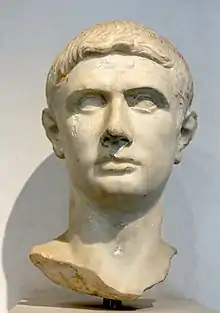

Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (/ˈbruːtəs/; Latin pronunciation: [ˈmaːrkʊs juːniʊs ˈbruːtʊs]; c. 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC), often referred to simply as Brutus, was a Roman politician, orator,[2] and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, which was retained as his legal name.[3]

Marcus Junius Brutus | |

|---|---|

Brutus on the Ides of March coin, issued shortly before his death | |

| Born | c. 85 BC[lower-alpha 1] |

| Died | 23 October 42 BC (aged 42/43) Near Philippi, Macedonia |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Other names | Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus |

| Occupation | Politician, orator and general |

| Known for | Assassination of Julius Caesar |

| Office |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Parent(s) | M. Junius Brutus and Servilia |

Early in his political career, Brutus opposed Pompey,[4] who was responsible for Brutus' father's death.[5] He also was close to Caesar. However, Caesar's attempts to evade accountability in the law courts put him at greater odds with his opponents in the Roman elite and the senate.[6] Brutus eventually came to oppose Caesar and sided with Pompey against Caesar's forces during the ensuing civil war (49–45 BC). Pompey was defeated at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48, after which Brutus surrendered to Caesar, who granted him amnesty.[7]

With Caesar's increasingly monarchical and autocratic behaviour after the civil war, several senators who later called themselves liberatores (Liberators), plotted to assassinate him. Brutus took a leading role in the assassination, which was carried out successfully on the Ides of March (15 March) of 44 BC.[8][9] In a settlement between the liberatores and the Caesarians, an amnesty was granted to the assassins while Caesar's acts were upheld for two years.[10]

Popular unrest forced Brutus and his brother-in-law, fellow assassin Gaius Cassius Longinus, to leave Rome in April 44.[11] After a complex political realignment, Octavian – Caesar's adoptive son – made himself consul and, with his colleague, passed a law retroactively making Brutus and the other conspirators murderers.[12] This led to a second civil war, in which Mark Antony and Octavian fought the liberatores led by Brutus and Cassius. The Caesarians decisively defeated the outnumbered armies of Brutus and Cassius at the two battles at Philippi in October 42.[13] After the defeat, Brutus committed suicide.[14]

His name has been condemned for betrayal of his friend and benefactor Caesar, and is perhaps only rivalled in this regard by the name of Judas Iscariot (famously in Dante's Inferno).[15] He also has been praised in various narratives, both ancient and modern, as a virtuous and committed republican who fought – however futilely – for freedom and against tyranny.[16]

Early life

Marcus Junius Brutus belonged to the illustrious plebeian gens Junia. Its semi-legendary founder was Lucius Junius Brutus, who played a pivotal role during the overthrow of Tarquinius Superbus, the last Roman king, and was afterward one of the two first consuls of the new Roman Republic in 509 BC, taking the opportunity also to have the people swear an oath never to have a king in Rome.[18]

Brutus' homonymous father was tribune of the plebs in 83 BC,[19][20] but he was killed by Pompey in 77 while serving as legate[21] in the rebellion of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.[22] He had married Servilia of the Servilii Caepiones who was the half-sister of Cato the Younger,[23] and later Julius Caesar's mistress.[24] Some ancient sources refer to the possibility of Caesar being Brutus' real father,[25] despite Caesar being only fifteen years old when Brutus was born. Ancient historians were sceptical of this possibility and "on the whole, scholars have rejected the possibility that Brutus was the love-child of Servilia and Caesar on the grounds of chronology".[26][27][28]

A relative of Brutus, Quintus Servilius Caepio, adopted him posthumously around 59 BC, and Brutus was known officially as Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, though he hardly used his legal name.[23] In 59, when Caesar was consul, Brutus also was implicated by Lucius Vettius in the Vettius affair as a member of a conspiracy plotting to assassinate Pompey in the forum.[29] Vettius was detained for admitting possession of a weapon within the city, and quickly changed this entire story, dropping Brutus' name from his accusations.[30]

Brutus' first appearance in public life was as an assistant to Cato, when the latter was appointed by the senate acting at the bequest of Publius Clodius Pulcher, as governor of Cyprus in 58.[31] According to Plutarch, Brutus was instrumental in assisting the administration of the province (specifically by converting treasure of the former king of the island into usable money); his role in administering the province, however, has "almost certainly been exaggerated".[31]

Triumvir monetalis

In 54 BC, Brutus served as triumvir monetalis, one of the three men appointed annually for producing coins, even though only another colleague is known: Quintus Pompeius Rufus. Moneyers in Brutus' day frequently issued coins commemorating their ancestors; Pompeius Rufus thus put the portraits of his two grandfathers (the dictator Sulla and Pompeius Rufus) on his denarii.[35] Brutus, like his colleague, designed a denarius with the portraits of his paternal ancestor Lucius Junius Brutus and maternal ancestor Gaius Servilius Ahala, both of whom were widely recognised in the late Republic as defenders of liberty (for, respectively, expelling the kings and killing Spurius Maelius).[36] He also made a second type featuring Libertas, the goddess of liberty, and Lucius Brutus.[32] These coins show Brutus' admiration for the tyrannicides of the early republic, already mentioned by Cicero as early as 59 BC. In addition, Brutus' denarii and their message against tyranny participated in the propaganda against Pompey and his ambitions to rule alone or become dictator.[37]

Cilicia

Brutus married Appius Claudius Pulcher's daughter Claudia, likely in 54 during Pulcher's consulship. He was elected as quaestor (and automatically enrolled in the senate) in 53.[38] Brutus then travelled with his father-in-law to Cilicia during the latter's proconsulship in the next year.[39] While in Cilicia, he spent some time as a money-lender, which was discovered two years later when Cicero was appointed proconsul between 51 and 50 BC.[40] Brutus asked Cicero to help collect two debts which Brutus had made: one to Ariobarzanes,[lower-alpha 2] the king of Cappadocia, and one to the town of Salamis.[41] Brutus' loan to Ariobarzanes was bundled with a loan also made by Pompey and both received some repayment on the debt.[41]

The loan to Salamis was more complex: officially, the loan was made by two of Brutus' friends, who requested repayment at 48 per cent per annum, which was far in excess of Cicero's previously imposed interest cap of 12 per cent. The loan dated back to 56, shortly after Brutus returned to Rome from Cyprus.[41] Salamis had sent a delegation asking to borrow money, but under the lex Gabinia it was illegal for Romans to lend to provincials in the capital, but Brutus was able to find "friends" to loan this money on his behalf, which was approved under his influence in the senate. Because the lex Gabinia also invalidated such contracts, Brutus also had his contract – officially his friends' contract – confirmed by the senate.[42] One of Brutus' friends in whose name the debt was officially issued, Marcus Scaptius, was in Cilicia during Cicero's proconsulship using force to coerce repayment, which Cicero stopped; Cicero, not seeking to endanger his friendship with Brutus, but also disappointed and angry at Brutus' mischaracterisation of the loan and the exorbitant interest rate attached,[43] was persuaded by Scaptius to defer a decision on the loan to the next governor.[42]

Opposition to Pompey

In 52, in the aftermath of the death of his uncle-in-law, Publius Clodius Pulcher (brother of his wife's father), he wrote a pamphlet, De Dictatura Pompei (On the Dictatorship of Pompey), opposing demands for Pompey to be made dictator, writing "it is better to rule no one than to be another man's slave, for one can live honourably without power but to live as a slave is impossible".[4] He was in this episode more radical than Cato the Younger, who supported Pompey's elevation as sole consul for 52, saying "any government at all is better than no government".[44] Soon after Pompey was made sole consul, Pompey passed the lex Pompeia de vi, which targeted Titus Annius Milo, for which Cicero would write a speech pro Milone.[44] Brutus also wrote for Milo, writing (a now lost) pro T Annio Milone,[lower-alpha 3] in which he connected Milo's killing of Clodius explicitly to the welfare of the state and possibly also criticising what he saw as Pompey's abuses of power.[45] This speech or pamphlet was very well received and positively viewed by later teachers of rhetoric.[46]

In the late 50s, Brutus was elected as a pontifex, one of the public priests in charge of supervising the calendar and maintaining Rome's peaceful relationship with the gods.[47] It is likely that Caesar supported his election.[47] Caesar had previously invited Brutus, after his quaestorship, to join him as a legate in Gaul, but Brutus declined, instead going with Appius Pulcher to Cilicia, possibly out of loyalty thereto.[48] During the 50s, Brutus also was involved in some major trials, working alongside famous advocates like Cicero and Quintus Hortensius. In 50, he – with Pompey and Hortensius – played a significant role in defending Brutus' father-in-law Appius Claudius from charges of treason and electoral malpractice.[49]

In the political crisis running up to Caesar's Civil War in 49, Brutus' views are mostly unknown. While he did oppose Pompey until 52, Brutus may have simply taken a tactical silence.[50]

Caesar's civil war

When Caesar's Civil War broke out in January 49 BC[7] between Pompey and Caesar, Brutus had a choice whether to support Pompey, whom the senate supported, or to join his mother's lover Caesar, who also promised vengeance for Brutus' father's death.[51] Pompey and his allies fled the city before Caesar's army arrived in March.[7] Brutus decided to support his father's killer, Pompey; this choice may have had mostly to do with Brutus' closest allies – Appius Claudius, Cato, Cicero, etc. – also all joining Pompey.[51] He did not, however, immediately join Pompey, instead travelling to Cilicia as legate for Publius Sestius before joining Pompey in winter 49 or spring 48.[52]

It is not known whether Brutus fought in the ensuing battles at Dyrrhachium and Pharsalus.[52] Plutarch says that Caesar ordered his officers to take Brutus prisoner if he gave himself up voluntarily, but to leave him alone and do him no harm if he persisted in fighting against capture.[53] After the massive Pompeian defeat at Pharsalus on 9 August 48, Brutus fled through marshland to Larissa, where he wrote to Caesar, who welcomed him graciously into his camp.[54] Plutarch also implies that Brutus told Caesar of Pompey's withdrawal plans to Egypt, but this is unlikely, as Brutus was not present when Pompey's decision to go to Egypt was made.[54]

While Caesar followed Pompey to Alexandria in 48–7, Brutus worked to effect a reconciliation between various Pompeians and Caesar.[55] He arrived back in Rome in December 47.[55] Caesar appointed Brutus as governor (likely as legatus pro praetore) for Cisalpine Gaul while he left for Africa in pursuit of Cato and Metellus Scipio.[55] After Cato's suicide following defeat at the battle of Thapsus on 6 April 46,[56] Brutus was one of Cato's eulogisers writing a pamphlet entitled Cato in which he reflected positively both on Cato's life while highlighting Caesar's clementia.[57]

After Caesar's last battle against the republican remnant in March 45, Brutus divorced his wife Claudia in June and promptly remarried his cousin Porcia, Cato's daughter, late in the same month.[58] According to Cicero the marriage caused a semi-scandal as Brutus failed to state a valid reason for his divorce from Claudia other than he wished to marry Porcia.[59] Brutus' reasons for marrying Porcia are unclear, he may have been in love or it could have been a politically motivated marriage to position Brutus as heir to Cato's supporters.[60] The marriage also caused a rift between Brutus and his mother,[60] who was resentful of the affection Brutus had for Porcia.[61]

Brutus also was promised the prestigious urban praetorship for 44 BC and possibly earmarked for the consulship in 41.[60]

Assassination of Julius Caesar

There are various different traditions describing the way in which Brutus arrived to the decision to assassinate Caesar. Plutarch, Appian, and Cassius Dio, all writing in the imperial period, focused on "pressure from [Brutus'] peers and his own philosophical conviction that awakened.... a sense of duty both to this country and to his family name".[62]

Conspiracy

By autumn 45, public opinion of Caesar was starting to sour: Plutarch, Appian, and Dio all reported graffiti glorifying Brutus' ancestor Lucius Junius Brutus, panning Caesar's kingly ambitions, and derogatory comments made to Marcus Junius Brutus in Rome's open-air courts that he was failing to live up to his ancestors.[63] Dio reports this public support came from the people of Rome; Plutarch however has the graffiti created by elites to shame Brutus into action.[64] Regardless of the specific impetus, modern historians believe that at least some portion of popular opinion had turned against Caesar by early 44.[64]

Caesar deposed two plebeian tribunes in late January 44 for removing a crown from one of his statues; this attack on the tribunes undermined one of his main arguments – defending the rights of the tribunes – for going to civil war in 49.[65] In February 44, Caesar thrice rejected a crown from Marcus Antonius to cheering crowds,[65] but later accepted the title dictator perpetuo, which in Latin translated either to dictator for life or as dictator for an undetermined term.[66]

Cicero also wrote letters asking Brutus to reconsider his association with Caesar.[67] Cassius Dio claims that Brutus' wife Porcia spurred Brutus' conspiracy, but evidence is unclear as to the extent of her influence.[68] Gaius Cassius Longinus, also one of the praetors for that year and a former legate of Caesar's,[66] also was involved in the formation of the conspiracy. Plutarch has Brutus approach Cassius at his wife's urging, while Appian and Dio have Cassius approaching Brutus (and in Dio, Cassius does so after opposing further honours for Caesar publicly).[69]

The extent of Caesar's control over the political system also stymied the ambitions of many aristocrats of Brutus' generation: Caesar's dictatorship precluded many of the avenues for success which Romans recognised. The reduction of the senate to a rubber stamp ended political discussion in Caesar's senate; there was no longer any room for anyone to shape policy except by convincing Caesar; political success became a grant of Caesar's rather than something won competitively from the people.[70] The Platonian philosophical tradition, of which Brutus was an active writer and thinker, also emphasised a duty to restore justice and to overthrow tyrants.[71]

Regardless of how the conspiracy was initially formed, Brutus and Cassius, along with Brutus' cousin and close ally of Caesar's, Decimus Junius Brutus, started to recruit to the conspiracy in late February 44.[72] They recruited men including Gaius Trebonius, Publius Servilius Casca, Servius Sulpicius Galba, and others.[73] There was a discussion late in the conspiracy as to whether Antony should be killed, which Brutus forcefully rejected: Plutarch says Brutus thought Antony could be turned to the tyrannicides; Appian says Brutus thought of the optics of purging the Caesarian elite rather than only removing a tyrant.[74]

Various plans were proposed – an ambush on the via sacra, an attack at the elections, or killing at a gladiator match – eventually, however, the conspiracy settled on a senate meeting on the Ides of March.[75] The specific date carried symbolic importance, as consuls until the mid-2nd century BC had assumed their offices on that day (instead of early January).[76] The reasons for choosing the Ides are unclear: Nicolaus of Damascus (writing in the Augustan period) assumed that a senate meeting would isolate Caesar from support; Appian reports on the possibility of other senators coming to the assassins' aid. Both possibilities "are unlikely" due to Caesar's expansion of the senate and the low number of conspirators relative to the whole senate body.[76] More likely is Dio's suggestion that a senate meeting would give the conspirators a tactical advantage as, by smuggling weapons, only the conspirators would be armed.[76]

Ides of March

The ancient sources embellish the Ides with omens ignored, soothsayers spurned, and notes to Caesar spilling the conspiracy unread, all contributing "to the tragedy of Caesar as recorded in the literature and propaganda following his death".[76] The specific implementation of the conspiracy had Trebonius detain Antony – then serving as co-consul with Caesar – outside the senate house; Caesar was then stabbed to death almost immediately.[77] The specific details of the assassination vary between authors: Nicolaus of Damascus reports some eighty conspirators, Appian only listed fifteen, the number of wounds on Caesar ranges from twenty-three to thirty-five.[78]

Plutarch reports that Caesar yielded to the attack after seeing Brutus' participation; Dio reported that Caesar shouted in Greek kai su teknon ("You too, child?").[79] Suetonius' account, however, also cites Lucius Cornelius Balbus, a friend of Caesar's, as saying that the dictator fell in silence,[77] with the possibility that Caesar spoke as a postscript.[26] As dramatic death quotes were a staple of Roman literature, the historicity of the quote is unclear. The use of kai su, however, "always has a strongly negative tone in[] other contemporary[] evidence", indicating the possibility of a curse, per classicists James Russell and Jeffrey Tatum.[80]

Immediately after Caesar's death, senators fled the chaos. None attempted to aid Caesar or to move his body. Cicero reported that Caesar fell at the foot of the statue of Pompey.[81] His body was only moved after night fell, carried home to Caesar's wife Calpurnia.[81] The conspirators travelled to the Capitoline hill; Caesar's deputy in the dictatorship, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, moved a legion of troops from the Tiber Island into the city and surrounded the forum.[82] Suetonius reports that Brutus and Cassius initially planned to seize Caesar's property and revoke his decrees, but stalled out of fear of Lepidus and Antony.[82]

Before Lepidus' troops arrived to the forum, Brutus spoke before the people in a contio. The text of that speech is lost. Dio says the liberatores promoted their support of democracy and liberty and told the people not to expect harm; Appian says the liberatores merely congratulated each other and recommended the recall of Sextus Pompey and the tribunes Caesar had recently deposed.[83] The support of the people was tepid, even though other speeches followed supporting the tyrannicide. Publius Cornelius Dolabella, who was to become consul in a few days on the 18th, decided immediately to assume the consulship illegally, expressed his support of Brutus and Cassius before the people, and joined the liberatores on hill.[84]

Cicero urged the tyrannicides to call a meeting of the senate to gather its support; Brutus however, "perhaps trusting too much in the character of Antony [or] hoping that he could win round Lepidus" who was married to one of Brutus' half-sisters, sent a delegation to the Caesarians asking for a negotiated settlement.[84] The Caesarians delayed for a day, moving troops and gathering weapons and supplies for a possible conflict.[84]

After Caesar's death, Dio reports a series of prodigies and miraculous occurrences which are "self-evidently fantastic" and likely fictitious.[85] Some of the supposed prodigies did in fact occur, but were actually unrelated to Caesar's death: Cicero's statue was knocked over but only in the next year, Mt Etna in Sicily did erupt but not contemporaneously, a comet was seen in the sky but only months later.[85]

Settlement

The initial plan from Brutus and Cassius seems to have been to establish a period of calm and then to work towards a general reconciliation.[86] While the Caesarians had troops near the capital at hand, the liberatores were soon to assume control of vast provincial holdings in the east which would provide them within the year of large armies and resources.[87] Seeing that the military situation was initially problematic, the liberatores decided then to ratify Caesar's decrees so that they could hold on to their magistracies and provincial assignments to protect themselves and rebuild the republican front.[86]

Cicero acted as an honest broker and hammered out a compromise solution: general amnesty for the assassins, ratification of Caesar's acts and appointments for the next two years, and guarantees to Caesar's veterans that they would receive their promised land grants. Caesar also was to receive a public funeral.[88] If the settlement had held, there would have been a general resumption of the republic: Decimus would go to Gaul that year and be confirmed as consul in 42, where he would then hold elections for 41.[88] The people celebrated the reconciliation but some of the hard-core Caesarians were convinced that civil war would follow.[89]

Caesar's funeral occurred on 20 March, with a rousing speech by Antony mourning the dictator and energising opposition against the tyrannicides. Various ancient sources report that the crowd set the senate house on fire and started a witch-hunt for the tyrannicides, but these may have been spurious embellishments added by Livy, according to T.P. Wiseman.[90] Contrary to what is reported by Plutarch, the assassins stayed in Rome for a few weeks after the funeral until April 44, indicating some support among the population for the tyrannicides.[91] A person calling himself Marius, claiming he was a descendant of Gaius Marius), started a plan to ambush Brutus and Cassius. Brutus, as urban praetor in charge of the city's courts, was able to get a special dispensation to leave the capital for more than 10 days, and he withdrew to one of his estates in Lanuvium, 20 miles south-east of Rome.[92] This fake Marius, for his threats to the tyrannicides (and to Antony's political base), was executed by being thrown from the Tarpeian Rock in mid- or late April.[93] Dolabella, the other consul, acting on this own initiative, took down an altar and column dedicated to Caesar.[93]

By early May, Brutus was considering exile. Octavian's arrival, along with the fake Marius, caused Antony to lose some of the support of his veterans, he responded by touring Campania – officially to settle Caesar's veterans – but actually to buttress military support.[94] Dolabella at this time was on the side of the liberatores and also was the only consul at Rome; Antony's brother Lucius Antonius helped Octavian to announce publicly that he was to fulfil the conditions of Caesar's will,[95] handing an enormous amount of wealth to the citizenry. Brutus also wrote a number of speeches disseminated to the public defending his actions, emphasising how Caesar had invaded Rome, killed prominent citizens, and suppressed the popular sovereignty of the people.[96]

By mid-May, Antony started on designs against Decimus Brutus' governorship in Cisalpine Gaul. He bypassed the senate and took the matter to the popular assemblies in June an enacted the reassignment of the Gallic province by law. At the same time, he proposed reassigning Brutus and Cassius from their provinces to instead purchase grain in Asia and Sicily.[97] There was a meeting at Brutus' house attended by Cicero, Brutus and Cassius (and wives), and Brutus' mother, in which Cassius announced his intention to go to Syria while Brutus wanted to return to Rome, but ended up going to Greece.[98] His initial plan to go to Rome, however, was to put on games in early July commemorating his ancestor Lucius Junius Brutus and promoting his cause; he instead delegated the games to a friend.[99] Octavian also held games commemorating Caesar late in the month; around this time also, the liberatores started to prepare in earnest for civil war.[100]

Liberatores' civil war

Preparations in the East

The senate assigned Brutus to Crete (and Cassius to Cyrene) in early August, both small and insignificant provinces with few troops.[102] Later in the month, Brutus left Italy for the east.[103] He was acclaimed in Greece by the younger Romans there and recruited many supporters from the young Roman aristocrats being educated in Athens.[104] He discussed with the governor of Macedonia handing the province over to him; while Antony in Rome allocated the province to his brother Gaius, Brutus travelled north with an army to Macedonia, buoyed by funds collected by two outgoing quaestores at the end of the year.[105]

In January 43, Brutus entered Macedonia and with his army, took Antony's brother Gaius captive. At the same time, the political situation in Rome turned against Antony, as Cicero was delivering his Phillipics. Over the next few months, Brutus spent his time in Greece building strength. In Italy, the senate at Cicero's urging fought against Antony at the battle of Mutina, where both consuls (Hirtius and Pansa) were killed.[105] During this time, the republicans enjoyed the support of the senate, which confirmed Brutus and Cassius' commands in Macedonia and Syria, respectively.[106][lower-alpha 4]

Dolabella switched sides in 43, killing Trebonius in Syria and raising an army against Cassius.[105] Brutus decamped for Syria in early May, writing letters to Cicero criticising Cicero's policy to support Octavian against Antony;[107] at the same time, the senate had declared Antony an enemy of the state.[108] In late May, Lepidus (married to Brutus' half-sister) – possibly forced by his own troops – joined Antony against Cicero, Octavian, and the senate, leading Brutus to write to Cicero asking him to protect both his own and Lepidus' family.[109] The next month, Brutus' wife Porcia died.[109]

Cicero's policy of attempting to unify Octavian with the senate against Antony and Lepidus started to fail in May; he requested Brutus to take his forces and march to his aid in Italy in mid-June.[110] It seems that Brutus and Cassius in the east had substantial communications delays and failed to recognise that Antony had not been defeated, contra earlier assurances after Mutina.[110][lower-alpha 5] Over the next few months from June to 19 August, Octavian marched on Rome and forced his election as consul.[111] Shortly afterwards, Octavian and his colleague, Quintus Pedius, passed the lex Pedia making the murder of a dictator retroactively illegal, and convicting Brutus and the assassins in absentia.[12] The new consuls also lifted the senate's decrees against Lepidus and Antony, clearing the way for a general Caesarian rapprochement.[112] Under that law, Decimus was killed in the west some time in autumn, defeating the republican cause in the west;[12] by 27 November 43, the Caesarians had fully settled their differences and passed the lex Titia, forming the Second Triumvirate and instituting a series of brutal proscriptions.[113] The proscriptions claimed many lives, including that of Cicero.[114]

When news of the triumvirate and their proscriptions reached Brutus in the east, he marched across the Hellespont into Macedonia to quell rebellion and conquered a number of cities in Thrace.[115] After meeting Cassius in Smyrna in January 42,[116] both generals also went on a campaign through southern Asia minor sacking cities which had aided their enemies.[117]

Brutus' depiction among certain authors, like Appian, suffered considerably from this eastern campaign: where Brutus marched into cities like Xanthus enslaving their populations and plundering their wealth.[118] Other ancient historians, including Plutarch, take a more apologetic tone, having Brutus "cry in anguish at the sufferings of his victims" a common theme used by ancient historians "to turn an otherwise condemnable action [sacking cities] into something that could be praised or even used as a positive moral example".[119] The campaign continued with less sacking but more coerced payments; the ancient tradition on this turn also is divided, with Appian seeing eastern willingness to surrender emerging from stories of Xanthus' destruction contra Cassius Dio and Plutarch viewing the later portions of the campaign as emblematic of Brutus' virtues of moderation, justice, and honour.[120]

By the end of the campaign in Asia minor, both Brutus and Cassius were tremendously rich.[121] They reconvened at Sardis and marched into Thrace in August 42.[122]

Philippi

The Caesarians also marched into Greece, evading the naval patrols of Sextus Pompey, Lucius Staius Murcus, and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus.[123] The liberatores had positioned themselves west of Neapolis with clear lines of communication back to their supplies in the east.[123] Octavian and Antony, leading the Caesarian forces, were not so lucky, as their supply lines were harassed by the superior republican fleets, leading the liberatores to adopt a strategy of attrition.[123]

Octavian and Antony had some 95,000 legionaries with 13,000 horsemen, while Brutus and Cassius had some 85,000 legionnaires and 20,000 cavalry. Flush with cash, the liberatores also had a substantial financial advantage, paying their soldiers in advance of the battle with 1,500 denarii a man and more for officers.[124] Antony moved quickly to force an engagement immediately, building a causeway under cover of darkness into the swamps that anchored the republican left flank; Cassius, commanding the republican left, countered with a wall to cut off Antony from his men and to defend his own flank.[125]

In the ensuing first Battle of Philippi, the start of the battle is unclear. Appian says Antony attacked Cassius whereas Plutarch reports battle was joined more-or-less simultaneously. [126] Brutus' forces defeated Octavian's troops on the republican right flank, sacking Octavian's camp and forcing the young Caesar to withdraw.[126] Cassius' troops fared poorly against Antony's men, forcing Cassius to withdraw to a hill. Two stories then follow: Appian reports that Cassius heard of Brutus' victory and killed himself from shame while "otherwise our sources preserve a largely unanimous account" of how one of Cassius' legates failed to convey news of Brutus' victory, leading Cassius to believe that Brutus was defeated and consequently commit suicide.[127]

Following the first battle, Brutus assumed command of Cassius' army with the promise of a substantial cash reward.[128] He also possibly promised his soldiers that he would allow them to plunder Thessalonica and Sparta after victory, as the cities had supported the triumvirs in the conflict.[129] Fearful of defections among his troops and the possibility of Antony cutting his supply lines, Brutus joined battle after attempting for some time to continue the original strategy of starving the enemy out.[130] The resulting second Battle of Philippi was a head-on-head struggle in which the sources report little tactical manoeuvres while reporting heavy casualties, especially among eminent republican families.[131]

After the defeat, Brutus fled into the nearby hills with about four legions.[132] Knowing his army had been defeated and that he would be captured, he committed suicide by falling on his sword.[14] Among his last words were, according to Plutarch, "By all means must we fly, but with our hands, not our feet".[14] Brutus reportedly also uttered the well-known verse calling down a curse quoted from Euripides' Medea: "O Zeus, do not forget who has caused all these woes".[132] It is, however, unclear whether Brutus was referring to Antony, as claimed by Appian, or otherwise Octavian, as Kathryn Tempest believes.[132] Also according to Plutarch, he praised his friends for not deserting him before encouraging them to save themselves.[14]

Some sources report that Antony, upon discovering Brutus' body, as a show of great respect, ordered Brutus' body to be wrapped in Antony's most expensive purple mantle and cremated with the ashes to be sent to Brutus' mother Servilia.[14] Suetonius, however, reports that Octavian had Brutus' head cut off and planned to have it displayed before a statue of Caesar until it was thrown overboard during a storm in the Adriatic.[133]

Chronology

- 85 BC: Brutus was born to Marcus Junius Brutus and Servilia.

- 58 BC: Served as assistant to Cato, governor of Cyprus, which helped him start his political career.[5]

- 54 BC: Marriage to Claudia (daughter of Appius Claudius Pulcher).[7]

- 53 BC: Quaestorship in Cilicia with Appius Claudius Pulcher as governor.

- 52 BC: Brutus opposes Pompey and defends Milo after Clodius' death.[7]

- 49 BC: Civil war between Pompey and Caesar starts in January. Brutus serves as legate to Publius Sestius in Cilicia, then joins Pompey in Greece in late 49.[7]

- 48 BC: Pompey loses at Pharsalus on 9 August; Brutus was pardoned by Caesar.[7]

- 46 BC: Caesar made him governor of Cisalpine Gaul; Caesar defeats Pompeian remnant at Thapsus in April.[7]

- 45 BC: Caesar appointed him urban praetor for the next year, 44.

- 44 BC: Caesar takes title of dictator perpetuo.[7] Killed Caesar with other liberatores; left Italy in late August for Athens and thence to Macedonia.[105]

- 42 BC, Jan: Successfully campaigns in southern Asia minor.[113]

- 42 BC, Sep–Oct: Battle with the triumvirs' forces and suicide.[134]

Family

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Legacy

- This was the noblest Roman of them all:

- All the conspirators save only he

- Did that they did in envy of great Caesar;

- He only, in a general honest thought

- And common good to all, made one of them.

- His life was gentle, and the elements

- So mix'd in him that Nature might stand up

- And say to all the world "This was a man!"

Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, 5.5.69–76.

Brutus' historical character has undergone numerous revisions and remains divisive. Dominant views of Brutus vary by time and geography.

Ancient views

In the ancient world, Brutus' legacy was a topic of substantial debate. Starting from his own times and shortly after his death, he was already viewed as having killed Caesar for virtuous reasons rather than envy or hatred. For example, Plutarch, in his Life of Brutus, mentions that Brutus' enemies respected him, recounting that Antony once said that "Brutus was the only man to have slain Caesar because he was driven by the splendour and nobility of the deed, while the rest conspired against the man because they hated and envied him".[135]

Even when he was still alive, Brutus' literary output, especially the pamphlets of 52 BC against Pompey's dictatorship (De dictatura Pompei) and in support of Milo (Pro T Annio Milone) coloured him as philosophically consistent: "Brutus had singled himself out as a man who acted upon an ideal code of conduct".[136] The main charge against him in the ancient world was that of ingratitude, viewing Brutus as ungrateful in taking Caesar's goodwill and support and then killing him.[137] An even more negative historiographical tradition viewed Brutus and his compatriots as criminal murderers.[138]

The divisive views of Brutus in the early Principate had little changed by the reign of Tiberius; the historian Cremutius Cordus was charged with treason for having written a history too friendly to Brutus and Cassius.[139] Around the same time, Valerius Maximus, writing with the support of the imperial regime, believed Brutus' memory suffered from "irreversible curses".[140] Of course, that the Julio-Claudio regime would have had a negative view of Brutus is expected: "admiration of Brutus and Cassius was more sinisterly interpreted as a cry of protest against the imperial system".[141] Similarly, the Forum of Augustus, which included statues of various republican heroes, omitted men such as Cato Uticensis, Cicero, Brutus, and Cassius.[142] The stoic, Seneca the Younger agreed, arguing that Brutus unjustly feared Caesar, who was a good king, and did not think through the consequences of Caesar's death.[143]

But by the time that Plutarch was actually writing his Life of Brutus, "the oral and written tradition had been worked over to create a streamlined, and largely positive, narrative of Brutus' motives".[62] Some high imperial writers also admired his rhetorical skills, especially Pliny the Younger and Tacitus, with the latter writing, "in my opinion, Brutus alone among them laid bare the convictions of his heart frankly and ingeniously, with neither ill-will nor spite".[136]

Renaissance and early modern views

Dante Alighieri's Inferno notably placed Brutus in the lowest circle of Hell for his betrayal of Caesar, where he (along with Cassius and Judas Iscariot) is personally tortured by Satan. Dante's views gave a further theological bent as well: "Brutus, Dante believed, was resisting God's 'historical design'" by killing Caesar, a "quasi-prototype for all contemporary monarchs".[15]

The moral acceptance of tyrannicide also changed. Thomas Aquinas, in On the government of princes, while accepting that tyrants should be overthrown under certain circumstances, also argued mild tyrants ought to be tolerated out of fear of unintended consequences.[144]

Renaissance writers, however, tended to view him more positively, as "it was Brutus who came to symbolise the tradition of ancient republicanism through the ages".[145] Various men in the renaissance and early modern periods were called or adopted the name Brutus: the pseudonym Stephanus Junius Brutus in 16th century France published a pamphlet Defences against tyrants; the "British Brutus" Algernon Sidney was executed for allegedly plotting against Charles II; the "Florentine Brutus", Lorenzino de' Medici, killed his cousin Duke Alessandro allegedly to free Florence.[145]

Of course, also in the early modern period is Shakespeare's depiction of Brutus in Julius Caesar, which depicts him "more of a troubled soul than a public symbol... [and] often sympathetic".[146]

Modern views

Views of Brutus as a symbol of republicanism have remained through the modern period. For example, the Anti-Federalist Papers in 1787 were written under the pseudonym "Brutus". Similar anti-federalist letters and pamphlets were written by other Roman republican names such as Cato and Poplicola.[147]

Conyers Middleton and Edward Gibbon, writing in the late 18th century, had negative views. Middleton believed Brutus' vacillations in correspondence with Cicero betrayed his claims to philosophical consistency. Gibbon conceived of Brutus' actions in terms of their results: the destruction of the republic, civil war, death, and future tyranny.[148] More teleological views of Brutus' actions are viewed sceptically by historians today: Ronald Syme, for example, pointed out "to judge Brutus because he failed is simply to judge from the results".[143]

The influential History of Rome by Theodor Mommsen in the late 19th century "cast a damning verdict on Brutus" by ending with Caesar's reforms in 46 BC, along with advancing a view that Caesar "had some sort of solution to the problem of how to deal with Rome's growing empire" (of which there is no surviving description).[149] Similarly, views of Brutus are also bound up with assessment of the republic: those who believe the republic was not worth saving or in an inevitable decline, views perhaps coloured by hindsight, view him more negatively.[149]

There remains little consensus or finality on Brutus' actions as a whole.[146]

In popular culture

- In Jonathan Swift's 1726 satire Gulliver's Travels, Gulliver arrives at the island of Glubbdubdrib and is invited by a sorcerer to visit with several historical figures brought back from the dead. Among them, Caesar and Brutus are evoked, and Caesar confesses that all his glory doesn't equal the glory Brutus gained by murdering him.

- In the Masters of Rome novels of Colleen McCullough, Brutus is portrayed as a timid intellectual whose relationship with Caesar is deeply complex. He resents Caesar for breaking his marriage arrangement with Caesar's daughter, Julia, whom Brutus deeply loved so that she could be married instead to Pompey the Great. However, Brutus enjoys Caesar's favor after he receives a pardon for fighting with Republican forces against Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus. In the lead-up to the Ides of March, Cassius and Trebonius use him as a figurehead because of his family connections to the founder of the Republic. He appears in Fortune's Favourites, Caesar's Women, Caesar and The October Horse.

- Brutus is an occasional supporting character in Asterix comics, most notably Asterix and Son in which he is the main antagonist. The character appears in the first three live Asterix film adaptations – though briefly in the first two – Asterix and Obelix vs Caesar (played by Didier Cauchy) and Asterix at the Olympic Games. In the latter film, he is portrayed as a comical villain by Belgian actor Benoît Poelvoorde: he is a central character to the film, even though he was not depicted in the original Asterix at the Olympic Games comic book. He is implied in that film to be Julius Caesar's biological son.

- In the TV series Rome, Brutus, portrayed by Tobias Menzies, is depicted as a young man torn between what he believes is right, and his loyalty to and love of a man who has been like a father to him. In the series, his personality and motives are somewhat inaccurate, as Brutus is portrayed as an unwilling participant in politics. In the earlier episodes, he is frequently inebriated and easily ruled by emotion. Brutus' relationship to Cato is not mentioned; his three sisters and wife, Porcia, are omitted.

- The Hives' song "B is for Brutus" contains titular and lyrical references to Junius Brutus.

- Red Hot Chili Peppers song "Even You Brutus?" from their 2011 album I'm with You makes reference to Brutus and Judas Iscariot.

- The video game Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood features a small side story in the form of the "Scrolls of Romulus" written by Brutus, which reveals that Caesar was a Templar, and Brutus and the conspirators were members of the Roman Brotherhood of Assassins. At the end of the side quest, the player is able to get Brutus' armour and dagger. Later at Assassin's Creed Origins, Brutus and Cassius make an appearance as Aya's earliest recruits and is the one who give the killing blow to Caesar, though his armour from Brotherhood does not make an appearance here.

See also

- Junia gens

Notes

- Cicero, Brutus, 324 says he was born ten years after the debut of Hortensius, in 95 BC, but Velleius Paterculus has Brutus aged 36 at death. Velleius's date would make Brutus too young to hold the offices he is known to have held. Tempest 2017, pp. 262–263.

- Possibly Ariobarzanes II. Cicero's time as governor overlaps with the death of Ariobarzanes II and the accession of Ariobarzanes III.

- The speech Brutus wrote for Milo is also called the exercitatio Bruti pro Milone. Balbo 2013, p. 320.

- Cicero made the proposal, "referring to Brutus by his official name",

"that as proconsul Quintus Caepio Brutus shall protect, defend, guard, and keep safe Macedonia, Illyricum, and the whole of Greece; that he will command the army which he himself has established and raised... and see to it that, together with his army, he be as close as possible to Italy".

Tempest 2017, p. 150. - "Evidently there was little understanding in the east of the effect of Lepidus' defection [by 30 May 43] and the potential crisis awaiting Rome; likewise, in the west, the problem of Dolabella [who was posing an immediate threat to Cassius and Brutus' forces] was remote and incomprehensible". Tempest 2017, p. 168.

References

Citations

- Broughton 1952, p. 576. "M. Iunius Brutus ... (53) Monetal. ca. 60 ... Q. 53 (Cilicia), Leg., Lieut. 49, 48 ?, Propr. ? or Leg., Lieut. ? Gall. Cisalp. 46–45 (early), Pr. Urb. 44, Cur. annon. 44, Procos. Crete 44, Procos. (with imperium maius) Macedonia and the East 43–42".

- Balbo 2013, p. 317.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 25, 150.

- Tempest 2017, p. 50.

- Tempest 2017, p. 238.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 58–59.

- Tempest 2017, p. 239.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 1–3.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 97–104.

- Tempest 2017, p. 241.

- Tempest 2017, p. 117.

- Tempest 2017, p. 169.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 200–208.

- Tempest 2017, p. 208.

- Tempest 2017, p. 218.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 229–30.

- Tempest 2017, Plate 3.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 17–8.

- Broughton 1952, p. 63.

- Treggiari, Susan (2019). "Adolescence and Marriage to Brutus (c. 88–78)". Servilia and her Family. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–87. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198829348.003.0004. ISBN 978-0-19-186792-7.

- Valerius Maximus (2004). Memorable deeds and sayings : one thousand tales from ancient Rome. Translated by Walker, Henry J. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. p. 205. ISBN 0-87220-675-0. OCLC 53231884.

Pompey killed Marcus Junius Brutus, a rebel legate in northern Italy, in 77 BC.

- Tempest 2017, p. 24.

- Tempest 2017, p. 25.

- Flower, Harriet (7 March 2016). "Servilia". Oxford Classical Dictionary. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.5854. ISBN 9780199381135. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Plut. Brut., 5.2.

- Tempest 2017, p. 102.

- Syme, Ronald (1960). "Bastards in the Roman Aristocracy". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 104 (3): 326. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 985248.

Chronology is against Caesar's paternity.

- Syme, Ronald (1980). "No Son for Caesar?". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 29 (4): 426. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4435732.

Caesar is excluded by plain fact

. - Tempest 2017, p. 36.

- Tempest 2017, p. 37.

- Tempest 2017, p. 40.

- Crawford 1974, p. 455.

- Tempest 2017, Plate 5.

- Tempest 2017, Plate 4.

- Crawford 1974, pp. 456, 734. Pompeius was a supporter of Pompey.

- Tempest 2017, p. 41.

- Crawford 1974, pp. 455, 456, 734, also mentioning other moneyers minting coins for and against Pompey in the 50s BC.

- Tempest 2017, p. 43.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 42–3.

- Tempest 2017, p. 45.

- Tempest 2017, p. 46.

- Tempest 2017, p. 47.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 48–49.

- Tempest 2017, p. 51.

- Tempest 2017, p. 52.

- Balbo 2013, p. 319.

- Tempest 2017, p. 53.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 43–4.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 53–4.

- Tempest 2017, p. 59.

- Tempest 2017, p. 60.

- Tempest 2017, p. 61.

- Plut. Brut., 5.1.

- Tempest 2017, p. 63.

- Tempest 2017, p. 70.

- Tempest 2017, p. 71.

- Tempest 2017, p. 74.

- Tempest 2017, p. 75.

- Cic. Att. 13.16.

- Tempest 2017, p. 76.

- Cic. Att. 13.22.

- Tempest 2017, p. 84.

- Tempest 2017, p. 86.

- Tempest 2017, p. 87.

- Tempest 2017, p. 81.

- Tempest 2017, p. 82.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 87–8.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 89–90.

- Tempest 2017, p. 91.

- Tempest 2017, p. 93.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 95–6.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 97–8.

- Tempest 2017, p. 98.

- Tempest 2017, p. 99.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 99–100.

- Tempest 2017, p. 100.

- Tempest 2017, p. 101.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 3–4.

- Tempest 2017, p. 3.

- Tempest 2017, p. 103.

- Tempest 2017, p. 107.

- Tempest 2017, p. 108.

- Tempest 2017, p. 109.

- Tempest 2017, p. 110.

- Tempest 2017, p. 106.

- Tempest 2017, p. 113.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 112–3.

- Tempest 2017, p. 114.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 114–5.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 119.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 119–20.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 116–7.

- Tempest 2017, p. 124.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 126–7.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 127.

- Tempest 2017, p. 129.

- Tempest 2017, p. 132.

- Tempest 2017, p. 133.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 134–5.

- Tempest 2017, p. 137.

- Crawford 1974, p. 518.

- Tempest 2017, p. 140.

- Tempest 2017, p. 142.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 144–146.

- Tempest 2017, p. 243.

- Tempest 2017, p. 150.

- Tempest 2017, p. 161.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 243–244.

- Tempest 2017, p. 244.

- Tempest 2017, p. 166.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 244–5.

- Tempest 2017, p. 170.

- Tempest 2017, p. 245.

- Tempest 2017, p. 171.

- Tempest 2017, p. 177.

- Tempest 2017, p. 178.

- Tempest 2017, p. 179.

- Tempest 2017, p. 182.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 183–4.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 189–191.

- Tempest 2017, p. 191.

- Tempest 2017, p. 193.

- Tempest 2017, p. 197.

- Tempest 2017, p. 198.

- Tempest 2017, p. 200.

- Tempest 2017, p. 201.

- Tempest 2017, p. 202.

- Tempest 2017, p. 203.

- Tempest 2017, p. 204.

- Tempest 2017, p. 205.

- Tempest 2017, p. 206.

- Tempest 2017, p. 207.

- Tempest 2017, p. 209.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 248–58.

- Tempest 2017, p. 211.

- Tempest 2017, p. 213.

- Tempest 2017, pp. 216–17.

- Tempest 2017, p. 175.

- Gowing 2005, p. 26.

- Gowing 2005, p. 55.

- Tempest 2017, p. 5.

- Gowing 2005, p. 145.

- Tempest 2017, p. 219.

- Tempest 2017, p. 215.

- Tempest 2017, p. 230.

- Tempest 2017, p. 231.

- Dry, Murray; Storing, Herbert J, eds. (1985). The anti-Federalist: an abridgement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77562-3. OCLC 698669562.

- Tempest 2017, p. 10.

- Tempest 2017, p. 220.

Sources

- Balbo, Andrea (2013). "Marcus Junius Brutus the orator: between philosophy and rhetoric". In Steel, Catherine; van der Blom, Henriette (eds.). Community and communication: oratory and politics in republican Rome. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964189-5.

- Broughton, Thomas Robert Shannon (1952). The magistrates of the Roman republic. Vol. 2. New York: American Philological Association.

- Crawford, Michael Hewson (1974). Roman republican coinage. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-07492-6.

- Gowing, Alain M (2005). Empire and memory: the representation of the Roman republic in imperial culture. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511610592. ISBN 0-511-12792-8. OCLC 252514679.

- Plutarch (1918) [2nd century AD]. "Life of Brutus". Parallel Lives. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 6. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. Harvard University Press. OCLC 40115288 – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Tempest, Kathryn (2017). Brutus: the noble conspirator. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18009-1.

Further reading

- Badian, Ernst (2012). "Iunius Brutus (2), Marcus". In Hornblower, Simon; et al. (eds.). The Oxford classical dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.3440. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. OCLC 959667246.

- Clarke, M. L. (1981). The noblest Roman. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Syme, Ronald (1939). The Roman revolution. Oxford University Press.

- Volk, Katharina (2018). "Review of 'Brutus: the noble conspirator'". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. ISSN 1055-7660.

- Wistrand, Erik (1981). The policy of Brutus the tyrannicide. Goteborg: Kungl.

External links

- Marcus Junius Brutus in the Digital Prosopography of the Roman Republic.

- Brutus on Livius.org

_Brutus%252C_denarius%252C_54_BC%252C_RRC_433-2.jpg.webp)

_Brutus%252C_denarius%252C_54_BC%252C_RRC_433-1.jpg.webp)