Malay language

Malay (/məˈleɪ/;[5] Malay: Bahasa Melayu, Jawi: بهاس ملايو, Rencong: ꤷꥁꤼ ꤸꥍꤾꤿꥈ) is an Austronesian language that is an official language of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, and that is also spoken in East Timor and parts of the Philippines and Thailand. Altogether, it is spoken by 290 million people[6] (around 260 million in Indonesia alone in its own literary standard named "Indonesian")[7] across Maritime Southeast Asia.

| Malay | |

|---|---|

| Bahasa Melayu بهاس ملايو ꤷꥁꤼ ꤸꥍꤾꤿꥈ | |

| Pronunciation | [ba.ha.sa mə.la.ju] |

| Native to | Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Thailand, Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands |

| Ethnicity | Malays Indonesians (see also Malayophones) |

| Speakers | L1 – 77 million (2007)[1] Total (L1 and L2): 200–290 million (2009)[2] |

Austronesian

| |

Early forms | Ancient Malay

|

Standard forms |

|

| |

Signed forms |

|

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

Recognised minority language in |

|

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ms |

| ISO 639-2 | may (B) msa (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | msa – inclusive codeIndividual codes: zlm – Malay (individual language)kxd – Brunei Malayind – Indonesianzsm – Standard Malayjax – Jambi Malaymeo – Kedah Malaykvr – Kerincixmm – Manado Malaymin – Minangkabaumui – Musizmi – Negeri Sembilanmax – North Moluccan Malaymfa – Kelantan-Pattani Malaycoa – Cocos Malaybjn – Banjaresebew – Betawimsi – Sabah Malaymqg – Kota Bangun Kutai Malay |

| Glottolog | indo1326 partial match |

| Linguasphere | 31-MFA-a |

Countries where Malay is spoken

Official language

Recognized minority or trade language | |

As the bahasa kebangsaan or bahasa nasional ("national language") of several states, Standard Malay has various official names. In Malaysia, it is designated as either Bahasa Melayu Malaysia ("Malaysian Malay") or also Bahasa Melayu ("Malay language"). In Singapore and Brunei, it is called Bahasa Melayu ("Malay language"). In Indonesia, an autonomous normative variety called Bahasa Indonesia ("Indonesian language") is designated the bahasa persatuan/pemersatu ("unifying language" or lingua franca). However, in areas of Central to Southern Sumatra, where vernacular varieties of Malay are indigenous, Indonesians refer to the language as bahasa Melayu, and consider it to be one of their regional languages.

Malay, also called Court Malay, was the literary standard of the pre-colonial Malacca and Johor Sultanates and so the language is sometimes called Malacca, Johor or Riau Malay (or various combinations of those names) to distinguish it from the various other Malayic languages. According to Ethnologue 16, several of the Malayic varieties they currently list as separate languages, including the Orang Asli varieties of Peninsular Malay, are so closely related to standard Malay that they may prove to be dialects. There are also several Malay trade and creole languages based on a lingua franca derived from Classical Malay as well as Macassar Malay, which appears to be a mixed language.

Origin

Malay historical linguists agree on the likelihood of the Malay homeland being in Northwestern Borneo.[8] A form known as Proto-Malay was spoken in Borneo at least by 1000 BCE and was, it has been argued, the ancestral language of all subsequent Malayic languages. Its ancestor, Proto-Malayo-Polynesian, a descendant of the Proto-Austronesian language, began to break up by at least 2000 BCE, possibly as a result of the southward expansion of Austronesian peoples into Maritime Southeast Asia from the island of Taiwan.[9]

History

.pdf.jpg.webp)

The history of the Malay language can be divided into five periods: Old Malay, the Transitional Period, the Classical Malay, Late Modern Malay and Modern Malay. Old Malay is believed to be the actual ancestor of Classical Malay.[10]

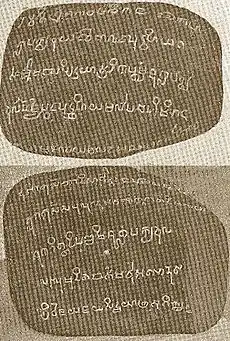

Old Malay was influenced by Sanskrit, the literary language of Classical India and a liturgical language of Hinduism and Buddhism. Sanskrit loanwords can be found in Old Malay vocabulary. The earliest known stone inscription in the Old Malay language was found in Sumatra, Indonesia, written in the Pallava variety of the Grantha alphabet[11] and is dated 1 May 683. Known as the Kedukan Bukit inscription, it was discovered by the Dutchman M. Batenburg on 29 November 1920 at Kedukan Bukit, South Sumatra, on the banks of the Tatang, a tributary of the Musi River. It is a small stone of 45 by 80 centimetres (18 by 31 in).

Other evidence is the Tanjung Tanah Law in post-Pallava letters.[12] This 14th-century pre-Islamic legal text was produced in the Adityawarman era (1345–1377) of Dharmasraya, a Hindu-Buddhist kingdom that arose after the end of Srivijayan rule in Sumatra. The laws were for the Minangkabau people, who today still live in the highlands of Sumatra, Indonesia.

Terengganu Inscription Stone (Malay: Batu Bersurat Terengganu; Jawi: باتو برسورت ترڠݢانو) is a granite stele carrying inscription in Jawi script that was found in Terengganu, Malaysia is the earliest evidence of classical Malay inscription. The inscription, dated possibly to 702 AH (corresponds to 1303 CE), constituted the earliest evidence of Jawi writing in the Malay world of Southeast Asia, and was one of the oldest testimonies to the advent of Islam as a state religion in the region. It contains the proclamation issued by a ruler of Terengganu known as Seri Paduka Tuan, urging his subjects to extend and uphold Islam and providing 10 basic Sharia laws for their guidance.

The Malay language came into widespread use as the lingua franca of the Malacca Sultanate (1402–1511). During this period, the Malay language developed rapidly under the influence of Islamic literature. The development changed the nature of the language with massive infusion of Arabic, Tamil and Sanskrit vocabularies, called Classical Malay. Under the Sultanate of Malacca the language evolved into a form recognisable to speakers of modern Malay. When the court moved to establish the Johor Sultanate, it continued using the classical language; it has become so associated with Dutch Riau and British Johor that it is often assumed that the Malay of Riau is close to the classical language. However, there is no closer connection between Malaccan Malay as used on Riau and the Riau vernacular.[13]

Among the oldest surviving letters written in Malay are the letters from Sultan Abu Hayat of Ternate, Maluku Islands in present-day Indonesia, dated around 1521–1522. The text is addressed to the king of Portugal, following contact with Portuguese explorer Francisco Serrão.[14] The letters show sign of non-native usage; the Ternateans used (and still use) the unrelated Ternate language, a West Papuan language, as their first language. Malay was used solely as a lingua franca for inter-ethnic communications.[14]

Classification

Malay is a member of the Austronesian family of languages, which includes languages from Southeast Asia and the Pacific Ocean, with a smaller number in continental Asia. Malagasy, a geographic outlier spoken in Madagascar in the Indian Ocean, is also a member of this language family. Although these languages are not necessarily mutually intelligible to any extent, their similarities are often quite apparent. In more conservative languages like Malay, many roots have come with relatively little change from their common ancestor, Proto-Austronesian language. There are many cognates found in the languages' words for kinship, health, body parts and common animals. Numbers, especially, show remarkable similarities.

Within Austronesian, Malay is part of a cluster of numerous closely related forms of speech known as the Malayic languages, which were spread across Malaya and the Indonesian archipelago by Malay traders from Sumatra. There is disagreement as to which varieties of speech popularly called "Malay" should be considered dialects of this language, and which should be classified as distinct Malay languages. The vernacular of Brunei—Brunei Malay—for example, is not readily intelligible with the standard language, and the same is true with some lects on the Malay Peninsula such as Kedah Malay. However, both Brunei and Kedah are quite close.[15]

Writing system

Malay is now written using the Latin script, known as Rumi in Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore or Latin in Indonesia, although an Arabic script called Arab Melayu or Jawi also exists. Latin script is official in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Malay uses Hindu-Arabic numerals.

Rumi (Latin) and Jawi are co-official in Brunei only. Names of institutions and organisations have to use Jawi and Rumi (Latin) scripts. Jawi is used fully in schools, especially the religious school, sekolah agama, which is compulsory during the afternoon for Muslim students aged from around 6–7 up to 12–14.

Efforts are currently being undertaken to preserve Jawi in Malaysia, and students taking Malay language examinations in Malaysia have the option of answering questions using Jawi.

The Latin script, however, is the most commonly used in Brunei and Malaysia, both for official and informal purposes.

Historically, Malay has been written using various scripts. Before the introduction of Arabic script in the Malay region, Malay was written using the Pallava, Kawi and Rencong scripts; these scripts are no longer frequently used, but similar scripts such as the Cham alphabet are used by the Chams of Vietnam and Cambodia. Old Malay was written using Pallava and Kawi script, as evident from several inscription stones in the Malay region. Starting from the era of kingdom of Pasai and throughout the golden age of the Malacca Sultanate, Jawi gradually replaced these scripts as the most commonly used script in the Malay region. Starting from the 17th century, under Dutch and British influence, Jawi was gradually replaced by the Rumi script.[16]

Extent of use

Malay is spoken in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, East Timor, Singapore and southern of Thailand.[17] Indonesia regulates its own normative variety of Malay, while Malaysia and Singapore use a common standard.[18] Brunei, in addition to Standard Malay, uses a distinct vernacular dialect called Brunei Malay. In East Timor, Indonesian is recognised by the constitution as one of two working languages (the other being English), alongside the official languages of Tetum and Portuguese.[4] The extent to which Malay is used in these countries varies depending on historical and cultural circumstances. Malay is the national language in Malaysia by Article 152 of the Constitution of Malaysia, and became the sole official language in Peninsular Malaysia in 1968 and in East Malaysia gradually from 1974. English continues, however, to be widely used in professional and commercial fields and in the superior courts. Other minority languages are also commonly used by the country's large ethnic minorities. The situation in Brunei is similar to that of Malaysia. In the Philippines, Indonesian is spoken by the overseas Indonesian community in Davao City, and functional phrases are taught to members of the Philippine Armed Forces and to students.

Phonology

Malay, like most Austronesian languages, is not a tonal language.

Consonants

The consonants of Malaysian[19][20] and also Indonesian[21] are shown below. Non-native consonants that only occur in borrowed words, principally from Arabic and English, are shown in brackets.

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar/

Alveolar |

Post‑alveolar/ Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | (q) | (ʔ) | |

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | ɡ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | (f) | (θ) | s | (ʃ) | (x) | h | |

| voiced | (v) | (ð) | (z) | (ɣ) | ||||

| Approximant | central | j | w | |||||

| lateral | l | |||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||

Orthographic note: The sounds are represented orthographically by their symbols as above, except:

- /ð/ is 'z', the same as the /z/ sound (only occurs in Arabic loanwords originally containing the /ð/ sound, but the writing is not distinguished from Arabic loanwords with /z/ sound, and this sound must be learned separately by the speakers).

- /ɲ/ is 'ny'; 'n' before 'c' and 'j'

- /ŋ/ is 'ng'

- /θ/ is represented as 's', the same as the /s/ sound (only occurs in Arabic loanwords originally containing the /θ/ sound, but the writing is not distinguished from Arabic loanwords with /s/ sound, and this sound must be learned separately by the speakers). Previously (before 1972), this sound was written 'th' in Standard Malay (not Indonesian)

- the glottal stop /ʔ/ is final 'k' or an apostrophe ' (although some words have this glottal stop in the middle, such as rakyat)

- /tʃ/ is 'c'

- /dʒ/ is 'j'

- /ʃ/ is 'sy'

- /x/ is 'kh'

- /j/ is 'y'

- /q/ is 'k'

Loans from Arabic:

- Phonemes which occur only in Arabic loans may be pronounced distinctly by speakers who know Arabic. Otherwise they tend to be replaced with native sounds.

| Distinct | Assimilated | Example |

|---|---|---|

| /x/ | /k/, /h/ | khabar, kabar "news" |

| /ð/ | /d/, /l/ | redha, rela "good will" |

| /zˤ/ | /l/, /z/ | lohor, zuhur "noon (prayer)" |

| /ɣ/ | /ɡ/, /r/ | ghaib, raib "hidden" |

| /ʕ/ | /ʔ/ | saat, sa'at "second (time)" |

| /θ/ | /s/ | Selasa "Tuesday" |

| /q/ | /k/ | makam "grave" |

Vowels

Malay originally had four vowels, but in many dialects today, including Standard Malay, it has six.[19] The vowels /e, o/ are much less common than the other four.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Open | a |

Orthographic note: both /e/ and /ə/ are written as 'e'. This means that there are some homographs, so perang can be either /pəraŋ/ ("war") or /peraŋ/ ("blond") (but in Indonesia perang with /e/ sound is also written as pirang).

Some analyses regard /ai, au, oi/ as diphthongs.[22][23] However, [ai] and [au] can only occur in open syllables, such as cukai ("tax") and pulau ("island"). Words with a phonetic diphthong in a closed syllable, such as baik ("good") and laut ("sea"), are actually two syllables. An alternative analysis therefore treats the phonetic diphthongs [ai], [au] and [oi] as a sequence of a monophthong plus an approximant: /aj/, /aw/ and /oj/ respectively.[24]

There is a rule of vowel harmony: the non-open vowels /i, e, u, o/ in bisyllabic words must agree in height, so hidung ("nose") is allowed but *hedung is not.[25]

| Johor-Riau

Pronunciation |

Northern

Pronunciation |

Baku & Indonesian

Pronunciation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ⟨a⟩ in final open syllable | /ə/ | /a/ | /a/ |

| ⟨i⟩ in final closed syllable with final ⟨n⟩ and ⟨ng⟩ | /e/ | /i/ | /i/ |

| ⟨i⟩ in final closed syllable with other final consonants | /e/ | /e/ | /i/ |

| ⟨u⟩ in final closed syllable with final ⟨n⟩ and ⟨ng⟩ | /o/ | /u/ | /u/ |

| ⟨u⟩ in final closed syllable with other final consonants | /o/ | /o/ | /u/ |

| final ⟨r⟩ | silent | /r/ | /r/ |

Grammar

Malay is an agglutinative language, and new words are formed by three methods: attaching affixes onto a root word (affixation), formation of a compound word (composition), or repetition of words or portions of words (reduplication). Nouns and verbs may be basic roots, but frequently they are derived from other words by means of prefixes, suffixes and circumfixes.

Malay does not make use of grammatical gender, and there are only a few words that use natural gender; the same word is used for 'he' and 'she' which is dia or for 'his' and 'her' which is dia punya. There is no grammatical plural in Malay either; thus orang may mean either 'person' or 'people'. Verbs are not inflected for person or number, and they are not marked for tense; tense is instead denoted by time adverbs (such as 'yesterday') or by other tense indicators, such as sudah 'already' and belum 'not yet'. On the other hand, there is a complex system of verb affixes to render nuances of meaning and to denote voice or intentional and accidental moods.

Malay does not have a grammatical subject in the sense that English does. In intransitive clauses, the noun comes before the verb. When there is both an agent and an object, these are separated by the verb (OVA or AVO), with the difference encoded in the voice of the verb. OVA, commonly but inaccurately called "passive", is the basic and most common word order.

Borrowed words

The Malay language has many words borrowed from Arabic (in particular religious terms), Sanskrit, Tamil, certain Sinitic languages, Persian (due to historical status of Malay Archipelago as a trading hub), and more recently, Portuguese, Dutch and English (in particular many scientific and technological terms).

Varieties and related languages

There is a group of closely related languages spoken by Malays and related peoples across Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Southern Thailand, and the far southern parts of the Philippines. They have traditionally been classified as Malay, Para-Malay, and Aboriginal Malay, but this reflects geography and ethnicity rather than a proper linguistic classification. The Malayan languages are mutually intelligible to varying extents, though the distinction between language and dialect is unclear in many cases.

Para-Malay includes the Malayan languages of Sumatra. They are: Minangkabau, Central Malay (Bengkulu), Pekal, Musi (Palembang), Negeri Sembilan (Malaysia), and Duano’.[27]

Aboriginal Malay are the Malayan languages spoken by the Orang Asli (Proto-Malay) in Malaya. They are Jakun, Orang Kanaq, Orang Seletar, and Temuan.

The other Malayan languages, included in neither of these groups, are associated with the expansion of the Malays across the archipelago. They include Malaccan Malay (Malaysian and Indonesian), Kedah Malay, Kedayan/Brunei Malay, Berau Malay, Bangka Malay, Jambi Malay, Kutai Malay, Loncong, Pattani Malay, and Banjarese. Menterap may belong here.

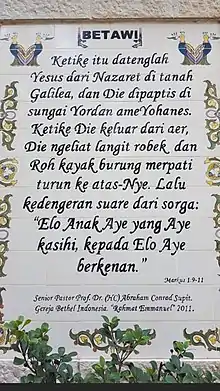

There are also several Malay-based creole languages, such as Betawi, Cocos Malay, Manado Malay and Sabah Malay, which may be more or less distinct from standard (Malaccan) Malay.

Due to the early settlement of a Cape Malay community in Cape Town, who are now known as Coloureds, numerous Classical Malay words were brought into Afrikaans.

Usages

The extent to which Malay and related Malayan languages are used in the countries where it is spoken varies depending on historical and cultural circumstances. Malay is the national language in Malaysia by Article 152 of the Constitution of Malaysia, and became the sole official language in West Malaysia in 1968, and in East Malaysia gradually from 1974. English continues, however, to be widely used in professional and commercial fields and in the superior courts. Other minority languages are also commonly used by the country's large ethnic minorities. The situation in Brunei is similar to that of Malaysia.

In Singapore, Malay was historically the lingua franca among people of different nationalities. Although this has largely given way to English, Malay still retains the status of national language and the national anthem, Majulah Singapura, is entirely in Malay. In addition, parade commands in the military, police and civil defence are given only in Malay.

Most residents of the five southernmost provinces of Thailand—a region that, for the most part, used to be part of an ancient Malay kingdom called Pattani—speak a dialect of Malay called Yawi (not to be confused with Jawi), which is similar to Kelantanese Malay, but the language has no official status or recognition.

Owing to earlier contact with the Philippines, Malay words—such as dalam hati (sympathy), luwalhati (glory), tengah hari (midday), sedap (delicious)—have evolved and been integrated into Tagalog and other Philippine languages.

By contrast, Indonesian has successfully become the lingua franca for its disparate islands and ethnic groups, in part because the colonial language, Dutch, is no longer commonly spoken. (In East Timor, which was governed as a province of Indonesia from 1976 to 1999, Indonesian is widely spoken and recognized under its Constitution as a 'working language'.)

Besides Indonesian, which developed from the Malaccan dialect, there are many Malay varieties spoken in Indonesia; they are divided into western and eastern groups. Western Malay dialects are predominantly spoken in Sumatra and Borneo, which itself is divided into Bornean and Sumatran Malay; some of the most widely spoken Sumatran Malay dialects are Riau Malay, Langkat, Palembang Malay and Jambi Malay. Minangkabau, Kerinci and Bengkulu are believed to be Sumatran Malay descendants. Meanwhile, the Jakarta dialect (known as Betawi) also belongs to the western Malay group.

The eastern varieties, classified either as dialects or creoles, are spoken in the easternmost part of the Indonesian archipelago and include Manado Malay, Ambonese Malay, North Moluccan Malay, and Papuan Malay.

The differences among both groups are quite observable. For example, the word kita means 'we, us' in western, but means 'I, me' in Manado, whereas 'we, us" in Manado is torang and Ambon katong (originally abbreviated from Malay kita orang 'we people'). Another difference is the lack of possessive pronouns (and suffixes) in eastern dialects. Manado uses the verb pe and Ambon pu (from Malay punya 'to have') to mark possession. So 'my name' and 'our house" are translated in western Malay as namaku and rumah kita but kita pe nama and torang pe rumah in Manado and beta pu nama, katong pu rumah in Ambon dialect.

The pronunciation may vary in western dialects, especially the pronunciation of words ending in the vowel 'a'. For example, in some parts of Malaysia and in Singapore, kita (inclusive 'we, us, our') is pronounced as /kitə/, in Kelantan and Southern Thailand as /kitɔ/, in Riau as /kita/, in Palembang as /kito/, in Betawi and Perak as /kitɛ/ and in Kedah and Perlis as /kitɑ/.

Batavian and eastern dialects are sometimes regarded as Malay creole, because the speakers are not ethnically Malay.

Examples

All Malay speakers should be able to understand either of the translations below, which differ mostly in their choice of wording. The words for 'article', pasal and perkara, and for 'declaration', pernyataan and perisytiharan, are specific to the Indonesian and Malaysian standards, respectively, but otherwise all the words are found in both (and even those words may be found with slightly different meanings).

| English | Malay | |

|---|---|---|

| Indonesian[28] | Standard "Malay"[29] | |

| Universal Declaration of Human Rights | Pernyataan Umum tentang Hak Asasi Manusia (General Declaration about Human Rights) | Perisytiharan Hak Asasi Manusia Sejagat (Universal Declaration of Human Rights) |

| Article 1 | Pasal 1 | Perkara 1 |

| All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. | Semua orang dilahirkan merdeka dan mempunyai martabat dan hak-hak yang sama. Mereka dikaruniai akal dan hati nurani dan hendaknya bergaul satu sama lain dalam semangat persaudaraan. (All human beings are born free and have the same dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should get along with each other in a spirit of brotherhood.) |

Semua manusia dilahirkan bebas dan sama rata dari segi maruah dan hak-hak. Mereka mempunyai pemikiran dan perasaan hati dan hendaklah bertindak di antara satu sama lain dengan semangat persaudaraan. (All human beings are born free and are equal in dignity and rights. They have thoughts and feelings and should get along with a spirit of brotherhood.) |

See also

- Comparison of Standard Malay and Indonesian

- Indonesian language

- Jawi script, an Arabic alphabet for Malay

- Languages of Indonesia

- List of English words of Malay origin

- Malajoe Batawi

- Malaysian English, the English used formally in Malaysia

- Malaysian language

References

- Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- Uli, Kozok (10 March 2012). "How many people speak Indonesian". University of Hawaii at Manoa. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

James T. Collins (Bahasa Sanskerta dan Bahasa Melayu, Jakarta: KPG 2009) gives a conservative estimate of approximately 200 million, and a maximum estimate of 250 million speakers of Malay (Collins 2009, p. 17).

- "Kedah MB defends use of Jawi on signboards". The Star. 26 August 2008. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012.

- "East Timor Languages". www.easttimorgovernment.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistic Student's Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- 10 million in Malaysia, 5 million in Indonesia as "Malay" plus 260 million as "Indonesian", etc.

- Wardhana, Dian Eka Chandra (2021). "Indonesian as the Language of ASEAN During the New Life Behavior Change 2021". Journal of Social Work and Science Education. 1 (3): 266–280. doi:10.52690/jswse.v1i3.114. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Adelaar (2004)

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (2001). "The Search for the 'Origins' of Melayu" (PDF). Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 32 (3): 315–330. doi:10.1017/S0022463401000169. S2CID 62886471.

- Wurm, Stephen; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Vol I: Maps. Vol II: Texts. Walter de Gruyter. p. 677. ISBN 978-3-11-081972-4.

- "Bahasa Melayu Kuno". Bahasa-malaysia-simple-fun.com. 15 September 2007. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- Surakhman, M. Ali (23 October 2017). "Undang-Undang Tanjung Tanah: Naskah Melayu Tertua di Dunia". kemdikbud.go.id (in Indonesian).

- Sneddon, James N. (2003). The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society. UNSW Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-86840-598-8.

- Sneddon, James N. (2003). The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society. UNSW Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-86840-598-8.

- Ethnologue 16 classifies them as distinct languages, ISO3 kxd and meo, but states that they "are so closely related that they may one day be included as dialects of Malay".

- "Malay (Bahasa Melayu)". Omniglot. Retrieved 30 August 2008.

- "Malay Can Be 'Language of ASEAN'". brudirect.com. 24 October 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- Salleh, Haji (2008). An introduction to modern Malaysian literature. Kuala Lumpur: Institut Terjemahan Negara Malaysia Berhad. pp. xvi. ISBN 978-983-068-307-2.

- Clynes, Adrian; Deterding, David (2011). "Standard Malay (Brunei)". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 41 (2): 259–268. doi:10.1017/S002510031100017X..

- Karim, Nik Safiah; M. Onn, Farid; Haji Musa, Hashim; Mahmood, Abdul Hamid (2008). Tatabahasa Dewan (in Malay) (3 ed.). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. pp. 297–303. ISBN 978-983-62-9484-5.

- Soderberg, Craig D.; Olson, Kenneth S. (2008). "Indonesian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 38 (2): 209–213. doi:10.1017/S0025100308003320. ISSN 1475-3502.

- Asmah Haji, Omar (1985). Susur galur bahasa Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- Ahmad, Zaharani (1993). Fonologi generatif: teori dan penerapan. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- Clynes, Adrian (1997). "On the Proto-Austronesian "Diphthongs"". Oceanic Linguistics. 36 (2): 347–361. doi:10.2307/3622989. JSTOR 3622989.

- Adelaar, K. A. (1992). Proto Malayic: the reconstruction of its phonology and parts of its lexicon and morphology (PDF). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. doi:10.15144/pl-c119. ISBN 0858834081. OCLC 26845189.

- Abu Bakar, Mukhlis (18 December 2019). "Sebutan Johor-Riau dan Sebutan Baku dalam Konteks Identiti Masyarakat Melayu Singapura". Issues in Language Studies. 8 (2). doi:10.33736/ils.1521.2019. ISSN 2180-2726. S2CID 213343934.

- Ethnologue 16 also lists Col, Haji, Kaur, Kerinci, Kubu, Lubu'.

- Standard named as stated in:

"Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - The other language standard aside from "Indonesian" is named simply as "Malay", as stated in: "Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Bahasa Melayu (Malay))". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Further reading

- Adelaar, K. Alexander (2004). "Where does Malay come from? Twenty years of discussions about homeland, migrations and classifications". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 160 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003733. JSTOR 27868100.

- B., C. O. (1939). "Corrigenda and Addenda: A Chinese Vocabulary of Malacca Malay Words and Phrases Collected between A.D. 1403 and 1511 (?)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 10 (1). JSTOR 607921.

- Braginsky, Vladimir, ed. (2013) [First published 2002]. Classical Civilizations of South-East Asia. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-84879-7.

- Edwards, E. D.; Blagden, C. O. (1931). "A Chinese Vocabulary of Malacca Malay Words and Phrases Collected between A. D. 1403 and 1511 (?)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 6 (3): 715–749. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00093204. JSTOR 607205. S2CID 129174700.

- Wilkinson, Richard James (1901–1903). A Malay-English Dictionary. Singapore: Kelly & Walsh.

External links

- Swadesh list of Malay words

- Digital version of Wilkinson's 1926 Malay-English Dictionary

- Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu, online Malay language database provided by the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka

- Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia dalam jaringan (Online Great Dictionary of the Indonesian Language published by Pusat Bahasa, in Indonesian only)

- Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (Institute of Language and Literature Malaysia, in Malay only)

- The Malay Spelling Reform, Asmah Haji Omar, (Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society, 1989-2 pp. 9–13 later designated J11)

- Malay Chinese Dictionary

- Malay English Dictionary

- Malay English Translation