Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, whose earliest beginnings were from c. 3500 BC, with the complex urban civilization beginning around 2000 BC, and then declining from c. 1450 BC until it ended around 1100 BC, during the early Greek Dark Ages,[1] part of a wider bronze age collapse around the Mediterranean. It represents the first advanced civilization in Europe, leaving behind a number of massive building complexes, sophisticated art, and writing systems. Its economy benefited from a network of trade around much of the Mediterranean.

| |

| Geographical range | Aegean Sea, especially Crete |

|---|---|

| Period | Aegean Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 3500 BC – c. 1100 BC |

| Major sites | Capital: Knossos Other important cities: Akrotiri, Phaistos, Malia, Zakros |

| Characteristics | Advanced art, trading, agriculture and Europe's first cities |

| Preceded by | Neolithic Crete, Neolithic Greece |

| Followed by | Mycenaean Greece |

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

The civilization was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. The name "Minoan" derives from the mythical King Minos and was coined by Evans, who identified the site at Knossos with the labyrinth of the Minotaur. The Minoan civilization has been described as the earliest of its kind in Europe,[2] and historian Will Durant called the Minoans "the first link in the European chain".[3]

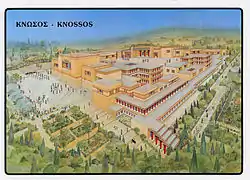

The Minoans built large and elaborate palaces up to four storeys high, featuring elaborate plumbing systems and decorated with frescoes. The largest Minoan palace is that of Knossos, followed by that of Phaistos. The function of the palaces, like most aspects of Minoan governance and religion, remains unclear. The Minoan period saw extensive trade by Crete with Aegean and Mediterranean settlements, particularly those in the Near East. Through traders and artists, Minoans cultural influence reached beyond Crete to the Cyclades, the Old Kingdom of Egypt, copper-bearing Cyprus, Canaan and the Levantine coast and Anatolia. Some of the best Minoan art was preserved in the city of Akrotiri on the island of Santorini; Akrotiri had been effectively destroyed by the Minoan eruption.

The Minoans primarily wrote in the Linear A script and also in Cretan hieroglyphs, encoding a language hypothetically labelled Minoan. The reasons for the slow decline of the Minoan civilization, beginning around 1550 BC, are unclear; theories include Mycenaean invasions from mainland Greece and the major volcanic eruption of Santorini.

Etymology

.jpg.webp)

The term "Minoan" refers to the mythical King Minos of Knossos, a figure in Greek mythology associated with Theseus, the labyrinth and the Minotaur. It is purely a modern term with a 19th-century origin. It is commonly attributed to the British archaeologist Arthur Evans,[4] who established it as the accepted term in both archaeology and popular usage. But Karl Hoeck had already used the title Das Minoische Kreta in 1825 for volume two of his Kreta; this appears to be the first known use of the word "Minoan" to mean "ancient Cretan".

Evans probably read Hoeck's book and continued using the term in his writings and findings:[5] "To this early civilization of Crete as a whole I have proposed—and the suggestion has been generally adopted by the archaeologists of this and other countries—to apply the name 'Minoan'."[6] Evans said that he applied it, not invented it.

Hoeck, with no idea that the archaeological Crete had existed, had in mind the Crete of mythology. Although Evans' 1931 claim that the term was "unminted" before he used it was called a "brazen suggestion" by Karadimas and Momigliano,[5] he coined its archaeological meaning.

Chronology and history

| 3500–2900 BC[1] | EMI | Prepalatial |

| 2900–2300 BC | EMII | |

| 2300–2100 BC | EMIII | |

| 2100–1900 BC | MMIA | |

| 1900–1800 BC | MMIB | Protopalatial (Old Palace Period) |

| 1800–1750 BC | MMIIA | |

| 1750–1700 BC | MMIIB | Neopalatial (New Palace Period) |

| 1700–1650 BC | MMIIIA | |

| 1650–1600 BC | MMIIIB | |

| 1600–1500 BC | LMIA | |

| 1500–1450 BC | LMIB | Postpalatial (at Knossos; Final Palace Period) |

| 1450–1400 BC | LMII | |

| 1400–1350 BC | LMIIIA | |

| 1350–1100 BC | LMIIIB |

Instead of dating the Minoan period, archaeologists use two systems of relative chronology. The first, created by Evans and modified by later archaeologists, is based on pottery styles and imported Egyptian artifacts (which can be correlated with the Egyptian chronology). Evans' system divides the Minoan period into three major eras: early (EM), middle (MM) and late (LM). These eras are subdivided—for example, Early Minoan I, II and III (EMI, EMII, EMIII).

Another dating system, proposed by Greek archaeologist Nikolaos Platon, is based on the development of architectural complexes known as "palaces" at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and Zakros. Platon divides the Minoan period into pre-, proto-, neo- and post-palatial sub-periods. The relationship between the systems in the table includes approximate calendar dates from Warren and Hankey (1989).

The Minoan eruption of Thera occurred during a mature phase of the LM IA period. Efforts to establish the volcanic eruption's date have been controversial. Radiocarbon dating has indicated a date in the late 17th century BC;[7][8] this conflicts with estimates by archaeologists, who synchronize the eruption with conventional Egyptian chronology for a date of 1525–1500 BC.[9][10][11] Tree-ring dating using the patterns of carbon-14 captured in the tree rings from Gordion and bristlecone pines in North America indicate an eruption date around 1560 BC.[12]

Overview

Although stone-tool evidence suggests that hominins may have reached Crete as early as 130,000 years ago, evidence for the first anatomically-modern human presence dates to 10,000–12,000 YBP.[13][14] The oldest evidence of modern human habitation on Crete is pre-ceramic Neolithic farming-community remains which date to about 7000 BC.[15] A comparative study of DNA haplogroups of modern Cretan men showed that a male founder group, from Anatolia or the Levant, is shared with the Greeks.[16] The Neolithic population lived in open villages. Fishermen's huts were found on the shores, and the fertile Messara Plain was used for agriculture.[17]

Early Minoan

The Bronze Age began on Crete around 3200 BC.[18] The Early Bronze Age (3500 to 2100 BC) has been described as indicating a "promise of greatness" in light of later developments on the island.[19] In the late third millennium BC, several locations on the island developed into centers of commerce and handiwork, enabling the upper classes to exercise leadership and expand their influence. It is possible that the original hierarchies of the local elites were replaced by monarchies, a precondition for the palaces.[20] Pottery typical of the Korakou culture was discovered in Crete from the Early Minoan Period.[21]

Middle Minoan

The palaces began to be constructed during this period of prosperity and stability, during which the Early Minoan culture turned into a "civilization". At the end of the MMII period (1700 BC) there was a large disturbance on Crete—probably an earthquake, but possibly an invasion from Anatolia.[22] The palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and Kato Zakros were destroyed.

At the beginning of the neopalatial period the population increased again,[23] the palaces were rebuilt on a larger scale and new settlements were built across the island. This period (the 17th and 16th centuries BC, MM III-Neopalatial) was the apex of Minoan civilization. After around 1700 BC, material culture on the Greek mainland reached a new high due to Minoan influence.[20]

Late Minoan

Another natural catastrophe occurred around 1600 BC, possibly an eruption of the Thera volcano. The Minoans rebuilt the palaces with several major differences in function.[24][20][25]

Around 1450 BC, Minoan culture reached a turning point due to a natural disaster (possibly an earthquake). Although another eruption of the Thera volcano has been linked to this downfall, its dating and implications are disputed. Several important palaces, in locations such as Malia, Tylissos, Phaistos and Hagia Triada, and the living quarters of Knossos were destroyed. The palace in Knossos seems to have remained largely intact, resulting in its dynasty's ability to spread its influence over large parts of Crete until it was overrun by the Mycenaean Greeks.[20]

After about a century of partial recovery, most Cretan cities and palaces declined during the 13th century BC (LHIIIB-LMIIIB). The last Linear A archives date to LMIIIA, contemporary with LHIIIA. Knossos remained an administrative center until 1200 BC. The last Minoan site was the defensive mountain site of Karfi, a refuge which had vestiges of Minoan civilization nearly into the Iron Age.[26]

Foreign influence

The influence of Minoan civilization is seen in Minoan art and artifacts on the Greek mainland. The shaft tombs of Mycenae had several Cretan imports (such as a bull's-head rhyton), which suggests a prominent role for Minoan symbolism. Connections between Egypt and Crete are prominent; Minoan ceramics are found in Egyptian cities, and the Minoans imported items (particularly papyrus) and architectural and artistic ideas from Egypt. Egyptian hieroglyphs might even have been models for the Cretan hieroglyphs, from which the Linear A and Linear B writing systems developed.[17] Archaeologist Hermann Bengtson has also found a Minoan influence in Canaanite artifacts.

Minoan palace sites were occupied by the Mycenaeans around 1420–1375 BC.[27][20] Mycenaean Greek, a form of ancient Greek, was written in Linear B, which was an adaptation of Linear A. The Mycenaeans tended to adapt (rather than supplant) Minoan culture, religion and art,[28] continuing the Minoan economic system and bureaucracy.[20]

During LMIIIA (1400–1350 BC), k-f-t-w was listed as one of the "Secret Lands of the North of Asia" at the Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III.[29] Also mentioned are Cretan cities such as Amnisos, Phaistos, Kydonia and Knossos and toponyms reconstructed as in the Cyclades or the Greek mainland. If the values of these Egyptian names are accurate, the Pharaoh did not value LMIII Knossos more than other states in the region.[30]

Geography

Crete is a mountainous island with natural harbors. There are signs of earthquake damage at many Minoan sites, and clear signs of land uplifting and submersion of coastal sites due to tectonic processes along its coast.[31]

According to Homer, Crete had 90 cities.[32] Judging by the palace sites, the island was probably divided into at least eight political units at the height of the Minoan period. The majority of Minoan sites are found in central and eastern Crete, with few in the western part of the island, especially to the south. There appear to have been four major palaces on the island: Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Kato Zakros. At least before a unification under Knossos, north-central Crete is thought to have been governed from Knossos, the south from Phaistos, the central-eastern region from Malia, the eastern tip from Kato Zakros, the west from Kydonia. Smaller palaces have been found elsewhere on the island.

Major settlements

- Knossos – the largest[33] Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete. Knossos had an estimated population of 1,300 to 2,000 in 2500 BC, 18,000 in 2000 BC, 20,000 to 100,000 in 1600 BC and 30,000 in 1360 BC.[34][35]

- Phaistos – the second-largest[33] palatial building on the island, excavated by the Italian school shortly after Knossos

- Malia – the subject of French excavations, a palatial center which provides a look into the proto-palatial period

- Kato Zakros – sea-side palatial site excavated by Greek archaeologists in the far east of the island, also known as "Zakro" in archaeological literature

- Galatas – confirmed as a palatial site during the early 1990s

- Kydonia (modern Chania), the only palatial site in West Crete

- Hagia Triada – administrative center near Phaistos which has yielded the largest number of Linear A tablets.

- Gournia – town site excavated in the first quarter of the 20th century

- Pyrgos – early Minoan site in southern Crete

- Vasiliki – early eastern Minoan site which gives its name to distinctive ceramic ware

- Fournou Korfi – southern site

- Pseira – island town with ritual sites

- Mount Juktas – the greatest Minoan peak sanctuary, associated with the palace of Knossos[36]

- Arkalochori – site of the Arkalochori Axe

- Karfi – refuge site, one of the last Minoan sites

- Akrotiri – settlement on the island of Santorini (Thera), near the site of the Thera Eruption

- Zominthos – mountainous city in the northern foothills of Mount Ida

Beyond Crete

The Minoans were traders, and their cultural contacts reached the Old Kingdom of Egypt, copper-containing Cyprus, Canaan and the Levantine coast and Anatolia. In late 2009 Minoan-style frescoes and other artifacts were discovered during excavations of the Canaanite palace at Tel Kabri, Israel, leading archaeologists to conclude that the Minoan influence was the strongest on the Canaanite city-state.[37]

Minoan techniques and ceramic styles had varying degrees of influence on Helladic Greece. Along with Santorini, Minoan settlements are found[38] at Kastri, Kythera, an island near the Greek mainland influenced by the Minoans from the mid-third millennium BC (EMII) to its Mycenaean occupation in the 13th century.[39][40][41] Minoan strata replaced a mainland-derived early Bronze Age culture, the earliest Minoan settlement outside Crete.[42]

The Cyclades were in the Minoan cultural orbit and, closer to Crete, the islands of Karpathos, Saria and Kasos also contained middle-Bronze Age (MMI-II) Minoan colonies or settlements of Minoan traders. Most were abandoned in LMI, but Karpathos recovered and continued its Minoan culture until the end of the Bronze Age.[43] Other supposed Minoan colonies, such as that hypothesized by Adolf Furtwängler on Aegina, were later dismissed by scholars.[44] However, there was a Minoan colony at Ialysos on Rhodes.[45]

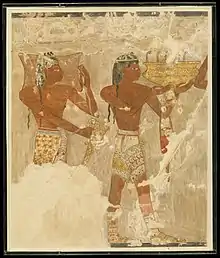

Minoan cultural influence indicates an orbit extending through the Cyclades to Egypt and Cyprus. Fifteenth-century BC paintings in Thebes, Egypt depict Minoan-appearing individuals bearing gifts. Inscriptions describing them as coming from keftiu ("islands in the middle of the sea") may refer to gift-bringing merchants or officials from Crete.[46]

Some locations on Crete indicate that the Minoans were an "outward-looking" society.[47] The neo-palatial site of Kato Zakros is located within 100 meters of the modern shoreline in a bay. Its large number of workshops and wealth of site materials indicate a possible entrepôt for trade. Such activities are seen in artistic representations of the sea, including the Ship Procession or "Flotilla" fresco in room five of the West House at Akrotiri.[48]

Agriculture and cuisine

The Minoans raised cattle, sheep, pigs and goats, and grew wheat, barley, vetch and chickpeas. They also cultivated grapes, figs and olives, grew poppies for seed and perhaps opium. The Minoans also domesticated bees.[49]

Vegetables, including lettuce, celery, asparagus and carrots, grew wild on Crete. Pear, quince, and olive trees were also native. Date palm trees and cats (for hunting) were imported from Egypt.[50] The Minoans adopted pomegranates from the Near East, but not lemons and oranges.

They may have practiced polyculture,[51] and their varied, healthy diet resulted in a population increase. Polyculture theoretically maintains soil fertility and protects against losses due to crop failure. Linear B tablets indicate the importance of orchards (figs, olives and grapes) in processing crops for "secondary products".[52] Olive oil in Cretan or Mediterranean cuisine is comparable to butter in northern European cuisine.[53] The process of fermenting wine from grapes was probably a factor of the "Palace" economies; wine would have been a trade commodity and an item of domestic consumption.[54] Farmers used wooden plows, bound with leather to wooden handles and pulled by pairs of donkeys or oxen.

Seafood was also important in Cretan cuisine. The prevalence of edible molluscs in site material[55] and artistic representations of marine fish and animals (including the distinctive Marine Style pottery, such as the LM IIIC "Octopus" stirrup jar), indicate appreciation and occasional use of fish by the economy. However, scholars believe that these resources were not as significant as grain, olives and animal produce. "Fishing was one of the major activities...but there is as yet no evidence for the way in which they organized their fishing."[56] An intensification of agricultural activity is indicated by the construction of terraces and dams at Pseira in the Late Minoan period.

Cretan cuisine included wild game: Cretans ate wild deer, wild boar and meat from livestock. Wild game is now extinct on Crete.[58] A matter of controversy is whether Minoans made use of the indigenous Cretan megafauna, which are typically thought to have been extinct considerably earlier at 10,000 BC. This is in part due to the possible presence of dwarf elephants in contemporary Egyptian art.[59]

Not all plants and flora were purely functional, and arts depict scenes of lily-gathering in green spaces. The fresco known as the Sacred Grove at Knossos depicts women facing left, flanked by trees. Some scholars have suggested that it is a harvest festival or ceremony to honor the fertility of the soil. Artistic depictions of farming scenes also appear on the Second Palace Period "Harvester Vase" (an egg-shaped rhyton) on which 27 men led by another carry bunches of sticks to beat ripe olives from the trees.[60]

The discovery of storage areas in the palace compounds has prompted debate. At the second "palace" at Phaistos, rooms on the west side of the structure have been identified as a storage area. Jars, jugs and vessels have been recovered in the area, indicating the complex's possible role as a re-distribution center for agricultural produce. At larger sites such as Knossos, there is evidence of craft specialization (workshops). The palace at Kato Zakro indicates that workshops were integrated into palace structure. The Minoan palatial system may have developed through economic intensification, where an agricultural surplus could support a population of administrators, craftsmen and religious practitioners. The number of sleeping rooms in the palaces indicates that they could have supported a sizable population which was removed from manual labor.

Tools

Tools, originally made of wood or bone, were bound to handles with leather straps. During the Bronze Age, they were made of bronze with wooden handles. Due to its round hole, the tool head would spin on the handle. The Minoans developed oval-shaped holes in their tools to fit oval-shaped handles, which prevented spinning.[49] Tools included double adzes, double- and single-bladed axes, axe-adzes, sickles and chisels.

Women

As Linear A Minoan writing has not been deciphered yet, most information available about Minoan women is from various art forms and Linear B tablets,[61] and scholarship about Minoan women remains limited.[62]

Minoan society was a divided society separating men from women in art illustration, clothing, and societal duties.[62] For example, documents written in Linear B have been found documenting Minoan families, wherein spouses and children are not all listed together.[61] In one section, fathers were listed with their sons, while mothers were listed with their daughters in a completely different section apart from the men who lived in the same household, signifying the vast gender divide present in Minoan society.[61]

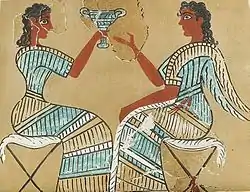

Artistically, women were portrayed very differently from men. Men were often artistically represented with dark skin while women were represented with lighter skin.[63] Minoan dress representation also clearly marks the difference between men and women. Minoan men were often depicted clad in little clothing while women's bodies, specifically later on, were more covered up. While there is evidence that the structure of women's clothing originated as a mirror to the clothing that men wore, fresco art illustrates how women's clothing evolved to be increasingly elaborate throughout the Minoan era.[64] Throughout the evolution of women's clothing, a strong emphasis was placed on the women's sexual characteristics, particularly the breasts.[63] Female clothing throughout the Minoan era emphasized the breasts by exposing cleavage or even the entire breast. Minoan women were also portrayed with "wasp" waists, similar to the modern bodice women continue to wear today.[61]

Fresco paintings portray three class levels of women; elite women, women of the masses, and servants.[61] A fourth, smaller class of women are also included among some paintings; women who participated in religious and sacred tasks.[61] Elite women were depicted in paintings as having a stature twice the size of women in lower classes, as this was a way of emphasizing the important difference between the elite wealthy women and the rest of the female population within society.[61]

Childcare was a central job for women within Minoan society.[62] Other roles outside the household that have been identified as women's duties are food gathering, food preparation, and household care-taking.[65] Additionally, it has been found that women were represented in the artisan world as ceramic and textile craftswomen.[65] As women got older it can be assumed that their job of taking care of children ended and they transitioned towards household management and job mentoring, teaching younger women the jobs that they themselves participated in.[61]

While women were often portrayed in paintings as caretakers of children, pregnant women were rarely shown in frescoes. Pregnant women were instead represented in the form of sculpted pots with the rounded base of the pots representing the pregnant belly.[61] Additionally, no Minoan art forms portray women giving birth, breast feeding, or procreating.[61] Lack of such actions leads historians to believe that these actions would have been recognized by Minoan society to be either sacred or inappropriate, and kept private within society.[61]

Childbirth was a dangerous process within Minoan society. Archeological sources have found numerous bones of pregnant women, identified by the fetus bones within their skeleton found in the abdomen area, providing strong evidence that death during pregnancy and childbirth were common features within society.[61] Further archeological finds provide evidence for female death caused by nursing as well. Death of this population is attributed to the vast amount of nutrition and fat that women lost because of lactation which they often could not get back.

Society and culture

Apart from the abundant local agriculture, the Minoans were also a mercantile people who engaged significantly in overseas trade, and at their peak may well have had a dominant position in international trade over much of the Mediterranean. After 1700 BC, their culture indicates a high degree of organization. Minoan-manufactured goods suggest a network of trade with mainland Greece (notably Mycenae), Cyprus, Syria, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia and westward as far as the Iberian peninsula. Minoan religion apparently focused on female deities, with women officiants.[66] While historians and archaeologists have long been skeptical of an outright matriarchy, the predominance of female figures in authoritative roles over male ones seems to indicate that Minoan society was matriarchal, and among the most well-supported examples known.[67][66]

The term palace economy was first used by Evans of Knossos. It is now used as a general term for ancient pre-monetary cultures where much of the economy revolved around the collection of crops and other goods by centralized government or religious institutions (the two tending to go together) for redistribution to the population. This is still accepted as an important part of the Minoan economy; all the palaces have very large amounts of space that seems to have been used for storage of agricultural produce, some remains of which have been excavated after they were buried by disasters. What role, if any, the palaces played in Minoan international trade is unknown, or how this was organized in other ways. The decipherment of Linear A would possibly shed light on this.

Government

Very little is known about the forms of Minoan government; the Minoan language has not yet been deciphered.[68] It used to be believed that the Minoans had a monarchy supported by a bureaucracy.[69] This might initially have been a number of monarchies, corresponding with the "palaces" around Crete, but later all taken over by Knossos,[70] which was itself later occupied by Mycenaean overlords. But, in notable contrast to contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, "Minoan iconography contains no pictures of recognizable kings",[66]: 175 and in recent decades it has come to be thought that before the presumed Mycenaean invasion around 1450, a group of elite families, presumably living in the "villas" and the palaces, controlled both government and religion.[71]

Saffron trade

A fresco of saffron-gatherers at Santorini is well-known. The Minoan trade in saffron, the stigma of a naturally-mutated crocus which originated in the Aegean basin, has left few material remains. According to Evans, the saffron (a sizable Minoan industry) was used for dye.[72] Other archaeologists emphasize durable trade items: ceramics, copper, tin, gold and silver.[72] The saffron may have had a religious significance.[73] The saffron trade, which predated Minoan civilization, was comparable in value to that of frankincense or black pepper.

Costume

Sheep wool was the main fibre used in textiles, and perhaps a significant export commodity. Linen from flax was probably much less common, and possibly imported from Egypt, or grown locally. There is no evidence of silk, but some use is possible.[74]

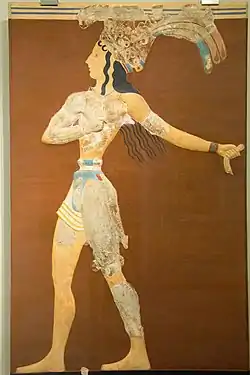

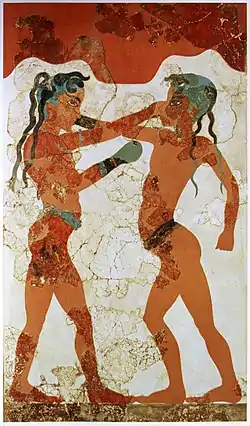

As seen in Minoan art, Minoan men wore loincloths (if poor) or robes or kilts that were often long. Women wore long dresses with short sleeves and layered, flounced skirts.[75] With both sexes, there was a great emphasis in art in a small wasp waist, often taken to improbable extremes. Both sexes are often shown with rather thick belts or girdles at the waist. Women could also wear a strapless, fitted bodice, and clothing patterns had symmetrical, geometric designs. Men are shown as clean-shaven, and male hair was short, in styles that would be common today, except for some long thin tresses at the back, perhaps for young elite males. Female hair is typically shown with long tresses falling at the back, as in the fresco fragment known as La Parisienne. This got its name because when it was found in the early 20th century, a French art historian thought it resembled Parisian women of the day.[76] Children are shown in art with shaved heads (often blue in art) except for a few very long locks; the rest of the hair is allowed to grow as they approach puberty;[77] this can be seen in the Akrotiri Boxer Fresco.

Two famous Minoan snake goddess figurines from Knossos (one illustrated below) show bodices that circle their breasts, but do not cover them at all. These striking figures have dominated the popular image of Minoan clothing, and have been copied in some "reconstructions" of largely destroyed frescos, but few images unambiguously show this costume, and the status of the figures—goddesses, priestesses, or devotees—is not at all clear. What is clear, from pieces like the Agia Triada Sarcophagus, is that Minoan women normally covered their breasts; priestesses in religious contexts may have been an exception.[78] This shows a funeral sacrifice, and some figures of both sexes are wearing aprons or skirts of animal hide, apparently left with the hair on.[79] This was probably the costume worn by both sexes by those engaged in rituals.[80]

Minoan jewellery included many gold ornaments for women's hair and also thin gold plaques to sew onto clothing.[81] Flowers were also often worn in the hair, as by the Poppy Goddess terracotta figurine and other figures. Frescos also show what are presumably woven or embroidered figures, human and animal, spaced out on clothing.[82]

Language and writing

Minoan is an unclassified language, or perhaps multiple indeterminate languages written in the same script. It has been compared inconclusively to the Indo-European and Semitic language families, as well as to the proposed Tyrsenian languages or an unclassified pre-Indo-European language family.[83][84][85][86][87] Several writing systems dating from the Minoan period have been unearthed in Crete, the majority of which are currently undeciphered.

The most well-known script is Linear A, dated to between 2500 BC and 1450 BC.[89] Linear A is the parent of the related Linear B script, which encodes the earliest known form of Greek.[90] and is also found elsewhere in the Aegean. The dating of the earliest examples of Linear B from Crete is controversial, but is unlikely to be before 1425 BC; it is assumed that the start of its use reflects conquest by Mycenae. Several attempts to translate Linear A have been made, but consensus is lacking and Linear A is currently considered undeciphered. The language encoded by Linear A is tentatively dubbed "Minoan". When the values of the symbols in Linear B are used in Linear A, they produce unintelligible words, and would make Minoan unrelated to any other known language. There is a belief that the Minoans used their written language primarily as an accounting tool and that even if deciphered, may offer little insight other than detailed descriptions of quantities.

Linear A is preceded by about a century by the Cretan hieroglyphs. It is unknown whether the language is Minoan, and its origin is debated. Although the hieroglyphs are often associated with the Egyptians, they also indicate a relationship to Mesopotamian writings.[91] They came into use about a century before Linear A, and were used at the same time as Linear A (18th century BC; MM II). The hieroglyphs disappeared during the 17th century BC (MM III).

The Phaistos Disc features a unique pictorial script. Although its origin is debated, it is now widely believed to be of Cretan origin. Because it is the only find of its kind, the script on the Phaistos disc remains undeciphered.

In addition to the above, five inscriptions dated to the 7th and 6th centuries BC have been found in Eastern Crete (and possible as late as the 3rd century BC) written in an archaic Greek alphabet that encode a clearly non-Greek language, dubbed "Eteocretan" (lit. "True Cretan"). Given the small number of inscriptions, the language remains little-known. Eteocretan inscriptions are separated from Linear A by about a millennium, and it is thus unknown if Eteocretan represents a descendant of the Minoan language.

Religion

.JPG.webp)

Arthur Evans thought the Minoans worshipped, more or less exclusively, a mother goddess, which heavily influenced views for decades. Recent scholarly opinion sees a much more diverse religious landscape although the absence of texts, or even readable relevant inscriptions, leaves the picture very cloudy. We have no names of deities until after the Mycenaean conquest. Much Minoan art is given a religious significance of some sort, but this tends to be vague, not least because Minoan government is now often seen as a theocracy, so politics and religion have a considerable overlap. The Minoan pantheon featured many deities, among which a young, spear-wielding male god is also prominent.[92] Some scholars see in the Minoan Goddess a female divine solar figure.[93][94]

It is very often difficult to distinguish between images of worshipers, priests and priestesses, rulers and deities; indeed the priestly and royal roles may have often been the same, as leading rituals is often seen as the essence of rulership. Possibly as aspects of the main, probably dominant, nature/mother goddess, archaeologists have identified a mountain goddess, worshipped at peak sanctuaries, a dove goddess, a snake goddess perhaps protectress of the household, the Potnia Theron goddess of animals, and a goddess of childbirth.[95] Late Minoan terracotta votive figures like the poppy goddess (perhaps a worshipper) carry attributes, often birds, in their diadems. The mythical creature called the Minoan Genius is somewhat threatening but perhaps a protective figure, possibly of children; it seems to largely derive from Taweret the Egyptian hybrid crocodile and hippopotamus goddess.

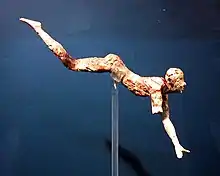

.jpg.webp)

Men with a special role as priests or priest-kings are identifiable by diagonal bands on their long robes, and carrying over their shoulder a ritual "axe-sceptre" with a rounded blade.[96] The more conventionally-shaped labrys or double-headed axe, is a very common votive offering, probably for a male god, and large examples of the Horns of Consecration symbol, probably representing bull's horns, are shown on seals decorating buildings, with a few large actual survivals. Bull-leaping, very much centred on Knossos, is agreed to have a religious significance, perhaps to do with selecting the elite. The position of the bull in it is unclear; the funeral ceremonies on the (very late) Hagia Triada sarcophagus include a bull sacrifice.[97]

According to Nanno Marinatos, "The hierarchy and relationship of gods within the pantheon is difficult to decode from the images alone." Marinatos disagrees with earlier descriptions of Minoan religion as primitive, saying that it "was the religion of a sophisticated and urbanized palatial culture with a complex social hierarchy. It was not dominated by fertility any more than any religion of the past or present has been, and it addressed gender identity, rites of passage, and death. It is reasonable to assume that both the organization and the rituals, even the mythology, resembled the religions of Near Eastern palatial civilizations."[98] It even seems that the later Greek pantheon would synthesize the Minoan female deity and Hittite goddess from the Near East.[99]

Symbolism

Minoan horn-topped altars, which Arthur Evans called Horns of Consecration, are represented in seal impressions and have been found as far afield as Cyprus. Minoan sacred symbols include the bull (and its horns of consecration), the labrys (double-headed axe), the pillar, the serpent, the sun-disc, the tree, and even the Ankh.

Haralampos V. Harissis and Anastasios V. Harissis posit a different interpretation of these symbols, saying that they were based on apiculture rather than religion.[100] A major festival was exemplified in bull-leaping, represented in the frescoes of Knossos[101] and inscribed in miniature seals.[102]

Burial practices

Similar to other Bronze Age archaeological finds, burial remains constitute much of the material and archaeological evidence for the period. By the end of the Second Palace Period, Minoan burial was dominated by two forms: circular tombs (tholoi) in southern Crete and house tombs in the north and the east. However, much Minoan mortuary practice does not conform to this pattern. Burial was more popular than cremation.[103] Individual burial was the rule, except for the Chrysolakkos complex in Malia. Here, a number of buildings form a complex in the center of Mallia's burial area and may have been the focus for burial rituals or a crypt for a notable family. Evidence of possible human sacrifice by the Minoans has been found at three sites: at Anemospilia, in a MMII building near Mt. Juktas considered a temple; an EMII sanctuary complex at Fournou Korifi in south-central Crete, and in an LMIB building known as the North House in Knossos.

Architecture

Minoan cities were connected by narrow roads paved with blocks cut with bronze saws. Streets were drained, and water and sewage facilities were available to the upper class through clay pipes.[105]

Minoan buildings often had flat, tiled roofs; plaster, wood or flagstone floors, and stood two to three stories high. Lower walls were typically constructed of stone and rubble, and the upper walls of mudbrick. Ceiling timbers held up the roofs.

Construction materials for villas and palaces varied, and included sandstone, gypsum and limestone. Building techniques also varied, with some palaces using ashlar masonry and others roughly-hewn, megalithic blocks.

In north-central Crete blue-greenschist was used as to pave floors of streets and courtyards between 1650 and 1600 BC. These rocks were likely quarried in Agia Pelagia on the north coast of central Crete.[106]

Palaces

The handful of very large structures for which Evans' term of palaces (anaktora) is still used are the best-known Minoan building types excavated on Crete; at least five have now been excavated, though that at Knossos was much larger than the others, and may always have had a unique role. The others are at: Phaistos, Zakros, Malia, Gournia, and possibly Galatas and Hagia Triada. They are monumental buildings with administrative purposes, as evidenced by large archives unearthed by archaeologists. Whether they were the actual residences of elite persons remains unclear. Each palace excavated to date has unique features, but they also share aspects which set them apart from other structures. Palaces are often multi-story, with interior and exterior staircases, lightwells, massive columns, very large storage areas and courtyards.

The first palaces were constructed at the end of the Early Minoan period in the third millennium BC at Malia. Although it was formerly believed that the foundation of the first palaces was synchronous and dated to the Middle Minoan period (around 2000 BC, the date of the first palace at Knossos), scholars now think that the palaces were built over a longer period in response to local developments. The main older palaces are Knossos, Malia and Phaistos. Elements of the Middle Minoan palaces (at Knossos, Phaistos and Malia, for example) have precedents in Early Minoan construction styles.[107] These include an indented western court and special treatment of the western façade. One example is the House on the Hill at Vasiliki, dated to the Early Minoan II period.[108] The palaces were centers of government, administrative offices, shrines, workshops and storage spaces.[109][110]

The Middle Minoan palaces are characteristically aligned with their surrounding topography. The MM palace of Phaistos appears to align with Mount Ida and Knossos is aligned with Mount Juktas,[111] both on a north–south axis. Scholars suggest that the alignment was related to the mountains' ritual significance; a number of peak sanctuaries (spaces for public ritual) have been excavated, including one at Petsofas. These sites have yielded clusters of clay figurines and evidence of animal sacrifice.

Late palaces are characterized by multi-story buildings with west facades of sandstone ashlar masonry; Knossos is the best-known example. Other building conventions included storage areas, north–south orientation, a pillar room and a western court. Architecture during the First Palace Period is identified by a square-within-a-square style; Second Palace Period construction has more internal divisions and corridors.[112] The Palace of Knossos was the largest Minoan palace. The palace is about 150 meters across and it spreads over an area of some 20,000 square meters, with its original upper levels possibly having a thousand chambers. The palace is connected to the mythological story of The Bull of Minos, since it is in this palace where it was written that the labyrinth existed. Focusing on the architectural aspects of the Palace of Knossos, it was a combination of foundations that depended on the aspects of its walls for the dimensions of the rooms, staircases, porticos, and chambers. The palace was designed in such a fashion that the structure was laid out to surround the central court of the Minoans. Aesthetically speaking, the pillars along with the stone paved northern entrance gave the palace a look and feel that was unique to the Palace of Knossos. The space surrounding the court was covered with rooms and hallways, some of which were stacked on top of the lower levels of the palace being linked through multiple ramps and staircases.[113]

Others were built into a hill, as described by the site's excavator Arthur John Evans, "...The palace of Knossos is the most extensive and occupies several hills."[114] On the east side of the court there was a grand staircase passing through the many levels of the palace, added for the royal residents. On the west side of the court, the throne room, a modest room with a ceiling some two meters high,[34] can be found along with the frescoes that were decorating the walls of the hallways and storage rooms.

Plumbing

During the Minoan Era extensive waterways were built in order to protect the growing population. This system had two primary functions, first providing and distributing water, and secondly relocating sewage and stormwater.[115] One of the defining aspects of the Minoan Era was the architectural feats of their waste management. The Minoans used technologies such as wells, cisterns, and aqueducts to manage their water supplies. Structural aspects of their buildings even played a part. Flat roofs and plentiful open courtyards were used for collecting water to be stored in cisterns.[116] Significantly, the Minoans had water treatment devices. One such device seems to have been a porous clay pipe through which water was allowed to flow until clean.

Columns

For sustaining of the roof, some higher houses, especially the palaces, used columns made usually of Cupressus sempervirens, and sometimes of stone. One of the most notable Minoan contributions to architecture is their inverted column, wider at the top than the base (unlike most Greek columns, which are wider at the bottom to give an impression of height). The columns were made of wood (not stone) and were generally painted red. Mounted on a simple stone base, they were topped with a pillow-like, round capital.[117][118]

Villas

A number of compounds known as "villas" have been excavated on Crete, mostly near palaces, especially Knossos. These structures share features of neopalatial palaces: a conspicuous western facade, storage facilities and a three-part Minoan Hall.[119] These features may indicate a similar role or that the structures were artistic imitations, suggesting that their occupants were familiar with palatial culture. The villas were often richly decorated, as evidenced by the frescos of Hagia Triada Villa A.

A common characteristic of the Minoan villas was having flat roofs. Their rooms did not have windows to the streets, the light arriving from courtyards, a common feature of larger Mediterranean in much later periods. In the 2nd millennium BC, the villas had one or two floors, and the palaces even three.

Art

_-_Heraklion_AM_-_01.jpg.webp)

Minoan art is marked by imaginative images and exceptional workmanship. Sinclair Hood described an "essential quality of the finest Minoan art, the ability to create an atmosphere of movement and life although following a set of highly formal conventions".[120] It forms part of the wider grouping of Aegean art, and in later periods came for a time to have a dominant influence over Cycladic art. Wood and textiles have decomposed, so most surviving examples of Minoan art are pottery, intricately-carved Minoan seals, palace frescos which include landscapes (but are often mostly "reconstructed"), small sculptures in various materials, jewellery, and metalwork.

The relationship of Minoan art to that of other contemporary cultures and later Ancient Greek art has been much discussed. It clearly dominated Mycenaean art and Cycladic art of the same periods,[121] even after Crete was occupied by the Mycenaeans, but only some aspects of the tradition survived the Greek Dark Ages after the collapse of Mycenaean Greece.[122]

Minoan art has a variety of subject-matter, much of it appearing across different media, although only some styles of pottery include figurative scenes. Bull-leaping appears in painting and several types of sculpture, and is thought to have had a religious significance; bull's heads are also a popular subject in terracotta and other sculptural materials. There are no figures that appear to be portraits of individuals, or are clearly royal, and the identities of religious figures is often tentative,[124] with scholars uncertain whether they are deities, clergy or devotees.[125] Equally, whether painted rooms were "shrines" or secular is far from clear; one room in Akrotiri has been argued to be a bedroom, with remains of a bed, or a shrine.[126]

Animals, including an unusual variety of marine fauna, are often depicted; the Marine Style is a type of painted palace pottery from MM III and LM IA that paints sea creatures including octopus spreading all over the vessel, and probably originated from similar frescoed scenes;[127] sometimes these appear in other media. Scenes of hunting and warfare, and horses and riders, are mostly found in later periods, in works perhaps made by Cretans for a Mycenaean market, or Mycenaean overlords of Crete.

While Minoan figures, whether human or animal, have a great sense of life and movement, they are often not very accurate, and the species is sometimes impossible to identify; by comparison with Ancient Egyptian art they are often more vivid, but less naturalistic.[128] In comparison with the art of other ancient cultures there is a high proportion of female figures, though the idea that Minoans had only goddesses and no gods is now discounted. Most human figures are in profile or in a version of the Egyptian convention with the head and legs in profile, and the torso seen frontally; but the Minoan figures exaggerate features such as slim male waists and large female breasts.[129]

What is called landscape painting is found in both frescos and on painted pots, and sometimes in other media, but most of the time this consists of plants shown fringing a scene, or dotted around within it. There is a particular visual convention where the surroundings of the main subject are laid out as though seen from above, though individual specimens are shown in profile. This accounts for the rocks being shown all round a scene, with flowers apparently growing down from the top.[130] The seascapes surrounding some scenes of fish and of boats, and in the Ship Procession miniature fresco from Akrotiri, land with a settlement as well, give a wider landscape than is usual.[131]

The largest and best collection of Minoan art is in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum ("AMH") near Knossos, on the northern coast of Crete.

Pottery

Many different styles of potted wares and techniques of production are observable throughout the history of Crete. Early Minoan ceramics were characterized by patterns of spirals, triangles, curved lines, crosses, fish bones, and beak-spouts. However, while many of the artistic motifs are similar in the Early Minoan period, there are many differences that appear in the reproduction of these techniques throughout the island which represent a variety of shifts in taste as well as in power structures.[133] There were also many small terracotta figurines.

During the Middle Minoan period, naturalistic designs (such as fish, squid, birds and lilies) were common. In the Late Minoan period, flowers and animals were still characteristic but more variety existed. However, in contrast to later Ancient Greek vase painting, paintings of human figures are extremely rare,[134] and those of land mammals not common until late periods. Shapes and ornament were often borrowed from metal tableware that has largely not survived, while painted decoration probably mostly derives from frescos.[135]

Jewelry

Minoan jewellery has mostly been recovered from graves, and until the later periods much of it consists of diadems and ornaments for women's hair, though there are also the universal types of rings, bracelets, armlets and necklaces, and many thin pieces that were sewn onto clothing. In the earlier periods gold was the main material, typically hammered very thin.[81] but later it seemed to become scarce.[136]

The Minoans created elaborate metalwork with imported gold and copper. Bead necklaces, bracelets and hair ornaments appear in the frescoes,[137] and many labrys pins survive. The Minoans mastered granulation, as indicated by the Malia Pendant, a gold pendant featuring bees on a honeycomb.[138] This was overlooked by the 19th-century looters of a royal burial site they called the "Gold Hole".[139]

Weapons

Fine decorated bronze weapons have been found in Crete, especially from LM periods, but they are far less prominent than in the remains of warrior-ruled Mycenae, where the famous shaft-grave burials contain many very richly decorated swords and daggers. In contrast spears and "slashing-knives" tend to be "severely functional".[140] Many of the decorated weapons were probably made either in Crete, or by Cretans working on the mainland.[141] Daggers are often the most lavishly decorated, with gold hilts that may be set with jewels, and the middle of the blade decorated with a variety of techniques.[142]

The most famous of these are a few inlaid with elaborate scenes in gold and silver set against a black (or now black) "niello" background, whose actual material and technique have been much discussed. These have long thin scenes running along the centre of the blade, which show the violence typical of the art of Mycenaean Greece, as well as a sophistication in both technique and figurative imagery that is startlingly original in a Greek context.

Metal vessels

Metal vessels were produced in Crete from at least as early as EM II (c. 2500 BC) in the Prepalatial period through to LM IA (c. 1450 BC) in the Postpalatial period and perhaps as late as LM IIIB/C (c. 1200 BC),[143] although it is likely that many of the vessels from these later periods were heirlooms from earlier periods.[144] The earliest were probably made exclusively from precious metals, but from the Protopalatial period (MM IB – MM IIA) they were also produced in arsenical bronze and, subsequently, tin bronze.[145] The archaeological record suggests that mostly cup-type forms were created in precious metals,[146] but the corpus of bronze vessels was diverse, including cauldrons, pans, hydrias, bowls, pitchers, basins, cups, ladles and lamps.[147] The Minoan metal vessel tradition influenced that of the Mycenaean culture on mainland Greece, and they are often regarded as the same tradition.[148] Many precious metal vessels found on mainland Greece exhibit Minoan characteristics, and it is thought that these were either imported from Crete or made on the mainland by Minoan metalsmiths working for Mycenaean patrons or by Mycenaean smiths who had trained under Minoan masters.[149]

Warfare and the "Minoan peace"

According to Arthur Evans, a "Minoan peace" (Pax Minoica) existed; there was little internal armed conflict in Minoan Crete until the Mycenaean period.[150] However, it is difficult to draw hard-and-fast conclusions from the evidence[151] and Evans' idealistic view has been questioned.[152]

No evidence has been found of a Minoan army or the Minoan domination of peoples beyond Crete; Evans believed that the Minoans had some kind of overlordship of at least parts of Mycenaean Greece in the Neopalatial Period, but it is now very widely agreed that the opposite was the case, with a Mycenaean conquest of Crete around 1450. Few signs of warfare appear in Minoan art: "Although a few archaeologists see war scenes in a few pieces of Minoan art, others interpret even these scenes as festivals, sacred dance, or sports events" (Studebaker, 2004, p. 27). Although armed warriors are depicted as stabbed in the throat with swords, the violence may be part of a ritual or blood sport.

Nanno Marinatos believes that the Neopalatial Minoans had a "powerful navy" that made them a desirable ally to have in Mediterranean power politics, at least by the 14th century as "vassals of the pharaoh", leading Cretan tribute-bearers to be depicted on Egyptian tombs such as those of the top officials Rekmire and Senmut.[153]

On mainland Greece during the shaft-grave era at Mycenae, there is little evidence for major Mycenaean fortifications; the citadels follow the destruction of nearly all neopalatial Cretan sites. Warfare by other contemporaries of the ancient Minoans, such as the Egyptians and the Hittites, is well-documented.

Skepticism and weaponry

Despite finding ruined watchtowers and fortification walls,[154] Evans said that there was little evidence of ancient Minoan fortifications. According to Stylianos Alexiou (in Kretologia 8), a number of sites (especially early and middle Minoan sites such as Aghia Photia) are built on hilltops or otherwise fortified. Lucia Nixon wrote:

We may have been over-influenced by the lack of what we might think of as solid fortifications to assess the archaeological evidence properly. As in so many other instances, we may not have been looking for evidence in the right places, and therefore we may not end with a correct assessment of the Minoans and their ability to avoid war.[155]

Chester Starr said in "Minoan Flower Lovers" that since Shang China and the Maya had unfortified centers and engaged in frontier struggles, a lack of fortifications alone does not prove that the Minoans were a peaceful civilization unparalleled in history.[156] In 1998, when Minoan archaeologists met in a Belgian conference to discuss the possibility that the Pax Minoica was outdated, evidence of Minoan war was still scanty. According to Jan Driessen, the Minoans frequently depicted "weapons" in their art in a ritual context:

The construction of fortified sites is often assumed to reflect a threat of warfare, but such fortified centres were multifunctional; they were also often the embodiment or material expression of the central places of the territories at the same time as being monuments glorifying and merging leading power.[157]

Stella Chryssoulaki's work on small outposts (or guardhouses) in eastern Crete indicates a possible defensive system; type A (high-quality) Minoan swords were found in the palaces of Mallia and Zarkos (see Sanders, AJA 65, 67, Hoeckmann, JRGZM 27, or Rehak and Younger, AJA 102). Keith Branigan estimated that 95 percent of Minoan "weapons" had hafting (hilts or handles) which would have prevented their use as such.[158] However, tests of replicas indicated that the weapons could cut flesh down to the bone (and score the bone's surface) without damaging the weapons themselves.[159] According to Paul Rehak, Minoan figure-eight shields could not have been used for fighting or hunting, since they were too cumbersome.[160] Although Cheryl Floyd concluded that Minoan "weapons" were tools used for mundane tasks such as meat processing,[161] Middle Minoan "rapiers nearly three feet in length" have been found.[162]

About Minoan warfare, Branigan concluded:

The quantity of weaponry, the impressive fortifications, and the aggressive looking long-boats all suggested an era of intensified hostilities. But on closer inspection there are grounds for thinking that all three key elements are bound up as much with status statements, display, and fashion as with aggression;... Warfare such as there was in the southern Aegean early Bronze Age was either personalized and perhaps ritualized (in Crete) or small-scale, intermittent and essentially an economic activity (in the Cyclades and the Argolid/Attica).[163]

Archaeologist Olga Krzyszkowska agreed: "The stark fact is that for the prehistoric Aegean we have no direct evidence for war and warfare per se."[164]

Collapse

Between 1935 and 1939, Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos posited the Minoan eruption theory. An eruption on the island of Thera (present-day Santorini), about 100 kilometres (62 mi) from Crete, occurred during the LM IA period (1550–1500 BC). One of the largest volcanic explosions in recorded history, it ejected about 60 to 100 cubic kilometres (14 to 24 cu mi) of material and was measured at 7 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index.[165][166][167] The eruption devastated the nearby Minoan settlement at Akrotiri on Santorini, which was entombed in a layer of pumice.[168] Although it is believed to have severely affected the Minoan culture of Crete, the extent of its effects has been debated. Early theories proposed that volcanic ash from Thera choked off plant life on the eastern half of Crete, starving the local population;[169] however, more-thorough field examinations have determined that no more than 5 millimetres (0.20 in) of ash fell anywhere on Crete.[170] Based on archaeological evidence, studies indicate that a massive tsunami generated by the Thera eruption devastated the coast of Crete and destroyed many Minoan settlements.[171][172][173] Although the LM IIIA (late Minoan) period is characterized by affluence (wealthy tombs, burials and art) and ubiquitous Knossian ceramic styles,[174] by LM IIIB (several centuries after the eruption) Knossos' wealth and importance as a regional center declined.

Significant remains have been found above the late Minoan I-era Thera ash layer, implying that the Thera eruption did not cause the immediate collapse of Minoan civilization.[175] The Minoans were a sea power, however, and the Thera eruption probably caused significant economic hardship. Whether this was enough to trigger a Minoan downfall is debated.

Many archaeologists believe that the eruption triggered a crisis, making the Minoans vulnerable to conquest by the Mycenaeans.[171] According to Sinclair Hood, the Minoans were most likely conquered by an invading force. Although the civilization's collapse was aided by the Thera eruption, its ultimate end came from conquest. Archaeological evidence suggests that the island was destroyed by fire, with the palace at Knossos receiving less damage than other sites on Crete. Since natural disasters are not selective, the uneven destruction was probably caused by invaders who would have seen the usefulness of preserving a palace like Knossos for their own use.[176] Several authors have noted evidence that Minoan civilization had exceeded its environmental carrying capacity, with archaeological recovery at Knossos indicating deforestation in the region near the civilization's later stages.[177][178]

Genetic studies

A 2013 archaeogenetics study compared skeletal mtDNA from ancient Minoan skeletons that were sealed in a cave in the Lasithi Plateau between 3,700 and 4,400 years ago to 135 samples from Greece, Anatolia, western and northern Europe, North Africa and Egypt.[179][180] The researchers found that the Minoan skeletons were genetically very similar to modern-day Europeans—and especially close to modern-day Cretans, particularly those from the Lasithi Plateau. They were also genetically similar to Neolithic Europeans, but distinct from Egyptian or Libyan populations. "We now know that the founders of the first advanced European civilization were European," said study co-author George Stamatoyannopoulos, a human geneticist at the University of Washington. "They were very similar to Neolithic Europeans and very similar to present day-Cretans."[180]

A 2017 archaeogenetics study of Minoan remains published in the journal of Nature concluded that the Minoans and the Mycenaean Greeks were genetically highly similar - but not identical - and that modern Greeks descend from these populations.[181][182] The same study also stated that at least three-quarters of the ancestral DNA of both the Minoans and the Mycenaeans came from the first Neolithic-era farmers that lived in Western Anatolia and the Aegean Sea. The remaining ancestry of the Minoans came from prehistoric populations related to those of the Caucasus and Iran, while the Mycenaean Greeks also carried this component. Unlike the Minoans however, the Mycenaeans carried a small 4-16% Bronze Age Pontic–Caspian steppe component. Whether the 'northern' ancestry in Mycenaeans was due to sporadic infiltration of Steppe-related populations in Greece, or the result of a rapid migration as in Central Europe, is not certain yet. Such a migration would support the idea that Proto-Greek speakers formed the southern wing of a steppe intrusion of Indo-European speakers. Yet, the absence of 'northern' ancestry in the Bronze Age samples from Pisidia, where Indo-European languages were attested in antiquity, casts doubt on this genetic-linguistic association, with further sampling of ancient Anatolian speakers needed.[183][184]

See also

| Library resources about Minoan civilization |

Notes

- This chronology of Minoan Crete is (with minor simplifications) the one used by Andonis Vasilakis in his book on Minoan Crete (see references), but other chronologies will vary, sometimes quite considerably (EM periods especially). Sets of different dates from other authors are set out at Minoan chronology. The adjustments made were: Source: "Early Minoan III, Middle Minoan IA 2300–1900 BCE", "Middle Minoan IIB, IIIA 1750–1650 BCE" – in both cases the run-together periods have been split equally.

- Sakoulas, Thomas. "History of Minoan Crete".

- Durant, Will (1939). "The Life of Greece". The Story of Civilization. Vol. II. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 21. ISBN 9781451647587.

- John Bennet, "Minoan civilization", Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd ed., p. 985.

- Karadimas, Nektarios; Momigliano, Nicoletta (2004). "On the Term 'Minoan' before Evans's Work in Crete (1894)" (PDF). Studi Micenei ed Egeo-anatolici. 46 (2): 243–258.

- Evans 1921, p. 1.

- Manning, Sturt W; Ramsey, CB; Kutschera, W; Higham, T; Kromer, B; Steier, P; Wild, EM (2006). "Chronology for the Aegean Late Bronze Age 1700–1400 BC". Science. 312 (5773): 565–569. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..565M. doi:10.1126/science.1125682. PMID 16645092. S2CID 21557268.

- Friedrich, Walter L; Kromer, B; Friedrich, M; Heinemeier, J; Pfeiffer, T; Talamo, S (2006). "Santorini Eruption Radiocarbon Dated to 1627–1600 B.C". Science. 312 (5773): 548. doi:10.1126/science.1125087. PMID 16645088. S2CID 35908442.

- "Chronology". Thera Foundation. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- Balter, M (2006). "New Carbon Dates Support Revised History of Ancient Mediterranean". Science. 312 (5773): 508–509. doi:10.1126/science.312.5773.508. PMID 16645054. S2CID 26804444.

- Warren PM (2006). Czerny E, Hein I, Hunger H, Melman D, Schwab A (eds.). Timelines: Studies in Honour of Manfred Bietak (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 149). Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Peeters. pp. 2: 305–321. ISBN 978-90-429-1730-9.

- Phys.org, Tree rings could pin down Thera volcano eruption date, March 30, 2020

- Wilford, J.N., "On Crete, New Evidence of Very Ancient Mariners", The New York Times, Feb 2010

- Bowner, B., "Hominids Went Out of Africa on Rafts", Wired, Jan 2010

- Broodbank, C.; Strasser, T. (1991). "Migrant farmers and the Neolithic colonisation of Crete". Antiquity. 65 (247): 233–245. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00079680. S2CID 163054761.

- R.J. King, S.S. Ozcan et al., "Differential Y-chromosome Anatolian influences on the Greek and Cretan Neolithic" Archived 2009-03-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Hermann Bengtson: Griechische Geschichte, C.H. Beck, München, 2002. 9th Edition. ISBN 340602503X. pp. 8–15

- "Ancient Greece". British Museum. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- Hermann Kinder & Werner Hilgemann, Anchor Atlas of World History, (Anchor Press: New York, 1974) p. 33.

- Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Die Griechische Frühzeit, C.H. Beck, München, 2002. ISBN 3406479855. pp. 12–18

- Rutter, Dr. Jeremy (January 2017). "The Eutresis and Korakou Cultures of Early Helladic I-II". Brewminate.

- Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black; Larry S. Krieger; Phillip C. Naylor; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 978-0-395-87274-1.

- All estimates have been revised downward by Todd Whitelaw, "Estimating the Population of Neopalatial Knossos," in G. Cadogan, E. Hatzaki, and A. Vasilakis (eds.), Knossos: Palace, City, State (British School at Athens Studies 12) (London 2004); at Moschlos in eastern Crete, the population expansion was at the end of the Neoplalatial period (Jeffrey S. Soles and Davaras, Moschlos IA 2002: Preface p. xvii).

- McEnroe, John C. (2010). Architecture of Minoan Crete: Constructing Identity in the Aegean Bronze Age. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292778399 – via Google Books.

- (Driesson, Jan, and MacDonald, Colin F. 2000)

- BBC "The Minoan Civilisation of Crete": "The later Minoan towns are in more and more inaccessible places, the last one being at Karfi, high in the Dikti Mountains. From that time onward, there are no traces of the Minoans".

- Carl Roebuck, The World of Ancient Times p. 77.

- Roebuck, p. 107.

- Kozloff, Arielle P. (2012). Amenhotep III: Egypt's Radiant Pharaoh. Cambridge University Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-139-50499-7.

- "Minos". Universidad de Salamanca. 1999 – via Google Books.

- For instance, the uplift as much as 9 metres in western Crete linked with the earthquake of 365 is discussed in L. Stathis, C. Stiros, "The 8.5+ magnitude, AD365 earthquake in Crete: Coastal uplift, topography changes, archaeological and Ihistorical signature," Quaternary International (23 May 2009).

- Homer, Odyssey xix.

- "Thera and the Aegean World III". Archived from the original on 2010-04-25. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- Castleden, Rodney (2012-10-12). The Knossos Labyrinth. ISBN 9781134967858.

- Castleden, Rodney (2002). Minoan Life in Bronze Age Crete. ISBN 9781134880645.

- Donald W. Jones (1999) Peak Sanctuaries and Sacred Caves in Minoan Crete ISBN 91-7081-153-9

- "Remains of Minoan fresco found at Tel Kabri"; "Remains Of Minoan-Style Painting Discovered During Excavations of Canaanite Palace", ScienceDaily, 7 December 2009

- Best, Jan G. P.; Vries, Nanny M. W. de (1980). Interaction and Acculturation in the Mediterranean: Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Mediterranean Pre- and Protohistory, Amsterdam, 19–23 November 1980. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-9060321942 – via Google Books.

- "The Minoans".

- Hägg and Marinatos 1984; Hardy (ed.) 1984; Broadbank 2004

- Branigan, Keith (1981). "Minoan Colonialism". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 76: 23–33. doi:10.1017/s0068245400019444. JSTOR 30103026. S2CID 246244704.

- J. N. Coldstream and G. L. Huxley, Kythera: Excavations and Studies Conducted by the University of Pennsylvania Museum and the British School at Athens (London: Faber & Faber) 1972.

- E. M. Melas, The Islands of Karpathos, Saros and Kasos in the Neolithic and Bronze Age (Studies in Mediterranean archaeology 68) (Gothenburg) 1985.

- James Penrose Harland, Prehistoric Aigina: A History of the Island in the Bronze Age, ch. V. (Paris) 1925.

- Arne Furumark, "The settlement at Ialysos and Aegean history c. 1500–1400 B.B.", in Opuscula archaeologica 6 (Lund) 1950; T. Marketou, "New Evidence on the Topography and Site History of Prehistoric Ialysos." in Soren Dietz and Ioannis Papachristodoulou (eds.), Archaeology in the Dodecanese (1988:28–31).

- Dickinson, O (1994) p. 248

- Hoffman, Gail L. (1997). Imports and Immigrants: Near Eastern Contacts with Iron Age Crete. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472107704 – via Google Books.

- Warren, Peter (1979). "The Miniature Fresco from the West House at Akrotiri, Thera, and Its Aegean Setting". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 99: 115–129. doi:10.2307/630636. ISSN 0075-4269. JSTOR 630636. S2CID 161908616.

- Hood, Sinclair (1971) "The Minoans; the story of Bronze Age Crete"

- Hood (1971), 87

- However, Hamilakis raised doubts in 2007 that systematic polyculture was practiced on Crete. (Hamilakis, Y. (2007) Wiley.com

- Sherratt, A. (1981) Plough and Pastoralism: Aspects of the Secondary Products Revolution

- Hood (1971), 86

- Hamilakis, Y (1999) Food Technologies/Technologies of the Body: The Social Context of Wine and Oil Production and Consumption in Bronze Age Crete

- Dickinson, O (1994) The Aegean Bronze Age p. 28)

- Castleden, Rodney (2002). Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete. ISBN 9781134880645.

- Hood (1978), 145–146; German, Senta, "The Harvester Vase", Khan Academy

- Hood (1971), 83

- Marco Masseti, Atlas of terrestrial mammals of the Ionian and Aegean islands, Walter de Gruyter, 30/10/2012

- Hood (1978), 145-146; Honour and Fleming, 55-56; "The Harvester Vase", German, Senta, Khan Academy

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn (2016-08-12). Budin, Stephanie Lynn; Turfa, Jean Macintosh (eds.). Women in Antiquity. doi:10.4324/9781315621425. ISBN 9781315621425.

- Olsen, Barbara A. (February 1998). "Women, children and the family in the Late Aegean Bronze Age: Differences in Minoan and Mycenaean constructions of gender". World Archaeology. 29 (3): 380–392. doi:10.1080/00438243.1998.9980386. ISSN 0043-8243.

- Lee, Mireille M. (2000), "9. Deciphering Gender in Minoan Dress", in Rautman, Alison E (ed.), Reading the Body, University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 111–123, doi:10.9783/9781512806830-011, ISBN 9781512806830

- Myres, John L. (January 1950). "1. Minoan Dress". Man. 50: 1–6. doi:10.2307/2792547. JSTOR 2792547.

- Nikolaïdou, Marianna (2012), "Looking for Minoan and Mycenaean Women", A Companion to Women in the Ancient World, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 38–53, doi:10.1002/9781444355024.ch3, ISBN 9781444355024

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn (2004). The Ancient Greeks: New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 175–189. ISBN 1-57607-815-9. OCLC 57247347.

- "Art, religious artifacts support idea of Minoan matriarchy on ancient Crete, researcher says". The University of Kansas. 2017-06-09. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Trounson, Andrew (2019-11-05). "How do you crack the code to a lost ancient script?". University of Melbourne. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- "Greece: Secrets of the Past - The Minoans". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2020-12-31.

- Honour and Fleming, 52

- Chapin, 60-61

- "Classical Views". Classical Association of Canada. 2000 – via Google Books.

- Nilsson, Martin Persson (1950). The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. ISBN 9780819602732 – via Google Books.

- Castleden, 11

- "Minoan Dress".

- "Minoan woman or goddess from the palace of Knossos ("La Parisienne")" by Senta German, Khan Academy

- Marinatos (1993), p. 202

- Castleden, 7

- "Snake Goddess" by Senta German, Khan Academy

- Marinatos (2010), 43-44

- Hood (1978), 188-190

- Hood (1978), 62

- Stephanie Lynn Budin; John M. Weeks (2004). The Ancient Greeks: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 26. ISBN 9781576078143. OCLC 249196051. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Facchetti & Negri 2003.

- Yatsemirsky 2011.

- Beekes 2014, p. 1.

- Brown 1985, p. 289.

- Haarmann 2008, pp. 12–46.

- John Chadwick (2014). The Decipherment of Linear B. Cambridge University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-107-69176-6.

- Hood (1971), 111

- Sarah Iles Johnston (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Harvard University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- Evidence of Minoan Astronomy and Calendrical Practises

- Marinatos, Nanno. Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess: A Near Eastern Koine (2013).

- Kristiansen, Kristiansen & Larsson, 84-86

- Kristiansen, Kristiansen & Larsson, 85

- "Hagia Triada sarcophagus", German, Senta, Khan Academy

- Nanno Marinatos (2004). "Minoan and Mycenaean Civilizations". In Sarah Isles Johnston (ed.). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Harvard University Press. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-0674015173.

- Sailors, Cara. "The Function of Mythology and Religion in Ancient Greek Society." East Tennessee State University, Digital Commons, 2008, dc.etsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3471&context=etd.

- Harissis, Haralampos V.; Harissis, Anastasios V. (2009). Apiculture in the Prehistoric Aegean: Minoan and Mycenaean Symbols Revisited. British Archaeological Reports (S1958). ISBN 978-1-4073-0454-0.

- In the small courtyard of the east wing of the palace of Knossos.

- An ivory figure reproduced by Spyridon Marinatos and Max Hirmer, Crete and Mycenae (New York) 1960, fig. 97, also shows the bull dance.

- Hood (1971), 140

- B.P. Mihailov; S.B. Bezsonov; B.D. Blavatski; S.A. Kaufman; I.L. Matsa; A.M. Pribâtkova; M.I. Rzianin; I.I. Savitski; A.G. Tsires; E.G. Cernov; I.S. Iaralov (1961). Istoria Generală a Arhitecturii (in Romanian). Editura Tehnică. p. 88.

- Ian Douglas, Cities: An Environmental History, p. 16, I.B. Tauris: London and New York (2013)

- Tziligkaki, Eleni K. (2010). "Types of schist used in buildings of Minoan Crete" (PDF). Hellenic Journal of Geosciences. 45: 317–322. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- D. Preziosi and L.A. Hitchcock Aegean Art and Architecture pp. 48–49, Oxford University Press (1999)

- Dudley J. Moore (2015). In Search of the Classical World: An Introduction to the Ancient Aegean. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4438-8145-6.

- Demetrios Protopsaltis (2012). An Encyclopedic Chronology of Greece and Its History. Xlibris Corporation. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4691-3999-9.

- Marvin Perry (2012). Western Civilization: A Brief History, Volume I: To 1789. Cengage Learning. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-133-71418-7.

- Preziosi, D. & Hitchcock, L.A. (1999) p. 86

- Preziosi, D. & Hitchcock, L.A. (1999) p. 121

- Scarre, Christopher; Stefoff, Rebecca (2003). "4, Knossos Today". The Palace of Minos at Knossos. New York: Oxford University. ISBN 978-0195142723.

- Castleden, Rodney (1990). The Knossos Labyrinth: A New View of the 'Palace of Minos' at Knossos. London: Routledge.

- J.B, Rose; A.N, Angelakis (2014). Evolution of Sanitation and Wastewater Technologies through the Centuries. London: IWA Publishing. p. 2.

- J.B, Rose; A.N, Angelakis (2014). Evolution of Sanitation and Wastewater Technologies Through the Centuries. London: IWA Publishing. p. 5.

- Benton and DiYanni 1998, p. 67.

- Bourbon 1998, p 34

- Letesson, Quentin (January 2013). "Minoan Halls: A Syntactical Genealogy". American Journal of Archaeology. 117 (3): 303–351. doi:10.3764/aja.117.3.0303. S2CID 191259609. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Hood (1978), 56

- Hood (1978), 17-18, 23-23

- Hood (1978), 240-241

- Honour & Fleming, 53

- Gates (2004), 33-34, 41

- e.g. Hood (1978), 53, 55, 58, 110

- Chapin, 49-51

- Hood (1978), 37-38

- Hood (1978), 56, 233-235

- Hood (1978), 235-236

- Hood (1978), 49-50, 235-236; Chapin, 47 and throughout

- Hood (1978), 63-64

- German, Senta, "Octopus vase" Khan Academy

- Castleden, Rodney (1993). Minoans: Life in Bronze Age. Routledge. p. 106.

- Hood (1978), 34, 42, 43

- Hood (1978), 27

- Hood (1978), 205-206

- "Greek Jewelry – AJU".

- Nelson, E Charles; Mavrofridis, Georgios; Anagnostopoulos, Ioannis Th (2020-09-30). "Natural History of a Bronze Age Jewel Found in Crete: The Malia Pendant". The Antiquaries Journal. 101: 67–78. doi:10.1017/S0003581520000475. ISSN 0003-5815. S2CID 224985281.

- Hood (1978), 194-195

- Hood (1978), 173-175, 175 quoted

- Hood (1978), 175

- Hood (1978), 176-177

- Hemingway, Séan (1 January 1996). "Minoan Metalworking in the Postpalatial Period: A Deposit of Metallurgical Debris from Palaikastro". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 91: 213–252. doi:10.1017/s0068245400016488. JSTOR 30102549. S2CID 127346339.

- Rehak, Paul (1997). "Aegean Art Before and After the LM IB Cretan Destructions". In Laffineur, Robert; Betancourt, Philip P. (eds.). TEXNH. Craftsmen, Craftswomen and Craftsmanship in the Aegean Bronze Age / Artisanat et artisans en Égée à l'âge du Bronze: Proceedings of the 6th International Aegean Conference / 6e Rencontre égéenne internationale, Philadelphia, Temple University, 18–21 April 1996. Liège: Université de Liège, Histoire de l'art et archéologie de la Grèce antique. p. 145. ISBN 9781935488118.

- Clarke, Christina F. (2013). The Manufacture of Minoan Metal Vessels: Theory and Practice. Uppsala: Åströms Förlag. p. 1. ISBN 978-91-7081-249-1.

- Davis 1977

- Matthäus, Hartmut (1980). Die Bronzegefässe der kretisch-mykenischen Kultur. München: C.H. Beck. ISBN 9783406040023.

- Catling, Hector W. (1964). Cypriot Bronzework in the Mycenaean World. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 187.

- Davis 1977, pp. 328–352

- Niemeier, W.-B. "Mycenaean Knossos and the Age of Linear B". Studi Micenei ed Egeoanatolici. 1982: 275.

- "Pax Minoica in Aegean". News – ekathimerini.com.

- Alexiou wrote of fortifications and acropolises in Minoan Crete, in Kretologia 8 (1979), pp. 41–56, and especially in C.G. Starr, "Minoan flower-lovers" in The Minoan Thalassocracy: Myth and Reality R. Hägg and N. Marinatos, eds. (Stockholm) 1994, pp. 9–12.

- Marinatos (2010), 4-5

- Gere, Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism

- Nixon 1983.

- Starr, Chester (1984). Robin Hägg, Nanno Marinatos (ed.). The Minoan Thalassocracy. Skrifter utgivna av Svenska institutet i Athen, 4o. Vol. 32. Stockholm: Svenska institutet i Athen. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-91-85086-78-8.

- Driessen 1999.

- Branigan 1999, pp. 87–94.

- D'Amato, Raffaele; Salimbeti, Andrea (2013). Early Aegean Warrior 5000–1450 BC. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-860-5.

- Rehak 1999.

- Floyd 1999.

- Hood (1971)

- Branigan 1999, p. 92.

- Krzyszkowska 1999.

- "Santorini eruption much larger than originally believed". 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-10.