History of Korea

The Lower Paleolithic era in the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria began roughly half a million years ago.[1][2][3] The earliest known Korean pottery dates to around 8000 BC, and the Neolithic period began after 6000 BC, followed by the Bronze Age by 2000 BC,[4][5][6] and the Iron Age around 700 BC.

| History of Korea |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Korea |

|---|

| History |

Similarly, according to The History of Korea, supervised by Kim Yang-ki and edited by Kang Deoksang, Jung Sanae, and Nakayama Kiyotaka, the Paleolithic people are not the direct ancestors of the present Korean (Chosun) people, but their direct ancestors are estimated to be the Neolithic People of about 2000 BC.[7]

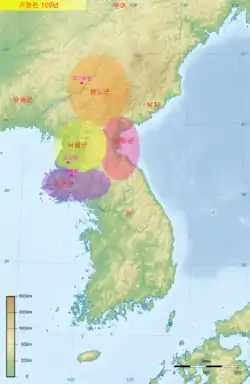

According to the mythic account recounted in the Samguk Yusa (1280s), the Gojoseon (Old Joseon) kingdom was founded in northern Korea and southern Manchuria in 2333 BC.[8][9][10] In the 12th century BC Gija, a prince from the Shang dynasty of China, purportedly founded Gija Joseon.[11][12] The first written historical record on Gojoseon can be found from the early 7th century BC.[14] The Jin state was formed in southern Korea by the 3rd century BC. In the 2nd century BC, Gija Joseon was replaced by Wiman Joseon, which fell to the Han dynasty of China near the end of the century. This resulted in the fall of Gojoseon and led to succeeding warring states, the Proto–Three Kingdoms period that spanned the later Iron Age.

From the 1st century, Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla grew to control the peninsula and Manchuria as the Three Kingdoms of Korea (57 BC–668 AD), until unification by Silla in 676. In 698, King Go established the Balhae in old territories of Goguryeo,[15][16] which led to the Northern and Southern States period (698–926) of Balhae and Silla coexisting.

In the late 9th century, Silla was divided into the Later Three Kingdoms (892–936), which ended with the unification by Wang Geon's Goryeo dynasty. Meanwhile, Balhae fell after invasions by the Khitan-led Liao dynasty and the refugees including the last crown prince emigrated to Goryeo, where the crown prince was warmly welcomed and included into the ruling family by Wang Geon, thus unifying the two successor states of Goguryeo.[17][18] During the Goryeo period, laws were codified, a civil service system was introduced, and culture influenced by Buddhism flourished. However, Mongol invasions in the 13th century brought Goryeo under the influence of the Mongol Empire and the Yuan dynasty until the mid-14th century.[19][20]

In 1392, General Yi Seong-gye established the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897) after a coup d'état that overthrew the Goryeo dynasty in 1388. King Sejong the Great (1418–1450) implemented numerous administrative, social, scientific, and economic reforms, established royal authority in the early years of the dynasty, and personally created Hangul, the Korean alphabet.

After enjoying a period of peace for nearly two centuries, the Joseon dynasty faced foreign invasions and internal factional strife from 1592 to 1637. Most notable of these invasions is the Japanese invasions of Korea, which marked the end of the Joseon dynasty's early period. The combined force of Ming dynasty of China and the Joseon dynasty repelled these Japanese invasions, but at a cost to the countries. Henceforth, Joseon gradually became more and more isolationist and stagnant. By the mid 19th century, with the country unwilling to modernize, and under encroachment of European powers, Joseon Korea was forced to sign unequal treaties with foreign powers. After the assassination of Empress Myeongseong in 1895, the Donghak Peasant Revolution, and the Gabo Reforms of 1894 to 1896, the Korean Empire (1897–1910) came into existence, heralding a brief but rapid period of social reform and modernization. However, in 1905, the Korean Empire signed a protectorate treaty and in 1910, Japan annexed the Korean Empire. Korea then became a Japanese colony from 1910 to 1945.

Korean resistance manifested in the widespread March 1st Movement of 1919. Thereafter the resistance movements, coordinated by the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in exile, became largely active in neighboring Manchuria, China proper, and Siberia, influenced by Korea's peaceful demonstrations. Figures from these exile organizations would become important in post-WWII Korea.

After the end of World War II in 1945, the Allies divided the country into a northern area (protected by the Soviets) and a southern area (protected primarily by the United States). In 1948, when the powers failed to agree on the formation of a single government, this partition became the modern states of North and South Korea. The peninsula was divided at the 38th Parallel: the "Republic of Korea" was created in the south, with the backing of the US and Western Europe, and the "Democratic People's Republic of Korea" in the north, with the backing of the Soviets and the communist People's Republic of China. The new premier of North Korea, Kim Il-sung, launched the Korean War in 1950 in an attempt to reunify the country under Communist rule. After immense material and human destruction, the conflict ended with a cease-fire in 1953. In 1991, both states were accepted into the United Nations. In 2018, the two nations agreed to work toward a final settlement to formally end the Korean War.

While both countries were essentially under military rule after the war, South Korea eventually liberalized. Since 1987 it has had a competitive electoral system. The South Korean economy has prospered, and the country is now considered to be fully developed, with a similar capital economic standing to Western Europe, Japan, and the United States.

North Korea has maintained totalitarian militarized rule, with a personality cult constructed around the Kim family. Economically, North Korea has remained heavily dependent on foreign aid. Following the end of the Soviet Union, that aid collapsed precipitously. The country's economic situation has been quite marginal since.

Prehistoric

Paleolithic

No fossil proven to be Homo erectus has been found in the Korean Peninsula,[21] though a candidate has been reported.[2] Tool-making artifacts from the Paleolithic period have been found in present-day North Hamgyong, South Pyongan, Gyeonggi, and north and south Chungcheong provinces,[22] which dates the Paleolithic Age to half a million years ago,[5] though it may have begun as late as 400,000 years ago[1] or as early as 600,000–700,000 years ago.[2][3]

Neolithic

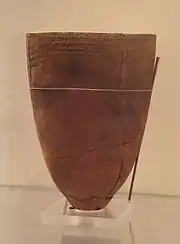

The earliest known Korean pottery dates back to around 8000 BC,[23] and evidence of Mesolithic Pit–Comb Ware culture (or Yunggimun pottery) is found throughout the peninsula, such as in Jeju Island. Jeulmun pottery, or "comb-pattern pottery", is found after 7000 BC, and is concentrated at sites in west-central regions of the Korean Peninsula, where a number of prehistoric settlements, such as Amsa-dong, existed. Jeulmun pottery bears basic design and form similarities to that of Mongolia, the Amur and Songhua river basins of Manchuria, the Jōmon culture in Japan, and the Baiyue in Southern China and Southeast Asia.[24][25]

Archaeological evidence demonstrates that agricultural societies and the earliest forms of social-political complexity emerged in the Mumun pottery period (c. 1500–300 BC).[26]

People in southern Korea adopted intensive dry-field and paddy-field agriculture with a multitude of crops in the Early Mumun Period (1500–850 BC). The first societies led by big-men or chiefs emerged in the Middle Mumun (850–550 BC), and the first ostentatious elite burials can be traced to the Late Mumun (c. 550–300 BC). Bronze production began in the Middle Mumun and became increasingly important in ceremonial and political society after 700 BC. Archeological evidence from Songguk-ri, Daepyeong, Igeum-dong, and elsewhere indicate that the Mumun era was the first in which chiefdoms rose, expanded, and collapsed. The increasing presence of long-distance trade, an increase in local conflicts, and the introduction of bronze and iron metallurgy are trends denoting the end of the Mumun around 300 BC.[26]

In addition, 73 tombs similar to the ones found in Japan, estimated to date back to Gojoseon (100 BC), have been found in the southern tip of the Korean peninsula, and the discovery of jar burials, suggest a close relationship with Japan,[27] and Gojoseon, proving that Gojoseon and Yayoi period Japan maintained close relations with one another even during the ancient times.

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is often held to have begun around 900–800 BC in Korea,[5] though the transition to the Bronze Age may have begun as far back as 2300 BC.[6] Bronze daggers, mirrors, jewelry, and weaponry have been found, as well as evidence of walled-town polities. Rice, red beans, soybeans and millet were cultivated, and rectangular pit-houses and increasingly larger dolmen burial sites are found throughout the peninsula.[28] Contemporaneous records suggest that Gojoseon transitioned from a feudal federation of walled cities into a centralised kingdom at least before the 4th-century BC.[29] It is believed that by the 4th century BC, iron culture was developing in Korea by northern influence via today's Russia's Maritime Province.[30][31]

Ancient Korea

Gojoseon

Gojoseon was the first Korean kingdom, located in the north of the peninsula and Manchuria, later alongside the state of Jin in the south of the peninsula. The historical Gojoseon kingdom was first mentioned in Chinese records in the early 7th century BC.[14] By about the 4th century BC, Gojoseon had developed to the point where its existence was well known in China,[32][33] and around this time, its capital moved to Pyongyang.[34][35]

The founding legend of Gojoseon, which is recorded in the Samguk Yusa (1281) and other medieval Korean books,[36] states that the country was established in 2333 BC by Dangun, said to be descended from heaven.[37] While no evidence has been found that supports whatever facts may lie beneath this,[38][39] the account has played an important role in developing Korean national identity.

In the 12th century BC, Gija, a prince from the Shang dynasty of China, purportedly founded Gija Joseon. In pre-modern Korea, Gija represented the authenticating presence of Chinese civilization, and until the 12th century, Koreans commonly believed that Dangun bestowed upon Korea its people and basic culture, while Gija gave Korea its high culture—and presumably, standing as a legitimate civilization.[40] However, due to contradicting historical and archaeological evidence, its existence was challenged in the 20th century, and today no longer forms the mainstream understanding of this period.

In 194 BC, Gija Joseon was overthrown by Wi Man (also known as Wei Man), a Chinese refugee from the Han vassal state of Yan. Wi Man then established Wiman Joseon.[41][42]

In 128 BC, Nan Lü (南閭), a leader of Ye who was receiving pressure from Wiman Joseon, surrendered to the Han dynasty and became the Canghai Commandery.[43][44]

Chinese commanderies

In 108 BC, the Chinese Han dynasty defeated Wiman Joseon and installed four commanderies in the northern Korean peninsula. Three of the commanderies fell or retreated westward within a few decades, but the Lelang Commandery remained as a center of cultural and economic exchange with successive Chinese dynasties for four centuries, until it was conquered by Goguryeo in 313 AD.

Jin State

Around 300 BC, a state called Jin arose in the southern part of the Korean peninsula. Very little is known about Jin, but it established relations with Han China and exported artifacts to the Yayoi of Japan.[47][48][49] Around 100 BC, Jin evolved into the Samhan confederacies.[50]

Many smaller states sprang from the former territory of Gojoseon such as Buyeo, Okjeo, Dongye, Goguryeo, and Baekje. The Three Kingdoms refer to Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla, although Buyeo and the Gaya confederacy existed into the 5th and 6th centuries respectively.

Proto–Three Kingdoms

The Proto-Three Kingdoms period, sometimes called the Several States Period (열국시대),[51] is the time before the rise of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, which included Goguryeo, Silla, and Baekje, and occurred after the fall of Gojoseon. This time period consisted of numerous states that sprang up from the former territories of Gojoseon. Among these states, the largest and most influential were Eastern Buyeo and Northern Buyeo.

Northern states

After the fall of Gojoseon, Buyeo arose in today's North Korea and southern Manchuria, from about the 2nd century BC to 494 AD. Its remnants were absorbed by Goguryeo in 494, and both Goguryeo and Baekje, two of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, considered themselves its successor.[52]

Although records are sparse and contradictory, it is thought that in 86 BC, Dongbuyeo (Eastern Buyeo) branched out, after which the original Buyeo is sometimes referred to as Bukbuyeo (Northern Buyeo). Jolbon Buyeo was the predecessor to Goguryeo, and in 538, Baekje renamed itself Nambuyeo (Southern Buyeo).[53]

Okjeo was a tribal-state that was located in the northern Korean Peninsula, and was established after the fall of Gojoseon. Okjeo had been a part of Gojoseon before its fall. It never became a fully developed kingdom due to the intervention of its neighboring kingdoms. Okjeo became a tributary of Goguryeo, and was eventually annexed into Goguryeo by Gwanggaeto the Great in the 5th century.[54]

Dongye (Eastern Ye) was another small kingdom that was situated in the northern Korean Peninsula. Dongye bordered Okjeo, and the two kingdoms faced the same fate of becoming tributaries of the growing empire of Goguryeo. Dongye was also a former part of Gojoseon before its fall.[55]

Southern states

Sam-han (삼한, 三韓) refers to the three confederacies of Mahan, Jinhan, and Byeonhan. The Samhan were located in the southern region of the Korean Peninsula.[56] The Samhan countries were strictly governed by law, with religion playing an important role. Mahan was the largest, consisting of 54 states, and assumed political, economic, and cultural dominance. Byeonhan and Jinhan both consisted of 12 states, bringing a total of 78 states within the Samhan. The Samhan were eventually conquered by Baekje, Silla, and Gaya in the 4th century.[57]

Three Kingdoms of Korea

Goguryeo

Goguryeo was founded in 37 BC by Jumong (posthumously titled as Dongmyeongseong, a royal given title).[61] Later, King Taejo centralized the government. Goguryeo was the first Korean kingdom to adopt Buddhism as the state religion in 372, in King Sosurim's reign.[62][63]

Goguryeo (also spelled as Koguryŏ) was also known as Goryeo (also spelled as Koryŏ), and it eventually became the source of the modern name of Korea.[64]

The 3rd and 4th centuries were characterized by territorial competition with the Chinese and Xianbei, resulting in both losses and gains. Goguryeo initiated the Goguryeo–Wei War by attacking a Chinese fortress in 242 in an attempt to cut off Chinese access to its territories in Korea. Cao Wei of the Three Kingdoms of China retaliated by invading and destroying Hwando in 244. This forced the king to flee with Cao Wei in pursuit and broke Goguryeo's rule over the Okjeo and Ye, damaging its economy. The king eventually settled in a new capital, and Goguryeo focused on rebuilding and regaining control. In the early 4th century Goguryeo once again attacked the Chinese (now Sima Jin) to cut off their access to Korea and this time succeeded, and soon afterward conquered Lelang and Daifang ending the Chinese presence in Korea. However Goguryeo's expansion led to confrontation with the rising Xianbeis. The Xianbeis devastated Goguryeo's capital in the mid 4th century and the king retreated. Goguryeo eventually regrouped and began striking back in the late 4th century by King Gogukyang, culminating with the conquests of Gwanggaeto the Great.[65][66]

Goguryeo reached its zenith in the 5th century, becoming a powerful empire and one of the great powers in East Asia,[67][68][69][70] when Gwanggaeto the Great and his son, Jangsu, expanded the country into almost all of Manchuria, parts of Inner Mongolia,[71] parts of Russia,[72] and took the present-day city of Seoul from Baekje.[71] Goguryeo experienced a golden age under Gwanggaeto and Jangsu,[73][74][75][76] who both subdued Baekje and Silla during their times, achieving a brief unification of the Three Kingdoms of Korea and becoming the most dominant power of the Korean peninsula.[62][71][77] Jangsu's long reign of 79 years saw the perfecting of Goguryeo's political, economic and other institutional arrangements.[78]

Goguryeo was a highly militaristic state;[79][80] in addition to contesting for control of the Korean Peninsula, Goguryeo had many military conflicts with various Chinese dynasties,[81] most notably the Goguryeo–Sui War, in which Goguryeo defeated a huge force traditionally said to number over a million men,[note 2] and contributed to the Sui dynasty's fall.[82][83][84][85][86]

In 642, the powerful general Yeon Gaesomun led a coup and gained complete control over Goguryeo. In response, Emperor Taizong of Tang China led a campaign against Goguryeo, but was defeated and retreated.[81][87][88][89] After the death of Taizong, his son Gaozong allied with the Korean kingdom of Silla and invaded Goguryeo again, but was unable to overcome Goguryeo's stalwart defenses and was defeated in 662.[90][91] However, Yeon Gaesomun died of a natural cause in 666 and Goguryeo was thrown into chaos and weakened by a succession struggle among his sons and younger brother,[92][93] with his eldest son defecting to Tang and his younger brother defecting to Silla.[94] The Tang–Silla alliance mounted a fresh invasion in 667, aided by the defector Yeon Namsaeng, and was finally able to conquer Goguryeo in 668.[95][96]

After the collapse of Goguryeo, Tang and Silla ended their alliance and fought over control of the Korean Peninsula. Silla succeeded in gaining control over most of the Korean Peninsula, while Tang gained control over Goguryeo's northern territories. However, 30 years after the fall of Goguryeo, a Goguryeo general by the name of Dae Jo-yeong founded the Korean-Mohe state of Balhae and successfully expelled the Tang presence from much of the former Goguryeo territories.

Baekje

Baekje was founded by Onjo, a Goguryeo prince and the third son of the founder of Goguryeo, in 18 BC.[97] Baekje and Goguryeo shared founding myths and originated from Buyeo.[98] The Records of the Three Kingdoms mentions Baekje as a member of the Mahan confederacy in the Han River basin (near present-day Seoul). It expanded into the southwest (Chungcheong and Jeolla provinces) of the peninsula and became a significant political and military power. In the process, Baekje came into fierce confrontation with Goguryeo and the Chinese commanderies in the vicinity of its territorial ambitions.

At its peak in the 4th century during the reign of King Geunchogo, Baekje absorbed all of the Mahan states and subjugated most of the western Korean peninsula (including the modern provinces of Gyeonggi, Chungcheong, and Jeolla, as well as part of Hwanghae and Gangwon) to a centralized government. Baekje acquired Chinese culture and technology through maritime contacts with the Southern dynasties during the expansion of its territory.[99]

Baekje was a great maritime power;[100] its nautical skill, which made it the Phoenicia of East Asia, was instrumental in the dissemination of Buddhism throughout East Asia and continental culture to Japan.[101][102] Baekje played a fundamental role in transmitting cultural developments, such as Chinese characters, Buddhism, iron-making, advanced pottery, and ceremonial burial to ancient Japan.[70][103][104][105][106][107][108] Other aspects of culture were also transmitted when the Baekje court retreated to Japan after Baekje was conquered by the Silla–Tang alliance.

Baekje was once a great military power on the Korean Peninsula, especially during the time of Geunchogo,[109] but was critically defeated by Gwanggaeto the Great and declined.[110] Ultimately, Baekje was defeated by a coalition of Silla and Tang forces in 660.[111]

Silla

According to legend, the kingdom of Silla began with the unification of six chiefdoms of the Jinhan confederacy by Park Hyeokgeose in 57 BC, in the southeastern area of Korea. Its territory included the present-day port city of Busan, and Silla later emerged as a sea power responsible for destroying Japanese pirates, especially during the Unified Silla period.[112]

Silla artifacts, including unique gold metalwork, show influence from the northern nomadic steppes and Iranian peoples and especially Persians, with less Chinese influence than are shown by Goguryeo and Baekje.[113] Silla expanded rapidly by occupying the Nakdong River basin and uniting the city-states.

By the 2nd century, Silla was a large state, occupying and influencing nearby city-states. Silla gained further power when it annexed the Gaya confederacy in 562. Silla often faced pressure from Goguryeo, Baekje and Japan, and at various times allied and warred with Baekje and Goguryeo.

Silla was the smallest and weakest of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, but it used cunning diplomatic means to make opportunistic pacts and alliances with the more powerful Korean kingdoms, and eventually Tang China, to its great advantage.[114][115]

In 660, King Muyeol of Silla ordered his armies to attack Baekje. General Kim Yu-shin, aided by Tang forces, conquered Baekje. In 661, Silla and Tang moved on Goguryeo but were repelled. King Munmu, son of Muyeol and nephew of Kim, launched another campaign in 667 and Goguryeo fell in the following year.[116]

Gaya

Gaya was a confederacy of small kingdoms in the Nakdong River valley of southern Korea since AD 42, growing out of the Byeonhan confederacy of the Samhan period. Gaya's plains were rich in iron, so export of iron tools was possible and agriculture flourished. In the early centuries, the Confederacy was led by Geumgwan Gaya in the Gimhae region. However, its leading power changed to Daegaya in the Goryeong region after the 5th century.

Constantly engaged in war with the three kingdoms surrounding it, Gaya was not developed to form a unified state, and was ultimately absorbed into Silla in 562.[117]

North and South States

The term North-South States refers to Unified Silla and Balhae, during the time when Silla controlled the majority of the Korean peninsula while Balhae expanded into Manchuria. During this time, culture and technology significantly advanced, especially in Unified Silla.

Unified Silla

After the unification wars, the Tang dynasty established outposts in the former Goguryeo, and began to establish and administer communities in Baekje. Silla attacked Tang forces in Baekje and northern Korea in 671. Tang then invaded Silla in 674 but Silla drove the Tang forces out of the peninsula by 676 to achieve unification of most of the Korean peninsula.[118]

Unified Silla was a golden age of art and culture.[119][120][121][122] During this period, long-distance trade between Unified Silla and the Abbasid Caliphate was documented by Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh in the Book of Roads and Kingdoms.[123] Buddhist monasteries such as the World Heritage Sites Bulguksa Temple and Seokguram Grotto are examples of advanced Korean architecture and Buddhist influence.[124] Other state-sponsored art and architecture from this period include Hwangnyongsa Temple and Bunhwangsa Temple. Persian chronics described Silla as located at the eastern end of China and reads 'In this beautiful country Silla, there is much gold, majestetic cities and hardworking people. Their culture is comparable with Persia'.[125]

Unified Silla carried on the maritime prowess of Baekje, which acted like the Phoenicia of medieval East Asia,[126] and during the 8th and 9th centuries dominated the seas of East Asia and the trade between China, Korea and Japan, most notably during the time of Jang Bogo; in addition, Silla people made overseas communities in China on the Shandong Peninsula and the mouth of the Yangtze River.[127][128][129][130] Unified Silla was a prosperous and wealthy country,[131] and its metropolitan capital of Gyeongju[132] was the fourth largest city in the world.[133][134][135][136]

Buddhism flourished during this time, and many Korean Buddhists gained great fame among Chinese Buddhists[137] and contributed to Chinese Buddhism,[138] including: Woncheuk, Wonhyo, Uisang, Musang,[139][140][141][142] and Kim Gyo-gak, a Silla prince whose influence made Mount Jiuhua one of the Four Sacred Mountains of Chinese Buddhism.[143][144][145][146][147]

Silla began to experience political troubles in late 8th century. This severely weakened Silla and soon thereafter, descendants of the former Baekje established Later Baekje. In the north, rebels revived Goguryeo, beginning the Later Three Kingdoms period.

Unified Silla lasted for 267 years until King Gyeongsun surrendered the country to Goryeo in 935, after 992 years and 56 monarchs.[148]

Balhae

Balhae was founded only thirty years after Goguryeo had fallen, in 698. It was founded in the northern part of former lands of Goguryeo by Dae Jo-yeong, a former Goguryeo general[149][150] or chief of Sumo Mohe.[151][152][153] Balhae controlled the northern areas of the Korean Peninsula, much of Manchuria (though it didn't occupy Liaodong Peninsula for much of history), and expanded into present-day Russian Primorsky Krai. It also adopted the culture of Tang dynasty, such as the government structure and geopolitical system.[154]

In a time of relative peace and stability in the region, Balhae flourished, especially during the reigns of King Mun and King Seon. Balhae was called the "Prosperous Country in the East".[155] However, Balhae was severely weakened and eventually conquered by the Khitan-led Liao dynasty in 926.[154] Large numbers of refugees, including Dae Gwang-hyeon, the last crown prince of Balhae, were welcomed by Goryeo.[17][156] Dae Gwang-hyeon was included in the imperial family of Wang Geon, bringing a national unification between the two successor nations of Goguryeo.[18]

No historical records from Balhae have survived, and the Liao left no histories of Balhae. While Goryeo absorbed some Balhae territory and received Balhae refugees, it compiled no known histories of Balhae either. The Samguk Sagi ("History of the Three Kingdoms"), for instance, includes passages on Balhae, but does not include a dynastic history of Balhae. The 18th century Joseon dynasty historian Yu Deuk-gong advocated the proper study of Balhae as part of Korean history, and coined the term "North and South States Period" to refer to this era.[154]

Later Three Kingdoms

The Later Three Kingdoms period (892–936) consisted of Unified Silla and the revival of Baekje and Goguryeo, known historiographically as "Later Baekje" and "Later Goguryeo". During the late 9th century, as Silla declined in power and exorbitant taxes were imposed on the people, rebellions erupted nationwide and powerful regional lords rose up against the waning kingdom.[157]

Later Baekje was founded by the general Gyeon Hwon in 892, and its capital was established in Wansanju (modern Jeonju). The kingdom was based in the southwestern regions in the former territories of Baekje. In 927, Later Baekje attacked Gyeongju, the capital of Unified Silla, and placed a puppet on the throne. Eventually, Gyeon Hwon was ousted by his sons due to a succession dispute and escaped to Goryeo, where he served as a general in the conquest of the kingdom he personally founded.[158]

Later Goguryeo was founded by the Buddhist monk Gung Ye in 901, and its original capital was established in Songak (modern Kaesong). The kingdom was based in the northern regions, which were the strongholds of Goguryeo refugees.[159][160] Later Goguryeo's name was changed to Majin in 904, and Taebong in 911. In 918, Wang Geon, a prominent general of Goguryeo descent, deposed the increasingly despotic and paranoid Gung Ye, and established Goryeo. By 936, Goryeo conquered its rivals and achieved the unification of the Later Three Kingdoms.[161]

Goryeo dynasty

Goryeo was founded by Wang Geon in 918 and became the ruling dynasty of Korea by 936. It was named "Goryeo" because Wang Geon, a descendant of Goguryeo nobility,[162] deemed the nation as the successor of Goguryeo.[156][163][164][165][166][167] Wang Geon made his hometown Kaesong (in present-day North Korea) the capital. The dynasty lasted until 1392, although the government was controlled by military regime leaders between 1170 and 1270. Goryeo (also spelled as Koryŏ) is the source of the English name "Korea".[168][169]

During this period, laws were codified and a civil service system was introduced. Buddhism flourished and spread throughout the peninsula. The development of celadon pottery flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries.[170][171] The production of the Tripitaka Koreana onto 81,258 wooden printing blocks,[172] and the invention of the metal movable type attest to Goryeo's cultural achievements.[173][174][175][176][177]

In 1018, the Liao dynasty, which was the most powerful empire of its time,[178][179] invaded Goryeo but was defeated by General Gang Gam-chan at the Battle of Kuju to end the Goryeo–Khitan War. After defeating the Khitan Empire, Goryeo experienced a golden age that lasted a century, during which the Tripitaka Koreana was completed, and there were great developments in printing and publishing, promoting learning and dispersing knowledge on philosophy, literature, religion, and science; by 1100, there were 12 universities that produced famous scholars and scientists.[180][181]

In 1231, the Mongols began their invasions of Korea during seven major campaigns and 39 years of struggle, but were unable to conquer Korea.[182] Exhausted after decades of fighting, Goryeo sent its crown prince to the Dadu to swear allegiance to the Yuan dynasty; Kublai Khan accepted, and married one of his daughters to the Korean crown prince,[182] and for the following 80 years Goryeo existed under the overlordship of the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty in China.[183][184] The two nations became intertwined for 80 years as all subsequent Korean kings married Mongol princesses,[182] and the last empress of the Yuan dynasty was a Korean woman.[185]

In the 1350s, the Yuan dynasty declined rapidly due to internal struggles, enabling King Gongmin to reform the Goryeo government.[186] Gongmin had various problems that needed to be dealt with, including the removal of pro-Yuan aristocrats and military officials, the question of land holding, and quelling the growing animosity between the Buddhists and Confucian scholars.[187] During this tumultuous period, Goryeo momentarily conquered Liaoyang in 1356, repulsed two large invasions by the Red Turbans in 1359 and 1360, and defeated the final attempt by the Yuan to dominate Goryeo when General Choe Yeong defeated an invading Yuan tumen in 1364. During the 1380s, Goryeo turned its attention to the Wokou menace and used naval artillery created by Choe Mu-seon to annihilate hundreds of pirate ships.

The Goryeo dynasty would last until 1392. Yi Seong-gye, the founder of the Joseon dynasty, took power in a coup in 1388 and after serving as the power behind the throne for two monarchs, established the Joseon dynasty in 1392.[188]

Joseon dynasty

Political history

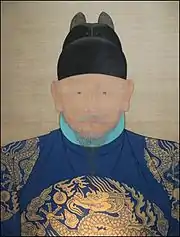

In 1392, the general Lee Seong-gye, later known as Taejo, established the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897), named in honor of the ancient kingdom Gojoseon,[189][note 3] and based on idealistic Confucianism-based ideology.[190] The prevailing philosophy throughout the Joseon dynasty was Neo-Confucianism, which was epitomized by the seonbi class, scholars who passed up positions of wealth and power to lead lives of study and integrity.

Taejo moved the capital to Hanyang (modern-day Seoul) and built Gyeongbok Palace. In 1394 he adopted Neo-Confucianism as the country's official religion, and pursued the creation of a strong bureaucratic state. His son and grandson, King Taejong and Sejong the Great, implemented numerous administrative, social, and economic reforms and established royal authority in the early years of the dynasty.[191]

During the 15th and 16th centuries, Joseon enjoyed many benevolent rulers who promoted education and science.[192] Most notable among them was Sejong the Great (r. 1418–50), who personally created and promulgated Hangul, the Korean alphabet.[193] This golden age[192] saw great cultural and scientific advancements,[194] including in printing, meteorological observation, astronomy, calendar science, ceramics, military technology, geography, cartography, medicine, and agricultural technology, some of which were unrivaled elsewhere.[195]

Internal conflicts within the royal court, civil unrest and other political struggles plagued the nation in the years that followed, worsened by the Japanese invasion of Korea between 1592 and 1598. Toyotomi Hideyoshi marshalled his forces and tried to invade the Asian continent through Korea, but was eventually repelled by the Korean military, with the assistance of the righteous armies and Chinese Ming dynasty. This war also saw the rise of the career of Admiral Lee Sun-sin with the turtle ship. As Korea was rebuilding, it had to repel invasions by the Manchu in 1627 and 1636. Internal politics were bitterly divided and settled by violence.[196] Historian JaHyun Kim Haboush, in the summary by her editor William Haboush in 2016, interpreted the decisive impact of the victories against the Japanese and Manchu invaders:

- Out of this great war at the end of the 16th century and the Manchu invasions of 1627 and 1636–1637, Koreans emerged with a discernible sense of themselves as a disethnic united by birth, language, and belief forged by this immense clash of the three great powers of East Asia ... Korea arrived at the brink of the seventeenth century as a nation.[197]

After the second Manchu invasion and stabilized relations with the new Qing dynasty, Joseon experienced a nearly 200-year period of external peace. However internally, the bitter and violent factional battles raged on. In the 18th century, King Yeongjo (r. 1724–76) and his grandson King Jeongjo (r. 1776–1800) led a new renaissance.[198] Yeongjo and Jeongjo reformed the tax system which grew the revenue stream into the treasury, strengthened the military and sponsored a revival of learning. The printing press was rejuvenated by using movable metal type; the number and quality of publications sharply increased. Jeongjo sponsored scholars from various factions to work in the Kyujanggak, or Inner Royal Library, established in 1776.[199]

19th century

Corruption in government and social unrest prevailed after 1776. The government attempted sweeping reforms in the late 19th century, but adhered to a strict isolationist policy, earning Korea the nickname "Hermit Kingdom". The policy had been established primarily for protection against Western imperialism, but soon the Joseon dynasty was forced to open trade, beginning an era leading into Japanese rule.[200]

The destabilization of the Korean nation may be said to have begun in the period of Sedo Jeongchi (Korean: 세도정치; Hanja: 勢道政治; lit. in-law politics) whereby, on the death of King Jeongjo of Joseon (r. 1776–1800), the 10-year-old Sunjo of Joseon (r. 1800–34) ascended the Korean throne, with the true power of the administration residing with his regent, Kim Jo-sun, as a representative of the Andong Kim clan. As a result, the disarray and blatant corruption in the Korean government, particularly in the three main areas of revenues – land tax, military service, and the state granary system – heaped additional hardship on the peasantry. Of special note is the corruption of the local functionaries (Hyangni), who could purchase an appointment as an administrator and so cloak their predations on the farmers with an aura of officialdom. Yangban families, formerly well-respected for their status as a noble class and being powerful both "socially and politically", were increasingly seen as little more than commoners unwilling to meet their responsibilities to their communities. Faced with increasing corruption in the government, brigandage of the disenfranchised (such as the mounted fire brigands, or Hwajok, and the boat-borne water brigands or Sujok) and exploited by the elite, many poor village folk sought to pool their resources, such as land, tools, and production, to survive. Despite the government effort in bringing an end to the practice of owning slaves in 1801, slavery in Korea remained legal until 1894.[201]

At this time, Catholic and Protestant missions were well tolerated among the nobles, most notably in and around the area of Seoul.[202] Animus and persecution by more conservative elements, the Pungyang Jo clan, took the lives of priests and followers, known as the Korean Martyrs, dissuading membership by the upper class. The peasants continued to be drawn to Christian egalitarianism, though mainly in urban and suburban areas. Arguably of greater influence were the religious teachings of Choe Je-u, (최제우, 崔濟愚, 1824–64) called "Donghak", which literally means Eastern Learning, and the religion became especially popular in rural areas. Themes of exclusionism (from foreign influences), nationalism, salvation and social consciousness were set to music, allowing illiterate farmers to understand and accept them more readily. Along with many other Koreans, Choe was alarmed by the intrusion of Christianity and the Anglo-French occupation of Beijing during the Second Opium War. He believed the best way to counter foreign influence in Korea was to introduce democratic and human rights reforms internally. Nationalism and social reform struck a chord among peasant guerrillas, and Donghak spread all across Korea. Progressive revolutionaries organized the peasants into a cohesive structure. Arrested in 1863 following the Jinju uprising led by Yu Kye-chun, Choe was charged with "misleading the people and sowing discord in society". Choe was executed in 1864, sending many of his followers into hiding in the mountains.[203]

Gojong of Korea (r. 1864–1907), enthroned at the age of 12, succeeded Cheoljong of Joseon (r. 1849–63). King Gojong's father, Heungseon Daewongun (Yi Ha-ung; 1820–98), ruled as the de facto regent and inaugurated far-ranging reforms to strengthen the central administration. Of special note was the decision to rebuild palace buildings and finance the project through additional levies on the population. Further inherited rule by a few elite ruling families was challenged by the adoption of a merit system for official appointments. In addition, Sowon – private academies – which threatened to develop a parallel system to the corrupt government and enjoyed special privileges and large landholdings, were taxed and repressed despite bitter opposition from Confucian scholars. Lastly, a policy of steadfast isolationism was enforced to staunch the increasing intrusion of Western thought and technology. He was impeached in 1873 and forced into retirement by the supporters of Empress Myeongseong, also called "Queen Min".[204]

Culture and society

Korea's culture was based on the philosophy of Neo-Confucianism, which emphasizes morality, righteousness, and practical ethics. Wide interest in scholarly study resulted in the establishment of private academies and educational institutions. Many documents were written about history, geography, medicine, and Confucian principles. The arts flourished in painting, calligraphy, music, dance, and ceramics.[205]

The most notable cultural event of this era is the creation and promulgation of the Korean alphabet Hunmin jeongeom (later called Hangul) by Sejong the Great in 1446.[193] This period also saw various other cultural, scientific and technological advances.[206]

During Joseon dynasty, a social hierarchy system existed that greatly affected Korea's social development. The king and the royal family were atop the hereditary system, with the next tier being a class of civil or military officials and landowners known as yangban, who worked for the government and lived off the efforts of tenant farmers and slaves.

A middle class, jungin, were technical specialists such as scribes, medical officers, technicians in science-related fields, artists and musicians. Commoners, sangmin, constituted the largest class in Korea. They had obligations to pay taxes, provide labor, and serve in the military. By paying land taxes to the state, they were allowed to cultivate land and farm. The lowest class, cheonmin, included tenant farmers, slaves, entertainers, craftsmen, prostitutes, laborers, shamans, vagabonds, outcasts, and criminals. Although slave status was hereditary, they could be sold or freed at officially set prices, and the mistreatment of slaves was forbidden.[207]

This yangban focused system started to change in the late 17th century as political, economic and social changes came into place. By the 19th century, new commercial groups emerged, and the active social mobility caused the yangban class to expand, resulting in the weakening of the old class system. The Korea government ordered the freedom of government slaves in 1801. The class system of Korea was completely banned in 1894.[208]

Foreign relationships

Korea dealt with a pair of Japanese invasions from 1592 to 1598 (Imjin War or the Seven Years' War). Prior to the war, Korea sent two ambassadors to scout for signs of Japan's intentions of invading Korea. However, they came back with two different reports, and while the politicians split into sides, few proactive measures were taken.

This conflict brought prominence to Admiral Yi Sun-sin as he contributed to eventually repelling the Japanese forces with the innovative use of his turtle ship, a massive, yet swift, ramming/cannon ship fitted with iron spikes.[209][210][211] The use of the hwacha was also highly effective in repelling the Japanese invaders from the land.

Subsequently, Korea was invaded in 1627 and again in 1636 by the Manchus, who went on to conquer China and establish the Qing dynasty, after which the Joseon dynasty recognized Qing suzerainty. Though Joseon respected its traditional subservient position to China, there was persistent loyalty for the perished Ming China and disdain for the Manchus, who were regarded as barbarians.

During the 19th century, Joseon tried to control foreign influence by closing its borders to all nations but China. In 1853 the USS South America, an American gunboat, visited Busan for 10 days and had amiable contact with local officials. Several Americans shipwrecked on Korea in 1855 and 1865 were also treated well and sent to China for repatriation. The Joseon court was aware of the foreign invasions and treaties involving Qing China, as well as the First and Second Opium Wars, and followed a cautious policy of slow exchange with the West.

In 1866, reacting to greater numbers of Korean converts to Catholicism despite several waves of persecutions, the Joseon court clamped down on them, massacring French Catholic missionaries and Korean converts alike. In response France invaded and occupied portions of Ganghwa Island. The Korean army lost heavily, but the French abandoned the island.

The General Sherman, an American-owned armed merchant marine sidewheel schooner, attempted to open Korea to trade in 1866. After an initial miscommunication, the ship sailed upriver and became stranded near Pyongyang. After being ordered to leave by the Korean officials, the American crewmen killed four Korean inhabitants, kidnapped a military officer and engaged in sporadic fighting that continued for four days. After two efforts to destroy the ship failed, she was finally set aflame by Korean fireships laden with explosives.

This incident is celebrated by the DPRK as a precursor to the later USS Pueblo incident. In response, the United States confronted Korea militarily in 1871, killing 243 Koreans in Ganghwa island before withdrawing. This incident is called the Shinmiyangyo in Korea. Five years later, the reclusive Korea signed a trade treaty with Japan, and in 1882 signed a treaty with the United States, ending centuries of isolationism.

Conflict between the conservative court and a reforming faction led to the Gapsin Coup in 1884. The reformers sought to reform Korea's institutionalized social inequality, by proclaiming social equality and the elimination of the privileges of the yangban class. The reformers were backed by Japan, and were thwarted by the arrival of Qing troops, invited by the conservative Queen Min. The Chinese troops departed but the leading general Yuan Shikai remained in Korea from 1885–1894 as Resident, directing Korean affairs.

In 1885, British Royal Navy occupied Geomun Island, and withdrew in 1887.

Korea became linked by telegraph to China in 1888 with Chinese controlled telegraphs. China permitted Korea to establish embassies with Russia (1884), Italy (1885), France (1886), the United States, and Japan. China attempted to block the exchange of embassies in Western countries, but not with Tokyo. The Qing government provided loans. China promoted its trade in an attempt to block Japanese merchants, which led to Chinese favour in Korean trade. Anti-Chinese riots broke out in 1888 and 1889 and Chinese shops were torched. Japan remained the largest foreign community and largest trading partner.[212]

A rapidly modernizing Meiji Japan successfully challenged China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), forcing it to abandon its long-standing claims to deference by Korea. Modernization began in Korea when Japan forced it to open its ports in 1876. However, the forces of modernization met strong opposition not only from the traditionalism of the ruling Korean elite but from the population at large, which supported the traditional Confucian system of government by gentlemen. Japan used modernization movements to gain more and more control over Korea.[213]

In 1895, the Japanese were involved in the murder of Empress Myeongseong,[214][215] who had sought Russian help, and the Russians were forced to retreat from Korea for the time.

Modern history

Korean Empire (1897–1910)

As a result of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki was concluded between China and Japan.[216] It stipulated the abolition of subordinate relationships Korea had with China, in which Korea was a tributary state of China since the Qing invasion of Joseon in 1636.

In 1897, Joseon was renamed the Korean Empire, and King Gojong became Emperor Gojong. The imperial government aimed to become a strong and independent nation by implementing domestic reforms, strengthening military forces, developing commerce and industry, and surveying land ownership. Organizations like the Independence Club also rallied to assert the rights of the Joseon people, but clashed with the government which proclaimed absolute monarchy and power.[217]

Russian influence was strong in the Empire until being defeated by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). Korean Empire effectively became a protectorate of Japan on 17 November 1905, the 1905 Protectorate Treaty having been promulgated without Emperor Gojong's required seal or commission.[218][219]

Following the signing of the treaty, many intellectuals and scholars set up various organizations and associations, embarking on movements for independence. In 1907, Gojong was forced to abdicate after Japan learned that he sent secret envoys to the Second Hague Conventions to protest against the protectorate treaty, leading to the accession of Gojong's son, Emperor Sunjong. In 1909, independence activist An Jung-geun assassinated Itō Hirobumi, former Resident-General of Korea, for Ito's intrusions on the Korean politics.[220][221] This prompted the Japanese to ban all political organizations and proceed with plans for annexation.

Japanese rule (1910–1945)

In 1910, the Empire of Japan effectively annexed Korea through the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty. Along with all other previously signed treaties between Korea and Japan, the annexation treaty was confirmed to be null and void in 1965. While Japan asserted that the treaty was concluded legally, Korea disputed the legality of the treaty, because the treaty was not signed by the Emperor of Korea as required and it violated the international convention on external pressures regarding treaties.[222][223] Many Koreans formed the Righteous army to fight against Japanese rule.[224]

Korea was controlled by Japan under a Governor-General of Chōsen from 1910 until Japan's unconditional surrender to the Allied Forces on 15 August 1945. De jure sovereignty was deemed to have passed from the Joseon dynasty to the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea.[220]

After the annexation, Japan set out to suppress many traditional Korean customs, including eventually even the Korean language itself.[225][224] Economic policies were implemented primarily for Japanese benefit.[226][227] European-styled transport and communication networks were constructed across the nation in order to extract resources and exploit labor. However, much of the built infrastructure was later destroyed during the devastating Korean War. The banking system was consolidated and the Korean currency abolished.

The Japanese removed the Joseon hierarchy and gave the census register to the baekjeong and nobi who were not allowed to have the census register during Joseon period,[228] The Gyeongbok Palace was mostly destroyed, and replaced with the office building of the Governor-General.[229]

After Emperor Gojong died in January 1919, with rumors of poisoning, independence rallies against the Japanese colonizers took place nationwide on 1 March 1919 (the March 1st Movement). This movement was suppressed by force and about 7,000 persons were killed by Japanese soldiers[note 4][230] and police.[231] An estimated 2 million people took part in peaceful, pro-liberation rallies, although Japanese records claim participation of less than half million.[232] This movement was partly inspired by United States President Woodrow Wilson's speech of 1919, declaring support for right of self-determination and an end to colonial rule after World War I.[232]

The Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was established in Shanghai, China, in the aftermath of the March 1 Movement, which coordinated the liberation effort and resistance against Japanese rule. Some of the achievements of the Provisional Government included the Battle of Chingshanli of 1920 and the ambush of Japanese military leadership in China in 1932. The Provisional Government is considered to be the de jure government of the Korean people between 1919 and 1948. The legitimacy of the provisional government is enshrined into the preamble of the constitution of the Republic of Korea.[233]

So far as primary and secondary education in Korea were classified as being for “those habitually using the Korean language”, and for “those habitually using the Japanese language”. Thus, the ethnic Koreans could attend the schools primarily for Japanese, and vice versa.[234]

As of 1926, the Korean language was taught for 4 hours a week for the first and second year of a common school having a six-year course, 3 for the rest of the course. Both Japanese and Koreans paid school-fees, without exception. The average fee in a common school was about 25 cents a month. The educational assessment levied by District educational bodies, paid by the ethnic Koreans, averaged about 20 cents in 1923, per capita of the Korean population, that levied by school associations, paid by the ethnic Japanese, averaged about 3.30 dollars per capita of the Japanese population comprised within all the school associations in Korea.[235]

The literacy rate of Korea reached 22% in 1945.[236] The school curriculum was radically modified to eliminate teaching of the Korean language and history.[220] The Korean language was banned, and Koreans were forced to adopt Japanese names,[237][note 5][238] and newspapers were prohibited from publishing in Korean. Numerous Korean cultural artifacts were destroyed or taken to Japan.[239] According to an investigation by the South Korean government, 75,311 cultural assets were taken from Korea.[239][240]

Some Koreans left the Korean Peninsula for exile in China, the United States, and elsewhere. Koreans in Manchuria formed resistance groups known as Dongnipgun (Liberation Army); they would travel in and out of the Sino-Korean border, fighting guerrilla warfare with Japanese forces. Some of them would group together in the 1940s as the Korean Liberation Army, which took part in allied action in China and parts of South East Asia. Tens of thousands of Koreans also joined the People's Liberation Army and the National Revolutionary Army.

The expulsion of the Japanese in 1945 removed practically all administrative and technical expertise. While the Japanese only comprised 2.6 percent of the population in 1944, they were an urban elite. The largest 50 cities contained 71 percent of the Japanese but only 12 percent of the Koreans. They largely dominated the ranks of the well-educated occupations. Meanwhile, 71 percent of the Koreans worked on farms.[241]

Division and Korean War (1945–1953)

At the Cairo Conference on November 22, 1943, the US, UK, and China agreed that "in due course Korea shall become free and independent";[242][243] at a later meeting in Yalta in February 1945, the Allies agreed to establish a four-power trusteeship over Korea.[244] On August 14, 1945, Soviet forces entered Korea by amphibious landings, enabling them to secure control in the north. Japan surrendered to the Allied Forces on August 15, 1945.

The unconditional surrender of Japan, combined with fundamental shifts in global politics and ideology, led to the division of Korea into two occupation zones, effectively starting on September 8, 1945. The United States administered the southern half of the peninsula and the Soviet Union took over the area north of the 38th parallel. The Provisional Government was ignored, mainly due to American belief that it was too aligned with the communists.[245] This division was meant to be temporary and was intended to return a unified Korea back to its people after the United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Republic of China could arrange a single government.

In December 1945, a conference convened in Moscow to discuss the future of Korea.[246] A 5-year trusteeship was discussed, and a joint Soviet-American commission was established. The commission met intermittently in Seoul but members deadlocked over the issue of establishing a national government. In September 1947, with no solution in sight, the United States submitted the Korean question to the United Nations General Assembly. On December 12, 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations recognised the Republic of Korea as the sole legal government of Korea.[247]

On June 25, 1950, the Korean War broke out when North Korea breached the 38th parallel line to invade the South, ending any hope of a peaceful reunification for the time being. After the war, the 1954 Geneva conference failed to adopt a solution for a unified Korea. Approximately 3 million people died in the Korean War, with a higher proportional civilian death toll than World War II or the Vietnam War, making it perhaps the deadliest conflict of the Cold War-era. In addition, virtually all of Korea's major cities were destroyed by the war.[248][249][250][251][252]

Modern Korea (1953–present)

Beginning with Syngman Rhee in 1948, a series of autocratic governments took power in South Korea with American support and influence.

With the coup of Park Chung-hee in 1961, a new economic policy began. In order to promote economic development, a policy of export-oriented industrialization was applied. President Park developed the South Korean economy through a series of highly successful Five-Year Plans. South Korea's economic development was spearheaded by the chaebol, family conglomerates such as Samsung, Hyundai, SK Group and LG Corporation. The chaebol received state-backing via tax breaks and cheap loans, and took advantage of South Korea's inexpensive labor to produce exportable products.[253] The government made education a very high priority to create a well-educated populace capable of productively contributing to the economy. Despite occasional political instability, the Korean economy subsequently saw enormous growth for nearly forty years, in a period known as the Miracle on the Han River. The unparalleled economic miracle brought South Korea from one of the poorest states in the world after the Korean War into a fully developed country within a generation.

South Korea eventually transitioned into a market-oriented democracy in 1987 largely due to popular demand for political reform, and then hosted the 1988 Summer Olympics, the second Summer Olympic Games to be held on the Asian continent, in the following year.

Moving on from cheap, lower-value light industry exports, the South Korean economy eventually moved onto more capital-intensive, higher-value industries, such as information technology, shipbuilding, auto manufacturing, and petroleum refining. Today, South Korea is a leading economy and a technological powerhouse, rivaling even countries such as the United States in information and communications technology. South Korean pop culture has also boomed abroad in recent years, in a phenomenon known as the Korean Wave.

Due to Soviet Influence, North Korea established a communist government with a hereditary succession of leadership, with ties to China and the Soviet Union. Kim Il-sung became the supreme leader until his death in 1994, after which his son, Kim Jong-il took power. Kim Jong-il's son, Kim Jong-un, is the current leader, taking power after his father's death in 2011. After the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, the North Korean economy went on a path of steep decline, and it is currently heavily reliant on international food aid and trade with China.

See also

- Korean monarchs' family trees: Silla; Goryeo; Joseon

- Korean nationalist historiography

- Korean influence on Japanese culture

- List of monarchs of Korea

- Military history of Korea

- National Treasure of South Korea

- Prehistoric Korea

- South Korea–United States relations

- Timeline of Korean history

References

- Eckert & Lee 1990, p. 2

- Christopher J. Norton, "The Current State of Korean Paleoanthropology", (2000), Journal of Human Evolution, 38: 803–825.

- Sin 2005, p. 17

- Eckert & Lee 1990, p. 9

- Connor 2002, p. 9

- Jong Chan Kim, Christopher J Bae, "Radiocarbon Dates Documenting The Neolithic-Bronze Age Transition in Korea" Archived 2012-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, (2010), Radiocarbon, 52: 2, pp. 483–492.

- 金両基監修『韓国の歴史』河出書房新社 2002、p.2

- Sin 2005, p. 19.

- Lee, Ki-baik 1984, pp. 14, 167.

- Seth 2010, p. 17.

- Kim, Djun Kil 2014, p. 8.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne (2013). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-133-60651-2.

- Peterson & Margulies 2009, p. 6.

- Pratt 2007, p. 63-64.

- Peterson & Margulies 2009, p. 35-36.

- Kim Jongseo, Jeong Inji, et al. "Goryeosa (The History of Goryeo)", 1451, Article for July 934, 17th year in the Reign of Taejo

- Lee, Ki-baik 1984, p. 103, "When Parhae perished at the hands of the Khitan around this same time, much of its ruling class, who were of Koguryŏ descent, fled to Koryŏ. Wang Kŏn warmly welcomed them and generously gave them land. Along with bestowing the name Wang Kye ("Successor of the Royal Wang") on the Parhae crown prince, Tae Kwang-hyŏn, Wang Kŏn entered his name in the royal household register, thus clearly conveying the idea that they belonged to the same lineage, and also had rituals performed in honor of his progenitor. Thus Koryŏ achieved a true national unification that embraced not only the Later Three Kingdoms but even survivors of Koguryŏ lineage from the Parhae kingdom."

- Seth 2011, p. 112.

- Kim, Djun Kil 2014, pp. 65–68.

- Early Human Evolution: Homo ergaster and erectus Archived 2007-12-19 at the Wayback Machine. Anthro.palomar.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 8–12.

- Chong Pil Choe, Martin T. Bale, "Current Perspectives on Settlement, Subsistence, and Cultivation in Prehistoric Korea", (2002), Arctic Anthropology, 39: 1–2, pp. 95–121.

- Stark 2005, p. 137.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 23–26.

- Nelson 1993, pp. 110–116.

- 小片丘彦「朝鮮半島出土古人骨の時代的特徴」『鹿児島大学歯学部紀要』 (18), 1–8, 1998

- Gochang, Hwasun and Ganghwa Dolmen Sites Archived 2017-02-18 at the Wayback Machine, UNESCO

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 82–85.

- "Large-scale 2nd to 3rd century AD bloomery iron smelting in Korea".

- Wontack Hong, "The Yemaek Tungus of Central Manchuria and Korean Peninsula: Interactions between the Xianbei and the Yemaek Tungus"

- Eckert & Lee 1990, p. 11.

- Lee, Ki-baik 1984, p. 14.

- (in Korean) Gojoseon territory at Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

- Timeline of Art and History, Korea, 1000 BC-1 AD Archived 2010-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- See also Jewang Ungi (1287) and Dongguk Tonggam (1485).

- Hwang 2010, p. 2.

- Connor 2002, p. 10.

-

- Seth 2010, p. 443: "An extreme manifestation of nationalism and the family cult was the revival of interest in Tangun, the mythical founder of the first Korean state... Most textbooks and professional historians, however, treat him as a myth."

- Stark 2008, p. 49: "Although Kija may have truly existed as a historical figure, Tangun is more problematical."

- Schmid 2013, p. 270: "Most [Korean historians] treat the [Tangun] myth as a later creation."

- Peterson & Margulies 2009, p. 5: "The Tangun myth became more popular with groups that wanted Korea to be independent; the Kija myth was more useful to those who wanted to show that Korea had a strong affinity to China."

- Hulbert 2014, p. 73: "If a choice is to be made between them, one is faced with the fact that the Tangun, with his supernatural origin, is more clearly a mythological figure than Kija."

- Kyung Moon hwang, "A History of Korea, An Episodic Narrative", 2010, p. 4

- Academy of Korean Studies, The Review of Korean Studies, vol. 10권,3–4, 2007, p. 222

- Lee Injae, Owen Miller, Park Jinhoon, Yi Hyun-Hae, Korean History in Maps, Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 20

- 창해군 한국민족문화대백과 Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

- "남려". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- "Early Korea". Archived from the original on 2015-06-25.

-

- 매국사학의 몸통들아, 공개토론장으로 나와라!. ngonews. 2015-12-24. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19.

- 요서 vs 평양… 한무제가 세운 낙랑군 위치 놓고 열띤 토론. Segye Ilbo. 2016-08-21. Archived from the original on 2017-04-13.

- "갈석산 동쪽 요서도 고조선 땅" vs "고고학 증거와 불일치". The Dong-a Ilbo. 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- Yayoi Period History Summary Archived 2008-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, BookRags.com

- Japanese Roots Archived 2012-05-25 at archive.today, Jared Diamond, Discover 19:6 (June 1998)

- The Genetic Origins of the Japanese Archived 2016-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, Thayer Watkins

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 92–95.

- (in Korean) Proto-Three Kingdoms period at Doosan Encyclopedia

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 109–116.

- (in Korean) Buyeo Archived 2012-07-01 at archive.today at Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 128–130.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 130–131.

- (in Korean) Samhan at Doosan Encyclopedia

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 135–141.

- Library, British (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- Grenet, Frantz (2004). "Maracanda/Samarkand, une métropole pré-mongole". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 5/6: Fig. C.

- (in Korean) Goguryeo at Doosan Encyclopedia

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 199–202.

- (in Korean) Buddhism in Goguryeo at Doosan Encyclopedia

- Fan Ye, Book of the Later Han, volume 85; the Dongyi Liezhuan

- Charles Roger Tennant (1996). A history of Korea. Kegan Paul International. p. 22. ISBN 0-7103-0532-X.

- Byington, Mark E. "Control or Conquer? Koguryǒ's Relations with States and Peoples in Manchuria," Journal of Northeast Asian History volume 4, number 1 (June 2007):93. pages 93–96

- Roberts, John Morris; Westad, Odd Arne (2013). The History of the World. Oxford University Press. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-19-993676-2. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Gardner, Hall (27 November 2007). Averting Global War: Regional Challenges, Overextension, and Options for American Strategy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-0-230-60873-3. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Laet, Sigfried J. de (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. p. 1133. ISBN 978-92-3-102813-7. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Walker 2012, pp. 6–7.

- Kim, Jinwung 2012, p. 35.

- Kotkin, Stephen; Wolff, David (2015-03-04). Rediscovering Russia in Asia: Siberia and the Russian Far East: Siberia and the Russian Far East. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-46129-6. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- Yi, Hyŏn-hŭi; Pak, Sŏng-su; Yun, Nae-hyŏn (2005). New history of Korea. Jimoondang. p. 201. ISBN 978-89-88095-85-0. Archived from the original on 2016-12-04.

He launched a military expedition to expand his territory, opening the golden age of Goguryeo.

- Hall, John Whitney (1988). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-521-22352-2. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Scribner. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-684-18899-7. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Cohen, Warren I. (2000-12-20). East Asia at the Center: Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. Columbia University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-231-50251-1. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "Kings and Queens of Korea". KBS World Radio. Korea Communications Commission. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Lee, Ki-baik 1984, pp. 38–40.

- Lee, Ki-baik 1984, pp. 23–24.

- Walker 2012, p. 104.

- Walker 2012, p. 161.

- White, Matthew (7 November 2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-393-08192-3. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Grant, Reg G. (2011). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of World History. Universe Pub. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-7893-2233-3. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Bedeski, Robert (12 March 2007). Human Security and the Chinese State: Historical Transformations and the Modern Quest for Sovereignty. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-134-12597-5. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- Lee, Ki-baik 1984, p. 47, "Koguryŏ was the first to open hostilities, with a bold assault across the Liao River against Liao-hsi, in 598. The Sui emperor, Wen Ti, launched a retaliatory attack on Koguryŏ but met with reverses and turned back in mid-course. Yang Ti, the next Sui emperor, proceeded in 612 to mount an invasion of unprecedented magnitude, marshalling a huge force said to number over a million men. And when his armies failed to take Liao-tung Fortress (modern Liao-yang), the anchor of Koguryŏ's first line of defense, he had a nearly a third of his forces, some 300,000 strong, break off the battle there and strike directly at the Koguryŏ capital of P'yŏngyang. But the Sui army was lured into a trap by the famed Koguryŏ commander Ŭlchi Mundŏk, and suffered a calamitous defeat at the Salsu (Ch'ŏngch'ŏn) River. It is said that only 2,700 of the 300,000 Sui soldiers who had crossed the Yalu survived to find their way back, and the Sui emperor now lifted the siege of Liao-tung Fortress and withdrew his forces to China proper. Yang Ti continued to send his armies against Koguryŏ but again without success, and before long his war-weakened empire crumbled."

- Nahm 2005, p. 18: "China, which had been split into many states since the early 3rd century, was reunified by the Sui dynasty at the end of the 6th century. Soon after that, Sui China mobilized a large number of troops and launched a sagiwar against Koguryŏ. However, the people of Koguryŏ were united and they were able to repel the Chinese aggressors. In 612, Sui troops invaded Korea again, but Koguryŏ forces fought bravely and destroyed Sui troops everywhere. General Ŭlchi Mundŏk of Koguryŏ completely wiped out some 300,000 Sui troops which came across the Yalu River in the battles near the Salsu River (now Ch'ŏngch'ŏn River) with his ingenious military tactics. Only 2,700 Sui troops were able to flee from Korea. The Sui dynasty, which wasted so much energy and manpower in aggressive wars against Koguryŏ, fell in 618."

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009-12-23). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 214–222.

- Kim, Jinwung 2012, p. 50.

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (2012-11-12). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 486. ISBN 978-1-136-63979-1. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (2014-12-15). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-107-09846-6. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- Kim, Jinwung 2012, p. 51.

- Kim, Djun Kil 2014, p. 49.

- Lee, Ki-baik 1984, p. 67.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 224–225.

- Lee, Ki-baik 1984, p. 67, "Loath to let slip such an opportunity, T'ang mounted a fresh invasion under Li Chi in 667 and Silla launched a coordinated offensive. This time the T'ang army received every possible assistance from the defector Namsaeng, and although Koguryŏ continued to hold out for another year, the end finally came in 668."

- Jonathan W. Best, A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of "The Paekche Annals" of the "Samguk sagi" (Harvard East Asian Monographs, 2007).

- The National Folk Museum of Korea (South Korea) (2014). Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Literature: Encyclopedia of Korean Folklore and Traditional Culture Vol. III. 길잡이미디어. p. 41. ISBN 978-89-289-0084-8. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 202–206.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Houghton Mifflin. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-618-13384-0. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Kitagawa, Joseph (2013-09-05). The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture. Routledge. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-136-87590-8. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2013). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-111-80815-0. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Korean Buddhism Basis of Japanese Buddhism Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Seoul Times, 2006-06-18

- Buddhist Art of Korea & Japan Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Asia Society Museum

- Kanji Archived 2012-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, JapanGuide.com

- Pottery – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. "The pottery of the Yayoi culture (300? BC-AD 250?), made by a Mongol people who came from Korea to Kyūshū, has been found throughout Japan. "

- History of Japan Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, JapanVisitor.com

- Archived 2009-10-31.

- A Brief History of Korea. Ewha Womans University Press. January 2005. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-89-7300-619-9. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Yu, Chai-Shin (2012). The New History of Korean Civilization. iUniverse. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4620-5559-3. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Baekje history Archived 2009-02-14 at the Wayback Machine, Baekje History & Culture Hall

- Lee 1997, pp. 48–49.

- Nelson 1993, pp. 243–258.

- Kim, Jinwung 2012, pp. 44–45.

- Wells, Kenneth M. (2015-07-03). Korea: Outline of a Civilisation. BRILL. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-90-04-30005-7. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 222–225.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 159–162.

- Lee, Park & Yoon 2005, pp. 241–242.

- DuBois, Jill (2004). Korea. Marshall Cavendish. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7614-1786-6. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

golden age of art and culture.

- Randel, Don Michael (28 November 2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music. Harvard University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-674-01163-2. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Hopfner, Jonathan (10 September 2013). Moon Living Abroad in South Korea. Avalon Travel. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-61238-632-4. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Kim, Djun Kil 2005, p. 47.

- Isabella Bird (9 January 2014). "1". Korea and Her Neighbours.: A Narrative of Travel, with an Account of the Recent Vicissitudes and Present Position of the Country. With a Preface by Sir Walter C. Hillier. Adegi Graphics LLC. ISBN 978-0-543-01434-4.

- Seokguram Grotto and Bulguksa Temple Archived 2016-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, UNESCO

- "Cultural ties put Iran, S Korea closer than ever for cooperation". Tehran Times. 2016-05-05. Archived from the original on 2017-04-13. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- Kitagawa, Joseph (5 September 2013). The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture. Routledge. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-136-87590-8. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

Korea held a dominant position in the north-eastern seas.

- Reischauer, Edwin Oldfather (1955). Ennins Travels in Tang China. John Wiley & Sons Canada, Limited. pp. 276–283. ISBN 978-0-471-07053-5. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

From what Ennin tells us, it seems that commerce between East China, Korea and Japan was, for the most part, in the hands of men from Silla. Here in the relatively dangerous waters on the eastern fringes of the world, they performed the same functions as did the traders of the placid Mediterranean on the western fringes. This is a historical fact of considerable significance but one which has received virtually no attention in the standard historical compilations of that period or in the modern books based on these sources. . . . While there were limits to the influence of the Koreans along the eastern coast of China, there can be no doubt of their dominance over the waters off these shores. . . . The days of Korean maritime dominance in the Far East actually were numbered, but in Ennin's time the men of Silla were still the masters of the seas in their part of the world.

- Kim, Djun Kil 2014, p. 3.

- Seth 2006, p. 65.

- MacGregor, Neil (6 October 2011). A History of the World in 100 Objects. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-196683-0. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Chŏng, Yang-mo; Smith, Judith G.; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (1998). Arts of Korea. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-87099-850-8. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- International, Rotary (February 1996). The Rotarian. Rotary International. p. 28. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Ross, Alan (17 January 2013). After Pusan. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-29935-5. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Mason, David A. "Gyeongju, Korea's treasure house". Korea.net. Korean Culture and Information Service (KOCIS). Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Adams, Edward Ben (1986). Koreaʾs pottery heritage. Seoul International Pub. House. p. 53. ISBN 9788985113069. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Mun, Chanju; Green, Ronald S. (2006). Buddhist Exploration of Peace and Justice. Blue Pine Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-9777553-0-1. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- McIntire, Suzanne; Burns, William E. (2010-06-25). Speeches in World History. Infobase Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4381-2680-7. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013-11-24). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Poceski, Mario (2007-04-13). Ordinary Mind as the Way: The Hongzhou School and the Growth of Chan Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-804320-1. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Wu, Jiang; Chia, Lucille (2015-12-15). Spreading Buddha's Word in East Asia: The Formation and Transformation of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. Columbia University Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-231-54019-3. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Wright, Dale S. (2004-03-25). The Zen Canon: Understanding the Classic Texts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988218-2. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Su-il, Jeong (2016-07-18). The Silk Road Encyclopedia. Seoul Selection. ISBN 978-1-62412-076-3. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Nikaido, Yoshihiro (2015-10-28). Asian Folk Religion and Cultural Interaction. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 137. ISBN 978-3-8470-0485-1. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- Leffman, David; Lewis, Simon; Atiyah, Jeremy (2003). China. Rough Guides. p. 519. ISBN 978-1-84353-019-0. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.