Republic of Karelia

The Republic of Karelia (Russian: Респу́блика Каре́лия, romanized: Respublika Kareliya; Russian pronunciation: [rʲɪˈspublʲɪkə kɐˈrʲelʲɪ(j)ə]; Karelian: Karjalan tašavalta; Livvi: Karjalan tazavaldu; Finnish: Karjalan tasavalta; Veps: Karjalan Tazovaldkund, Ludic: Kard’alan tazavald), also known as just Karelia (Russian: Каре́лия, Ка́рьяла; Karelian: Karjala),[11] is a republic of Russia situated in Northwest Russia.[11] The republic is a part of the Northwestern Federal District, and covers an area of 172,400 square kilometres (66,600 square miles), with a population of 603,067 residents.[12] Its capital is Petrozavodsk.

Republic of Karelia | |

|---|---|

| Республика Карелия | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Finnish | Karjalan tasavalta |

| • Livvi | Karjalan tazavaldu |

| • Karelian Proper | Karjalan tašavalta |

| • Vepsian | Karjalan tazovaldkund |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Anthem: Anthem of the Republic of Karelia | |

| |

| Coordinates: 63°49′N 33°00′E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal district | Northwestern[1] |

| Economic region | Northern[2] |

| Capital | Petrozavodsk |

| Government | |

| • Body | Legislative Assembly[3] |

| • Head[4] | Artur Parfenchikov[5] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 172,400 km2 (66,600 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 20th |

| Population (2010 Census)[7] | |

| • Total | 643,548 |

| • Estimate (2018)[8] | 622,484 (−3.3%) |

| • Rank | 68th |

| • Density | 3.7/km2 (9.7/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 78.0% |

| • Rural | 22.0% |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| ISO 3166 code | RU-KR |

| License plates | 10 |

| OKTMO ID | 86000000 |

| Official languages | Russian[10] |

| Website | http://www.gov.karelia.ru |

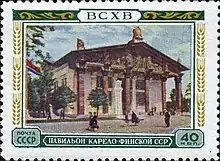

The modern Karelian Republic was founded as an autonomous republic within the Russian SFSR by the Resolution of the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK) on 27 June 1923 and by the Decree of the VTsIK and the Council of People's Commissars of 25 July 1923, from the Karelian Labour Commune. From 1940 to 1956, it was known as the Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic, one of the union republics in the Soviet Union. In 1956, it was once again made an autonomous republic and remained part of Russia following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Etymology

"Karelia" derives from the name of the ethnic group—Karelians. The name "Karjala" has unknown origins,however, it is theorised that it may come from the Proto-Finnish word karja, meaning "herd", which was borrowed from the Proto-Germanic harjaz ("army"); the ending -la means "earth".[13]

Geography

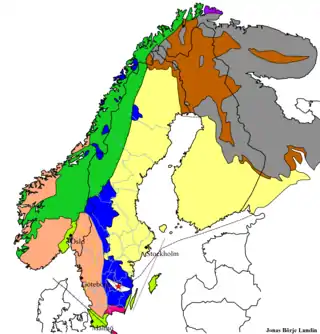

The republic is in the northwestern part of Russia, between the White and Baltic Seas. The White Sea has a shoreline of 630 kilometers (390 mi). It has an area of 172,400 km2 (66,600 sq mi). It shares internal borders with Murmansk Oblast (north), Arkhangelsk Oblast (east/south-east), Vologda Oblast (south-east/south), and Leningrad Oblast (south/south-west), and it also borders Finland (Kainuu, Lapland, North Karelia, Northern Ostrobothnia, and South Karelia); the borders measure 723 km. The main bodies of water next to Karelia are the White Sea (an inlet of the Barents Sea) to the north-east and Lake Onega and Lake Ladoga both shared with neighboring Oblasts to the south. Its highest point is the Nuorunen peak at 576 m (1,890 ft).

Geology

As a part of the Fennoscandian Shield's ancient Karelian craton, most of the Republic of Karelia's surficial geology is Archaean or Paleoproterozoic, dated up to 3.4 billion years in the Vodlozero block. This area is the largest contiguous Archaean outcrop in Europe and one of the largest in the world.

Since deglaciation, the rate of post-glacial rebound in the Republic of Karelia has varied. Since the White Sea connected to the World's oceans uplift along the southern coast of Kandalaksha Gulf has totaled 90 m. In the interval 9,500–5,000 years ago the uplift rate was 9–13 mm/yr. Before the Atlantic period, uplift rate had decreased to 5–5.5 mm/yr, to then rise briefly before arriving at the present uplift rate is 4 mm/yr.[14]

Rivers

There are about 27,000 rivers in Karelia. Major rivers include:

- Vodla River (Vodlajoki, 149 km)

- Kem River (Kemijoki, 191 km)

- Kovda River (Koutajoki)

- Shuya River (Šuojogi)

- Suna River (Suunujoki) with Kivach Falls (Kivatšun vesiputous)

- Vyg River (Uikujoki)

Lakes

There are 60,000 lakes in Karelia. The republic's lakes and swamps contain about 2,000 km³ of high-quality fresh water. Lake Ladoga (Finnish: Laatokka) and Lake Onega (Ääninen) are the largest lakes in Europe. Other lakes include:

- Nyukozero (Nuokkijärvi)

- Pyaozero (Pääjärvi)

- Segozero (Seesjärvi)

- Syamozero (Säämäjärvi)

- Topozero (Tuoppajärvi)

- Vygozero (Uikujärvi)

The lakes Ladoga and Onega are located in the south of the republic.

Islands

White Sea coast:

- Oleniy Island

- Chernetskiye Island

- Kamestrov Island

- Kuzova Archipelago

- Shuy Island

- Kutulda Island

- Perkhludy Island

- Lesnaya Osinka Island

- Kotkano Island

- Vygnvolok Island

- Tumishche Island

- Sum Island

- Razostrov Island

- Sedostrov Island

- Myagostrov Island

- Zhuzhmuy Islands

- Kondostrov Island

In Lake Onega:

- Bolshoy Klimenetsky Island

In Lake Ladoga:

- Vossinoysari Island

Heinäsenmaa island

Heinäsenmaa island - Valaam Island

- Mantsinsaari Island

- Lunkulansaari Island

National parks

- Vodlozero National Park

- Kalevala National Park

- Paanajärvi National Park

Natural resources

The majority of the republic's territory (148,000 km2 (57,000 sq mi), or 85%) is composed of state forest stock. The total growing stock of timber resources in the forests of all categories and ages is 807 million m³. The mature and over-mature tree stock amounts to 411.8 million m³, of which 375.2 million m³ is coniferous.

Fifty useful minerals are found in Karelia, located in more than 400 deposits and ore-bearing layers. Natural resources of the republic include iron ore, diamonds, vanadium, molybdenum, and others.

Climate

The Republic of Karelia is located in the Atlantic continental climate zone. The average temperature in January is −8.0 °C (17.6 °F) and +16.4 °C (61.5 °F) in July. Average annual precipitation is 500–700 mm.[15]

Administrative divisions

Administrative and territorial division:16 districts (including 3 national districts), 2 city okrugs. 21 urban settlements, 85 rural settlements (including 3 Vepsian rural settlements).[16][17][18]

History

Middle ages

The Karelian people and culture developed during the Viking Age in the region to the west of Lake Ladoga. Karelians were first mentioned in Swedish sagas around the 10th century. Russians first mentioned Karelians in 1143, they called Karelians "Korela".[19]

Sweden's interest in Karelia began a centuries-long struggle with Novgorod (later Russia) that resulted in numerous border changes following the many wars fought between the two, the most famous of which is the Pillage of Sigtuna of 1187. In 1137 the oldest documented settlement was established, the modern-day city of Olonets (Aunus).[20] Karelians converted to Orthodox Christianity in 1227.[21] The Karelians' alliance with Novgorod developed into domination by the latter in the 13th century, when Karelia became a part of Novgorod under the name of Obonezhie pyatina as an autonomy. Later Karelia had anti-Novgorod revolts in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Later Karelia became a part of Muscovy when Novgorod was annexed in the second half of the 15th century.

During the Great Northern War (1700-1712) the modern-day capital of Karelia, the city of Petrozavodsk was founded as a cannon factory by Peter the Great.[22]

19th century

On September 9(21) 1801 Olonets Governorate was created by order of Alexander I.[23]

Early 20th century

In 1906 the Union of White Sea Karelians (Vienan karjalaisten liito) was created, it advicated for equal rights for minorities and democratization.[24] It stopped existing in 1911 after its leaders were deported to Siberia. It later influenced Karelian intelligentsia which led to the creation of the Uhtua Republic.

In 1918 White Karelia declared independence from Russia, creating the Uhtua Republic. In 1920 Finnish forces in the south occupied Olonets, creating a puppet government, which was crushed by the Red Army in the same year. The Republic of Uhtua was crushed in December 1920.

Soviet Karelia

On June 8, 1920 Karelian Labour Commune was created. In 1921 an insurrection was started as a last attempt to restore the Uhtua Republic, but it was crushed by the Red Army, many Karelian, Finnish, and some Russian families left for Finland with only some returning to Soviet Karelia, they were later repressed under Stalin.[25] In 1923, the KLC became the Karelian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Karelian ASSR).

In the 1930s Finnish communists, who fled to Karelia, were purged. People of Finnish and Karelian nationality were also subject to repressions. Despite being 3% of the population, over 41% of all repressed in Karelia were Finns, 27% were Karelian, and 25% were Russian.[26] Karelia has one of the biggest burial sites of Stalinist purges in Russia - Sandarmoh, where possibly thousands of victims were executed.

Winter War

During the Winter War, a Soviet puppet government was created in occupied territories. Finnish Democratic Republic was to incorporate most of Finland's pre-war territories plus some western parts of the KASSR. Some members of the FDP government were also members of the KASSR government.[27]

After the Moscow Peace Treaty territories of the Karelian Isthmus were transferred to the newly created Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic. After the evacuation of Finnish Karelia the new territories were left unpopulated so migrants from Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, and other Soviet republics moved-in. To this day, this area has one of the lowest percentages of Karelian and Finnish populations in the Republic.

World War II

After the beginning of the Great Patriotic war, mass rallies were held on the territory of the republic, at which the inhabitants of Karelia declared their readiness to stand up for the defense of the Soviet Union. Workers of the Onega Tractor Plant wrote “We will work only in such a way as to fully meet the needs of our Red Army. We will double, triple our forces and crush, destroy the German fascists".[28]

On 24 June 1941, after the German army crossed Zapadnaya Dvina, Finnish president Risto Ryti announced declaration of war on the Soviet Union.[28] The Finnish army crossed the Soviet border on 1 July.[29]

Soon after the evacuation of border regions began, On July 3, a republican evacuation commission was created. At its first meeting, it was decided to evacuate children under 14 out of Petrozavodsk. The same decision also refers to the evacuation of 150 families of leading party and Soviet workers in Karelia. Those residents who could work had to remain in the harvest and defense work.[30]

By September the Finnish army already reached Petrozavodsk and captured Olonets.[29] Petrozavodsk offensive began on 20 September. To protect the city, the 7th Army under the command of General K.A. Meretskov was directly subordinated to the Headquarters of the Supreme Commander.[31]

On September 30, the position of the defenders of the city deteriorated sharply. The Finnish army managed to break through Soviet defenses and cut the highway to Kondopoga in the area of the Sulazhgorsky brick factory. In the south Finns came close to the city outskirts. On October 1, due to the threat of encirclement, an order was received from the command to withdraw the main units defending the city.

The fighting near Petrozavodsk allowed the authorities to evacuate most of the civilian population and a significant part of the production capacities. In total, more than 500 thousand people were evacuated from the republic to the east. Petrozavodsk University was temporarily relocated to Syktyvkar.[29]

After the capture of Petrozavodsk, the capital of Soviet Karelia was transferred first to Medvezhyegorsk, then to Belomorsk. Less than 90 thousand people remained in the occupied territory, half of which are representatives of the Finno-Ugric peoples: Karelians, Vepsians, and Finns. The Finnish administration has officially recognized them as a "kindred" population. The rest received the status of "unrelated" people.[29] Most of them have been put into concentration camps, along with communists and people who could not speak Finnish or karelian.

Former prisoners of the camps recalled that the staff often treated them more harshly than was supposed to according to the instructions. According to them, the Finns in the presence of children shot prisoners, and beat women, children, and the elderly. One of the prisoners told the Finnish historian Helga Seppel that before leaving Petrozavodsk, the invaders shot several young people for unknown reasons.[29]

During the occupation, Petrozavodsk was renamed to Äänislinna.

Only a few territories of the KFSSR managed to escape the Finnish occupation: the Belomorsky, Loukhsky, Kemsky, Pudozhsky regions, as well as part of the Medvezhiegorsky, Tungudsky and Ukhta regions. By 1942, about 70 thousand people lived here.[30]

After the end of the Siegie of Leningrad Soviet army was ordered to liberate Karelia.

On the 21st of June, 1944 Svir-Petrozavodsk operation started. On 27 June the Finnish army left Petrozavodsk. By August the Soviet army reached pre-war borders.

Post-war

After the end of WW2 the Karelian Isthmus was incorporated into the Leningrad Oblast and the city of Alakurtti was transferred to Murmansk oblast.

After normalization of diplomatic relations between USSR and Finland the status of the Karelo-Finnish SSR was changed back to the Karelian ASSR in 1956. After this Karelian, Veps, and Finnish languages began a decline in usage due to the lack of any support from the state and lack of education.[32]

The transformation of the KFSSR into the Karelian ASSR was supposed to show that the USSR did not have aggressive goals against Finland.[33]

In 1978 Korean airlines Boeing 707-321B was shot down over Murmansk oblast and landed near Louhi.

Present-day

In August 1990 KASSR declared its sovereignty as an autonomus part of the Russian Federation.[34] And later changed its name to the Republic of Karelia in 1991.

In 2004 Veps National Volost was transferred to Prionezhsky District.

In 2006 a racial conflict and later riot started in Kondopoga after a fight between locals and Caucasian immigrants led to 2 deaths.[35] This caused an exodus of Muslims from Karelia.

In 2011 a plane crashed near the village of Besovets killing 47 people.

Politics

The highest executive authority in the Republic of Karelia is the Head of the Republic. The acting Head of the Republic is Artur Parfenchikov, who was elected in February 2017 and later re-elected in 2022.

The parliament of the Republic of Karelia is the Legislative Assembly comprising fifty deputies elected for a four-year term.

The Constitution of the Republic of Karelia was adopted on 12 February 2001.

Demographics

Population: 643,548 (2010 Census);[7] 645,205 (2002 Census);[36] 791,317 (1989 Census).[37]

Settlements

Largest cities or towns in the Republic of Karelia 2010 Russian Census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Administrative Division | Pop. | |||||||

Petrozavodsk  Kondopoga |

1 | Petrozavodsk | Prionezhsky District | 261,987 |  Segezha  Kostomuksha | ||||

| 2 | Kondopoga | Kondopozhsky District | 32,987 | ||||||

| 3 | Segezha | Segezhsky District | 29,631 | ||||||

| 4 | Kostomuksha | Town of republic significance of Kostomuksha | 28,436 | ||||||

| 5 | Sortavala | Town of republic significance of Sortavala | 19,235 | ||||||

| 6 | Medvezhyegorsk | Medvezhyegorsky District | 15,533 | ||||||

| 7 | Kem | Kemsky District | 13,051 | ||||||

| 8 | Pitkyaranta | Pitkyarantsky District | 11,429 | ||||||

| 9 | Belomorsk | Belomorsky District | 11,217 | ||||||

| 10 | Suoyarvi | Suoyarvsky District | 9,766 | ||||||

Vital statistics

| Average population (×1,000) | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1,000) | Crude death rate (per 1,000) | Natural change (per 1,000) | Fertility rates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 714 | 11,346 | 5,333 | 6,013 | 15.9 | 7.5 | 8.4 | |

| 1975 | 723 | 12,748 | 6,086 | 6,662 | 17.6 | 8.4 | 9.2 | |

| 1980 | 741 | 12,275 | 7,374 | 4,901 | 16.6 | 10.0 | 6.6 | |

| 1985 | 770 | 13,201 | 8,205 | 4,996 | 17.1 | 10.7 | 6.5 | |

| 1990 | 792 | 10,553 | 8,072 | 2,481 | 13.3 | 10.2 | 3.1 | 1.87 |

| 1991 | 790 | 8,982 | 8,305 | 677 | 11.4 | 10.5 | 0.9 | 1.62 |

| 1992 | 788 | 7,969 | 9,834 | −1,865 | 10.1 | 12.5 | −2.4 | 1.46 |

| 1993 | 782 | 7,003 | 11,817 | −4,814 | 9.0 | 15.1 | −6.2 | 1.30 |

| 1994 | 774 | 6,800 | 13,325 | −6,525 | 8.8 | 17.2 | −8.4 | 1.26 |

| 1995 | 767 | 6,729 | 12,845 | −6,116 | 8.8 | 16.7 | −8.0 | 1.24 |

| 1996 | 760 | 6,461 | 11,192 | −4,731 | 8.5 | 14.7 | −6.2 | 1.19 |

| 1997 | 753 | 6,230 | 10,306 | −4,076 | 8.3 | 13.7 | −5.4 | 1.15 |

| 1998 | 747 | 6,382 | 10,285 | −3,903 | 8.5 | 13.8 | −5.2 | 1.18 |

| 1999 | 740 | 6,054 | 11,612 | −5,558 | 8.2 | 15.7 | −7.5 | 1.12 |

| 2000 | 732 | 6,374 | 12,083 | −5,709 | 8.7 | 16.5 | −7.8 | 1.18 |

| 2001 | 725 | 6,833 | 12,597 | −5,764 | 9.4 | 17.4 | −7.9 | 1.25 |

| 2002 | 717 | 7,247 | 13,435 | −6,188 | 10.1 | 18.7 | −8.6 | 1.33 |

| 2003 | 707 | 7,290 | 14,141 | −6,851 | 10.3 | 20.0 | −9.7 | 1.32 |

| 2004 | 696 | 7,320 | 13,092 | −5,772 | 10.5 | 18.8 | −8.3 | 1.31 |

| 2005 | 686 | 6,952 | 12,649 | −5,697 | 10.1 | 18.4 | −8.3 | 1.24 |

| 2006 | 676 | 6,938 | 11,716 | −4,778 | 10.3 | 17.3 | −7.1 | 1.22 |

| 2007 | 667 | 7,319 | 11,007 | −3,688 | 11.0 | 16.5 | −5.5 | 1.28 |

| 2008 | 659 | 7,682 | 11,134 | −3,452 | 11.7 | 16.9 | −5.2 | 1.35 |

| 2009 | 651 | 7,884 | 10,599 | −2,715 | 12.1 | 16.3 | −4.2 | 1.58 |

| 2010 | 644 | 7,821 | 10,471 | −2,650 | 12.1 | 16.2 | −4.1 | 1.58 |

| 2011 | 641 | 7,711 | 9,479 | −1,768 | 12.0 | 14.7 | −2.7 | 1.60 |

| 2012 | 640 | 8,027 | 9,804 | −1,777 | 12.6 | 15.4 | −2.8 | 1.71 |

| 2013 | 636 | 7,553 | 9,285 | −1,732 | 11.9 | 14.6 | −2.7 | 1.65 |

| 2014 | 634 | 7,816 | 9,245 | −1,429 | 12.3 | 14.6 | −2.3 | 1.74 |

| 2015 | 631 | 7,731 | 9,648 | −1,917 | 12.2 | 15.3 | −3.1 | 1.76(e) |

Ethnic groups

According to the 2010 Census,[7] ethnic Russians make up 82.2% of the republic's population, ethnic Karelians 7.4%. Other groups include Belarusians (3.8%), Ukrainians (2%), Finns (1.4%), Vepsians (0.5%), and a host of smaller groups, each accounting for less than 0.5% of the total population.

| Ethnic group |

1926 census | 1939 census | 1959 census | 1970 census | 1979 census | 1989 census | 2002 census | 2010 census1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Russians | 153,967 | 57.2% | 296,529 | 63.2% | 412,773 | 62.7% | 486,198 | 68.1% | 522,230 | 71.3% | 581,571 | 73.6% | 548,941 | 76.6% | 507,654 | 82.2% |

| Karelians | 100,781 | 37.4% | 108,571 | 23.2% | 85,473 | 13.0% | 84,180 | 11.8% | 81,274 | 11.1% | 78,928 | 10.0% | 65,651 | 9.2% | 45,570 | 7.4% |

| Belarusians | 555 | 0.2% | 4,263 | 0.9% | 71,900 | 10.9% | 66,410 | 9.3% | 59,394 | 8.1% | 55,530 | 7.0% | 37,681 | 5.3% | 23,345 | 3.8% |

| Ukrainians | 708 | 0.3% | 21,112 | 4.5% | 23,569 | 3.6% | 27,440 | 3.8% | 23,765 | 3.2% | 28,242 | 3.6% | 19,248 | 2.7% | 12,677 | 2.0% |

| Finns | 2,544 | 0.9% | 8,322 | 1.8% | 27,829 | 4.2% | 22,174 | 3.1% | 20,099 | 2.7% | 18,420 | 2.3% | 14,156 | 2.0% | 8,577 | 1.4% |

| Vepsians | 8,587 | 3.2% | 9,392 | 2.0% | 7,179 | 1.1% | 6,323 | 0.9% | 5,864 | 0.8% | 5,954 | 0.8% | 4,870 | 0.7% | 3,423 | 0.5% |

| Others | 2,194 | 0.8% | 20,709 | 4.4% | 29,869 | 4.5% | 20,726 | 2.9% | 19,565 | 2.7% | 21,505 | 2.7% | 25,734 | 3.6% | 16,422 | 2.7% |

| 1 25,880 people were registered from administrative databases, and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group.[38] | ||||||||||||||||

Languages

Currently Russian is the only official language of the republic. Karelian, Veps, and Finnish have been officially recognized languages of the republic since 2004, and they are de-jure are supported by the government.[39] In early 2000s Karelian and Veps language nests were created in Petrozavodsk, Kalevala, Tuksa and Sheltozero,[40] but were later shut down.[41] Now native languages of Karelia have little support from the government.[32] Finnish was the second official language of Karelia from the creation of the Karelian Labour Commune up until the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[42] Thereafter there were suggestions to raise Karelian as the second official language, but they were repeatedly turned down.[43][39]

Religion

The Karelians have traditionally been Eastern Orthodox. Lutheranism was brought to Karelia during Sweden's conquest of Karelia and was common in regions that then belonged to Finland. Nowadays Lutherans can be found in most big settlements but they remain a minority.[46]

Catholics have one parish in Petrozavodsk.[47]

Petrozavodsk Jewish Religious Community was registered in 1997.[48]

Karelian Muslims were organized into Karelian muftiate in 2001.[49]

According to a 2012 survey,[44] 27% of the population of Karelia adheres to the Russian Orthodox Church, 2% are unaffiliated Christians, and 1% are members of Protestant churches. In addition, 44% of the population declared to be "spiritual but not religious", 18% is atheist, and 8% follow other religions or did not answer the question.[44]

Economy

Karelia's economy is based on forestry, mining, tourism, agriculture, fishing[50] and paper industry.

Despite being 0,4% of Russia's population, 65–70% of all Russian trout is grown in the Republic, 26% of iron ore pellets, 20% of paper, 12% of wood pulp and cellulose.

Karelia's gross regional product (GRP) in 2007 was 109.5 billion rubles.[51] The Karelian economy's GRP in 2010 was estimated at 127733.8 million rubles. Karelia's GRP in 2021 was 176 billion rubles.[50] This amounts to 291,841 rubles per capita, which is lower than national average.

The largest companies in the region include Karelsky Okatysh ($1319755601 of revenue in 2021), Segezha Pulp and Paper Mill ($86897488 of revenue in 2021), OAO Kondopoga ($20366599 of revenue in 2021).[52]

In the structure of the gross regional product in 2017, the main types of economic activity were:mining - 17.6%; manufacturing industries - 16.9%; transportation and storage - 11.8%; wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles - 9.8%; public administration and military security; social security - 8.7%.[53]

A fast fiber-optic cable link connecting Finnish Kuhmo and Karelian Kostomuksha was built in 2007, providing fast telecommunications.[51]

Forestry

The forest and wood processing sector dominates industrial activity in Karelia. A large number of small enterprises carry out timber logging whereas pulp and paper production is concentrated in five large enterprises, which produce about a quarter of Russia's total output of paper.[54] Three largest companies in the pulp and paper sector in 2021 were: OAO Kondopoga (sales of $369314325), Segezha Pulp and Paper Mill ($221317040) and RK-Grand (Pitkäranta Pulp Factory) ($78750849).[52]

The timber industry complex of Karelia produces 28% of the republic's industrial output.[55]

Mining

Karelia is a region with a lot of natural resources, from gold to metals.[56][57]

In 2007, extractive industries (including extraction of metal ores) amounted to 30% of the republic's industrial output.[51] There are about 53 mining companies in Karelia, employing more than 10,000 people.[58] One of the most important companies in the sector is AO Karelian Pellet, which is the 5th largest of Russia's 25 mining and ore dressing enterprises involved in ore extraction and iron ore concentrate production. Other large companies in the sector were OAO Karelnerud, Mosavtorod State Unitary Enterprise, and Pitkjaranta Mining Directorate State Unitary Enterprise.[15]

Energy

.jpg.webp)

As of 2021, there were 29 powerplants, of them 21 were hydroplants and 8 thermal power plants.[59]

Agriculture

Due to Karelia's climate, only 1,2% of the land is used for farming. Most of the farmalnd is located on podzol.[60]

20 agricultural organizations employing 2.3 thousand people. Animal husbandry is the leading branch of agriculture in the Republic, the main areas of which are dairy cattle breeding, pig breeding, broiler poultry farming, and fur farming.[61]

Annually agricultural enterprises of the region produce up to 59 thousand tons of milk. Based on its natural and climatic conditions, the plant growing industry is focused on the production of feed for livestock, the bulk of potatoes and vegetables are grown in small forms of management.[61]

Fishing

Fishing enterprises of Karelia produced 91.9 thousand tons of aquatic biological resources in 2021.

In the Barents Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, 89.9 thousand tons of aquatic biological resources were caught, of them 34.6 thousand tons of cod and haddock, 34.1 thousand tons of blue whiting, 18 thousand tons of mackerel and 1.1 thousand tons of northern shrimp. 306 tons of fish were caught in the White Sea and 612 tons of kelp and fucus were harvested. The catch of freshwater fish amounted to 1.1 thousand tons.[62]

Tourism

Karelia is popular for international and domestic tourism.

Traditional, active, cultural and ecological types of tourism are popular among tourists.[63]

Karelia attracts ecotourists with its nature and wilderness[64] and low population density. During the summer water tourism is also popular among many tourists.

Cultural tourism is also a big part of Karelia's tourism economy. The region attracts many tourists with its wooden architecture, local culture, and traditions.

Karelia also has the first Russian health resort - Martial Waters (1719).

Foreign trade

The economy of Karelia is export-orientated. By the volume of exports per capita, Karelia is among the leading regions of Russia. More than 50% of manufactured products (and up to 100% in several industries) are exported.[50]

The Republic's main export partners in 2001 were Finland (32% of total exports), Germany (7%), Netherlands (7%), and the United Kingdom (6%).[15] Main export products were lumber (over 50%), iron ore pellets (13–15%) paper and cardboard (6–9%) and sawn timber with (5–7%). Many of Karelia's companies have received investments from Finland.[15]

Transportation

Railroad

Karelia is a strategically important railroad region due to the fact that it connects Murmansk with the rest of Russia by Kirov Railway, which was electrified in 2005.[65]

There are also railways connections with Finland in Värtsilä and Kostomuksha, but they are not electrified.

All Karelian district capitals are connected by railroad, except for the Kalevalsky district and Prionezhsky district, which do not have a capital.

In total, Karelia has 1915 km of railways.[66]

Water communications

Water communications connect Karelia with the Barents, Baltic, Black, White and Caspian Seas.

Whitea sea-Baltic Canal was built in the 1930s to connect the Baltic and White seas. The 227 km long canal was built by the prisoners. Even though it has 19 locks, the canal cannot pass vessels with a draft of more than 5 meters.[67] The canal is a part of the Volgo-Baltic Waterway.

There are also river ports on the coast of the White Sea, there were plans to upgrade them to ocean ports but they were deemed too expensive.[68]

Highways

Automobile highway R-21 "Kola" crosses Karelia and connects Murmansk Region and Murmansk seaport with St. Petersburg and Moscow.

E105 European highway also goes thru Karelia.

Other highways connect with Finland in Louhsky district Värtsilä and Kostomuksha.

Many of Karelian roads are still unimproved.[69]

Culture

Karelia is very culturally diverse region that was influenced by Finno-Ugric, Slavic and Scandinavian cultures.

Literature

Karelia is sometimes called "the songlands", as Karelian poems constitute most of the Karelo-Finnish epic Kalevala and many of Russian Bylinas were documented in Pudozh.[72]

The written literature of Karelia was formed at the beginning of the 20th century. In the 1930s Karelian and Veps languages gained a writing system, but during the Stalinist repressions many books in veps and Karelian were burned and cultural figures were deported.[73]

After the creation of the Karelian Labour Commune many American and Canadian finns moved to Karelia and began creating new literature. Many Karelians could understand Finnish so some authors, such as one of the most famous Karelian writers Antti Timonen, started to write in Finnish.[74]

Art

Karelian art history begun with Petroglyphs, which were created around 6,500 years ago.[75] They became a UNESCO World Heritage Site, listed in 2021.[76]

Icon painters were the first professional artists of Karelia.[77]

Karelia has become a source of inspiration for many famous artists of the 19th-20th century such as: Ivan Shishkin, Arkhip Kuindzhi, and N. K. Roerich.

_%D0%9D%D0%B0_%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B5_%D0%B4%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BC.jpg.webp) Ivan Shishkin, In the wild north... (1891)

Ivan Shishkin, In the wild north... (1891) Arkhip Kuindzhi, Ladoga (1873)

Arkhip Kuindzhi, Ladoga (1873).jpg.webp) N. K. Roerich Pomors. Evening (1907)

N. K. Roerich Pomors. Evening (1907)

Architecture

Karelia is famous for its wooden architecture. Karelian architecture developed under the strong influence of Novgorod architecture.[78] Examples of Karelian architecture are collected in the Kizhi Pogost Museum.

Later Karelian architecture was influenced by Finns, especially after the creation of the Karelian Labour Commune.

Music

Kantele is the most famous traditional Karelian musical instrument. In Kalevala the mage Väinämöinen makes the first kantele from the jawbone of a giant pike and a few hairs from Hiisi's stallion.

In 1939, the Symphony Orchestra of the Karelo-Finnish State Philharmonic was founded.[79]

Throughout the years, many Karelian, Russian, Veps, Finnish and Pomor choirs were created, such as the Karelian choir "Oma pajo" in 1990, which is still active.[80]

Museums

State Historical, Architectural and Ethnographic Museum-Reserve "Kizhi"[81]

National Museum of the Republic of Karelia[82] (including Sheltozero Veps Ethnographic Museum, Museum "Marcial Waters" and Museum of the Karelian Front in Belomorsk[83])[81]

"Valaam Research, Church-Archaeological and Natural Museum-Reserve"

Museum of Fine Arts of the Republic of Karelia[82][84]

Museum of the History of Public Education of the Republic of Karelia

Theaters

Musical Theater of the Republic of Karelia

National Theater of the Republic of Karelia

State Puppet Theater of the Republic of Karelia

Drama Theater of the Republic of Karelia "Creative Workshop"[82]

Non-state author's theater "Ad Liberum"[85]

Musical Theater of the Republic of Karelia

Musical Theater of the Republic of Karelia National Theater of the Republic of Karelia

National Theater of the Republic of Karelia State Puppet Theater of the Republic of Karelia

State Puppet Theater of the Republic of Karelia Drama Theater of the Republic of Karelia "Creative Workshop"

Drama Theater of the Republic of Karelia "Creative Workshop".jpg.webp) Non-state author's theater "Ad Liberum"

Non-state author's theater "Ad Liberum"

Holidays

Along with Russian holidays, Karelia has its official public holidays as well as unofficial holidays.

Official

| Date | Name | Russian name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 18 | Day of firefighters of the Republic of Karelia | День пожарной охраны Республики Карелия | Holiday celebrating Karelian fire defense became official in 1998.[86] |

| May 31 | Day of cultural workers of the Republic of Karelia | День работника культуры Республики Карелия | Holiday celebrating Karelian workers in the culture industry, became official in 2000[87] |

| Summer[88] (Official June 8) | Republic of Karelia day (Republic Day) | День Республики Карелия | Holiday celebrating creation of the Karelian Labour commune, became official in 1999[89] |

| September 16 | Day of formation of the trade union movement in Karelia | День образования профсоюзного движения в Карелии | Holiday celebrating Karelian trade unions and worker's rights, became official in 2011[90] |

| September 30 | Day of the liberation of Karelia from fascist invaders | День освобождения Карелии от фашистских захватчиков | Holiday celebrating liberation from Finnish occupation during WW2[91] |

Religious

| Date | Name | Karelian name | Russian name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 7 to January 18 | Winter religious Holidays | Vierissänkesk, Sv’atkat, Sunduma | Зимние святки | Celebrations after Christmas |

| January 19 | Baptism | Vieristä, Vieristy, Vederis | Крещение | Prelude to Maslenitsa |

| May 6 | Saint George's Day | Jyrin päivä, Jyrrinpäivy, Kevät Jyrgi | Егорьев день | |

| May 22 | Nikola Veshny | Pyhä Miikkula, Miikkulan päivä, Miikkulanpäivy, Mikula | Никола Вешний | Day celebrating Saint Nicholas |

| End of July | Bowl of Ukko | Ukon vakka | Чаша Укко | Ancient pre-Christian agricultural holiday |

| July 7 | Ivan's Day | Iivnanpäivä, Iivananpäivy, Ivananpäivä | Иванов день | Holiday celebrating summer solstice |

| From the end of Ivan's day before Saint Peter's day | Summer religious holidays | Kezäsv’atkat, Kesäsvätkat | Летние святки | Prelude to Saint-Peter's day |

| July 12 | Saint Peter's day | Petrunpäivä, Pedrunpäivy, Pedrunpäivä | Петров день | Celebrations before harvest |

| August 2 | Elijah's day | Il’l’anpäivä, Il’l’anpäiväy | Ильин день | |

| August 31 | Frol's Day | Frolan päivä | Фролов день | Local holidas of livestock protection |

| End of October | Kekri | Kekri, Kegri | Кегри | Ancient autumn festival |

| December 25 | Christmas | Rostuo | Католическое Рождество | Western Christmas is celebrated by Karelian Finns |

| References[92] | ||||

Cultural

| Region | Date | Name | Russian name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All of Karelia | April | Day of Karelian and Vepsian writing | День карельской и вепсской письменности | Cultural holiday of karelians and vepsians[93] |

| February | Kalevala Day | День Калевалы | Day celebrating national epic Kalevala[94] | |

| February | International Mother Language Day | Международный день родного языка | ||

| Autumn | Kegri | Кегри | Gained government support in 2022[95] | |

| Belomorskyi | November | Holiday of Pomors of the Karelian coast "Nikola Zimniy" | Праздник поморов Карельского берега «Никола Зимний» | Pomor holiday |

| Kalevalskyi | June | International holiday of Ukhta Karelians | Международный праздник Ухтинских карел | North Karelian holiday |

| Kemskyi | August | Indian Summer in the Kem Pomorye | Бабье лето в Кемском поморье | Pomor holiday |

| Day of the Dead Poduzhemsky villages | День погибших подужемских деревень | Day remembering abandoned villages of North Karelia | ||

| May | Holiday of men's craft "Oars on the water" | Праздник мужских ремесле «Весла на воду» | ||

| Louhskyi | June | Interregional holiday "Hello, Kestenga!" | Межрегиональный праздник «Здравствуй, Кестеньга!» | North Karelian holiday |

| August | Holiday "Fairytale ship Korguev" | Праздник «Сказочный корабль Коргуева» | Holiyday in Chupa | |

| August | Holiday "Old Woman Louhi's Day" | Праздник «День старухи Лоухи» | Holiday celebrating Kalevala | |

| August | Kanšallenen puku ompelos | Каншалленен пуку омпелуш | Holiday in Sofporog | |

| Muyezerskyi | March | Interdistrict cultural and sports festival "Winter fun" | Межрайонный культурно-спортивный праздник «Зимние забавы» | Holiday in Muyezersky |

| Karelian-Finnish friendship holiday of the village of Ondozero and the village of Yolyolä (Finland) | Карело-финский праздник дружбы села Ондозеро и деревни Ёлёля (Финляндия) | |||

| Olonetskyi | May | Ecological festival "Olonets - goose capital" | Экологический фестиваль «Олония-гусиная столица» | Holiday in Olonets |

| December | Olonets Father Frost Games | Олонецкие Игры Дедов Морозов | Holiyday challening people pretending to be Ded Moroz or Talviukko | |

| Petrozavodsk | February | Международный зимний фестиваль «Гиперборея» | International winter festival "Hyperborea" | Ice sculpture festival[96] |

| Prionezhskyi | Prionezhsky song wreath | Прионежский песенный венок | ||

| Elonpuu (Tree of life) | Древо жизни | Veps holiday[97] | ||

| Pryazhinskyi | March | "Kulyan kižat" | «Кюлян кижат» | Holiday in Vedlozero |

| Holiday of Karelian culture | Праздник карельской культуры | Holiday in Kinerma | ||

| Pudozhskyi | June | Interregional holiday "Dawns of Pudozh" | Межрегиональный праздник «Зори Пудожья» | Holiday in Pudozh |

| June | Holiday of Russian epic culture "In the land of the epic" | Праздник русской эпической культуры «В краю былинной» | Holiday in Semenovo | |

| Segezshky | June | Ethnocultural holiday "Voitsk festivities" | Этнокультурный праздник «Воицкие гуляния» | Holiday in Nadvoitsy |

| References[92] | ||||

See also

- Karelian Isthmus

- Music of Karelia

- Sami music

- Pegrema

References

- Президент Российской Федерации. Указ №849 от 13 мая 2000 г. «О полномочном представителе Президента Российской Федерации в федеральном округе». Вступил в силу 13 мая 2000 г. Опубликован: "Собрание законодательства РФ", No. 20, ст. 2112, 15 мая 2000 г. (President of the Russian Federation. Decree #849 of May 13, 2000 On the Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Russian Federation in a Federal District. Effective as of May 13, 2000.).

- Госстандарт Российской Федерации. №ОК 024-95 27 декабря 1995 г. «Общероссийский классификатор экономических регионов. 2. Экономические районы», в ред. Изменения №5/2001 ОКЭР. (Gosstandart of the Russian Federation. #OK 024-95 December 27, 1995 Russian Classification of Economic Regions. 2. Economic Regions, as amended by the Amendment #5/2001 OKER. ).

- Constitution, Article 32

- Constitution, Article 46.

- Official website of the Republic of Karelia. Artur Olegovich Parfenchikov

- Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (21 May 2004). "Территория, число районов, населённых пунктов и сельских администраций по субъектам Российской Федерации (Territory, Number of Districts, Inhabited Localities, and Rural Administration by Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation)". Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). 3 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Official throughout the Russian Federation according to Article 68.1 of the Constitution of Russia.

- "Karelia". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2022 года". Федеральная служба государственной статистики. 1 January 2022.

- "Karelia". Online Etymology Dictionary. 10 October 2017. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021.

- Romanenko, F.A.; Shilova, O.S. (2011). "The Postglacial Uplift of the Karelian Coast of the White Sea according to Radiocarbon and Diatom Analyses of LacustrineBoggy Deposits of Kindo Peninsula". Doklady Earth Sciences. 442 (2): 544–548. doi:10.1134/S1028334X12020079. S2CID 129656482.

- "Republic of Karelia". Russia: All Regions Trade & Investment Guide. CTEC Publishing LLC. 2003.

- "Закон Республики Карелия от 03.07.2020 № 2483-ЗРК "О преобразовании муниципальных образований "Сортавальское городское поселение" и "Хелюльское городское поселение" Сортавальского муниципального района Республики Карелия и о внесении изменений в отдельные законодательные акты Республики Карелия"". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации. 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020.

- "ЗАКОН РЕСПУБЛИКИ КАРЕЛИЯ от 1 декабря 2004 года N 824-ЗРК". Электронный фонд правовых и нормативно-технических документов. 1 December 2004. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020.

- "ЗАКОН РЕСПУБЛИКИ КАРЕЛИЯ от 1 декабря 2004 года N 825-ЗРК". Электронный фонд правовых и нормативно-технических документов. 1 December 2004. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017.

- "Рождение народа". Кирьяж. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Кочуркина, С.И.; Куспак, Н.В.; Мамонтова, Н.Н.; Платонов, В.Г. (1994). Древний Олонец. Ин-т языка, лит-ры и истории Карельского науч. центра РАН. Петрозаводск. ISBN 9785201077280.

- "Основные исторические даты и события". Карелия Официальная. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- "Петрозаводск". Академик.

- "Эволюция административно-территориального устройства Карелии в XVIII — начале XX века // Ученые записки Петрозаводского государственного университета. Серия: Общественные и гуманитарные науки.2013. февраль. № 1 — С.12-18" (PDF). uchzap.petrsu.ru. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- Левонтьев, П.Р. (2008). "УХТА НА ПЕРЕЛОМЕ ВЕКОВ (УХТИНСКАЯ РЕСПУБЛИКА)". Войница.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Usatševa, J.V. (2021). ITÄ-KARJALAN PAKOLAISET TIE KOTIIN (in Karelian). Petroskoi: Periodika. ISBN 978-5-88170-394-3.

- Takala, Irina (2018). "THE GREAT TERROR IN KARELIA".

- "Павел Степанович Прокконен". Карелия СССР. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Макуров, В.Г. "Карелия в Великой Отечественной войне 1941—1945 гг. Исторический очерк". Объекты историко-культурного наследия Карелии. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Лисаков, Евгений. Лукьянова, Мария (ed.). "Карельский фронт". Республика. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Саввина, Карина. "Война: Карелия 1941-1945 гг". Regnum. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Оборона Петрозаводска. 1941 год". Объекты историко-культурного наследия Карелии. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Yarovoy, Gleb (21 February 2020). ""Вызывайте переводчика". Как коренные народы борются за сохранение языка". Север.Реалии.

- "Общественно-политическая жизнь в республике (часть 2)". Русский Север. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Shtepa, Vadim (8 August 2012). "Забытый День республики". СТОЛИЦА на Онего.

- "Началось оглашение приговора по делу о драке в Кондопоге". РАПСИ. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Russian Federal State Statistics Service (21 May 2004). Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- "ВПН-2010". www.perepis-2010.ru.

- Karelian, Vepps, and Finnish languages have got the state support in the Republic of Karelia The Official Web Portal of the Republic of Karelia (2004)

- "Информация о деятельности языковых гнезд в Карелии и результатах работы финно-угорского Проекта "Языковое гнездо"". Finnoug. 21 November 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2019.

- "Рабочая группа минрегиона РФ похоронила "языковые" гнезда в России". Finugor. 6 March 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2013.

- Karjalan ASNT:n Perustuslaki (in Finnish). Petroskoi: Karjala-Kustantamo. 1980. p. 162.

- Vesti Karelia (14 July 2016). "Государственный статус карельского языка вызвал споры депутатов". YouTube.

- "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia". Sreda, 2012.

- 2012 Arena Atlas Religion Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27/08/2012. Retrieved 21/04/2017. Archived.

- "Карельское пробство". Евангелическо-Лютеранская Церковь Ингрии. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Католики в Карелии". Католики в Карелии. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Иудаизм". КАРЕЛИЯ ОФИЦИАЛЬНАЯ. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013.

- "РОЦЕНТРАЛИЗОВАННАЯ РО ДУХОВНОЕ УПРАВЛЕНИЕ МУСУЛЬМАН РЕСПУБЛИКИ КАРЕЛИЯ (КАРЕЛЬСКИЙ МУХТАСИБАТ)". РБК. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Главное о регионе - Республика Карелия". Оценка регулирующего воздействия (in Russian). Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "The Republic of Karelia in 2007". Helsinki School of Economics.

- "Выписки ЕГРЮЛ и ЕГРИП, проверка контрагентов, ИНН и КПП организаций, реквизиты ИП и ООО". СБИС (in Russian). Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- "Республика Карелия". Инвестиционный портал регионов России. 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Regional characteristics. Republic of Karelia". Helsinki School of Economics.

- Лесной план Республики Карелия. Том 1 (in Russian). 2010.

- "Republic of Karelia, Russia". Mindat. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Matthis, Simon (16 February 2021). "Karelia Republic may become one of centers of mining in Russia in years to come". Mining Metal News. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Mining industry of the republic has summed up its work in the first six months of the year". Republic of Karelia. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- "РАСПОРЯЖЕНИЕ Главы Республики Карелия,Page 53" (PDF). 30 April 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Сельское хозяйство Республики Карелия". Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- "Общая информация о сельском хозяйстве Республики Карелия". Агросоветник. 6 June 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- "Почти 90 тысяч тонн рыбы выловили карельские рыбаки за три квартала этого года". Республика. 8 November 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Karelia". Karelia. Tourism portal. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Karelia Travel Guide". 56 Parallel. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Bennett, Mia (28 October 2015). "The Kirov Railway: A shot of steel through northwest Russia". CRYOPOLITICS. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Fomina, Elena. Lukjanova, Maria (ed.). "Железная дорога". Республика. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Fomina, Elena. Lukjanova, Maria (ed.). "Беломорско-Балтийский канал". Республика. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Bershtein, Maxim (20 August 2018). "Беломорский порт: построить можно – но не ясно, зачем". MKRU. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Leonov, Dmitry (27 August 2019). "Дороги Карелии". Планета Дорог. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Единственный аэропорт Карелии закроется на месяц в октябре". Итерфакс. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Аэропорты Карелии". Аэропорты России. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Novikov, Y. A. (2007). "Об истоках пудожской былинной традиции". Электронная библиотека публикации о музее-заповеднике "Кижи".

- Mishin, Armas (22 March 2007). "Современная культура вепсов". Финно-угорский информационный центр. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

- "Финская национальная литература". Фольклорно-литературное наследие Русского Севера. 23 September 2011. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020.

- Lobanova, Nadezhda. "Karelian Rock Art". Karelia. Tourism portal.

- "Petroglyphs of Lake Onega and the White Sea". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 8 November 2021.

- Plotnikov, V. I. (1958). "Первые профессиональные художники — уроженцы Карелии // Труды карельского филиала Академии наук СССР. Вопросы истории Карелии. Выпуск Х. 1958. С.50-6" (PDF). resources.krc.karelia.ru. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2017.

- Orfinskyi, V. P. (1972). Деревянное зодчество Карелии. Leningrad: Stroyizdat.

- "История". Карельская государственная филармония.

- "Концерт Oma pajo в честь 30-летия". Центр народного творчества и культурных инициатив. 2 March 2021.

- "Museums in Karelia". Karelia. Tourism portal.

- "Государственные, автономные и образовательные учреждения, подведомственные Министерству культуры РК". Карелия официальная. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015.

- Prokhorov, Ilja (20 November 2020). "Музей Карельского фронта". Respublika.

- "The Museum of Fine Arts of Republic of Karelia". russianmuseums.

- "AdLiberum". Vkontakte.

- "Закон Республики Карелия от 5 февраля 1998 г. 258-ЗРК «Об установлении Дня пожарной охраны Республики Карелия»". Законодательное собрание Республики Карелия. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Закон Республики Карелия от 28 сентября 2000 г. 430-ЗРК «Об установлении Дня работника культуры Республики Карелия»". Законодательное собрание Республики Карелия. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "День Республики Карелия 2022: Полная программа". ГТРК Карелия. 26 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Закон Республики Карелия от 27 апреля 1999 г. N 346-ЗРК «Об установлении Дня Республики Карелия»". Законодательное собрание Республики Карелия. Archived from the original on 27 July 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "Об установлении Дня образования профсоюзного движения в Карелии". Карелия Официальная. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Закон Республики Карелия от 21 октября 2011 г. N 1535-ЗРК «Об установлении Дня освобождения Карелии от фашистских захватчиков»". Законодательное собрание Республики Карелия.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Елына, Э.Г. "Традиционные карельские праздники". Центр Народного Творчества и Культурных Инициатив. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Parfenchikov, A.O. "Поздравление Главы Республики Карелия А.О.Парфенчикова с Днем карельской и вепсской письменности". Официальный интернет-портал Республики Карелия. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ""Вселенная Калевала": Карелия и Финляндия отмечают день народного эпоса". RGRU. 28 February 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "О внесении изменений в сводную бюджетную роспись Республики Карелия предусмотрев на 2022 год в целях организации и проведения в 2022 году сельскохозяйственной ярмарки в рамках праздника Урожая-Дня Кегри". Официальный интернет-портал Республики Карелия. 14 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Праздники и события". Карелия туристический портал. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Sidorkin, Valery (17 August 2012). "Шелтозерское древо". Гудок РЖД ТВ. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Sources

- Верховный Совет Карельской АССР. №473-ЗРК 30 мая 1978 г. «Конституция Республики Карелия», в ред. Закона №1314-ЗРК от 16 июля 2009 г «О внесении изменений в Конституцию Республики Карелия». Опубликован: отдельной брошюрой. (Supreme Soviet of the Karelian ASSR. #473-ZRK May 30, 1978 Constitution of the Republic of Karelia, as amended by the Law #1314-ZRK of July 16, 2009 On Amending the Constitution of the Republic of Karelia. ).

External links

- (in English, Russian, and Finnish) Official website of the Republic of Karelia

- (in English, Russian, and Finnish) Karelia.ru web server

- (in English, Russian, and Finnish) Heninen.net – various information about Karelia

- Information about Karelians

- Tracing Finland's eastern border-thisisFINLAND

- Saimaa Canal links two Karelias-thisisFINLAND

- ProKarelia (also available in other languages)