasized that she was an only child, the daughter of Perses and Asteria, the sister of Leto (the mother of Artemis and Apollo). Grandmother of the three cousins was Phoebe[117] the ancient Titan goddess whose name was often used for the moon goddess.[134][135] In various later accounts, Hecate was given different parents.[136] She was said to be the daughter of Zeus by either Asteria, according to Musaeus,[137] Hera, thus identified with Angelos,[138] or Pheraea, daughter of Aeolus;[139] the daughter of Aristaeus the son of Paion, according to Pherecydes;[140] the daughter of Nyx, according to Bacchylides;[137] the daughter of Perses, the son of Helios, by an unknown mother, according to Diodorus Siculus;[76] while in Orphic literature, she was said to be the daughter of Demeter[141] or Leto[142] or even Tartarus.[143]

As a virgin goddess, she remained unmarried and had no regular consort, though some traditions named her as the mother of Scylla[144] through either Phorbas[145][lower-alpha 6] or Phorcys.[146]

Sometimes she is also stated to be the mother (by Aeëtes[76]) of the goddess Circe and the sorceress Medea,[147] who in later accounts was herself associated with magic while initially just being a herbalist goddess, similar to how Hecate's association with Underworld and Mysteries had her later converted into a deity of witchcraft.

Once, Hermes chased Hecate (or Persephone) with the aim to rape her; but the goddess snored or roared in anger, frightening him off so that he desisted, hence her earning the name "Brimo" ("angry").[148]

Genealogy

| Hecate's family tree [149] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

Strmiska (2005) claimed that Hecate, conflated with the figure of Diana, appears in late antiquity and in the Early Middle Ages as part of an "emerging legend complex" known as "The Society of Diana"[154] associated with gatherings of women, the Moon, and witchcraft that eventually became established "in the area of Northern Italy, southern Germany, and the western Balkans."[155] This theory of the Roman origins of many European folk traditions related to Diana or Hecate was explicitly advanced at least as early as 1807[156] and is reflected in etymological claims by early modern lexicographers from the 17th to the 19th century, connecting hag, hexe "witch" to the name of Hecate.[157] Such derivations are today proposed only by a minority[158] [159] A medieval commentator has suggested a link connecting the word "jinx" with Hecate: "The Byzantine polymath Michael Psellus [...] speaks of a bullroarer, consisting of a golden sphere, decorated throughout with symbols and whirled on an oxhide thong. He adds that such an instrument is called a iunx (hence "jinx"), but as for the significance says only that it is ineffable and that the ritual is sacred to Hecate."[160]

Shakespeare mentions Hecate both before the end of the 16th century (A Midsummer Night's Dream, 1594–1596), and just after, in Macbeth (1605): specifically, in the title character's "dagger" soliloquy: "Witchcraft celebrates pale Hecate's offerings..."[161] Shakespeare mentions Hecate also in King Lear. While disclaiming all his paternal care for Cordelia, Lear says, "The mysteries of Hecate and the night, By all the operations of the orbs From whom we do exist and cease to be, Here I disclaim all my paternal care" (The Arden Shakespeare, King Lear, Page no.165)

Modern reception

.jpg.webp)

In 1929, Lewis Brown, an expert on religious cults, connected the 1920s Blackburn Cult (also known as, "The Cult of the Great Eleven,") with Hecate worship rituals. He noted that the cult regularly practiced dog sacrifice and had secretly buried the body of one of its "queens" with seven dogs.[162] Researcher Samuel Fort noted additional parallels, to include the cult's focus on mystic and typically nocturnal rites, its female dominated membership, the sacrifice of other animals (to include horses and mules), a focus on the mystical properties of roads and portals, and an emphasis on death, healing, and resurrection.[163]

As a "goddess of witchcraft", Hecate has been incorporated in various systems of modern witchcraft, Wicca, and neopaganism,[164] in some cases associated with the Wild Hunt of Germanic tradition,[165] in others as part of a reconstruction of specifically Greek polytheism, in English also known as "Hellenismos".[166] In Wicca, Hecate has in some cases become identified with the "crone" aspect of the "Triple Goddess".[167]

See also

- Hecate (journal)

- Janus – Roman god

- Lampad – Nymphs of the Underworld in Greek mythology

Notes

- Pronounced /ˈhɛkəti/ HEK-ə-tee; older form Hecat /ˈhɛkɪt/ HEK-it; Ancient Greek: Ἑκάτη, romanized: Hekátē, Attic Greek pronunciation: [hekátɛː], Koine Greek pronunciation: [heˈkati]; Doric Greek: Ἑκάτᾱ, romanized: Hekátā, pronounced [hekátaː]; Latin: Hecatē [ˈhɛkateː] or Hecata [ˈhɛkata].

- Berg 1974, p. 128: Berg comments on Hecate's endorsement of Roman hegemony in her representation on the pediment at Lagina solemnising a pact between a warrior (Rome) and an amazon (Asia).

-

Berg's argument for a Greek origin rests on three main points:

- This statue is in the British Museum, inventory number 816.

-

"In 340 B.C., however, the Byzantines, with the aid of the Athenians, withstood a siege successfully, an occurrence the more remarkable as they were attacked by the greatest general of the age, Philip of Macedon. In the course of this beleaguerment, it is related, on a certain wet and moonless night the enemy attempted a surprise, but were foiled by reason of a bright light which, appearing suddenly in the heavens, startled all the dogs in the town and thus roused the garrison to a sense of their danger. To commemorate this timely phenomenon, which was attributed to Hecate, they erected a public statue to that goddess [...]".[96]

- The ancient text is corrupted; an alternative correction of the name into 'Phoebus' (that is, Apollo) has been also suggested. It could also be that the fragment reads 'Phorcys', agreeing with Acusilaus' version.[146]

References

- Edwards, Charles M. (July 1986). "The Running Maiden from Eleusis and the Early Classical Image of Hekate". American Journal of Archaeology. Boston, Massachusetts: Archaeological Institute of America. 90 (3): 307–318. doi:10.2307/505689. JSTOR 505689. S2CID 193054943.

- Merriam-Webster 1995, p. 527.

- Seyffert, s.v. Hecate

- d'Este, Sorita & Rankine, David, Hekate Liminal Rites, Avalonia, 2009.

- trans. M.L. West (1988). Hesiod Theogony and Works and Days. New York: Oxforx World's Classics. pp. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-953831-7.

- Burkert, Walter (1987). Greek Religion: Archaic and classical. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. p. 171. ISBN 0-631-15624-0.

- Panopoulos, Christos Pandion. "Hellenic Household Worship". LABRYS.

- "Bryn Mawr Classical Review 02.06.11". Bmcr.brynmawr.edu. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, Hekate Soteira, Scholars Press, 1990.

- Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds. (1996). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Third ed.). New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 671. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- Green, p. 133

- At least in the case of Hesiod's use, see Clay, Jenny Strauss (2003). Hesiod's Cosmos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-521-82392-7. Clay lists a number of researchers who have advanced some variant of the association between Hecate's name and will (e.g. Walcot (1958), Neitzel (1975), Derossi (1975)). The researcher is led to identify "the name and function of Hecate as the one 'by whose will' prayers are accomplished and fulfilled." This interpretation also appears in Liddell-Scott, A Greek English Lexicon, in the entry for Hecate, which is glossed as "lit. 'she who works her will'"

- Mooney, Carol M., "Hekate: Her Role and Character in Greek Literature from before the Fifth Century B.C." (1971). Open Access Dissertations and heses. Paper 4651.

- Wheelwright, P. E. (1975). Metaphor and Reality. Bloomington. p. 144. ISBN 0-253-20122-5.

- Fairbanks, Arthur. A Handbook of Greek Religion. American Book Company, 1910.

- R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek (2009), Brill, p. 396.

- McKechnie, Paul R.; Guillaume, Philippe (2008). Ptolemy the second Philadelphus and his world. BRILL. p. 133. ISBN 978-90-04-17089-6.

- Heka

- Kraus, Theodor (1960). Hekate: Studien zu Wesen u. Bilde der Göttin in Kleinasien u. Griechenland (in German). Heidelberg, DE.

- Berg (1974) p. 134

- Kraus 1960, p. 52; list pp. 166 ff.

- Berg 1974, p. 129.

- Bachvarova, Mary (May 2010). "Hecate: An Anatolian sun-goddess of the underworld". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1608145.

- Golding, Arthur (1567). "Book Seven". Ovid's Metamorphoses. ISBN 9781406792416.

- Marlowe, Christopher (c. 1603) [first published 1604; performed earlier]. Doctor Faustus. act III, scene 2, line 21 – via Google Books.

Pluto's blue fire and Hecat's tree

Shakespeare, William (c. 1595) [c. 1594–1596]. A Midsummer Night's Dream. act V, scene 1, line 384.By the triple Hecat's team

Shakespeare, William (c. 1605) [c. 1603–1607]. Macbeth. act III, scene 5, line 1.Why, how now, Hecat!

Jonson, Ben (1641) [c. 1637]. "act II, scene 3, line 668". The Sad Shepherd.our dame Hecat

- Webster, Noah (1866). A Dictionary of the English Language (10th ed.).

Rules for pronouncing the vowels of Greek and Latin proper names", p. 9: "Hecate ..., pronounced in three syllables when in Latin, and in the same number in the Greek word Ἑκάτη; in English is universally contracted into two, by sinking the final e. Shakespeare seems to have begun, as he has now confirmed, this pronunciation, by so adapting the word in Macbeth ... . And the play-going world, who form no small portion of what is called the better sort of people, have followed the actors in this world, and the rest of the world have followed them.

"Hec'ate". Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. 1894.3 syl. in Greek, 2 in Eng.

- Lewis Richard Farnell, (1896). "Hekate: Representations in Art", The Cults of the Greek States. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p. 549.

- Rabinowitz, Jacob. The Rotting Goddess: The origin of the witch in classical antiquity's demonization of fertility religion. Autonomedia, 1998.

- Hekate Her Sacred Fires, ed. Sorita d'Este, Avalonia, 2010

- Pausanias 2.22.7

- Yves Bonnefoy, Wendy Doniger, Roman and European Mythologies, University of Chicago Press, 1992, p. 195.

- Johnston, p. 213

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary, p. 650

- Alberta Mildred Franklin, The Lupercalia, Columbia University, 1921, p67

- "page 21 (image of Hecate attended by a dog)". timerift.net. Archived from the original on 24 October 2011.

- "Images of goddesses". Eidola.eu. 28 February 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles (1999). Restless Dead. University of California Press. pp. 211–212.

- "Lycophron, Alexandra". Classical texts library. Theoi.

- Antoninus Liberalis (1992). Metamorphoses. Translated by Celoria, Francis. Psychology Press. 29.

- Aelian (1958). On the Characteristics of Animals by Aelian. Translated by Scholfield, Alwyn Faber. Harvard University Press.

- Bohn, H.G. (1854). The Learned Banqueters. Translated by Yonge, Charles Duke.

- Parker, Robert (1990). Miasma: Pollution and purification in early Greek religion. Oxford University Press. pp. 362–363.

- Leake, William Martin (1841). The Topography of Athens. London, UK. p. 492.

- Davidson, Alan (2002). Mediterranean Seafood. Ten Speed Press. p. 92.

- Bonnefoy, Yves; Doniger, Wendy (1992). Roman and European Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. p. 195.

"Hecate". Encyclopædia Britannica (article). 1823. - Armour, Robert A. (2001). Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. p. 116.

- Varner, Gary R. (2007). Creatures in the Mist: Little people, wild men, and spirit beings around the world: A study in comparative mythology. New York, NY: Algora Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-87586-546-1.

- Krappe, Alexander Haggerty (1932). "La poursuite du Gilla Dacker et les Dioscures celtiques" [The pursuit of the Gilla Dacker and the Celtic dioscuri]. Revue Celtique (in French). 49: 102.

- R. L. Hunter, The Argonautica of Apollonius, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 142, citing Apollonius of Rhodes.

- Daniel Ogden, Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 82–83.

- Matthew Suffness (Ed.), Taxol: Science and Applications, CRC Press, 1995, p. 28.

- Frederick J. Simoons, Plants of Life, Plants of Death, University of Wisconsin Press, 1998, p. 143; Fragkiska Megaloudi, Plants and Diet in Greece From Neolithic to Classic Periods, Archaeopress, 2006, p. 71.

- Frieze, Henry; Dennison, Walter (1902). Virgil's Aeneid. New York: American Book Company. pp. N111.

- "Hecate had a "botanical garden" on the island of Colchis where the following alkaloid plants were kept: Akoniton (Aconitum napellus), Diktamnon (Dictamnus albus), Mandragores (Mandragora officinarum), Mekon (Papaver somniferum), Melaina (Claviceps pupurea), Thryon (Atropa belladona), and Cochicum [...]" Margaret F. Roberts, Michael Wink, Alkaloids: Biochemistry, Ecology, and Medicinal Applications, Springer, 1998, p. 16.

- Robert Graves, The Greek Myths, Penguin Books, 1977, p. 154.

- Frederick J. Simoons, Plants of Life, Plants of Death, University of Wisconsin Press, 1998, pp. 121–124.

- Bonnie MacLachlan, Judith Fletcher, Virginity Revisited: Configurations of The Unpossessed Body, University of Toronto Press, 2007, p. 14.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, 1999, p. 209.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, 1999, p. 208.

- Vasiliki Limberis, Divine Heiress: The Virgin Mary And The Creation of Christian Constantinople, Routledge, 1994, pp. 126–127.

- Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds. (1996). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Third ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 490. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- Amanda Porterfield, Healing in the history of Christianity, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 72.

- Saint Ouen, Vita Eligii book II.16 Archived 20 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- Richard Cavendish, The Powers of Evil in Western Religion, Magic and Folk Belief, Routledge, 1975, p. 62.

- Servius, Commentary on the Aeneid 6.118; Green, C. M. C. (2007). Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Queen of the Night: Rediscovering the Celtic Moon Goddess pp 62-63

- Athanassakis and Wolkow, p. 90

- Loeb Classical Library, 1994, Sophocles: Fragments, p. 271, Oxford University.

- Gantz, p. 27

- Seneca, Medea 750-753

- Hordern, J. H. “Love Magic and Purification in Sophron, PSI 1214a, and Theocritus’ ‘Pharmakeutria.’” The Classical Quarterly 52, no. 1 (2002): 165

- Bergmann, Bettina, Joseph Farrell, Denis Feeney, James Ker, Damien Nelis, and Celia Schultz. “An Exciting Provocation: John F. Miller’s ‘Apollo, Augustus, and the Poets.’” Vergilius (1959-) 58 (2012): 10–11

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 3.478; Ovid, Metamorphoses 7.74; Seneca, Medea 812

- Smith, s. v. Hecate

- Homer, Odyssey 10.135; Hesiod, Theogony 956; Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 4.591; Apollodorus, 1.9.1; Cicero, De Natura Deorum 48.4; Hyginus, Fabulae Preface

- Diodorus Siculus, Historic Library 4.45.1

- Karl Kerenyi, The Gods of the Greeks, 1951, pp 192-193

- The Classical Review vol. 9, pp 391–392

- Fowler, p. 16, vol. II

- Mooney, p. 58

- Aune, David Edward (2006). Apocalypticism, Prophecy and Magic in Early Christianity: Collected Essays. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 356ff. ISBN 3161490207.

- Wycherley, R. (1970). Minor Shrines in Ancient Athens. Phoenix, 24(4), 283–295. doi:10.2307/1087735

- "CULT OF HEKATE : Ancient Greek religion". Theoi.com. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- As Sterckx (2002) observes, "The use of dog sacrifices at the gates and doors of the living and the dead as well as its use in travel sacrifices suggest that dogs were perceived as daemonic animals operating in the liminal or transitory realm between the domestic and the unknown, danger-stricken outside world". Roel Sterckx, The Animal and The Daemon in Early China, State University of New York Press, 2002, pp 232–233. Sterckx explicitly recognizes the similarities between these ancient Chinese views of dogs and those current in Greek and Roman antiquity, and goes on to note "Dog sacrifice was also a common practice among the Greeks where the dog figured prominently as a guardian of the underworld." (Footnote 113, p318)

- Simoons, Frederick J. (1994). Eat Not This Flesh: Food Avoidances from Prehistory to the Present. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 233–234. ISBN 978-0299142544.

- Redazione ANSA. "Oldest ever trace of Hekate cult found". 16 January 2018.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 22. 7

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.30.2 (trans. Jones)

- J.-M. Carbon, S. Peels and V. Pirenne-Delforge, Collection of Greek Ritual Norms (CGRN), Liège 2015– (http://cgrn.ulg.ac.be, consulted in [2019]).

- Strabo, Geography, 14.1.23

- Strabo, Geography 14. 1. 23 (trans. Jones)

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.12.1

- Suidas s.v. All' ei tis humôn en Samothraikei memuemenos esti

- Strabo, Geography 14.2.15 (trans. Jones)

- Strabo, Geography 14.2.25; Kraus 1960.

- Holmes, William Gordon (2003). The Age of Justinian and Theodora. pp. 5–6.

- Limberis, Vasiliki (1994). Divine Heiress. Routledge. pp. 126–127.

- Russell, Thomas James (2017). Byzantium and the Bosporus. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780198790525.

- Patria of Constantinople

- Suda, epsilon, 365

- Travels in Greece and Turkey: Undertaken by Order of Louis XVI, and with the Authority of the Ottoman Court, Volume 2, 1801, p.309

- The play Plutus by Aristophanes (388 BCE), line 594 any translation will do or Benjamin Bickley Rogers is fine

- Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 65, No.2, 1972 pages 291–297

- These are the biaiothanatoi, aoroi and ataphoi (cf. Rohde, i. 264 f., and notes, 275–277, ii. 362, and note, 411–413, 424–425), whose enthumion, the quasi-technical word designating their longing for vengeance, was much dreaded. See Heckenbach, p. 2776 and references.

- Antiphanes, in Athenaeus, 313 B (2. 39 K), and 358 F; Melanthius, in Athenaeus, 325 B. Plato, Com. (i. 647. 19 K), Apollodorus, Melanthius, Hegesander, Chariclides (iii. 394 K), Antiphanes, in Athenaeus, 358 F; Aristophanes, Plutus, 596.

- Hekate's Suppers, by K. F. Smith. Chapter in the book The Goddess Hekate: Studies in Ancient Pagan and Christian Philosophy edited by Stephen Ronan. Pages 57 to 64

- Roscher, 1889; Heckenbach, 2781; Rohde, ii. 79, n. 1. also Ammonius (p. 79, Valckenaer)

- Alberta Mildred Franklin, The Lupercalia, Columbia University, 1921, p. 68.

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 3.1194

- Jon D. Mikalson, Athenian Popular Religion, UNC Press, 1987, p. 76.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, 1999, pp. 208–209.

- Liddell-Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon.

- Adam Forrest, The Orphic Hymn to Hekate, Hermetic Fellowship, 1992.

- Ivana Petrovic, Von den Toren des Hades zu den Hallen des Olymp (Brill, 2007), p. 94; W. Schmid and O. Stählin, Geschichte der griechischen Literatur (C.H. Beck, 1924, 1981), vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 982; W.H. Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie (Leipzig: Teubner, 1890–94), vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 16.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, 1999, p. 207.

- Hesiod, Theogony 411–425.

- Hesiod, Theogony 429–452.

- Foreign Influence on Ancient India, Krishna Chandra Sagar, Northern Book Centre, 1992

- Johnston, Sarah Iles, (1991). Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. ISBN 0-520-21707-1

- Household and Family Religion in Antiquity by John Bodel and Saul M. Olyan, page 221, published by John Wiley & Sons, 2009

- "Baktria, Kings, Agathokles, ancient coins index with thumbnails". WildWinds.com. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- d'Este & Rankine, Hekate Liminal Rites, Avalonia, 2009

- "The legend of the Argonauts is among the earliest known to the Greeks," observes Peter Green, The Argonautika, 2007, Introduction, p. 21.

- Apollonios Rhodios (tr. Peter Green), The Argonautika, University of California Press, 2007, p140

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Library 1.6.2

- The J. Paul Getty Museum, p. 101

- A collection of vase-paintings of Hecate fighting Clytius can be seen here.

- The Chaldean Oracles is a collection of literature that date from somewhere between the 2nd century and the late 3rd century, the recording of which is traditionally attributed to Julian the Chaldaean or his son, Julian the Theurgist. The material seems to have provided background and explanation related to the meaning of these pronouncements, and appear to have been related to the practice of theurgy, pagan magic that later became closely associated with Neoplatonism, seeHornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds. (1996). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Third ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- English translation used here from: William Wynn Wescott (tr.), The Chaldean Oracles of Zoroaster, 1895.

- "A top of Hekate is a golden sphere enclosing a lapis lazuli in its middle that is twisted through a cow-hide leather thong and having engraved letters all over it. [Diviners] spin this sphere and make invocations. Such things they call charms, whether it is the matter of a spherical object, or a triangular one, or some other shape. While spinning them, they call out unintelligible or beast-like sounds, laughing and flailing at the air. [Hekate] teaches the taketes to operate, that is the movement of the top, as if it had an ineffable power. It is called the top of Hekate because it is dedicated to her. In her right hand she held the source of the virtues. But it is all nonsense." As quoted in Frank R. Trombley, Hellenic Religion and Christianization, C. 370–529, Brill, 1993, p. 319.

- Apuleius, The Golden Ass 11.47.

- Hans Dieter Betz, "Fragments from a Catabasis Ritual in a Greek Magical Papyrus", History of Religions 19,4 (May 1980):287–295). The goddess appears as Hecate Erschigal only in the heading: in the spell itself only Erschigal is called upon with protective magical words and gestures.

- George R. S. Mead (1963). "140". Pistis Sophia. Jazzybee Verlag. ISBN 9783849687090. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- Boyle, p. 147

- Gordon MacDonald Kirkwood, A Short Guide to Classical Mythology, p. 88

- Gantz, p. 26.

- Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius' Argonautica 3.467

- Scholia on Theocritus 2.12

- Scholia on Theocritus 2.36; Tzetzes ad Lycophron Alexandra 1175

- Pherecydes, FHG 1 frag. 10

- Scholiast on Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 3.467 = Pherecydes, fr. 44 Fowler = FGrHist 3 fr. 44 = Vorsokr. 2 B 16 = Bacchylides, fr. 1 B Snell-Maehler = Orphic fr. 41 Kern.

- Proclus, Commentary on Plato's Cratylus 406 b (p. 106, 25 Pasqu.) [= Orphic fr. 188 Kern] [= OF 317 Bernabé]; West 1983, pp. 266, 267. The fragment is as follows: "Straightaway divine Hecate, the daughter of lovely-haired Leto, approached Olympus, leaving behind the limbs of the child."

- Orphic Argonautica 977

- Joseph Eddy Fontenrose, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins, Biblo & Tannen Publishers, 1974, p. 96.

- Hesiod fr. 200 Most [= fr. 262 MW] (Most, pp. 310, 311).

- Acusilaus. fr. 42 Fowler (Fowler, p. 32).

- Grimal; Smith.

- Tzetzes ad Lycophron 1176, 1211; Heslin, p. 39

- Hesiod, Theogony 132–138, 337–411, 453–520, 901–906, 915–920; Caldwell, pp. 8–11, tables 11–14.

- Although usually the daughter of Hyperion and Theia, as in Hesiod, Theogony 371–374, in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (4), 99–100, Selene is instead made the daughter of Pallas the son of Megamedes.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 507–511, Clymene, one of the Oceanids, the daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at Hesiod, Theogony 351, was the mother by Iapetus of Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus, while according to Apollodorus, 1.2.3, another Oceanid, Asia was their mother by Iapetus.

- According to Plato, Critias, 113d–114a, Atlas was the son of Poseidon and the mortal Cleito.

- In Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 18, 211, 873 (Sommerstein, pp. 444, 445 n. 2, 446, 447 n. 24, 538, 539 n. 113) Prometheus is made to be the son of Themis.

- Magliocco, Sabina. (2009). Aradia in Sardinia: The Archaeology of a Folk Character. Pp. 40–60 in Ten Years of Triumph of the Moon. Hidden Publishing.

- Michael Strmiska, Modern paganism in world cultures, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 68.

- Francis Douce, Illustrations of Shakspeare, and of Ancient Manners, 1807, p. 235-243.

- John Minsheu and William Somner (17th century), Edward Lye of Oxford (1694–1767), Johann Georg Wachter, Glossarium Germanicum (1737), Walter Whiter, Etymologicon Universale (1822)

- e.g. Gerald Milnes, Signs, Cures, & Witchery, Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2007, p. 116; Samuel X. Radbill, "The Role of Animals in Infant Feeding", in American Folk Medicine: A Symposium Ed. Wayland D. Hand. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

- "Many have been caught by the obvious resemblance of the Gr. Hecate, but the letters agree to closely, contrary to the laws of change, and the Mid. Ages would surely have had an unaspirated Ecate handed down to them; no Ecate or Hecate appears in the M. Lat. or Romance writings in the sense of witch, and how should the word have spread through all German lands?" Jacob Grimm, Teutonic Mythology, 1835, (English translation 1900). The actual etymology of hag is Germanic and unrelated to the name of Hecate. See e.g. Mallory, J.P, Adams, D.Q. The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press, 2006. p. 223

- Mark Edwards, Neoplatonic saints: the Lives of Plotinus and Proclus by their Students, Liverpool University Press, 2000, p. 100; Writing at some length about the ancient greek 'iunx' Marcel Detienne never mentions any connection to Hecate, see Detienne M, The Gardens of Adonis, Princeton UP, 1994, pp.83–9..

- "No Fear Shakespeare: Macbeth: Act 2, Scene 1, Page 2".

- Weird Rituals Laid to Primitive Minds, Los Angeles Examiner, 14 October 1929.

- Cult of the Great Eleven, Samuel Fort, 2014, 320 pages. ASIN B00OALI9O4

- e.g.Sabina Magliocco, Witching Culture: Folklore and Neopaganism in America, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004, p79

- James R. Lewis, Witchcraft Today: An Encyclopedia of Wiccan and Neopagan Traditions, 1999, pp 303–304; For a 'Moon magick' reference to Hecate as "Lady of the Wild Hunt and witchcraft" see: D. J. Conway, Moon Magick: Myth & Magic, Crafts & Recipes, Rituals & Spells, Llewellyn, 1995, p157

- Hellenion (USA) "Hellenion".. "Hekate's Deipnon – Temenos".

- E.g. Wilshire, Donna (1994). Virgin mother crone: myths and mysteries of the triple goddess. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International. p. 213. ISBN 0-89281-494-2..

Sources

Primary sources

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica, with an English translation by R. C. Seaton. Loeb Classical Library 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1912.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Orphic Argonautica, translated by Jason Colavito, derived from his text at argonauts-book.com, 2011.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, translated by Brookes More (1859-1942), from the Cornhill edition of 1922.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Strabo, The Geography of Strabo. Edition by H.L. Jones. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

Secondary sources

- Athanassakis, Apostolos N., and Benjamin M. Wolkow, The Orphic Hymns, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1-4214-0882-8. Google Books.

- Berg, William, "Hecate: Greek or "Anatolian"?", Numen 21.2 (August 1974:128-40)

- Burkert, Walter, 1985. Greek Religion (Cambridge: Harvard University Press) Published in the UK as Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, 1987. (Oxford: Blackwell) ISBN 0-631-15624-0.

- de’Este, Sorita. Circle for Hekate: volume 1. 1910191078

- Farnell, Lewis Richard, (1896). "Hekate: Representations in Art", The Cults of the Greek States. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Fowler, R. L. (2000), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 1: Text and Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0198147404.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Green, C. M. C., Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, Cambridge University Press, University of Iowa, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-85158-9. Online text available at Google books.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles, (1990). Hekate Soteira: A Study of Hekate's Role in the Chaldean Oracles and Related Literature.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles, (1991). Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. ISBN 0-520-21707-1

- Kerenyi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks. 1951.

- Kern, Otto. Orphicorum Fragmenta, Berlin, 1922. Internet Archive

- Mallarmé, Stéphane, (1880). Les Dieux Antiques, nouvelle mythologie illustrée.

- Merriam-Webster (1995). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Inc, Merriam-Webster. ISBN 9780877790426..