Vietnamese language

Vietnamese (Vietnamese: tiếng Việt) is an Austroasiatic language originating from Vietnam where it is the national and official language. Vietnamese is spoken natively by over 70 million people, several times as many as the rest of the Austroasiatic family combined.[4] It is the native language of the Vietnamese (Kinh) people, as well as a second language or first language for other ethnic groups in Vietnam. As a result of emigration, Vietnamese speakers are also found in other parts of Southeast Asia, East Asia, North America, Europe, and Australia. Vietnamese has also been officially recognized as a minority language in the Czech Republic.[lower-alpha 1]

| Vietnamese | |

|---|---|

| Tiếng Việt | |

| Pronunciation | [tiəŋ˧˦ viə˨ʔ] (Northern) [tiəŋ˦˥ jḭiək̚˨˩˨] (Southern) |

| Native to | Vietnam China (Dongxing, Guangxi) |

| Ethnicity | Vietnamese (Kinh) |

Native speakers | 76 million (2009)[1] |

Austroasiatic

| |

Early forms | Viet–Muong

|

| Latin (Vietnamese alphabet) Vietnamese Braille Chữ Nôm (historical) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | vi |

| ISO 639-2 | vie |

| ISO 639-3 | vie |

| Glottolog | viet1252 |

| Linguasphere | 46-EBA |

Natively Vietnamese-speaking (non-minority) areas of Vietnam[3] | |

Like many other languages in Southeast Asia and East Asia, Vietnamese is an analytic language with phonemic tone. It has head-initial directionality, with subject–verb–object order and modifiers following the words they modify. It also uses noun classifiers. Its vocabulary has had significant influence from Chinese and French.

Vietnamese was historically written using Chữ Nôm, a logographic script using Chinese characters (Chữ Hán) to represent Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and some native Vietnamese words, together with many locally-invented characters to represent other words.[5][6] French colonial rule of Vietnam led to the official adoption of the Vietnamese alphabet (Chữ Quốc ngữ) which is based on Latin script. It uses digraphs and diacritics to mark tones and some phonemes.

Classification

Early linguistic work some 150 years ago[7] classified Vietnamese as belonging to the Mon–Khmer branch of the Austroasiatic language family (which also includes the Khmer language spoken in Cambodia, as well as various smaller and/or regional languages, such as the Munda and Khasi languages spoken in eastern India, and others in Laos, southern China and parts of Thailand). Later, Muong was found to be more closely related to Vietnamese than other Mon–Khmer languages, and a Viet–Muong subgrouping was established, also including Thavung, Chut, Cuoi, etc.[8] The term "Vietic" was proposed by Hayes (1992),[9] who proposed to redefine Viet–Muong as referring to a subbranch of Vietic containing only Vietnamese and Muong. The term "Vietic" is used, among others, by Gérard Diffloth, with a slightly different proposal on subclassification, within which the term "Viet–Muong" refers to a lower subgrouping (within an eastern Vietic branch) consisting of Vietnamese dialects, Muong dialects, and Nguồn (of Quảng Bình Province).[10]

History

Vietnamese belongs to the Northern (Viet–Muong) clusters of the Vietic branch, spoken by the Vietic peoples. The language was first recorded in the Tháp Miếu Temple Inscription, dating from early 13th century AD.[11] The inscription was carved on a stone stele, in combined Chữ Hán and archaic form of the Chữ Nôm.[12]

In the distant past, Vietnamese shared more characteristics common to other languages in South East Asia and with the Austroasiatic family, such as an inflectional morphology and a richer set of consonant clusters, which have subsequently disappeared from the language under Chinese influence. Vietnamese is heavily influenced by its location in the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, with the result that it has acquired or converged toward characteristics such as isolating morphology and phonemically distinctive tones, through processes of tonogenesis. These characteristics have become part of many of the genetically unrelated languages of Southeast Asia; for example, Tsat (a member of the Malayo-Polynesian group within Austronesian), and Vietnamese each developed tones as a phonemic feature. The ancestor of the Vietnamese language is usually believed to have been originally based in the area of the Red River Delta in what is now northern Vietnam.[13][14][15]

Distinctive tonal variations emerged during the subsequent expansion of the Vietnamese language and people into what is now central and southern Vietnam through conquest of the ancient nation of Champa and the Khmer people of the Mekong Delta in the vicinity of present-day Ho Chi Minh City, also known as Saigon.

Northern Vietnam was primarily influenced by Chinese, which came to predominate politically in the 2nd century BC. After the emergence of the first kingdom of the Viet at the beginning of the 10th century, the ruling class adopted Classical Chinese as the formal medium of government, scholarship and literature. With the dominance of Chinese came radical importation of Chinese vocabulary and grammatical influence. The resulting Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary makes up about a third of the Vietnamese lexicon in all realms, and may account for as much as 60% of the vocabulary used in formal texts.[16]

After France invaded Vietnam in the late 19th century, French gradually replaced Chinese as the official language in education and government. Vietnamese adopted many French terms, such as đầm ('dame', from madame), ga ('train station', from gare), sơ mi ('shirt', from chemise), and búp bê ('doll', from poupée).

Henri Maspero described six periods of the Vietnamese language:[17][18]

- Proto-Viet–Muong, also known as Pre-Vietnamese or Proto-Vietnamuong, the ancestor of Vietnamese and the related Muong language (before 7th century AD).

- Proto-Vietnamese, the oldest reconstructable version of Vietnamese, dated to just before the entry of massive amounts of Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary into the language, c. 7th to 9th century AD. At this state, the language had three tones.

- Archaic Vietnamese, the state of the language upon adoption of the Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and the beginning of creation of the Vietnamese characters during the Ngô Dynasty, c. 10th century AD.

- Ancient Vietnamese, the language represented by Chữ Nôm (c. 15th century), widely used during the Lê and the Chinese–Vietnamese, and the Ming glossary "Annanguo Yiyu" 安南國譯語 (c. 15th century) by the Bureau of Interpreters 会同馆 (from the series Huáyí Yìyǔ (Chinese: 华夷译语). By this point, a tone split had happened in the language, leading to six tones but a loss of contrastive voicing among consonants.

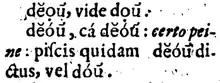

- Middle Vietnamese, the language of the Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum of the Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes (c. 17th century); the dictionary was published in Rome in 1651. Another famous dictionary of this period was written by P. J. Pigneau de Behaine in 1773 and published by Jean-Louis Taberd in 1838.

- Modern Vietnamese, from the 19th century.

Proto–Viet–Muong

The following diagram shows the phonology of Proto–Viet–Muong (the nearest ancestor of Vietnamese and the closely related Muong language), along with the outcomes in the modern language:[19][20][21][22]

Labial Dental/Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal Stop tenuis *p > b *t > đ *c > ch *k > k/c/q *ʔ > # voiced *b > b *d > đ *ɟ > ch *ɡ > k/c/q aspirated *pʰ > ph *tʰ > th *kʰ > kh implosive *ɓ > m *ɗ > n *ʄ > nh 1 Nasal *m > m *n > n *ɲ > nh *ŋ > ng/ngh Affricate *tʃ > x 1 Fricative voiceless *s > t *h > h voiced 2 *(β) > v 3 *(ð) > d *(r̝) > r 4 *(ʝ) > gi *(ɣ) > g/gh Approximant *w > v *l > l *r > r *j > d

^1 According to Ferlus, */tʃ/ and */ʄ/ are not accepted by all researchers. Ferlus 1992[19] also had additional phonemes */dʒ/ and */ɕ/.

^2 The fricatives indicated above in parentheses developed as allophones of stop consonants occurring between vowels (i.e. when a minor syllable occurred). These fricatives were not present in Proto-Viet–Muong, as indicated by their absence in Muong, but were evidently present in the later Proto-Vietnamese stage. Subsequent loss of the minor-syllable prefixes phonemicized the fricatives. Ferlus 1992[19] proposes that originally there were both voiced and voiceless fricatives, corresponding to original voiced or voiceless stops, but Ferlus 2009[20] appears to have abandoned that hypothesis, suggesting that stops were softened and voiced at approximately the same time, according to the following pattern:

- *p, *b > /β/

- *t, *d > /ð/

- *s > /r̝/

- *c, *ɟ, *tʃ > /ʝ/

- *k, *ɡ > /ɣ/

^3 In Middle Vietnamese, the outcome of these sounds was written with a hooked b (ꞗ), representing a /β/ that was still distinct from v (then pronounced /w/). See below.

^4 It is unclear what this sound was. According to Ferlus 1992,[19] in the Archaic Vietnamese period (c. 10th century AD, when Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary was borrowed) it was *r̝, distinct at that time from *r.

The following initial clusters occurred, with outcomes indicated:

- *pr, *br, *tr, *dr, *kr, *gr > /kʰr/ > /kʂ/ > s

- *pl, *bl > MV bl > Northern gi, Southern tr

- *kl, *gl > MV tl > tr

- *ml > MV ml > mnh > nh

- *kj > gi

A large number of words were borrowed from Middle Chinese, forming part of the Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary. These caused the original introduction of the retroflex sounds /ʂ/ and /ʈ/ (modern s, tr) into the language.

Origin of the tones

Proto-Viet–Muong had no tones to speak of. The tones later developed in some of the daughter languages from distinctions in the initial and final consonants. Vietnamese tones developed as follows:[23]

Register Initial consonant Smooth ending Glottal ending Fricative ending High (first) register Voiceless A1 ngang "level" B1 sắc "sharp" C1 hỏi "asking" Low (second) register Voiced A2 huyền "deep" B2 nặng "heavy" C2 ngã "tumbling"

Glottal-ending syllables ended with a glottal stop /ʔ/, while fricative-ending syllables ended with /s/ or /h/. Both types of syllables could co-occur with a resonant (e.g. /m/ or /n/).

At some point, a tone split occurred, as in many other mainland Southeast Asian languages. Essentially, an allophonic distinction developed in the tones, whereby the tones in syllables with voiced initials were pronounced differently from those with voiceless initials. (Approximately speaking, the voiced allotones were pronounced with additional breathy voice or creaky voice and with lowered pitch. The quality difference predominates in today's northern varieties, e.g. in Hanoi, while in the southern varieties the pitch difference predominates, as in Ho Chi Minh City.) Subsequent to this, the plain-voiced stops became voiceless and the allotones became new phonemic tones. Note that the implosive stops were unaffected, and in fact developed tonally as if they were unvoiced. (This behavior is common to all East Asian languages with implosive stops.)

As noted above, Proto-Viet–Muong had sesquisyllabic words with an initial minor syllable (in addition to, and independent of, initial clusters in the main syllable). When a minor syllable occurred, the main syllable's initial consonant was intervocalic and as a result suffered lenition, becoming a voiced fricative. The minor syllables were eventually lost, but not until the tone split had occurred. As a result, words in modern Vietnamese with voiced fricatives occur in all six tones, and the tonal register reflects the voicing of the minor-syllable prefix and not the voicing of the main-syllable stop in Proto-Viet–Muong that produced the fricative. For similar reasons, words beginning with /l/ and /ŋ/ occur in both registers. (Thompson 1976[22] reconstructed voiceless resonants to account for outcomes where resonants occur with a first-register tone, but this is no longer considered necessary, at least by Ferlus.)

Old Vietnamese

Old Vietnamese Phonology[24] Labial Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal Nasal m (m) n (n) nh (ɲ) ng/ngh (ŋ) Stop tenuis b/v ([p b]) d/đ ([t ɗ]) ch/gi (c) c/k/q ([k ɡ]) # (ʔ) aspirated ph (pʰ) th (tʰ) t/r (s) kh (kʰ) h (h) Implosive stop m (ɓ) n (ɗ) nh (ʄ) Fricative voiced v (v) d (j) Affricate x (tʃ) Liquid r [r] l [l]

Old Vietnamese/Ancient Vietnamese was a Vietic language which was separated from Viet–Muong around 9th century, and evolved to Middle Vietnamese by 16th century. The sources for the reconstruction of Old Vietnamese are Nom texts, such as the 12th-century/1486 Buddhist scripture Phật thuyết Đại báo phụ mẫu ân trọng kinh ("Sūtra explained by the Buddha on the Great Repayment of the Heavy Debt to Parents"),[25] old inscriptions, and late 13th-century (possibly 1293) Annan Jishi glossary by Chinese diplomat Chen Fu (c. 1259 – 1309).[26] Old Vietnamese used Chinese characters phonetically where each word, monosyllabic in Modern Vietnamese, is written with two Chinese characters or in a composite character made of two different characters.[27] It conveys the transformation of Vietnamese lexicons from sesquisyllabic to fully monosyllabic through monosyllabization process under pressures of Chinese linguistic influence, characterized by phenomena such as the reduction of minor syllables; loss of affixal morphology drifting towards analytical grammar; simplification of major syllable segments, and change of suprasegment instruments.[28]

For examples, the modern Vietnamese word "trời" (heaven) was read as *plời in Old/Ancient Vietnamese.

Middle Vietnamese

The writing system used for Vietnamese is based closely on the system developed by Alexandre de Rhodes for his 1651 Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum. It reflects the pronunciation of the Vietnamese of Hanoi at that time, a stage commonly termed Middle Vietnamese (tiếng Việt trung đại). The pronunciation of the "rime" of the syllable, i.e. all parts other than the initial consonant (optional /w/ glide, vowel nucleus, tone and final consonant), appears nearly identical between Middle Vietnamese and modern Hanoi pronunciation. On the other hand, the Middle Vietnamese pronunciation of the initial consonant differs greatly from all modern dialects, and in fact is significantly closer to the modern Saigon dialect than the modern Hanoi dialect.

The following diagram shows the orthography and pronunciation of Middle Vietnamese:

Labial Dental/

AlveolarRetroflex Palatal Velar Glottal Nasal m [m] n [n] nh [ɲ] ng/ngh [ŋ] Stop tenuis p [p]1 t [t] tr [ʈ] ch [c] c/k [k] aspirated ph [pʰ] th [tʰ] kh [kʰ] implosive b [ɓ] đ [ɗ] Fricative voiceless s/ſ [ʂ] x [ɕ] h [h] voiced ꞗ [β]2 d [ð] gi [ʝ] g/gh [ɣ] Approximant v/u/o [w] l [l] y/i/ĕ [j]3 Rhotic r [r]

.pdf.jpg.webp)

^1 [p] occurs only at the end of a syllable.

^2 This symbol, "Latin small letter B with flourish", looks like: ![]() . It has a rounded hook that starts halfway up the left side (where the top of the curved part of the b meets the vertical, straight part) and curves about 180 degrees counterclockwise, ending below the bottom-left corner.

. It has a rounded hook that starts halfway up the left side (where the top of the curved part of the b meets the vertical, straight part) and curves about 180 degrees counterclockwise, ending below the bottom-left corner.

^3 [j] does not occur at the beginning of a syllable, but can occur at the end of a syllable, where it is notated i or y (with the difference between the two often indicating differences in the quality or length of the preceding vowel), and after /ð/ and /β/, where it is notated ĕ. This ĕ, and the /j/ it notated, have disappeared from the modern language.

Note that b [ɓ] and p [p] never contrast in any position, suggesting that they are allophones.

The language also has three clusters at the beginning of syllables, which have since disappeared:

- tl /tl/ > modern tr

- bl /ɓl/ > modern gi (Northern), tr (Southern)

- ml /ml/ > mnh /mɲ/ > modern nh

Most of the unusual correspondences between spelling and modern pronunciation are explained by Middle Vietnamese. Note in particular:

- de Rhodes' system has two different b letters, a regular b and a "hooked" b in which the upper section of the curved part of the b extends leftward past the vertical bar and curls down again in a semicircle. This apparently represented a voiced bilabial fricative /β/. Within a century or so, both /β/ and /w/ had merged as /v/, spelled as v.

- de Rhodes' system has a second medial glide /j/ that is written ĕ and appears in some words with initial d and hooked b. These later disappear.

- đ /ɗ/ was (and still is) alveolar, whereas d /ð/ was dental. The choice of symbols was based on the dental rather than alveolar nature of /d/ and its allophone [ð] in Spanish and other Romance languages. The inconsistency with the symbols assigned to /ɓ/ vs. /β/ was based on the lack of any such place distinction between the two, with the result that the stop consonant /ɓ/ appeared more "normal" than the fricative /β/. In both cases, the implosive nature of the stops does not appear to have had any role in the choice of symbol.

- x was the alveolo-palatal fricative /ɕ/ rather than the dental /s/ of the modern language. In 17th-century Portuguese, the common language of the Jesuits, s was the apico-alveolar sibilant /s̺/ (as still in much of Spain and some parts of Portugal), while x was a palatoalveolar /ʃ/. The similarity of apicoalveolar /s̺/ to the Vietnamese retroflex /ʂ/ led to the assignment of s and x as above.

De Rhodes's orthography also made use of an apex diacritic, as in o᷄ and u᷄, to indicate a final labial-velar nasal /ŋ͡m/, an allophone of /ŋ/ that is peculiar to the Hanoi dialect to the present day. This diacritic is often mistaken for a tilde in modern reproductions of early Vietnamese writing.

Geographic distribution

As the national language, Vietnamese is the lingua franca in Vietnam. It is also spoken by the Gin traditionally residing on three islands (now joined to the mainland) off Dongxing in southern Guangxi Province, China.[29] A large number of Vietnamese speakers also reside in neighboring countries of Cambodia and Laos.

In the United States, Vietnamese is the fifth most spoken language, with over 1.5 million speakers, who are concentrated in a handful of states. It is the third most spoken language in Texas and Washington; fourth in Georgia, Louisiana, and Virginia; and fifth in Arkansas and California.[30] Vietnamese is the fourth most spoken language in Australia, after Arabic, Mandarin and English.[31] In France, it is the most spoken Asian language and the eighth most spoken immigrant language at home.[32]

Official status

Vietnamese is the sole official and national language of Vietnam. It is the first language of the majority of the Vietnamese population, as well as a first or second language for the country's ethnic minority groups.[33]

In the Czech Republic, Vietnamese has been recognized as one of 14 minority languages, on the basis of communities that have resided in the country either traditionally or on a long-term basis. This status grants the Vietnamese community in the country a representative on the Government Council for Nationalities, an advisory body of the Czech Government for matters of policy towards national minorities and their members. It also grants the community the right to use Vietnamese with public authorities and in courts anywhere in the country.[34][35]

As a foreign language

Vietnamese is increasingly being taught in schools and institutions outside of Vietnam, a large part which is contributed by its large diaspora. In countries with strongly established Vietnamese-speaking communities such as the United States, France, Australia, Canada, Germany, and the Czech Republic, Vietnamese language education largely serves as a cultural role to link descendants of Vietnamese immigrants to their ancestral culture. Meanwhile, in countries near Vietnam such as Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, the increased role of Vietnamese in foreign language education is largely due to the recent recovery of the Vietnamese economy.[36][37]

Since the 1980s, Vietnamese language schools (trường Việt ngữ/ trường ngôn ngữ Tiếng Việt) have been established for youth in many Vietnamese-speaking communities around the world, notably in the United States.[38][39]

Similarly, since the late 1980s, the Vietnamese-German community has enlisted the support of city governments to bring Vietnamese into high school curriculum for the purpose of teaching and reminding Vietnamese German students of their mother-tongue. Furthermore, there has also been a number of Germans studying Vietnamese due to increased economic investments and business.[40][41]

Historic and stronger trade and diplomatic relations with Vietnam and a growing interest among the French Vietnamese population (one of France's most established non-European ethnic groups) of their ancestral culture have also led to an increasing number of institutions in France, including universities, to offer formal courses in the language.[42]

Phonology

Vowels

Vietnamese has a large number of vowels. Below is a vowel diagram of Vietnamese from Hanoi (including centering diphthongs):

Front Central Back Centering ia/iê [iə̯] ưa/ươ [ɨə̯] ua/uô [uə̯] Close i/y [i] ư [ɨ] u [u] Close-mid/

Midê [e] ơ [əː]

â [ə]ô [o] Open-mid/

Opene [ɛ] a [aː]

ă [a]o [ɔ]

Front and central vowels (i, ê, e, ư, â, ơ, ă, a) are unrounded, whereas the back vowels (u, ô, o) are rounded. The vowels â [ə] and ă [a] are pronounced very short, much shorter than the other vowels. Thus, ơ and â are basically pronounced the same except that ơ [əː] is of normal length while â [ə] is short – the same applies to the vowels long a [aː] and short ă [a].[lower-alpha 2]

The centering diphthongs are formed with only the three high vowels (i, ư, u). They are generally spelled as ia, ưa, ua when they end a word and are spelled iê, ươ, uô, respectively, when they are followed by a consonant.

In addition to single vowels (or monophthongs) and centering diphthongs, Vietnamese has closing diphthongs[lower-alpha 3] and triphthongs. The closing diphthongs and triphthongs consist of a main vowel component followed by a shorter semivowel offglide /j/ or /w/.[lower-alpha 4] There are restrictions on the high offglides: /j/ cannot occur after a front vowel (i, ê, e) nucleus and /w/ cannot occur after a back vowel (u, ô, o) nucleus.[lower-alpha 5]

/w/ offglide /j/ offglide Front Central Back Centering iêu [iə̯w] ươu [ɨə̯w] ươi [ɨə̯j] uôi [uə̯j] Close iu [iw] ưu [ɨw] ưi [ɨj] ui [uj] Close-mid/

Midêu [ew] –

âu[əw]ơi [əːj]

ây [əj]ôi [oj] Open-mid/

Openeo [ɛw] ao [aːw]

au [aw]ai [aːj]

ay [aj]oi [ɔj]

The correspondence between the orthography and pronunciation is complicated. For example, the offglide /j/ is usually written as i; however, it may also be represented with y. In addition, in the diphthongs [āj] and [āːj] the letters y and i also indicate the pronunciation of the main vowel: ay = ă + /j/, ai = a + /j/. Thus, tay "hand" is [tāj] while tai "ear" is [tāːj]. Similarly, u and o indicate different pronunciations of the main vowel: au = ă + /w/, ao = a + /w/. Thus, thau "brass" is [tʰāw] while thao "raw silk" is [tʰāːw].

Consonants

The consonants that occur in Vietnamese are listed below in the Vietnamese orthography with the phonetic pronunciation to the right.

Labial Dental/

AlveolarRetroflex Palatal Velar Glottal Nasal m [m] n [n] nh [ɲ] ng/ngh [ŋ] Stop tenuis p [p] t [t] tr [ʈ] ch [c] c/k/q [k] aspirated th [tʰ] implosive b [ɓ] đ [ɗ] Fricative voiceless ph [f] x [s] s [ʂ~s] kh [x~kʰ] h [h] voiced v [v] d/gi [z~j] g/gh [ɣ] Approximant l [l] y/i [j] u/o [w] Rhotic r [r]

Some consonant sounds are written with only one letter (like "p"), other consonant sounds are written with a digraph (like "ph"), and others are written with more than one letter or digraph (the velar stop is written variously as "c", "k", or "q").

Not all dialects of Vietnamese have the same consonant in a given word (although all dialects use the same spelling in the written language). See the language variation section for further elaboration.

Syllable-final orthographic ch and nh in Vietnamese has had different analyses. One analysis has final ch, nh as being phonemes /c/, /ɲ/ contrasting with syllable-final t, c /t/, /k/ and n, ng /n/, /ŋ/ and identifies final ch with the syllable-initial ch /c/. The other analysis has final ch and nh as predictable allophonic variants of the velar phonemes /k/ and /ŋ/ that occur after the upper front vowels i /i/ and ê /e/; although they also occur after a, but in such cases are believed to have resulted from an earlier e /ɛ/ which diphthongized to ai (cf. ach from aic, anh from aing). (See Vietnamese phonology: Analysis of final ch, nh for further details.)

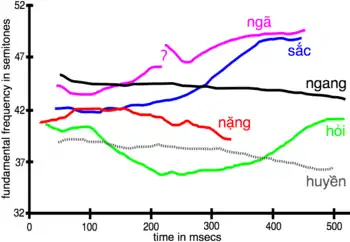

Tones

Each Vietnamese syllable is pronounced with one of six inherent tones,[lower-alpha 6] centered on the main vowel or group of vowels. Tones differ in:

- length (duration)

- pitch contour (i.e. pitch melody)

- pitch height

- phonation

Tone is indicated by diacritics written above or below the vowel (most of the tone diacritics appear above the vowel; however, the nặng tone dot diacritic goes below the vowel).[lower-alpha 7] The six tones in the northern varieties (including Hanoi), with their self-referential Vietnamese names, are:

| Name | Description | Contour | Diacritic | Example | Sample vowel | Unicode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ngang 'level' | mid level | ˧ | (no mark) | ma 'ghost' | ||

| huyền 'deep' | low falling (often breathy) | ˨˩ | ◌̀ (grave accent) | mà 'but' | U+0340 or U+0300 | |

| sắc 'sharp' | high rising | ˧˥ | ◌́ (acute accent) | má 'cheek, mother (southern)' | U+0341 or U+0301 | |

| hỏi 'questioning' | mid dipping-rising | ˧˩˧ | ◌̉ (hook above) | mả 'tomb, grave' | U+0309 | |

| ngã 'tumbling' | creaky high breaking-rising | ˧ˀ˦˥ | ◌̃ (tilde) | mã 'horse (Sino-Vietnamese), code' | U+0342 or U+0303 | |

| nặng 'heavy' | creaky low falling constricted (short length) | ˨˩ˀ | ◌̣ (dot below) | mạ 'rice seedling' | U+0323 |

Other dialects of Vietnamese may have fewer tones (typically only five).

| Tone | Northern dialect | Southern dialect | Central dialect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ngang (a) | |||

| Huyền (à) | |||

| Sắc (á) | |||

| Hỏi (ả) | |||

| Ngã (ã) | |||

| Nặng (ạ) |

In Vietnamese poetry, tones are classed into two groups: (tone pattern)

| Tone group | Tones within tone group |

|---|---|

| bằng "level, flat" | ngang and huyền |

| trắc "oblique, sharp" | sắc, hỏi, ngã, and nặng |

Words with tones belonging to a particular tone group must occur in certain positions within the poetic verse.

Vietnamese Catholics practice a distinctive style of prayer recitation called đọc kinh, in which each tone is assigned a specific note or sequence of notes.

Grammar

Vietnamese, like Chinese and many languages in Southeast Asia, is an analytic language. Vietnamese does not use morphological marking of case, gender, number or tense (and, as a result, has no finite/nonfinite distinction).[lower-alpha 8] Also like other languages in the region, Vietnamese syntax conforms to subject–verb–object word order, is head-initial (displaying modified-modifier ordering), and has a noun classifier system. Additionally, it is pro-drop, wh-in-situ, and allows verb serialization.

Some Vietnamese sentences with English word glosses and translations are provided below.

Minh

Minh

là

BE

giáo viên

teacher.

"Minh is a teacher."

Trí

Trí

13

13

tuổi

age

"Trí is 13 years old,"

Mai

Mai

có vẻ

seem

là

BE

sinh viên

student (college)

hoặc

or

học sinh.

student (under-college)

"Mai seems to be a college or high school student."

Tài

Tài

đang

PRES.CONT

nói.

talk

"Tài is talking."

Giáp

Giáp

rất

INT

cao.

tall

"Giáp is very tall."

Người

person

đó

that.DET

là

BE

anh

older brother

của

POSS

nó.

3.PRO

"That person is his/her brother."

Con

CL

chó

dog

này

DET

chẳng

NEG

bao giờ

ever

sủa

bark

cả.

all

"This dog never barks at all."

Nó

3.PRO

chỉ

just

ăn

eat

cơm

rice.FAM

Việt Nam

Vietnam

thôi.

only

"He/she/it only eats Vietnamese rice (or food, especially spoken by the elderly)."

Tôi

1.PRO

thích

like

con

CL

ngựa

horse

đen.

black

"I like the black horse."

Tôi

1.PRO

thích

like

cái

FOC

con

CL

ngựa

horse

đen

black

đó.

DET

"I like that black horse."

Hãy

HORT

ở lại

stay

đây

here

ít

few

phút

minute

cho tới

until

khi

when

tôi

1.PRO

quay

turn

lại.

come

"Please stay here for a few minutes until I come back."

Lexicon

Austroasiatic origins

Many early studies brainstormed Vietnamese language-origins to have been either Tai, Sino-Tibetan or Austroasiatic. Austroasiatic origins are so far the most tenable to date, with some of the oldest words in Vietnamese being Austroasiatic in origin.[44][45]

Ancient Chinese contact

Although Vietnamese roots are classified as Austroasiatic, Vietic and Viet-Muong, the result of language contact with Chinese heavily influenced the Vietnamese language, causing it to diverge from Viet-Muong into Vietnamese, which was seen to have split Vietnamese from Muong around the 10th to 11th century. For instance, the Vietnamese word quản lý, meaning management (noun) or manage (verb) is likely descended from the same word as guǎnlǐ (管理) in Chinese, kanri (管理, かんり) in Japanese, and gwanli (관리, 管理) in Korean. Instances of Chinese contact include the historical Nam Việt (aka Nanyue) as well as other periods of influences. Besides English and French which have made some contributions to Vietnamese language, Japanese loanwords into Vietnamese are also a more recently studied phenomenon.

Modern linguists describe modern Vietnamese having lost many Proto-Austroasiatic phonological and morphological features that original Vietnamese had.[46] The Chinese influence on Vietnamese corresponds to various periods when Vietnam was under Chinese rule, and subsequent influence after Vietnam became independent. Early linguists thought that this meant Vietnamese lexicon then received only two layers of Chinese words, one stemming from the period under actual Chinese rule and a second layer from afterwards. These words are grouped together as Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary.

However, according to linguist John Phan, “Annamese Middle Chinese” was already used and spoken in the Red River Valley by the 1st century CE, and its vocabulary significantly fused with the co-existing Proto-Viet-Muong language, the immediate ancestor of Vietnamese. He lists three major classes of Sino-Vietnamese borrowings:[47][48][49] Early Sino-Vietnamese (Han Dynasty (ca. 1st century CE) and Jin Dynasty (ca. 4th century CE), Late Sino-Vietnamese (Tang Dynasty), Recent Sino-Vietnamese (Ming Dynasty and afterwards)

French colonial era

Additionally, the French presence in Vietnam from 1777 to the Geneva Accords of 1954 resulted in significant influence from French into the Indochina region (Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam). "Cà phê" in Vietnamese was derived from the French café (coffee). Yogurt in Vietnamese is "sữa chua" (lit. "sour milk"), but also calqued from French (yaourt) into Vietnamese (da ua - /j/a ua). "Phô mai" (cheese) is also derived from the French fromage. Musical note was borrowed into Vietnamese as "nốt" or "nốt nhạc", from the French note de musique. The Vietnamese term for steering wheel is "vô lăng", a partial derivation from the French volant directionnel. The necktie (cravate in French) is rendered into Vietnamese as "cà vạt".

In addition, modern Vietnamese pronunciations of French names remain directly derived from the original French pronunciation ("Pa-ri" for Paris, "Mác-xây" for Marseille, "Boóc-đô" for Bordeaux, etc.), whereas pronunciations of other foreign names (Chinese excluded) are generally derived from English pronunciations.

English

Some English words were incorporated into Vietnamese as loan words, such as "TV" borrowed as "tivi", but still officially called truyền hình. Some other borrowings are calques, translated into Viet, for example, 'software' is translated into "phần mềm" (literally meaning "soft part"). Some scientific terms such as "biological cell" were derived from Chữ Hán, (細胞), whilst other scientific names such as "acetylcholine" are unaltered. Words like "peptide", may be seen as peptit.

Japanese

Japanese loanwords are a more recently studied phenomenon, with a paper by Nguyen & Le (2020) classifying three layers of Japanese loanwords, where the third layer was used by Vietnamese who studied Japanese and the first two layers being the main layers of borrowings that were derived from Japanese.[50] The first layer consisted of Kanji words created by Japanese to represent Western concepts that were not readily available in Chinese or Japanese, where by the end of the 19th century they were imported to other Asian languages.[51] This first layer was called Sino-Vietnamese words of Japanese-origins. For example, the Vietnamese term for "association club", câu lạc bộ, which was borrowed from Chinese (俱乐部; pinyin: jùlèbù; jyutping: keoi1 lok6 bou6), which was borrowed from Japanese (kanji: 倶楽部; katakana: クラブ; rōmaji: kurabu) which came from English ("club"), resulting in indirect borrowing from Japanese.

The second layer was from brief Japanese occupation of Vietnam from 1940 until 1945. However, Japanese cultural influence in Vietnam started significantly from the 1980s. This new, second layer of Japan-origin loanwords is distinctive from Sino-Vietnamese words of Japanese-origin in that they were borrowed directly from Japanese. This vocabulary included words representative of Japanese culture, such as kimono, sumo, samurai, and bonsai from modified Hepburn romanisation. These loanwords are coined as "new Japanese loanwords". A significant number of new Japanese loanwords were also of Chinese origin. Sometimes, the same concept can be described using both Sino-Vietnamese words of Japanese origin (first layer) and new Japanese loanwords (second layer). For example, judo can be referred to as both judo and nhu đạo, the Vietnamese reading of 柔道.[50]

Modern Chinese influence

Some words such as lạp xưởng from 臘腸 (Chinese sausage) primarily keeps to the Cantonese pronunciation, brought over from southern Chinese migrants, whereas in Hán-Việt, which has been described as being close to Middle Chinese pronunciation, is it actually pronounced lạp trường. However, the Cantonese term is the more well known name for Chinese sausage in Vietnam. Meanwhile, any new terms calqued from Chinese would be from Mandarin into Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation. Additionally, in southern provinces of Vietnam, the name xí ngầu can be used to refer to die, which may have derived from a Cantonese or Teochew idiom "xập xí, xập ngầu" (十四, 十五, Sino-Vietnamese: thập tứ, thập ngũ) meaning "fourteen, fifteen" meaning 'uncertain'.

Pure Vietnamese words

Other words, like muôn thuở meaning forever are seen to be purely Vietnamese invention, which used to be scribed Nôm characters, which were compounded Chinese characters, which are now written in romanized script.

Slang

Vietnamese slang (tiếng lóng) has changed over time. Vietnamese slang consists of pure Vietnamese words as well as words borrowed from other languages such as Mandarin or Indo-European languages.[52] It is estimated that Vietnamese slang that originated from Mandarin accounts for a tiny proportion of all Vietnamese slang (4.6% of surveyed data in newspapers).[52] On the other hand, slang that originated from Indo-European languages accounts for a more significant proportion (12%) and is much more common in today's uses.[52] Slang borrowed from these languages can be either transliteration or vernacular.[52] Some examples:

| Word | IPA | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Ex | /ɛk̚/, /ejk̚/ | a word borrowed from English used to describe ex-lover, usually pronounced similarly to ếch ("frog"). This is an example of vernacular slang.[52] |

| Sô | /ʂoː/ | a word derived from the English's word "show" which has the same meaning, usually pair with the word chạy ("to run") to make the phrase chạy sô, which translates in English to "running shows", but its everyday use has the same connotation as "having to do a lot of tasks within a short amount of time". This is an example of transliteration slang.[52] |

With the rise of the Internet, new slang is generated and popularized through social media. This more modern slang is commonly used among the younger generation in Vietnam. This more recent slang is mostly pure Vietnamese, and almost all the words are homonyms or some form of wordplay. Some examples:

| Word | IPA | Description |

|---|---|---|

| vãi | /vǎːj/ | One of the most popular slang in Vietnamese. Vãi can be a noun, or a verb depends on the context. It refers to a female pagoda-goer in its noun form and refers to spilling something over in its verb form. Nowadays, it's commonly used to emphasize an adjective or a verb. For example, ngon vãi ("so delicious"), sợ vãi ("so scary").[53] Similar uses to expletive, bloody. |

| trẻ trâu | /ʈɛ̌ːʈəw/ | A noun whose literal translation is "young buffalo". It is usually used to describe younger children or people who behave like a child, like putting on airs, and act foolishly to attract other people's attention (with negative actions, words, and thoughts).[54] |

| gấu | /ɣə̆́w/ | A noun meaning "bear". It is also commonly used to refer to someone's lover.[55] |

| gà | /ɣàː/ | A noun meaning "chicken". It is also commonly used to refer to someone's lack of ability to complete or compete in a task.[54] |

| cá sấu | /káːʂə́w/ | A noun meaning "crocodile". It is also commonly used to refer to someone's lack of beauty. The word sấu can be pronounced similar to xấu (ugly).[55] |

| thả thính | /tʰǎːtʰíŋ̟/ | A verb used to describe the action of dropping roasted bran as bait for fish. Nowadays, it is also used to describe the act of dropping hints to another person that one is attracted to.[55] |

| nha (and other variants) | /ɲaː/ | Similar to other particles: nhé, nghe, nhỉ, nhá. It can be used to end sentences. "Rửa chén, nhỉ" can mean "Wash the dishes... yeah?" [56] |

| dzô | /zoː/, /jow/ | Eye dialect of the word vô, meaning "in". The letter "z" which is not usually present in the Vietnamese alphabet, can be used for emphasis or for slang terms.[57] |

There are debates on the prevalence of uses of slang among young people in Vietnam, as certain teenspeak conversations become difficult to understand for older generations. Many critics believed that incorporating teenspeak or internet slang into daily conversation among teenagers would affect the formality and cadence of speech.[58] Others argue that it is not the slang that is the problem but rather the lack of communication techniques for the instant internet messaging era. They believe slang should not be dismissed, but instead, youth should be informed enough to know when to use them and when it is appropriate.[59]

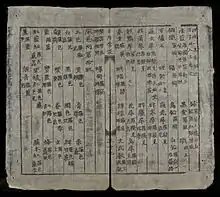

Writing systems

After ending a millennium of Chinese rule in 938, the Vietnamese state adopted Literary Chinese (called văn ngôn 文言 or Hán văn 漢文 in Vietnamese) for official purposes.[60] Up to the late 19th century (except for two brief interludes), all formal writing, including government business, scholarship and formal literature, was done in Literary Chinese, written with Chinese characters (chữ Hán).[61] Although the writing system is now mostly in chữ quốc ngữ (Latin script), Chinese script or Hán Tự as well as Chữ Nôm (together, Hán-Nôm) is still present in such activities such as Vietnamese calligraphy.

Chữ Nôm

From around the 13th century, Vietnamese scholars used their knowledge of the Chinese script to develop the chữ Nôm (lit. 'Southern characters') script to record folk literature in Vietnamese. The script used Chinese characters to represent both borrowed Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary and native words with similar pronunciation or meaning. In addition, thousands of new compound characters were created to write Vietnamese words using a variety of methods, including phono-semantic compounds.[62] For example, in the opening lines of the classic poem The Tale of Kieu,

- the Sino-Vietnamese word mệnh 'destiny' was written with its original character 命;

- the native Vietnamese word ta 'our' was written with the character 些 of the homophonous Sino-Vietnamese word ta 'little, few; rather, somewhat';

- the native Vietnamese word năm 'year' was written with a new character 𢆥 that is compounded from 南 nam and 年 'year'.

Nôm writing reached its zenith in the 18th century when many Vietnamese writers and poets composed their works in Nôm, most notably Nguyễn Du and Hồ Xuân Hương (dubbed "the Queen of Nôm poetry"). However, it was only used for official purposes during the brief Hồ and Tây Sơn dynasties (1400–1406 and 1778–1802 respectively).[63]

A Vietnamese Catholic, Nguyễn Trường Tộ, unsuccessfully petitioned the Court suggesting the adoption of a script for Vietnamese based on Chinese characters.[64][65]

Vietnamese alphabet

A romanization of Vietnamese was codified in the 17th century by the Avignonese Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes (1591–1660), based on works of earlier Portuguese missionaries, particularly Francisco de Pina, Gaspar do Amaral and Antonio Barbosa.[66][67] Still, chữ Nôm was the dominant script in Vietnamese Catholic literature for more than 200 years.[68] Starting from the late 19th century, the Vietnamese alphabet (chữ Quốc ngữ or "national language script") was gradually expanded from its initial usage in Christian writing to become more popular among the general public.

The Vietnamese alphabet contains 29 letters, including one digraph (đ) and nine with diacritics, five of which are used to designate tone (i.e. à, á, ả, ã, and ạ) and the other four used for separate letters of the Vietnamese alphabet (ă, â/ê/ô, ơ, ư).[69]

This romanized script became predominant over the course of the early 20th century, when education became widespread and a simpler writing system was found to be more expedient for teaching and communication with the general population. The French colonial administration sought to eliminate Chinese writing, Confucianism, and other Chinese influences from Vietnam.[65] French superseded Chinese in administration. Vietnamese written with the alphabet became required for all public documents in 1910 by issue of a decree by the French Résident Supérieur of the protectorate of Tonkin. In turn, Vietnamese reformists and nationalists themselves encouraged and popularized the use of chữ Quốc ngữ. By the middle of the 20th century, most writing was done in chữ Quốc ngữ, which became the official script on independence.

Nevertheless, chữ Hán was still in use during the French colonial period and as late as World War II was still featured on banknotes,[70][71] but fell out of official and mainstream use shortly thereafter. The education reform by North Vietnam in 1950 eliminated the use of 'chữ Hán and chữ Nôm.[72] Today, only a few scholars and some extremely elderly people are able to read chữ Nôm or use it in Vietnamese calligraphy. Priests of the Gin minority in China (descendants of 16th-century migrants from Vietnam) use songbooks and scriptures written in chữ Nôm in their ceremonies.[73]

Chữ Quốc ngữ reflects a "Middle Vietnamese" dialect that combines vowels and final consonants most similar to northern dialects with initial consonants most similar to southern dialects. This Middle Vietnamese is presumably close to the Hanoi variety as spoken sometime after 1600 but before the present. (This is not unlike how English orthography is based on the Chancery Standard of Late Middle English, with many spellings retained even after the Great Vowel Shift.)

Computer support

The Unicode character set contains all Vietnamese characters and the Vietnamese currency symbol. On systems that do not support Unicode, many 8-bit Vietnamese code pages are available such as Vietnamese Standard Code for Information Interchange (VSCII) or Windows-1258. Where ASCII must be used, Vietnamese letters are often typed using the VIQR convention, though this is largely unnecessary with the increasing ubiquity of Unicode. There are many software tools that help type Roman-script Vietnamese on English keyboards, such as WinVNKey and Unikey on Windows, or MacVNKey on Macintosh, with popular methods of encoding Vietnamese using Telex, VNI or VIQR input methods. Telex input method is often set as the default for many devices.

Dates and numbers writing formats

Vietnamese speak date in the format "day month year". Each month's name is just the ordinal of that month appended after the word tháng, which means "month". Traditional Vietnamese however assigns other names to some months; these names are mostly used in the lunar calendar and in poetry.

| English month name | Vietnamese month name | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Traditional | |

| January | Tháng Một | Tháng Giêng |

| February | Tháng Hai | |

| March | Tháng Ba | |

| April | Tháng Tư | |

| May | Tháng Năm | |

| June | Tháng Sáu | |

| July | Tháng Bảy | |

| August | Tháng Tám | |

| September | Tháng Chín | |

| October | Tháng Mười | |

| November | Tháng Mười Một | |

| December | Tháng Mười Hai | Tháng Chạp |

When written in the short form, "DD/MM/YYYY" is preferred.

Example:

- English: 28 March 2018

- Vietnamese long form: Ngày 28 tháng 3 năm 2018

- Vietnamese short form: 28/3/2018

The Vietnamese prefer writing numbers with a comma as the decimal separator in lieu of dots, and either spaces or dots to group the digits. An example is 1 629,15 (one thousand six hundred twenty-nine point fifteen). Because a comma is used as the decimal separator, a semicolon is used to separate two numbers instead.

Literature

The Tale of Kieu is an epic narrative poem by the celebrated poet Nguyễn Du, (阮攸), which is often considered the most significant work of Vietnamese literature. It was originally written in Chữ Nôm (titled Đoạn Trường Tân Thanh 斷腸新聲) and is widely taught in Vietnam (in chữ quốc ngữ transliteration).

Language variation

The Vietnamese language has several mutually intelligible regional varieties:[lower-alpha 9]

| Dialect region | Localities |

|---|---|

| Northern | Hà Nội, Hải Phòng, Red River Delta, Northwest and Northeast |

| North-Central (Area IV) | Thanh Hoá, Vinh, Hà Tĩnh |

| Mid-Central | Quảng Bình, Quảng Trị, Huế, Thừa Thiên |

| South-Central (Area V) | Đà Nẵng, Quảng Nam, Quảng Ngãi, Bình Định, Phú Yên, Nha Trang |

| Southern | Hồ Chí Minh, Lâm Đồng, Mê Kông, Southeast |

Vietnamese has traditionally been divided into three dialect regions: North, Central, and South. Michel Ferlus and Nguyễn Tài Cẩn also proved that there was a separate North-Central dialect for Vietnamese as well. The term Haut-Annam refers to dialects spoken from the northern Nghệ An Province to the southern (former) Thừa Thiên Province that preserve archaic features (like consonant clusters and undiphthongized vowels) that have been lost in other modern dialects.

These dialect regions differ mostly in their sound systems (see below), but also in vocabulary (including basic vocabulary, non-basic vocabulary, and grammatical words) and grammar.[lower-alpha 10] The North-central and Central regional varieties, which have a significant number of vocabulary differences, are generally less mutually intelligible to Northern and Southern speakers. There is less internal variation within the Southern region than the other regions due to its relatively late settlement by Vietnamese speakers (around the end of the 15th century). The North-central region is particularly conservative; its pronunciation has diverged less from Vietnamese orthography than the other varieties, which tend to merge certain sounds. Along the coastal areas, regional variation has been neutralized to a certain extent, while more mountainous regions preserve more variation. As for sociolinguistic attitudes, the North-central varieties are often felt to be "peculiar" or "difficult to understand" by speakers of other dialects, despite the fact that their pronunciation fits the written language the most closely; this is typically because of various words in their vocabulary which are unfamiliar to other speakers (see the example vocabulary table below).

The large movements of people between North and South beginning in the mid-20th century and continuing to this day have resulted in a sizable number of Southern residents speaking in the Northern accent/dialect and, to a greater extent, Northern residents speaking in the Southern accent/dialect. Following the Geneva Accords of 1954 that called for the temporary division of the country, about a million northerners (mainly from Hanoi, Haiphong and the surrounding Red River Delta areas) moved south (mainly to Saigon and heavily to Biên Hòa and Vũng Tàu, and the surrounding areas) as part of Operation Passage to Freedom. About 18% (~180,000) of that number of people made the move in the reverse direction (Tập kết ra Bắc, literally "go to the North".)

Following the reunification of Vietnam in 1975, Northern and North-Central speakers from the densely populated Red River Delta and the traditionally poorer provinces of Nghệ An, Hà Tĩnh, and Quảng Bình have continued to move South to look for better economic opportunities, beginning with the new government's "New Economic Zones program" which lasted from 1975 to 1985.[74] The first half of the program (1975–80), resulted in 1.3 million people sent to the New Economic Zones (NEZs), majority of which were relocated to the southern half of the country in previously uninhabited areas, of which 550,000 were Northerners.[74] The second half (1981–85) saw almost 1 million Northerners relocated to the NEZs.[74] Government and military personnel from Northern and North-central Vietnam are also posted to various locations throughout the country, often away from their home regions. More recently, the growth of the free market system has resulted in increased interregional movement and relations between distant parts of Vietnam through business and travel. These movements have also resulted in some blending of dialects, but more significantly, have made the Northern dialect more easily understood in the South and vice versa. Most Southerners, when singing modern/old popular Vietnamese songs or addressing the public, do so in the standardized accent if possible (which is Northern pronunciation). This is true in Vietnam as well as in overseas Vietnamese communities.

Modern Standard Vietnamese is based on the Hanoi dialect. Nevertheless, the major dialects are still predominant in their respective areas and have also evolved over time with influences from other areas. Historically, accents have been distinguished by how each region pronounces the letters d ([z] in the Northern dialect and [j] in the Central and Southern dialect) and r ([z] in the Northern dialect, [r] in the Central and Southern dialects). Thus, the Central and Southern dialects can be said to have retained a pronunciation closer to Vietnamese orthography and resemble how Middle Vietnamese sounded in contrast to the modern Northern (Hanoi) dialect which underwent shifts.

Vocabulary

| Northern | Central | Southern | English gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| vâng | dạ | dạ | "yes" |

| này | ni, nì | nè | "this" |

| thế này, như này | như ri | như vầy | "thus, this way" |

| đấy | nớ, tê | đó | "that" |

| thế, thế ấy, thế đấy | rứa, rứa tê | vậy, vậy đó | "thus, so, that way" |

| kia, kìa | tê, tề | đó | "that yonder" |

| đâu | mô | đâu | "where" |

| nào | mồ | nào | "which" |

| tại sao | răng | tại sao | "why" |

| thế nào, như nào | răng, làm răng | làm sao | "how" |

| tôi, tui | tui | tui | "I, me (polite)" |

| tao | tau | tao | "I, me (informal, familiar)" |

| chúng tao, bọn tao, chúng tôi, bọn tôi | choa, bọn choa | tụi tao, tụi tui, bọn tui | "we, us (but not you, colloquial, familiar)" |

| mày | mi | mày | "you (informal, familiar)" |

| chúng mày, bọn mày | bây, bọn bây | tụi mầy, tụi bây, bọn mày | "you guys (informal, familiar)" |

| nó | hắn | nó | "he/she/it (informal, familiar)" |

| chúng nó, bọn nó | bọn nớ | tụi nó | "they/them (informal, familiar)" |

| ông ấy | ông nớ | ông | "he/him, that gentleman, sir" |

| bà ấy | bà nớ | bà | "she/her, that lady, madam" |

| anh ấy | anh nớ | anh | "he/him, that young man (of equal status)" |

| ruộng | nương | ruộng,rẫy | "field" |

| bát | đọi | chén | "rice bowl" |

| muôi, môi | môi | vá | "ladle" |

| đầu | trốc | đầu | "head" |

| ô tô | ô tô | xe hơi (ô tô) | "car" |

| thìa | thìa | muỗng | "spoon" |

Although regional variations developed over time, most of these words can be used interchangeably and be understood well, albeit, with more or less frequency then others or with slightly different but often discernible word choices and pronunciations. Some accents may mix, with words such dạ vâng, combining dạ and vâng, being created.

Consonants

The syllable-initial ch and tr digraphs are pronounced distinctly in North-Central, Central, and Southern varieties, but are merged in Northern varieties (i.e. they are both pronounced the same way). Many North-Central varieties preserve three distinct pronunciations for d, gi, and r whereas the North has a three-way merger and the Central and South have a merger of d and gi while keeping r distinct. At the end of syllables, palatals ch and nh have merged with alveolars t and n, which, in turn, have also partially merged with velars c and ng in Central and Southern varieties.

| Syllable position | Orthography | Northern | North-central | Central | Southern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| syllable-initial | x | [s] | [s] | ||

| s | [ʂ] | [s, ʂ][lower-alpha 11] | |||

| ch | [t͡ɕ] | [c] | |||

| tr | [ʈ] | [c, ʈ][lower-alpha 11] | |||

| r | [z] | [r] | |||

| d | Varies | [j] | |||

| gi | Varies | ||||

| v | [v] | [v, j][lower-alpha 12] | |||

| syllable-final | t | [t] | [k] | ||

| c | [k] | ||||

| t after i, ê |

[t] | [t] | |||

| ch | [k̟] | ||||

| t after u, ô |

[t] | [kp] | |||

| c after u, ô, o |

[kp] | ||||

| n | [n] | [ŋ] | |||

| ng | [ŋ] | ||||

| n after i, ê |

[n] | [n] | |||

| nh | [ŋ̟] | ||||

| n after u, ô |

[n] | [ŋm] | |||

| ng after u, ô, o |

[ŋm] | ||||

In addition to the regional variation described above, there is a merger of l and n in certain rural varieties in the North:[76]

| Orthography | "Mainstream" varieties | Rural varieties |

|---|---|---|

| n | [n] | [l] |

| l | [l] |

Variation between l and n can be found even in mainstream Vietnamese in certain words. For example, the numeral "five" appears as năm by itself and in compound numerals like năm mươi "fifty" but appears as lăm in mười lăm "fifteen" (see Vietnamese grammar#Cardinal). In some northern varieties, this numeral appears with an initial nh instead of l: hai mươi nhăm "twenty-five", instead of mainstream hai mươi lăm.[lower-alpha 13]

There is also a merger of r and g in certain rural varieties in the South:

| Orthography | "Mainstream" varieties | Rural varieties |

|---|---|---|

| r | [r] | [ɣ] |

| g | [ɣ] |

The consonant clusters that were originally present in Middle Vietnamese (of the 17th century) have been lost in almost all modern Vietnamese varieties (but retained in other closely related Vietic languages). However, some speech communities have preserved some of these archaic clusters: "sky" is blời with a cluster in Hảo Nho (Yên Mô, Ninh Bình Province) but trời in Southern Vietnamese and giời in Hanoi Vietnamese (initial single consonants /ʈ/, /z/, respectively).

Tones

Although there are six tones in Vietnamese, some tones may slightly "merge", but are still highly distinguishable due to the context of the speech. The hỏi and ngã tones are distinct in North and some North-central varieties (although often with different pitch contours) but have somewhat merged in Central, Southern, and some North-Central varieties (also with different pitch contours). Some North-Central varieties (such as Hà Tĩnh Vietnamese) have a slight merger of the ngã and nặng tones while keeping the hỏi tone distinct. Still, other North-Central varieties have a three-way merger of hỏi, ngã, and nặng resulting in a four-tone system. In addition, there are several phonetic differences (mostly in pitch contour and phonation type) in the tones among dialects.

| Tone | Northern | North-central | Central | Southern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinh | Thanh Chương | Hà Tĩnh | ||||

| ngang | ˧ 33 | ˧˥ 35 | ˧˥ 35 | ˧˥ 35, ˧˥˧ 353 | ˧˥ 35 | ˧ 33 |

| huyền | ˨˩̤ 21̤ | ˧ 33 | ˧ 33 | ˧ 33 | ˧ 33 | ˨˩ 21 |

| sắc | ˧˥ 35 | ˩ 11 | ˩ 11, ˩˧̰ 13̰ | ˩˧̰ 13̰ | ˩˧̰ 13̰ | ˧˥ 35 |

| hỏi | ˧˩˧̰ 31̰3 | ˧˩ 31 | ˧˩ 31 | ˧˩̰ʔ 31̰ʔ | ˧˩˨ 312 | ˨˩˦ 214 |

| ngã | ˧ʔ˥ 3ʔ5 | ˩˧̰ 13̰ | ˨̰ 22̰ | |||

| nặng | ˨˩̰ʔ 21̰ʔ | ˨ 22 | ˨̰ 22̰ | ˨̰ 22̰ | ˨˩˨ 212 | |

The table above shows the pitch contour of each tone using Chao tone number notation (where 1 represents the lowest pitch, and 5 the highest); glottalization (creaky, stiff, harsh) is indicated with the ⟨◌̰⟩ symbol; murmured voice with ⟨◌̤⟩; glottal stop with ⟨ʔ⟩; sub-dialectal variants are separated with commas. (See also the tone section below.)

Word play

A basic form of word play in Vietnamese involves disyllabic words in which the last syllable forms the first syllable of the next word in the chain. This game involves two members versing each other until the opponent is unable to think of another word. For instance:

| Hậu Trường (backstage) | → | Trường Học (School) | → | Học Tập (Study) | → | Tập Trung (Concentrate) | → |

| Trung Tâm (Centre) | → | Tâm Lý (Mentality) | → | Lý Do (Reason) | → | Etc., until someone cannot form the next word or gives up. |

Another language game known as nói lái is used by Vietnamese speakers.[77] Nói lái involves switching, adding or removing the tones in a pair of words and may also involve switching the order of words or the first consonant and the rime of each word. Some examples:

Original phrase Phrase after nói lái transformation Structural change đái dầm "(child) pee" → dấm đài (literal translation "vinegar stage") word order and tone switch chửa hoang "pregnancy out of wedlock" → hoảng chưa "scared yet?" word order and tone switch bầy tôi "all the king's subjects" → bồi tây "west waiter" initial consonant, rime, and tone switch bí mật "secrets" → bật mí "reveal" initial consonant and rime switch Tây Ban Nha "Spain (España)" → Tây Bán Nhà (literal translation "Westerner selling home") initial consonant, rime, and tone switch

The resulting transformed phrase often has a different meaning but sometimes may just be a nonsensical word pair. Nói lái can be used to obscure the original meaning and thus soften the discussion of a socially sensitive issue, as with dấm đài and hoảng chưa (above), or when implied (and not overtly spoken), to deliver a hidden subtextual message, as with bồi tây.[lower-alpha 14] Naturally, nói lái can be used for a humorous effect.[78]

Another word game somewhat reminiscent of pig latin is played by children. Here a nonsense syllable (chosen by the child) is prefixed onto a target word's syllables, then their initial consonants and rimes are switched with the tone of the original word remaining on the new switched rime.

Nonsense syllable Target word Intermediate form with prefixed syllable Resulting "secret" word la phở "beef or chicken noodle soup" → la phở → lơ phả la ăn "to eat" → la ăn → lăn a la hoàn cảnh "situation" → la hoàn la cảnh → loan hà lanh cả chim hoàn cảnh "situation" → chim hoàn chim cảnh → choan hìm chanh kỉm

This language game is often used as a "secret" or "coded" language useful for obscuring messages from adult comprehension.

See also

- Vietnamese Wikipedia

- Vietnamese calligraphy

- Vietnamese pronouns

- Vietnamese studies

Notes

- Citizens belonging to minorities, which traditionally and on long-term basis live within the territory of the Czech Republic, enjoy the right to use their language in communication with authorities and in front of the courts of law (for the list of recognized minorities see National Minorities Policy of the Government of the Czech Republic, Belorussian and Vietnamese since 4 July 2013, see Česko má nové oficiální národnostní menšiny. Vietnamce a Bělorusy). The article 25 of the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms ensures right of the national and ethnic minorities for education and communication with authorities in their own language. Act No. 500/2004 Coll. (The Administrative Rule) in its paragraph 16 (4) (Procedural Language) ensures, that a citizen of the Czech Republic, who belongs to a national or an ethnic minority, which traditionally and on long-term basis lives within the territory of the Czech Republic, have right to address an administrative agency and proceed before it in the language of the minority. In the case that the administrative agency doesn't have an employee with knowledge of the language, the agency is bound to obtain a translator at the agency's own expense. According to Act No. 273/2001 (About The Rights of Members of Minorities) paragraph 9 (The right to use language of a national minority in dealing with authorities and in front of the courts of law) the same applies for the members of national minorities also in front of the courts of law.

- There are different descriptions of Hanoi vowels. Another common description is that of (Thompson 1991):

Front Central Back unrounded rounded Centering ia~iê [iə̯] ưa~ươ [ɯə̯] ua~uô [uə̯] Close i [i] ư [ɯ] u [u] Close-mid ê [e] ơ [ɤ] ô [o] Open-mid e [ɛ] ă [ɐ] â [ʌ] o [ɔ] Open a [a]

- In Vietnamese, diphthongs are âm đôi.

- The closing diphthongs and triphthongs as described by Thompson can be compared with the description above:

/w/ offglide /j/ offglide Centering iêu [iə̯w] ươu [ɯə̯w] ươi [ɯə̯j] uôi [uə̯j] Close iu [iw] ưu [ɯw] ưi [ɯj] ui [uj] Close-mid êu [ew] –

âu [ʌw]ơi [ɤj]

ây [ʌj]ôi [oj] Open-mid eo [ɛw] oi [ɔj] Open ao [aw]

au [ɐw]ai [aj]

ay [ɐj]

- The lack of diphthong consisting of a ơ + back offglide (i.e., [əːw]) is an apparent gap.

- Tone is called thanh điệu or thanh in Vietnamese. Tonal language in Vietnamese translates to ngôn ngữ âm sắc.

- Note that the name of each tone has the corresponding tonal diacritic on the vowel.

- Comparison note: As such its grammar relies on word order and sentence structure rather than morphology (in which word changes through inflection). Whereas European languages tend to use morphology to express tense, Vietnamese uses grammatical particles or syntactic constructions.

- Sources on Vietnamese variation include: Alves (forthcoming), Alves & Nguyễn (2007), Emeneau (1947), Hoàng (1989), Honda (2006), Nguyễn, Đ.-H. (1995), Pham (2005), Thompson (1991[1965]), Vũ (1982), Vương (1981).

- Some differences in grammatical words are noted in Vietnamese grammar: Demonstratives, Vietnamese grammar: Pronouns.

- In southern dialects, ch and tr are increasingly being merged as [c]. Similarly, x and s are increasingly being merged as [s].

- In southern dialects, v is increasingly being pronounced [v] among educated speakers. Less educated speakers have [j] more consistently throughout their speech.

- Gregerson (1981) notes that this variation was present in de Rhodes's time in some initial consonant clusters: mlẽ ~ mnhẽ "reason" (cf. modern Vietnamese lẽ "reason").

- Nguyễn 1997, p. 29 gives the following context: "... a collaborator under the French administration was presented with a congratulatory panel featuring the two Chinese characters quần thần. This Sino-Vietnamese expression could be defined as bầy tôi meaning 'all the king's subjects'. But those two syllables, when undergoing commutation of rhyme and tone, would generate bồi tây meaning 'servant in a French household'."

References

- Vietnamese at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)

- "Languages of ASEAN". Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- From Ethnologue (2009, 2013)

- Driem, George van (2001). Languages of the Himalayas, Volume One. BRILL. p. 264. ISBN 90-04-12062-9.

Of the approximately 90 millions speakers of Austroasiatic languages, over 70 million speak Vietnamese, nearly ten million speak Khmer and roughly five million speak Santali.

- "Vietnamese literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- Li, Yu (2020). The Chinese Writing System in Asia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Routledge. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-1-00-069906-7.

- "Mon–Khmer languages: The Vietic branch". SEAlang Projects. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- Ferlus, Michel. 1996. Langues et peuples viet-muong. Mon-Khmer Studies 26. 7–28.

- Hayes, La Vaughn H (1992). "Vietic and Việt-Mường: a new subgrouping in Mon-Khmer". Mon-Khmer Studies. 21: 211–228.

- Diffloth, Gérard. (1992). "Vietnamese as a Mon-Khmer language". Papers from the First Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, 125–128. Tempe, Arizona: Program for Southeast Asian Studies.

- Holcombe, Charles (2017). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-10810-777-8.

- Kornicki, Peter (2018). Languages, Scripts, and Chinese Texts in East Asia. Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-192-51869-9.

- Sagart, Laurent (2008), "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia", Past human migrations in East Asia: matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics, pp. 141–145

- Ferlus, Michael (2009). "A Layer of Dongsonian Vocabulary in Vietnamese". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 1: 105.

- Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - DeFrancis (1977), p. 8.

- Maspero, Henri (1912). "Études sur la phonétique historique de la langue annamite" [Studies on the phonetic history of the Annamite language]. Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in French). 12 (1): 10. doi:10.3406/befeo.1912.2713.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà (2009), "Vietnamese", in Comrie, Bernard (ed.), The World's Major Languages (2nd ed.), Routledge, pp. 677–692, ISBN 978-0-415-35339-7.

- Ferlus, Michel (1992), "Histoire abrégée de l'évolution des consonnes initiales du Vietnamien et du Sino-Vietnamien", Mon–Khmer Studies, 20: 111–125.

- Ferlus, Michel (2009), "A layer of Dongsonian vocabulary in Vietnamese", Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, 1: 95–109.

- Ferlus, Michel (1982), "Spirantisation des obstruantes médiales et formation du système consonantique du vietnamien", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 11 (1): 83–106, doi:10.3406/clao.1982.1105.

- Thompson, Laurence C. (1976), "Proto-Viet–Muong Phonology", Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications, Austroasiatic Studies Part II, University of Hawai'i Press, 13: 1113–1203, JSTOR 20019198.

- Haudricourt, André-Georges (2017). "La place du Vietnamien dans les langues Austroasiatiques" [The place of Vietnamese in Austroasiatic (1953)]. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris. 49 (1): 122–128.

- Maasaki 2015, pp. 143–155.

- Gong 2019, p. 60.

- Nguyen 2018, p. 162.

- Gong 2019, pp. 58–59.

- Gong 2019, p. 58.

- Tsung, Linda (2014). Language Power and Hierarchy: Multilingual Education in China. Bloomsbury. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4411-4235-1.

- MLA Language Map Data Center, Modern Language Association, retrieved 2018-01-20

- "2021 Australia, Census All persons QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics".

- La dynamique des langues en France au fil du XXe siècle Insee, enquête Famille 1999. (in French)

- "Vietnamese language". Britannica.

- "National Minorities | Government of the Czech Republic". www.vlada.cz.

- Česko má nové oficiální národnostní menšiny. Vietnamce a Bělorusy (in Czech)

- More Thai Students Interested in Learning ASEAN Languages Archived 2015-01-10 at the Wayback Machine. April 16, 2014. The Government Public Relations Department. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- Times, Vietnam (May 30, 2020). "More and more foreigners have need to learn Vietnamese". Vietnam Times.

- Nguyen, Angie; Dao, Lien, eds. (May 18, 2007). "Vietnamese in the United States" (PDF). California State Library. p. 82. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- Lam, Ha (2008). "Vietnamese Immigration". In González, Josué M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. pp. 884–887. ISBN 978-1-4129-3720-7.

- Vietnamese teaching and learning overwhelming Germany. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- School in Berlin maintains Vietnamese language. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- Blanc, Marie-Eve (2004), "Vietnamese in France", in Ember, Carol (ed.), Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World, Springer, p. 1162, ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9

- Deborah, H.-F., W., H. B., & T., E. H. (2002). Characteristics of Vietnamese Phonology. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(3), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2002/031)

- Haudricourt, André-Georges (2017). "La place du Vietnamien dans les langues Austroasiatiques" [The place of Vietnamese in Austroasiatic (1953)]. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris. 49 (1): 122–128.

- Alves, Mark (2006-02-01). "Linguistic Research on the Origins of the Vietnamese Language: An Overview". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 1 (1–2): 104–130. doi:10.1525/vs.2006.1.1-2.104.

- LaPolla, Randy J. (2010). ""Language Contact and Language Change in the History of the Sinitic Languages."". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2 (5): 6858–6868. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.05.036.

- Phan, John (2013-01-28). "Lacquered Words: The Evolution Of Vietnamese Under Sinitic Influences From The 1St Century Bce Through The 17Th Century Ce".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Phan, John D. & de Sousa, Hilário (2016). "(Paper presented at the International workshop on the history of Colloquial Chinese – written and spoken, Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ, 11–12 March 2016.)" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Phan, John (2010). ""Re-Imagining 'Annam': A New Analysis of Sino–Viet–Muong Linguistic Contact"". Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies. 4: 3–24.

- Nguyen & Le (2020). "Japanese Loanwords Adopted into the Vietnamese Language" (PDF). Asian and African Languages and Linguistics. 14: 21.

- Chung (2001). "Some returned loans, Japanese loanwords in Taiwan Mandarin". Language Change in East Asia: 161–179.

- "Tiếng lóng trên các phương tiện truyền thông hiện nay". khoavanhoc-ngonngu.edu.vn.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Vãi là gì? Tại sao các bạn trẻ lại hay sử dụng từ này?". tbtvn.org. 2020-07-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "10 từ lóng thường dùng của giới trẻ ngày nay". vnexpress.net. 2016-06-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "10 từ lóng thường dùng của giới trẻ ngày nay". vnexpress.net. 2016-06-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "What is the difference between "nhé" and "nha, nghe, nhà, nhỉ" ? "nhé" vs "nha, nghe, nhà, nhỉ" ?". hinative.com. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- "Vã mồ hôi "giải mã" tiếng lóng tuổi teen – Xã hội – VietNamNet". vietnamnet.vn. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- "Lo ngại thực trạng sử dụng ngôn ngữ mạng trong học sinh". baoninhbinh.org.vn. 2018-12-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Lạm dụng tiếng lóng trong giới trẻ – Thực trạng đáng báo động". hanoimoi.com.vn. 2013-10-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Hannas, Wm. C. (1997). Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 78–79, 82. ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

- Marr 1984, p. 141.

- DeFrancis 1977, p. 24–26.

- DeFrancis 1977, pp. 32, 38.

- DeFrancis 1977, pp. 101–105.

- Marr 1984, p. 145.

- Jacques, Roland (2002). Portuguese Pioneers of Vietnamese Linguistics Prior to 1650 – Pionniers Portugais de la Linguistique Vietnamienne Jusqu'en 1650 (in English and French). Bangkok, Thailand: Orchid Press. ISBN 974-8304-77-9.

- Trần, Quốc Anh; Phạm, Thị Kiều Ly (October 2019). Từ Nước Mặn đến Roma: Những đóng góp của các giáo sĩ Dòng Tên trong quá trình La tinh hoá tiếng Việt ở thế kỷ 17. Conference 400 năm hình thành và phát triển chữ Quốc ngữ trong lịch sử loan báo Tin Mừng tại Việt Nam. Hochiminh City: Committee on Culture, Catholic Bishops' Conference of Vietnam.

- Ostrowski, Brian Eugene (2010). "The Rise of Christian Nôm Literature in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam: Fusing European Content and Local Expression". In Wilcox, Wynn (ed.). Vietnam and the West: New Approaches. Ithaca, New York: SEAP Publications, Cornell University Press. pp. 23, 38. ISBN 9780877277828.

- admin (2014-02-05). "Vietnamese Language History". Vietnamese Culture and Tradition. Retrieved 2021-01-30.

- "French Indochina 500 Piastres 1951". art-hanoi.com.

- "North Vietnam 5 Dong 1946". art-hanoi.com.

- Vũ Thế Khôi (2009). "Ai “bức tử” chữ Hán-Nôm?".

- Friedrich, Paul; Diamond, Norma, eds. (1994). "Jing". Encyclopedia of World Cultures, volume 6: Russia and Eurasia / China. New York: G.K. Hall. p. 454. ISBN 0-8161-1810-8.

- Desbarats, Jacqueline. "Repression in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam: Executions and Population Relocation". Indochina report; no. 11. Executive Publications, Singapore 1987. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- Table data from Hoàng (1989).

- Kirby (2011), p. 382.

- Nguyễn 1997, pp. 28–29.

- www.users.bigpond.com/doanviettrung/noilai.html Archived 2008-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, Language Log's itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/001788.html, and tphcm.blogspot.com/2005/01/ni-li.html for more examples.

Bibliography

General

- Dương, Quảng-Hàm. (1941). Việt-nam văn-học sử-yếu [Outline history of Vietnamese literature]. Saigon: Bộ Quốc gia Giáo dục.

- Emeneau, M. B. (1947). "Homonyms and puns in Annamese". Language. 23 (3): 239–244. doi:10.2307/409878. JSTOR 409878.

- ——— (1951). Studies in Vietnamese (Annamese) grammar. University of California publications in linguistics. Vol. 8. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hashimoto, Mantaro (1978). "Current developments in Sino-Vietnamese studies". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 6 (1): 1–26. JSTOR 23752818.

- Marr, David G. (1984). Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920–1945. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-90744-7.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà (1995). NTC's Vietnamese–English dictionary (updated ed.). Lincolnwood, Illinois: NTC. ISBN 0-8442-8357-6.

- ——— (1997). Vietnamese: Tiếng Việt không son phấn. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 90-272-3809-X.

- Nguyen, Dinh Tham (2018). Studies on Vietnamese Language and Literature: A Preliminary Bibliography. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-501-71882-3.

- Rhodes, Alexandre de (1991). L. Thanh; X. V. Hoàng; Q. C. Đỗ (eds.). Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum. Hanoi: Khoa học Xã hội.

- Thompson, Laurence C. (1991) [1965]. A Vietnamese reference grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1117-8.

- Uỷ ban Khoa học Xã hội Việt Nam. (1983). Ngữ-pháp tiếng Việt [Vietnamese grammar]. Hanoi: Khoa học Xã hội.

Sound system

- Brunelle, Marc (2009). "Tone perception in Northern and Southern Vietnamese". Journal of Phonetics. 37 (1): 79–96. doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2008.09.003.

- Brunelle, Marc (2009). "Northern and Southern Vietnamese Tone Coarticulation: A Comparative Case Study" (PDF). Journal of Southeast Asian Linguistics. 1: 49–62. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-11-13.

- Kirby, James P. (2011). "Vietnamese (Hanoi Vietnamese)" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 41 (3): 381–392. doi:10.1017/S0025100311000181. S2CID 144227569.

- Michaud, Alexis (2004). "Final consonants and glottalization: New perspectives from Hanoi Vietnamese". Phonetica. 61 (2–3): 119–146. doi:10.1159/000082560. PMID 15662108. S2CID 462578.

- Nguyễn, Văn Lợi; Edmondson, Jerold A (1998). "Tones and voice quality in modern northern Vietnamese: Instrumental case studies". Mon–Khmer Studies. 28: 1–18.

- Thompson, Laurence E (1959). "Saigon phonemics". Language. 35 (3): 454–476. doi:10.2307/411232. JSTOR 411232.

Language variation

- Alves, Mark J. 2007. "A Look At North-Central Vietnamese" In SEALS XII Papers from the 12th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2002, edited by Ratree Wayland et al. Canberra, Australia, 1–7. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University