Kaliningrad Oblast

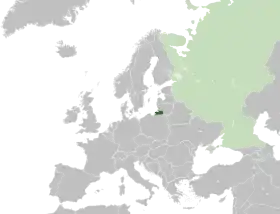

Kaliningrad Oblast (Russian: Калинингра́дская о́бласть, romanized: Kaliningradskaya oblast') is the westernmost federal subject of Russia. It is a semi-exclave situated on the Baltic Sea. The largest city and administrative centre of the province (oblast) is the city of Kaliningrad, formerly known as Königsberg. The port city of Baltiysk is Russia's only port on the Baltic Sea that remains ice-free in winter. Kaliningrad Oblast had a population of roughly 1 million in the Russian Census of 2010.[6]

Kaliningrad Oblast | |

|---|---|

| Калининградская область | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Anthem: Anthem of Kaliningrad Oblast | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Coordinates: 54°48′N 21°25′E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal district | Northwestern[1] |

| Economic region | Kaliningrad[2] |

| Administrative center | Kaliningrad |

| Government | |

| • Body | Legislative Assembly[3] |

| • Governor[4] | Anton Alikhanov |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15,100 km2 (5,800 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 76th |

| Population (2010 Census)[6] | |

| • Total | 941,873 |

| • Estimate (2018)[7] | 994,599 (+5.6%) |

| • Rank | 56th |

| • Density | 62/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 77.6% |

| • Rural | 22.4% |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (MSK–1 |

| ISO 3166 code | RU-KGD |

| License plates | 39, 91 |

| OKTMO ID | 27000000 |

| Official languages | Russian[9] |

| Website | http://www.gov39.ru |

The oblast is bordered by Poland to the south, Lithuania to the north and east, and the Baltic Sea to the north-west. The territory was formerly the northern part of the Prussian province of East Prussia; the remaining southern part of the province is today part of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship in Poland. With the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II, the territory was annexed to the Russian SFSR by the Soviet Union. Following the post-war migration and flight and expulsion of Germans, the territory was populated with mostly Russians.

History

The territory of what is now the Kaliningrad Oblast used to be inhabited by the Old Prussians and other Western Balts, prior to the Teutonic conquest in the early Late Middle Ages.[10] The Old Prussians became extinct due to Germanisation in the first half of the 18th century.[11] The Lithuanian-inhabited areas of the Teutonic State were known as Lithuania Minor, which encompassed all of modern Kaliningrad Oblast until the 18th century.[11]

Late Middle Ages

In the 13th century, the Teutonic Order conquered the region and established a monastic state.[12] In 1255, on the foundations of a destroyed Sambian settlement known as Tvanksta, the Teutonic Order founded the city of Königsberg (modern Kaliningrad), naming it in honour of Ottokar II of Bohemia.[13]

The Northern Crusades, including the Lithuanian Crusade, were partly motivated by colonization.[14] The German colonist peasants, craftsmen and merchants were predominantly concentrated in the southern part of the Teutonic State and did not move into Nadruvia and Skalvia due to the Lithuanian military threat.[14]

15th century

After Poland's victory in the Thirteen Years' War (1454–1466) with the Second Peace of Thorn, the State of the Teutonic Order became a vassal of the Kingdom of Poland.[11] During this war, the capital of the Teutonic state was moved from Marienburg (now Malbork) to Königsberg in 1457.[11] Following the war, Royal Prussia was established on part of the Teutonic Order's territory.[15] When the rulers of the Duchy of Prussia were vassals of the King of Poland, which was the case from 1466 to 1660, there were few German colonists.[11]

History of Brandenburg and Prussia | ||||

| Northern March 965 – 983 |

Old Prussians pre – 13th century | |||

| Lutician federation 983 – 12th century | ||||

| Margraviate of Brandenburg 1157 – 1618 (1806) (HRE) (Bohemia 1373 – 1415) |

Teutonic Order 1224 – 1525 (Polish fief 1466 – 1525) | |||

| Duchy of Prussia 1525 – 1618 (1701) (Polish fief 1525 – 1657) |

Royal (Polish) Prussia (Poland) 1454/1466 – 1772 | |||

| Brandenburg-Prussia 1618 – 1701 | ||||

| Kingdom in Prussia 1701 – 1772 | ||||

| Kingdom of Prussia 1772 – 1918 | ||||

| Free State of Prussia (Germany) 1918 – 1947 |

Klaipėda Region (Lithuania) 1920 – 1939 / 1945 – present |

Recovered Territories (Poland) 1918/1945 – present | ||

| Brandenburg (Germany) 1947 – 1952 / 1990 – present |

Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia) 1945 – present | |||

16th century

After the Teutonic Order lost the war of 1519–1521 with Poland, the Teutonic Order remained a vassal of the Kingdom of Poland.[16] In 1525, Grand Master Albert of Brandenburg secularized the Teutonic Order's Prussian branch and established himself as ruler of the Duchy of Prussia. Königsberg was the residence of the Duke of Prussia from 1525 until 1701.[13] It was the Duchy of Prussia's capital until 1660, when the capital moved to Berlin[13] The Duchy of Prussia was the first Protestant state in Europe.[16]

In 1577, the Duke of Prussia forbade serfs, who were mostly Old Prussians, Lithuanians, Masurians, to leave the land that was the property of the German knights who became proprietary nobles.[17]

17th century

In 1618, the Duchy merged with the Margraviate of Brandenburg into Brandenburg-Prussia.[10]

18th century

During the Seven Years' War it was occupied by the Russian Empire. The region was reorganized into the Province of East Prussia within the Kingdom of Prussia in 1773. The territory of the Kaliningrad Oblast lies in the northern part of East Prussia. The territory was briefly occupied and annexed by Russia in 1758 during the Seven years War before being returned to Prussia in 1762 when Russia switched sides in the war.[18]

Napoleonic occupation

After the defeats of Jena–Auerstedt, the Kingdom of Prussia was invaded and Berlin was occupied by the French. The Court of Prussia fled to Königsberg, asking for Russian help. Russia interfered and this led to the bloody battle of Eylau and battle of Friedland in 1807. The French won and signed the Treaties of Tilsit.[18]

Historical ethnic and religious structure

In 1817, East Prussia had 796,204 Protestants, 120,123 Roman Catholics, 2,389 Jews, and 864 Mennonites.[19]

In 1824, shortly before its merger with West Prussia, the population of East Prussia was 1,080,000 people.[20] According to Karl Andree, Germans were slightly more than half of the people, while 280,000 (~26%) were ethnically Polish and 200,000 (~19%) were ethnically Lithuanian.[21] As of 1819 there were also 20,000 strong ethnic Curonian and Latvian minorities as well as 2,400 Jews, according to Georg Hassel.[22] Similar numbers are given by August von Haxthausen in his 1839 book, with a breakdown by county.[23] However, the majority of East Prussian Polish and Lithuanian inhabitants were Lutherans, not Roman Catholics like their ethnic kinsmen across the border in the Russian Empire. Only in Southern Warmia (German: Ermland) Catholic Poles – so called Warmians (not to be confused with predominantly Protestant Masurians) – comprised the majority of population, numbering 26,067 people (~81%) in county Allenstein (Polish: Olsztyn) in 1837.[23] Another minority in 19th-century East Prussia, were ethnically Russian Old Believers, also known as Philipponnen – their main town was Eckersdorf (Wojnowo).[24][25][26]

German culture and Germanization

East Prussia was an important centre of German culture. Many important figures, such as Immanuel Kant and E. T. A. Hoffmann, came from this region. Despite being heavily damaged during World War II and thereafter, the oblast's cities still contain examples of German architecture. The Jugendstil style showcases the rich German history and cultural importance of the area.

By the early 20th century, Lithuanians formed a majority only in rural parts of north-eastern East Prussia (Memelland and Prussian Lithuania). The same was true of the Latvian-speaking Kursenieki who had settled the coast of East Prussia between Gdańsk and Klaipėda. The rest of the area, except the Polish Masurians in Mazury (southern Prussia), was overwhelmingly German-speaking.

The Memel Territory (Klaipėda region), formerly part of north-eastern East Prussia as well as Prussian Lithuania, was annexed by Lithuania in 1923. In 1938, Nazi Germany radically renamed about a third of the place names of this area, replacing Old Prussian and Lithuanian names with newly invented German names.

Historical Prussian Lithuania comprises a sizeable part of the Prussian region that is now the Kaliningrad Oblast.

Historical Prussian Lithuania comprises a sizeable part of the Prussian region that is now the Kaliningrad Oblast. The Curonian spit in 1649, inhabited by the Kursenieki

The Curonian spit in 1649, inhabited by the Kursenieki The East Prussian resort town of Cranz (Zelenogradsk today) as it looked ca. 1900. It was a destination for German artists and intelligentsia.

The East Prussian resort town of Cranz (Zelenogradsk today) as it looked ca. 1900. It was a destination for German artists and intelligentsia.

World War I

In September 1914, after hostilities began between Germany on the one hand and France and Russia on the other, the Reich was about to seize Paris, and the French urged Russia to attack East Prussia. Nicholas II launched a major attack, resulting in a Russian victory in the Battle of Gumbinnen. The Russian army arrived at the outskirts of the city of Königsberg but did not take it and settled at Insterburg. This Russian victory and East Prussia's occupation by Russia saved Paris by forcing the Germans to send many troops to their East provinces.[27] Later Hindenburg and Ludendorff pushed Russia back at the battle of Tannenberg, thereby liberating East Prussia from Russian troops. Yet Russian troops remained in the easternmost part of the region until early 1915.[28]

World War II

On 29 August 1944, Soviet troops reached the border of East Prussia. By January 1945, they had taken all of East Prussia except for the area around Königsberg. Many inhabitants fled west at this time. During the war's last days, over two million people fled before the Red Army and were evacuated by sea.

Soviet period

Under the terms of the Potsdam Agreement on 1 August 1945, the city became part of the Soviet Union pending the final determination of territorial questions at an anticipated peace settlement. This final determination eventually took place on 12 September 1990 when the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany was signed. The excerpt from the initial agreement pertaining to the partition of East Prussia including the area surrounding Königsberg is as follows (note that Königsberg is spelt "Koenigsberg" in the original document):

VI. CITY OF KOENIGSBERG AND THE ADJACENT AREA

The Conference examined a proposal by the Soviet Government that pending the final determination of territorial questions at the peace settlement, the section of the western frontier of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics which is adjacent to the Baltic Sea should pass from a point on the eastern shore of the Bay of Danzig to the east, north of Braunsberg – Goldep, to the meeting point of the frontiers of Lithuania, the Polish Republic and East Prussia.The Conference has agreed in principle to the proposal of the Soviet Government concerning the ultimate transfer to the Soviet Union of the city of Koenigsberg and the area adjacent to it as described above, subject to expert examination of the actual frontier.

The President of the United States and the British Prime Minister supported the proposal of the Conference at the forthcoming peace settlement.[29]

Königsberg was renamed Kaliningrad in 1946 in memory of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR Mikhail Kalinin. Some historians speculate that it may have originally been offered to the [Lithuanian SSR] because the resolution from the conference specifies that Kaliningrad's border would be at the (pre-war) Lithuanian frontier. The remaining German population was forcibly expelled between 1947 and 1948. The annexed territory was populated with Soviet citizens, mostly ethnic Russians but to a lesser extent also Ukrainians and Belarusians.[30]

The German language was replaced with the Russian language. In 1950, there were 1,165,000 inhabitants, which was only half the number of the pre-war population.

The city was rebuilt after WWII. The territory became strategically important as the Soviet Baltic Fleet's headquarters, as the port is ice-free in winter unlike Saint Petersburg (then Leningrad). Hence, the city was closed to foreign visitors.

The reconstruction of the Oblast, threatened by hunger in the immediate post-war years, was carried out through an ambitious and efficient policy of oceanic fishing[31] with the creation of one of the main fishing harbours of the USSR in Kaliningrad city. Fishing not only fed the regional economy but also was a basis for social and scientific development, in particular oceanography.[32] The region remained ocean-oriented until 1990.[33]

In 1957, an agreement was signed and later came into force which delimited the border between Poland and the Soviet Union.[34][35]

The region was added as a semi-exclave to the Russian SFSR; since 1946 it has been known as the Kaliningrad Oblast. According to some historians, Stalin created it as an oblast separate from the Lithuanian SSR because it further separated the Baltic states from the West.[36] Others think that the reason was that the region was far too strategic for the USSR to leave it in the hands of another SSR other than the Russian one.[32] The names of the cities, towns, rivers and other geographical features were changed to Russian names.

The area was administered by the planning committee of the Lithuanian SSR, although it had its own Communist Party committee. In the 1950s, Nikita Khrushchev offered the entire Kaliningrad Oblast to the Lithuanian SSR but Antanas Sniečkus refused to annex the territory because it would add at least a million ethnic Russians to Lithuania.[30][37]

In 2010, the German magazine Der Spiegel published a report claiming that Kaliningrad had been offered to Germany in 1990 (against payment). The offer was not seriously considered by the West German government which, at the time, saw reunification with East Germany as a higher priority.[38] However, this story was later denied by Mikhail Gorbachev.[39]

Current status

Kaliningrad's isolation was exacerbated by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 when Lithuania became an independent country and even more when both Poland and Lithuania became members of NATO and subsequently the European Union in 2004. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the independence of the Baltic states, Kaliningrad Oblast has been separated from the rest of Russia by other countries instead of by other former Soviet republics. Neighboring nations imposed strict border controls when they joined the European Union. All military and civilian land links between the region and the rest of Russia have to pass through members of NATO and the EU. Russian proposals for visa-free travel between the EU and Kaliningrad have so far been rejected by the EU. Travel arrangements, based on the Facilitated Transit Document (FTD) and Facilitated Rail Transit Document (FRTD)[40][41] have been made.[40][41] On 12 January 1996, Kaliningrad Oblast, alongside Sverdlovsk, became the first oblasts of Russia to sign a power-sharing treaty with the federal government, granting it autonomy.[42] However this agreement was abolished on 31 May 2002.[43]

The territory's economic situation was badly affected by its geographic isolation and the significant reduction in the size of the Russian military garrison, which had previously been one of the major employers and helped the local economy.

After 1991, some ethnic Germans immigrated to the area, such as Volga Germans from other parts of Russia and Kazakhstan, especially after Germany raised the requirements for people from the former Soviet Union to be accepted as ethnic Germans and have a "right of return".

These Germans are overwhelmingly Russian-speaking and as such were rejected for resettlement within Germany under Germany's new rules. A similar migration by Poles from the lands of the former Soviet Union to the Kaliningrad Oblast occurred at this time as well. The situation has begun to change, albeit slowly. Germany, Lithuania, and Poland have renewed contact with Kaliningrad Oblast, through town twinning and other projects. This has helped to promote interest in the history and culture of the East Prussian and Lietuvininkai communities.

In July 2007, Russian First Deputy Prime Minister Sergei Ivanov declared that if US-controlled missile defense systems were deployed in Poland, then nuclear weapons might be deployed in Kaliningrad. On 5 November 2008, Russian president Dmitry Medvedev said that installing missiles in Kaliningrad was almost a certainty.[44] These plans were suspended in January 2009,[45] but implemented in October 2016.[46] In 2011, a long range Voronezh radar was commissioned to monitor missile launches within about 6,000 km (3,700 mi). It is situated in the settlement of Pionersky in Kaliningrad Oblast.[47]

A few months after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Lithuania started implementing EU sanctions, which blocked about 50% of the goods being imported into Kaliningrad by rail, not including food, medicine, or passenger travel. Russia protested the sanctions and announced it would increase shipments by sea.[48][49]

Geography

Kaliningrad is the only Russian Baltic Sea port that is ice-free all year round and hence plays an important role in the maintenance of the country's Baltic Fleet. As a semi-exclave of Russia, it is surrounded by Poland (Pomeranian and Warmian-Masurian Voivodeships), Lithuania (Klaipėda, Marijampolė and Tauragė Counties) and the Baltic Sea. Its largest river is the Pregolya. It starts as a confluence of the Instruch and the Angrapa and drains into the Baltic Sea through the Vistula Lagoon. Its length under the name of Pregolya is 123 km (76 mi), 292 km (181 mi), including the Angrapa.

Notable geographical features include:

- Curonian Lagoon (shared with Lithuania)

- Vistula Lagoon (shared with Poland)

Major cities and towns:

| Russian | German † | Lithuanian † | Polish † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baltiysk | Балтийск | Pillau | Piliava | Piława |

| Chernyakhovsk | Черняховск | Insterburg | Įsrutis | Wystruć |

| Gusev | Гусев | Gumbinnen | Gumbinė | Gąbin |

| Kaliningrad | Калининград | Königsberg | Karaliaučius | Królewiec |

| Sovetsk | Советск | Tilsit | Tilžė | Tylża |

| Svetly | Све́тлый | Zimmerbude | Cimerbūdė | Buda |

† Pre-1946 (the German-language names were also used in English in this period)

Politics

The current governor (since 2017) of Kaliningrad Oblast is Anton Alikhanov. The latest elections to the region's legislative body, the 40-seat Kaliningrad Oblast Duma, were held in September 2016.

Demographics

Settlements

| Largest cities or towns in Kaliningrad Oblast

2021 Russian Census | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Administrative Division | Pop. | Image |

| Kaliningrad | City of oblast significance of Kaliningrad | 498,260 |  |

| Chernyakhovsk | Chernyakhovsky District | 39,126 |  |

| Sovetsk | Town of oblast significance of Sovetsk | 38,514 |  |

| Baltiysk | Baltiysky District | 33,946 |  |

| Gusev, Kaliningrad OblastGusev | Gusevsky District | 28,177 | |

| Svetly, Kaliningrad OblastSvetly | Svetly, Kaliningrad OblastTown of oblast significance of Svetly | 21,441 | |

| Guryevsk, Kaliningrad OblastGuryevsk | Guryevsky District, Kaliningrad OblastGuryevsky District | 19,670 | |

| Zelenogradsk | Zelenogradsky District | 17,296 | |

| Svetlogorsk, Kaliningrad OblastSvetlogorsk | Svetlogorsky District | 16,099 | |

| Gvardeysk | Gvardeysky District | 13,353 | |

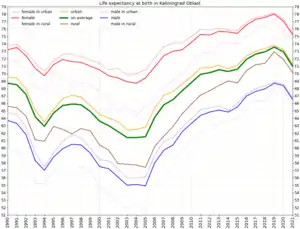

Population

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

At the 2021 census, the population of the oblast was 1,027,678;[6] above of 955,281 recorded in the 2002 census.[50] The 1989 census recorded 871,283 inhabitants.[51]

Ethnic groups

According to the 2010 census, the ethnic composition of the oblast was as follows:[6]

- 772,534 Russians (86.4%)

- 32,771 Ukrainians (3.7%)

- 32,497 Belarusians (3.6%)

- 9,769 Lithuanians (1.1%)

- 9,226 Armenians (1%)

- 7,349 Germans (0.8%)

- 4,534 Tatars (0.5%)

- 3,282 Azeris (0.4%)

- 2,788 Poles (0.3%)

- 2,245 Uzbeks (0.3%)

- 16,857 others (1.9%)

- 48,021 people were registered from administrative databases and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group.[52]

| Census[53] | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 2002 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russians | 473,861 (77.6%) | 564,469 (77.1%) | 632,717 (78.3%) | 683,563 (78.5%) | 786,885 (82.4%) | 772,534 (86.4%) |

| Ukrainians | 35,717 (5.8%) | 48 044 (6.6%) | 54,656 (6.8%) | 62,750 (7.2%) | 47,229 (4.9%) | 32,771 (3.7%) |

| Belarusians | 57,178 (9.4%) | 68,808 (9.4%) | 72,465 (9.0%) | 73,926 (8.5%) | 50,748 (5.3%) | 32,497 (3.6%) |

| Lithuanians | 21,262 (3.5%) | 23,376 (3.2%) | 19,647 (2.4%) | 18,116 (2.1%) | 13,937 (1.5%) | 9,769 (1.1%) |

Total fertility rate [54]

| Year | Rate |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 1.11 |

| 2005 | 1.16 |

| 2010 | 1.46 |

| 2013 | 1.64 |

| 2014 | 1.70 |

| 2015 | 1.75 |

| 2016 | 1.73 |

| 2017 | 1.57 |

Religion

According to a 2012 survey[55] 34% of the population of Kaliningrad Oblast declare themselves to be "spiritual but not religious", 30.9% adhere to the Russian Orthodox Church, 22% are atheist and 11.1% follow other religions or did not give an answer to the question, 1% are unaffiliated generic Christians and 1% adhere to the Catholic Church.[55]

Until 1945, the region was overwhelmingly Lutheran, with a small number of Catholics and Jews. The state church of Prussia was dominant in the region. Although it was both Reformed and Lutheran since 1817, there was an overwhelming Lutheran majority and very few Reformed adherents in East Prussia.

Economy

In 2020, the GRP of Kaliningrad Oblast was around €9 billion total and €9,000 per capita.[57]

The oblast derives an economic advantage from its geographic position as an ice-free port and its proximity to the European Union. It also has the world's largest deposits of amber. The region has developed its tourism infrastructure and promotes attractions such as the Curonian Spit.[58]

To address the oblast's high rate of unemployment, in 1996 the Russian authorities granted the oblast a special economic status with tax incentives that were intended to attract investors. The oblast's economy has since benefited substantially and in recent years experienced a boom. A US$45 million airport terminal has been opened and the European Commission provides funds for business projects under its special program for the region. Trade with the countries of the EU has increased. Economic output has increased.[59]

According to official statistics, the Gross Regional Product in 2006 was 115 billion roubles.[60] GRP per capita in 2007 was 155 669 roubles.[61]

Industry

Car and truck assembly (GM, BMW, Kia, Yuejin by Avtotor) and the production of auto parts are major industries in Kaliningrad Oblast. There are shipbuilding facilities in Kaliningrad and Sovetsk. Food processing is a mature industry in the region with Miratorg operating a sizeable food processing factory. OKB Fakel, a world leader in the field of Hall thruster development, as well as a leading Russian developer and manufacturer of electric propulsion systems, is based in Neman. The company employs 960 people.[62][63] General Satellite (GS) is the biggest employer in Gusev city, producing satellite receivers, cardboard packaging, nanomaterials etc.

Natural resources

Kaliningrad Oblast possesses more than 90% of the world's known amber deposits.[64] Until recently raw amber was exported for processing to other countries, but in 2013 the Russian government banned the export of raw amber in order to boost the amber processing industry in Russia.[65]

There are small oil reservoirs beneath the Baltic Sea not far from Kaliningrad's shore. Small-scale offshore exploration started in 2004. Poland, Lithuania, and some local NGOs, voiced concerns about possible environmental effects.

Fishing

Fishing is an important regional industry, with big fishing ports in Kaliningrad and Pionersky and smaller ones in Svetly and Rybachy.

Power generation

Average yearly power consumption in the Kaliningrad Oblast was 3.5 terawatt-hours in 2004 with local power generation providing just 0.235 terawatt-hours. The balance of energy needs was imported from neighbouring countries. A new Kaliningrad power station was built in 2005, covering 50% of the oblast's energy needs. A second part to this station was built in 2010, making the oblast independent from electricity imports.

In 2008, planning began for the construction of two nuclear power reactors, with costs estimated at €5 billion (US$8 billion).[66] The project was suspended in May 2013, and in 2014, it was abandoned after environmental concerns and lack of support.[67]

Agriculture

Yli-Mattila et al., 2009 finds that all Fusarium graminearum populations here are 3ADON, common also to Finland and Saint Petersburg.[68] They speculate that this may be due to a shared population in this area which is distinct from other F. graminearum populations.[68]

See also

- Kaliningrad Special Region

- List of rural localities in Kaliningrad Oblast

References

Citations

- Президент Российской Федерации. Указ №849 от 13 мая 2000 г. «О полномочном представителе Президента Российской Федерации в федеральном округе». Вступил в силу 13 мая 2000 г. Опубликован: "Собрание законодательства РФ", No. 20, ст. 2112, 15 мая 2000 г. (President of the Russian Federation. Decree #849 of May 13, 2000 On the Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Russian Federation in a Federal District. Effective as of May 13, 2000.).

- Госстандарт Российской Федерации. №ОК 024-95 27 декабря 1995 г. «Общероссийский классификатор экономических регионов. 2. Экономические районы», в ред. Изменения №5/2001 ОКЭР. (Gosstandart of the Russian Federation. #OK 024-95 December 27, 1995 Russian Classification of Economic Regions. 2. Economic Regions, as amended by the Amendment #5/2001 OKER. ).

- Charter of Kaliningrad Oblast, Article 17

- Charter of Kaliningrad Oblast, Article 28

- Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (21 May 2004). "Территория, число районов, населённых пунктов и сельских администраций по субъектам Российской Федерации (Territory, Number of Districts, Inhabited Localities, and Rural Administration by Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation)". Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). 3 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Official throughout the Russian Federation according to Article 68.1 of the Constitution of Russia.

- Matulevičius, Algirdas. "Prūsija" [Prussia]. VLE (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Matulevičius, Algirdas; Kaunas, Domas. "Mažoji Lietuva" [Lithuania Minor]. VLE (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Gudavičius, Edvardas. "Vokiečių ordinas" [German Order]. VLE (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Matulevičius, Algirdas; Purvinas, Martynas. "Karaliaučiaus istorija". VLE (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Jasas, Rimantas; Kairiūkštytė, Nastazija; Matulevičius, Algirdas. "kolonizacija". VLE (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Matulevičius, Algirdas. "Karališkoji Prūsija" [Royal Prussia]. VLE (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Matulevičius, Algirdas. "Albrechtas Brandenburgietis". VLE (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Matulevičius, Algirdas. "Prūsijos kunigaikštystė" [Duchy of Prussia]. VLE (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Roqueplo O: La Russie et son Miroir...2018

- Hoffmann, Johann Gottfried (1818). Übersicht der Bodenfläche und Bevölkerung des Preußischen Staates : aus den für das Jahr 1817 mtlich eingezogenen Nachrichten. Berlin: Decker. p. 51.

- Plater, Stanisław (1825). Jeografia wschodniéy części Europy czyli Opis krajów przez wielorakie narody słowiańskie zamieszkanych: obejmujący Prussy, Xsięztwo Poznańskie, Szląsk Pruski, Gallicyą, Rzeczpospolitę Krakowską, Krolestwo Polskie i Litwę (in Polish). Wrocław: u Wilhelma Bogumiła Korna. p. 17.

- Andree, Karl (1831). Polen: in geographischer, geschichtlicher und culturhistorischer Hinsicht (in German). Verlag von Ludwig Schumann. p. 218.

- Hassel, Georg (1823). Statistischer Umriß der sämmtlichen europäischen und der vornehmsten außereuropäischen Staaten, in Hinsicht ihrer Entwickelung, Größe, Volksmenge, Finanz- und Militärverfassung, tabellarisch dargestellt; Erster Heft: Welcher die beiden großen Mächte Österreich und Preußen und den Deutschen Staatenbund darstellt (in German). Verlag des Geographischen Instituts Weimar. p. 41.

- Haxthausen, August (1839). Die Ländliche Verfassung in den Einzelnen Provinzen der Preussischen Monarchie (in German). pp. 75–91.

- "Monastery of the Dormition of the Mother of God in Wojnowo (Eckersdorf)". wojnowo.net.

- Tetzner, Franz (1902). Die Slawen in Deutschland: beiträge zur volkskunde der Preussen, Litauer und Letten, der Masuren und Philipponen, der Tschechen, Mährer und Sorben, Polaben und Slowinzen, Kaschuben und Polen. Braunschweig: Verlag von F. Vieweg. pp. 212–248.

- "Old Believers in Poland - historical and cultural information". Poland's Linguistic Heritage. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- Roqueplo O: La Russie et son Miroir..., 2018

- Roqueplo O: La Russie et son miroir...2018

- "The Potsdam Declaration". Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- Milan Bufon (11 April 2014). The New European Frontiers: Social and Spatial (Re)Integration Issues in Multicultural and Border Regions. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 98. ISBN 978-1443859363.

- Roqueplo O: La Russie et son Miroir d'Extrême-Occident, Langues'O, HAL, 2018

- Roqueplo O: La Russie et son miroir d'Extrême-Occident, 2018

- Roqueplo O: La Russie et son Miroir d'Extrême-Occident, 2018

- "Russia (USSR) / Poland Treaty (with annexed maps) concerning the Demarcation of the Existing Soviet–Polish State Frontier in the Sector Adjoining the Baltic Sea 5 March 1957" (PDF). Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- For other issues of the frontier delimitation see "Maritime boundary delimitation agreements and other material". Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. (2005). Visions of Victory: The hopes of eight World War II leaders. Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-521-85254-8.

- Krickus, Richard J. (2002). "2. Kaliningrad under Soviet and Russian Rule". The Kaliningrad Question. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 39. ISBN 9780742517059 – via Google Books.

- Wiegrefe, Klaus (22 May 2010). Müller von Blumencron, Mathias; Mascolo, Georg (eds.). "Zeitgeschichte: Historischer Ballast" [Contemporary History: Historical Ballast]. Der Spiegel (in German). Hamburg, Germany: Spiegel-Berlag. ISSN 2195-1349. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017.

- Berger, Stefan (31 July 2010). Rusbridger, Alan (ed.). "Should Kant's home once again be German?". The Guardian. London, England, United Kingdom. ISSN 1756-3224. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021.

- "Transit from/to Kaliningrad Region, www.euro.lt". Archived from the original on 1 November 2009.

- eur-lex.europa.eu http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2003:099:0008:0008:EN:PDF.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Solnick, Steven (29 May 1996). "Asymmetries in Russian Federation Bargaining" (PDF). The National Council for Soviet and East European Research: 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- Chuman, Mizuki. "The Rise and Fall of Power-Sharing Treaties Between Center and Regions in Post-Soviet Russia" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya: 146. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ""Medvedev Says Russia to Deploy Missiles Near Poland" Associated Press via Yahoo News".

- Harding, Luke (28 January 2009). "Russia scraps plan to deploy nuclear-capable missiles in Kaliningrad". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Russia moves missiles to Kaliningrad". BBC News. 9 October 2016.

- Sudakov, Dmitry (28 November 2011). "Russia's new radar to monitor all Europe including Britain". Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- A Russian enclave in Europe is the latest source of Ukraine war tensions

- Inside Kaliningrad, Russian exclave at the centre of Ukraine war sanctions row

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (21 May 2004). Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- "ВПН-2010". www.perepis-2010.ru. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- "Приложение Демоскопа Weekly". www.demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011.

- "Age-specific fertility rates (Ru:Возрастные коэффициенты рождаемости)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia". Sreda, 2012.

- 2012 Arena Atlas Religion Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27 August 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2017. Archived.

- "Валовой региональный продукт по субъектам Российской Федерации в 2016-2020гг".

- "Kaliningrad Region – Introduction". Russia: All Regions Trade & Investment Guide. CTEC Publishing LLC. 2008.

- "Regions and territories: Kaliningrad". BBC News. 15 May 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- Regional administration's website (Russian) Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Валовой региональный продукт на душу населения Федеральная служба государственной статистики

- "EDB Fakel". OKB Fakel. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "OKB Fakel (Russian Federation)". Jane's Space Systems and Industry. 17 December 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- How Products Are Made: Amber Archived 11 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "The History of Russian Amber, Part 2: From USSR to Russia" Archived 15 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Leta.st

- "Kaliningrad plan for Baltic States market". World Nuclear News. 17 April 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- Prak, Caroline (24 April 2014). "Victoire ! Le projet de centrale nucléaire à Kaliningrad est enterré". Les Amis de la Terre (in French). Retrieved 31 May 2021.

-

- Yli-Mattila, Tapani; Gagkaeva, Tatiana; Ward, Todd J.; Aoki, Takayuki; Kistler, H. Corby; O’Donnell, Kerry (2009). "A novel Asian clade within the Fusarium graminearum species complex includes a newly discovered cereal head blight pathogen from the Russian Far East". Mycologia. Mycological Society of America (T&F). 101 (6): 841–852. doi:10.3852/08-217. ISSN 0027-5514. PMID 19927749. S2CID 1898391. S2CID 87676141. S2CID 199369505. (TYM ORCID: 0000-0002-0336-880X).

- Pasquali, Matias; Beyer, Marco; Logrieco, Antonio; Audenaert, Kris; Balmas, Virgilio; Basler, Ryan; Boutigny, Anne-Laure; Chrpová, Jana; Czembor, Elżbieta; Gagkaeva, Tatiana; González-Jaén, María T.; Hofgaard, Ingerd S.; Köycü, Nagehan D.; Hoffmann, Lucien; Lević, Jelena; Marin, Patricia; Miedaner, Thomas; Migheli, Quirico; Moretti, Antonio; Müller, Marina E. H.; Munaut, Françoise; Parikka, Päivi; Pallez-Barthel, Marine; Piec, Jonathan; Scauflaire, Jonathan; Scherm, Barbara; Stanković, Slavica; Thrane, Ulf; Uhlig, Silvio; Vanheule, Adriaan; Yli-Mattila, Tapani; Vogelgsang, Susanne (6 April 2016). "A European Database of Fusarium graminearum and F. culmorum Trichothecene Genotypes". Frontiers in Microbiology. Frontiers. 7: 406. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00406. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 4821861. PMID 27092107. S2CID 1866403.

- Lamichhane, Jay Ram; Venturi, Vittorio (27 May 2015). "Synergisms between microbial pathogens in plant disease complexes: a growing trend". Frontiers in Plant Science. Frontiers. 06: 385. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00385. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 4445244. PMID 26074945. S2CID 11132230.

- van der Lee, Theo; Zhang, Hao; van Diepeningen, Anne; Waalwijk, Cees (8 January 2015). "Biogeography of Fusarium graminearum species complex and chemotypes: a review". Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A. International Society for Mycotoxicology (TF). 32 (4): 453–460. doi:10.1080/19440049.2014.984244. ISSN 1944-0049. PMC 4376211. PMID 25530109. S2CID 14678133.

General and cited sources

- Roqueplo O: La Russie & son Miroir d'Extrême-Occident, Langues'O, HAL, 2018

- Областная Дума Калининградской области. Закон №30 от 18 января 1996 г. «О вступлении в действие Устава (Основного Закона) Калининградской области», в ред. Закона №483 от 2 декабря 2015 г «О внесении изменения в Устав (Основной Закон) Калининградской области». Вступил в силу по истечении десяти дней со дня официального публикования, за исключением пункта 5 статьи 15 и подпункта "б" статьи 22 в части подписания постановлений областной Думы председателем областной Думы, которые введены в действие одновременно со вступлением в силу Федерального закона от 06.10.1999 №184-ФЗ "Об общих принципах организации законодательных (представительных) и исполнительных органов государственной власти субъектов Российской Федерации". Опубликован: "Янтарный край", №20, 26 января 1996 г. (Oblast Duma of Kaliningrad Oblast. Law #30 of January 18, 1996 On the Charter (Basic Law) of Kaliningrad Oblast Taking Effect, as amended by the Law #483 of December 2, 2015 On Amending the Charter (Basic Law) of Kaliningrad Oblast. Effective as of the date ten days after the official publication date, with the exception of item 5 of Article 15 and the portion of subitem "b" of Article 22 dealing with the signing of the resolutions of the Oblast Duma by the Chair of the Oblast Duma, which take effect simultaneously with the Federal Law #184-FZ of October 6, 1999 "On the General Principles of the Organization of the Legislative (Representative) and Executive Organs of the State Power in the Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation".).

- Калининградская областная Дума. Закон №463 от 27 мая 2010 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Калининградской области», в ред. Закона №450 от 3 июля 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Калининградской области "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Калининградской области"». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Калининградская правда" (вкладыш "Ведомости Правительства Калининградской области"), №112, 26 июня 2010 г. (Kaliningrad Oblast Duma. Law #463 of May 27, 2010 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Kaliningrad Oblast, as amended by the Law #450 of July 3, 2015 On Amending the Law of Kaliningrad Oblast "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Kaliningrad Oblast". Effective as of the day of the official publication.).

- Simon Grunau, Preußische Chronik. Hrsg. von M. Perlbach etc., Leipzig, 1875.

- A. Bezzenberger, Geographie von Preußen, Gotha, 1959

- Областная Дума Калининградской области. Закон №30 от 18 января 1996 г. «О вступлении в действие Устава (Основного Закона) Калининградской области», в ред. Закона №483 от 2 декабря 2015 г «О внесении изменения в Устав (Основной Закон) Калининградской области». Вступил в силу по истечении десяти дней со дня официального публикования, за исключением пункта 5 статьи 15 и подпункта "б" статьи 22 в части подписания постановлений областной Думы председателем областной Думы, которые введены в действие одновременно со вступлением в силу Федерального закона от 06.10.1999 №184-ФЗ "Об общих принципах организации законодательных (представительных) и исполнительных органов государственной власти субъектов Российской Федерации". Опубликован: "Янтарный край", №20, 26 января 1996 г. (Oblast Duma of Kaliningrad Oblast. Law #30 of January 18, 1996 On the Charter (Basic Law) of Kaliningrad Oblast Taking Effect, as amended by the Law #483 of December 2, 2015 On Amending the Charter (Basic Law) of Kaliningrad Oblast. Effective as of the date ten days after the official publication date, with the exception of item 5 of Article 15 and the portion of subitem "b" of Article 22 dealing with the signing of the resolutions of the Oblast Duma by the Chair of the Oblast Duma, which take effect simultaneously with the Federal Law #184-FZ of October 6, 1999 "On the General Principles of the Organization of the Legislative (Representative) and Executive Organs of the State Power in the Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation".).

External links

- Official website of Kaliningrad Oblast (in Russian)

- A. Liucija Arbusauskaité "The Soviet Policy Towards the 'Kaliningrad Germans' 1945–1951" chapter in Themenheft: Eingliederung und Ausgrenzung. Beiträge aus der Historischen Migrationsforschung. Hrsg.: Jochen Oltmer Osnabrück: IMIS, 1999. ISSN 0949-4723

- Master's thesis by Sergey Naumkin on the possibility of Kaliningrad integrating with the EU as a special economic zone

- Life in Kaliningrad Oblast (in Russian)

- Spuren der Vergangenheit / Следы Пρошлого (Traces of the Past) This site by W. A. Milowskij, a Kaliningrad resident, contains hundreds of interesting photos, often with text explanations, of architectural and infrastructural artifacts of the territory's long German past. (in German and Russian)

- City and Reagen News