Mycobacterium leprae

Mycobacterium leprae (also known as the leprosy bacillus or Hansen's bacillus), is a bacterium that causes Hansen’s disease (leprosy), which is a chronic, curable infectious disease that damages the peripheral nerves and targets the skin, eyes, nose, and muscles.[1] It was discovered in 1873 by the Norwegian physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen, and was the first bacterium to be identified as causing disease in humans.[2] M. Leprae is an acid-fast rod shaped bacterium and an obligate intracellular parasite, which means, unlike its relative Mycobacterium tuberculosis, it cannot be grown in cell-free laboratory media.

| Mycobacterium leprae | |

|---|---|

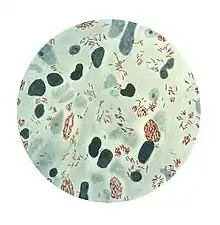

| |

| Microphotograph of Mycobacterium leprae taken from a skin lesion. The small brick-red rod-shaped cells appear in clusters. Source: CDC | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Actinomycetota |

| Class: | Actinomycetia |

| Order: | Mycobacteriales |

| Family: | Mycobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Mycobacterium |

| Species: | M. leprae |

| Binomial name | |

| Mycobacterium leprae Hansen, 1874 | |

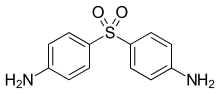

Mycobacterium leprae was sensitive to dapsone but resistance against this antibiotic began to develop in the 1960s. Currently, a multidrug treatment (MDT) is recommended by the World Health Organization, including dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine.

Microbiology

_Wade_Fite_stain.jpg.webp)

M. leprae is an intracellular, pleomorphic, acid-fast, pathogenic bacterium.[3] It is an aerobic bacillus (rod-shaped bacterium) with parallel sides and round ends, surrounded by the characteristic waxy coating unique to mycobacteria. In size and shape, it closely resembles Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This bacterium often occurs in large numbers within the lesions of lepromatous leprosy that are usually grouped together like bundles of cigars or arranged in a palisade.[4] Due to its thick waxy coating, M. leprae is stained with a carbol fuchsin rather than with the traditional Gram stain. Detail understanding of cell wall/cell envelope gives the insights of for molecular basis for leprosy pathogenesis.[5] Optical microscopy demonstrate that M. leprae can, in host cells, be found singly or in clumps referred to as "globi", the bacilli can be straight or slightly curved, with a length ranging from 1–8 μm and a diameter of 0.3 μm. [6][7][8]

Cultivation

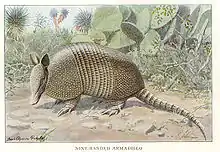

Efforts to culture the bacteria in vivo are still unsuccessful.[9]Because the organism is an obligate intracellular parasite, it lacks many necessary genes for independent survival, causing difficulty in culturing the organism. The complex and unique cell wall that makes members of the genus Mycobacterium difficult to destroy is also the reason for the extremely slow replication rate. Virulence factors include a waxy exterior coating, formed by the production of mycolic acids unique to Mycobacterium. Since in vitro cultivation is not generally possible, it has instead been grown in mouse foot pads and more recently in nine-banded armadillos because they, like humans, are susceptible to leprosy. Armadillos have a much lower body temperature than most mammals, allowing the bacterium to typically grow in their lungs, liver, and spleen.[10]

Genome

Mycobacterium leprae has the unique properties among other microbes, such as its lengthy doubling time (ranging from 12-14 days), as well as its inability to be cultured in the laboratory.[11][12] Comparing the genome sequence of M. leprae with that of M. tuberculosis provides clear explanations for these properties, and reveals an extreme case of reductive evolution. Less than half of the genome contains functional genes. Gene deletion and decay appear to have eliminated many important metabolic activities, including siderophore production, part of the oxidative and most of the microaerophilic and anaerobic respiratory chains, and numerous catabolic systems and their regulatory circuits.[13] This reductive evolution is largely linked to the organism's development into an obligate intracellular microbe.[14]

The first genome sequence of a strain of M. leprae was completed in 2001, which revealed only half of the genome contains protein-coding regions and the other half consists of pseudogens and non-coding regions.[15] The genome sequence of a strain originally isolated in Tamil Nadu, India, and designated TN, was completed in 2013. The sequence was obtained by a combined approach, employing automated DNA sequence analysis of selected cosmids and whole-genome 'shotgun' clones. After the finishing process, the genome sequence was found to contain 3,268,203 base pairs (bp), and to have an average G+C content of 57.8%, values much lower than the corresponding values for M. tuberculosis, which are 4,441,529 bp and 65.6% G+C.[16]

Evolution and pseudogenes

Mycobacterium leprae has undergone a dramatic reduction in genome size with the loss of many genes. This genome reduction is not complete and numerous genes are still present as nonfunctional pseudogenes. Downsizing from a genome of 4.42 Mbp, such as that of M. tuberculosis, to one of 3.27 Mbp would account for the loss of some 1200 protein-coding sequences. Some evidence shows that many of the genes that were present in the genome of the common ancestor of M. leprae and M. tuberculosis have been lost in the M. leprae genome.[15] 1500 genes are still common to both M. leprae and M. tuberculosis.

Ancient Mycobacterium leprae

Almost complete sequences of M. leprae from medieval skeletons with osteological lesions suggestive of leprosy from different Europe geographic origins were obtained using DNA capture techniques and high-throughput sequencing. Ancient sequences were compared with those of modern strains from biopsies of leprosy patients representing diverse genotypes and geographic origins, giving new insights in the understanding of its evolution and course through history, phylogeography of the leprosy bacillus, and the disappearance of leprosy from Europe.

Verena J. Schuenemann et al. demonstrated a remarkable genomic conservation during the past 1000 years and a close similarity between modern and ancient strains, suggesting that the sudden decline of leprosy in Europe was not due to a loss of virulence, but due to extraneous factors, such as other infectious diseases, changes in host immunity, or improved social conditions.[17]

The geographic occurrences of M. leprae include: Angola, Brazil, Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Federated States of Micronesia, India, Kiribati, Madagascar, Nepal, Republic of Marshall Islands, and the United Republic of Tanzania.[18]

Evolution

The closest relative to M. leprae is M. lepromatosis.[19] These species diverged 13.9 million years ago (95% highest posterior density 8.2 million years ago – 21.4 million years ago ) The most recent common ancestor of the extant M. leprae strains was calculated to have lived 3,607 years ago [95% highest posterior density 2204–5525 years ago]. The estimated substitution rate was 7.67 x 10−9 substitutions per site per year, similar to other bacteria.

A study of genomes isolated from medieval cases estimated the mutation rate to be 6.13 × 10−9.[20] The authors also showed that the leprosy bacillus in the Americas was brought there from Europe.

The ancestors of M. leprae and M. tuberculosis have been estimated to have separated 36 million years ago.[21]

Another study suggests that M. leprae originated in East Africa and spread from there to Europe and the Middle East initially before spreading to West Africa and the Americas in the last 500 years.[22]

Epidemiology

The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that, globally, around 128,000 new leprosy cases were detected in 2020. [23]

Pathogenesis

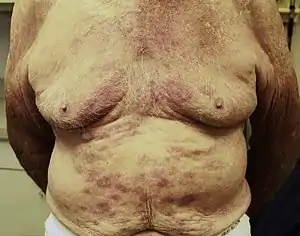

The incubation period of M. leprae can range between 9 months and 20 years.[24] It replicates intracellularly inside histiocytes and nerve cells and has two forms. One form is "tuberculoid," which induces a cell-mediated response that limits its growth. Through this form, M. leprae multiplies at the site of entry, usually the skin, invading and colonizing Schwann cells. The microbe then induces T-helper lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and giant cell infiltration of the skin, causing infected individuals to exhibit large flattened patches with raised and elevated red edges on their skin. These patches have dry, pale, hairless centers, accompanied by a loss of sensation on the skin. The loss of sensation may develop as a result of invasion of the peripheral sensory nerves. The macule at the cutaneous site of entry and the loss of pain sensation are key clinical indications that an individual has a tuberculoid form of leprosy. [25]

The second form of leprosy is the "lepromatous" form, in which the microbes proliferate within the macrophages at the site of entry. They also grow within the epithelial tissues of the face and ear lobes. The suppressor T-cells that are induced are numerous, but the epithelioid and giant cells are rare or absent. With cell-mediated immunity impaired, large numbers of M. leprae appear in the macrophages and the infected patients develop papules at the entry site, marked by a folding of the skin. Gradual destruction of cutaneous nerves lead to what is referred to as "classic lion face." Extensive penetration of this microbe may lead to severe body damage; for example the loss of bones, fingers, and toes.[25]

Symptoms of Mycobacterium leprae

The symptoms of M. leprae, also known as leprosy, are unattractive skin sores that are pale in color, lumps or bumps that do not go away after several weeks or months, nerve damage which can lead to complications with the ability to sense feeling in the arms and legs as well as muscle weakness. Symptoms usually take 3–5 years from being exposed to manifest within the body. However, some individuals do not begin to show symptoms until 20 years after exposure to the disease. This long incubation period makes the ability to properly be able to diagnose when an individual came into contact with the disease very difficult.[26]

Diagnostic criteria for leprosy

Testing to aid in the diagnosis of leprosy are still needed, but this study attempts to use LID-1 (Leprosy IDRI Diagnostic-1). This is a fusion protein that has been recognized in genome of Mycobacterium leprae as an antigen in diagnostic testing for leprosy.[27] Key symptoms that lead to diagnosis of leprosy include hypopigmentation with a loss of sensation, thickened peripheral nerves, and acid-fast staining in slit skin smears. The main problem with the identification of leprosy is the lack of sufficient knowledge of early signs of infections by M. leprae. Without enough expertise by clinicians, the cardinal signs are missed and providing confident differential diagnosis will decline.[28] The diagnosis of leprosy is primarily a clinical one. In one Ethiopian study, the following criteria had a sensitivity of 94% with a positive predictive value of 98% in diagnosing leprosy. Diagnosis was based on one or more of three signs:

- Hypopigmented or reddish skin patches with definite loss of sensation

- Thickened peripheral nerves

- Acid-fast bacilli on skin smears or biopsy material

Treatment

Multidrug therapy (MDT) was recommended by WHO Expert Committee in 1984, and became the standard leprosy treatment. MDT has been supplied by WHO for free since 1995 to endemic countries. MDT is used to treat leprosy because treatment of leprosy with one drug (monotherapy) can result in drug resistance. The drug combination used in MDT will depend on the classification of the disease. WHO recommends patients with multibacillary leprosy use a combination of Rifampicin, Clofazimine, and Dapsone for 12 months. WHO recommends patients with paulibacilalry leprosy use combination of Rifampicin and Dapsone for a duration of 6 months.[29] Antibiotics must be taken regularly until treatment is complete due to the fact M. leprae has the ability to grow back.[30]

A preventive measure of M. leprae is to avoid close contact with infectious people who are untreated.[31] Blindness, crippling of the hands and feet, and paralysis are all effects of nerve damage associated with untreated M. leprae. Treatment does not reverse the nerve damage done, which is why it is recommended to get treated as soon as possible.[30] The Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine offers a variable amount of protection against leprosy in addition to its main target of tuberculosis.[32]

References

- "Mycobacterium Leprae, the Cause of Leprosy". Microbiology Society. August 27, 2014. Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- Hansen, G. Armauer (1874). Undersøgelser Angående Spedalskhedens Årsager [Investigations concerning the etiology of leprosy]. OCLC 969496922. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- McMurray DN (1996). "Mycobacteria and Nocardia.". In Baron S.; et al. (eds.). Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Microbiology of M.leprae". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013.

- Brennan, PatrickJ; Spencer, JohnStewart (September 5, 2019). "The Physiology of Mycobacterium leprae". www.internationaltextbookofleprosy.org. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- Shinnick, Thomas M. (2006). "Mycobacterium leprae". In Dworkin, Martin; Falkow, Stanley; Rosenberg, Eugene; Schleifer, Karl-Heinz; Stackebrandt, Erko (eds.). The Prokaryotes. Springer. pp. 934–44. doi:10.1007/0-387-30743-5_35. ISBN 978-0-387-25493-7. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Draper, Philip (March 1, 1983). "The bacteriology of Mycobacterium leprae". Tubercle. 64 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1016/0041-3879(83)90050-8. ISSN 0041-3879. PMID 6405519. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- Ramesh Marne Bhat and Chaitra Prakash (September 2012). "Leprosy: An Overview of Pathophysiology". Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012: 181089. doi:10.1155/2012/181089. PMC 3440852. PMID 22988457.

- Thomas P.Gillis (2015). "Mycobacterium leprae". Molecular Medical Microbiology (Second Edition): 1655–1668. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-397169-2.00093-7. ISBN 9780123971692.

- Sharma, Rahul; Singh, Pushpendra; Loughry, W.J.; Lockhart, J. Mitchell; Inman, W. Barry; Duthie, Malcolm S.; Pena, Maria T.; Marcos, Luis A.; Scollard, David M.; Cole, Stewart T.; Truman, Richard W. (2015). "Zoonotic Leprosy in the Southeastern United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 21 (12): 2127–34. doi:10.3201/eid2112.150501. PMC 4672434. PMID 26583204.

- "Mycobacterium leprae". Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- Truman RW, Krahenbuhl JL; Krahenbuhl (2001). "Viable M. leprae as a research reagent". Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 69 (1): 1–12. PMID 11480310.

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, et al. (1998). "Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence". Nature. 393 (6685): 537–44. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..537C. doi:10.1038/31159. PMID 9634230.

- Chavarro-Portillo, Bibiana; Soto, Carlos Yesid; Guerrero, Martha Inírida (September 1, 2019). "Mycobacterium leprae's evolution and environmental adaptation". Acta Tropica. 197: 105041. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105041. ISSN 0001-706X.

- Cole ST, Eiglmeier K, Parkhill J, et al. (2001). "Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus". Nature. 409 (6823): 1007–11. Bibcode:2001Natur.409.1007C. doi:10.1038/35059006. PMID 11234002. S2CID 4307207.

- Narayanan S, Deshpande U; Deshpande (2013). "Whole-Genome Sequences of Four Clinical Isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Tamil Nadu, South India". Genome Announc. 1 (3): e00186–13. doi:10.1128/genomeA.00186-13. PMC 3707582. PMID 23788533.

- Schuenemann VJ, Singh P, Mendum TA, et al. (July 2013). "Genome-wide comparison of medieval and modern Mycobacterium leprae". Science. 341 (6142): 179–83. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..179S. doi:10.1126/science.1238286. PMID 23765279. S2CID 22760148.

- "Risk of Exposure | Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on July 19, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- Singh P, Benjak A, Schuenemann VJ, Herbig A, Avanzi C, Busso P, Nieselt K, Krause J, Vera-Cabrera L, Cole ST (2015). "Insight into the evolution and origin of leprosy bacilli from the genome sequence of Mycobacterium lepromatosis". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 112 (14): 4459–64. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.4459S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421504112. PMC 4394283. PMID 25831531.

- Schuenemann VJ, Singh P, Mendum TA, Krause-Kyora B, Jager G, et al. (2013). "Genome-wide comparison of medieval and modern Mycobacterium leprae". Science. 341 (6142): 179–83. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..179S. doi:10.1126/science.1238286. PMID 23765279. S2CID 22760148.

- Djelouadji Z, Raoult D, Drancourt M (2011). "Palaeogenomics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: epidemic bursts with a degrading genome". Lancet Infect Dis. 11 (8): 641–50. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(11)70093-7. PMID 21672667.

- Monot M, Honoré N, Garnier T, Araoz R, Coppée JY, Lacroix C, Sow S, Spencer JS, Truman RW, Williams DL, Gelber R, Virmond M, Flageul B, Cho SN, Ji B, Paniz-Mondolfi A, Convit J, Young S, Fine PE, Rasolofo V, Brennan PJ, Cole ST (2005). "On the origin of leprosy". Science. 308 (5724): 1040–42. doi:10.1126/science/1109759. PMID 15894530. S2CID 86109194. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- "Leprosy". www.who.int. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- "Leprosy (Hansen's disease) – Blue Book – Department of Health and Human services, Victoria, Australia". ideas.health.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on November 8, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- Frade MA, Coltro PS, Filho FB, Horácio GS, Neto AA, da Silva VZ, Westin AT, Guimarães FR, Innocentini LM, Motta AC, Farina JA (2022). "Lucio's phenomenon: A systematic literature review of definition, clinical features, histopathogenesis and management". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 88 (4): 464–477. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_909_19. PMID 34672479.

- "Leprosy Overview". WebMD. Archived from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- "Application of Mycobacterium Leprae-specific cellular and serological tests for the differential diagnosis of leprosy from confounding dermatoses". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 86 (2): 163–168. October 1, 2016. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.07.024. ISSN 0732-8893.

- "Application of Mycobacterium Leprae-specific cellular and serological tests for the differential diagnosis of leprosy from confounding dermatoses". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 86 (2): 163–168. October 1, 2016. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.07.024. ISSN 0732-8893.

- World Health Organization. "Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy." (2018).

- "Diagnosis and Treatment | Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. November 2, 2018. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- "Leprosy: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- Duthie MS, Gillis TP, Reed SG; Gillis; Reed (November 2011). "Advances and hurdles on the way toward a leprosy vaccine". Hum Vaccin. 7 (11): 1172–83. doi:10.4161/hv.7.11.16848. PMC 3323495. PMID 22048122.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- The genome of Mycobacterium leprae

- "Mycobacterium leprae". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 1769.