Mannheim

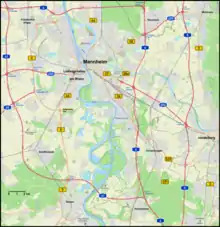

Mannheim (German pronunciation: [ˈmanhaɪm] (![]() listen); Palatine German: Mannem[4] or Monnem), officially the University City of Mannheim (German: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's 21st-largest city, with a 2020 population of 309,119 inhabitants.[5] The city is the cultural and economic centre of the Rhine-Neckar Metropolitan Region, Germany's seventh-largest metropolitan region with nearly 2.4 million inhabitants and over 900,000 employees.[6]

listen); Palatine German: Mannem[4] or Monnem), officially the University City of Mannheim (German: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's 21st-largest city, with a 2020 population of 309,119 inhabitants.[5] The city is the cultural and economic centre of the Rhine-Neckar Metropolitan Region, Germany's seventh-largest metropolitan region with nearly 2.4 million inhabitants and over 900,000 employees.[6]

Mannheim | |

|---|---|

City | |

Clockwise from top: Friedrichsplatz, Luisenpark, Augustaanlage, Mannheim Palace, Mannheim Water Tower (Wasserturm), Jesuit Church | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Location of Mannheim in Baden-Württemberg  | |

Mannheim  Mannheim | |

| Coordinates: 49°29′16″N 08°27′58″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Baden-Württemberg |

| Admin. region | Karlsruhe |

| District | Urban district |

| Founded | 1607 |

| Subdivisions | 17 Stadtbezirke |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2015–23) | Peter Kurz[1] (SPD) |

| Area | |

| • City | 144.96 km2 (55.97 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 97 m (318 ft) |

| Population (2020-12-31)[2] | |

| • City | 309,721 |

| • Density | 2,100/km2 (5,500/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,362,046 (2,012)[3] |

| Demonym | Mannheimer |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 68001–68309 |

| Dialling codes | 0621 |

| Vehicle registration | MA |

| Website | www.mannheim.de |

Mannheim is located at the confluence of the Rhine and the Neckar in the Kurpfalz (Electoral Palatinate) region of northwestern Baden-Württemberg. The city lies in the Upper Rhine Plain, Germany's warmest region. Together with Hamburg, Mannheim is the only city bordering two other federal states. It forms a continuous conurbation of around 480,000 inhabitants with Ludwigshafen am Rhein in the neighbouring state of Rhineland-Palatinate, on the other side of the Rhine. Some northern suburbs of Mannheim belong to Hesse. Upstream along the Neckar lies Heidelberg, the fifth-largest city of Baden-Württemberg and the third-largest of the Rhine-Neckar Region.

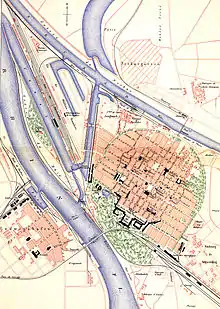

Mannheim is unusual among German cities in that the city center's streets and avenues are laid out in a grid pattern, leading to its nickname Quadratestadt (Square City). Within a ring of avenues surrounding the city centre, there are squares numbered from A1 to U6 instead of street names. At the southern base of that system sits Mannheim Palace, one of the largest palace complexes in the world, and the second-largest in Baroque style after Versailles. It was the former home of the Prince-elector of the Electoral Palatinate, and now houses the University of Mannheim, which repeatedly receives top marks in business administration and is sometimes known as the "Harvard of Germany".[7][8][9] The Mannheim May Market is the largest regional consumer exhibition of Germany.[10] The civic symbol of Mannheim is the Romanesque Mannheim Water Tower, completed in 1886 and rising to 60 metres (200 feet) above the highest point of the art nouveau area Friedrichsplatz. Mannheim is well-known for its inventions, including the automobile,[11][12] the bicycle,[13][12] and the tractor,[12] which is why the city is often called the "city of inventions".[14][15][16] The city is the starting and finishing point of the Bertha Benz Memorial Route that follows the tracks of the first long-distance automobile trip in history.

A Großstadt (major city with more than 100,000 inhabitants) since 1896,[17] Mannheim is now an important industrial and commercial city, a university town, and a major transportation hub between Frankfurt and Stuttgart, including an ICE interchange (the Mannheim Hauptbahnhof), Germany's second-largest marshalling yard[18] (the Mannheim Rangierbahnhof), and one of the most important inland ports in Europe (the Mannheim Harbour). The city is home to many factories, offices and headquarters of several major corporations such as Roche, ABB, IBM, Siemens, Unilever and more. Mannheim's SAP Arena is home to German ice hockey record champions Adler Mannheim as well as popular handball team Rhein-Neckar Löwen. Since 2014, Mannheim has been a member of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network and holds the title of "UNESCO City of Music".[19] In 2020, Mannheim was classified as a global city with 'Sufficiency' status by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC).[20] Mannheim is a smart city;[21] the city's electrical grid is installed with a power-line communication network.[22] The city's tourism slogan is "Leben im Quadrat" ("Life in the[lower-alpha 1] Square").[23]

History

Early history

A brick kiln excavated in 1929 in the Seckenheim district, which operated from 74 AD to the early second century, attests to settlement in Roman times.[24]

The name of the city was first recorded as Mannenheim in a legal transaction in 766, surviving in a twelfth-century copy in the Codex Laureshamensis from Lorsch Abbey.[25] The name is interpreted as "the home of Manno", a short form of a Germanic name such as Hartmann or Hermann.[26] Mannheim remained a mere village throughout the Middle Ages.

Early Modern Age

In 1606, Frederick IV, Elector Palatine started building the fortress of Friedrichsburg and the adjacent city centre with its grid of streets and avenues. On 24 January 1607, Frederick IV gave Mannheim the status of a "city",[27] whether it really was one by then or not.

Mannheim was mostly levelled during the Thirty Years War around 1622 by the forces of Johan Tilly. After being rebuilt, it was again severely damaged by the French Army in 1689 during the Nine Years' War.

After the rebuilding of Mannheim that began in 1698, the capital of the Electorate of the Palatinate was moved from Heidelberg to Mannheim in 1720[28] when Karl III Philip, Elector Palatine began construction of Mannheim Palace and the Jesuit Church; they were completed in 1760.

18th and 19th centuries

During the eighteenth century, Mannheim was the home of the "Mannheim School" of classical music composers. Mannheim was said to have one of the best court orchestras in Europe under the leadership of the conductor Carlo Grua. The royal court of the Palatinate left Mannheim in 1778. Two decades later, in 1802, Mannheim was removed from the Palatinate and given to the Grand Duchy of Baden.

In 1819, Norwich Duff wrote of Mannheim:

Mannheim is in the Duchy of Baden and situated at the confluence of the Rhine and Neckar over both of which there is a bridge of boats. This is the third town of this name having been twice burnt. The houses are large, and the streets broad and at right angles to each other, and is one of the most airy clean towns I have seen in Germany. It was formerly fortified, but the fortifications were razed in 1806 and gardens fill their places. There is a large château here belonging to the Grand Duke and a very good garden; part of the château was destroyed when the town was bombarded and has never since been repaired, the other part is occupied by the Grand Duchess, widow of the late Grand Duke who was succeeded by his uncle having left only three daughters. She is the sister of Eugene Beauharnais [sic; in fact, she was his second cousin]. There is a cathedral, a theatre which is considered good, an observatory, a gallery of pictures at the château, and some private collections. About two kilometres (one point two miles) below the town the Russian Army crossed the Rhine in 1813. Population 18,300.

In 1819, August von Kotzebue was assassinated in Mannheim.

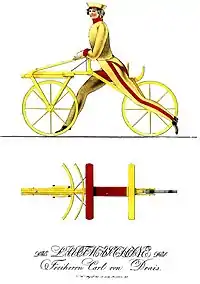

The climate crisis of 1816-17 caused famine and the death of many horses in Mannheim. That year Karl Drais invented the first bicycle.

Infrastructure improvements included the establishment of Rhine Harbour in 1828 and construction of the first Baden railway, which opened from Mannheim to Heidelberg in 1840. Influenced by the economic rise of the middle class, another golden age of Mannheim gradually began. In the March Revolution of 1848, the city was a centre for political and revolutionary activity.

In 1865, Friedrich Engelhorn founded the Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik (Baden Aniline and Soda Factory, BASF) in Mannheim, but the factory was constructed across the Rhine in Ludwigshafen because Mannheim residents feared air pollution from its operations. From this dye factory, BASF has developed into the largest chemical company in the world. After opening a workshop in Mannheim in 1871 and patenting engines from 1878, Karl Benz patented the first motor car in 1886. He was born in Mühlburg (now part of Karlsruhe).

Early 20th century and World War I

The Schütte-Lanz company, founded by Karl Lanz and Johann Schütte in 1909, built 22 airships. The company's main competitor was the Zeppelin works.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Mannheim's industrial plants played a key role in Germany's war economy. This contributed to the fact that, on 27 May 1915, Ludwigshafen was the world's first civilian settlement behind the battle lines to be bombed from the air. French aircraft attacked the BASF plants, thereby killing twelve people. The precedent was set for this attack by Germany's repeated air raids against British civilian populations throughout southeastern Britain during the first half of 1915.

When Germany lost the war in 1918, according to the peace terms, the left bank of the Rhine was occupied by French troops. The French occupation lasted until 1930, and some of Ludwigshafen's most elegant houses were erected for the officers of the French garrison.

Inter-war period

After the First World War, the Heinrich Lanz Company built the Bulldog, an advanced tractor, powered by heavy oil. As a result of the invention of the pre-combustion chamber by Prosper L'Orange, Benz & Cie. developed the world's first compact diesel-powered car at its motor works in Mannheim in 1923. In 1922, the Grosskraftwerk Mannheim (Mannheim large power station) was opened. By 1930, the city, along with its sister city of Ludwigshafen, which had developed out of the old Mannheim Rheinschanze, had a population of 385,000.

World War II

During World War II, air raids on Mannheim completely destroyed the city centre. Mannheim was heavily damaged during aerial bombing by the RAF and the U.S. Air Force. The RAF razed the city center of Mannheim with nighttime area bombing, killing thousands of civilians. 2,262 of Mannheim's Jews were sent to concentration camps. Some sources state that the first deliberate terror bombing of the war occurred at Mannheim on 16 December 1940.[29]

The Allied ground advance into Germany reached Mannheim in late March 1945, which was potentially well-defended by German forces. However, the German forces suddenly abandoned the city and the U.S. 44th Infantry Division entered unopposed on 29 March 1945.[30] There had been a large American military occupation presence in the Mannheim area with up to 10 barracks. The first one shut down in 2007 going on until 2013 when the last one closed. (See United States military installations below).

1950s to 1980s

Rebuilding of the city began laboriously. Mannheim Palace and the water tower (Wasserturm) eventually were rebuilt and the National Theatre was replaced by a new building at a new location. At the old location there is a monument to Friedrich Schiller and the Zum Zwischen-Akt pub. The housing shortage led to the development of many new residential areas.

In 1964, the City Hospital (Städtisches Krankenhaus) became part of the Heidelberg University for Clinical Medicine in Mannheim. In 1967, the University of Mannheim was established in the city.

In 1975, the Bundesgartenschau (Federal horticulture show) was celebrated in Luisen and Herzogenried parks. A number of pieces of infrastructure were developed for the show: the telecommunications tower and a second bridge across the Rhine were built, the pedestrian zone was established, the new Rosengarten conference centre was opened and the Aerobus was installed as a temporary transport system.

A number of major projects were completed in the 1980s and 1990s: a planetarium, an extension to the art gallery, the new Reiß Museum, Stadthaus, a new May Market ground, synagogue, mosque, State Museum for Technology and Work, Carl-Benz stadium and the Fahrlach tunnel were opened.

Mannheim has lost many industrial jobs, although in the recent past the city was economically dominated by manufacturing. The city tried in the past to prevent the establishment of service providers by designating some locations as industrial areas. A prime example of the current trend is the construction of the Victoria Tower (Victoria-Turm) in 2001, one of the tallest buildings in the city, on railway land.

Post-reunification

Mannheim celebrated its 400th anniversary with a series of cultural and other events throughout 2007. The 400th anniversary proper was in 2006, since Frederick IV, Elector Palatine laid the foundations of Mannheim citadel on 17 March 1606. In preparation for the anniversary, some urban activities were implemented, beginning in 2000: the building of the SAP Arena with access to the city's new eastern ring road, the rehabilitation of the pedestrian zone in Breite Straße, the arsenal and the palace, the complete transformation of the old fair ground, and the new Schafweide tram line. The concept of the anniversary of the city aimed at a diverse range of events without a dominant central event. In 2001, the City hospital was officially and legally awarded with the title University Hospital Mannheim.

Geography

Climate

| Climate data for Mannheim, Germany for 1981–2010 (Source: DWD) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.2 (91.8) |

38.9 (102.0) |

39.0 (102.2) |

39.8 (103.6) |

34.3 (93.7) |

28.5 (83.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

39.8 (103.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

15.50 (59.90) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

10.85 (51.53) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

-0.0 (32.0) |

6.28 (43.30) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −18.7 (−1.7) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

4.7 (40.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 40.9 (1.61) |

43.1 (1.70) |

50.8 (2.00) |

49.3 (1.94) |

72.5 (2.85) |

66.6 (2.62) |

76.0 (2.99) |

57.7 (2.27) |

54.1 (2.13) |

56.4 (2.22) |

53.5 (2.11) |

54.1 (2.13) |

675.0 (26.57) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 55.2 | 85.6 | 124.0 | 180.2 | 214.1 | 219.1 | 235.1 | 222.1 | 164.1 | 108.8 | 59.0 | 44.9 | 1,712.2 |

| Source: Data derived from Deutscher Wetterdienst[31] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mannheim 2019-present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

6.1 (43.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.0 (60.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

6.0 (42.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

12.2 (53.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

6.9 (44.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 15.6 (0.61) |

49.3 (1.94) |

35.7 (1.41) |

22.6 (0.89) |

55.4 (2.18) |

81.4 (3.20) |

38.3 (1.51) |

63.3 (2.49) |

77.1 (3.04) |

89.9 (3.54) |

48.6 (1.91) |

52.3 (2.06) |

629.5 (24.78) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 4.0 (1.6) |

1.6 (0.6) |

1.2 (0.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.0 (0.4) |

2.0 (0.8) |

5.6 (2.2) |

2.6 (1.0) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 57.3 | 116.2 | 164.0 | 251.2 | 247.9 | 268.1 | 286.1 | 248.9 | 199.1 | 97.5 | 38.2 | 53.4 | 2,027.9 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst[32] | |||||||||||||

Mannheim is located in Germany's warmest summer region, the "Rhine shift". In summer, temperatures sometimes rise up to 35 °C (95 °F) and higher. The highest recorded temperature was 39.8 °C (104 °F) on 7 August 2015. The daily lows during heat waves can be very high by north European standards (around 25 °C / 77 °F). In September 2016, the average temperature in Mannheim was 18.6 °C, highest in Baden-Württemberg.[33]

In comparison to other regions of Germany, Mannheim has a higher humidity in summer which causes a higher heat index. Snow is rare, even in the cold months. Precipitation occurs mostly during afternoon thunderstorms during the warmer period (average days of thunderstorms in a year is 40–50). Climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year-round. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Cfb" (Marine West Coast Climate/Oceanic climate).[34]

Demographics

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1450 | 570 | — |

| 1663 | 3,000 | +426.3% |

| 1777 | 25,353 | +745.1% |

| 1802 | 18,818 | −25.8% |

| 1871 | 39,606 | +110.5% |

| 1900 | 141,131 | +256.3% |

| 1919 | 229,576 | +62.7% |

| 1925 | 247,486 | +7.8% |

| 1933 | 275,162 | +11.2% |

| 1939 | 284,957 | +3.6% |

| 1950 | 245,634 | −13.8% |

| 1961 | 313,890 | +27.8% |

| 1970 | 332,163 | +5.8% |

| 1987 | 295,191 | −11.1% |

| 2011 | 290,117 | −1.7% |

| 2017 | 307,997 | +6.2% |

| Source:[35] | ||

Nationalities

The following list shows significant groups of foreigners in the city of Mannheim by nationalities.[36] In total 44,7% of all Mannheim inhabitants are from foreign descent. With 68,9% in the Neckarstadt-West district the population is the most foreign, in the Wallstadt district with 23,1% it is the least. A large part of the immigrants are from the Balkans and European countries.

| Rank | Nationality | Population (31 December 2020) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Turkey | At least 2 (5.12%) |

| 2 | Italy | 8,165 (2.65%) |

| 3 | Bulgaria | 6,997 (2.27%) |

| 4 | Poland | 6,595 (2.14%) |

| 5 | Romania | 5,663 (1.83%) |

| 6 | Croatia | 4,565 (1.48%) |

| 7 | Greece | 3,341 (1.08%) |

| 8 | Spain | 1,754 (0.56%) |

| 9 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1,680 (0.54%) |

| 10 | Syria | 1,642 (0.53%) |

| 11 | India | 1,541 (0.5%) |

| 12 | Hungary | 1,341 (0.43%) |

| 13 | France | 1,266 (0.41%) |

| 14 | Kosovo | 1,164 (0.37%) |

| 15 | Serbia | 1,023 (0.33%) |

| 16 | China | 1,022 (0.33%) |

| 18 | United States | 933 (0.30%) |

| 19 | Yugoslavia | 876 (0.28%) |

| 20 | Iraq | 831 (0.27%) |

Religion

The distribution of Mannheim's population by religious affiliation (as of December 31, 2020) is Roman Catholic 25.4%, Protestant 20.0%, and other/none 54.6%.[37]

Theatre

The National Theatre Mannheim was founded in 1779 and is the oldest "Stage" in Germany. In 1782 the premiere of Die Räuber, written by Friedrich Schiller, was shown.[38]

Recently, more smaller stages have opened, such as the Oststadt-Theater, the TIG7 (Theater im Quadrat G7), the Theater Oliv, the Freilichtbühne, the Theater31, the Theater ImPuls, the Theater Felina-Areal, the Mannheimer Puppenspiele, the Kleinkunstbühne Klapsmühl', Schatzkistl, and zeitraumexit.

Sport

There are two nationally renowned football clubs in Mannheim, SV Waldhof Mannheim, who currently are playing in the third tier 3. Liga, but who have played in the top tier, the Bundesliga; and VfR Mannheim, winner of the German championship in 1949, now playing in the sixth tier Verbandsliga Baden.

The Adler Mannheim (formerly MERC, Mannheimer Eis- und Rollsport-Club) is an ice hockey team playing in the professional Deutsche Eishockey Liga, having won the German championship a total of eight times (7 times Deutsche Eishockey Liga and one time the former highest German ice hockey league known as Bundesliga).[39]

The city is home to the Mannheim Tornados, the oldest operational baseball and softball club in Germany. The Tornados play in the first division of the Baseball Bundesliga and have won the championship 11 times, more than any other club.[40]

In 2003, the American football club Mannheim Bandits was founded. The Mannheim Bandits are playing in the first German Football League which is called GFL1. As of 2018, between 500 and 900 people watch each game.[41]

Rhein-Neckar Löwen are a handball team playing in the professional German Handball League.[42]

The WWE visited Mannheim in 2008. Around 10,000 fans attended the event.[43]

UFC fighter Dennis Siver lives and trains in Mannheim.[44]

Mannheim hosted the European Show Jumping Championships in 1997, and the FEI European Jumping Championships in 2007[45] 14–19 August, in the MVV-riding stadium.

In 2002, Hobby Horse Polo was invented in Mannheim, evoking the classical rivalry towards "polite society" in Heidelberg.[46][47][48]

The Maimarkt-Turnier Mannheim is an annual international horse show held during the Mannheimer Maimarkt since 1964.

Education

The University of Mannheim is one of Germany's younger universities. Although founded in 1967, it has its origins in the Palatine Academy of Sciences, established in 1763, and the former Handelshochschule (Commercial College), founded in 1907. Situated in Mannheim Palace, it is Germany's leading university in the fields of business and economics and attracts students from around the world. Described by Die Zeit as the 'Harvard of Germany',[7] it is seen as the training grounds of German business leaders. More than 12,000 students were enrolled in the 2013/14 semester.[49]

The university town also houses one of the medical schools of Heidelberg University (at the University Hospital Mannheim), the Hochschule Mannheim, a branch of the Duale Hochschule of the State of Baden-Württemberg and several musical and theatrical academies, including the Pop Academy Mannheim, the Musikhochschule and the Theaterakademie. These institutions draw a large and diverse student body.

Dependents of U.S. military personnel attended Mannheim Elementary School until it closed in June 2012.[50] In the 1980s the school had 2,200 students.[51]

Inventions

According to Forbes magazine, Mannheim is known for its exceptional inventive power and was ranked 11th among the Top 15 of the most inventive cities worldwide.[52]

Many significant inventions were made in Mannheim:

- Karl Drais built the first two-wheeled draisine in 1817.

- Karl Benz drove the first automobile on the streets of Mannheim in 1886. At his workshop in Mannheim he produced a lightweight three-wheeled vehicle powered by a single cylinder petrol/gasoline-fueled engine, first shown in public during 1886. This powered tricycle subsequently came to be widely regarded as the first automobile/motor car powered by an internal-combustion engine. Karl's wife Bertha Benz undertook the world's first road trip by automobile from Mannheim to Pforzheim and back,[53] about 65 miles then, on modern roads about 55 miles, in August 1888.

- The Lanz Bulldog, a popular tractor with a rugged, simple Diesel engine was introduced in 1921.

- Karl Benz developed the world's first compact diesel-powered car at the Benz & Cie. motor works in Mannheim during 1923.

- Julius Hatry built the world's first rocket plane in 1929.

The world's first bicycle, built in Mannheim by Karl Freiherr von Drais in 1817

The world's first bicycle, built in Mannheim by Karl Freiherr von Drais in 1817 The world's first motorcar, built in Mannheim by Karl Benz in 1885

The world's first motorcar, built in Mannheim by Karl Benz in 1885 Official sign of Bertha Benz Memorial Route, commemorating the world's first long-distance journey by automobile from Mannheim to Pforzheim in 1888 104 km (65 mi)

Official sign of Bertha Benz Memorial Route, commemorating the world's first long-distance journey by automobile from Mannheim to Pforzheim in 1888 104 km (65 mi)

Government and politics

Mayor

.svg.png.webp)

The mayor is the head of the city council and chairman of the council, being selected by direct suffrage for a term of eight years. The current mayor is Peter Kurz from the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), who was elected during 2007 with 50.53 percent on a turnout of 36.64 percent in the first round. He was reelected in 2015. The most recent mayoral election was held on 14 June 2015, with a runoff held on 5 July, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Peter Kurz | Social Democratic Party | 33,323 | 46.8 | 34,563 | 52.0 | |

| Peter Rosenberger | Christian Democratic Union | 24,098 | 33.8 | 29,830 | 44.9 | |

| Christopher Probst | Free Voters/Mannheimer List | 11,354 | 15.9 | Withdrew | ||

| Christian Sommer | Die PARTEI | 2,327 | 3.3 | 1,920 | 2.9 | |

| Other | 123 | 0.2 | 112 | 0.2 | ||

| Valid votes | 71,225 | 99.1 | 66,425 | 99.3 | ||

| Invalid votes | 641 | 0.9 | 499 | 0.7 | ||

| Total | 71,866 | 100.0 | 66,924 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 234,081 | 30.7 | 233,134 | 28.7 | ||

| Source: City of Mannheim | ||||||

The city leaders since 1810 are:

- 1810–1820: Johann Wilhelm Reinhardt

- 1820–1832: Valentin Möhl

- 1833–1835: Heinrich Andriano

- 1836–1849: Ludwig Jolly

- 1849–1852: Friedrich Reiß

- 1852–1861: Heinrich Christian Diffené

- 1861–1870: Ludwig Achenbach

- 1870–1891: Eduard Moll

- 1891–1908: Otto Beck

- 1908–1913: Paul Martin

- 1914–1928: Theodor Kutzer

- 1928–1933: Hermann Heimerich (SPD)

- 1933–1945: Carl Renninger (NSDAP)

- 1945–1948: Josef Braun (CDU)

- 1948–1949: Fritz Cahn-Garnier (SPD)

- 1949–1955: Hermann Heimerich (SPD)

- 1956–1972: Hans Reschke (independent)

- 1972–1980: Ludwig Ratzel (SPD)

- 1980–1983: Wilhelm Varnholt (SPD)

- 1983–2007: Gerhard Widder (SPD)

- 2007–present: Peter Kurz (SPD)

City council

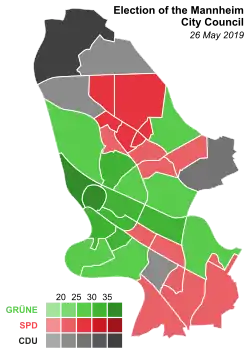

The council has 48 seats and is elected by direct suffrage for five years. In the local elections in Baden-Württemberg, voters are allowed to take advantage of cumulative voting and vote splitting. Since the Second World War the SPD, except in the elections of 1999 and 2004, has received more votes than the CDU. At the 2019 election the Greens received most votes for the first time. The next municipal election will take place in 2024.

The most recent city council election was held on 26 May 2019, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 1,235,924 | 24.4 | 12 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 1,071,597 | 21.2 | 10 | |||

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 968,098 | 19.1 | 9 | |||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 465,694 | 9.2 | 4 | ±0 | ||

| Free Voters/Mannheimer List (ML) | 372,461 | 7.4 | 4 | ±0 | ||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 307,305 | 6.1 | 3 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 302,685 | 6.0 | 3 | ±0 | ||

| Die PARTEI (PARTEI) | 151,449 | 3.0 | New | 1 | New | |

| Middle-Class for Mannheim (MfM) | 67,163 | 1.3 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Human Environment Animal Protection (Tierschutzpartei) | 55,458 | 1.1 | New | 1 | New | |

| Mannheimer People's Party (MVP) | 27,491 | 0.5 | New | 0 | New | |

| Alliance for Innovation and Justice (BIG) | 22,928 | 0.5 | New | 0 | New | |

| National Democratic Party (NPD) | 13,784 | 0.3 | New | 0 | New | |

| Total | 5,062,037 | |||||

| Total ballots | 118,721 | 100.0 | 48 | ±0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 238,496 | 49.8 | ||||

| Source: City of Mannheim | ||||||

United States military installations

A number of U.S. Army Europe installations were located in and near Mannheim during the Cold War. The following locations provided services to and housed the "U.S. Army Garrison Mannheim" and other units of the U.S. Army. The U.S. Army Garrison Mannheim was formally deactivated on 31 May 2011.[54]

- Coleman Barracks and Coleman Army Airfield (Mannheim-Sandhofen): The headquarters of the American Forces Network-Europe, and the home of the Army's 28th Transportation Battalion. Also, the location of the United States Army Corrections Facility-Europe.

- Funari Barracks (Mannheim-Käfertal), vacated in 2014.

- Spinelli Barracks (Mannheim-Feudenheim), vacated in 2015.

- Sullivan Barracks (Mannheim-Käfertal): formerly the headquarters of the U.S. Army's 7th Signal Brigade and the 529th Military Police Honor Guard Company's 2nd Platoon; vacated in 2014.

- Taylor Barracks (Mannheim-Vogelstang): formerly the headquarters of the U.S. Army's 2nd Signal Brigade; vacated in 2011.

- Turley Barracks (Mannheim-Käfertal): in the early 1990s was home to the 181st Transportation Bn, with companies of 40th, 41st, 51st, 590th, TTP, and HHC transportation companies and also the headquarters of the NATO ACE Mobile Force (Land) (AMFL).

- The Benjamin Franklin Village (Mannheim-Käfertal), housing. Also, it was the home of the Mannheim American High School and the Middle School,[55] which closed on 9 June 2011. The last soldier and his family moved out in 2012.

The following locations were part of the "U.S. Army Garrison Heidelberg" but were within the area of the city of Mannheim; They were vacated in 2010 and 2011:

- Friedrichsfeld Service Center (Mannheim-Friedrichsfeld)

- Hammonds Barracks (formerly Loretto Kaserne) (Mannheim-Seckenheim)

- Stem Kaserne (Mannheim-Seckenheim)

All personnel of the U.S. Army military community left Mannheim by 2015, some of them moving to Wiesbaden. With the exception of four barracks, all other barracks formerly occupied by the U.S. military had been returned to the German state for conversion to civilian use in 2011.

Main sights

- Fernmeldeturm Mannheim – 217.8-metre-high telecommunication tower, landmark of Mannheim

- Synagoge (Mannheim) – post World War II synagogue

- Yavuz Sultan Selim Mosque

- Luisenpark – named one of the most beautiful parks in Europe with around 1.2 million visitors annually[56]

- Mannheim Palace (Mannheimer Schloss) – the city castle and main building of the University of Mannheim

- Wasserturm – the town's landmark water tower

- Jesuit Church

- SAP Arena – multifunctional indoor arena, home of Mannheim's ice-hockey team "Die Adler" ("The Eagles")[57]

- Breite Strasse, Kunststrasse, and Kapuzinerplanken – Mannheim's main shopping destinations

- International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg

- Kunsthalle Mannheim – museum of modern and contemporary art

- Technoseum – technology museum

- Multihalle - multi-purpose hall in Mannheim's Herzogenriedpark, the world's largest self-supporting wooden lattice-shell construction

- Wildpark and Waldvogelpark am Karlstern

- The city centre – designed in squares (Quadratestadt)

- Reißinsel – a natural area that an honorary citizen of Mannheim, Carl Reiß, bequeathed to the residents of Mannheim[58]

- Reiß-Engelhorn-Museen – museum with four exhibition halls presenting exhibits in archaeology, world cultures, history of art and culture, photography, and history of theater and music

- Maimarkt – largest regional trade fair in Germany[59]

- Marktplatz (Market square) – hosts a farmers' market every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday.[60] Fresh fruit, vegetables, and flowers are sold.

- Mannheimer Mess (Mannheim Fair) – twice a year (spring & autumn), a big fair that takes place on Neuer Messplatz-square.[61]

Economy

With a gross domestic product (GDP) of €20.921 billion, Mannheim ranks 17th on the list of German cities by GDP as of 2018.

In the 2019 edition of the Zukunftsatlas, the independent city of Mannheim ranked 35nd out of 401 counties and independent cities in Germany, making it one of the places with "high future opportunities".[62]

Mannheim is among the most attractive business locations in Germany thanks to its competitive business environment and growth opportunities and is considered the economic centre of the Rhine-Neckar Metropolitan Region, which is one of Germany's most important business locations.[21]

The New Economy Magazine elected Mannheim under the 20 cities that best represent the world of tomorrow emphasizing Mannheim's positive economic and innovative environment.[21]

The unemployment rate of Mannheim is 7.2% as of 2020.[63]

The successor to the Karl Benz automobile manufacturing companies begun in Mannheim, Daimler AG, has had a large presence in Mannheim. Today, diesel engines and buses are assembled there. The Swiss Hoffmann–La Roche diagnostic group (formerly known as Boehringer Mannheim) has its division headquarters in Mannheim.[64] Additionally, the city also hosts large factories, headquarters and/or offices of ABB,[65] IBM,[66] Alstom,[67][68] BASF (Ludwigshafen), Bilfinger Berger,[69] Reckitt Benckiser, Unilever,[70] Essity,[71] Phoenix Group,[72] Bombardier,[73] Pepperl+Fuchs,[74] Caterpillar, Fuchs Petrolub AG, John Deere, Siemens,[75] SCA, Südzucker, and other companies. The University Hospital Mannheim provides health care to the inhabitants of Mannheim and the Rhine-Neckar Metropolitan Region.

With €4.5 billion, Mannheim ranks 22nd on the list of cities by market value of its DAX, TecDAX and MDAX companies.[76]

MVV Energie based in Mannheim is the largest municipal energy supplier in Germany.

Media

In addition to the only local daily newspaper Mannheimer Morgen, the Ludwigshafen newspaper Die Rheinpfalz, the Heidelberg newspaper Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung and the Bild Rhein-Neckar offer a local section for Mannheim. In addition, the weekly paper Wochenblatt Mannheim with its official gazette is published. The Kommunal-Info Mannheim is published fortnightly. Free district newspapers are distributed in almost all parts of the city.

Infrastructure

Road transport

The Mannheim/Ludwigshafen area is surrounded by a ring of motorways connecting it to Frankfurt in the north, Karlsruhe in the south, Saarbrücken in the west and Nuremberg in the east.

Railway transport

Mannheim Hauptbahnhof (central station) is at the end of the Mannheim-Stuttgart high-speed rail line and is the most important railway junction in the southwest of Germany, served by ICE high-speed train system with connections to Frankfurt am Main–Berlin, Karlsruhe–Basel, and Stuttgart–Munich. A new high speed line to Frankfurt also is planned to relieve the existing Mannheim–Frankfurt railway.[77]

River transport

Mannheim Harbour is the second-largest river port in Germany. It has a size of 1131 hectare.[78] In 2016, 6.9 million tons of goods were handled on the water side.[79] Around 500 companies with about 20,000 employees are located in the Mannheim Harbour.[80]

Air transport

Although Frankfurt International Airport is only 65 km (40 mi) to the north, at various times over the years there were daily passenger flights from Mannheim City Airport (IATA code MHG) to London, Dresden, Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, and Saarbrücken. Currently, scheduled commercial passenger flights serve Berlin and Hamburg.

Local public transport

Local public transport in Mannheim includes the RheinNeckar S-Bahn, eleven tram lines, and numerous bus lines operated by Rhein-Neckar-Verkehr (Rhine-Neckar transport) (RNV).

The RheinNeckar S-Bahn, established in 2003, connects most of the Rhine-Neckar area including lines into the Palatinate, Odenwald, and southern Hesse. All S-Bahn lines run through Mannheim Hauptbahnhof, except S5. Further S-Bahn stations are at present Mannheim-Rangierbahnhof, Mannheim-Seckenheim, and Mannheim-Friedrichsfeld-Süd.

The 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge integrated Mannheim/Ludwigshafen tramway network also extends to Heidelberg. It is operated by RNV, a company wholly owned by the three cities mentioned and a couple of municipalities in the Palatinate. RNV is the result of a merger on 1 October 2009 between the region's five former municipal transportation companies.[81] Interurban trams are operated by RNV on a triangular route between Mannheim, Heidelberg, and Weinheim that was originally established by the Upper Rhine Railway Company (Oberrheinische Eisenbahn, OEG), and the company also operates interurban trams between Bad Dürkheim, Ludwigshafen, and Mannheim. In the 1970s a proposal to build a U-Bahn out of the Mannheim and Ludwigshafen tramways was begun, but only small sections were built due to lack of funds. The only underground station in Mannheim is the Haltestelle Dalbergstraße. U-Bahn planning now has stopped. All public transport is offered at uniform prices set by the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Neckar (Rhine-Neckar transport union, VRN).

Block numbering and computer mapping

The center of the city uses an addressing system unique within Germany. Rather than street names and numbers, each block is given a code and a number is given to each building, i.e. C3, 17 is block C3, building 17. This practice dates back centuries, and is a result of the original use of the city center as a fort, with the fort's internal system being adopted when it became public streets. The street themselves are unnamed. The codes are laid out in a simple progressive pattern, i.e. C3 is between C2 and C4 in one direction and B3 and D3 in the other, but those unused to the system will often become lost. A street named Breite Straße goes through the middle of the blocks from south to north, with blocks A-K on the west side of the street and L-U on the east, with each row going 1 to at most 7 based on distance from this road. House numbers begin on the south corner nearest Breite Straße and go counterclockwise for A-K and Clockwise for L-U.[82]

This causes major issues with most mapping software, as the databases they use are based on the standard street-number system, and thus aren't able to accommodate a completely different system for a small area. A variety of fixes have been tried, none with a high level of success. In particular, these systems have issues because an address on a block can be on any of up to 4 roads, so attempts to fix the issue by giving the roads false names within the database have often failed to give accurate addressing, though such can still be seen on some platforms, like Google Maps. Finding an address in this area thus generally requires resorting to asking directions or using one of the many posted public maps.[83]

Twin towns – sister cities

- Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom (1957)

- Toulon, France (1959)

- Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf (Berlin), Germany (1961)

- Windsor, Canada (1980)

- Riesa, Germany (1988)

- Chișinău, Moldova (1989)

- Bydgoszcz, Poland (1991)

- Klaipėda, Lithuania (2002)

- Zhenjiang, China (2004)

- Haifa, Israel (2009)

- Qingdao, China (2016)

- Chernivtsi, Ukraine (2022)

Notable people

- Josepha von Heydeck (1748–1771), mistress of Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria

- Johann Baptist Cramer (1771–1858), English pianist and composer

- Friedrich Engelhorn (1821–1902), industrialist, founder of BASF

- Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840–1902), Austro-German psychiatrist

- Carl Benz (1844–1929), engine designer and automotive engineer, built the first practical motorcar

- Henry Morgenthau Sr. (1856–1946), American politician and real estate investor

- Robert Kahn (1865–1951), composer and pianist

- Otto Hermann Kahn (1867–1934), investment banker, collector and philanthropist

- Emmy Wehlen (1887–1977), musical comedy actress and silent screen star

- Sepp Herberger (1897–1977), football player and manager

- Wilhelm Fuchs (1898–1947), Nazi SS officer and Holocaust perpetrator executed for war crimes

- Hedwig Hillengaß (1902–1970), operatic soprano

- Albert Speer (1905–1981), Nazi architect, Minister for Armaments and Munitions during World War II

- Julius Hatry (1906–2000), aircraft designer and builder, created the world's first purpose-built rocket plane

- Hans Filbinger (1913–2007), politician

- Samuel Hans Adler (born 1928), German-American composer, conductor and professor

- Claus Leininger (1931–2005), theatre director and manager

- Wolf Wolfensberger (1934–2011), German-American psychologist

- Roger Fritz (1936–2021), actor

- Rudi Altig (1937–2016), cyclist

- Christiane Schmidtmer (1939–2003), actress

- Fred Breinersdorfer (born 1946), writer

- Karl W Schweizer (born 1946), historian and author

- Kurt Fleckenstein (born 1949), artist/sculptor

- Peter Dani (1956–2002), American footballer

- Norbert Schwefel (1960–2015), musician

- Juergen Adams (born 1961), ice hockey player

- Uwe Rahn (born 1962), footballer

- Christine Lambrecht (born 1965), politician (SPD)

- Franz Jung (born 1966), Roman Catholic bishop

- Steffi Graf (born 1969), tennis player

- Xavier Naidoo (born 1971), pop singer

- Christian Wörns (born 1972), footballer

- Lexi Alexander (born 1974), director

- Bülent Ceylan (born 1976), German-Turkish comedian

- Jochen Hecht (born 1977), ice hockey player

- Uwe Gensheimer (born 1989), handball player

- Giulia Enders (born 1990), writer and medical researcher

- Hakan Çalhanoğlu (born 1994), Turkish footballer

Notes and references

Notes

- in dem → im

References

- Aktuelle Wahlergebnisse, Staatsanzeiger, accessed 9 September 2021.

- "Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht am 31. Dezember 2020" [Population by nationality and sex as of December 31, 2020] (CSV). Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg (in German). June 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- "Rhine-Neckar: Rhine-Neckar in figures". 7 July 2015. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014.

- "Wörterbuchnetz - Pfälzisches Wörterbuch". woerterbuchnetz.de. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Aktuell, S. W. R. "Kurpfälzer Metropole wieder zweitgrößte Stadt im Land". swr.online (in German). Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- "Wirtschaftsstandort". www.mannheim.de. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Deutsches Havard". www.zeit.de. 23 May 2002. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Haijtema, Dominique (13 February 2005). "Auf der Suche nach einem deutschen Harvard". DIE WELT (in German). Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- "The City of Mannheim isn't Germany at its Prettiest". Foster Blog. 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- "Die 10 größten Messen in Deutschland | "Wer liefert was"". wlw.de (in German). Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Benzin im Blut: Der vergessene Mannheimer Auto-Bauer Franz Heim - Mannheim". www.rheinpfalz.de (in German). Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- "The Manhattan of Germany: the innovative Mannheim city". The New Economy. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Völklein, Marco. "200 Jahre Fahrrad - Radfahrer erobern Mannheim zurück". Süddeutsche.de (in German). Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- "Mannheim: Die Stadt der Erfindungen - Mannheim - Nachrichten und Informationen". www.mannheimer-morgen.de (in German). Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- "Stadt der Erfinder - Grünstadt". Rhein-Neckar Fernsehen (in German). 28 October 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Stadt der Erfinder: Mannheimer Augustaanlage wird zur "Allee der Innovationen" (in German), 24 October 2016, retrieved 20 December 2021

- Jan., Van Deth (2015). Demokratie in der Großstadt Ergebnisse des ersten Mannheimer Demokratie Audit. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-658-05849-4. OCLC 964356167.

- "Mannheim: Dieser Rangierbahnhof stößt an Grenzen". www.rnz.de (in German). Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- "Mannheim ist jetzt offiziell "Unesco City of Music"" (in German). RNZ. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC - Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "The rise of the smart city". The New Economy. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- "Smart City knows who needs power, and when". CNN. 19 February 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- DPA. "Slogans: "Leben im Quadrat" | svz.de". svz. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- Emmi., Brandi, Ulrike, 1957- Federhofer (2010). Ton + Technik : römische Ziegel. Limesmuseum Aalen, Zweigmuseum des Archäologischen Landesmuseums Baden-Württemberg. ISBN 978-3-8062-2403-0. OCLC 610821190.

- "Minst, Karl Josef [Transl.]: Lorscher Codex: deutsch ; Urkundenbuch der ehemaligen Fürstabtei Lorsch (Band 2): Schenkungsurkunden Nr. 167 - 818, Oberrheingau und Ladengau (Lorsch, 1968)". digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- Sonja Steiner-Welz, 400 Jahre Stadt Mannheim (Dokumente zur Stadtgeschichte). Band 1: bis zur Kaiserzeit, vol. 1, 2004, ISBN 978-3-936041-96-5, p. 41.

- "Grundriß der Stadt Mannheim im 17. Jahrhundert". www.landeskunde-online.de. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Verlegung der kurfürstlichen Residenz nach Mannheim - News - lokalmatador". www.lokalmatador.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- Boog, Horst; Rahn, Werner; Stumpf, Reinhard; Wegner, Bernd (15 November 2001). Germany and the Second World War. ISBN 978-0-19-822888-2. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939-1946 (Revised Edition, 2006), Stackpole Books.

- "Ausgabe der Klimadaten: Monatswerte". |date=July 2014 |source 2= "Dekadenrekorde".

- "Heidelberg historic weather averages". weather-online. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Mannheim - heißeste Stadt des Landes - Mannheim - Nachrichten und Informationen". www.mannheimer-morgen.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Mannheim, Germany Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- Link

- "Staatsangehörigkeiten der Ausländerinnen und Ausländer zum 31.12.2017". Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "Religionszugehörigkeit in Mannheim | Mannheim.de". www.mannheim.de. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- Fühner, Ruth (13 January 2007). "Neues in der Theaterwelt". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 17 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Championnat d'Allemagne de hockey sur glace 1979/80". www.passionhockey.com. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ""Leute sollen Spaß am Sport haben" - Bitte keine Fußball-Verhältnisse im Football". www.vereinsleben.de (in German). Retrieved 18 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Rhein-Neckar Löwen, Stuttgart und Göppingen mit Pleiten". swr.online (in German). 12 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "RAW Survivor Series Tour 2008 Ergebnisse aus Mannheim/Deutschland (5.11.08) | Wrestling-Infos.de" (in German). Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- "Dennis Siver im Schnelldurchlauf | UFC". kr.ufc.com (in Korean). 14 September 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- "FEI European Jumping Championship, Mannheim". Em2007.de. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- Express 23 June 2013

- "Rheinpfalz July 25 2008".

- Eva Gerten, dpa (27 September 2014). "Steckenpferdpolo: Trendsportart in Düsseldorf im Rheinpark". SPIEGEL ONLINE.

- (PDF). 4 February 2014 https://web.archive.org/web/20140204051309/http://www.uni-mannheim.de/1/universitaet/profil/zahlen_geschichte/statistiken/statistik/Studierendenstatistik_hws13.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Casebeer, Elizabeth. "Mannheim Elementary closes doors after 66 years: Teachers, students all attend ceremony to say goodb." U.S. Army. 14 June 2012. Retrieved on 16 November 2015.

- Montgomery, Nancy. "Closing of bases in Mannheim ends special relationship between Germans, U.S. troops." Stars and Stripes. 22 May 2011. Retrieved on 16 November 2015.

- "World's 15 Most Inventive Cities". Forbes.com. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- "Bertha Benz Memorial Route". www.bertha-benz.de. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- USAG BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG PUBLIC AFFAIRS (9 June 2011). "Mannheim Deactivation Ceremony".

- "DoDEA: Mannheim Middle School". Archived from the original on 23 September 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- "Tagesausflug Luisenpark Mannheim". Club Behinderter und ihrer Freunde Südpfalz e.V. (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "SAP-Arena". www.mannheim.citysam.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Reißinsel in Mannheim". Stadtmarketing Mannheim GmbH. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Messehostessen für die Maimarkt Messe in Mannheim" (in German). Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- "Marktplatz Mannheim". Stadtmarketing Mannheim GmbH. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Mannheimer Maimess - Themen - lokalmatador". www.lokalmatador.de (in German). Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- "TPMA | TPMA". www.tp-ma.de (in German). Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- "Arbeitslosenquote Mannheim bis 2020". Statista (in German). Retrieved 17 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim: Daten - der digitale Schatz des medizinischen Fortschritts". IHK Rhein-Neckar (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Mannheim: ABB kehrt in den Gewerbepark zurück". www.rnz.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Dietmar Hopp: Sein Bruder Rüdiger - bester Freund". www.rnz.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Alstom: Auch Mannheim vom Stellenabbau betroffen". www.rnz.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Alstom in Mannheim: Neue Standortleiterin Karin Sautter sagt "sehr positive Zukunft" voraus - Wirtschaft". www.mannheimer-morgen.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Bilfinger in Mannheim: Neues Hauptquartier symbolisiert Neuanfang". www.rnz.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Unsere Standorte im Überblick". Unilever (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Essity: Unternehmen verlagert "Tempo" nach Mannheim". www.rnz.de (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Mannheim: Phoenix-Gruppe auf stabilem Wachstumskurs" (in German). 23 September 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Mannheim: Beschäftigte von Bombardier kämpfen um Arbeitsplätze" (in German). 5 March 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Exzellenzbetrieb: Pepperl+Fuchs SE - Die Deutsche Wirtschaft" (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Siemens | Niederlassung Mannheim". Siemens Deutschland (in German). Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- "Platz 22: Mannheim - Die 25 "wertvollsten" Städte Deutschlands | Top-Ranking". finanzen.net (in German). Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- Köhler, Manfred (14 October 2021). "Bahnstreckenausbau In 29 Minuten mit dem ICE von Frankfurt nach Mannheim". FAZ.NET (in German). Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- Millenet, Jan (9 January 2019). "Mannheimer Binnenhafen ist einer der größten seiner Art". www.echo-online.de (in German). Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "Mannheim und Ludwigshafen stabil". Täglicher Hafenbericht. 31 January 2017.

- "Hafen Mannheim: Trockensommer forderte seinen Tribut". www.rnz.de (in German). Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- "Press release announcing the merger to form RNV (German-language)". 23 September 2009. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- "Mannheim, Germany - 7 Awesome Things To Do". twomonkeystravelgroup.com. 14 November 2015.

- Tom Scott (19 February 2018). "The European City Centre With No Street Names". Archived from the original on 2 November 2021 – via YouTube.

- "Partner- und Freundesstädte". mannheim.de (in German). Mannheim. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

Further reading

- Wiederkehr, Gustav: Mannheim in Sage und Geschichte, H. Haas'schen Buchdruckerei, 1907, (Festgabe zur Feier des dreihundertjährigen Bestehens der Stadt).

- David, Manfred: Mannheimer Stadtkunde. Edition Quadrat, Mannheim 1982, ISBN 3-87804-125-X.

- Staatl. Archivverwaltung Baden-Württemberg in Verbindung mit d. Städten u. d. Landkreisen Heidelberg u. Mannheim (Hrsg.): Die Stadt- und die Landkreise Heidelberg und Mannheim: Amtliche Kreisbeschreibung. Band 1: Allgemeiner Teil. Karlsruhe 1966, DNB 458203858. Band 3: Die Stadt Mannheim und die Gemeinden des Landkreises Mannheim. Karlsruhe 1970, DNB 366145509.

- Landesarchivdirektion Baden-Württemberg (Hrsg.): Das Land Baden-Württemberg – Amtliche Beschreibung nach Kreisen und Gemeinden. Band V.

- Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-17-002542-2.

- Huth, Hans: Die Kunstdenkmäler des Stadtkreises Mannheim. München 1982, ISBN 3-422-00556-0.

- Oesterreich, Carmen And Volker (Hrsg.): Mannheim, wo es am schönsten ist – 55 Lieblingsplätze. Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-936962-43-7.

- Schenk, Andreas: Mannheim und seine Bauten 1907–2007. Hrsg. v. Stadtarchiv Mannheim und Mannheimer Architektur- und Bauarchiv e. V. 5 Bde. Edition Quadrat, Mannheim 2000–2007, ISBN 3-923003-83-8.

- Walz, Guido (Red.): Der Brockhaus Mannheim. 400 Jahre Quadratestadt – Das Lexikon. Bibliographisches Institut & F. A. Brockhaus, Mannheim 2006, ISBN 3-7653-0181-7.

- Naturführer Mannheim. Entdeckungen im Quadrat. Hrsg. von der Stadt Mannheim und der Bezirksstelle für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege Karlsruhe. Verlag Regionalkultur, Ubstadt-Weiher 2000, ISBN 3-89735-132-3.

- Ellrich, Hartmut: Mannheim. Sutton, Erfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-86680-148-6.

- Nieß, Ulrich and Caroli, Michael (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Stadt Mannheim. Verlag Regionalkultur, Ubstadt-Weiher, Band 1: 2007, ISBN 978-3-89735-470-8. Band 2: 2007, ISBN 978-3-89735-471-5. Band 3: 2009, ISBN 978-3-89735-472-2.

- Mannheimer Altertumsverein/Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen: Mannheim vor der Stadtgründung – Teile I und II. Hrsg. Hansjörg Probst, 4 Bände. Mannheim 2007/08, ISBN 978-3-7917-2074-6.

- Vetter, Roland "Kein Stein soll auf dem andern bleiben" Mannheims Untergang während des Pfälzischen Erbfolgekrieges im Spiegel französischer Kriegsberichte ISBN 3-89735-204-4.