Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain is a term describing the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its satellite states from open contact with the West and its allied states. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were the countries that were connected to or influenced by the Soviet Union, while on the west side were the countries that were NATO members or nominally neutral. Separate international economic and military alliances were developed on each side of the Iron Curtain. It later became a term for the 7,000-kilometre-long (4,300 mi) physical barrier of fences, walls, minefields, and watchtowers that divided the "east" and "west". The Berlin Wall was also part of this physical barrier.

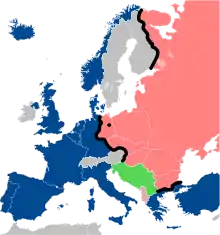

The black dot represents West Berlin. Albania withheld its support to the Warsaw Pact in 1961 due to the Soviet–Albanian split and formally withdrew in 1968.

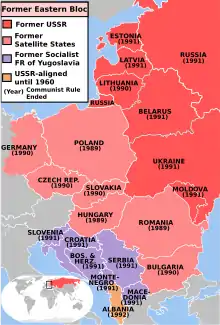

The nations to the east of the Iron Curtain were Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, and the USSR; however, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and the USSR have since ceased to exist. Countries that made up the USSR were Russia, Belarus, Latvia, Ukraine, Estonia, Moldova, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Lithuania, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan. The events that demolished the Iron Curtain started with peaceful opposition in Poland,[1][2] and continued into Hungary, East Germany, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia. Romania became the only socialist state in Europe to overthrow its government with violence.[3][4]

The use of the term "Iron Curtain" as a metaphor for strict separation goes back at least as far as the early 19th century. It originally referred to fireproof curtains in theaters.[5] Its popularity as a Cold War symbol is attributed to its use in a speech Winston Churchill gave on 5 March 1946, in Fulton, Missouri.[5]

On the one hand, the Iron Curtain was a separating barrier between the power blocs and, on the other hand, natural biotypes were formed here, as the European Green Belt shows today, or original cultural, ethnic or linguistic areas such as the area around Trieste were preserved.

Pre-Cold War usage

In the 19th century, iron safety curtains were installed on theater stages to slow the spread of fire.

Perhaps the first recorded application of the term "iron curtain" to Soviet Russia was in Vasily Rozanov's 1918 polemic The Apocalypse of Our Time. It is possible that Churchill read it there following the publication of the book's English translation in 1920. The passage runs:

With clanging, creaking, and squeaking, an iron curtain is lowering over Russian History. "The performance is over." The audience got up. "Time to put on your fur coats and go home." We looked around, but the fur coats and homes were missing.[6]

In 1920, Ethel Snowden, in her book Through Bolshevik Russia, used the term in reference to the Soviet border.[7][8]

A May 1943 article in Signal, a German propaganda periodical, discussed "the iron curtain that more than ever before separates the world from the Soviet Union".[9] Joseph Goebbels commented in Das Reich, on 25 February 1945, that if Germany should lose the war, "An iron curtain would fall over this enormous territory controlled by the Soviet Union, behind which nations would be slaughtered".[5][10] German foreign minister Lutz von Krosigk broadcast 2 May 1945: "In the East the iron curtain behind which, unseen by the eyes of the world, the work of destruction goes on, is moving steadily forward".[11]

Churchill's first recorded use of the term "iron curtain" came in a 12 May 1945 telegram he sent to U.S. President Harry S. Truman regarding his concern about Soviet actions, stating "[a]n iron curtain is drawn down upon their front. We do not know what is going on behind".[12][13]

He repeated it in another telegram to Truman on June 4, mentioning "...the descent of an iron curtain between us and everything to the eastward",[14] and in a House of Commons speech on 16 August 1945, stating "it is not impossible that tragedy on a prodigious scale is unfolding itself behind the iron curtain which at the moment divides Europe in twain".[15]

During the Cold War

Building antagonism

_-_preserved_part_of_Iron_curtain.JPG.webp)

The antagonism between the Soviet Union and the West that came to be described as the "iron curtain" had various origins.

During the summer of 1939, after conducting negotiations both with a British-French group and with Nazi Germany regarding potential military and political agreements,[16] the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the German–Soviet Commercial Agreement (which provided for the trade of certain German military and civilian equipment in exchange for Soviet raw materials)[17][18] and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact (signed in late August 1939), named after the foreign secretaries of the two countries (Vyacheslav Molotov and Joachim von Ribbentrop), which included a secret agreement to split Poland and Eastern Europe between the two states.[19][20]

The Soviets thereafter occupied Eastern Poland (September 1939), Latvia (June 1940), Lithuania (1940), northern Romania (Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, late June 1940), Estonia (1940) and eastern Finland (March 1940). From August 1939, relations between the West and the Soviets deteriorated further when the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany engaged in an extensive economic relationship by which the Soviet Union sent Germany vital oil, rubber, manganese and other materials in exchange for German weapons, manufacturing machinery and technology.[21][22] Nazi–Soviet trade ended in June 1941 when Germany broke the Pact and invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa.

In the course of World War II, Stalin determined to acquire a buffer area against Germany, with pro-Soviet states on its border in an Eastern bloc. Stalin's aims led to strained relations at the Yalta Conference (February 1945) and the subsequent Potsdam Conference (July–August 1945).[23] People in the West expressed opposition to Soviet domination over the buffer states, and the fear grew that the Soviets were building an empire that might be a threat to them and their interests.

Nonetheless, at the Potsdam Conference, the Allies assigned parts of Poland, Finland, Romania, Germany, and the Balkans to Soviet control or influence. In return, Stalin promised the Western Allies that he would allow those territories the right to national self-determination. Despite Soviet cooperation during the war, these concessions left many in the West uneasy. In particular, Churchill feared that the United States might return to its pre-war isolationism, leaving the exhausted European states unable to resist Soviet demands. (President Franklin D. Roosevelt had announced at Yalta that after the defeat of Germany, U.S. forces would withdraw from Europe within two years.)[24]

Churchill speech

Winston Churchill's "Sinews of Peace" address of 5 March 1946, at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, used the term "iron curtain" in the context of Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe:

From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia; all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject, in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and in some cases increasing measure of control from Moscow.[25]

Much of the Western public still regarded the Soviet Union as a close ally in the context of the recent defeat of Nazi Germany and of Imperial Japan. Although not well received at the time, the phrase iron curtain gained popularity as a shorthand reference to the division of Europe as the Cold War strengthened. The Iron Curtain served to keep people in, and information out. People throughout the West eventually came to accept and use the metaphor.

Churchill's "Sinews of Peace" address strongly criticised the Soviet Union's exclusive and secretive tension policies along with the Eastern Europe's state form, Police State (Polizeistaat). He expressed the Allied Nations' distrust of the Soviet Union after the World War II. In September 1946, US-Soviet cooperation collapsed due to the US disavowal of the Soviet Union's opinion on the German problem in the Stuttgart Council, and then followed the announcement by US President Harry S. Truman of a hard line anti-Soviet, anticommunist policy. After that the phrase became more widely used as an anti-Soviet term in the West.[26]

Additionally, Churchill mentioned in his speech that regions under the Soviet Union's control were expanding their leverage and power without any restriction. He asserted that in order to put a brake on this ongoing phenomenon, the commanding force and strong unity between the UK and the US was necessary.[27]

Stalin took note of Churchill's speech and responded in Pravda soon afterward. He accused Churchill of warmongering, and defended Soviet "friendship" with eastern European states as a necessary safeguard against another invasion. Stalin further accused Churchill of hoping to install right-wing governments in eastern Europe with the goal of agitating those states against the Soviet Union.[28] Andrei Zhdanov, Stalin's chief propagandist, used the term against the West in an August 1946 speech:[29]

Hard as bourgeois politicians and writers may strive to conceal the truth of the achievements of the Soviet order and Soviet culture, hard as they may strive to erect an iron curtain to keep the truth about the Soviet Union from penetrating abroad, hard as they may strive to belittle the genuine growth and scope of Soviet culture, all their efforts are foredoomed to failure.

Eastern Bloc

While the Iron Curtain remained in place, much of Eastern Europe and parts of Central Europe (except West Germany, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, and Austria) found themselves under the hegemony of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union annexed:

as Soviet Socialist Republics within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

Germany effectively gave Moscow a free hand in much of these territories in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, signed before Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.

Other Soviet-annexed territories included:

- Eastern Poland (incorporated into the Ukrainian and Byelorussian SSRs),[32]

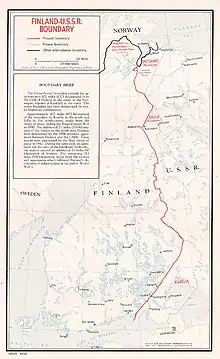

- Part of eastern Finland (became part of the Karelo-Finnish SSR)[33]

- Northern Romania (part of which became the Moldavian SSR).[34][35]

- Kaliningrad Oblast, the northern half of East Prussia, taken in 1945.

- Part of eastern Czechoslovakia (Carpathian Ruthenia, incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR).

Between 1945 and 1949 the Soviets converted the following areas into satellite states:

- The German Democratic Republic[36]

- The People's Republic of Bulgaria

- The People's Republic of Poland

- The Hungarian People's Republic[37]

- The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic[38]

- The People's Republic of Romania

- The People's Republic of Albania[39] (which re-aligned itself in the 1950s and early 1960s away from the Soviet Union towards the People's Republic of China (PRC) and split from the PRC towards a strongly isolationist worldview in the late 1970s)

Soviet-installed governments ruled the Eastern Bloc countries, with the exception of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which changed its orientation away from the Soviet Union in the late 1940s to a progressively independent worldview.

The majority of European states to the east of the Iron Curtain developed their own international economic and military alliances, such as Comecon and the Warsaw Pact.

West of the Iron Curtain

To the west of the Iron Curtain, the countries of Western Europe, Northern Europe, and Southern Europe – along with Austria, West Germany, Liechtenstein and Switzerland – operated market economies. With the exception of a period of fascism in Spain (until 1975) and Portugal (until 1974) and a military dictatorship in Greece (1967–1974), democratic governments ruled these countries.

Most of the states of Europe to the west of the Iron Curtain – with the exception of neutral Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Austria, Sweden, Finland, Malta and the Republic of Ireland – allied themselves with Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States within NATO. Spain was a unique anomaly in that it stayed neutral and non-aligned until 1982, when, following democracy's return, it joined NATO. Economically, the European Community (EC) and the European Free Trade Association represented Western counterparts to COMECON. Most of the nominally neutral states were economically closer to the United States than they were to the Warsaw Pact.

Further division in the late 1940s

In January 1947, Harry Truman appointed General George Marshall as Secretary of State, scrapped Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) directive 1067 (which embodied the Morgenthau Plan), and supplanted it with JCS 1779, which decreed that an orderly and prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany."[40] Officials met with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and others to press for an economically self-sufficient Germany, including a detailed accounting of the industrial plants, goods and infrastructure already removed by the Soviets.[41]

After five and a half weeks of negotiations, Molotov refused the demands and the talks were adjourned.[41] Marshall was particularly discouraged after personally meeting with Stalin, who expressed little interest in a solution to German economic problems.[41] The United States concluded that a solution could not wait any longer.[41] In a 5 June 1947 speech,[42] Marshall announced a comprehensive program of American assistance to all European countries wanting to participate, including the Soviet Union and those of Eastern Europe, called the Marshall Plan.[41]

Stalin opposed the Marshall Plan. He had built up the Eastern Bloc protective belt of Soviet-controlled nations on his Western border,[43] and wanted to maintain this buffer zone of states combined with a weakened Germany under Soviet control.[44] Fearing American political, cultural and economic penetration, Stalin eventually forbade Soviet Eastern bloc countries of the newly formed Cominform from accepting Marshall Plan aid.[41] In Czechoslovakia, that required a Soviet-backed Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948,[45] the brutality of which shocked Western powers more than any event so far and set in a motion a brief scare that war would occur and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to the Marshall Plan in the United States Congress.[46]

Relations further deteriorated when, in January 1948, the U.S. State Department also published a collection of documents titled Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939 – 1941: Documents from the Archives of The German Foreign Office, which contained documents recovered from the Foreign Office of Nazi Germany[47][48] revealing Soviet conversations with Germany regarding the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, including its secret protocol dividing eastern Europe,[49][50] the 1939 German-Soviet Commercial Agreement,[49][51] and discussions of the Soviet Union potentially becoming the fourth Axis Power.[52] In response, one month later, the Soviet Union published Falsifiers of History, a Stalin-edited and partially re-written book attacking the West.[47][53]

After the Marshall Plan, the introduction of a new currency to Western Germany to replace the debased Reichsmark and massive electoral losses for communist parties, in June 1948, the Soviet Union cut off surface road access to Berlin, initiating the Berlin Blockade, which cut off all non-Soviet food, water and other supplies for the citizens of the non-Soviet sectors of Berlin.[54] Because Berlin was located within the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, the only available methods of supplying the city were three limited air corridors.[55] A massive aerial supply campaign was initiated by the United States, Britain, France, and other countries, the success of which caused the Soviets to lift their blockade in May 1949.

Emigration restrictions

One of the conclusions of the Yalta Conference was that the western Allies would return all Soviet citizens who found themselves in their zones to the Soviet Union.[56] This affected the liberated Soviet prisoners of war (branded as traitors), forced laborers, anti-Soviet collaborators with the Germans, and anti-communist refugees.[57]

Migration from east to west of the Iron Curtain, except under limited circumstances, was effectively halted after 1950. Before 1950, over 15 million people (mainly ethnic Germans) emigrated from Soviet-occupied eastern European countries to the west in the five years immediately following World War II.[58] However, restrictions implemented during the Cold War stopped most east–west migration, with only 13.3 million migrations westward between 1950 and 1990.[59] More than 75% of those emigrating from Eastern Bloc countries between 1950 and 1990 did so under bilateral agreements for "ethnic migration."[59]

About 10% were refugees permitted to emigrate under the Geneva Convention of 1951.[59] Most Soviets allowed to leave during this time period were ethnic Jews permitted to emigrate to Israel after a series of embarrassing defections in 1970 caused the Soviets to open very limited ethnic emigrations.[60] The fall of the Iron Curtain was accompanied by a massive rise in European East-West migration.[59]

As a physical entity

The Iron Curtain took physical shape in the form of border defences between the countries of western and eastern Europe. There were some of the most heavily militarised areas in the world, particularly the so-called "inner German border" – commonly known as die Grenze in German – between East and West Germany. The inner German border was marked in rural areas by double fences made of steel mesh (expanded metal) with sharp edges, while near urban areas a high concrete barrier similar to the Berlin Wall was built. The installation of the Wall in 1961 brought an end to a decade during which the divided capital of divided Germany was one of the easiest places to move west across the Iron Curtain.[61]

The barrier was always a short distance inside East German territory to avoid any intrusion into Western territory. The actual borderline was marked by posts and signs and was overlooked by numerous watchtowers set behind the barrier. The strip of land on the West German side of the barrier – between the actual borderline and the barrier – was readily accessible but only at considerable personal risk, because it was patrolled by both East and West German border guards.

Several villages, many historic, were destroyed as they lay too close to the border, for example Erlebach. Shooting incidents were not uncommon, and several hundred civilians and 28 East German border guards were killed between 1948 and 1981 (some may have been victims of "friendly fire" by their own side).

Elsewhere along the border between West and East, the defence works resembled those on the intra-German border. During the Cold War, the border zone in Hungary started 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from the border. Citizens could only enter the area if they lived in the zone or had a passport valid for traveling out. Traffic control points and patrols enforced this regulation.

Those who lived within the 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) border-zone needed special permission to enter the area within 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) of the border. The area was very difficult to approach and heavily fortified. In the 1950s and 1960s, a double barbed-wire fence was installed 50 metres (160 ft) from the border. The space between the two fences was laden with land mines. The minefield was later replaced with an electric signal fence (about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from the border) and a barbed wire fence, along with guard towers and a sand strip to track border violations.

Regular patrols sought to prevent escape attempts. They included cars and mounted units. Guards and dog patrol units watched the border 24/7 and were authorised to use their weapons to stop escapees. The wire fence nearest the actual border was irregularly displaced from the actual border, which was marked only by stones. Anyone attempting to escape would have to cross up to 400 metres (1,300 ft) before they could cross the actual border. Several escape attempts failed when the escapees were stopped after crossing the outer fence.

In parts of Czechoslovakia, the border strip became hundreds of meters wide, and an area of increasing restrictions was defined as the border was approached. Only people with the appropriate government permissions were allowed to get close to the border.[62]

The Soviet Union built a fence along the entire border towards Norway and Finland. It is located one or a few kilometres from the border, and has automatic alarms detecting if someone climbs over it.

In Greece, a highly militarised area called the "Επιτηρούμενη Ζώνη" ("Surveillance Area") was created by the Greek Army along the Greek-Bulgarian border, subject to significant security-related regulations and restrictions. Inhabitants within this 25 kilometres (16 mi) wide strip of land were forbidden to drive cars, own land bigger than 60 square metres (650 sq ft), and had to travel within the area with a special passport issued by Greek military authorities. Additionally, the Greek state used this area to encapsulate and monitor a non-Greek ethnic minority, the Pomaks, a Muslim and Bulgarian-speaking minority which was regarded as hostile to the interests of the Greek state during the Cold War because of its familiarity with their fellow Pomaks living on the other side of the Iron Curtain.[63]

The Hungarian outer fence became the first part of the Iron Curtain to be dismantled. After the border fortifications were dismantled, a section was rebuilt for a formal ceremony. On 27 June 1989, the foreign ministers of Austria and Hungary, Alois Mock and Gyula Horn, ceremonially cut through the border defences separating their countries.

The creation of these highly militarised no-man's lands led to de facto nature reserves and created a wildlife corridor across Europe; this helped the spread of several species to new territories. Since the fall of the Iron Curtain, several initiatives are pursuing the creation of a European Green Belt nature preserve area along the Iron Curtain's former route. In fact, a long-distance cycling route along the length of the former border called the Iron Curtain Trail (ICT) exists as a project of the European Union and other associated nations. The trail is 6,800 km (4,200 mi) long and spans from Finland to Greece.[64]

The term "Iron Curtain" was only used for the fortified borders in Europe; it was not used for similar borders in Asia between socialist and capitalist states (these were, for a time, dubbed the Bamboo Curtain). The border between North Korea and South Korea is very comparable to the former inner German border, particularly in its degree of militarisation, but it has never conventionally been considered part of any Iron Curtain.

Helmstedt-Marienborn crossing

The Border checkpoint Helmstedt–Marienborn (German: Grenzübergang Helmstedt-Marienborn), named Grenzübergangsstelle Marienborn (GÜSt) (border crossing Marienborn) by the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was the largest and most important border crossing on the Inner German border during the division of Germany. Due to its geographical location, allowing for the shortest land route between West Germany and West Berlin, most transit traffic to and from West Berlin used the Helmstedt-Marienborn crossing. Most travel routes from West Germany to East Germany and Poland also used this crossing. The border crossing existed from 1945 to 1990 and was situated near the East German village of Marienborn at the edge of the Lappwald. The crossing interrupted the Bundesautobahn 2 (A 2) between the junctions Helmstedt-Ost and Ostingersleben.

Fall

Following a period of economic and political stagnation under Brezhnev and his immediate successors, the Soviet Union decreased its intervention in Eastern Bloc politics. Mikhail Gorbachev (General Secretary from 1985) decreased adherence to the Brezhnev Doctrine,[65] which held that if socialism were threatened in any state then other socialist governments had an obligation to intervene to preserve it, in favor of the "Sinatra Doctrine". He also initiated the policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (economic restructuring). A wave of revolutions occurred throughout the Eastern Bloc in 1989.[66]

Speaking at the Berlin Wall on 12 June 1987, Reagan challenged Gorbachev to go further, saying "General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!"

In February 1989, the Hungarian politburo recommended to the government led by Miklós Németh to dismantle the iron curtain. Nemeth first informed Austrian chancellor Franz Vranitzky. He then received an informal clearance from Gorbachev (who said "there will not be a new 1956") on 3 March 1989, on 2 May of the same year the Hungarian government announced and started in Rajka (in the locality known as the "city of three borders", on the border with Austria and Czechoslovakia) the destruction of the Iron Curtain. For public relation Hungary reconstructed 200m of the iron curtain so it could be cut during an official ceremony by Hungarian foreign minister Gyula Horn, and Austrian foreign minister Alois Mock, on 27 June 1989, which had the function of calling all European peoples still under the yoke of the national-communist regimes to freedom.[67] However, the dismantling of the old Hungarian border facilities did not open the borders, nor did the previous strict controls be removed, and the isolation by the Iron Curtain was still intact over its entire length. Despite dismantling the already technically obsolete fence, the Hungarians wanted to prevent the formation of a green border by increasing the security of the border or to technically solve the security of their western border in a different way. After the demolition of the border facilities, the stripes of the heavily armed Hungarian border guards were tightened and there was still a firing order.[68][69]

In April 1989, the People's Republic of Poland legalised the Solidarity organisation, which captured 99% of available parliamentary seats in June.[70] These elections, in which anti-communist candidates won a striking victory, inaugurated a series of peaceful anti-communist revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe[71][72][73] that eventually culminated in the fall of communism.[74][75]

The opening of a border gate between Austria and Hungary at the Pan-European Picnic on 19 August 1989 then set in motion a chain reaction, at the end of which there was no longer a GDR and the Eastern Bloc had disintegrated. The idea of opening the border at a ceremony came from Otto von Habsburg and was brought up by him to Miklós Németh, the then Hungarian Prime Minister, who promoted the idea.[76] The Paneuropa Picnic itself developed from a meeting between Ferenc Mészáros of the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF) and the President of the Paneuropean Union Otto von Habsburg in June 1989. The local organization in Sopron took over the Hungarian Democratic Forum, the other contacts were made via Habsburg and the Hungarian Minister of State Imre Pozsgay. Extensive advertising for the planned picnic was made by posters and flyers among the GDR holidaymakers in Hungary. The Austrian branch of the Paneuropean Union, which was then headed by Karl von Habsburg, distributed thousands of brochures inviting them to a picnic near the border at Sopron.[77][78] The local Sopron organizers knew nothing of possible GDR refugees, but thought of a local party with Austrian and Hungarian participation.[79] More than 600 East Germans attending the "Pan-European Picnic" on the Hungarian border broke through the Iron Curtain and fled into Austria. The refugees went through the iron curtain in three big waves during the picnic under the direction of Walburga Habsburg. Hungarian border guards had threatened to shoot anyone crossing the border, but when the time came, they did not intervene and allowed the people to cross.

It was the largest escape movement from East Germany since the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. The patrons of the picnic, Otto Habsburg and the Hungarian Minister of State Imre Pozsgay, who were not present at the event, saw the planned event as an opportunity to test Mikhail Gorbachev's reaction to an opening of the border on the Iron Curtain.[80] In particular, it was examined whether Moscow would give the Soviet troops stationed in Hungary the command to intervene.[81] After the pan-European picnic, Erich Honecker dictated the Daily Mirror of 19 August 1989: "Habsburg distributed leaflets far into Poland, on which the East German holidaymakers were invited to a picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given gifts, food and Deutsche Mark, and then they were persuaded to come to the West". But with the mass exodus at the Pan-European Picnic, the subsequent hesitant behavior of the Socialist Unity Party of East Germany and the non-intervention of the Soviet Union broke the dams. Thus the bracket of the Eastern Bloc was broken. Now tens of thousands of the media-informed East Germans made their way to Hungary, which was no longer ready to keep its borders completely closed or to oblige its border troops to use force of arms. The leadership of the GDR in East Berlin did not dare to completely lock the borders of their own country.[82][83]

In a historic session from 16 to 20 October, the Hungarian parliament adopted legislation providing for multi-party parliamentary elections and a direct presidential election.[84]

The legislation transformed Hungary from a People's Republic into the Republic, guaranteed human and civil rights, and created an institutional structure that ensured separation of powers among the judicial, legislative, and executive branches of government. In November 1989, following mass protests in East Germany and the relaxing of border restrictions in Czechoslovakia, tens of thousands of East Berliners flooded checkpoints along the Berlin Wall, crossing into West Berlin.[84]

In the People's Republic of Bulgaria, the day after the mass crossings across the Berlin Wall, leader Todor Zhivkov was ousted.[85] In the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, following protests of an estimated half-million Czechoslovaks, the government permitted travel to the west and abolished provisions guaranteeing the ruling Communist party its leading role, preceding the Velvet Revolution.[86]

In the Socialist Republic of Romania, on 22 December 1989, the Romanian military sided with protesters and turned on Communist ruler Nicolae Ceauşescu, who was executed after a brief trial three days later.[87] In the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, a new package of regulations went into effect on 3 July 1990 entitling all Albanians over the age of 16 to own a passport for foreign travel. Meanwhile, hundreds of Albanian citizens gathered around foreign embassies to seek political asylum and flee the country.

The Berlin Wall officially remained guarded after 9 November 1989, although the inter-German border had become effectively meaningless. The official dismantling of the Wall by the East German military did not begin until June 1990. On 1 July 1990, the day East Germany adopted the West German currency, all border-controls ceased and West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl convinced Gorbachev to drop Soviet objections to a reunited Germany within NATO in return for substantial German economic aid to the Soviet Union.

Otto von Habsburg, who played a leading role in opening the Iron Curtain

Otto von Habsburg, who played a leading role in opening the Iron Curtain Erich Honecker

Erich Honecker East German border guards look through a hole in the Berlin Wall in 1990

East German border guards look through a hole in the Berlin Wall in 1990

Monuments

There is an Iron Curtain monument in the southern part of the Czech Republic at approximately 48.8755°N 15.87477°E. A few hundred meters of the original fence, and one of the guard towers, has remained installed. There are interpretive signs in Czech and English that explain the history and significance of the Iron Curtain. This is the only surviving part of the fence in the Czech Republic, though several guard towers and bunkers can still be seen. Some of these are part of the Communist Era defences, some are from the never-used Czechoslovak border fortifications in defence against Adolf Hitler, and some towers were, or have become, hunting platforms.

Another monument is located in Fertőrákos, Hungary, at the site of the Pan-European Picnic. On the eastern hill of the stone quarry stands a metal sculpture by Gabriela von Habsburg. It is a column made of metal and barbed wire with the date of the Pan-European Picnic and the names of participants. On the ribbon under the board is the Latin text: In necessariis unitas – in dubiis libertas – in omnibus caritas ("Unity in unavoidable matters – freedom in doubtful matters – love in all things"). The memorial symbolises the Iron Curtain and recalls forever the memories of the border breakthrough in 1989.

Another monument is located in the village of Devín, now part of Bratislava, Slovakia, at the confluence of the Danube and Morava rivers.

There are several open-air museums in parts of the former inner German border, as for example in Berlin and in Mödlareuth, a village that has been divided for several hundred years. The memory of the division is being kept alive in many places along the Grenze.

Analogous terms

Throughout the Cold War the term "curtain" would become a common euphemism for boundaries – physical or ideological – between socialist and capitalist states.

- An analogue of the Iron Curtain, the Bamboo Curtain, surrounded the People's Republic of China. As the standoff between the West and the countries of the Iron and Bamboo curtains eased with the end of the Cold War, the term fell out of any but historical usage.

- The short distance, 3.8 km (2.4 mi), between the Soviet Union (Big Diomede) and the U.S. (Little Diomede Island, state of Alaska) in the Bering Sea became known as the "Ice Curtain" during the Cold War.

- A field of cacti surrounding the U.S. Naval station at Guantanamo Bay planted by Cuba was occasionally termed the "Cactus Curtain".[88][89]

- The phrase "Grass Curtain" was used by South Sudanese during the First Sudanese Civil War to describe the oppression that hid political violence in Southern Sudan from wider attention.[90]

See also

- Bamboo Curtain

- Danube River Conference of 1948

- EV13 The Iron Curtain Trail, a long-distance cycling route within the European Green Belt

- Removal of Hungary's border fence

- Telephone tapping in the Eastern Bloc

- Western betrayal

References

Notes

- Spain joined NATO in 1982.

Citations

- Sorin Antohi and Vladimir Tismăneanu, "Independence Reborn and the Demons of the Velvet Revolution" in Between Past and Future: The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Aftermath, Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9116-71-8. p.85.

- Boyes, Roger (4 June 2009). "World Agenda: 20 years later, Poland can lead eastern Europe once again". The Times. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Lucian-Dumitru Dîrdală, The End of the Ceauşescu Regime – A Theoretical Convergence (PDF)

- Piotr Sztompka, preface to Society in Action: the Theory of Social Becoming, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-78815-6. p. x.

- Feuerlicht, Ignace (October 1955), "A New Look at the Iron Curtain", American Speech, 30 (3): 186–189, doi:10.2307/453937, JSTOR 453937

- Rozanov, Vasily (1918), Апокалипсис нашего времени [The Apocalypse of our Time], p. 212

- Cohen, J. M.; Cohen, M. J. (1996), New Penguin Dictionary of Quotations, Penguin Books, p. 726, ISBN 0-14-051244-6

- Snowden, Philip (Ethel) (1920), Through Bolshevik Russia, London: Cassell, p. 32

- "Hinter dem eisernen Vorhang", Signal (in German), no. 9, p. 2, May 1943

- Goebbels, Joseph (25 February 1945), "Das Jahr 2000", Das Reich (in German), pp. 1–2

- "Krosigk's Cry of Woe", The Times, p. 4, 3 May 1945

- Churchill, Winston S. (1962), "15", The Second World War, Triumph and Tragedy, vol. 2, Bantam, pp. 489, 514

- Foreign Relations of the US, The Conference of Berlin (Potsdam), vol. 1, US Dept of State, 1945, p. 9

- Churchill 1962, p. 92.

- Debate on the address, vol. 413, Hansard, House of Commons, 16 August 1945, column 84

- Shirer 1990, pp. 515–540.

- Shirer 1990, p. 668.

- Ericson 1999, p. 57.

- Day, Alan J.; East, Roger; Thomas, Richard. A Political and Economic Dictionary of Eastern Europe, p. 405.

- "Stalin offered troops to stop Hitler". London: NDTV. Press Trust of India. 19 October 2008. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- Ericson 1999, pp. 1–210.

- Shirer 1990, pp. 598–610.

- Alperovitz, Gar (1985) [1965], Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam: The Use of the Atomic Bomb and the American Confrontation with Soviet Power, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-008337-8

- Antony Beevor Berlin: The building of the Berlin Wall, p. 80

- Churchill, Winston (5 March 1946). "The Sinews of Peace ('Iron Curtain Speech')". Winstonchurchill.org. International Churchill Society. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "철의 장막: 지식백과" (in Korean). Terms.naver.com. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "철의 장막: 지식백과" (in Korean). Terms.naver.com. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- Stalin. "Interview to "Pravda" Correspondent Concerning Mr. Winston Churchill's Speech". Marxists.org. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Zhdanov: On Literature, Music and Philosophy". revolutionarydemocracy.org.

- Wettig 2008, p. 21

- Senn, Alfred Erich, Lithuania 1940: Revolution from Above, Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007 ISBN 978-90-420-2225-6

- Roberts 2006, p. 43

- Kennedy-Pipe, Caroline, Stalin's Cold War, New York: Manchester University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-7190-4201-1

- Roberts 2006, p. 55.

- Shirer 1990, p. 794.

- Wettig 2008, pp. 96–100

- Granville, Johanna, The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956, Texas A&M University Press, 2004. ISBN 1-58544-298-4

- Grenville 2005, pp. 370–71

- Cook 2001, p. 17

- Beschloss 2003, p. 277

- Miller 2000, p. 16

- Marshall, George C, The Marshal Plan Speech, 5 June 1947

- Miller 2000, p. 10

- Miller 2000, p. 11

- Airbridge to Berlin, "Eye of the Storm" chapter

- Miller 2000, p. 19

- Henig 2005, p. 67

- Department of State 1948, p. preface

- Roberts 2002, p. 97

- Department of State 1948, p. 78

- Department of State 1948, pp. 32–77

- Churchill 1953, pp. 512–524

- Roberts 2002, p. 96

- Miller 2000, pp. 25–31

- Miller 2000, pp. 6–7

- Hornberger, Jacob (1995). "Repatriation – The Dark Side of World War II". The Future of Freedom Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012.

- Nikolai Tolstoy (1977). The Secret Betrayal. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 360. ISBN 0-684-15635-0.

- Böcker 1998, p. 207

- Böcker 1998, p. 209

- Krasnov 1985, pp. 1&126

- Keeling, Drew (2014), business-of-migration.com "Berlin Wall and Migration," Migration as a travel business

- Imrich, Jozef. (2005). Cold river: the cold truth of freedom. East Markham, Ontario: Double Dragon. ISBN 9781554043118. OCLC 225346736.

- Lois Labrianidis, The impact of the Greek military surveillance zone on the Greek side of the Bulgarian-Greek borderlands, 1999

- "The Iron Curtain Trail". Ironcurtaintrail.eu. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Crampton 1997, p. 338

- E. Szafarz, "The Legal Framework for Political Cooperation in Europe" in The Changing Political Structure of Europe: Aspects of International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-1379-8. p.221.

- Ungarn als Vorreiter beim Grenzabbau, orf.at, 2019-06-27.

- Andreas Rödder: Deutschland einig Vaterland – Die Geschichte der Wiedervereinigung (2009), p 72.

- Miklós Németh in Interview with Peter Bognar, Grenzöffnung 1989: "Es gab keinen Protest aus Moskau" (German - Border opening in 1989: There was no protest from Moscow), in: Die Presse 18 August 2014.

- Crampton 1997, p. 392

- Cavanaugh-O'Keefe, John (January 2001), Emmanuel, Solidarity: God's Act, Our Response (ebook), Xlibris Corporation, p. 68, ISBN 0-7388-3864-0, retrieved 6 July 2006

- Steger, Manfred B. (January 2004), Judging Nonviolence: The Dispute Between Realists and Idealists (ebook), Routledge (UK), p. 114, ISBN 0-415-93397-8, retrieved 6 July 2006

- Kenney, Padraic (2002), A Carnival of Revolution: Central Europe 1989, Princeton University Press, p. 15, ISBN 978-0-691-11627-3, retrieved 17 January 2007

- Padraic Kenney, Rebuilding Poland: Workers and Communists, 1945 – 1950, Cornell University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8014-3287-1, Google Print, p.4

- Padraic Kenney (2002), A Carnival of Revolution: Central Europe 1989, Princeton University Press, pp. p.2, ISBN 0-691-05028-7

- Miklós Németh in Interview, Austrian TV - ORF "Report", 25 June 2019.

- Hilde Szabo: Die Berliner Mauer begann im Burgenland zu bröckeln (The Berlin Wall began to crumble in Burgenland - German), in Wiener Zeitung 16 August 1999; Otmar Lahodynsky: Paneuropäisches Picknick: Die Generalprobe für den Mauerfall (Pan-European picnic: the dress rehearsal for the fall of the Berlin Wall - German), in: Profil 9 August 2014.

- Ludwig Greven "Und dann ging das Tor auf", in Die Zeit, 19 August 2014.

- Otmar Lahodynsky "Eiserner Vorhang: Picknick an der Grenze" (Iron curtain: picnic at the border - German), in Profil 13 June 2019.

- Thomas Roser: DDR-Massenflucht: Ein Picknick hebt die Welt aus den Angeln (German - Mass exodus of the GDR: A picnic clears the world) in: Die Presse 16 August 2018.

- "Der 19. August 1989 war ein Test für Gorbatschows" (German - 19 August 1989 was a test for Gorbachev), in: FAZ 19 August 2009.

- Michael Frank: Paneuropäisches Picknick – Mit dem Picknickkorb in die Freiheit (German: Pan-European picnic - With the picnic basket to freedom), in: Süddeutsche Zeitung 17 May 2010.

- Andreas Rödder, Deutschland einig Vaterland – Die Geschichte der Wiedervereinigung (2009).

- Crampton 1997, pp. 394–5

- Crampton 1997, pp. 395–6

- Crampton 1997, p. 398

- Crampton 1997, p. 400

- M. E. Murphy; Rear Admiral; U. S. Navy. "The History of Guantanamo Bay 1494 – 1964: Chapter 18, "Introduction of Part II, 1953 – 1964"". Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- "The Hemisphere: Yankees Besieged". Time. 16 March 1962. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- Wöndu, Steven; Lesch, Ann Mosely (2000). Battle for Peace in Sudan: An Analysis of the Abuja Conferences, 1992-1993. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America (Rowman & Littlefield). p. vii. ISBN 0761815163.

Bibliography

- Beschloss, Michael R (2003), The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-7432-6085-6

- Böcker, Anita (1998), Regulation of Migration: International Experiences, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 90-5589-095-2

- Churchill, Winston (1953), The Second World War, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 0-395-41056-8

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001), Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-8153-4057-5

- Crampton, R. J. (1997), Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century and after, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-16422-2

- Eckert, Astrid M. (2019) West Germany and the Iron Curtain. Environment, Economy, and Culture in the Borderlands. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197582312

- Ericson, Edward E. (1999), Feeding the German Eagle: Soviet Economic Aid to Nazi Germany, 1933–1941, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-96337-3

- Grenville, John Ashley Soames (2005), A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-28954-8

- Grenville, John Ashley Soames; Wasserstein, Bernard (2001), The Major International Treaties of the Twentieth Century: A History and Guide with Texts, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-23798-X

- Henig, Ruth Beatrice (2005), The Origins of the Second World War, 1933–41, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-33262-1

- Krasnov, Vladislav (1985), Soviet Defectors: The KGB Wanted List, Hoover Press, ISBN 0-8179-8231-0

- Miller, Roger Gene (2000), To Save a City: The Berlin Airlift, 1948–1949, Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0-89096-967-1

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2006), Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-11204-1

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2002), Stalin, the Pact with Nazi Germany, and the Origins of Postwar Soviet Diplomatic Historiography, vol. 4.

- Shirer, William L. (1990), The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-671-72868-7

- Soviet Information Bureau (1948), Falsifiers of History (Historical Survey), Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 272848

- Department of State (1948), Nazi-Soviet Relations, 1939–1941: Documents from the Archives of The German Foreign Office, Department of State

- Watry, David M. (2014), Diplomacy at the Brink: Eisenhower, Churchill, and Eden in the Cold War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Wettig, Gerhard (2008), Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7425-5542-6

External links

- Freedom Without Walls: German Missions in the United States—Looking Back at the Fall of the Berlin Wall – official homepage in English

- Information about the Iron Curtain with a detailed map and how to make it by bike

- "Peep under the Iron Curtain", a cartoon first published on 6 March 1946 in the Daily Mail

- Field research along the northern sections of the former German-German border, with detailed maps, diagrams, and photos

- The Lost Border: Photographs of the Iron Curtain

- S-175 "Gardina (The Curtain)"—Main type of electronic security barrier on the Soviet borders (in Russian)

- Remnants of the Iron Curtain along the Greek-Bulgarian border, the Iron Curtain's Southernmost part

- Iron Curtain at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- The Berlin Wall: A Secret History at History Today

- Historic film footage of Winston Churchill's "Iron Curtain" speech (from "Sinews of Peace" address) at Westminster College, 1946

- DIE NARBE DEUTSCHLAND—A 16-hour-long experimental single shot documentary showing the former Iron Curtain running through Germany in its entirety from above, 2008–2014

- [303] "On This Day: Berlin Wall falls"; [304] "Untangling 5 myths about the Berlin Wall". Chicago Tribune. 31 October 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014; [305] "In Photos: 25 years ago today the Berlin Wall Fell". TheJournal.i.e. 9 November 2014.