Seeress (Germanic)

In Germanic paganism, a seeress is a woman said to have the ability to foretell future events and perform sorcery. They are also referred to with many other names meaning "prophetess", "staff bearer", "wise woman" and "sorceress", and they are frequently called witches or priestesses both in early sources and in modern scholarship.

They were an expression of the pre-Christian shamanic traditions of Europe, and they held an authoritative position in Germanic society. Mentions of Germanic seeresses occur as early as the Roman era, when, for example, they at times led armed resistance against Roman rule and acted as envoys to Rome. After the Roman Era, seeresses occur in records among the North Germanic people, where they form a reoccurring motif in Norse mythology. Both the classical and the Norse accounts imply that they used wands, and describe them as sitting on raised platforms during séances.

Ancient Roman and Greek literature records the name of several Germanic seeresses, including Albruna, Veleda, Ganna, and, by way of an archaeological find, Waluburg. Norse mythology mentions several seeresses, some of them by name, including Heimlaug völva, Þorbjörg lítilvölva, Þordís spákona, and Þuríðr Sundafyllir. In North Germanic religion, the goddess Freyja has a particular association with seeresses, and there are indications that the Viking princess and Russian saint, Olga of Kiev, was one such, serving as a "priestess of Freyja" among the Scandinavian elite in Kievan Rus' before they converted to Christianity.

Archaeologists have identified several graves that appear to be the remains of Scandinavian seeresses. These graves contain objects such as wands, seeds with hallucinogenic and aphrodisiac properties, and a variety of items indicating high status.

Societal beliefs about the practices and abilities of seeresses would contribute to the development of the European concept of "witches", because their practices survived Christianization, although the practitioners became marginalized, and evolved into north European mediaeval witchcraft. Germanic seeresses are mentioned in popular culture in a variety of contexts. In Germanic Heathenry, a modern practice of Germanic pagan religion, seeresses once again play a role.

Names and terminology

Aside from the names of individuals, Roman era accounts do not contain information about how the early Germanic peoples referred to them, but sixth century Goth scholar Jordanes reported in his Getica that the early Goths had called their seeresses haliurunnae (Goth-Latin).[1] The word also appears in Old English (OE), hellerune ("seeress" or "witch") and in Old High German (OHG) as hellirûna ("necromancy") and hellirunari ("necromancer"),[2][3] and from these forms an earlier Proto-Germanic form *χalja-rūnō(n) has been reconstructed,[4] in which the first element is *χaljō, i.e. Hel, the abode of the dead,[5] and the second is *rūnō ("mystery, secret").[6] At this time the word *rūnō still referred to chanting and not to letters (rune),[3] and in the sense "incantation" it was probably borrowed from Proto-Germanic into Finnish where runo means "poem".[7]

In OE, hellerune ("seeress" or "witch"), or helrūne, has the synonym hægtesse,[8] a term that is also found in Old Dutch, haghetisse ("witch")[9] and in OHG hagazussa,[10] hagzussa or hagzissa.[11] These West Germanic forms are probably derived from a Proto-Germanic word with positive connotations, *χaʒaz, from which are also derived Old Norse (ON) hagr ("skillful") and Middle Hight German (MHG) be-hac ("of pleasure").[9] However, it is sometimes proposed that the first element is a term corresponding to Swedish hage ("wooded paddock") in the sense of "fence",[12] i.e. PGmc *χaʒōn ("pasture", "enclosure"), from whence also English hedge (through *χaʒjaz).[13] In that case it would be etymologically related to ON túnriða and OHG zûnrite ("fence rider"), where tún/zûn does not refer to an enclosure but metonymically to the fence surrounding it.[12] In the Westrogothic law , it was a punishable offence to accuse a woman of having ridden a fence-gate, in the appearance (hamr) of a troll.[14] Kluge reconstructs the PGmc form as *haga-tusjō, where the last element *tusjō could mean "spirit", from PIE *dhwes-.[11]

The various names in North Germanic sources may give the impression that there were two types of sorceress, the staff-bearers, or seeresses (vǫlva), and the women who were named for performing magic (seiðkona). However, there is little that the scholar could use to differentiate them, if such a distinction ever existed, and the two types of names are often used synonymously and about the same women.[15]

The term vǫlva means "staff bearer" and is related etymologically to the names of the early Germanic seeresses Ganna, Gambara and Waluburg. The use of wands in divination and clairvoyance appears to have lived on from the classical era into the Viking Age. The name vǫlva and derivations of the name appear 23 times in the sources, and seiðkona ("seiðr woman/wife") appears eight times; the two terms are often used interchangeably.[15] The second most common term is spákona ("prophecy woman/wife") with the variants spákerling ("old prophecy woman") and spámey ("prophecy maiden"), which appears 22 times, again interchangeably with vǫlva and seiðkona to refer to the same woman.[16] There is also the name vísendakona ("wise woman" or "knowing woman"), which appears eight times in the sources. Þorbiorg in Eiríks saga rauða is called both a vísendakona, vǫlva and a spákona. It is possible that the names once had different meanings, but at the time of the saga's composition, they were no longer distinguished in meaning, just as the words sorceress and witch are interchangeable in modern popular language. There are also five instances of a group of rarer names having the element galdr ("incantation"), with the names galdrakonur ("galdr women"), galdrakerling ("old galdr woman") and galdrasnót ("galdr lady"). In addition there is the word galdrakind ("galdr creature") with negative connotations.[17]

There is also the reconstructed word *vitka which may be connected to the Wecha in Gesta Danorum, book III and refer to a kind of sorceress. It seems to be the feminine form of vitki ("sorcerer"), and it is only attested from Lokasenna 24, where Loki accuses Odin of having travelled around the world vitka líki (in the "guise of a vitka").[17]

The personal name Heiðr appears 66 times as a word for sorceress in the prose sources. It appears twice in the Poetic Edda, in Hyndluljóð and in Vǫluspá, where it is a name assumed by Gullveig in connection with the War of the Gods. In a study by McKinnell of Norse sagas and Landnámabók, there is only one instance of a woman named Heiðr who does not act as a seeress. The name has been connected to heath and heathen, but it has also been explained with meanings that connote "radiance and golden light, honour and payment".[18]

Lastly, there is the term fjolkyngiskona that only meant "sorceress", and a number of derogatory names that correspond to "witch" with many negative connotations, and these terms include skass ("ogress"[19]), flagð(kona) ("ogress"[20]), gýgr ("ogress"[21]), fála ("Giantess"[22]), hála and fordæða ("evil doer"[23]).[18]

The term shamanism

There has long been an academic debate on whether the seeresses' practice should be regarded as shamanism. However, this does not pertain to the concept of shamanism in a wider definition (see e.g. the definitions of the OED), but rather to what degree similarities can be found between what is preserved about them in Old Norse literature and the shamanism of northern Eurasia in a more restricted sense. The majority of scholars support the "shamanic interpretation, and the presence of ecstatic rituals" (e.g. Ellis Davidson, Ohlmarks, Pálsson, Meulengracht Sørensen, Turville-Petre and de Vries), while a minority is sceptic (e.g. Bugge, Dillmann, Dumézil, Näsström and Schjødt), but there are divergent opinions within the two camps.[24] Clive Tolley, who is among the sceptics, writes that if shamanism is defined as "tundra shamanism" as represented by the Sámi of Scandinavia and as defined by Edward Vajda, then the differences are too great. He allies himself with the position of Ohlmarks, who was familiar with a wide range shamanism and rejected it in 1939, in a debate with Dag Strömbäck who found similarities with Sámi practices. However, Tolley concedes that if shamanism is defined in line with the words of Åke Hultkrantz (1993) as "[...] direct contact with spiritual beings and guardian spirits, together with the mediating role played by a shaman in a ritual setting [...] The presence of guardian spirits during the trance and following shamanic actions [...]" then it is correct to define their practices as "broadly shamanic". However, he considers that in this case shamanism also includes traditional practices from a large part of Europe, such as the witchcraft of medieval Europe and the practices of ancient Greece.[25] An opposing view is held by Neil Price, who has studied circumpolar shamanism, and argues that he finds enough similarities to define the North Germanic seeresses as shamans also in the stricter sense.[26]

Role in society

Fate is central in Germanic literature and mythology, and men's destiny is extricably linked to supernatural women and seeresses. Morris comments that the importance of fate can not be overstressed, and the seeresses were feared and revered by gods and mortals alike. Even the god Odin himself consulted them. The Norns are an example of the link between women and fate, which was elevated in Germanic society, and the association was incarnated by the seeresses.[27]

The political role that the seeresses played was always present when the Romans were dealing with the Germanic tribes, and the Romans had to take their opinion into account.[28] Ganna's political influence was so considerable that she was taken to Rome together with Masyos, the king of her tribe, where they had an audience with the Roman emperor Domitian and were treated with honours, after which they returned home.[29][30] The Roman historian Tacitus, who appears to have met Ganna and to have been informed by her of most of what we know of early Germanic religion,[31] wrote:

... they believe that there resides in women an element of holiness and a gift of prophecy ...[27]

Another telling account by Tacitus about their power was a statement by the Batavian tribe to the Romans:

... and if we must choose between masters, then we may more honorably bear with the Emperors of Rome, than with the women of the German[ic]s.[27]

However, the seeresses do not appear to have been just any women, but were those who occupied a special office.[32] Both Mogk and Sundqvist have commented that although the seeresses were referred to as "priestesses" by the Romans, they probably should not be so labelled in a strict sense.[33] As for the later North Germanic version, Näsström writes that the völva did not perform any sacrifices, but her roles as a prophetess and as a sorceress were still important aspects of the spiritual life of her society.[34] Price comments that Katherine Morris has usefully defined these women:

[...] magic was manipulative, practical, and achieved immediately. The sorceress changed the weather, cast spells, or controlled things outside of herself.[35][36]

Attestations

Germanic seeresses are first described by the Romans, who discuss the role seeresses played in Germanic society. A gap in the historical record occurs until the North Germanic record began over a millennium later, when the Old Norse sagas frequently mention seeresses among the North Germanic peoples. It is noteworthy that Veleda, who prophesied in a high tower in the first century, finds an echo in the thirteenth-century account of Þorbjörg lítilvölva who prophesied from a raised platform in Eiríks saga rauða.[37] Simek comments that the saga's account of Þorbjörg's raised platform and her wand conveys authentic practices from Germanic paganism.[38]

Roman Era

In his ethnography of the ancient Germanic peoples, Germania, Tacitus expounds on some of these points. In chapter eight, he reports the following about women in then-contemporary Germanic society and the role of seeresses:

- A. R. Birley translation (1999):

- It is recorded that some armies that were already wavering and on the point of collapse have been rallied by women pleading steadfastly, blocking their path with bared breasts, and reminding their men how near they themselves are to being taken captive. This they fear by a long way more desperately for their women than for themselves. Indeed, peoples who are ordered to include girls of noble family among their hostages are thereby placed under a more effective restraint. They even believe that there is something holy and an element of the prophetic in women, hence they neither scorn their advice nor ignore their predictions. Under the Deified Vespasian we witnessed how Veleda was long regarded by many of them as a divine being; and in former times, too, they revered Albruna and a number of other women, not through servile flattery nor as if they had to make goddesses out of them.[39]

Writing also in the first century AD, Greek geographer and historian Strabo records the following about the Cimbri, a Germanic people, in chapter 2.3 of volume seven of his encyclopedia Geographica:

- Horace Leonard Jones translation (1924):

- Writers report a custom of the Cimbri to this effect: Their wives, who would accompany them on their expeditions, were attended by priestesses who were seers; these were grey-haired, clad in white, with flaxen cloaks fastened on with clasps, girt with girdles of bronze, and bare-footed; now sword in hand these priestesses would meet with the prisoners of war throughout the camp, and having first crowned them with wreaths would lead them to a brazen vessel of about twenty amphorae; and they had a raised platform which the priestess would mount, and then, bending over the kettle, would cut the throat of each prisoner after he had been lifted up; and from the blood that poured forth into the vessel some of the priestesses would draw a prophecy, while still others would split open the body and from an inspection of the entrails would utter a prophecy of victory for their own people; and during the battles they would beat on the hides that were stretched over the wicker-bodies of the wagons and in this way produce an unearthly noise.[40]

Writing in the second century CE, Roman historian Cassius Dio describes in chapter 50 of his Roman History an encounter between Nero Claudius Drusus and a woman with supernatural abilities among the Cherusci, a Germanic people. According to Diorites Cassius, the woman foresees Drusus's death, and he dies soon thereafter:

- Herbert Baldwin Foster and Earnest Cary translation (1917):

- The events related happened in the consulship of Iullus Antonius and Fabius Maximus. In the following year Drusus became consul with Titus Crispinus, and omens occurred that were anything but favourable to him. Many buildings were destroyed by storm and by thunderbolts, among them any temples; even that of Jupiter Capitolinus and the gods worshipped with him was injured. Drusus, however, paid no heed to any of these things, but invaded the country of the Chatti and advanced as far as that of the Suebi, conquering with difficulty the territory traversed and defeating the forces that attacked him only after considerable bloodshed. From there he proceeded to the country of the Cherusci, and crossing the Visurgis, advanced as far as the Albis, pillaging everything on his way.

- The Albis rises in the Vandalic Mountains, and empties, a mighty river, into the northern ocean. Drusus undertook to cross this river, but failing in the attempt, set up trophies and withdrew. For a woman of superhuman size met him and said: "Whither, pray, art thou hastening, insatiable Drusus? It is not fated that thou shalt look upon all these lands. But depart; for the end alike of thy labours and of thy life is already at hand".

- It is indeed marvellous that such a voice should have come to any man from the Deity, yet I cannot discredit the tale; for Drusus immediately departed, and as he was returning in haste, died on the way of some disease before reaching the Rhine. And I find confirmation of the story in these incidents: wolves were prowling about the camp and howling just before his death; two youths were seen riding through the midst of the camp; a sound as of women lamenting was heard; and there were shooting stars in the sky. So much for these events.[41]

Veleda

In the first and second centuries CE, Greek and Roman authors—such as Greek historian Strabo, Roman senator Tacitus, and Roman historian Cassius Dio—wrote about the ancient Germanic peoples, and made note of the role of seeresses in Germanic society. Tacitus mentions Germanic seeresses in book 4 of his first century CE Histories.

- The legionary commander Munius Lupercus was sent along with other presents to Veleda, an unmarried woman who enjoyed wide influence over the tribe of the Bructeri. The Germans traditionally regard many of the female sex as prophetic, and indeed, by an excess of superstition, as divine. This was a case in point. Veleda's prestige stood high, for she had foretold the German successes and the extermination of the legions. But Lupercus was put to death before he reached her.[42]

Ganna

A seeress named Ganna is mentioned by the Roman historiographer Cassius Dio in the early 3rd century. The context is the campaign east of the Rhine by Emperor Domitian in the 80s of the 1st century CE. Ganna belonged to a tribe called the Semnones who were settled east of the river Elbe, and she appears to have been active in the second half of the 1st century, after Veleda's time.[29] Ganna's political influence was considerable enough that she was taken to Rome together with Masyos, the king of her tribe, where they had an audience with the Roman emperor and were treated with honours, after which they returned home.[29][30] This probably happened in 86 AD, the year after his final war with the Chatti, when he made a treaty with the Cherusci, who were settled between the rivers Weser and the Elbe.[29]

During their stay in Rome, Ganna and Masyos appear also to have met with the Roman historian Tacitus who reports that he discussed the Semnoni religious practices with informants from that tribe, who considered themselves the noblest of the Suebi. Bruce Lincoln (1986) discusses Tacitus' meeting with Ganna and what the Roman historian learnt of the mythological traditions of the early Germanic tribes, and of the Semnoni's ancestral relationships with the other tribes from Ing (Yngvi), Ist and Irmin (Odin), the sons of Mannus, the son of Tuisto. The Semnoni reenacted the "horrific origins" of their nation with a human sacrifice, with each victim representing Tuisto (the "twin") and being cut up to repeat the "acts of creation", which can be compared to how Odin and his brothers cut up the body of the primordial giant Ymir (the "twin"[43]) to form the world in Norse mythology.[44] Rudolf Simek notes that Tacitus also learnt that the Semnoni performed their rites at a holy grove that was the cradle of the tribe's inception, and that could only be entered when they were fettered. The god who was worshiped was probably Odin, and being fettered may have been an imitation of Odin's self-sacrifice. This grove has for a long time been identified with the Grove of Fetters, where the hero was sacrificed to Odin in the Eddic poem, Helgakviða Hundingsbana II.[45]

It is notable that Ganna is not referred to as a sibylla, but as a theiázousa in Greek, which means "someone making prophesies".[29] Her name Ganna is usually interpreted as Proto-Germanic Gan-no and compared with Old Norse gandr in the meaning "magical staff" (for the meanings of gan- and gandr, see the section on magical Projection); Ganna would mean the "one who carries the magical staff" or "she who controls the magical staff or something similar". Her name is thus grouped with other seeresses with staff names, like Gambara ("wand-bearer") and Waluburg from walu-, "staff" (ON vǫlr), and the same word is found in the name of North Germanic seeresses, the vǫlur.[46] Simek analyses gandr as a "magic staff" and the "insignia of her calling", but in a later work he adds that it meant "magic object or being" and instead of referring to a wand as her tool or insignia, her name may instead have been a reference to her function among the Germanic tribes (like Veleda's name).[29] Sundqvist suggests that the name may have referred instead to her abilities,[47] like de Vries who connects her name directly to the ablaut grade ginn- ("magical ability"),[48] also treated further down in the section on magical Projection.

Waluburg

Dating from the second century CE, an ostracon with a Greek inscription reading Waluburg. Se[m]noni Sibylla (Greek 'Waluburg, sibyl from the Semnones') was discovered in the early twentieth century on Elephantine, an Egyptian island. The name occurs among a list of Roman and Graeco-Egyptian soldier names, perhaps indicating its use as a payroll.[49]

The first element *Walu- is probably Proto-Germanic *waluz 'staff', which could be a reference to the seeresses' insignia, the magic staff, and which connects her name semantically to that of her fellow tribeswoman, the seeress Ganna,[28] who probably taught her the craft[50] and who had an audience with emperor Domitian in Rome.[29][30] In the same way, her name may also be connected to the name of another Germanic seeress, Gambara, which can be interpreted as 'staff bearer' (*gand-bera[47] or *gand-bara[51]), see gandr. The staffs are also reflected in the North Germanic word for seeress, vǫlva 'staff bearer'.[52][46][36] In North Germanic accounts, the seeresses were always equipped with a staff, a vǫlr,[53] from the same Proto-Germanic root *waluz.[54]

Schubart proposes that she may have been a war prisoner accompanying a Roman soldier in his career that led to him being stationed in Egypt at the first cataract.[55] Simek considers her to have been deported by the Roman authorities, and he writes that it is uncertain how she arrived at Elephantine, but it is not surprising considering the significant and obvious influence that the Germanic seeresses wielded politically.[56] Clement of Alexandria who lived in Egypt at the same time as Waluburg, and the earlier Plutarch, mentioned that the Germanic seeresses also could predict the future while studying the eddies, the whirling and the splashing of currents,[53] and Schubart suggests that this is the reason why Waluburg found herself at the swirling waters of the First Cataract of the Nile.[55]

Gambara

The Origo Gentis Langobardorum (Origin of the Lombard/Langobard people), a seventh-century Latin account, and the Historia Langobardorum (History of the Lombard/Langobards), from the 8th c., relate the legend that before, or after, the Langobard people, then known as the Winnili, emigrated from Scandinavia, led by the brothers Ibor and Agio, their neighbours, the Vandals, demanded that they pay tribute, but their mother Gambara advised them not to. Before the battle, the Vandals called on Odin (Godan[57]) to give them victory, but Gambara invoked Odin's wife Frigg (Frea) instead.[58] Frigg advised them to trick Odin, by having the Winnili women spread their hair in front of their faces so as to look bearded and stand before the window from which Odin looked down on Earth.[59] Odin was embarrassed and asked who the "long-beards" (longobarbae[57]) were, and thus naming them he became their godfather and had to grant them victory.[60]

Gambara is called phitonissa in Latin which means "priestess" or "sorceress", and in the Chronicum Gothanum, she is also specifically called sibylla, i.e. "seeress".[60] Pohl comments that Gambara lived in a world and era where prophecy was important, and not being a virgin like Veleda, she combined the roles of priestess, wise woman, mother and queen.[61] Her name may mean "wand-bearer" (*gand-bera[47] or *gand-bara[51]) with the same meaning as Old Norse vǫlva,[60][51] while the name of her son Ibor means "boar", the animal sacred to the Norse god Freyr, the god of fertility and the main god of the Vanir clan of the gods.[60] Hauck argues that the legend goes back to a time when the early Lombards primarily worshiped the mother goddess Freyja, as part of the Scandinavian Vanir worship,[62][63] and he adds that a Lombard counterpart of Uppsala has been discovered in Žuráň, near Brno in the modern day Czech republic.[64]

In Lombard, Odin and Frigg were called Godan and Frea, while they were called Uodan and Friia in Old High German and Woden and Frig in Old English.[65] The window from which Odin looked down on earth recalls the Hliðskjálf of Norse mythology,[60] from where he could see everything,[66] and where Frigg also conspires against Odin in the poem Grímnismál, in a parallel with the Lombard myth.[67][68][69] Frigg's infidelity and connection with prophecy normally belong to Freyja, and her association with magic (seiðr), but there are many similarities between them,[70] and Freyja and Frigg may originally have been the same goddess.[70][71] Scholars may identify Frea as Frigg/Freyja,[72] or simply as Freyja.[73]

Haliurunas

Getica, a 6th century work on the history of the Goths, reports that the early Goths had called their seeresses haliurunas (or haliurunnae, etc.) (Goth-Latin).[1] They were in the words of Wolfram "women who enganged in magic with the world of the dead", and they were banished from their tribe by Filimer who was the last pre-Amal dynasty king of the migrating Goths.[74] They found refuge in the wilderness where they were impregnated by unclean spirits from the Steppe, and engendered the Huns, which Pohl compares with the origin of the Sarmatians as presented by Herodotus.[75] The account serves as an explanation for the origins of the Huns.[76]

The account may be based on a historic event when Filimer banished his seeresses as scapegoats for a defeat when their prophesy had proved wrong,[77] They may also have represented the conservative faction and resisted change. This change may have been the rise of the Amal clan and their claims of ancestry from the anses (the Aesir clan of gods). As in the case of the early Lombards, this would have taken place after a decisive victory that saved a tribe whose existence had been threatened by enemies. Odin was still a new god, and the Goths worshiped instead the "old" god Gaut who was made the Scandinavian great-grandfather of Amal, the founder of the new ruling clan.[78]

Wagner argues that the demonization of both the women and the Huns shows that the account was written in a Christian context.[79] Morris (1991) comments that it was a precedent for future Christian tradition, where demonic women have intercourse with the Devil or with demons. In the Anglo-Saxon Leechbook from the 10th century, there is a prescription for a salve against "women with whom the Devil has sexual intercourse," and in the 11th century, there appeared the idea that witches and heretics had sexual orgies during their meetings at night.[80]

North Germanic corpus

Few records of myths among the Germanic peoples survive to modern times. The North Germanic record is an exception, containing the vast majority of material that survives about the mythology of the Germanic peoples. These sources mention numerous seeresses among the North Germanic peoples, including the following:

| Seeress name (Old Norse) | Attestations | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Heimlaug völva | Gull-Þóris saga | In Gull-Þóris saga, Heimlaug assists the saga protagonist by way of prophecy. |

| Heiðr | Hrólfs saga kraka, Landnámabók, Örvar-Odds saga | Various seeresses by the name of Heiðr occur in the Old Norse corpus, including Gullveig, who scholars generally consider to be another name for the goddess Freyja |

| Þorbjörg lítilvölva | Eiríks saga rauða | In Eiríks saga rauða, Þorbjörg lítilvölva travels to Scandinavian farms in Greenland and predicts the future. |

| Þordís spákona | Vatnsdæla saga, Kormáks saga | Tenth century Icelandic seeress and regional leader[81] |

| Þoríðr spákona | Landnámabók | |

| Þuríðr sundafyllir | Landnámabók | |

| Unnamed seeresses | Völuspá, Völuspá hin skamma | Unnamed seeresses occur in various contexts in the Old Norse corpus. For example, as its name implies, the poem Völuspá ('the foretelling of the seeress') consists of an undead seeress reciting information about the past and future to the god Odin.[82] |

Eiríks saga rauða provides a particularly detailed account of the appearance and activities of a seeress. For example, regarding the seeress Þorbjörg Lítilvölva:

A high seat was set for her, complete with a cushion. This was to be stuffed with chicken feathers.

When she arrived one evening, along with the man who had been sent to fetch her, she was wearing a black mantle with a strap, which was adorned with precious stones right down to the hem. About her neck she wore a string of glass beads and on her head a hood of black lambskin lined with white catskin. She bore a staff with a knob at the top, adorned with brass set with stones on top. About her waist she had a linked charm belt with a large purse. In it she kept the charms which she needed for her predictions. She wore calfskin boots lined with fur, with long, sturdy laces and large pewter knobs on the ends. On her hands she wore gloves of catskin, white and lined with fur.

When she entered, everyone was supposed to offer her respectful greetings, and she responded by according to how the person appealed to her. Farmer Thorkel took the wise woman by the hand and led her to the seat which had been prepared for her. He then asked her to survey his flock, servants and buildings. She had little to say about all of it.

That evening tables were set up and food prepared for the seeress. A porridge of kid’s milk was made for her and as meat she was given the hearts of all the animals available there. She had a spoon of brass and a knife with an ivory shaft, its two halves clasped with bronze bands, and the point of which had broken off.[83]

Olga of Kiev

There are indications that the Viking princess and Russian saint Olga of Kiev may have served as a Völva, and as a "priestess of Freyja", before converting to Christianity.[72] In the Primary Chronicle, she is described by the noblemen as the "wisest of all women", where wise has several meanings and her reputation as being wise goes back to her pre-conversion years.[84] Her wisdom is also reported by Óláfs saga Tryggvassonar, where she is called Allogia and mistaken for Vladimir the Great's old mother, although she was his grand-mother. There she is described as "very wise" and her main function at the court was as a prophetess, one whose predictions also came true. When the king of Kievan Rus' celebrated Yule, he asked her to predict the future and to do so she was carried to him on a chair which recalls the elevated platforms of the seeresses. Although he may not have a transmitted a historical event, Oddr Snorrason, who wrote the saga in the 12th c., clearly identified Olga as a völva.[85]

Olga is strongly associated with birds in the sources,[86] which also was true of the goddess Freyja, the goddess of magic (seiðr).[87] The goddess was popular among Scandinavian women in general, and especially among aristocratic women who profited from corollary authority and power. Older scholarship believed that the aristocratic Norse women passively waited at home for their husbands, but the modern view is that they actively took part in warfare from home with seiðr, a magic reflected in the Norse poem Darraðarljóð.[88][72] Consequently, Olga may have been regarded as a high priestess of Freyja, a status which would not only have appealed to her Scandinavian kinsmen but also to her Slavic subjects who would have identified Freyja with the Slavic goddess Mokosh, who was represented as the only goddess among the six raised idols in Kiev.[89]

In 2008, a Scandinavian chamber grave called N°6 was excavated in Pskov, where Olga was born. It was a syncretic grave containing elements from Norse paganism and from Christianity; it has been dated to c. 960. It contained an object called a jartegn, a token given to officials by Scandinavian kings and Rus' rulers, indicating that the buried man had political influence.[90] On the front side it has a bident, which later evolved into a trident and was a symbol of the Rurik dynasty. Above the bident there is a key, and keys were a symbol of the Scandinavian mistress, as Scandinavian women carried the keys of the homestead; Kovalev (2012) argues that the key was also a symbol of Freyja.[91] According to Kovalev, during her regency, before Sviatoslav I came of age, Olga may have chosen to add the key to the seal of the ruler of Kievan Rus', the key being a symbol whose significance would have been understood all over northern Europe, not only as the symbol of a woman who has authority, but also as a symbol of guardianship.[92] On the reverse side the jartegn has the image of a falcon, a bird not only associated with the Swedish and Rus' elite of the Viking Age, but also especially associated with the goddesses Freyja and Frigg, who can transform themselves into falcons.[93]). The falcon also appears to wear a cloak of the type worn by Scandinavian women.[94] There is a cross above the falcon; coins bearing the falcon and the cross are dated to Olga's time in the 950s and the 960s.[95] Images of women with a bird's head have also been found on the Norwegian 9th c. Oseberg tapestry fragments,[96] and the women have been identified as priestesses of Freyja wearing bird masks.[97] Several scholars consider the woman who was buried with the tapestry to have been a völva.[98]

Archaeological Record

The archaeological record for Viking Age society features a variety of graves that are identified as those of North Germanic seeresses. A notable example occurs at Fyrkat, in the northern Jutland region of Denmark. Fyrkat is the site of a former Viking Age ring fortress; the cemetery section of the site contains, among about 30 others, the grave of a woman buried within a horse-drawn carriage and wearing a red and blue dress embroidered with gold thread, all signs of high status. While the grave contains items commonly found in female Viking Age graves such as scissors and spindle whorls, it also contains a variety of other rare and exotic items. For example, the woman wore silver toe rings (otherwise unknown in the Scandinavian record) and her burial contained two bronze bowls originating from Central Asia.[99]

The grave also contained a small purse with seeds from henbane, a poisonous plant, inside it, and a partially disintegrated metal wand, used by seeresses in the Old Norse record. According to the National Museum of Denmark:

- If these seeds are thrown onto a fire, a mildly hallucinogenic smoke is produced. Taken in the right quantities, they can produce hallucinations and euphoric states. Henbane was often used by the witches of later periods. It could be used as a "witch's salve" to produce a psychedelic effect, if the magic practitioners rubbed it into their skin. Did the woman from Fyrkat do this? In her belt buckle was white lead, which was sometimes used as an ingredient in skin ointment.[99]

Henbane's aphrodisiac properties may have also been relevant to its use by the seeress.[100] At the feet of the corpse was a small box, called a box brooch and originating from the Swedish island of Gotland, which contained owl pellets and bird bones. The grave also contained amulets shaped like a chair, potentially a reflection of the long-standing association of seeresses and chairs (as described in Strabo's Geographica from the first century CE, discussed above).[99]

A ship setting grave in Köpingsvik, a location on the Swedish island of Öland, also appears to have contained a seeress. The woman was buried wrapped in bear fur with a variety of notable grave goods: the grave contained a bronze-ornamented staff with a small house atop it, a jug made in Central Asia, and a bronze cauldron smithed in Western Europe. The grave contained animals and humans, perhaps sacrificed.[100]

The Oseberg ship burial also may have contained a seeress. The ship contained the remains of two people, one a woman of elevated status and the other possibly a slave. Along with a variety of other objects, the grave contained a purse containing cannabis seeds and a wooden wand.[100]

Another notable grave containing what has been identified as the remains of a seeress was excavated by archaeologists in Hagebyhöga in Östergötland, Sweden. The grave contained female human remains interred with an iron wand or staff, a carriage, horses, and Arabic bronze jugs. The grave also contained a small silver figurine of a woman with a large necklace, which has been interpreted by archaeologists as representing the goddess Freyja, a deity strongly associated with seiðr, death, and sex.[100]

Activities

In Scandinavian sources, seeresses work as diviners using a practice called seiðr on a ritual platform called seiðhjallr (see below), which is associated with shamanism. They also take part in other activities, but they do not appear to perform sacrifices. They are described as ritual specialists travelling from settlement to settlement, sometimes with a group of followers, and late sources tell that they received payment for their services.[101]

Chanting

In the Roman era, the Germanic word for chanting was similar to the reconstructed Proto-Germanic form *ʒalđran, which later evolved into Old Norse galdr ("song, charm; witchcraft, sorcery"), OHG galtar ("incantation, charm") and Old English ʒealdor with the same meaning,[102] also rendered as galdor ("sound, song, incantation, spell, enchantment").[103] It is derived from *ʒalanan, which became ON gala ("to crow, sing"), OHG galan ("to incantate") and OE ʒalan ("to sing").[104] It is related to the English nightingale and yell, to Latin gallus ("cock") and it appears in ON gylfra ("witch").[103] The many uses of chanting are revealed in the words that are derived from galdr, such as galdrabók ("book of magic"), galdrasmiðja ("objects used for magic"), galdravél ("a magic device"), galdrahríð ("magic storm"), galdrastafir ("magical characters") and valgaldr (a kind of Odinic necromancy).[105] The modern Swedish word galen ("crazy", literally "having been chanted") is derived from the word for this practice.[106]

Other names for the songs are varðlok(k)ur and seiðlæti, where the latter simply means "seiðr songs". The former term is more complex, and scholars such as Cleasby and Vigfússon, Tolley, Strömbäck and Price have derived it from vǫrðr ("guard, protector").[107][108][109][110] Several scholars have also compared it to the Scotting dialect word warlock,[110] and scholars such as Cleasby, Vigfússon and Strömbäck consider it to be the origin of the Scottish word.[111][108] Katherine Morris translates the word as "warlock-song".[112]

In Eiríks saga rauða, the songs are said to be sung or spoken by the seeresses' followers, but at the same time there is only one woman who knows them and sings them. Price argues that since the name appears with two spellings (depending on the manuscript), it is possible to interpret the name in two ways, either by referring to loka ("fastening") or lokka ("lure"). He interprets the spelling varðlokkur as meaning "to lure the spirits", and varðlokur as meaning "locking the spirits under the seeress' power". In this way the term can be simultaneously interpreted as attracting the spirits and locking them under the summoner's power, and probably also securing them as protection against hostile entities. In the poem Grógaldr, urðarlokkur, the norn of fate Urðr's lokkur, are said to protect a person on all sides, and they are also likely bound to that individual.[110] Tolley points out that the form urðarlok(k)ur for these protective spells is probably a reinterperation of an older vǫrðlokur ("ward spells"), or more likely another possible form with the same meaning, varðarlokur ("spells of warding").[113]

The chants appear to have been sung with a high pitch, and they are reported to have been pleasing to the ear. In the Laxdœla saga, the sweetness of a chant (seiðlæti) lures a boy to his death, as intended, and a pleasing sound would also have been understood as attracting spirits to the summoner. Price suggests that the nearest equivalent to these high pitched and pleasing chants are the traditional Swedish herding calls (lockrop in modern Swedish, which still contains the linguistic element lokk-).[110]

Projection

.JPG.webp)

While the varðlok(k)ur (mentioned above) attracted protective spirits that provided information to the enchantress, there were animal spirits that were sent out to collect information for her, and to perform other tasks.[114] Consequently, the task of the sorceress was to control spirits,[115] and the name that appears to have been used for these spirits and for several other aspects in sorcery is gandr (pl. gandir); the relationship between the extended meanings of gandr is complex and a matter of discussion among scholars.[116][117] The original meaning appears to be "something which is connected with the soul of the magician and can be sent out from him or her in sleep or extasy".[117]

According to de Vries, the origin of gandr is a word gan- meaning "magic", of which there was an ablaut grade gin- (in English there is still a semantic relationship between the ablaut grades swam and swim, and sat and sit) that may be found in the name of the primordial chasm Ginnungagap[118] ("space filled with magic powers"),[119] and on the migration age Björketorp and Stentoften runestones, it appears in the sense "magically powerful" in Proto-Norse ginnarunaʀ ("powerful runes").[120] It was also used as an intensifier in the compounds ginnregin ("great powers", i.e. the gods) and ginnheilagr ("extremely holy").[119] As a noun it meant "falsehood" and "deception",[119] while the verb ginna meant "to dupe or to fool someone".[121]

The gan- ablaut grade was combined with the suffix -đra-, the same as in galdr, from gala, "chant" (see section on Chanting, above). Tolley argues that the original meaning cannot have included "staff", but rather that it would have meant "sorcerer spirit" from which would have been derived the additional meanings "wand", "wolf" and "serpent" (Jörmungandr). The "sorcerer's spirit" (gandr) could be summoned or sent out to gather information; this spirit is in animal form, but possibly not always.[118] The extension to the meanings "wolf" and "serpent" is due to the fact that spirits had animal form, and the term gandreið originally meant the ride of a sorcerer on a spirit in animal form such as that of a wolf. Supernatural creatures could also use wolves as steeds; later the term came to refer to the sorcerer riding on a staff.[122]

In Old Norse sources, the noun gandreið and the verb renna gand (or renna gǫndum) can refer to going out to gather information in a non-corporeal sense, but it can also refer to magically flying on a staff in a physical sense.[123] Price disagrees with Tolley's argument that "staff" was not part of the original meaning of gandr and suggests that the staff/wand (gandr or gǫndull) was part of the ritual of summoning and releasing the gandir ("spirits") for the purpose of clairvoyance or prophesy, and sometimes in order to harm people. The use of the staff may have implied sexual magic and sexual acts while it was used, and the staff was possibly also ridden in order to hurt enemies.[124]

Some examples of aggressive projection are also preserved in Old English poems, such as the "Nine Herbs Charm", "Against a Dwarf" and "Wið færstice". Especially the last poem contains many Germanic pagan elements that are also found in Old Norse sources, such as sorceresses (hægtessan), elves (ylfa), Æsir gods (esa), the magic of smiths, and the presence of women that are like Valkyries.[125]

During the eighth decade of the first century, the Semnonian seeress Ganna succeeded the Bructerian seeress Veleda as the leader of an alliance of Germanic tribes when the latter had been captured and deported by the Romans. Her name "Ganna" is usually linked to the ON word gandr – Simek comments that instead of being a reference to a wand as her tool or insignia, her name may be a reference to her function among the Germanic tribes (like Veleda's name).[29] Sundqvist also comments that the name may have referred instead to her abilities,[47] like de Vries who connects her name directly to the grade gin(n)- (see above).[48]

Prophesying

There are two ways in which the seeress conveys the acquired information to the audience. One of them is by having a seizure during the trance and gasping for air with a wide open mouth (Hrólfs saga kraka and Hauks þáttr hábrókar). She delivers her prophesy during the trance, and it may be said that a song appears from elsewhere in her mouth (Ǫrvar-Odds saga and Hrólfs saga kraka).[126] In Hrólfs saga kraka, it is in the beginning of the trance that she breathes in, and Tolley considers that this may represent a breathing in of spirits rather than her letting out her soul.[127] Price comments that as far as textual criticism is concerned, this detail can not have been borrowed from those of the neighbouring Fenno-Ugric peoples, because the closest practitioners are the Yukaghir people on the other side of Eurasia, whose practices were inaccessible for the saga writers.[128]

The other situation occurs when the seeress has returned from her trance and tells about it while awake (Eiríks saga rauða and Vatnsdœla saga).[126]

Attributes

Platforms

There appears to be a continuity between elements such as the first century Bructerian seeress Veleda's tower and the seiðhjallr that played an important role in Scandinavian sources.[129] The word seiðhjallr means "incantation scaffold", for performing magic.[103]

Hallucinogens

The notion of ecstatic experience induced or complemented by the use of intoxicants in the context of Nordic pagan religion is not new, and there have been several attempts to reconstruct such practices. Little evidence to confirm the Viking Age ingestion of hallucinogens such as psilocybin mushrooms or other entheogens has been found, with the exception of two archaeological finds:[130]

Several hundred seeds of henbane were found in grave 4 at Fyrkat. Their presence in the grave is likely significant, and the herb's deliriant properties suggest aspects of the rituals that might have been performed with it. There are many medieval accounts describing henbane's use as an ingredient in witches' ointments, used when a sorceress wished to change physical form. Henbane contains the psychoactive drug scopolamine, and when consumed as a tea, or when its juice is made into a topical salve and rubbed into the skin, especially around the armpits and chest, hallucinations can be experienced. A strong sensation of flight is often felt, which remains vivid for several hours.[130] Bilsenkraut, the German name of henbane, is derived from the Indo-European bhelena; according to some sources, it originally meant "plant of madness". The proto-Germanic bil seems to have meant "vision, hallucination" or "magical power."[131]

Four seeds of the mind-altering plant cannabis sativa were found in the Oseberg ship burial, among the piles of pillows thrown into the prow of the ship when the grave was robbed. A single seed of cannabis was also found embedded in a clump of decayed leather, bound by a thin woollen cord, apparently the remains of a small leather pouch with a draw-string; it is possible that all the seeds were originally contained in this bag. The pouch was too small to hold enough seeds for planting, suggesting that they might have had symbolic significance,[130] and could have been connected with the higher status woman's religious functions.[132]

Cats

All over the world cats are often linked to magical practices, and the goddess Freyja, who was the first divinity reported to have practiced magic, was associated with cats.[133] Cats and catskins appear to have been important symbols for the seeresses. In Eiríks saga rauða, the account of Þorbjörg lítilvölva tells that her ritual dress had a black lambskin hood that was lined with white catskin and on her hands she wore catskin gloves.[134][135][136] Ellis Davidson argues that the catskin represents the seeresses' helping animal spirits (see the section on magical projection, above),[137] and Price connects these cat spirits with the cats that pull Freyja's wagon.[138]

The most opulent female grave from the Viking Age is the extremely rich Oseberg ship burial from the first half of the 9th c. that contained two women. Although previously considered to be the grave of a queen, several scholars, such as Stine Ingstad, Neil Price and Leszek Gardeła note that the finds indicate that it was instead the grave of a seeress. In addition to a staff and cannabis it contained a chest with catskins,[139][98] and a wagon that had one end decorated with nine cats (a significant number), animals sacred to Freyja ,[140] which suggests that it was a reference to the goddess whose wagon is pulled by cats, according to Gylfaginning and Skáldskaparmál.[141] About 50 graves from Medelpad, the Mälaren Valley and Gotland, most of which are identified as the graves of wealthy women, contain lynx skins; it has been argued that these powerful women had a special connection with the goddess Freyja.[142]

Christianity

The seeresses rarely appear in the earliest Scandinavian written sources, such as runestones and skaldic poetry, and they do not appear in place names which suggests a marginal position in society; older research has cast them in a negative light.[143] Simek comments that all our sources on Germanic seeresses have passed through the filter of Roman and Christian interpretations. The Romans interpreted them as similar to their augurs, while the Christian writers considered them to be "more or less witches".[129] In sources from the Christian era, their rituals are described as suspicious and sometimes evil. This attitude can even be seen in some Eddic lays, and in the Ynglinga saga, Snorri Sturluson writes that their practice was so evil that "manly men considered it to shameful to practise it, and so it was taught to priestesses".[144] It is possible that the Christian scribes wanted to minimize and deprecate them and their rites and turn them into an oddity.[143] Price comments that the associations with Freyja and the Vanir gods lingered for a long time in Christian medieval Scandinavia, but the Viking Age views were replaced by negative views influenced by Christian attitudes towards female sexuality as something dangerous that had to be contained. This was related to the same fears that later led to witchcraft hysteria, manifested as what Ellis Davidson referred to as “the sinister light which played round [Freyja’s] cult for the story-tellers of a Christian age”.[145][138]

Modern archaeological finds, however, do not confirm that the North Germanic seeresses had a marginal position at the bottom of society as depicted by older scholarship and Christian sources, but instead they suggest the contrary.[143] The seeresses have been cast in a new light by a recent detailed analysis of Landnámabók, the Íslendingasögur and the Íslendingaþættir, which point out that the practitioners of magic were respected and well integrated in society. They were often connected to the highest echelons of society, they were free and they owned land. In a Norwegian setting they usually belong to Norwegian families, and in Iceland they do not live in caves or on islands, but in settlements with other people. Nor are they described as perverted or as sexual deviants.[143] Moreover, archaeological studies from Norway and Sweden, such as that of the Oseberg burial, show that they belonged to the highest elite and were part of aristocratic society.[146]

Late Middle Ages

The seeresss tradition did not disappear, at least not during the Middle Ages. Mitchell writes in his book Witchcraft and Magic in the Nordic Middle Ages (2011) that not even the most triumphalist Christian, nor even the most sceptic scholar, can deny the continued survival of the practices of these women. However, it is also clear that during centuries of transmission, their practices changed through external influences, and evolved.[147] Attitudes also changed and sorcery was increasingly considered to be witchcraft during the Middle Ages, and by the 15th century society appears no longer to have distinguished between sorcesses and healers such as midwives and wise women. The witch was inherently evil, she could fly to the sabbath and have intercourse with the devil, and she ate infants.[148]

Witch-hunts

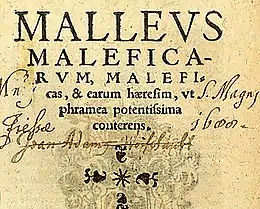

The Malleus Maleficarum extended the concept of "witch" to more women, and concepts that used to be separate – folklore and witchcraft - merged with the concept of heresy. Morris argues that without this book there would probably never have been witch-hunts, and that the printing press helped spread the notion of diabolical witchcraft from the ecclesiastical elite to a larger part of the population. This was also the time of the revival of "high magic" during the renaissance, but the Church did not separate the two and persecuted both the "low magic" and "high magic" as heresy. About eighty per cent of those accused of witchcraft were women, and the accusations included Devil worship, having sex with the Devil, sex both oral and anal, incest and cannibalism of infants. Morris comments that the accusations reveal more about the inquisitors than about the women who were accused. The accusations were characterized by ecclesiastical attitudes towards female sexuality, and it is notable that the practices they were accused of were preventive to procreation. Morris argues that the evolution from Germanic pagan seeresses to witches during the witch-hunts is a case study in how attitudes towards magic were affected by the change of religion.[148]

Modern influence

The concept of the Germanic seeress has had influence in a variety of areas of popular culture. For example, in 1965, the Icelandic scholar Sigurður Nordal coined the Icelandic language term for computer—tölva— by blending the words tala (number) and völva.[149]

The seeress Veleda has inspired a number of artworks, including German writer Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's 1818 novel Welleda und Ganna, an 1844 marble statue by French sculptor Hippolyte Maindron, an illustration, Veleda, die Prophetin der Brukterer, by K. Sigrist, and Polish-American composer Eduard Sobolewski's 1836 opera Velleda.[150]

Practitioners of Germanic Heathenry, the modern revival of Germanic paganism, seek to revive the concept of the Germanic seeress.[151]

See also

- Göndul, a name meaning 'wand-wielder' applied to a valkyrie in the Old Norse corpus and later appearing in a 14th-century charm used as evidence in a Norwegian witchcraft trial

- Norse cosmology, the cosmology of the North Germanic peoples

- Vitki, a term for a sorcerer among the North Germanic peoples

Notes

- MacLeod & Mees 2006, p. 5.

- de Vries 1970, p. 322f.

- Dowden 2000, p. 253.

- Orel 2003, p. 155.

- Orel 2003, p. 155f.

- Orel 2003, pp. 155, 310.

- Koch 2020, p. 137.

- Damico 1984, p. 212.

- Orel 2003, p. 149f.

- Mitchell 2011, p. 250.

- Kluge 2011, p. 414f.

- Strömbäck 2000, p. 234.

- Orel 2003, p. 150.

- Strömbäck 2000, p. 234f.

- Price 2019, pp. 72ff.

- Price 2019, p. 75f.

- Price 2019, p. 76.

- Price 2019, p. 76f.

- Cleasby & Vigfússon 1874, p. 539f.

- Cleasby & Vigfússon 1874, p. 159.

- Cleasby & Vigfússon 1874, p. 222.

- Cleasby & Vigfússon 1874, p. 146.

- Cleasby & Vigfússon 1874, p. 164.

- Price 2019, p. 260.

- Tolley 2009, p. 588.

- Price 2019.

- Morris 1991, p. 30.

- Simek 2020, p. 280.

- Simek 2020, p. 279.

- Simek 1996, p. 99.

- Lincoln 1986, p. 45―50.

- Enright 1996, p. 210.

- Sundqvist 2002, p. 82.

- Näsström 2002, p. 106.

- Morris 1991, p. 173.

- Price 2019, p. 72.

- Orchard (1997: 174).

- Simek 2007 [1993]: 326).

- Birley (1999: 41).

- Jones (1924: 169-172).

- Cary (1917: 378-381).

- Wellesley (1964 [1972]: 247).

- de Vries 2000, p. 678.

- Lincoln 1986, p. 45–50.

- Simek 1996, p. 280.

- Enright 1996, p. 186f.

- Sundqvist 2020, p. 747.

- de Vries 1970, p. 321.

- Simek 1996, p. 370f.

- Reinach & Jullian 1920, p. 105f.

- Enright 1996, p. 187.

- Morris 1991, p. 31f.

- Morris 1991, p. 32.

- Orel 2003, p. 445.

- Schubart 1917, p. 9f.

- Simek 2020, p. 279f.

- Janson 2018, p. 16.

- Samplonius 2013, p. 87.

- Samplonius 2013, p. 87f.

- Samplonius 2013, p. 88.

- Pohl 2006, p. 149.

- Jarnut 1998.

- Hauck 1955, p. 186–223.

- Hauck 1955, p. 187.

- McKinnell 2005, p. 13.

- Hermann 2020, p. 61.

- Grundy 1996, p. 65.

- Mazo 2016, p. 243.

- Lindow 2001, p. 129, 176.

- Lindow 2001, p. 129.

- Grundy 1996, p. 65f.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 506.

- Foulke 1974, p. 16.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 59.

- Pohl 2006, p. 142.

- Hultgård 2005.

- Enright 1996, p. 65f.

- Wolfram 2006, p. 60.

- Wagner 1999, p. 138.

- Morris 1991, p. 148f.

- "Þórdís spákona (Þjóðsagnasafn Jóns Árnasonar)". Háskóli Íslands (in Icelandic). July 1998. Retrieved 2021-05-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Samplonius 2001, p. 185.

- Kunz 2000, pp. 653–674.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 503f.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 504f.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 508f.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 510f.

- Harrison & Svensson (2007: 69).

- Kovalev 2012, p. 510f, 513.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 461f.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 478ff.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 483.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 489–491ff.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 467.

- Kovalev 2012, p. 469.

- Price 2019, p. 280.

- Näsström 2009, p. 181.

- Price 2019, pp. 115ff.

- National Museum of Denmark website. Undated. "A seeress from Fyrkat?". Online. Last accessed August 21, 2019.

- National Museum of Denmark website. Undated. "The magic wands of Viking seeresses?". Online. Last accessed August 21, 2019.

- Sundqvist 2020, p. 774.

- Orel 2003, p. 124.

- Mitchell 2020, p. 655.

- Orel 2003, p. 123f.

- Mitchell 2020, p. 655f.

- Mitchell 2020, p. 657.

- Strömbäck 2000, p. 124f.

- Cleasby & Vigfússon 1874, p. 679f.

- Tolley 1995, p. 61.

- Price 2019, p. 170.

- Strömbäck 2000, p. 125.

- Morris 1991, p. 43.

- Tolley 1995, p. 61, note 10.

- Tolley 1995, p. 72.

- McKinnell 2005, p. 97.

- Price 2019, p. 133.

- Strömbäck 2000, p. 221.

- Tolley 1995, p. 67.

- Lindow 2001, p. 141.

- Jansson 1987, p. 24.

- Cleasby & Vigfússon 1874, p. 200.

- Tolley 1995, p. 67f.

- Mitchell 2011, p. 132.

- Price 2019, p. 136.

- Price 2019, p. 293f.

- McKinnell 2005, p. 97f.

- Tolley 1995, p. 58.

- Price 2019, p. 172.

- Simek 1996, p. 279.

- Price 2019, pp. 168–169.

- Metzner, Ralph (2001). The Well of Remembrance: Rediscovering the Earth Wisdom Myths of Northern Europe. Shambhala Publications. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-8348-2931-2.

- Clarke & Merlin 2016, pp. 259–260.

- Schjødt 2020, p. 790, note 8.

- Schjødt 2020, p. 788.

- Sundqvist 2020, pp. 774f, 778f.

- Price 2019, pp. 41, 127.

- Ellis Davidson 1964, p. 120.

- Price 2019, p. 69.

- Sundqvist 2020, p. 778.

- Price 2019, p. 115.

- Ásdísardóttir 2020, pp. 1278f, 1283, 1287, 1294.

- Ásdísardóttir 2020, p. 1294f.

- Sundqvist 2020, p. 777.

- Sundqvist 2020, p. 775f.

- Ellis Davidson 1964, p. 123.

- Sundqvist 2020, p. 778f.

- Mitchell 2011, p. 10f.

- Morris 1991, p. 174ff.

- Zhang (2015).

- Simek (2007 [1993]: 357).

- For discussion regarding examples of modern-day seeresses in Germanic Heathenry, see for example discussion throughout Blain 2002.

Sources

- Ásdísardóttir, Ingunn (2020). "Freyja". In Schjødt, J.P.; Lindow, J.; Andrén, A. (eds.). The Pre-Christian Religions of the North, History and Structures. Vol. III. Brepols. pp. 1273–1302. ISBN 978-2-503-57491-2.

- Birley, A. R. 1999. Trans. Tacitus, Agricola Germany. Oxford World's Classics.

- Cary, Earnest. 1917. Trans. Dio's Roman History, vol. 6. Harvard University Press. Available at Archive.org.

- Cary, Earnest. 1927. Trans. Dio's Roman History, vol. 8. Harvard University Press.

- Clarke, Robert; Merlin, Mark (2016). Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. Univ of California Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 978-0-520-29248-2.

- Cleasby, R.; Vigfússon, G. (1874). An Icelandic-English dictionary. Oxford Clarendon Press.

- Damico, Helen (1984). Beowulf's Wealhtheow and the Valkyrie Tradition. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-09500-2.

- Dowden, Ken (2000). European Paganism. The realities of cult from antiquity to the Middle Ages. Routledge, London and New York. ISBN 0-415-12034-9.

- Ellis Davidson, H.R. (1964). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Penguin Books.

- Enright, M.J. (1996). Lady with a Mead Cup. Four Courts Press. ISBN 1-85182-188-0.

- Grundy, Stephan (1996). "Freyja and Frigg". In Billington, Sandra; Green, Miranda (eds.). The Concept of the Goddess. Routledge, London and New York. pp. 56–67. ISBN 0-203-76462-5.

- Harrison, Dick & Svensson Kristina. (2007). Vikingaliv. Natur och Kultur.

- Hauck, K. (1955). "Lebensnormen und Kultmythen in germ. Stammes-und Herrschergenealogien". Saeculum. 6 (JG): 186–223. doi:10.7788/saeculum.1955.6.jg.186. S2CID 170200000.

- Hermann, Pernille (2020). "Memory, Oral Tradition, and Sources". In Schjødt, J.P; Lindow, J.; Andrén, A. (eds.). The Pre-Christian Religions of the North, History and Structures. Vol. I. Brepols. pp. 41–62. ISBN 978-2-503-57491-2.

- Hultgård, Anders (2005). "Seherinnen". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 28 (2010 ed.). De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/gao. ISBN 978-3-11-045562-5.

- Janson, Henrik (2018). "Pictured by the Other: Classical and Early Medieval Perspectives on Religions in the North". In Clunies Ross, Margaret (ed.). The Pre-Christian Religions of the North, Research and Reception, From the Middle Ages to c. 1830. Vol. I. Brepols. pp. 7–40. ISBN 978-2-503-56881-2.

- Jansson, Sven B.F. (1987). Runes in Sweden. Translated by Foote, Peter. Förlag Kungliga Vitterhetsakademien. ISBN 9789178440672.

- Jarnut, Jörg (1998). "Gambara". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 10 (2010 ed.). De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/gao. ISBN 978-3-11-045562-5.

- Jones, Horace Leonard. 1924. Trans. The Geography of Strabo, vol. 3. Harvard University Press. Available at Archive.org.

- Kluge, Friedrich (2011). Seebold, Elmar (ed.). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (25 ed.). De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022364-4.

- Koch, John T. (2020). Celto-Germanic, Later Prehistory and Post-Proto-Indo-European vocabulary in the North and West (PDF). Aberystwyth Canolfan Uwchefrydiau Cymreig a Cheltaidd Prifysgol Cymru, University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. ISBN 9781907029325.

- Kovalev, Roman K. (2012). "Grand Princess Olga of Rus' Shows the Bird: Her 'Christian Falcon' Emblem". Russian History. 39 (4): 460–517. doi:10.1163/48763316-03904002.

- Kunz, Keneva (2000). "Eirik the Red's Saga". In Thorsson, Orndélfur; Scudder, Bernard (eds.). The Sagas of Icelanders. Viking. pp. 653–674. ISBN 978-0-14-100003-9.

- Lindow, John (2001). Handbook of Norse Mythology. Handbooks of World Mythology. ABC-CLIO, Inc., Santa Barbara, California; Denver, Colorado; Oxford, England. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Lincoln, Bruce (1986). Myth, Cosmos, and Society; Indo-European Themes of Creation and Destruction. Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London. ISBN 0-674-59775-3.

- MacLeod, Mindy; Mees, Bernard (2006). Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. The Boydell Press, Woodbridge. ISBN 1-84383-205-4.

- Mazo, Jeffrey A. (2016). "Grímnismál". In Pulsiano, Philip; Wolf, Kirsten (eds.). Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-315-16132-7.

- McKinnell, John (2005). Meeting the Other in Norse Myth and Legend. D.S. Brewer, Cambridge. ISBN 1843840421.

- Mitchell, Stephen A. (2011). Witchcraft and Magic in the Nordic Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia & Oxford. ISBN 978-0-8122-4290-4.

- Mitchell, Stephen A. (2020). "Magic and Religion". In Schjødt, J.P; Lindow, J.; Andrén, A. (eds.). The Pre-Christian Religions of the North, History and Structures. Vol. II. Brepols. pp. 643–670. ISBN 978-2-503-57491-2.

- Morris, Katherine (1991). Sorceress Or Witch?: The Image of Gender in Medieval Iceland and Northern Europe. University Press of America. ISBN 9780819182579.

- Näsström, B.M. (1994). Freyja ― the Great Goddess of the North. Lund Studies in History of Religion. Vol. 5. Department of History of Religions, Lund.

- Näsström, B.M. (2002). Blot, tro och offer i det förkristna Norden. Norstedts. ISBN 91-7297-033-2.

- Näsström, B.M. (2009). Nordiska gudinnor : nytolkningar av den förkristna mytologin. Albert Bonniers Förlag. ISBN 9789100122379.

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassel, London. ISBN 0-304-34520-2.

- Orel, Vladimir E. (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12875-0.

- Peters, Edward, ed. (1974). Paul the Deacon, History of the Lombards. Translated by Foulke, William Dudley. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. ISBN 0-8122-1079-4.

- Pohl, Walter (2006). "Gender and ethnicity in the early middle ages". In Noble, Thomas F. X. (ed.). From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms. Psychology Press. pp. 139―156. ISBN 978-0-415-32742-8.

- Pohl, Walter (2018). "Narratives of Origin and Migration in Early Medieval Europe: Problems of Interpretation". The Medieval History Journal. 21 (2): 192–221. doi:10.1177/0971945818775460. S2CID 158374863.

- Price, Neil (2019). The Viking Way, Magic and Mind in Late Iron Age Scandinavia (2 ed.). Oxbow Books, Oxford and Philadelphia. ISBN 9781842172605.

- Reinach, Théodore; Jullian, C. (1920). "Une sorcière germaine aux bords du Nil". Revue des Études Anciennes. 22 (2): 104–106.

- Samplonius, Kees (2001). "Sibylla borealis: Notes on the Structure of Vǫluspá". In Olsen, Karin E.; Harbus, Antonina; Hofstra, Tette (eds.). Germanic Texts and Latin Models: Medieval Reconstructions. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-0985-4.

- Samplonius, Kees (2013) [1995]. "From Veleda to the Völva". In Mulder-Bakker, Anneke (ed.). Sanctity and Motherhood: Essays on Holy Mothers in the Middle Ages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-81949-2.

- Schjødt, Jens Peter (2020). "Crisis Rituals". In Schjødt, J.P; Lindow, J.; Andrén, A. (eds.). The Pre-Christian Religions of the North, History and Structures. Vol. II. Brepols. pp. 781–796. ISBN 978-2-503-57491-2.

- Schubart, W. (1917). "Ägyptische Abteilung (Papyrussammlung)". Amtliche Berichte aus den Königlichen Kunstsammlungen. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin -- Preußischer Kulturbesitz. 38 (12): 7–12. JSTOR 4235200.

- Simek, Rudolf (1996). Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 9780859915137.

- Simek, Rudolf (2020). "Encounters: Roman". In Schjødt, J.P; Lindow, J.; Andrén, A. (eds.). The Pre-Christian Religions of the North, History and Structures. Vol. I. Brepols. pp. 269–288. ISBN 978-2-503-57491-2.

- Strömbäck, Dag (2000). Gidlund, G. (ed.). Sejd och andra studier i nordisk själsuppfattning. Gidlunds förlag. ISBN 9178443180.

- Sundqvist, Olof (2002). Freyr's offspring, Rulers and religion in ancient Svea society. Uppsala universitet. ISBN 91-554-5263-9.

- Sundqvist, Olof (2020). "Cultic Leaders and Religious Specialists". In Schjødt, J.P.; Lindow, J.; Andrén, A. (eds.). The Pre-Christian Religions of the North, History and Structures. Vol. II. Brepols. pp. 739–780. ISBN 978-2-503-57491-2.

- Tolley, Clive (1995). "Vǫrðr and Gandr: Helping Spirits in Norse Magic". Arkiv för nordisk filologi. 110: 57–75.

- Tolley, Clive (2009). Shamanism in Norse myth and magic. FF communications, no. 296; 297. Vol. 1. Academia Scientiarum Fennica, Helsinki. ISBN 978-9514110283.

- de Vries, Jan (1970). Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte. Vol. I. Berlin: de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110865486. ISBN 978-3-11-002678-8.

- de Vries, Jan (1962). Altnordisches Etymologisches Worterbuch (2000 ed.). Brill. ISBN 90 04 05436 7.

- Wagner, Norbert (1999). Beck, Heinrich (ed.). Germanenprobleme in heutiger Sicht. Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde - Ergänzungsbände. Vol. 1. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110108064.

- Wellesley, Kenneth. 1972 [1964]. Trans. Tacitus, the Histories. Penguin Classics.

- Wolfram, Herwig (2006). "Gothic history as historical ethnography". In Noble, Thomas F. X. (ed.). From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms. Psychology Press. p. 57―74. ISBN 978-0-415-32742-8.

- Zhang, Sarah. 2019. "Icelandic Has the Best Words for Technology". Gizmodo, 5 July 2015. Online. Last accessed August 21, 2019.