Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

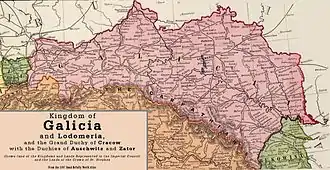

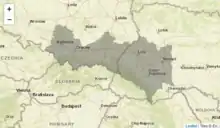

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,[lower-alpha 1] also known as Austrian Galicia or colloquially Austrian Poland, was a constituent possession of the Habsburg monarchy in the historical region of Galicia in Eastern Europe. The crownland was established in 1772. The lands were annexed from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as part of the First Partition of Poland. In 1804 it became a crownland of the newly proclaimed Austrian Empire. From 1867 it was a crownland within the Cisleithanian or Austrian half of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. It maintained a degree of provincial autonomy. Its status remained unchanged until the dissolution of the monarchy in 1918.[3][4]

Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, with the Grand Duchy of Kraków and the Duchies of Auschwitz and Zator Name in different languages ↓ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1772–1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Flag (1890–1918)

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp)  Galicia and Lodomeria (red) within Austria-Hungary in 1914 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Crown land of the Habsburg monarchy (1772–1804) Crownland of the Austrian Empire (1804–1867) Crownland of the Cisleithanian part of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary (1867–1918) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Lemberg | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Official language: German Language of government (since 1867): Polish Minority language: Ruthenian Yiddish By census 1910: Polish 58.6% Ruthenian 40.2%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

Minority

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy (1772–1860) Parliamentary Constitutional Monarchy (1860-1918) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1772–1780 (first) | Maria Theresa | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1916–1918 (last) | Charles I | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1772–1774 (first) | J. A. von Pergen | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1917–1918 (last) | Karl Georg Huyn | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Diet | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| August 5 1772 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| October 19, 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| November 14, 1918 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| September 10, 1919 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• Total | 78,497 km2 (30,308 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1910 | 8,025,675 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Poland Ukraine | ||||||||||||||||||||||

The domain was initially carved in 1772 from the south-western part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. During the following period, several territorial changes occurred. In 1795 the Habsburg monarchy participated in the Third Partition of Poland and annexed additional Polish-held territory, that was renamed as West Galicia. That region was lost in 1809. Some other changes also occurred, by territorial expansion or contraction (1786, 1803, 1809, 1815, 1846, 1849). After 1849, borders of the crownland remained stable until 1918.[5][6]

The name "Galicia" is a Latinized form of Halych, one of several regional principalities of the medieval Kievan Rus'. The name "Lodomeria" is also a Latinized form of the original Slavic name of Volodymyr, that was founded in the 10th century by Vladimir the Great. The title "King of Galicia and Lodomeria" was a late medieval royal title created by Andrew II of Hungary during his conquest of the region in the 13th century. Since that time, the title "King of Galicia and Lodomeria" was included among many ceremonial titles used by the kings of Hungary, thus creating the basis for later (1772) Habsburg claims.[7] In the aftermath of the Galicia–Volhynia Wars, the region was annexed by the Kingdom of Poland in the 14th century and remained in Poland until the 18th-century partitions.

As a result of border changes following World War II, the region of Galicia became divided between Poland and Ukraine. The nucleus of historic Galicia consists of the modern Lviv, Ternopil, and Ivano-Frankivsk regions of western Ukraine.

Ceremonial name

The name of the Kingdom in its ceremonial form, in English: Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria and the Grand Duchy of Kraków with the Duchies of Auschwitz and Zator, existed in all languages spoken there including German: Königreich Galizien und Lodomerien mit dem Großherzogtum Krakau und den Herzogtümern Auschwitz und Zator; Polish: Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii wraz z Wielkim Księstwem Krakowskim i Księstwem Oświęcimia i Zatoru; Ukrainian: Королівство Галичини та Володимирії з великим князіством Краківським і князівствами Освенцима і Затору, romanized: Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii z velykym kniazivstvom Krakivskym i kniazivstvamy Osventsyma i Zatoru, and Hungarian: Galícia és Lodoméria királysága Krakkó nagyhercegségével és Auschwitz és Zator hercegséggel.

History

In 1772, Galicia was the largest part of the area annexed by the Habsburg monarchy in the First Partition of Poland. As such, the later Austrian region of Second Polish Republic which is today part of Ukraine was known as the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria to underline the Hungarian claims to the country. However, after the Third Partition of Poland, a large portion of the ethnically Polish lands to the west (New or West Galicia) was also added to the province, which changed the geographical reference of the term Galicia. Lviv (Lemberg in German) served as the capital of Austrian Galicia, which was dominated by the Polish aristocracy, despite the fact that the population of the eastern half of the province was mostly Ukrainians. In addition to the Polish aristocracy and gentry who inhabited almost all parts of Galicia, and the Ukrainians in the east, there existed a large Jewish population, also more heavily concentrated in the eastern parts of the province.

During the first decades of Austrian rule, Galicia was firmly governed from Vienna, and many significant reforms were carried out by a bureaucracy staffed largely by Germans and Czechs. The aristocracy was guaranteed its rights, but these rights were considerably circumscribed. The former serfs were no longer mere chattels, but became subjects of law and were granted certain personal freedoms, such as the right to marry without the lord's permission. Their labour obligations were defined and limited, and they could bypass the lords and appeal to the imperial courts for justice. The eastern-rite Uniate Church, which primarily served the Ruthenians, was renamed the Greek Catholic Church to bring it on a par with the Roman Catholic Church; it was given seminaries, and eventually, a Metropolitan. Although unpopular with the aristocracy, among the common folk, Polish and Ukrainian/Ruthenian alike, these reforms created a reservoir of good will toward the emperor which lasted almost to the end of Austrian rule. At the same time, however, the Austrian Empire extracted from Galicia considerable wealth and conscripted large numbers of the peasant population into its armed services.

|

Chronology of political history (1815–1914)

|

From 1815 to 1860

In 1815, as a result of decisions of the Congress of Vienna, the Lublin area and surrounding regions (most of the New or West Galicia) were ceded by the Austrian Empire to Congress Poland (Kingdom of Poland), which was ruled by the Tsar, and the Ternopil Region, including the historical region of Southern Podolia, was returned to the Austrian Empire by Russia, which had held it since 1809. The large city of Kraków and surrounding territory, formerly also part of New or West Galicia, became the semi-autonomous Free City of Kraków under supervision of the three powers sharing rule over Poland (i. e., Austria, Russia, and Prussia).

The 1820s and 1830s were a period of bureaucratic rule overseen from Vienna. Most administrative positions were filled by German-speakers, including German-speaking Czechs. After the failure of the November insurrection in Russian Poland in 1830–31, in which a few thousand Galician volunteers participated, many Polish refugees arrived in Galicia. The latter 1830s were rife with Polish conspiratorial organizations whose work culminated in the unsuccessful Galician insurrection of 1846, which was easily put down by the Austrians with the help of a Galician peasantry that remained loyal to the emperor. The insurrection occurred in the western, Polish-populated part of Galicia. Polish manorial gentry supported or were sympathetic to barely concealed plans for an uprising to establish an independent Polish state, but peasants on the manorial estates of western Galicia, reduced to misery by poor harvests, saw little advantage for themselves in a free Poland and seized the opportunity to rise against the institution of serfdom, killing many of the estate owners. With the collapse of the uprising for a free Poland, the city of Kraków lost its semi-autonomy and was integrated into the Austrian Empire under the title of a Grand Duchy, and for practical purposes was made part of Galicia by the Austrian authorities.[9]

In the same period, a sense of national awakening began to develop among the Ruthenians in the eastern part of Galicia. A circle of activists, primarily Greek Catholic seminarians, affected by the romantic movement in Europe and the example of fellow Slavs elsewhere, especially in eastern Ukraine under the Russians, began to turn their attention to the common folk and their language. In 1837, the so-called Ruthenian Triad led by Markiian Shashkevych, published Rusalka Dnistrovaia (The Nymph of the Dniester), a collection of folksongs and other materials in vernacular Ukrainian (then called rusynska, Ruthenian). Alarmed by such democratism, the Austrian authorities and the Greek Catholic Metropolitan banned the book.

In 1848, revolutionary actions broke out in Vienna and other parts of the Austrian Empire. In Lviv, a Polish National Council, and then later, a Ukrainian, or Ruthenian Supreme Council were formed. Even before Vienna had acted, the remnants of serfdom were abolished by the Governor, Franz Stadion, in an attempt to thwart the revolutionaries. Moreover, Polish demands for Galician autonomy were countered by Ruthenian demands for national equality and for a partition of the province into an Eastern, Ruthenian part, and a Western, Polish part. Eventually, Lviv was bombarded by imperial troops and the revolution put down completely.

A decade of renewed absolutism followed, but to placate the Poles, Count Agenor Goluchowski, a conservative representative of the eastern Galician aristocracy, the so-called Podolians, was appointed Viceroy. He began to Polonize the local administration and managed to have Ruthenian ideas of partitioning the province shelved. He was unsuccessful, however, in forcing the Greek Catholic Church to shift to the use of the western or Gregorian calendar, or among Ruthenians generally, to replace the Cyrillic alphabet with the Latin alphabet.

Constitutional experiments

In 1859, following Austro-Hungarian military defeat in Italy, the Empire entered a period of constitutional experiments. In 1860, the Vienna Government, influenced by Agenor Goluchowski, issued its October Diploma, which envisioned a conservative federalization of the empire, but a negative reaction in the German-speaking lands led to changes in government and the issuing of the February Patent which watered down this de-centralization. Nevertheless, by 1861, Galicia was granted a legislative assembly, the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria (Sejm in Polish). Although at first pro-Habsburg Ukrainian and Polish peasant representation was considerable in this body (about half the assembly), and the pressing social and Ukrainian questions were discussed, administrative pressures limited the effectiveness of both peasant and Ukrainian representatives and the diet became dominated by the Polish aristocracy and gentry, who favoured further autonomy. This same year, disturbances broke out in Russian Poland and to some extent spilled over into Galicia. The diet ceased to sit.

By 1863, an open revolt broke out in Russian Poland and from 1864 to 1865 the Austro-Hungarian government declared a state of siege in Galicia, temporarily suspending civil liberties.

The year 1865 brought a return to federal ideas along the lines suggested by Goluchowski and negotiations on autonomy between the Polish aristocracy and Vienna began once again.

Meanwhile, the Ruthenians felt more and more abandoned by Vienna and among the Old Ruthenians grouped around the Greek Catholic Cathedral of Saint George, there occurred a turn towards Russia. The more extreme supporters of this orientation came to be known as Russophiles. At the same time, influenced by the Ukrainian language poetry of the central Ukrainian writer, Taras Shevchenko, an opposing Ukrainophile movement arose which published literature in the Ukrainian/Ruthenian language and eventually established a network of reading halls. Supporters of this orientation came to be known as Populists , and later, as Ukrainians. Almost all Ruthenians, however, still hoped for national equality and for an administrative division of Galicia along ethnic lines.

Galician autonomy

In 1866, following the Battle of Sadova and the Austrian defeat in the Austro-Prussian War, the Austro-Hungarian empire began to experience increased internal problems. In an effort to shore up support for the monarchy, Emperor Franz Joseph began negotiations for a compromise with the Magyar nobility to ensure their support. Some members of the government, such as the Austro-Hungarian prime minister Count Belcredi, advised the Emperor to make a more comprehensive constitutional deal with all of the nationalities that would have created a federal structure. Belcredi worried that an accommodation with the Magyar interests would alienate the other nationalities. However, Franz Joseph was unable to ignore the power of the Magyar nobility, and they would not accept anything less than dualism between themselves and the traditional Austrian élites.

Finally, after the so-called Ausgleich of February 1867, the Austrian Empire was reformed into a dualist Austria-Hungary. Although the Polish and Czech plans for their parts of the monarchy to be included in the federal structure failed, a slow yet steady process of liberalisation of Austrian rule in Galicia started. Representatives of the Polish aristocracy and intelligentsia addressed the Emperor asking for greater autonomy for Galicia. Their demands were not accepted outright, but over the course of the next several years a number of significant concessions were made toward the establishment of Galician autonomy.

From 1873, Galicia was de facto an autonomous province of Austria-Hungary with Polish and, to a lesser degree, Ukrainian or Ruthenian, as official languages. The Germanisation had been halted and the censorship lifted as well. Galicia was subject to the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy, but the Galician Sejm and provincial administration had extensive privileges and prerogatives, especially in education, culture, and local affairs.

These changes were supported by many Polish intellectuals. In 1869 a group of young conservative publicists in Kraków, including Józef Szujski, Stanisław Tarnowski, Stanisław Koźmian and Ludwik Wodzicki, published a series of satirical pamphlets entitled Teka Stańczyka (Stańczyk's Portfolio). Only five years after the tragic end of the January Uprising, the pamphlets ridiculed the idea of armed national uprisings and suggested compromise with Poland's enemies, especially the Austrian Empire, concentration on economic growth, and acceptance of the political concessions offered by Vienna. This political grouping came to be known as the Stanczyks or Kraków Conservatives. Together with the eastern Galician conservative Polish landowners and aristocracy called the "Podolians", they gained a political ascendency in Galicia which lasted to 1914. This shift in power from Vienna to the Polish landowning class was not welcomed by the Ruthenians, who became more sharply divided between Ukrainophiles, who looked to Kyiv and the common people for historic connection, and Russophiles who stressed their connections to Russia.[10]

Both Vienna and the Poles saw treason among the Russophiles and a series of political trials eventually discredited them. Meanwhile, by 1890, an agreement was worked out between the Poles and the "Populist" Ruthenians or Ukrainians which saw the partial Ukrainianization of the school system in eastern Galicia and other concessions to Ukrainian culture. Possibly as a result of this agreement, Ukrainian language students rose sharply in number.[11] Thereafter, the Ukrainian national movement spread rapidly among the Ruthenian peasantry and, despite repeated setbacks, by the early years of the twentieth century this movement had almost completely replaced other Ruthenian groups as the main rival for power with the Poles. Throughout this period, the Ukrainians never gave up the traditional Ruthenian demands for national equality and for partition of the province into a western, Polish half, and an eastern, Ukrainian half. Starting with the election of September 1895, Galicia became known for its "bloody elections" as the Austrian prime minister Count Kasimir Felix Badeni proceeded to rig the election results while having policemen beat those voters were not voting for the government at the poll stations.[12]

| Part of a series on |

| Polish statehood |

|---|

|

| Poland |

|

| Poland portal |

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

The Great Economic Emigration

Beginning in the 1880s, a mass emigration of the Galician peasantry occurred. The emigration started as a seasonal one to Germany (newly unified and economically dynamic) and then later became a Trans-Atlantic one with large-scale emigration to the United States, Brazil, and Canada.

Caused by the backward economic condition of Galicia where rural poverty was widespread, the emigration began in the western, Polish populated part of Galicia and quickly shifted east to the Ukrainian inhabited parts. Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, and Germans all participated in this mass movement of countryfolk and villagers. Poles migrated principally to New England and the midwestern states of the United States, but also to Brazil and elsewhere; Ruthenians/Ukrainians migrated to Brazil, Canada, and the United States, with a very intense emigration from Western Podolia around Ternopil to Western Canada; and Jews emigrated both directly to the New World and also indirectly via other parts of Austria-Hungary. The vast majority of the Ukrainians and Poles who went to Canada prior to 1914 came from either Galicia or the neighboring Bukovina province of the Austrian empire.[13] In 1847, 1849, 1855, 1865, 1876 and 1889, there were famines in Galicia that led to thousands starving to death, which increased the sense that life in Galicia was hopeless and inspired people to leave in search of a better life in the New World.[13] Adding to the exodus were the inheritance laws in Galicia adopted in 1868 which stated that the land should be equally divided amongst the sons of a peasant, which owning to the tendency of Galician peasants to have large families led to the land being divided into so many small holdings as to make farming uneconomical.[14]

A total of several hundred thousand people were involved in this Great Economic Emigration which grew steadily more intense until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The war put a temporary halt to emigration which never again reached the same proportions. The Great Economic Emigration, especially the emigration to Brazil, the "Brazilian Fever" as it was called at the time, was described in contemporary literary works by the Polish poet Maria Konopnicka, the Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko, and many others. Some states in south of Brazil have a large percentage of their population formed by direct descendants of these Ruthenian/Ukrainian immigrants.

When it comes to social relations, most especially between peasants and landlords, the area was the most undeveloped in the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Galician peasantry was always living at the verge of starvation. This led the Polish peasants to call the area "Krolestwo Goloty i Glodomerji" i.e. "The Kingdom of Bareness and Starvation". Tsar Alexander II had officially banned serfdom and liberated the serfs in the Russian Empire in the 1870s and enacted legislation to protect the serfs. But in Galicia the serfs could be coerced or forced through predatory practices back into serfdom by the affluent Polish merchant class and local nobility a condition which lasted until the start of World War I.

At the time of these emigrations in the 1890s many Polish and Ukrainian liberals saw Galicia as a Galician Piedmont as a Polish Piedmont and a Ukrainian Piedmont. Because Italians had started their liberation from Austrian rule in the Italian Piedmont these Ukrainian and Polish nationalists felt that the liberation of their two countries would begin in Galicia.

In spite of almost 750,000 persons emigrating across the Atlantic from 1880 to 1914 Galicia's population increased by 45% between 1869 and 1910.[15]

First World War and Polish-Ukrainian conflict

During the First World War Galicia saw heavy fighting between the forces of Russia and the Central Powers. The Imperial Russian Army overran most of the region in 1914 after defeating the Austro-Hungarian Army in a chaotic frontier battle in the opening months of the war. They were in turn pushed out in the spring and summer of 1915 by a combined German and Austro-Hungarian offensive.

In late 1918 Eastern Galicia became a part of the restored Republic of Poland, which absorbed the Lemko-Rusyn Republic. The local Ukrainian population briefly declared the independence of Eastern Galicia as the West Ukrainian People's Republic. During the Polish-Soviet War the Soviets tried to establish the puppet-state of the Galician SSR in East Galicia, the government of which after couple of months was liquidated.

The fate of Galicia was settled by the Peace of Riga on March 18, 1921, giving all of Galicia to the Second Polish Republic. Although never accepted as legitimate by some Ukrainians, it was internationally recognized with significant French support on May 15, 1923.[16] The French support for Polish rule of ethnically Ukrainian eastern Galicia and its oil resources in the Borysław-Drohobycz basin were rewarded by Warsaw allowing significant French investment to pour into the Galician oil industry.[15] The Poles had convinced the French that since less than 25% of the ethnic Ukrainians were literate before the Great War and Ukrainians were novices in governing themselves, only the Poles, not the Ukrainians, would be able to administer eastern Galicia and its precious oil assets.[15]

The Ukrainians of the former eastern Galicia and the neighbouring province of Volhynia made up about 12% of the population of the Second Polish Republic, and were its largest minority. As Polish government policies were unfriendly towards minorities, tensions between the Polish government and the Ukrainian population grew, eventually giving the rise to the militant underground Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists.

Administrative divisions

Soon after the first partition of Poland the newly acquired Polish territories (see First Partition of Poland) which were known as Kreise (Voivodeship in Poland) were restructured in November 1773 into 59 Kreisdistriktes (Land districts), while the Kreise were abolished. Some former voivodeships were incorporated completely, while most of them only partially. Among them were the former voivodeships of Belz, Red Ruthenia, Cracow, Lublin, Sandomierz, and Podolie. Also during the Russo-Turkish War in 1769, the northwestern territory of Moldavia (renamed Bukovina) was occupied by the Russian Empire which ceded it in 1774 to the Austrian Empire as a "token of appreciation".

Administrative division

The Kingdom was split into numerous counties (powiats) which in 1914 were about 75.[17] Besides Lviv (Lwów in Polish) being the capital of the Kingdom, Kraków was considered as the unofficial capital of the western part of Galicia and the second most important city in the region.

- Belz (Polish: Bełz, Yiddish: Beltz)

- Berezhany (Polish: Brzeżany)

- Biecz (German: Beitsch, Ukrainian: Беч, Bech)

- Bochnia (German: Salzberg)

- Boryslav (Polish: Borysław)

- Brody (Yiddish: Brod)

- Busk

- Buchach (Polish: Buczacz)

- Chortkiv (Polish: Czortkow)

- Chrzanów

- Dukla (Ukrainian: Дукля, Duklia)

- Drohobych (Polish: Drohobycz)

- Gorlice (Ukrainian: Горлиці, Horlytsi, German: Gorlitz)

- Halych (Polish: Halicz, German: Halitsch, Yiddish: Galits)

- Husiatyn

- Jarosław (German: Jaroslau, Ukrainian: Ярослав, Yaroslav)

- Jasło (German: Jassel)

- Kalush (Polish: Kałusz)

- Kolomyia (German: Kolomea, Polish: Kołomyja, Romanian: Colomeea, Yiddish: Kolomay)

- Kozova (Polish: Kozowa)

- Kraków (German: Krakau, Yiddish: Kruke)

- Krosno (German: Krossen, Ukrainian: Коросно, Korosno)

- Lesko (Ukrainian: Лісько, Lisko, Yiddish: Linsk)

- Leżajsk (German: Lyschansk, Yiddish: Lizhensk)

- Limanowa (German: Ilmenau)

- Lviv (German: Lemberg, Polish: Lwów, Yiddish: Lemberik)

- Łańcut (German: Landshut)

- Machliniec (Ukrainian: Махлинець, Makhlynets)

- Myślenice (German: Mischlenitz)

- Nadvirna (Polish: Nadwórna)

- Nowy Sącz (German: Neu Sandez, Yiddish: Zanz)

- Oświęcim (German: Auschwitz, Yiddish: Oshpetsin)

- Peremyshliany (Polish: Przemyślany)

- Przemyśl (Ukrainian: Перемишль, Peremyshl)

- Pidhaytsi (Polish: Podhajce)

- Rava-Ruska (Polish: Rawa Ruska, Yiddish: Rave)

- Rohatyn (Ukrainian: Рогатин, Yiddish: ראהאטין)

- Rymanów (German: Reimannshau)

- Rzeszów (Yiddish: Rejsza, Ukrainian: Riashiv, German: Reichshof)

- Sambir (Polish: Sambor)

- Sanok (Ukrainian: Сянік, Sianik, Yiddish: Sonik, Hungarian: Sánók)

- Stanyslaviv (Polish: Stanisławów, German: Stanislau, Yiddish: Stanislev; renamed in 1962 to Ivano-Frankivsk)

- Terebovlia (Polish: Trembowla)

- Ternopil' (Polish: Tarnopol)

- Tarnów (Ukrainian: Тарнів, Tarniv, German: Tarnau)

- Tomaszów Lubelski (Ukrainian: Tomashiv Liublinskyi)

- Truskavets (Polish: Truskawiec)

- Wieliczka (German: Groß Salze)

- Zalishchyky (Polish: Zaleszczyki)

- Zator (German: Neuenstadt an der Schaue)

- Zolochiv (Polish: Złoczów, Yiddish: Zlotshev)

- Zhovkva (Polish: Żółkiew)

- Żywiec (Ukrainian: Живець, Zhyvets, German: Saybusch)

West Galicia

West Galicia was part of the Kingdom from 1795 to 1809, until 1803 as a separate administrative unit.

Bukovina District

Bukovina was part of the Kingdom from 1775 to 1849 (after 1849: Duchy of Bukovina).

Free City of Kraków

Kraków was a condominium with Prussia and Russia from 1815 to 1846, part of the Kingdom from 1846.

Government

After the partition of Poland the region was government by an appointed governor, later a vice-regent. During the war time the office of vice-regent was supplemented by a military-governor. In 1861 a regional assembly was established, the Sejm of the Land, which initially due to lack of adequate administrative building was located in the building of the Skarbek Theatre until 1890.

Vice-Regents

List of vice-regents since 1900:

- Count Leon Piniński (March 31, 1898 – June 1903)

- Count Andrzej Potocki (June 8, 1903 – April 12, 1908)

- Count Michał Bobrzyński (April 28, 1908 – May 14, 1913)

- Witold Korytowski (May 14, 1913 – August 20, 1915)

- Russian occupation (September 1914 – 1915)

- Hermann von Colard (August 1915 – April 8, 1916)

- Baron Erich von Diller (April 1916 – March 1917), exiled due to Russian occupation

- Russian occupation (1916 – July 26, 1917)

- Count Karl Georg Huyn (1917 – November 1, 1918), in fact subordinate to the Regency Council and its General Commissar Prince Witold Leon Czartoryski instead of the Austrian Crown.

Political

- Chief Ruthenian Council (May 2, 1848 – 1851), headed by Gregory Yakhimovich and later by Mykhailo Kuzemsky. It consisted of 30 members.

- Ruthenian Council (Lviv) (1870–1814)

- Ruthenian Congress (May 23, 1848) was an oppositional political formation to the Chief Ruthenian Council to which belong such personalities as Ivan Vahylevych, Julian Lawriwskyj, Leon Sapieha, and others.

- Ukrainian National Democratic Party (1899–1919) was created in place of the People's Council (1885–1899), eventually becoming part of the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance (UNDO)

- Ukrainian Radical Party (1890–1939)

- Christian-Social Party (1896–1930), until 1911 was called as Catholic-Ruthenian People's Union, in 1930 it split when some members joined UNDO, while others created Ukrainian Catholic People's Party.

- Ukrainian Social Democratic Party (1899–1939), was created by some members of the Ukrainian Radical Party and in 1924 partially merged with Communist Party of Western Ukraine (1919–1938)

- Ukrainian General Council (1914–1916), initially as the Chief Ukrainian Council, was a national political bloc of most of the Ukrainian parties. It laid foundation for creating the Ukrainian state in the West Ukraine.

Public

- Ukrainian Forum (Besida) (until 1928 Ruthenian Forum) (1861–1939), a forum-type association created by Julian Lawriwskyj based on the Lviv intelligentsia circle, "Young Rus". The organization established its own Ukrainian-based professional theater (1864–1924).

- Prosvita (1868–present)

- Shevchenko Scientific Society (1873–present)

- Ruthenian Triad (1833–1843), literary organization discontinued after the death of Markiyan Shashkevych

- Academic Society (Hromada) (1882–1921), until 1896 as Brotherhood

- Academical Circle (1874–1877)

- Sokół and Sokil sport organization created in light of the European Sokol movement

- Sich and Plast

- Luh, a fireman society

- Riflemen's Association

Demographics

In 1773, Galicia had about 2.6 million inhabitants in 280 cities and markets and approx. 5,500 villages. There were nearly 19,000 noble families with 95,000 members (about 3% of the population). The "non-free" accounted for 1.86 million, more than 70% of the population. A small number were full farmers, but by far the overwhelming number (84%) had only smallholdings or no possessions.

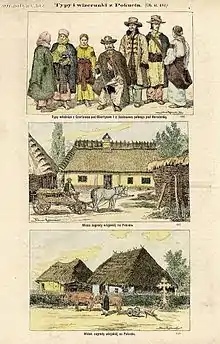

No country of the Austrian monarchy had such a varied ethnic mix as Galicia: Poles, Ruthenians, Germans (Galician Germans), Armenians, Jews, Hungarians, Romani people, Lipowaner, etc. The Poles were mainly in the west, with the Ruthenians (Ukrainians) predominant in the eastern region (Ruthenia).

The Jews of Galicia had immigrated in the Middle Ages from Germany and mostly spoke Yiddish as their first language. German-speaking people were more commonly referred to as "Saxons" or "Swabians", even though most of them did not come from Saxony or Swabia (cf. Transylvanian Saxons and Danube Swabians). There were also some Mennonites who mostly came originally from Switzerland, but spoke a dialect of Palatine German which is close to Pennsylvania German. With inhabitants who had a clear difference in language such as with the Saxons or the Roma identification was less problematic, but widespread multilingualness blurred the borders again.

It is however possible to make a clear distinction in religious denominations: the majority of the Poles were Latin Catholics, while the Ruthenians were mostly Greek Catholics. The Jews, who represented the third largest religious group, were mostly traditional in their religious observance which later developed into Orthodox Judaism. The Jewish community had a strong sense of Galician identity and called themselves Galitzianer to distinguish themselves from the other Ashkenazi communities of Eastern Europe.[18] The Jewish community of Galicia was largely Orthodox or Hasidic in 1772 and many regarded the reforms introduced by the Emperor Joseph II such as the introduction of conscription as a form of oppression, leading the Galitzianer to split between the Orthodox and Hasidic communities committed to the traditional values vs. the "modernizers" who wanted to change.[18]

The average life expectancy was 27 years for men and 28.5 years for women, as compared to 33 and 37 in Bohemia, 39 and 41 in France and 40 and 42 in England. Also the quality of life was much lower as Galicia was the poorest province in the Austrian empire.[18] The yearly consumption of meat did not exceed 10 kg (22 lb) per capita, as compared to 24 kg (53 lb) in Hungary and 33 in Germany. This was mostly due to much lower average income. In 2014, The Economist reported: "Poverty in Galicia in the 19th century was so extreme that it had become proverbial—the region was called Golicja and Glodomeria, a play on the official name (Galicja i Lodomeria) and goly (naked) and glodny (hungry)."[18]

In 1888 Galicia extended over 78,550 square kilometres (30,328 sq mi) and had a population of about 6.4 million people, including 4.8 million peasants (75% of the whole population). The population density, at 81 people per square kilometre, was higher than that of France (71 inhabitants/km2) or Germany. The population rose to 7.3 million in 1900 and to 8 million in 1910.[19]

| Religion | Adherents | |

|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | 3,731,569 | 46.5% |

| Greek Catholic (Uniates) | 3,379,613 | 42.1% |

| Jewish | 871,895 | 10.9% |

| Protestant | 37,144 | 0.5% |

| Other | 5,454 | <0.1% |

| Total | 8,025,675 | |

Economy

Galicia was economically the least developed part of Austria and received considerable transfer payments from the Vienna government. Its level of development was comparable to or higher than that of Russia and the Balkans, but well behind Western Europe.

The first detailed description of the economic situation of the region was prepared by Stanislaw Szczepanowski (1846–1900), a Polish lawyer, economist and chemist who in 1873 published the first version of his report titled Nędza galicyjska w cyfrach (The Galician Poverty in Numbers). Based on his own experience as a worker in the India Office, as well as his work on development of the oil industry in the region of Boryslav and the official census data published by the Austro-Hungarian government, he described Galicia as one of the poorest regions in Europe.

Statistics indicate the Galicia and Lodomeria was poorer than areas west of it. The average income per capita did not exceed 53 Rhine guilders (RG), as compared to 91 RG in the Kingdom of Poland, 100 in Hungary and more than 450 RG in England at that time. Also the taxes were relatively high and equalled to 9 Rhine guilders a year (c. 17% of yearly income), as compared to 5% in Prussia and 10% in England. Also the percentage of people with higher income was much lower than in other parts of the Monarchy and Europe: the luxury tax, paid by people whose yearly income exceeded 600 RG, was paid by 8 people in every 1,000 inhabitants, as compared to 28 in Bohemia and 99 in Lower Austria. Despite high taxation, the national debt of the Galician government exceeded 300 million RG at all times, that is approximately 60 RG per capita.

All in all, the region was used by the Austro-Hungarian government mostly as a reservoir of cheap workforce and recruits for the army, as well as a buffer zone against Russia. It was not until early in the 20th century that heavy industry started to be developed, which would be comparable to much of Russia and the Balkans. Even then it was mostly connected to war production. The biggest state investments in the region were the railways and the fortresses in Przemyśl, Kraków and other cities. Industrial development was mostly connected to the private oil industry started by Robert Doms and to the Wieliczka salt mines, operational since at least the Middle Ages.

Industry

In 1880, industry in Galicia was at a low level. In 1857 Galicia had 102,189 persons or 2.2% of the population worked in industry. By 1870 that number had risen to 179,626, or 3.3% of the population.

Oil and natural gas industry

Near Drohobych and Boryslav in Galicia, significant oil reserves were discovered and developed during the mid 19th and early 20th centuries.[20][21] The first European attempt to drill for oil was in Bóbrka in western Galicia in 1854.[20][21] By 1867, a well at Kleczany, in Western Galicia, was drilled using steam to about 200 meters.[20][21] On December 31, 1872, a railway line linking Borysław (now Boryslav) with the nearby city of Drohobycz (now Drohobych) was opened. American John Simon Bergheim and Canadian William Henry McGarvey came to Galicia in 1882.[22][lower-alpha 2] In 1883, their company, MacGarvey and Bergheim, bored holes of 700 to 1,000 meters and found large oil deposits.[20] In 1885, they renamed their oil developing enterprise the Galician-Karpathian Petroleum Company (German: Galizisch-Karpathische Petroleum Aktien-Gesellschaft), headquartered in Vienna, with McGarvey as the chief administrator and Bergheim as field engineer,[lower-alpha 3] and built a huge refinery at Maryampole near Gorlice, in the southeast corner of Galicia.[22] Considered the biggest, most efficient enterprise in Austro-Hungary, Maryampole was built in six months and employed 1000 men.[22][lower-alpha 4] Subsequently, investors from Britain, Belgium, and Germany established companies to develop the oil and natural gas industries in Galicia.[20] This influx of capital caused the number of petroleum enterprises to shrink from 900 to 484 by 1884, and to 285 companies manned by 3,700 workers by 1890.[20] However, the number of oil refineries increased from thirty-one in 1880 to fifty-four in 1904.[20] By 1904, there were thirty boreholes in Borysław of over 1,000 meters.[20] Production increased by 50% between 1905 and 1906 and then trebled between 1906 and 1909 because of unexpected discoveries of vast oil reserves of which many were gushers.[15] By 1909, production reached its peak at 2,076,000 tons or 4% of worldwide production.[20][21] Often called the "Polish Baku", the oil fields of Borysław and nearby Tustanowice accounted for over 90% of the national oil output of the Austria-Hungary Empire.[15][20][23] From 500 residents in the 1860s, Borysław had swollen to 12,000 by 1898.[15] In 1909, Polmin with headquarters in Lviv was established for the extraction and distribution of natural gas. At the turn of the century, Galicia was ranked fourth in the world as an oil producer.[20][lower-alpha 5] This significant increase in oil production also caused a slump in oil prices.[15] A very rapid decrease in oil production in Galicia occurred just before the Balkans conflicts.

Galicia was the Central Powers' only major domestic source of oil during the Great War.[15]

Culture

Flag

Until 1849, Galicia and Lodomeria was a single province with Bukovina and used the blue-red flag (consisting of two horizontal stripes: the upper one was blue, the lower one was red).

In 1849, Bukovina was given an independent status from that of Galicia-Lodomeria and kept the blue-red flag. Galicia was given a new flag consisting of three horizontal stripes being blue, red and yellow.

That flag remained in use until 1890, when Galicia-Lodomeria received a new flag consisting of two horizontal stripes being red and white. It remained in use until the dissolution of the Kingdom of Galicia-Lodomeria in 1918 and is displayed in Ströhl's Oesterreichisch-ungarische Wappenrolle (1898).

.svg.png.webp) 1772–1800, 1849–90

1772–1800, 1849–90.svg.png.webp) 1800–49, 1890-1918

1800–49, 1890-1918

- References

- Jan Miller: Chorągwie i flagi polskie, Instytut Wydawniczy "Nasza Księgarnia", Warsaw 1962,

- Hugo Ströhl: Oesterreichisch-ungarische Wappenrolle, Vienna 1898

Military

The Kingdom was divided into three major military districts centered in Kraków, Lviv, and Przemyśl. Local military used a specialized language for communication known as Army Slav. One of the major army units was the 1st Army consisting of 1st (Kraków), 5th (Pressburg), and 10th (Przemyśl) Corps.

Selected units (1914); command language German

Eight out of 11 Lancer regiments were located in Galicia (see Uhlan)

- 1st Galicia Lancer Regiment of Ritter von Brudermann (85% Poles) (Regimental language Polish)

- 2nd Galicia Lancer Regiment of Fürst zu Schwarzenberg (84% Poles) (Regimental language Polish)

- 3rd Galicia Lancer Regiment of Archduke Carl (69% Poles, 26% Ukrainians) (Regimental language Polish)

- 4th Galicia Lancer Regiment "Kaiser" (65% Ukrainians, 29% Poles) (Regimental language Polish and Ukrainian)

- 6th Galicia Lancer Regiment of Kaiser Joseph II (52% Poles, 40% Ukrainians) (Regimental language Polish and Ukrainian)

- 7th Galicia Lancer Regiment of Archduke Franz Fedinand (72% Ukrainians, 22% Poles) (Regimental language Ukrainian)

- 8th Galicia Lancer Regiment of Count Auersperg (80% Poles) (Regimental language Polish)

- 13th Galicia Lancer Regiment of Eduard von Böhm-Ermolli (55% Ukrainians, 42% Poles) (Regimental language Polish and Ukrainian)

- 1st Army Lancer Regiment (65% Ukrainians, 30% Poles)

- 3rd Army Lancer Regiment (69% Poles, 26% Ukrainians)

- 4th Army Lancer Regiment (85% Poles)

One Dragoon regiment

- 9th Galicia-Bukowina Dragoon Regiment of Archduke Albrecht (50% Romanians, 29% Ukrainians) (Regimental language Romanian and Ukrainian)

10 Infantry regiments

- 16th Army Infantry Regiment "Krakau" (82% Poles)

- 17th Army Infantry Regiment "Rzeszów" (97% Poles)

- 18th Army Infantry Regiment "Przemyśl" (47% Ukrainians, 43% Poles)

- 19th Army Infantry Regiment "Lemberg" (59% Ukrainians, 31% Poles)

- 20th Army Infantry Regiment "Stanislau" (72% Ukrainians)

- 32nd Army Infantry Regiment (91% Poles), Tarnów

- 33rd Army Infantry Regiment (73% Ukrainians), Stryi

- 34th Army Infantry Regiment (75% Poles), Jarosław

- 35th Army Infantry Regiment (68% Ukrainians, 25% Poles), Zolochiv

- 36th Army Infantry Regiment (70% Ukrainians, 21% Poles), Kolomea

Two Artillery divisions

- 43rd Field Artillery Division (55% Ukrainians, 25% Poles), Lemberg

- 45th Field Artillery Division (60% Ukrainians, 25% Poles), Przemyśl

Five Feldjäger battalions (Military Police)

- 4th Galicia Feldjäger Battalion (77% Poles), Braunau am Inn (Rzeszow district)

- 12th Bohemia Feldjäger Battalion (67% Czech, 32% German), Cavalese (Kraków district)

- 14th Feldjäger Battalion (47% Ukrainians, 43% Poles), Mezzolombardo (Przemyśl district)

- 18th Feldjäger Battalion (59% Ukrainians, 31% Poles), Trient (Lviv district)

- 30th Galicia-Bukowina Feldjäger Battalion (70% Ukrainians), Steyr (Stanislav district)

Others

- 10th Engineer Battalion (50% Poles, 30% Ukrainians) (Przemyśl)

- 1st Sapper Battalion (50% Poles, 23% Germans, 23% Czechs) (Krakau)

- 10th Sapper Battalion (50% Poles, 30% Ukrainians) (Przemyśl)

- 11th Sapper Battalion (48% Ukrainians, 32% Poles) (Lemberg)

- Polish Legions

- Ukrainian Legions, later as part of the battle group of Archduke Wilhelm

- 1st Ukrainian Cossack Rifle Division (1918)

The memory of Galicia

In 2014, the Polish historian Jacek Purchla stated that there were two ways of remembering Galicia, namely as an idyllically innocent multi-cultural land, of a simpler and better time compared to the present vs. the Austrian view of Galicia as a Halb-Asien ("half-Asia") as Austrian officials always regarded Galicia as "a barbaric place inhabited by strange people of questionable personal hygiene".[18] Galicia was always considered in Vienna to be a colony in need of being "civilized", and as a result, the Austrians never considered Galicia to be a part of Austria proper.[18] Both the Polish and Ukrainian communities of Galicia saw the province as their "Piedmont" where plans for an independent Polish or Ukrainian state were broached, making the memory of Galicia under Austrian rule a central part of Polish and Ukrainian national memories.[18] In 2014, Purchla stated: "The latest proof of the political significance of the Galician heritage has been the contribution of its Ukrainian parts to the success of the Maidan [revolution] this year and last year".[18] Starting in the late 19th century, about 2 million Galician Jews immigrated to the United States, and amongst the descendants of the Galitzianer in the United States that the memory of Galicia as either a lost paradise or as a backward province to escape from is kept alive.[18] The Economist reported: "In Europe, Galicia is a central element of Poles’ national identity and of Ukrainians’ search for a European identity."[18]

See also

- Bukovina

- Kingdom of Halych-Volhynia

- Galician Soviet Socialist Republic

- Lesser Poland

- Galician slaughter

- List of towns of the former Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

- Gesher Galicia

Notes

- German: Königreich Galizien und Lodomerien, [ˈkøːnɪkˌʁai̯ç ɡaˈliːtsi̯ən ʊnt lodoˈmeːʁi̯ən]; Polish: Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, [kruˈlɛstfɔ ɡaˈlitsji i lɔdɔˈmɛrji]; Ukrainian: Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, romanized: Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; Latin: Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae

- William McGarvey helped develop a rig in the 1860s or 1870s which made his Canadian drilling technology and Canadian drillers famous around the world. John Simon Bergheim and William Henry McGarvey had unsuccessfully searched for oil in Germany under the Continental Oil Company of which McGarvey was the director. They left Germany and began their first drilling in Galicia during 1882 under the company name of MacGarvey and Bergheim.[22]

- Just after the turn of the century, Bergheim was killed in a taxicab accident in London, England, leaving McGarvey to carry on alone.[22]

- Later, Bergheim and McGarvey bought a number of small oil-producing and refining operations and acquired the Apollo Oil Company of Budapest.[22]

- In 1909, first in the world for oil production was the United States with 183,171,000 barrels, the Russian Empire was second with 65,970,000 barrels, and the Austria-Hungary Empire was third with 14,933,000 barrels per year due to its significant oil reserves discoveries between 1905 and 1909.[15][24]

References

- Anstalt G. Freytag & Berndt (1911). Geographischer Atlas zur Vaterlandskunde an der österreichischen Mittelschulen. Vienna: K. u. k. Hof-Kartographische. "Census December 31st 1910"

- Unofficially was called as Rynsky or Zoloty Rynsky. Handbook on history of Ukraine.

- Magocsi 1983, p. 92-115.

- Wolff 2010, p. 1-11.

- Magocsi 1983, p. 116-173.

- Wolff 2008, p. 277-300.

- Wolff 2004, p. 818-840.

- Prothero, G W (1920). Austrian Poland. Peace handbooks. Great Britain. Foreign Office. Historical Section: H.M. Stationery Office, London, via World Digital Library. p. 14. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- Prothero, G W (1920). Austrian Poland. Peace handbooks. Great Britain. Foreign Office. Historical Section: H.M. Stationery Office, London, via World Digital Library. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- Ronald Grigor Suny, Michael D. Kennedy (2001). Intellectuals and the Articulation of the Nation. University of Michigan. p. 138. ISBN 9780472088287.

- Börries Kuzmany (2017). Brody: A Galician Border City in the Long Nineteenth Century. BRILL. p. 210. ISBN 9789004334847.

- Prymak, Thomas M. (2015). Gathering a Heritage: Ukrainian, Slavonic, and Ethnic Canada and the USA. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1442665507.

- Prymak, Thomas M. (2015). Gathering a Heritage: Ukrainian, Slavonic, and Ethnic Canada and the USA. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1442665507.

- Prymak, Thomas M. (2015). Gathering a Heritage: Ukrainian, Slavonic, and Ethnic Canada and the USA. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1442665507.

- Frank, Allison (June 29, 2006). "Galician California, Galician Hell: The Peril and Promise of Oil Production in Austria-Hungary". Washington, D.C.: Office of Science and Technology Austria (OSTA). Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- French: Les Alliés reconnaissent à la Pologne la possession de la Galicie, Chronologie des civilisations, Jean Delorme, Paris, 1956.

- Map of the Kingdom with its county division (Lenius, Brian. "Genealogical Gazetteer of Galicia" 2nd ed. Anola, Canada. 1993) Archived 2012-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "A successful Austrian invention". The Economist. 15 November 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- "Austria-Hungary: historical demographical data of the administrative division prior to 1918". Populstat. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- Schatzker, Valerie; Erdheim, Claudia; Sharontitle, Alexander. "Petroleum in Galicia". Drohobycz Administrative District: History. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- Golonka, Jan; Picha, Frank J. (2006). The Carpathians and Their Foreland: Geology and Hydrocarbon Resources. American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG). ISBN 9780891813651.

- Creswell, Sarah; Flint, Tom. "William H. McGarvey (1843–1914)". Professional Engineers Ontario. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- Thompson, Arthur Beeby (1916). Oil-field Development and Petroleum Mining. Van Nostrand.

- Schwarz, Robert (1930). Petroleum-Vademecum: International Petroleum Tables (VII ed.). Berlin and Vienna: Verlag für Fachliteratur. pp. 4–5.

- Magocsi 1983, p. 106.

- Subtelny, Orest. "Ukraine: a history (Gazette de Leopol)". p. 283. (in English)

- Subtelny, Orest. "Ukraine: a history (Zoria Halytska)". p. 248. (in English)

Sources

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1983). Galicia: A Historical Survey and Bibliographic Guide. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802024824.

- Wolff, Larry (2004). "Inventing Galicia: Messianic Josephinism and the Recasting of Partitioned Poland". Slavic Review. 63 (4): 818–840. doi:10.2307/1520422. JSTOR 1520422. S2CID 155170075.

- Wolff, Larry (2008). "Kennst du das Land? The Uncertainty of Galicia in the Age of Metternich and Fredro". Slavic Review. 67 (2): 277–300. doi:10.1017/S0037677900023536. JSTOR 27652844. S2CID 164814456.

- Wolff, Larry (2010). The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804774291.

Further reading

- Norman Davies Vanished Kingdoms: The History of Half-Forgotten Europe. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-84614-338-0

- Andrei S. Markovits and Frank E. Sysyn, eds., Nationbuilding and the Politics of Nationalism: Essays on Austrian Galicia (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1982). Contains an important article by Piotr Wandycz on the Poles, and an equally important article by Ivan L. Rudnytsky on the Ukrainians.

- Christopher Hann and Paul Robert Magocsi, eds., Galicia: A Multicultured Land (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005). A collection of articles by John Paul Himka, Yaroslav Hrytsak, Stanislaw Stepien, and others.

- Taylor, A. J. P., The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918, 1941, discusses Habsburg policy toward ethnic minorities.

- Alison Fleig Frank, Oil Empire: Visions of Prosperity in Austrian Galicia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005). A new monograph on the history of the Galician oil industry in both the Austrian and European contexts.

- Drdacki, Moritz knight by Ostrow, the glad patents Galziens a contribution to customer of the Unterthanswesens, printed with J.P. Sollinger, Vienna, 1838, Reprint 1990, Scherer publishing house Berlin, ISBN 3-89433-024-4

- Kratter, F., letters over itzigen condition of Galicia a contribution to the Staatistik and knowledge of human nature, publishing house G. Ph. of usurer, Leipzig 1786, Reprint 1990, Scherer publishing house Berlin, ISBN 3-89433-001-5

- Mueller, Sepp, from the settlement to the resettlement, Wiss. contribution to history and regional studies of east Central Europe, hrsg. v. Joh. Gottfr. Herder Joh.-Gottfr.-Herder-Institut Marburg, NR. 54 Rohrer, Josef, remarks on a journey of the Turkish Graenze over the Bukowina by east and west Galicia, Schlesien and Maehren to Vienna, publishing house Anton Pichler, Vienna 1804, Reprint 1989, Scherer publishing house Berlin, ISBN 3-89433-010-4

- statistic Central Commission (Hrsg.), local repertory of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomerien with the Herzogthume Krakau, publishing house Carl Gerolds son, Vienna 1874, Reprint 1989, Scherer publishing house Berlin, ISBN 3-89433-015-5

- Stupnicki, Hipolit, the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomerien sammt the Grossherzogthume Krakau and the Herzogthume Bukowina in geographical-historical-statistic relationship, printed with Peter Piller, Lviv 1853, Reprint 1989, Scherer publishing house Berlin, ISBN 3-89433-016-3

- Traunpaur, Alfons Heinrich Chevalier d'Orphanie, Dreyssig of letters over Galicia or observations of a[n] unpartheyischen man, Vienna 1787, Reprint 1990, Scherer publishing house Berlin, ISBN 3-89433-013-9