Korean language

Korean (South Korean: 한국어, hangugeo; North Korean: 조선말, chosŏnmal) is the native language for about 80 million people, mostly of Korean descent.[lower-alpha 1][1] It is the official and national language of both North Korea and South Korea (geographically Korea), but over the past 74 years of political division, the two Koreas have developed some noticeable vocabulary differences. Beyond Korea, the language is recognised as a minority language in parts of China, namely Jilin Province, and specifically Yanbian Prefecture and Changbai County. It is also spoken by Sakhalin Koreans in parts of Sakhalin, the Russian island just north of Japan, and by the Koryo-saram in parts of Central Asia.[2] The language has a few extinct relatives which—along with the Jeju language (Jejuan) of Jeju Island and Korean itself—form the compact Koreanic language family. Even so, Jejuan and Korean are not mutually intelligible with each other. The linguistic homeland of Korean is suggested to be somewhere in contemporary Northeast China.[2] The hierarchy of the society from which the language originates deeply influences the language, leading to a system of speech levels and honorifics indicative of the formality of any given situation.

| Korean | |

|---|---|

| 한국어 (South Korea) 조선말 (North Korea) | |

| |

| Pronunciation | Korean pronunciation: [ha(ː)n.ɡu.ɡʌ] (South Korea) Korean pronunciation: [tso.sɔn.mal] (North Korea) |

| Native to | Korea |

| Ethnicity | Koreans |

Native speakers | 80.4 million (2020)[1] |

Koreanic

| |

Early forms | Proto-Koreanic

|

Standard forms |

|

| Dialects | Korean dialects |

| Hangul / Chosŏn'gŭl (Korean script) Hanja / Hancha (Historical) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ko |

| ISO 639-2 | kor |

| ISO 639-3 | kor |

Linguist List | kor |

| Glottolog | kore1280 |

| Linguasphere | 45-AAA-a |

Countries with native Korean-speaking populations (established immigrant communities in orange and green). | |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Korea |

|---|

| History |

Modern Korean is written in the Korean script (한글; Hangul in South Korea, 조선글; Chosŏn'gŭl in North Korea), a system developed during the 15th century for that purpose, although it did not become the primary script until the 20th century. The script uses 24 basic letters (jamo) and 27 complex letters formed from the basic ones. When first recorded in historical texts, Korean was only a spoken language; all written records were maintained in Classical Chinese, which, even when spoken, is not intelligible to someone who speaks only Korean. Later, Chinese characters adapted to the Korean language, Hanja (漢字), were used to write the language for most of Korea's history and are still used to a limited extent in South Korea, most prominently in the humanities and the study of historical texts.

Since the turn of the 21st century, aspects of Korean culture have spread to other countries through globalization and cultural exports. As such, interest in Korean language acquisition (as a foreign language) is also generated by longstanding alliances, military involvement, and diplomacy, such as between South Korea–United States, China–North Korea and North Korea–Russia since the end of World War II and the Korean War. Along with other languages such as Chinese and Arabic, Korean is ranked at the top difficulty level for English speakers by the U.S. Department of Defense.

History

Modern Korean descends from Middle Korean, which in turn descends from Old Korean, which descends from the Proto-Koreanic language which is generally suggested to have its linguistic homeland.[3][4] Whitman (2012) suggests that the proto-Koreans, already present in northern Korea, expanded into the southern part of the Korean Peninsula at around 300 BC and coexisted with the descendants of the Japonic Mumun cultivators (or assimilated them). Both had influence on each other and a later founder effect diminished the internal variety of both language families.[5]

Since the Korean War, through 70 years of separation, North–South differences have developed in standard Korean, including variations in pronunciation and vocabulary chosen, but these minor differences can be found in any of the Korean dialects, which are still largely mutually intelligible.

Writing systems

Chinese characters arrived in Korea (see Sino-Xenic pronunciations for further information) together with Buddhism during the Proto-Three Kingdoms era in the 1st century BC. They were adapted for Korean and became known as Hanja, and remained as the main script for writing Korean for over a millennium alongside various phonetic scripts that were later invented such as Idu, Gugyeol and Hyangchal. Mainly privileged elites were educated to read and write in Hanja. However, most of the population was illiterate.

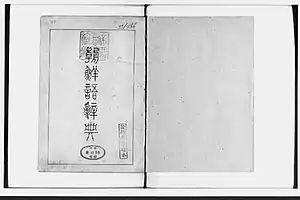

In the 15th century, King Sejong the Great personally developed an alphabetic featural writing system known today as Hangul.[6][7] He felt that Hanja was inadequate to write Korean and that this was the cause of its very restricted use; Hangul was designed to either aid in reading Hanja or replace Hanja entirely. Introduced in the document Hunminjeongeum, it was called eonmun (colloquial script) and quickly spread nationwide to increase literacy in Korea. Hangul was widely used by all the Korean classes, but often treated as amkeul ("script for women") and disregarded by privileged elites, whereas Hanja was regarded as jinseo ("true text"). Consequently, official documents were always written in Hanja during the Joseon era. Since most people couldn't understand Hanja, Korean kings sometimes released public notices entirely written in Hangul as early as the 16th century for all Korean classes, including uneducated peasants and slaves. By the 17th century, the elite class of Yangban exchanged Hangul letters with their slaves, suggesting a high literacy rate of Hangul during the Joseon era.[8]

Today, Hanja is largely unused in everyday life due to its inconvenience, but it is still important for historical and linguistic studies. Neither South Korea nor North Korea opposes the learning of Hanja, though they are not officially used in North Korea anymore, and their usage in South Korea is mainly reserved for specific circumstances, such as newspapers, scholarly papers, and disambiguation.

Names

The Korean names for the language are based on the names for Korea used in both South Korea and North Korea. The English word "Korean" is derived from Goryeo, which is thought to be the first Korean dynasty known to Western nations. Korean people in the former USSR refer to themselves as Koryo-saram and/or Koryo-in (literally, "Koryo/Goryeo person(s)"), and call the language Koryo-mal. Some older English sources also use the spelling "Corea" to refer to the nation, and its inflected form for the language, culture and people, "Korea" becoming more popular in the late 1800s.[9]

In South Korea, the Korean language is referred to by many names including hanguk-eo ("Korean language"), hanguk-mal ("Korean speech") and uri-mal ("our language"); "hanguk" is taken from the name of the Korean Empire (대한제국; 大韓帝國; Daehan Jeguk). The "han" (韓) in Hanguk and Daehan Jeguk is derived from Samhan, in reference to the Three Kingdoms of Korea (not the ancient confederacies in the southern Korean Peninsula),[10][11] while "-eo" and "-mal" mean "language" and "speech", respectively. Korean is also simply referred to as guk-eo, literally "national language". This name is based on the same Han characters (國語 "nation" + "language") that are also used in Taiwan and Japan to refer to their respective national languages.

In North Korea and China, the language is most often called Joseon-mal, or more formally, Joseon-o. This is taken from the North Korean name for Korea (Joseon), a name retained from the Joseon dynasty until the proclamation of the Korean Empire, which in turn was annexed by the Empire of Japan.

In mainland China, following the establishment of diplomatic relations with South Korea in 1992, the term Cháoxiǎnyǔ or the short form Cháoyǔ has normally been used to refer to the standard language of North Korea and Yanbian, whereas Hánguóyǔ or the short form Hányǔ is used to refer to the standard language of South Korea.

Classification

Korean is a member of the Koreanic family along with the Jeju language. Some linguists have included it in the Altaic family, but the core Altaic proposal itself has lost most of its prior support.[12] The Khitan language has several vocabulary items similar to Korean that are not found in other Mongolian or Tungusic languages, suggesting a Korean influence on Khitan.[13]

The hypothesis that Korean could be related to Japanese has had some supporters due to some overlap in vocabulary and similar grammatical features that have been elaborated upon by such researchers as Samuel E. Martin[14] and Roy Andrew Miller.[15] Sergei Anatolyevich Starostin (1991) found about 25% of potential cognates in the Japanese–Korean 100-word Swadesh list.[16] Some linguists concerned with the issue between Japanese and Korean, including Alexander Vovin, have argued that the indicated similarities are not due to any genetic relationship, but rather to a sprachbund effect and heavy borrowing, especially from Ancient Korean into Western Old Japanese.[17] A good example might be Middle Korean sàm and Japanese asá, meaning "hemp".[18] This word seems to be a cognate, but although it is well attested in Western Old Japanese and Northern Ryukyuan languages, in Eastern Old Japanese it only occurs in compounds, and it is only present in three dialects of the Southern Ryukyuan language group. Also, the doublet wo meaning "hemp" is attested in Western Old Japanese and Southern Ryukyuan languages. It is thus plausible to assume a borrowed term.[19] (See Classification of the Japonic languages or Comparison of Japanese and Korean for further details on a possible relationship.)

Hudson & Robbeets (2020) suggested that there are traces of a pre-Nivkh substratum in Korean. According to the hypothesis, ancestral varieties of Nivkh (also known as Amuric) were once distributed on the Korean peninsula before the arrival of Koreanic speakers.[20]

Phonology

Korean syllable structure is (C)(G)V(C), consisting of an optional onset consonant, glide /j, w, ɰ/ and final coda /p, t, k, m, n, ŋ, l/ surrounding a core vowel.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | ㅁ /m/ | ㄴ /n/ | ㅇ /ŋ/[upper-alpha 1] | |||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

plain | ㅂ /p/ | ㄷ /t/ | ㅈ /t͡s/ or /t͡ɕ/ | ㄱ /k/ | |

| tense | ㅃ /p͈/ | ㄸ /t͈/ | ㅉ /t͡s͈/ or /t͡ɕ͈/ | ㄲ /k͈/ | ||

| aspirated | ㅍ /pʰ/ | ㅌ /tʰ/ | ㅊ /t͡sʰ/ or /t͡ɕʰ/ | ㅋ /kʰ/ | ||

| Fricative | plain | ㅅ /s/ or /sʰ/ | ㅎ /h/ | |||

| tense | ㅆ /s͈/ | |||||

| Approximant | /w/[upper-alpha 2] | /j/[upper-alpha 2] | ||||

| Liquid | ㄹ /l/ or /ɾ/ | |||||

- only at the end of a syllable

- The semivowels /w/ and /j/ are represented in Korean writing by modifications to vowel symbols (see below).

Assimilation and allophony

The IPA symbol ⟨◌͈⟩ (a subscript double straight quotation mark, shown here with a placeholder circle) is used to denote the Tensed consonants /p͈/, /t͈/, /k͈/, /t͡ɕ͈/, /s͈/. Its official use in the Extensions to the IPA is for 'strong' articulation, but is used in the literature for faucalized voice. The Korean consonants also have elements of stiff voice, but it is not yet known how typical this is of faucalized consonants. They are produced with a partially constricted glottis and additional subglottal pressure in addition to tense vocal tract walls, laryngeal lowering, or other expansion of the larynx.

/s/ is aspirated [sʰ] and becomes an alveolo-palatal [ɕʰ] before [j] or [i] for most speakers (but see North–South differences in the Korean language). This occurs with the tense fricative and all the affricates as well. At the end of a syllable, /s/ changes to /t/ (example: beoseot (버섯) 'mushroom').

/h/ may become a bilabial [ɸ] before [o] or [u], a palatal [ç] before [j] or [i], a velar [x] before [ɯ], a voiced [ɦ] between voiced sounds, and a [h] elsewhere.

/p, t, t͡ɕ, k/ become voiced [b, d, d͡ʑ, ɡ] between voiced sounds.

/m, n/ frequently denasalize at the beginnings of words.

/l/ becomes alveolar flap [ɾ] between vowels, and [l] or [ɭ] at the end of a syllable or next to another /l/. Note that a written syllable-final 'ㄹ', when followed by a vowel or a glide (i.e., when the next character starts with 'ㅇ'), migrates to the next syllable and thus becomes [ɾ].

Traditionally, /l/ was disallowed at the beginning of a word. It disappeared before [j], and otherwise became /n/. However, the inflow of western loanwords changed the trend, and now word-initial /l/ (mostly from English loanwords) are pronounced as a free variation of either [ɾ] or [l]. The traditional prohibition of word-initial /l/ became a morphological rule called "initial law" (두음법칙) in South Korea, which pertains to Sino-Korean vocabulary. Such words retain their word-initial /l/ in North Korea.

All obstruents (plosives, affricates, fricatives) at the end of a word are pronounced with no audible release, [p̚, t̚, k̚].

Plosive sounds /p, t, k/ become nasals [m, n, ŋ] before nasal sounds.

Hangul spelling does not reflect these assimilatory pronunciation rules, but rather maintains the underlying, partly historical morphology. Given this, it is sometimes hard to tell which actual phonemes are present in a certain word.

One difference between the pronunciation standards of North and South Korea is the treatment of initial [ɾ], and initial [n]. For example,

- "labor" – north: rodong (로동), south: nodong (노동)

- "history" – north: ryeoksa (력사), south: yeoksa (역사)

- "female" – north: nyeoja (녀자), south: yeoja (여자)

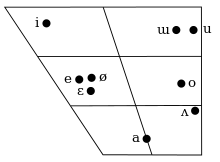

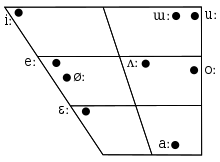

Vowels

| Monophthongs | ㅏ /a/NOTE ㅓ /ʌ/ ㅗ /o/ ㅜ /u/ ㅡ /ɯ/ ㅣ /i/ /e/ ㅔ, /ɛ/ ㅐ, /ø/ ㅚ, /y/ ㅟ |

|---|---|

| Vowels preceded by intermediaries, or diphthongs |

ㅑ /ja/ ㅕ /jʌ/ ㅛ /jo/ ㅠ /ju/ /je/ ㅖ, /jɛ/ ㅒ, /wi/ ㅟ, /we/ ㅞ, /wɛ/ ㅙ, /wa/ ㅘ, /ɰi/ ㅢ, /wə/ ㅝ |

^NOTE ㅏ is closer to a near-open central vowel ([ɐ]), though ⟨a⟩ is still used for tradition.

Morphophonemics

Grammatical morphemes may change shape depending on the preceding sounds. Examples include -eun/-neun (-은/-는) and -i/-ga (-이/-가).

Sometimes sounds may be inserted instead. Examples include -eul/-reul (-을/-를), -euro/-ro (-으로/-로), -eseo/-seo (-에서/-서), -ideunji/-deunji (-이든지/-든지) and -iya/-ya (-이야/-야).

- However, -euro/-ro is somewhat irregular, since it will behave differently after a ㄹ (rieul consonant).

| After a consonant | After a ㄹ (rieul) | After a vowel |

|---|---|---|

| -ui (-의) | ||

| -eun (-은) | -neun (-는) | |

| -i (-이) | -ga (-가) | |

| -eul (-을) | -reul (-를) | |

| -gwa (-과) | -wa (-와) | |

| -euro (-으로) | -ro (-로) | |

Some verbs may also change shape morphophonemically.

Grammar

Korean is an agglutinative language. The Korean language is traditionally considered to have nine parts of speech. Modifiers generally precede the modified words, and in the case of verb modifiers, can be serially appended. The sentence structure or basic form of a Korean sentence is subject–object–verb (SOV), but the verb is the only required and immovable element and word order is highly flexible, as in many other agglutinative languages.

| Question: | "Did [you] go to the store?" ("you" implied in conversation) | |||

| 가게에 | 가셨어요? | |||

| gage-e | ga-syeo-sseo-yo | |||

| store + [location marker (에)] | [go (verb root) (가)] + [honorific (시)] + [conjugated (contraction rule)(어)] + [past (ㅆ)] + [conjunctive (어)] + [polite marker (요)] | |||

| Response: | "Yes." | |

| 예. (or 네.) | ||

| ye (or ne) | ||

| yes | ||

The relationship between a speaker/writer and their subject and audience is paramount in Korean grammar. The relationship between the speaker/writer and subject referent is reflected in honorifics, whereas that between speaker/writer and audience is reflected in speech level.

Honorifics

When talking about someone superior in status, a speaker or writer usually uses special nouns or verb endings to indicate the subject's superiority. Generally, someone is superior in status if they are an older relative, a stranger of roughly equal or greater age, or an employer, teacher, customer, or the like. Someone is equal or inferior in status if they are a younger stranger, student, employee, or the like. Nowadays, there are special endings which can be used on declarative, interrogative, and imperative sentences, and both honorific or normal sentences.

Honorifics in traditional Korea were strictly hierarchical. The caste and estate systems possessed patterns and usages much more complex and stratified than those used today. The intricate structure of the Korean honorific system flourished in traditional culture and society. Honorifics in contemporary Korea are now used for people who are psychologically distant. Honorifics are also used for people who are superior in status. For example, older people, teachers, and employers.[21]

Speech levels

There are seven verb paradigms or speech levels in Korean, and each level has its own unique set of verb endings which are used to indicate the level of formality of a situation.[22] Unlike honorifics—which are used to show respect towards the referent (the person spoken of)—speech levels are used to show respect towards a speaker's or writer's audience (the person spoken to). The names of the seven levels are derived from the non-honorific imperative form of the verb 하다 (hada, "do") in each level, plus the suffix 체 ("che", Hanja: 體), which means "style".

The three levels with high politeness (very formally polite, formally polite, casually polite) are generally grouped together as jondaenmal (존댓말), whereas the two levels with low politeness (formally impolite, casually impolite) are banmal (반말) in Korean. The remaining two levels (neutral formality with neutral politeness, high formality with neutral politeness) are neither polite nor impolite.

Nowadays, younger-generation speakers no longer feel obligated to lower their usual regard toward the referent. It is common to see younger people talk to their older relatives with banmal (반말). This is not out of disrespect, but instead it shows the intimacy and the closeness of the relationship between the two speakers. Transformations in social structures and attitudes in today's rapidly changing society have brought about change in the way people speak.[21]

Gender

In general, Korean lacks grammatical gender. As one of the few exceptions, the third-person singular pronoun has two different forms: 그 geu (male) and 그녀 geunyeo (female). Before 그녀 was invented in need of translating 'she' into Korean, 그 was the only one third-person singular pronoun, and had no grammatical gender. Due to its origin 그녀 is never used in spoken Korean but only appears in writings.

In order to have a more complete understanding of intricacies of gender within the Korean language, we can look at the three models of language and gender that have been proposed: the deficit model, the dominance model, and the cultural difference model. In the deficit model, male speech is seen as the default, and any form of speech that diverges from this norm (female speech) is seen as lesser than. The dominance model sees women as lacking in power due to living within a patriarchal society. The cultural difference model proposes that the difference in upbringing between men and women can explain the differences in their speech patterns. It is important to look at these models so that one can better understand the misogynistic conditions that shaped the way men and women use the Korean language. Korean's lack of grammatical gender makes it different from most European languages. Rather, gendered differences in Korean can be observed through formality, intonation, word choice, etc.[23]

However, one can still find stronger contrasts between genders within Korean speech. Some examples of this can be seen in: (1) softer tone used by women in speech; (2) a married woman introducing herself as someone's mother or wife, not with her own name; (3) the presence of gender differences in titles and occupational terms (for example, a sajang is a company president and yŏsajang is a female company president.); (4) females sometimes using more tag questions and rising tones in statements, also seen in speech from children.[24]

Between two people of asymmetrical status in a Korean society, people tend to emphasize differences in status for the sake of solidarity. Koreans prefer to use kinship terms, rather than any other terms of reference.[25] In traditional Korean society, women have long been in disadvantaged positions. Korean social structure traditionally was a patriarchically dominated family system that emphasized the maintenance of family lines. This structure has tended to separate the roles of women from those of men.[26]

Cho and Whitman (2019) explain that the different categories like male and female in social conditions influence the Korean language features. What they noticed was the word "Jagi (자기)". Before explaining the word "Jagi (자기)", one thing that needs to be clearly distinguished is that "Jagi (자기)" can be used in a variety of situations, not all of which mean the same thing, but it depends on the context. Parallel variable solidarity and affection move the convention of speech style, especially terms of address that Jagi (자기 'you') has emerged as a gender-specific second-person pronoun used by women. However, unlike the preceding, young Koreans use the word "Jagi (자기)" to their lovers or spouses regardless of gender. Among middle-aged women, the word "Jagi (자기)" is sometimes used when calling someone who is close to them.

Korean society's prevalent attitude towards men being in public (outside the home) and women living in private still exists today. For instance, the word for husband is bakkat|yangban (바깥양반 'outside' 'nobleman') whereas a husband introduces his wife as an|saram (안사람 an 'inside' 'person'). Also in Kinship terminology, we (외 'outside' or 'wrong') is added for maternal grandparents, creating we-harabeoji and we-hal-meoni (외할아버지, 외할머니 'grandfather and grandmother'), differentiating lexicons for males and females, revealing patriarchal society. Further, in interrogatives to an addressee of equal or lower status, Korean men tend to use 'haetnya (했냐? 'did it?’)' in aggressive masculinity, whereas women use 'haetni (했니? 'did it?’)' as a soft expression.[27] However, not all of the foregoing are always correct. If we observe how Korean society used the question endings '-ni (니)' and '-nya (냐)', the ending '-ni (니)' prevailed not only among women but also among men until a few decades ago. In fact, '-nya (냐)' was characteristic of Jeolla and Chungcheong dialects. However, since the 1950s, large numbers of people have moved to Seoul from Chungcheong and Jeolla, and as a result, they began to influence the way men speak. Recently, women also use the term '-nya (냐)'. To sum up, in the case of '-ni (니)', even if one is not close or younger than yourself, it is usually used for people who need to be polite, and in the case of '-nya (냐)', it is used mainly for close friends regardless of gender.

Like the case of "actor" and "actress," it also is possible to add a gender prefix to emphasize: biseo (비서 'secretary') sometimes is combined with yeo (여 'female') to form yeo-biseo (여비서 'female secretary'); namja (남자 'man') often is added to ganhosa (간호사 'nurse') for the base word to be namja-ganhosa (남자간호사 'male nurse') to indicate a male nurse. Note that this isn't a matter of whether or not to omit; it's about addition. Words without those prefixes don't sound awkward at all nor do they remind listeners of political correctness.

Another crucial difference between genders of men and women is the tone and pitch of their voices and how that affects the perception of politeness. Upspeak Men learn to use an authoritative falling tone, and in Korean culture a deeper voice is associated with being more polite. In addition to the deferential speech endings being used, men are seen as more polite as well as impartial and professional. When compared to women who use a rising tone in conjunction with the -yo (요) ending, they are not perceived to be as polite as men. The -yo (요) ending also indicates uncertainty due to how this ending has many prefixes which indicate uncertainty and questioning. While the deferential ending does not have any prefixes which can indicate uncertainty. The -hapnida (합니다) ending is the most polite and formal form of Korea, while the -yo (요) ending is less polite and formal which is where the perception of women being less professional originates from.[27][28]

Hedges soften an assertion and its function as a euphemism in women's speech in terms of discourse difference. Women are expected to add nasal sounds, neyng, neym, ney-ey, more frequently than men at the last syllable. The sound L is often added in women's for female stereotypes that igeolo (이거로 'this thing') become igeollo (이걸로 'this thing') to refer a lack of confidence and passive construction.[21]

Women use more linguistic markers such as exclamation eomeo (어머 'oh') and eojjeom (어쩜 'what a surprise') to cooperative communication.[27]

Vocabulary

The core of the Korean vocabulary is made up of native Korean words. However, a significant proportion of the vocabulary, especially words that denote abstract ideas, are Sino-Korean words (of Chinese origin).[29] To a much lesser extent, some words have also been borrowed from Mongolian and other languages.[30] More recent loanwords are dominated by English.

North Korean vocabulary shows a tendency to prefer native Korean over Sino-Korean or foreign borrowings, especially with recent political objectives aimed at eliminating foreign influences on the Korean language in the North. In the early years, the North Korean government tried to eliminate Sino-Korean words. Consequently, South Korean may have several Sino-Korean or foreign borrowings which are not in North Korean.

| Number | Sino-Korean cardinals | Native Korean cardinals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangul | Romanization | Hangul | Romanization | |

| 1 | 일 | il | 하나 | hana |

| 2 | 이 | i | 둘 | dul |

| 3 | 삼 | sam | 셋 | set |

| 4 | 사 | sa | 넷 | net |

| 5 | 오 | o | 다섯 | daseot |

| 6 | 육, 륙 | yuk, ryuk | 여섯 | yeoseot |

| 7 | 칠 | chil | 일곱 | ilgop |

| 8 | 팔 | pal | 여덟 | yeodeol |

| 9 | 구 | gu | 아홉 | ahop |

| 10 | 십 | sip | 열 | yeol |

Sino-Korean

Sino-Korean vocabulary consists of:

- words directly borrowed from written Chinese, and

- compounds coined in Korea or Japan and read using the Sino-Korean reading of Chinese characters.

Therefore, just like other words, Korean has two sets of numeral systems. English is similar, having native English words and Latinate equivalents such as water-aqua, fire-flame, sea-marine, two-dual, sun-solar, star-stellar. However, unlike English and Latin which belong to the same Indo-European languages family and bear a certain resemblance, Korean and Chinese are genetically unrelated and the two sets of Korean words differ completely from each other. All Sino-Korean morphemes are monosyllabic as in Chinese, whereas native Korean morphemes can be polysyllabic. The Sino-Korean words were deliberately imported alongside corresponding Chinese characters for a written language and everything was supposed to be written in Hanja, so the coexistence of Sino-Korean would be more thorough and systematic than that of Latinate words in English.

The exact proportion of Sino-Korean vocabulary is a matter of debate. Sohn (2001) stated 50–60%.[29] In 2006 the same author gives an even higher estimate of 65%.[31] Jeong Jae-do, one of the compilers of the dictionary Urimal Keun Sajeon, asserts that the proportion is not so high. He points out that Korean dictionaries compiled during the colonial period include many unused Sino-Korean words. In his estimation, the proportion of Sino-Korean vocabulary in the Korean language might be as low as 30%.[32]

Western loanwords

The vast majority of loanwords other than Sino-Korean come from modern times, approximately 90% of which are from English.[29] Many words have also been borrowed from Western languages such as German via Japanese (아르바이트 (areubaiteu) "part-time job", 알레르기 (allereugi) "allergy", 기브스 (gibseu or gibuseu) "plaster cast used for broken bones"). Some Western words were borrowed indirectly via Japanese during the Japanese occupation of Korea, taking a Japanese sound pattern, for example "dozen" > ダース dāsu > 다스 daseu. Most indirect Western borrowings are now written according to current "Hangulization" rules for the respective Western language, as if borrowed directly. There are a few more complicated borrowings such as "German(y)" (see names of Germany), the first part of whose endonym Deutschland [ˈdɔʏtʃlant] the Japanese approximated using the kanji 獨逸 doitsu that were then accepted into the Korean language by their Sino-Korean pronunciation: 獨 dok + 逸 il = Dogil. In South Korean official use, a number of other Sino-Korean country names have been replaced with phonetically oriented "Hangeulizations" of the countries' endonyms or English names.

Because of such a prevalence of English in modern South Korean culture and society, lexical borrowing is inevitable. English-derived Korean, or "Konglish" (콩글리쉬), is increasingly used. The vocabulary of the South Korean dialect of the Korean language is roughly 5% loanwords (excluding Sino-Korean vocabulary).[33] However, due to North Korea's isolation, such influence is lacking in North Korean speech.

Korean uses words adapted from English in ways that may seem strange or unintuitive to native English speakers. For example, fighting (화이팅 / 파이팅 hwaiting / paiting) is a term of encouragement, like 'come on'/'go (on)' in English. Something that is 'service' (서비스 seobiseu) is free or 'on the house'. A building referred to as an 'apart' (아파트 apateu) is an 'apartment' (but in fact refers to a residence more akin to a condominium) and a type of pencil that is called a 'sharp' (샤프) is a mechanical pencil. Like other borrowings, many of these idiosyncrasies, including all the examples listed above, appear to be imported into Korean via Japanese, or influenced by Japanese. Many English words introduced via Japanese pronunciation have been reformed, as in 멜론 (melon) which was once called 메론 (meron) as in Japanese.

There are also several words derived from nouns used to describe western culture. "kokain" ({코카인}), for example, is a Korean term used to describe younger Caucasian females. It is a reference to the drug "cocaine", because of their lighter skin, as it shares the same spelling and pronunciation. Other words can also be used the other way, such as calling a friend a ({양키} "yangki") or "Yankee" for their bold or western-styled personality.

Writing system

.jpg.webp) |

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

| Chosŏn'gŭl (in North Korea) |

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

|

| Transliteration |

|

Before the creation of the modern Korean alphabet, known as Chosŏn'gŭl in North Korea and as Hangul in South Korea, people in Korea (known as Joseon at the time) primarily wrote using Classical Chinese alongside native phonetic writing systems that predate Hangul by hundreds of years, including idu, hyangchal, gugyeol, and gakpil.[34][35][36][37] However, due to the fundamental differences between the Korean and Chinese languages and the large number of characters to be learned, the lower classes, who often didn't have the privilege of education, had much difficulty in learning how to write using Chinese characters. To assuage this problem, King Sejong (r. 1418–1450) created the unique alphabet known as Hangul to promote literacy among the common people.[38]

The Korean alphabet was denounced and looked down upon by the yangban aristocracy, who deemed it too easy to learn,[39][40] but it gained widespread use among the common class[41] and was widely used to print popular novels which were enjoyed by the common class.[42] With growing Korean nationalism in the 19th century, the Gabo Reformists' push, and the promotion of Hangul in schools,[43] in 1894, Hangul displaced Hanja as Korea's national script.[44] Hanja are still used to a certain extent in South Korea, where they are sometimes combined with Hangul, but this method is slowly declining in use, even though students learn Hanja in school.[45]

Symbol chart

Below is a chart of the Korean alphabet's (Hangul) symbols and their Revised Romanization (RR) and canonical International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) values:

| Hangul 한글 | ㅂ | ㄷ | ㅈ | ㄱ | ㅃ | ㄸ | ㅉ | ㄲ | ㅍ | ㅌ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅅ | ㅎ | ㅆ | ㅁ | ㄴ | ㅇ | ㄹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | b | d | j | g | pp | tt | jj | kk | p | t | ch | k | s | h | ss | m | n | ng | r, l |

| IPA | p | t | t͡ɕ | k | p͈ | t͈ | t͡ɕ͈ | k͈ | pʰ | tʰ | t͡ɕʰ | kʰ | s | h | s͈ | m | n | ŋ | ɾ, l |

| Hangul 한글 | ㅣ | ㅔ | ㅚ | ㅐ | ㅏ | ㅗ | ㅜ | ㅓ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅖ | ㅒ | ㅑ | ㅛ | ㅠ | ㅕ | ㅟ | ㅞ | ㅙ | ㅘ | ㅝ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | i | e | oe | ae | a | o | u | eo | eu | ui | ye | yae | ya | yo | yu | yeo | wi | we | wae | wa | wo |

| IPA | i | e | ø, we | ɛ | a | o | u | ʌ | ɯ | ɰi | je | jɛ | ja | jo | ju | jʌ | ɥi, wi | we | wɛ | wa | wʌ |

The letters of the Korean alphabet are not written linearly like most alphabets, but instead arranged into blocks that represent syllables. So, while the word bibimbap (Korean rice dish) is written as eight characters in a row in the Latin alphabet, in Korean it is written 비빔밥, as three "syllabic blocks" in a row. Mukbang (먹방 'eating show') is seven characters after romanization but only two "syllabic blocks" before.

Modern Korean is written with spaces between words, a feature not found in Chinese or Japanese (except when Japanese is written exclusively in hiragana, as in children's books). The marks used for Korean punctuation are almost identical to Western ones. Traditionally, Korean was written in columns, from top to bottom, right to left, like traditional Chinese. However, the syllabic blocks are now usually written in rows, from left to right, top to bottom, like English.

Dialects

Korean has numerous small local dialects (called mal (말) [literally 'speech'], saturi (사투리), or bang'eon (방언). The standard language (pyojun-eo or pyojun-mal) of both South Korea and North Korea is based on the dialect of the area around Seoul (which, as Hanyang, was the capital of Joseon-era Korea for 500 years), though the northern standard after the Korean War has been influenced by the dialect of P'yŏngyang. All dialects of Korean are similar to each other and largely mutually intelligible (with the exception of dialect-specific phrases or non-Standard vocabulary unique to dialects), though the dialect of Jeju Island is divergent enough to be sometimes classified as a separate language.[46][47][48] One of the more salient differences between dialects is the use of tone: speakers of the Seoul dialect make use of vowel length, whereas speakers of the Gyeongsang dialect maintain the pitch accent of Middle Korean. Some dialects are conservative, maintaining Middle Korean sounds (such as z, β, ə) which have been lost from the standard language, whereas others are highly innovative.

Kang Yoon-jung et al. (2013),[49] Kim Mi-ryoung (2013),[50] and Cho Sung-hye (2017)[51] suggest that the modern Seoul dialect is currently undergoing tonogenesis, based on the finding that in recent years lenis consonants (ㅂㅈㄷㄱ), aspirated consonants (ㅍㅊㅌㅋ) and fortis consonants (ㅃㅉㄸㄲ) were shifting from a distinction via voice onset time to that of pitch change; however, Choi Ji-youn et al. (2020) disagree with the suggestion that the consonant distinction shifting away from voice onset time is due to the introduction of tonal features, and instead proposes that it is a prosodically-conditioned change.[52]

There is substantial evidence for a history of extensive dialect levelling, or even convergent evolution or intermixture of two or more originally distinct linguistic stocks, within the Korean language and its dialects. Many Korean dialects have basic vocabulary that is etymologically distinct from vocabulary of identical meaning in Standard Korean or other dialects, for example "garlic chives" translated into Gyeongsang dialect /t͡ɕʌŋ.ɡu.d͡ʑi/ (정구지; jeongguji) but in Standard Korean, it is /puːt͡ɕʰu/ (부추; buchu). This suggests that the Korean Peninsula may have at one time been much more linguistically diverse than it is at present.[53] See also the Japanese–Koguryoic languages hypothesis.

Nonetheless, the separation of the two Korean states has resulted in increasing differences among the dialects that have emerged over time. Since the allies of the newly founded nations split the Korean peninsula in half after 1945, the newly formed Korean nations have since borrowed vocabulary extensively from their respective allies. As the Soviet Union helped industrialize North Korea and establish it as a communist state, the North Koreans therefore borrowed a number of Russian terms. Likewise, since the United States helped South Korea extensively to develop militarily, economically, and politically, South Koreans therefore borrowed extensively from English.

The differences among northern and southern dialects have become so significant that many North Korean defectors reportedly have had great difficulty communicating with South Koreans after having initially settled into South Korea. In response to the diverging vocabularies, an app called Univoca was designed to help North Korean defectors learn South Korean terms by translating them into North Korean ones.[54] More information can be found on the page North-South differences in the Korean language.

Aside from the standard language, there are few clear boundaries between Korean dialects, and they are typically partially grouped according to the regions of Korea.[55][56]

Recently, both North and South Korea's usage rate of the regional dialect have been decreasing due to social factors. In North Korea, the central government is urging its citizens to use Munhwaŏ (the standard language of North Korea), to deter the usage of foreign language and Chinese characters: Kim Jong-un said in a speech "if your language in life is cultural and polite, you can achieve harmony and comradely unity among people."[57] In South Korea, due to relocation in the population to Seoul to find jobs and the usage of standard language in education and media, the prevalence of regional dialects has decreased.[58] Moreover, internationally, due to the increasing popularity of K-pop, the Seoul standard language has become more widely taught and used.

| Standard language | Locations of use | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyojuneo (표준어) | Standard language of ROK. Based on Seoul dialect; very similar to Incheon and most of Gyeonggi, west of Gangwon-do (Yeongseo region); also commonly used among younger Koreans nationwide and in online context. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Munhwaŏ (문화어) | Standard language of DPRK. Based on Seoul dialect and P'yŏngan dialect.[59] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regional dialects | Locations of use and example compared to the standard language | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hamgyŏng/Northeastern (함경/동북) |

Rasŏn, most of Hamgyŏng region, northeast P'yŏngan, Ryanggang Province (North Korea), Jilin (China).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| P'yŏngan/Northwestern (평안/서북) |

P'yŏngan region, P'yŏngyang, Chagang, northern North Hamgyŏng (North Korea), Liaoning (China)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hwanghae/Central (황해/중부) |

Hwanghae region (North Korea). Also in the Islands of Yeonpyeongdo, Baengnyeongdo and Daecheongdo in Ongjin County of Incheon.

Areas in Northwest Hwanghae, such as Ongjin County in Hwanghae Province, pronounced 'ㅈ' (j'), originally pronounced the letter more closely to tz. However, this has largely disappeared. The rest is almost similar to the Gyeonggi and Pyongan dialect. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gyeonggi/Central (경기/중부) |

Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi region (South Korea), as well as Kaeseong, Gaepoong and Changpung in North Korea.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gangwon<Yeongseo/Yeongdong>/Central (강원<영서/영동>/중부) |

Yeongseo (Gangwon (South Korea)/Kangwŏn (North Korea) west of the Taebaek Mountains), Yeongdong (Gangwon (South Korea)/Kangwŏn (North Korea), east of the Taebaek Mountains)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chungcheong/Central (충청/중부) |

Daejeon, Sejong, Chungcheong region (South Korea)

The rest is almost similar to the Gyeonggi dialect. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jeolla/Southwestern (전라/서남) |

Gwangju, Jeolla region (South Korea)

Famously, natives of Southern Jeolla pronounce certain combinations of vowels in Korean more softly, or omit the latter vowel entirely.

However, in the case of '모대(modae)', it is also observed in South Chungcheong Province and some areas of southern Gyeonggi Province close to South Chungcheong Province. The rest is almost similar to the Chungcheong dialect. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gyeongsang/Southeastern (경상/동남) |

Busan, Daegu, Ulsan, Gyeongsang region (South Korea)

The rest is almost similar to the Jeolla dialect. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jeju (제주)* | Jeju Island/Province (South Korea); sometimes classified as a separate language in the Koreanic language family

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

North–South differences

The language used in the North and the South exhibit differences in pronunciation, spelling, grammar and vocabulary.[64]

Pronunciation

In North Korea, palatalization of /si/ is optional, and /t͡ɕ/ can be pronounced [z] between vowels.

Words that are written the same way may be pronounced differently (such as the examples below). The pronunciations below are given in Revised Romanization, McCune–Reischauer and modified Hangul (what the Korean characters would be if one were to write the word as pronounced).

| Word | RR | Meaning | Pronunciation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | South | |||||||

| RR | MR | Chosungul | RR | MR | Hangul | |||

| 읽고 | ilgo | to read (continuative form) | ilko | ilko | (일)코 | ilkko | ilkko | (일)꼬 |

| 압록강 | amnokgang | Amnok River | amrokgang | amrokkang | 암(록)깡 | amnokkang | amnokkang | 암녹깡 |

| 독립 | dongnip | independence | dongrip | tongrip | 동(립) | dongnip | tongnip | 동닙 |

| 관념 | gwannyeom | idea / sense / conception | gwallyeom | kwallyŏm | 괄렴 | gwannyeom | kwannyŏm | (관)념 |

| 혁신적* | hyeoksinjeok | innovative | hyeoksinjjeok | hyŏksintchŏk | (혁)씬쩍 | hyeoksinjeok | hyŏksinjŏk | (혁)씬(적) |

* In the North, similar pronunciation is used whenever the hanja "的" is attached to a Sino-Korean word ending in ㄴ, ㅁ or ㅇ.

* In the South, this rule only applies when it is attached to any single-character Sino-Korean word.

Spelling

Some words are spelled differently by the North and the South, but the pronunciations are the same.

| Word | Meaning | Pronunciation (RR/MR) | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | South spelling | |||

| 해빛 | 햇빛 | sunshine | haeppit (haepit) | The "sai siot" ('ㅅ' used for indicating sound change) is almost never written out in the North. |

| 벗꽃 | 벚꽃 | cherry blossom | beotkkot (pŏtkkot) | |

| 못읽다 | 못 읽다 | cannot read | modikda (modikta) | Spacing. |

| 한나산 | 한라산 | Hallasan | hallasan (hallasan) | When a ㄴㄴ combination is pronounced as ll, the original Hangul spelling is kept in the North, whereas the Hangul is changed in the South. |

| 규률 | 규율 | rules | gyuyul (kyuyul) | In words where the original hanja is spelt "렬" or "률" and follows a vowel, the initial ㄹ is not pronounced in the North, making the pronunciation identical with that in the South where the ㄹ is dropped in the spelling. |

Spelling and pronunciation

Some words have different spellings and pronunciations in the North and the South. Most of the official languages of North Korea are from the northwest (Pyeongan dialect), and the standard language of South Korea is the standard language (Seoul language close to Gyeonggi dialect). some of which were given in the "Phonology" section above:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 력량 | ryeongryang (ryŏngryang) | 역량 | yeongnyang (yŏngnyang) | strength | Initial r's are dropped if followed by i or y in the South Korean version of Korean. |

| 로동 | rodong (rodong) | 노동 | nodong (nodong) | work | Initial r's are demoted to an n if not followed by i or y in the South Korean version of Korean. |

| 원쑤 | wonssu (wŏnssu) | 원수 | wonsu (wŏnsu) | mortal enemy | "Mortal enemy" and "field marshal" are homophones in the South. Possibly to avoid referring to Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il or Kim Jong-un as the enemy, the second syllable of "enemy" is written and pronounced 쑤 in the North.[65] |

| 라지오 | rajio (rajio) | 라디오 | radio (radio) | radio | |

| 우 | u (u) | 위 | wi (wi) | on; above | |

| 안해 | anhae (anhae) | 아내 | anae (anae) | wife | |

| 꾸바 | kkuba (kkuba) | 쿠바 | kuba (k'uba) | Cuba | When transcribing foreign words from languages that do not have contrasts between aspirated and unaspirated stops, North Koreans generally use tensed stops for the unaspirated ones while South Koreans use aspirated stops in both cases. |

| 페 | pe (p'e) | 폐 | pye (p'ye), pe (p'e) | lungs | In the case where ye comes after a consonant, such as in hye and pye, it is pronounced without the palatal approximate. North Korean orthography reflects this pronunciation nuance. |

In general, when transcribing place names, North Korea tends to use the pronunciation in the original language more than South Korea, which often uses the pronunciation in English. For example:

| Original name | North Korea transliteration | English name | South Korea transliteration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spelling | Pronunciation | Spelling | Pronunciation | ||

| Ulaanbaatar | 울란바따르 | ullanbattareu (ullanbattarŭ) | Ulan Bator | 울란바토르 | ullanbatoreu (ullanbat'orŭ) |

| København | 쾨뻰하븐 | koeppenhabeun (k'oeppenhabŭn) | Copenhagen | 코펜하겐 | kopenhagen (k'op'enhagen) |

| al-Qāhirah | 까히라 | kkahira (kkahira) | Cairo | 카이로 | kairo (k'airo) |

Grammar

Some grammatical constructions are also different:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 되였다 | doeyeotda (toeyŏtta) | 되었다 | doeeotda (toeŏtta) | past tense of 되다 (doeda/toeda), "to become" | All similar grammar forms of verbs or adjectives that end in ㅣ in the stem (i.e. ㅣ, ㅐ, ㅔ, ㅚ, ㅟ and ㅢ) in the North use 여 instead of the South's 어. |

| 고마와요 | gomawayo (komawayo) | 고마워요 | gomawoyo (komawŏyo) | thanks | ㅂ-irregular verbs in the North use 와 (wa) for all those with a positive ending vowel; this only happens in the South if the verb stem has only one syllable. |

| 할가요 | halgayo (halkayo) | 할까요 | halkkayo (halkkayo) | Shall we do? | Although the Hangul differ, the pronunciations are the same (i.e. with the tensed ㄲ sound). |

Punctuation

In the North, guillemets (《 and 》) are the symbols used for quotes; in the South, quotation marks equivalent to the English ones (" and ") are standard (although 『 』 and 「 」 are also used).

Vocabulary

Some vocabulary is different between the North and the South:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North word | North pronun. | South word | South pronun. | ||

| 문화주택 | munhwajutaek (munhwajut'aek) | 아파트 | apateu (ap'at'ŭ) | Apartment | 아빠트 (appateu/appat'ŭ) is also used in the North. |

| 조선말 | joseonmal (chosŏnmal) | 한국어 | han-guk'eo (han-guk'ŏ) | Korean language | The Japanese pronunciation of 조선말 was used throughout Korea and Manchuria during Japanese Imperial Rule, but after liberation, the government chose the name 대한민국 (Daehanminguk) which was derived from the name immediately prior to Japanese Imperial Rule. The syllable 한 (Han) was drawn from the same source as that name (in reference to the Han people). Read more. |

| 곽밥 | gwakbap (kwakpap) | 도시락 | dosirak (tosirak) | lunch box | |

| 동무 | dongmu (tongmu) | 친구 | chin-gu (ch'in-gu) | Friend | 동무 was originally a non-ideological word for "friend" used all over the Korean peninsula, but North Koreans later adopted it as the equivalent of the Communist term of address "comrade". As a result, to South Koreans today the word has a heavy political tinge, and so they have shifted to using other words for friend like chingu (친구) or beot (벗). South Koreans use chingu (친구) more often than beot (벗).

Such changes were made after the Korean War and the ideological battle between the anti-Communist government in the South and North Korea's communism.[66][67] |

Geographic distribution

Korean is spoken by the Korean people in both South Korea and North Korea, and by the Korean diaspora in many countries including the People's Republic of China, the United States, Japan, and Russia. Currently, Korean is the fourth most popular foreign language in China, following English, Japanese, and Russian.[68] Korean-speaking minorities exist in these states, but because of cultural assimilation into host countries, not all ethnic Koreans may speak it with native fluency.

Official status

Korean is the official language of South Korea and North Korea. It, along with Mandarin Chinese, is also one of the two official languages of China's Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture.

In North Korea, the regulatory body is the Language Institute of the Academy of Social Sciences (사회과학원 어학연구소; 社會科學院語學硏究所, Sahoe Gwahagweon Eohag Yeonguso). In South Korea, the regulatory body for Korean is the Seoul-based National Institute of the Korean Language, which was created by presidential decree on 23 January 1991.

King Sejong Institute

Established pursuant to Article 9, Section 2, of the Framework Act on the National Language, the King Sejong Institute[69] is a public institution set up to coordinate the government's project of propagating Korean language and culture; it also supports the King Sejong Institute, which is the institution's overseas branch. The King Sejong Institute was established in response to:

- An increase in the demand for Korean language education;

- a rapid increase in Korean language education thanks to the spread of the culture (hallyu), an increase in international marriage, the expansion of Korean enterprises into overseas markets, and enforcement of employment licensing system;

- the need for a government-sanctioned Korean language educational institution;

- the need for general support for overseas Korean language education based on a successful domestic language education program.

TOPIK Korea Institute

The TOPIK Korea Institute is a lifelong educational center affiliated with a variety of Korean universities in Seoul, South Korea, whose aim is to promote Korean language and culture, support local Korean teaching internationally, and facilitate cultural exchanges.

The institute is sometimes compared to language and culture promotion organizations such as the King Sejong Institute. Unlike that organization, however, the TOPIK Korea Institute operates within established universities and colleges around the world, providing educational materials. In countries around the world, Korean embassies and cultural centers (한국문화원) administer TOPIK examinations.[70]

As a foreign language

For native English speakers, Korean is generally considered to be one of the most difficult foreign languages to master despite the relative ease of learning Hangul. For instance, the United States' Defense Language Institute places Korean in Category IV with Japanese, Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese), and Arabic, requiring 64 weeks of instruction (as compared to just 26 weeks for Category I languages like Italian, French, and Spanish) to bring an English-speaking student to a limited working level of proficiency in which they have "sufficient capability to meet routine social demands and limited job requirements" and "can deal with concrete topics in past, present, and future tense."[71][72] Similarly, the Foreign Service Institute's School of Language Studies places Korean in Category IV, the highest level of difficulty.[73]

The study of the Korean language in the United States is dominated by Korean American heritage language students; in 2007 they were estimated to form over 80% of all students of the language at non-military universities.[74] However, Sejong Institutes in the United States have noted a sharp rise in the number of people of other ethnic backgrounds studying Korean between 2009 and 2011; they attribute this to rising popularity of South Korean music and television shows.[75] In 2018 it was reported that the rise in K-Pop was responsible for the increase in people learning the language in US universities.[76]

Testing

There are two widely used tests of Korean as a foreign language: the Korean Language Proficiency Test (KLPT) and the Test of Proficiency in Korean (TOPIK). The Korean Language Proficiency Test, an examination aimed at assessing non-native speakers' competence in Korean, was instituted in 1997; 17,000 people applied for the 2005 sitting of the examination.[77] The TOPIK was first administered in 1997 and was taken by 2,274 people. Since then the total number of people who have taken the TOPIK has surpassed 1 million, with more than 150,000 candidates taking the test in 2012.[78] TOPIK is administered in 45 regions within South Korea and 72 nations outside of South Korea, with a significant portion being administered in Japan and North America, which would suggest the targeted audience for TOPIK is still primarily foreigners of Korean heritage.[79] This is also evident in TOPIK's website, where the examination is introduced as intended for Korean heritage students.

See also

- Outline of Korean language

- Korean count word

- Korean Cultural Center (KCC)

- Korean dialects

- Korean language and computers

- Korean mixed script

- Korean particles

- Korean proverbs

- Korean sign language

- Korean romanization

- McCune–Reischauer

- Revised romanization of Korean

- SKATS

- Yale romanization of Korean

- List of English words of Korean origin

- Vowel harmony

- History of Korean

- Korean films

- Cinema of South Korea

- Cinema of North Korea

Notes

- Measured as of 2020. The estimated 2020 combined population of North and South Korea was about 77 million.

References

- Korean language at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

- Hölzl, Andreas (29 August 2018). A typology of questions in Northeast Asia and beyond: An ecological perspective. Language Science Press. p. 25. ISBN 9783961101023.

- Janhunen, Juha (2010). "Reconstructing the Language Map of Prehistorical Northeast Asia". Studia Orientalia (108).

... there are strong indications that the neighbouring Baekje state (in the southwest) was predominantly Japonic-speaking until it was linguistically Koreanized.

- Vovin, Alexander (2013). "From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean". Korean Linguistics. 15 (2): 222–240. doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.03vov.

- Whitman, John (1 December 2011). "Northeast Asian Linguistic Ecology and the Advent of Rice Agriculture in Korea and Japan". Rice. 4 (3): 149–158. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9080-0. ISSN 1939-8433.

- Kim-Renaud, Young-Key (1997). The Korean Alphabet: Its History and Structure. University of Hawaii Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780824817237. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "알고 싶은 한글". 국립국어원 (in Korean). National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Archive of Joseon's Hangul letters – A letter sent from Song Gyuryeom to slave Guityuk (1692)".

- According to Google's NGram English corpus of 2015, "Google Ngram Viewer".

- 이기환 (30 August 2017). "[이기환의 흔적의 역사]국호논쟁의 전말…대한민국이냐 고려공화국이냐". 경향신문 (in Korean). The Kyunghyang Shinmun. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- 이덕일. "[이덕일 사랑] 대~한민국". 조선닷컴 (in Korean). The Chosun Ilbo. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Cho & Whitman (2020), pp. 11–12.

- Vovin, Alexander (June 2017). "Koreanic loanwords in Khitan and their importance in the decipherment of the latter" (PDF). Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 70 (2): 207–215. doi:10.1556/062.2017.70.2.4.

- Martin (1966), Martin (1990)

- e.g. Miller (1971), Miller (1996)

- Starostin, Sergei (1991). Altaiskaya problema i proishozhdeniye yaponskogo yazika [The Altaic Problem and the Origins of the Japanese Language] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Vovin (2008).

- Whitman (1985), p. 232, also found in Martin (1966), p. 233

- Vovin (2008), pp. 211–212.

- Hudson, Mark J.; Robbeets, Martine (2020). "Archaeolinguistic Evidence for the Farming/Language Dispersal of Koreanic". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2. e52. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.49.

- Sohn (2006).

- Choo, Miho (2008). Using Korean: A Guide to Contemporary Usage. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-139-47139-8.

- Cho (2006), p. 189.

- Cho (2006), pp. 189–198.

- Kim, Minju (1999). "Cross Adoption of language between different genders: The case of the Korean kinship terms hyeng and enni". Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Women and Language Conference. Berkeley: Berkeley Women and Language Group.

- Palley, Marian Lief (December 1990). "Women's Status in South Korea: Tradition and Change". Asian Survey. 30 (12): 1136–1153. doi:10.2307/2644990. JSTOR 2644990.

- Brown (2015).

- Cho (2006), pp. 193–195.

- Sohn (2001), Section 1.5.3 "Korean vocabulary", pp. 12–13

- Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 6.

- Sohn (2006), p. 5.

- Kim, Jin-su (11 September 2009). 우리말 70%가 한자말? 일제가 왜곡한 거라네 [Our language is 70% hanja? Japanese Empire distortion]. The Hankyoreh (in Korean). Retrieved 11 September 2009. The dictionary mentioned is 우리말 큰 사전. Seoul: Hangul Hakhoe. 1992. OCLC 27072560.

- Sohn (2006), p. 87.

- Hannas, Wm C. (1997). Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. University of Hawaii Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- Chen, Jiangping (18 January 2016). Multilingual Access and Services for Digital Collections. ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4408-3955-9. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- "Invest Korea Journal". Invest Korea Journal. Vol. 23. Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency. 1 January 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

They later devised three different systems for writing Korean with Chinese characters: Hyangchal, Gukyeol and Idu. These systems were similar to those developed later in Japan and were probably used as models by the Japanese.

- "Korea Now". The Korea Herald. Vol. 29. 1 July 2000. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- Koerner, E. F. K.; Asher, R. E. (28 June 2014). Concise History of the Language Sciences: From the Sumerians to the Cognitivists. Elsevier. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4832-9754-5. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Montgomery, Charles (19 January 2016). "Korean Literature in Translation – CHAPTER FOUR: IT ALL CHANGES! THE CREATION OF HANGUL". ktlit.com. KTLit. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

Hangul was sometimes known as the "language of the inner rooms," (a dismissive term used partly by yangban in an effort to marginalize the alphabet), or the domain of women.

- Chan, Tak-hung Leo (2003). One into Many: Translation and the Dissemination of Classical Chinese Literature. Rodopi. p. 183. ISBN 978-9042008151. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- "Korea Newsreview". Korea News Review. Korea Herald, Incorporated. 1 January 1994. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Lee, Kenneth B. (1997). Korea and East Asia: The Story of a Phoenix. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-275-95823-7. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Silva, David J. (2008). "Missionary Contributions toward the Revaluation of Han'geul in Late 19th Century Korea" (PDF). International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2008 (192): 57–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.527.8160. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2008.035. S2CID 43569773. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- "Korean History". Korea.assembly.go.kr. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

Korean Empire, Edict No. 1 – All official documents are to be written in Hangul, and not Chinese characters.

- "현판 글씨들이 한글이 아니라 한자인 이유는?". royalpalace.go.kr (in Korean). Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Source: Unescopress. "New interactive atlas adds two more endangered languages | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". Unesco.org. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- Lightfoot, David (12 January 1999). Development of Language. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-21059-7.

- Janhunen, Juha (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. Finno-Ugrian Society. ISBN 978-951-9403-84-7.

- Kang, Yoonjung; Han, Sungwoo (September 2013). "Tonogenesis in early Contemporary Seoul Korean: A longitudinal case study". Lingua. 134: 62–74. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2013.06.002.

- Kim, Mi-Ryoung (2013). "Tonogenesis in contemporary Korean with special reference to the onset-tone interaction and the loss of a consonant opposition". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 133 (3570): 3570. Bibcode:2013ASAJ..133.3570K. doi:10.1121/1.4806535.

- Cho, Sunghye (2017). Development of pitch contrast and Seoul Korean intonation (PhD). University of Pennsylvania.

- Choi, Jiyoun; Kim, Sahyang; Cho, Taehong (22 October 2020). "An apparent-time study of an ongoing sound change in Seoul Korean: A prosodic account". PLOS ONE. 15 (10): e0240682. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1540682C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240682. PMC 7580931. PMID 33091043.

- 정(Jeong), 상도(Sangdo) (31 March 2017). "도청도설 부추와 정구지" (in Korean). Kookje Newspaper.

- "Korean is virtually two languages, and that's a big problem for North Korean defectors". Public Radio International. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- "Korean Language". Asia Society. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Han, JiEun (18 March 2015). "한국어 방언 제대로 알기_'한국어 대방언과 일반론" (in Korean). [Dokseo Newspaper].

- 정(Jeong), 아란(Aran) (12 May 2020). "북한, 사투리·외래어·한자어 배격…"고유한 평양말 쓰자"" (in Korean). Yonhap News Agency.

- 이(Lee), 기갑(Kikab). "표준어와 방언의 오늘과 내일" (in Korean).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Lee, Iksop; Ramsey, S. Robert (1 January 2000). The Korean Language. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4832-8.

- "'서울 사투리?' 방송 인터뷰 모음.zip" ['Seoul dialect?' Collection of interviews.zip]. YouTube (in Korean). Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- "90년대 말투는 서울 사투리가 아니다?...서울 사투리 특징 3가지" [The way people talk in the 90s is not a Seoul dialect?...Three characteristics of Seoul dialect]. YouTube (in Korean). Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- "수원 사투리 쓰는 이창섭" [Lee Chang-seop speaks Suwon dialect.]. YouTube (in Korean). Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- Cho & Whitman (2020).

- Kanno, Hiroomi; Society for Korean Linguistics in Japan, eds. (1987). 『朝鮮語を学ぼう』 [Chōsengo o manabō] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Sanshūsha. ISBN 4-384-01506-2.

- Sohn (2006), p. 38

- Choe, Sang-hun (30 August 2006). "Koreas: Divided by a common language". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- "Beliefs that bind". Korea JoongAng Daily. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Sohn (2001), p. 6.

- "누리-세종학당".

- "TOPIK | iSeodang Korean Language Center". Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- Raugh, Harold E. "The Origins of the Transformation of the Defense Language Program" (PDF). Applied Language Learning. 16 (2): 1–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- "DLI's language guidelines". AUSA. 1 August 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- "Languages". United States Department of State. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Lee, Saekyun H.; HyunJoo Han. "Issues of Validity of SAT Subject Test Korea with Listening" (PDF). Applied Language Learning. 17 (1): 33–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008.

- "Global popularity of Korean language surges". The Korea Herald. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Pickles, Matt (11 July 2018). "K-pop drives boom in Korean language lessons". BBC News. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- "Korea Marks 558th Hangul Day". The Chosun Ilbo. 10 October 2004. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- "Korean language test-takers pass 1 mil". The Korea Times. 20 January 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "TOPIK 한국어능력시험". topik.go.kr (in Korean). Retrieved 24 October 2017.

Further reading

- Argüelles, Alexander; Kim, Jong-Rok (2000). A Historical, Literary and Cultural Approach to the Korean Language. Seoul, South Korea: Hollym.

- Argüelles, Alexander; Kim, Jongrok (2004). A Handbook of Korean Verbal Conjugation. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press.

- Argüelles, Alexander (2007). Korean Newspaper Reader. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press.

- Argüelles, Alexander (2010). North Korean Reader. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press.

- Brown, L. (2015). "Expressive, Social and Gendered Meanings of Korean Honorifics". Korean Linguistics. 17 (2): 242–266. doi:10.1075/kl.17.2.04bro.

- Chang, Suk-jin (1996). Korean. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-55619-728-4. (Volume 4 of the London Oriental and African Language Library).

- Cho, Young A. (2006). "Gender Differences in Korean Speech". In Sohn, Ho-min (ed.). Korean Language in Culture and Society. University of Hawaii Press. p. 189.

- Cho, Sungdai; Whitman, John (2020). Korean: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51485-9.

- Hulbert, Homer B. (1905). A Comparative Grammar of the Korean Language and the Dravidian Dialects in India. Seoul.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66189-8.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1966). "Lexical Evidence Relating Japanese to Korean". Language. 42 (2): 185–251. doi:10.2307/411687. JSTOR 411687.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1990). "Morphological clues to the relationship of Japanese and Korean". In Baldi, Philip (ed.). Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology. Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs. Vol. 45. pp. 483–509.

- Martin, Samuel E. (2006). A Reference Grammar of Korean: A Complete Guide to the Grammar and History of the Korean Language – 韓國語文法總監. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3771-2.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1971). Japanese and the Other Altaic Languages. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52719-0.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1996). Languages and History: Japanese, Korean and Altaic. Oslo, Norway: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture. ISBN 974-8299-69-4.

- Ramstedt, G. J. (1928). "Remarks on the Korean language". Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. 58.

- Rybatzki, Volker (2003). "Middle Mongol". In Janhunen, Juha (ed.). The Mongolic languages. London, England: Routledge. pp. 47–82. ISBN 0-7007-1133-3.

- Starostin, Sergei A.; Dybo, Anna V.; Mudrak, Oleg A. (2003). Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages. Leiden, South Holland: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13153-1. In 3 volumes.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (2001) [1999]. The Korean Language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521369435.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (2006). Korean Language in Culture and Society. Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8248-2694-9.

- Song, J.-J. (2005). The Korean Language: Structure, Use and Context. London, England: Routledge.

- Trask, R. L. (1996). Historical linguistics. Hodder Arnold.

- Vovin, Alexander (2010). Koreo-Japonica: A Re-evaluation of a Common Genetic Origin. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Whitman, John B. (1985). The Phonological Basis for the Comparison of Japanese and Korean (PhD thesis). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Unpublished Harvard University PhD dissertation.

- Yeon, Jaehoon; Brown, Lucien (2011). Korean: A Comprehensive Grammar. London, England: Routledge.

External links

- Linguistic and Philosophical Origins of the Korean Alphabet (Hangul)

- Sogang University free online Korean language and culture course

- Beginner's guide to Korean for English speakers

- U.S. Foreign Service Institute Korean basic course

- asianreadings.com, Korean readings with hover prompts

- Linguistic map of Korea

- dongsa.net, Korean verb conjugation tool

- Hanja Explorer, a tool to visualize and study Korean vocabulary

- Korean language at Curlie