History of Africa

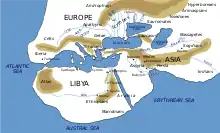

The history of Africa begins with the emergence of hominids, archaic humans and - around 300–250,000 years ago—anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens), in East Africa, and continues unbroken into the present as a patchwork of diverse and politically developing nation states.[1] The earliest known recorded history arose in Ancient Egypt, and later in Nubia, the Sahel, the Maghreb, and the Horn of Africa.

| Part of a series on |

| Human history Human Era |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

Following the desertification of the Sahara, North African history became entwined with the Middle East and Southern Europe while the Bantu expansion swept from modern day Cameroon (Central Africa) across much of the sub-Saharan continent in waves between around 1000 BC and 1 AD, creating a linguistic commonality across much of the central and Southern continent.[2]

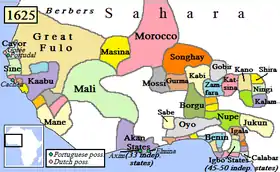

During the Middle Ages, Islam spread west from Arabia to Egypt, crossing the Maghreb and the Sahel. Some notable pre-colonial states and societies in Africa include the Ajuran Empire, Bachwezi Empire, D'mt, Adal Sultanate, Alodia, Warsangali Sultanate, Buganda Kingdom, Kingdom of Nri, Nok culture, Mali Empire, Bono State, Songhai Empire, Benin Empire, Oyo Empire, Kingdom of Lunda (Punu-yaka), Ashanti Empire, Ghana Empire, Mossi Kingdoms, Mutapa Empire, Kingdom of Mapungubwe, Kingdom of Sine, Kingdom of Sennar, Kingdom of Saloum, Kingdom of Baol, Kingdom of Cayor, Kingdom of Zimbabwe, Kingdom of Kongo, Empire of Kaabu, Kingdom of Ile Ife, Ancient Carthage, Numidia, Mauretania, and the Aksumite Empire. At its peak, prior to European colonialism, it is estimated that Africa had up to 10,000 different states and autonomous groups with distinct languages and customs.[3][4]

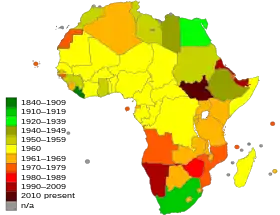

From the late 15th century, Europeans joined the slave trade.[5] That includes the triangular trade, with the Portuguese initially acquiring slaves through trade and later by force as part of the Atlantic slave trade. They transported enslaved West, Central, and Southern Africans overseas.[6] Subsequently, European colonization of Africa developed rapidly from around 10% (1870) to over 90% (1914) in the Scramble for Africa (1881–1914). However following struggles for independence in many parts of the continent, as well as a weakened Europe after the Second World War (1939–1945), decolonization took place across the continent, culminating in the 1960 Year of Africa.[7]

Disciplines such as recording of oral history, historical linguistics, archaeology, and genetics have been vital in rediscovering the great African civilizations of antiquity.

Prehistory

Paleolithic

The first known hominids evolved in Africa. According to paleontology, the early hominids' skull anatomy was similar to that of the gorilla and the chimpanzee, great apes that also evolved in Africa, but the hominids had adopted a bipedal locomotion which freed their hands. This gave them a crucial advantage, enabling them to live in both forested areas and on the open savanna at a time when Africa was drying up and the savanna was encroaching on forested areas. This would have occurred 10 to 5 million years ago, but these claims are controversial because biologists and genetics have humans appearing around the last 70 thousand to 200 thousand years.[8]

By 4 million years ago, several australopithecine hominid species had developed throughout Southern, Eastern and Central Africa. They were tool users, and makers of tools. They scavenged for meat and were omnivores.[8]

By approximately 3.3 million years ago, primitive stone tools were first used to scavenge kills made by other predators and to harvest carrion and marrow from their bones. In hunting, Homo habilis was probably not capable of competing with large predators and was still more prey than hunter. H. habilis probably did steal eggs from nests and may have been able to catch small game and weakened larger prey (cubs and older animals). The tools were classed as Oldowan.[9]

Around 1.8 million years ago, Homo ergaster first appeared in the fossil record in Africa. From Homo ergaster, Homo erectus evolved 1.5 million years ago. Some of the earlier representatives of this species were still fairly small-brained and used primitive stone tools, much like H. habilis. The brain later grew in size, and H. erectus eventually developed a more complex stone tool technology called the Acheulean. Possibly the first hunters, H. erectus mastered the art of making fire and was the first hominid to leave Africa, colonizing most of Afro-Eurasia and perhaps later giving rise to Homo floresiensis. Although some recent writers have suggested that Homo georgicus was the first and primary hominid ever to live outside Africa, many scientists consider H. georgicus to be an early and primitive member of the H. erectus species.[10][11]

The fossil record shows Homo sapiens (also known as "modern humans" or "anatomically modern humans") living in Africa by about 350,000-260,000 years ago. The earliest known Homo sapiens fossils include the Jebel Irhoud remains from Morocco (c. 315,000 years ago),[12] the Florisbad Skull from South Africa (c. 259,000 years ago), and the Omo remains from Ethiopia (c. 233,000 years ago).[13][14][15][16][17] Scientists have suggested that Homo sapiens may have arisen between 350,000 and 260,000 years ago through a merging of populations in East Africa and South Africa.[18][19]

Evidence of a variety of behaviors indicative of Behavioral modernity date to the African Middle Stone Age, associated with early Homo sapiens and their emergence. Abstract imagery, widened subsistence strategies, and other "modern" behaviors have been discovered from that period in Africa, especially South, North, and East Africa. The Blombos Cave site in South Africa, for example, is famous for rectangular slabs of ochre engraved with geometric designs. Using multiple dating techniques, the site was confirmed to be around 77,000 and 100–75,000 years old.[20][21] Ostrich egg shell containers engraved with geometric designs dating to 60,000 years ago were found at Diepkloof, South Africa.[22] Beads and other personal ornamentation have been found from Morocco which might be as much as 130,000 years old; as well, the Cave of Hearths in South Africa has yielded a number of beads dating from significantly prior to 50,000 years ago,[23] and shell beads dating to about 75,000 years ago have been found at Blombos Cave, South Africa.[24][25][26]

Specialized projectile weapons as well have been found at various sites in Middle Stone Age Africa, including bone and stone arrowheads at South African sites such as Sibudu Cave (along with an early bone needle also found at Sibudu) dating approximately 60,000-70,000 years ago,[27][28][29][30][31] and bone harpoons at the Central African site of Katanda dating to about 90,000 years ago.[32] Evidence also exists for the systematic heat treating of silcrete stone to increase its flake-ability for the purpose of toolmaking, beginning approximately 164,000 years ago at the South African site of Pinnacle Point and becoming common there for the creation of microlithic tools at about 72,000 years ago.[33][34] Early stone-tipped projectile weapons (a characteristic tool of Homo sapiens), the stone tips of javelins or throwing spears, were discovered in 2013 at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, and date to around 279,000 years ago.[35]

In 2008, an ochre processing workshop likely for the production of paints was uncovered dating to ca. 100,000 years ago at Blombos Cave, South Africa. Analysis shows that a liquefied pigment-rich mixture was produced and stored in the two abalone shells, and that ochre, bone, charcoal, grindstones and hammer-stones also formed a composite part of the toolkits. Evidence for the complexity of the task includes procuring and combining raw materials from various sources (implying they had a mental template of the process they would follow), possibly using pyrotechnology to facilitate fat extraction from bone, using a probable recipe to produce the compound, and the use of shell containers for mixing and storage for later use.[36][37][38] Modern behaviors, such as the making of shell beads, bone tools and arrows, and the use of ochre pigment, are evident at a Kenyan site by 78,000-67,000 years ago.[39]

Expanding subsistence strategies beyond big-game hunting and the consequential diversity in tool types has been noted as signs of behavioral modernity. A number of South African sites have shown an early reliance on aquatic resources from fish to shellfish. Pinnacle Point, in particular, shows exploitation of marine resources as early as 120,000 years ago, perhaps in response to more arid conditions inland.[40] Establishing a reliance on predictable shellfish deposits, for example, could reduce mobility and facilitate complex social systems and symbolic behavior. Blombos Cave and Site 440 in Sudan both show evidence of fishing as well. Taphonomic change in fish skeletons from Blombos Cave have been interpreted as capture of live fish, clearly an intentional human behavior.[23] Humans in North Africa (Nazlet Sabaha,[41] Egypt) are known to have dabbled in chert mining, as early as ≈100,000 years ago, for the construction of stone tools.[42][43]

Evidence was found in 2018, dating to about 320,000 years ago, at the Kenyan site of Olorgesailie, of the early emergence of modern behaviors including: long-distance trade networks (involving goods such as obsidian), the use of pigments, and the possible making of projectile points. It is observed by the authors of three 2018 studies on the site, that the evidence of these behaviors is approximately contemporary to the earliest known Homo sapiens fossil remains from Africa (such as at Jebel Irhoud and Florisbad), and they suggest that complex and modern behaviors began in Africa around the time of the emergence of Homo sapiens.[44][45][46] In 2019, further evidence of early complex projectile weapons in Africa was found at Adouma, Ethiopia dated 80,000-100,000 years ago, in the form of points considered likely to belong to darts delivered by spear throwers.[47]

Around 65–50,000 years ago, the species' expansion out of Africa launched the colonization of the planet by modern human beings.[48][49][50][51] By 10,000 BC, Homo sapiens had spread to most corners of Afro-Eurasia. Their dispersals are traced by linguistic, cultural and genetic evidence.[9][52][53] The earliest physical evidence of astronomical activity may be a lunar calendar found on the Ishango bone dated to between 23,000 and 18,000 BC from in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[54] However, this interpretation of the object's purpose is disputed.[55]

Scholars have argued that warfare was absent throughout much of humanity's prehistoric past, and that it emerged from more complex political systems as a result of sedentism, agricultural farming, etc.[56] However, the findings at the site of Nataruk in Turkana County, Kenya, where the remains of 27 individuals who died as the result of an intentional attack by another group 10,000 years ago, suggest that inter-human conflict has a much longer history.[57]

Emergence of agriculture and desertification of the Sahara

Around 16,000 BC, from the Red Sea Hills to the northern Ethiopian Highlands, nuts, grasses and tubers were being collected for food. By 13,000 to 11,000 BC, people began collecting wild grains. This spread to Western Asia, which domesticated its wild grains, wheat and barley. Between 10,000 and 8000 BC, Northeast Africa was cultivating wheat and barley and raising sheep and cattle from Southwest Asia. A wet climatic phase in Africa turned the Ethiopian Highlands into a mountain forest. Omotic speakers domesticated enset around 6500–5500 BC. Around 7000 BC, the settlers of the Ethiopian highlands domesticated donkeys, and by 4000 BC domesticated donkeys had spread to Southwest Asia. Cushitic speakers, partially turning away from cattle herding, domesticated teff and finger millet between 5500 and 3500 BC.[58][59]

During the 11th millennium BP, pottery was independently invented in Africa, with the earliest pottery there dating to about 9,400 BC from central Mali.[60] It soon spread throughout the southern Sahara and Sahel.[61] In the steppes and savannahs of the Sahara and Sahel in Northern West Africa, the Nilo-Saharan speakers and Mandé peoples started to collect and domesticate wild millet, African rice and sorghum between 8000 and 6000 BC. Later, gourds, watermelons, castor beans, and cotton were also collected and domesticated. The people started capturing wild cattle and holding them in circular thorn hedges, resulting in domestication.[62] They also started making pottery and built stone settlements (e.g., Tichitt, Oualata). Fishing, using bone-tipped harpoons, became a major activity in the numerous streams and lakes formed from the increased rains.[63] Mande peoples have been credited with the independent development of agriculture about 4000–3000 BC.[64]

In West Africa, the wet phase ushered in an expanding rainforest and wooded savanna from Senegal to Cameroon. Between 9000 and 5000 BC, Niger–Congo speakers domesticated the oil palm and raffia palm. Two seed plants, black-eyed peas and voandzeia (African groundnuts), were domesticated, followed by okra and kola nuts. Since most of the plants grew in the forest, the Niger–Congo speakers invented polished stone axes for clearing forest.[65]

Most of Southern Africa was occupied by pygmy peoples and Khoisan who engaged in hunting and gathering. Some of the oldest rock art was produced by them.[66]

For several hundred thousand years the Sahara has alternated between desert and savanna grassland in a 41,000 year cycle caused by changes ("precession") in the Earth's axis as it rotates around the sun which change the location of the North African Monsoon.[67] When the North African monsoon is at its strongest annual precipitation and subsequent vegetation in the Sahara region increase, resulting in conditions commonly referred to as the "green Sahara". For a relatively weak North African monsoon, the opposite is true, with decreased annual precipitation and less vegetation resulting in a phase of the Sahara climate cycle known as the "desert Sahara". The Sahara has been a desert for several thousand years, and is expected to become green again in about 15,000 years time (17,000 AD).[68]

Just prior to Saharan desertification, the communities that developed south of Egypt, in what is now Sudan, were full participants in the Neolithic revolution and lived a settled to semi-nomadic lifestyle, with domesticated plants and animals.[69] It has been suggested that megaliths found at Nabta Playa are examples of the world's first known archaeoastronomical devices, predating Stonehenge by some 1,000 years.[70] The sociocultural complexity observed at Nabta Playa and expressed by different levels of authority within the society there has been suggested as forming the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom of Egypt.[71] By 5000 BC, Africa entered a dry phase, and the climate of the Sahara region gradually became drier. The population trekked out of the Sahara region in all directions, including towards the Nile Valley below the Second Cataract, where they made permanent or semipermanent settlements. A major climatic recession occurred, lessening the heavy and persistent rains in Central and Eastern Africa.

Central Africa

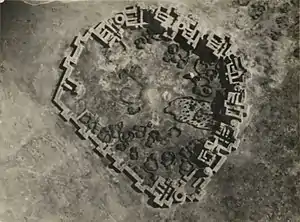

Archaeological findings in Central Africa have been discovered dating back to over 100,000 years.[72] Extensive walled sites and settlements have recently been found in Zilum, Chad approximately 60 km (37 mi) southwest of Lake Chad dating to the first millennium BC.[73][74]

Trade and improved agricultural techniques supported more sophisticated societies, leading to the early civilizations of Sao, Kanem, Bornu, Shilluk, Baguirmi, and Wadai.[75]

Around 1,000 BC, Bantu migrants had reached the Great Lakes Region in Central Africa. Halfway through the first millennium BC, the Bantu had also settled as far south as what is now Angola.[76]

Metallurgy

Evidence of the early smelting of metals – lead, copper, and bronze – dates from the fourth millennium BC.[77]

Egyptians smelted copper during the predynastic period, and bronze came into use after 3,000 BC at the latest[78] in Egypt and Nubia. Nubia became a major source of copper as well as of gold.[79] The use of gold and silver in Egypt dates back to the predynastic period.[80][81]

In the Aïr Mountains of present-day Niger people smelted copper independently of developments in the Nile valley between 3,000 and 2,500 BC. They used a process unique to the region, suggesting that the technology was not brought in from outside; it became more mature by about 1,500 BC.[81]

By the 1st millennium BC iron working had reached Northwestern Africa, Egypt, and Nubia.[82] Zangato and Holl document evidence of iron-smelting in the Central African Republic and Cameroon that may date back to 3,000 to 2,500 BC.[83] Assyrians using iron weapons pushed Nubians out of Egypt in 670 BC, after which the use of iron became widespread in the Nile valley.[84]

The theory that iron spread to Sub-Saharan Africa via the Nubian city of Meroe[85] is no longer widely accepted, and some researchers believe that sub-Saharan Africans invented iron metallurgy independently. Metalworking in West Africa has been dated as early as 2,500 BC at Egaro west of the Termit in Niger, and iron working was practiced there by 1,500 BC.[86] Iron smelting has been dated to 2,000 BC in southeast Nigeria.[87] Central Africa provides possible evidence of iron working as early as the 3rd millennium BC.[88] Iron smelting developed in the area between Lake Chad and the African Great Lakes between 1,000 and 600 BC, and in West Africa around 2,000 BC, long before the technology reached Egypt. Before 500 BC, the Nok culture in the Jos Plateau was already smelting iron.[89][90][91][92][93][94] Archaeological sites containing iron-smelting furnaces and slag have been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in Igboland: dating to 2,000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[87][95] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[95] The site of Gbabiri (in the Central African Republic) has also yielded evidence of iron metallurgy, from a reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop; with earliest dates of 896-773 BC and 907-796 BC respectively.[94]

Antiquity

The ancient history of North Africa is inextricably linked to that of the Ancient Near East. This is particularly true of Ancient Egypt and Nubia. In the Horn of Africa the Kingdom of Aksum ruled modern-day Eritrea, northern Ethiopia and the coastal area of the western part of the Arabian Peninsula. The Ancient Egyptians established ties with the Land of Punt in 2,350 BC. Punt was a trade partner of Ancient Egypt and it is believed that it was located in modern-day Somalia, Djibouti or Eritrea.[96] Phoenician cities such as Carthage were part of the Mediterranean Iron Age and classical antiquity. Sub-Saharan Africa developed more or less independently in those times.

Ancient Egypt

After the desertification of the Sahara, settlement became concentrated in the Nile Valley, where numerous sacral chiefdoms appeared. The regions with the largest population pressure were in the Nile Delta region of Lower Egypt, in Upper Egypt, and also along the second and third cataracts of the Dongola Reach of the Nile in Nubia.[97] This population pressure and growth was brought about by the cultivation of southwest Asian crops, including wheat and barley, and the raising of sheep, goats, and cattle. Population growth led to competition for farm land and the need to regulate farming. Regulation was established by the formation of bureaucracies among sacral chiefdoms. The first and most powerful of the chiefdoms was Ta-Seti, founded around 3,500 BC. The idea of sacral chiefdom spread throughout Upper and Lower Egypt.[98]

Later consolidation of the chiefdoms into broader political entities began to occur in Upper and Lower Egypt, culminating into the unification of Egypt into one political entity by Narmer (Menes) in 3,100 BC. Instead of being viewed as a sacral chief, he became a divine king. The henotheism, or worship of a single god within a polytheistic system, practiced in the sacral chiefdoms along Upper and Lower Egypt, became the polytheistic Ancient Egyptian religion. Bureaucracies became more centralized under the pharaohs, run by viziers, governors, tax collectors, generals, artists, and technicians. They engaged in tax collecting, organizing of labor for major public works, and building irrigation systems, pyramids, temples, and canals. During the Fourth Dynasty (2,620–2,480 BC), long-distance trade was developed, with the Levant for timber, with Nubia for gold and skins, with Punt for frankincense, and also with the western Libyan territories. For most of the Old Kingdom, Egypt developed her fundamental systems, institutions and culture, always through the central bureaucracy and by the divinity of the Pharaoh.[99]

After the fourth millennium BC, Egypt started to extend direct military and political control over her southern and western neighbors. By 2,200 BC, the Old Kingdom's stability was undermined by rivalry among the governors of the nomes who challenged the power of pharaohs and by invasions of Asiatics into the Nile Delta. The First Intermediate Period had begun, a time of political division and uncertainty.[99]

Middle Kingdom of Egypt arose when Mentuhotep II of Eleventh Dynasty unified Egypt once again between 2041 and 2016 BC beginning with his conquering of Tenth Dynasty in 2041 BC.[100][101] Pyramid building resumed, long-distance trade re-emerged, and the center of power moved from Memphis to Thebes. Connections with the southern regions of Kush, Wawat and Irthet at the second cataract were made stronger. Then came the Second Intermediate Period, with the invasion of the Hyksos on horse-drawn chariots and utilizing bronze weapons, a technology heretofore unseen in Egypt. Horse-drawn chariots soon spread to the west in the inhabitable Sahara and North Africa. The Hyksos failed to hold on to their Egyptian territories and were absorbed by Egyptian society. This eventually led to one of Egypt's most powerful phases, the New Kingdom (1,580–1,080 BC), with the Eighteenth Dynasty. Egypt became a superpower controlling Nubia and Judea while exerting political influence on the Libyans to the West and on the Mediterranean.[99]

As before, the New Kingdom ended with invasion from the west by Libyan princes, leading to the Third Intermediate Period. Beginning with Shoshenq I, the Twenty-second Dynasty was established. It ruled for two centuries.[99]

To the south, Nubian independence and strength was being reasserted. This reassertion led to the conquest of Egypt by Nubia, begun by Kashta and completed by Piye (Pianhky, 751–730 BC) and Shabaka (716–695 BC). This was the birth of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. The Nubians tried to re-establish Egyptian traditions and customs. They ruled Egypt for a hundred years. This was ended by an Assyrian invasion, with Taharqa experiencing the full might of Assyrian iron weapons. The Nubian pharaoh Tantamani was the last of the Twenty-fifth dynasty.[99]

When the Assyrians and Nubians left, a new Twenty-sixth Dynasty emerged from Sais. It lasted until 525 BC, when Egypt was invaded by the Persians. Unlike the Assyrians, the Persians stayed. In 332, Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great. This was the beginning of the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ended with Roman conquest in 30 BC. Pharaonic Egypt had come to an end.[99]

Nubia

Around 3,500 BC, one of the first sacral kingdoms to arise in the Nile was Ta-Seti, located in northern Nubia. Ta-Seti was a powerful sacral kingdom in the Nile Valley at the 1st and 2nd cataracts that exerted an influence over nearby chiefdoms based on pictorial representation ruling over Upper Egypt. Ta-Seti traded as far as Syro-Palestine, as well as with Egypt. Ta-Seti exported gold, copper, ostrich feathers, ebony and ivory to the Old Kingdom. By the 32nd century BC, Ta-Seti was in decline. After the unification of Egypt by Narmer in 3,100 BC, Ta-Seti was invaded by the Pharaoh Hor-Aha of the First Dynasty, destroying the final remnants of the kingdom. Ta-Seti is affiliated with the A-Group Culture known to archaeology.[102]

Small sacral kingdoms continued to dot the Nubian portion of the Nile for centuries after 3,000 BC. Around the latter part of the third millennium, there was further consolidation of the sacral kingdoms. Two kingdoms in particular emerged: the Sai kingdom, immediately south of Egypt, and the Kingdom of Kerma at the third cataract. Sometime around the 18th century BC, the Kingdom of Kerma conquered the Kingdom of Sai, becoming a serious rival to Egypt. Kerma occupied a territory from the first cataract to the confluence of the Blue Nile, White Nile, and Atbarah River. About 1,575 to 1,550 BC, during the latter part of the Seventeenth Dynasty, the Kingdom of Kerma invaded Egypt.[103] The Kingdom of Kerma allied itself with the Hyksos invasion of Egypt.[104]

Egypt eventually re-energized under the Eighteenth Dynasty and conquered the Kingdom of Kerma or Kush, ruling it for almost 500 years. The Kushites were Egyptianized during this period. By 1100 BC, the Egyptians had withdrawn from Kush. The region regained independence and reasserted its culture. Kush built a new religion around Amun and made Napata its spiritual center. In 730 BC, the Kingdom of Kush invaded Egypt, taking over Thebes and beginning the Nubian Empire. The empire extended from Palestine to the confluence of the Blue Nile, the White Nile, and River Atbara.[105]

In 664 BC, the Kushites were expelled from Egypt by iron-wielding Assyrians. Later, the administrative capital was moved from Napata to Meröe, developing a new Nubian culture. Initially, Meroites were highly Egyptianized, but they subsequently began to take on distinctive features. Nubia became a center of iron-making and cotton cloth manufacturing. Egyptian writing was replaced by the Meroitic alphabet. The lion god Apedemak was added to the Egyptian pantheon of gods. Trade links to the Red Sea increased, linking Nubia with Mediterranean Greece. Its architecture and art diversified, with pictures of lions, ostriches, giraffes, and elephants. Eventually, with the rise of Aksum, Nubia's trade links were broken and it suffered environmental degradation from the tree cutting required for iron production. In 350 AD, the Aksumite king Ezana brought Meröe to an end.[106]

Carthage

The Egyptians referred to the people west of the Nile, ancestral to the Berbers, as Libyans. The Libyans were agriculturalists like the Mauri of Morocco and the Numidians of central and eastern Algeria and Tunis. They were also nomadic, having the horse, and occupied the arid pastures and desert, like the Gaetuli. Berber desert nomads were typically in conflict with Berber coastal agriculturalists.[107]

The Phoenicians were Mediterranean seamen in constant search for valuable metals such as copper, gold, tin, and lead. They began to populate the North African coast with settlements—trading and mixing with the native Berber population. In 814 BC, Phoenicians from Tyre established the city of Carthage.[108] By 600 BC, Carthage had become a major trading entity and power in the Mediterranean, largely through trade with tropical Africa. Carthage's prosperity fostered the growth of the Berber kingdoms, Numidia and Mauretania. Around 500 BC, Carthage provided a strong impetus for trade with Sub-Saharan Africa. Berber middlemen, who had maintained contacts with Sub-Saharan Africa since the desert had desiccated, utilized pack animals to transfer products from oasis to oasis. Danger lurked from the Garamantes of Fez, who raided caravans. Salt and metal goods were traded for gold, slaves, beads, and ivory.[109]

The Carthaginians were rivals to the Greeks and Romans. Carthage fought the Punic Wars, three wars with Rome: the First Punic War (264 to 241 BC), over Sicily; the Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC), in which Hannibal invaded Europe; and the Third Punic War (149 to 146 BC). Carthage lost the first two wars, and in the third it was destroyed, becoming the Roman province of Africa, with the Berber Kingdom of Numidia assisting Rome. The Roman province of Africa became a major agricultural supplier of wheat, olives, and olive oil to imperial Rome via exorbitant taxation. Two centuries later, Rome brought the Berber kingdoms of Numidia and Mauretania under its authority. In the 420's AD, Vandals invaded North Africa and Rome lost her territories, subsequently the Berber kingdoms regained their independence.[110]

Christianity gained a foothold in Africa at Alexandria in the 1st century AD and spread to Northwest Africa. By 313 AD, with the Edict of Milan, all of Roman North Africa was Christian. Egyptians adopted Monophysite Christianity and formed the independent Coptic Church. Berbers adopted Donatist Christianity. Both groups refused to accept the authority of the Roman Catholic Church.[111]

Role of the Berbers

As Carthaginian power grew, its impact on the indigenous population increased dramatically. Berber civilization was already at a stage in which agriculture, manufacturing, trade, and political organization supported several states. Trade links between Carthage and the Berbers in the interior grew, but territorial expansion also resulted in the enslavement or military recruitment of some Berbers and in the extraction of tribute from others. By the early 4th century BC, Berbers formed one of the largest element, with Gauls, of the Carthaginian army.

In the Mercenary War (241-238 BC), a rebellion was instigated by mercenary soldiers of Carthage and African allies.[112] Berber soldiers participated after being unpaid following the defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War. Berbers succeeded in obtaining control of much of Carthage's North African territory, and they minted coins bearing the name Libyan, used in Greek to describe natives of North Africa. The Carthaginian state declined because of successive defeats by the Romans in the Punic Wars; in 146 BC the city of Carthage was destroyed. As Carthaginian power waned, the influence of Berber leaders in the hinterland grew. By the 2nd century BC, several large but loosely administered Berber kingdoms had emerged. Two of them were established in Numidia, behind the coastal areas controlled by Carthage. West of Numidia lay Mauretania, which extended across the Moulouya River in Morocco to the Atlantic Ocean. The high point of Berber civilization, unequaled until the coming of the Almohads and Almoravid dynasty more than a millennium later, was reached during the reign of Masinissa in the 2nd century BC. After Masinissa's death in 148 BC, the Berber kingdoms were divided and reunited several times. Masinissa's line survived until 24 AD, when the remaining Berber territory was annexed to the Roman Empire.

Macrobia and the Barbari City States

Macrobia was an ancient kingdom situated in the Horn of Africa (Present day Somalia) it is mentioned in the 5th century BC. According to Herodotus' account, the Persian Emperor Cambyses II upon his conquest of Egypt (525 BC) sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based at least in part on stature, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to string it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.[113][114][115]

The Macrobians were a regional power reputed for their advanced architecture and gold wealth, which was so plentiful that they shackled their prisoners in golden chains.[114]

After the collapse of Macrobia, several wealthy ancient city-states, such as Opone, Essina, Sarapion, Nikon, Malao, Damo and Mosylon near Cape Guardafui would emerge from the 1st millennium BC–500 AD to compete with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the wealthy Indo-Greco-Roman trade and flourished along the Somali coast. They developed a lucrative trading network under a region collectively known in the Peripilus of the Erythraean Sea as Barbaria.[116]

Roman North Africa

"Increases in urbanization and in the area under cultivation during Roman rule caused wholesale dislocations of the Berber society, forcing nomad tribes to settle or to move from their traditional rangelands. Sedentary tribes lost their autonomy and connection with the land. Berber opposition to the Roman presence was nearly constant. The Roman emperor Trajan established a frontier in the south by encircling the Aurès and Nemencha mountains and building a line of forts from Vescera (modern Biskra) to Ad Majores (Henchir Besseriani,[117] southeast of Biskra). The defensive line extended at least as far as Castellum Dimmidi (modern Messaâd, southwest of Biskra), Roman Algeria's southernmost fort. Romans settled and developed the area around Sitifis (modern Sétif) in the 2nd century, but farther west the influence of Rome did not extend beyond the coast and principal military roads until much later."[118]

The Roman military presence of North Africa remained relatively small, consisting of about 28,000 troops and auxiliaries in Numidia and the two Mauretanian provinces. Starting in the 2nd century AD, these garrisons were manned mostly by local inhabitants.[119]

Aside from Carthage, urbanization in North Africa came in part with the establishment of settlements of veterans under the Roman emperors Claudius (reigned 41–54), Nerva (96–98), and Trajan (98–117). In Algeria such settlements included Tipasa, Cuicul or Curculum (modern Djemila, northeast of Sétif), Thamugadi (modern Timgad, southeast of Sétif), and Sitifis (modern Sétif). The prosperity of most towns depended on agriculture. Called the "granary of the empire", North Africa became one of the largest exporters of grain in the empire, shipping to the provinces which did not produce cereals, like Italy and Greece. Other crops included fruit, figs, grapes, and beans. By the 2nd century AD, olive oil rivaled cereals as an export item.[120]

The beginnings of the Roman imperial decline seemed less serious in North Africa than elsewhere. However, uprisings did take place. In 238 AD, landowners rebelled unsuccessfully against imperial fiscal policies. Sporadic tribal revolts in the Mauretanian mountains followed from 253 to 288, during the Crisis of the Third Century. The towns also suffered economic difficulties, and building activity almost ceased.[121]

The towns of Roman North Africa had a substantial Jewish population. Some Jews had been deported from Judea or Palestine in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD for rebelling against Roman rule; others had come earlier with Punic settlers. In addition, a number of Berber tribes had converted to Judaism.[122]

Right: an ancient Roman mosaic from Antioch depicting a sub-Saharan African man carrying goods over his shoulder.

Christianity arrived in the 2nd century and soon gained converts in the towns and among slaves. More than eighty bishops, some from distant frontier regions of Numidia, attended the Council of Carthage (256) in 256. By the end of the 4th century, the settled areas had become Christianized, and some Berber tribes had converted en masse.[123]

A division in the church that came to be known as the Donatist heresy began in 313 among Christians in North Africa. The Donatists stressed the holiness of the church and refused to accept the authority to administer the sacraments of those who had surrendered the scriptures when they were forbidden under the Emperor Diocletian (reigned 284–305). The Donatists also opposed the involvement of Constantine the Great (reigned 306–337) in church affairs in contrast to the majority of Christians who welcomed official imperial recognition.[124][125]

The occasionally violent Donatist controversy has been characterized as a struggle between opponents and supporters of the Roman system. The most articulate North African critic of the Donatist position, which came to be called a heresy, was Augustine, bishop of Hippo Regius. Augustine maintained that the unworthiness of a minister did not affect the validity of the sacraments because their true minister was Jesus Christ. In his sermons and books Augustine, who is considered a leading exponent of Christian dogma, evolved a theory of the right of orthodox Christian rulers to use force against schismatics and heretics. Although the dispute was resolved by a decision of an imperial commission in Carthage in 411, Donatist communities continued to exist as late as the 6th century.[126]

A decline in trade weakened Roman control. Independent kingdoms emerged in mountainous and desert areas, towns were overrun, and Berbers, who had previously been pushed to the edges of the Roman Empire, returned.[127]

During the Vandalic War, Belisarius, general of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I based in Constantinople, landed in North Africa in 533 with 16,000 men and within a year destroyed the Vandal Kingdom.[128] Local opposition delayed full Byzantine control of the region for twelve years, however, and when imperial control came, it was but a shadow of the control exercised by Rome. Although an impressive series of fortifications were built, Byzantine rule was compromised by official corruption, incompetence, military weakness, and lack of concern in Constantinople for African affairs, which made it an easy target for the Arabs during the Early Muslim conquests. As a result, many rural areas reverted to Berber rule.[129]

Aksum

The earliest state in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, Dʿmt, dates from around the 8th and 7th centuries BC. D'mt traded through the Red Sea with Egypt and the Mediterranean, providing frankincense. By the 5th and 3rd centuries, D'mt had declined, and several successor states took its place. Later there was greater trade with South Arabia, mainly with the port of Saba. Adulis became an important commercial center in the Ethiopian Highlands. The interaction of the peoples in the two regions, the southern Arabia Sabaeans and the northern Ethiopians, resulted in the Ge'ez culture and language and eventual development of the Ge'ez script. Trade links increased and expanded from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, with Egypt, Israel, Phoenicia, Greece, and Rome, to the Black Sea, and to Persia, India, and China. Aksum was known throughout those lands. By the 5th century BC, the region was very prosperous, exporting ivory, hippopotamus hides, gold dust, spices, and live elephants. It imported silver, gold, olive oil, and wine. Aksum manufactured glass crystal, brass, and copper for export. A powerful Aksum emerged, unifying parts of eastern Sudan, northern Ethiopia (Tigre), and Eritrea. Its kings built stone palatial buildings and were buried under megalithic monuments. By 300 AD, Aksum was minting its own coins in silver and gold.[130]

In 331 AD, King Ezana (320–350 AD) was converted to Miaphysite Christianity which believes in one united divine-human nature of Christ, supposedly by Frumentius and Aedesius, who became stranded on the Red Sea coast. Some scholars believed the process was more complex and gradual than a simple conversion. Around 350, the time Ezana sacked Meroe, the Syrian monastic tradition took root within the Ethiopian church.[131]

In the 6th century Aksum was powerful enough to add Saba on the Arabian peninsula to her empire. At the end of the 6th century, the Sasanian Empire pushed Aksum out of the peninsula. With the spread of Islam through Western Asia and Northern Africa, Aksum's trading networks in the Mediterranean faltered. The Red Sea trade diminished as it was diverted to the Persian Gulf and dominated by Arabs, causing Aksum to decline. By 800 AD, the capital was moved south into the interior highlands, and Aksum was much diminished.[132]

West Africa

In the western Sahel the rise of settled communities occurred largely as a result of the domestication of millet and of sorghum. Archaeology points to sizable urban populations in West Africa beginning in the 2nd millennium BC. Symbiotic trade relations developed before the trans-Saharan trade, in response to the opportunities afforded by north–south diversity in ecosystems across deserts, grasslands, and forests. The agriculturists received salt from the desert nomads. The desert nomads acquired meat and other foods from pastoralists and farmers of the grasslands and from fishermen on the Niger River. The forest-dwellers provided furs and meat.[133]

Dhar Tichitt and Oualata in present-day Mauritania figure prominently among the early urban centers, dated to 2,000 BC. About 500 stone settlements litter the region in the former savannah of the Sahara. Its inhabitants fished and grew millet. It has been found Augustin Holl that the Soninke of the Mandé peoples were likely responsible for constructing such settlements. Around 300 BC the region became more desiccated and the settlements began to decline, most likely relocating to Koumbi Saleh.[134] Architectural evidence and the comparison of pottery styles suggest that Dhar Tichitt was related to the subsequent Ghana Empire. Djenné-Djenno (in present-day Mali) was settled around 300 BC, and the town grew to house a sizable Iron Age population, as evidenced by crowded cemeteries. Living structures were made of sun-dried mud. By 250 BC Djenné-Djenno had become a large, thriving market town.[135][136] Towns similar to that at Djenne-Jeno also developed at the site of Dia, also in Mali along the Niger River, from around 900 BC.[137]

Farther south, in central Nigeria, around 1,500 BC, the Nok culture developed in Jos Plateau.[138] It was a highly centralized community. The Nok people produced lifelike representations in terracotta, including human heads and human figures, elephants, and other animals. By 500 BC they were smelting iron. By 200 AD the Nok culture had vanished. Based on stylistic similarities with the Nok terracottas, the bronze figurines of the Yoruba kingdom of Ife and those of the Bini kingdom of Benin are now believed to be continuations of the traditions of the earlier Nok culture.[139]

Bantu expansion

2 = c. 1500 BC first migrations

2.a = Eastern Bantu,

2.b = Western Bantu

3 = 1000 – 500 BC Urewe nucleus of Eastern Bantu

4 – 7 = southward advance

9 = 500 BC – 0 Congo nucleus

10 = 0 – 1000 CE last phase[140]

The Bantu expansion involved a significant movement of people in African history and in the settling of the continent.[141] People speaking Bantu languages (a branch of the Niger–Congo family) began in the second millennium BC to spread from Cameroon eastward to the Great Lakes region. In the first millennium BC, Bantu languages spread from the Great Lakes to southern and east Africa. One early movement headed south to the upper Zambezi valley in the 2nd century BC. Then Bantu-speakers pushed westward to the savannahs of present-day Angola and eastward into Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe in the 1st century AD. The second thrust from the Great Lakes was eastward, 2,000 years ago, expanding to the Indian Ocean coast, Kenya and Tanzania. The eastern group eventually met the southern migrants from the Great Lakes in Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Both groups continued southward, with eastern groups continuing to Mozambique and reaching Maputo in the 2nd century AD, and expanding as far as Durban.

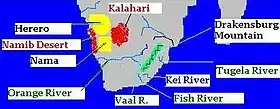

By the later first millennium AD, the expansion had reached the Great Kei River in present-day South Africa. Sorghum, a major Bantu crop, could not thrive under the winter rainfall of Namibia and the western Cape. Khoisan people inhabited the remaining parts of southern Africa.[142]

Medieval and Early Modern (6th to 18th centuries)

Sao civilization

The Sao civilization flourished from about the sixth century BC to as late as the 16th century AD in Central Africa. The Sao lived by the Chari River south of Lake Chad in territory that later became part of present-day Cameroon and Chad. They are the earliest people to have left clear traces of their presence in the territory of modern Cameroon. Today, several ethnic groups of northern Cameroon and southern Chad – but particularly the Sara people – claim descent from the civilization of the Sao. Sao artifacts show that they were skilled workers in bronze, copper, and iron.[143] Finds include bronze sculptures and terracotta statues of human and animal figures, coins, funerary urns, household utensils, jewelry, highly decorated pottery, and spears.[144] The largest Sao archaeological finds have occurred south of Lake Chad.

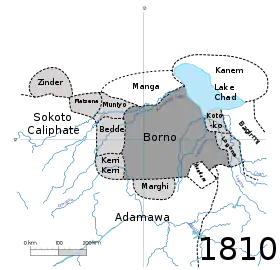

Kanem Empire

The Kanem Empire was centered in the Chad Basin. It was known as the Kanem Empire from the 9th century AD onward and lasted as the independent kingdom of Bornu until 1893. At its height it encompassed an area covering not only much of Chad, but also parts of modern southern Libya, eastern Niger, northeastern Nigeria, northern Cameroon, parts of South Sudan and the Central African Republic. The history of the Empire is mainly known from the Royal Chronicle or Girgam discovered in 1851 by the German traveller Heinrich Barth.[145] Kanem rose in the 8th century in the region to the north and east of Lake Chad. The Kanem empire went into decline, shrank, and in the 14th century was defeated by Bilala invaders from the Lake Fitri region.[146]

Around the 9th century AD, the central Sudanic Empire of Kanem, with its capital at Njimi, was founded by the Kanuri-speaking nomads. Kanem arose by engaging in the trans-Saharan trade. It exchanged slaves captured by raiding the south for horses from North Africa, which in turn aided in the acquisition of slaves. By the late 11th century, the Islamic Sayfawa (Saifawa) dynasty was founded by Humai (Hummay) ibn Salamna. The Sayfawa Dynasty ruled for 771 years, making it one of the longest-lasting dynasties in human history.[147] In addition to trade, taxation of local farms around Kanem became a source of state income. Kanem reached its peak under Mai (king) Dunama Dibalemi ibn Salma (1210–1248). The empire reportedly was able to field 40,000 cavalry, and it extended from Fezzan in the north to the Sao state in the south. Islam became firmly entrenched in the empire. Pilgrimages to Mecca were common; Cairo had hostels set aside specifically for pilgrims from Kanem.[148][149]

Bornu Empire

The Kanuri people led by the Sayfuwa migrated to the west and south of the lake, where they established the Bornu Empire. By the late 16th century the Bornu empire had expanded and recaptured the parts of Kanem that had been conquered by the Bulala.[150] Satellite states of Bornu included the Damagaram in the west and Baguirmi to the southeast of Lake Chad. Around 1400, the Sayfawa Dynasty moved its capital to Bornu, a tributary state southwest of Lake Chad with a new capital Birni Ngarzagamu. Overgrazing had caused the pastures of Kanem to become too dry. In addition, political rivalry from the Bilala clan was becoming intense. Moving to Bornu better situated the empire to exploit the trans-Saharan trade and to widen its network in that trade. Links to the Hausa states were also established, providing horses and salt from Bilma for Bonoman gold.[151] Mai Ali Gazi ibn Dunama (c. 1475 – 1503) defeated the Bilala, reestablishing complete control of Kanem.[152] During the early 16th century, the Sayfawa Dynasty solidified its hold on the Bornu population after much rebellion. In the latter half of the 16th century, Mai Idris Alooma modernized its military, in contrast to the Songhai Empire. Turkish mercenaries were used to train the military. The Sayfawa Dynasty were the first monarchs south of the Sahara to import firearms.[152] The empire controlled all of the Sahel from the borders of Darfur in the east to Hausaland to the west. Friendly relationship was established with the Ottoman Empire via Tripoli. The Mai exchanged gifts with the Ottoman sultan.[153]

During the 17th and 18th centuries, not much is known about Bornu. During the 18th century, it became a center of Islamic learning. However, Bornu's army became outdated by not importing new arms,[151] and Kamembu had also begun its decline. The power of the mai was undermined by droughts and famine that were becoming more intense, internal rebellion in the pastoralist north, growing Hausa power, and the importation of firearms which made warfare more bloody. By 1841, the last mai was deposed, bringing to an end the long-lived Sayfawa Dynasty.[152] In its place, the al-Kanemi dynasty of the shehu rose to power.

Shilluk Kingdom

The Shilluk Kingdom was centered in South Sudan from the 15th century from along a strip of land along the western bank of the White Nile, from Lake No to about 12° north latitude. The capital and royal residence was in the town of Fashoda. The kingdom was founded during the mid-15th century AD by its first ruler, Nyikang. During the 19th century, the Shilluk Kingdom faced decline following military assaults from the Ottoman Empire and later British and Sudanese colonization in Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.[154]

Baguirmi Kingdom

The Kingdom of Baguirmi existed as an independent state during the 16th and 17th centuries southeast of Lake Chad in what is now the country of Chad. Baguirmi emerged to the southeast of the Kanem–Bornu Empire. The kingdom's first ruler was Mbang Birni Besse. Later in his reign, the Bornu Empire conquered the state and made it a tributary.[155]

.jpg.webp)

Wadai Empire

The Wadai Empire was centered on Chad and the Central African Republic from the 17th century. The Tunjur people founded the Wadai Kingdom to the east of Bornu in the 16th century. In the 17th century there was a revolt of the Maba people who established a Muslim dynasty.[156]

At first Wadai paid tribute to Bornu and Durfur, but by the 18th century Wadai was fully independent and had become an aggressor against its neighbors.[75]To the west of Bornu, by the 15th century the Kingdom of Kano had become the most powerful of the Hausa Kingdoms, in an unstable truce with the Kingdom of Katsina to the north.[157] Both were absorbed into the Sokoto Caliphate during the Fulani Jihad of 1805, which threatened Bornu itself.[158]

Luba Empire

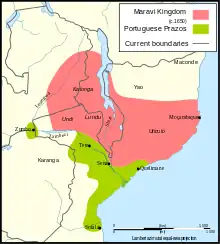

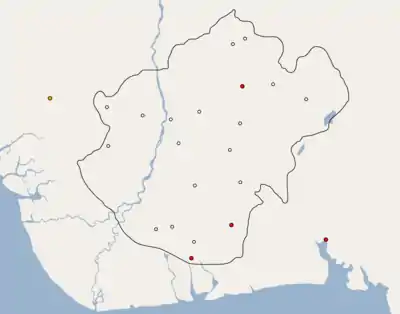

Sometime between 1300 and 1400 AD, Kongolo Mwamba (Nkongolo) from the Balopwe clan unified the various Luba peoples, near Lake Kisale. He founded the Kongolo Dynasty, which was later ousted by Kalala Ilunga. Kalala expanded the kingdom west of Lake Kisale. A new centralized political system of spiritual kings (balopwe) with a court council of head governors and sub-heads all the way to village heads. The balopwe was the direct communicator with the ancestral spirits and chosen by them. Conquered states were integrated into the system and represented in the court, with their titles. The authority of the balopwe resided in his spiritual power rather than his military authority. The army was relatively small. The Luba was able to control regional trade and collect tribute for redistribution. Numerous offshoot states were formed with founders claiming descent from the Luba. The Luba political system spread throughout Central Africa, southern Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and the western Congo. Two major empires claiming Luba descent were the Lunda Empire and Maravi Empire. The Bemba people and Basimba people of northern Zambia were descended from Luba migrants who arrived in Zambia during the 17th century.[159][160]

Lunda Empire

In the 1450s, a Luba from the royal family Ilunga Tshibinda married Lunda queen Rweej and united all Lunda peoples. Their son mulopwe Luseeng expanded the kingdom. His son Naweej expanded the empire further and is known as the first Lunda emperor, with the title mwato yamvo (mwaant yaav, mwant yav), the Lord of Vipers. The Luba political system was retained, and conquered peoples were integrated into the system. The mwato yamvo assigned a cilool or kilolo (royal adviser) and tax collector to each state conquered.[161][162]

Numerous states claimed descent from the Lunda. The Imbangala of inland Angola claimed descent from a founder, Kinguri, brother of Queen Rweej, who could not tolerate the rule of mulopwe Tshibunda. Kinguri became the title of kings of states founded by Queen Rweej's brother. The Luena (Lwena) and Lozi (Luyani) in Zambia also claim descent from Kinguri. During the 17th century, a Lunda chief and warrior called Mwata Kazembe set up an Eastern Lunda kingdom in the valley of the Luapula River. The Lunda's western expansion also saw claims of descent by the Yaka and the Pende. The Lunda linked Central Africa with the western coast trade. The kingdom of Lunda came to an end in the 19th century when it was invaded by the Chokwe, who were armed with guns.[162][163]

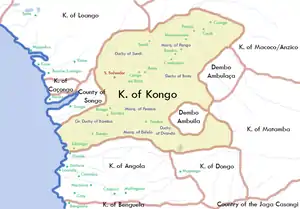

Kingdom of Kongo

By the 15th century AD, the farming Bakongo people (ba being the plural prefix) were unified as the Kingdom of Kongo under a ruler called the manikongo, residing in the fertile Pool Malebo area on the lower Congo River. The capital was M'banza-Kongo. With superior organization, they were able to conquer their neighbors and extract tribute. They were experts in metalwork, pottery, and weaving raffia cloth. They stimulated interregional trade via a tribute system controlled by the manikongo. Later, maize (corn) and cassava (manioc) would be introduced to the region via trade with the Portuguese at their ports at Luanda and Benguela. The maize and cassava would result in population growth in the region and other parts of Africa, replacing millet as a main staple.[164]

By the 16th century, the manikongo held authority from the Atlantic in the west to the Kwango River in the east. Each territory was assigned a mani-mpembe (provincial governor) by the manikongo. In 1506, Afonso I (1506–1542), a Christian, took over the throne. Slave trading increased with Afonso's wars of conquest. About 1568 to 1569, the Jaga invaded Kongo, laying waste to the kingdom and forcing the manikongo into exile. In 1574, Manikongo Álvaro I was reinstated with the help of Portuguese mercenaries. During the latter part of the 1660s, the Portuguese tried to gain control of Kongo. Manikongo António I (1661–1665), with a Kongolese army of 5,000, was destroyed by an army of Afro-Portuguese at the Battle of Mbwila. The empire dissolved into petty polities, fighting among each other for war captives to sell into slavery.[165][166][167]

Kongo gained captives from the Kingdom of Ndongo in wars of conquest. Ndongo was ruled by the ngola. Ndongo would also engage in slave trading with the Portuguese, with São Tomé being a transit point to Brazil. The kingdom was not as welcoming as Kongo; it viewed the Portuguese with great suspicion and as an enemy. The Portuguese in the latter part of the 16th century tried to gain control of Ndongo but were defeated by the Mbundu. Ndongo experienced depopulation from slave raiding. The leaders established another state at Matamba, affiliated with Queen Nzinga, who put up a strong resistance to the Portuguese until coming to terms with them. The Portuguese settled along the coast as trade dealers, not venturing on conquest of the interior. Slavery wreaked havoc in the interior, with states initiating wars of conquest for captives. The Imbangala formed the slave-raiding state of Kasanje, a major source of slaves during the 17th and 18th centuries.[168][169]

Horn of Africa

Somalia

The birth of Islam opposite Somalia's Red Sea coast meant that Somali merchants and sailors living on the Arabian Peninsula gradually came under the influence of the new religion through their converted Arab Muslim trading partners. With the migration of Muslim families from the Islamic world to Somalia in the early centuries of Islam, and the peaceful conversion of the Somali population by Somali Muslim scholars in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic Mogadishu, Berbera, Zeila, Barawa and Merka, which were part of the Berber (the medieval Arab term for the ancestors of the modern Somalis) civilization.[170][171] The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the City of Islam[172] and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.[173]

During this period, sultanates such as the Ajuran Empire and the Sultanate of Mogadishu, and republics like Barawa, Merca and Hobyo and their respective ports flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, India, Venice,[174] Persia, Egypt, Portugal and as far away as China. Vasco da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses four or five stories high and big palaces in its centre, in addition to many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[175]

In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with cloth and spices, for which they in return received gold, wax, and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit in the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[176] Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria),[177] together with Merca and Barawa, served as a transit stop for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[178] Jewish merchants from the Strait of Hormuz brought their Indian textiles and fruit to the Somali coast to exchange for grain and wood.[179]

Trading relations were established with Malacca in the 15th century,[180] with cloth, ambergris, and porcelain being the main commodities of the trade.[181] Giraffes, zebras, and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between the Asia and Africa[182] and influenced the Chinese language with borrowings from the Somali language in the process. Hindu merchants from Surat and southeast African merchants from Pate, seeking to bypass both the Portuguese blockade and Omani meddling, used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were out of the two powers' jurisdiction) to conduct their trade in safety and without any problems.[183]

Ethiopia

The Zagwe dynasty ruled many parts of modern Ethiopia and Eritrea from approximately 1137 to 1270. The name of the dynasty comes from the Cushitic speaking Agaw of northern Ethiopia. From 1270 AD and on for many centuries, the Solomonic dynasty ruled the Ethiopian Empire.[184]

In the early 15th century Ethiopia sought to make diplomatic contact with European kingdoms for the first time since Aksumite times. A letter from King Henry IV of England to the Emperor of Abyssinia survives.[185] In 1428, the Emperor Yeshaq I sent two emissaries to Alfonso V of Aragon, who sent return emissaries who failed to complete the return trip.[186]

The first continuous relations with a European country began in 1508 with the Kingdom of Portugal under Emperor Lebna Dengel, who had just inherited the throne from his father.[187] This proved to be an important development, for when the empire was subjected to the attacks of the Adal general and imam, Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (called "Grañ", or "the Left-handed"), Portugal assisted the Ethiopian emperor by sending weapons and four hundred men, who helped his son Gelawdewos defeat Ahmad and re-establish his rule.[188] This Abyssinian–Adal War was also one of the first proxy wars in the region as the Ottoman Empire, and Portugal took sides in the conflict.

When Emperor Susenyos converted to Roman Catholicism in 1624, years of revolt and civil unrest followed resulting in thousands of deaths.[189] The Jesuit missionaries had offended the Orthodox faith of the local Ethiopians, and on June 25, 1632, Susenyos's son, Emperor Fasilides, declared the state religion to again be Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and expelled the Jesuit missionaries and other Europeans.[190][191]

Maghreb

By 711 AD, the Umayyad Caliphate had conquered all of North Africa. By the 10th century, the majority of the population of North Africa was Muslim.[193]

By the 9th century AD, the unity brought about by the Islamic conquest of North Africa and the expansion of Islamic culture came to an end. Conflict arose as to who should be the successor of the prophet. The Umayyads had initially taken control of the Caliphate, with their capital at Damascus. Later, the Abbasids had taken control, moving the capital to Baghdad. The Berber people, being independent in spirit and hostile to outside interference in their affairs and to Arab exclusivity in orthodox Islam, adopted Shi'ite and Kharijite Islam, both considered unorthodox and hostile to the authority of the Abbasid Caliphate. Numerous Kharijite kingdoms came and fell during the 8th and 9th centuries, asserting their independence from Baghdad. In the early 10th century, Shi'ite groups from Syria, claiming descent from Muhammad's daughter Fatimah, founded the Fatimid Dynasty in the Maghreb. By 950, they had conquered all of the Maghreb and by 969 all of Egypt. They had immediately broken away from Baghdad.[194]

In an attempt to bring about a purer form of Islam among the Sanhaja Berbers, Abdallah ibn Yasin founded the Almoravid movement in present-day Mauritania and Western Sahara. The Sanhaja Berbers, like the Soninke, practiced an indigenous religion alongside Islam. Abdallah ibn Yasin found ready converts in the Lamtuna Sanhaja, who were dominated by the Soninke in the south and the Zenata Berbers in the north. By the 1040s, all of the Lamtuna was converted to the Almoravid movement. With the help of Yahya ibn Umar and his brother Abu Bakr ibn Umar, the sons of the Lamtuna chief, the Almoravids created an empire extending from the Sahel to the Mediterranean. After the death of Abdallah ibn Yassin and Yahya ibn Umar, Abu Bakr split the empire in half, between himself and Yusuf ibn Tashfin, because it was too big to be ruled by one individual. Abu Bakr took the south to continue fighting the Soninke, and Yusuf ibn Tashfin took the north, expanding it to southern Spain. The death of Abu Bakr in 1087 saw a breakdown of unity and increase military dissension in the south. This caused a re-expansion of the Soninke. The Almoravids were once held responsible for bringing down the Ghana Empire in 1076, but this view is no longer credited.[195]

During the 10th through 13th centuries, there was a large-scale movement of bedouins out of the Arabian Peninsula. About 1050, a quarter of a million Arab nomads from Egypt moved into the Maghreb. Those following the northern coast were referred to as Banu Hilal. Those going south of the Atlas Mountains were the Banu Sulaym. This movement spread the use of the Arabic language and hastened the decline of the Berber language and the Arabisation of North Africa. Later an Arabised Berber group, the Hawwara, went south to Nubia via Egypt.[196]

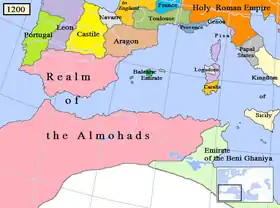

In the 1140s, Abd al-Mu'min declared jihad on the Almoravids, charging them with decadence and corruption. He united the northern Berbers against the Almoravids, overthrowing them and forming the Almohad Empire. During this period, the Maghreb became thoroughly Islamised and saw the spread of literacy, the development of algebra, and the use of the number zero and decimals. By the 13th century, the Almohad states had split into three rival states. Muslim states were largely extinguished in the Iberian Peninsula by the Christian kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, and Portugal. Around 1415, Portugal engaged in a reconquista of North Africa by capturing Ceuta, and in later centuries Spain and Portugal acquired other ports on the North African coast. In 1492, at the end of the Granada War, Spain defeated Muslims in the Emirate of Granada, effectively ending eight centuries of Muslim domination in southern Iberia.[197]

Portugal and Spain took the ports of Tangiers, Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis. This put them in direct competition with the Ottoman Empire, which re-took the ports using Turkish corsairs (pirates and privateers). The Turkish corsairs would use the ports for raiding Christian ships, a major source of booty for the towns. Technically, North Africa was under the control of the Ottoman Empire, but only the coastal towns were fully under Istanbul's control. Tripoli benefited from trade with Borno. The pashas of Tripoli traded horses, firearms, and armor via Fez with the sultans of the Bornu Empire for slaves.[198]

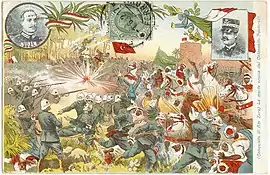

In the 16th century, an Arab nomad tribe that claimed descent from Muhammad's daughter, the Saadis, conquered and united Morocco. They prevented the Ottoman Empire from reaching to the Atlantic and expelled Portugal from Morocco's western coast. Ahmad al-Mansur brought the state to the height of its power. He invaded Songhay in 1591, to control the gold trade, which had been diverted to the western coast of Africa for European ships and to the east, to Tunis. Morocco's hold on Songhay diminished in the 17th century. In 1603, after Ahmad's death, the kingdom split into the two sultanates of Fes and Marrakesh. Later it was reunited by Moulay al-Rashid, founder of the Alaouite Dynasty (1672–1727). His brother and successor, Ismail ibn Sharif (1672–1727), strengthened the unity of the country by importing slaves from the Sudan to build up the military.[199]

Nile Valley

Egypt

In 642 AD, the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Byzantine Egypt.[193]

Egypt under the Fatimid Caliphate was prosperous. Dams and canals were repaired, and wheat, barley, flax, and cotton production increased. Egypt became a major producer of linen and cotton cloth. Its Mediterranean and Red Sea trade increased. Egypt also minted a gold currency called the Fatimid dinar, which was used for international trade. The bulk of revenues came from taxing the fellahin (peasant farmers), and taxes were high. Tax collecting was leased to Berber overlords, who were soldiers who had taken part in the Fatimid conquest in 969 AD. The overlords paid a share to the caliphs and retained what was left. Eventually, they became landlords and constituted a settled land aristocracy.[200]

To fill the military ranks, Mamluk Turkish slave cavalry and Sudanese slave infantry were used. Berber freemen were also recruited. In the 1150s, tax revenues from farms diminished. The soldiers revolted and wreaked havoc in the countryside, slowed trade, and diminished the power and authority of the Fatimid caliphs.[201]

During the 1160s, Fatimid Egypt came under threat from European crusaders. Out of this threat, a Kurdish general named Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb (Saladin), with a small band of professional soldiers, emerged as an outstanding Muslim defender. Saladin defeated the Christian crusaders at Egypt's borders and recaptured Jerusalem in 1187. On the death of Al-Adid, the last Fatimid caliph, in 1171, Saladin became the ruler of Egypt, ushering in the Ayyubid Dynasty. Under his rule, Egypt returned to Sunni Islam, Cairo became an important center of Arab Islamic learning, and Mamluk slaves were increasingly recruited from Turkey and southern Russia for military service. Support for the military was tied to the iqta, a form of land taxation in which soldiers were given ownership in return for military service.[202]

Over time, Mamluk slave soldiers became a very powerful landed aristocracy, to the point of getting rid of the Ayyubid dynasty in 1250 and establishing a Mamluk dynasty. The more powerful Mamluks were referred to as amirs. For 250 years, Mamluks controlled all of Egypt under a military dictatorship. Egypt extended her territories to Syria and Palestine, thwarted the crusaders, and halted a Mongol invasion in 1260 at the Battle of Ain Jalut. Mamluk Egypt came to be viewed as a protector of Islam, and of Medina and Mecca. Eventually the iqta system declined and proved unreliable for providing an adequate military. The Mamluks started viewing their iqta as hereditary and became attuned to urban living. Farm production declined, and dams and canals lapsed into disrepair. Mamluk military skill and technology did not keep pace with new technology of handguns and cannons.[203]

With the rise of the Ottoman Empire, Egypt was easily defeated. In 1517, at the end of an Ottoman–Mamluk War, Egypt became part of the Ottoman Empire. The Istanbul government revived the iqta system. Trade was reestablished in the Red Sea, but it could not completely connect with the Indian Ocean trade because of growing Portuguese presence. During the 17th and 18th centuries, hereditary Mamluks regained power. The leading Mamluks were referred to as beys. Pashas, or viceroys, represented the Istanbul government in name only, operating independently. During the 18th century, dynasties of pashas became established. The government was weak and corrupt.[204]

In 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt. The local forces had little ability to resist the French conquest. However, the British Empire and the Ottoman Empire were able to remove French occupation in 1801. These events marked the beginning of a 19th-century Anglo-Franco rivalry over Egypt.[205]

Sudan

Christian and Islamic Nubia

After Ezana of Aksum sacked Meroe, people associated with the site of Ballana moved into Nubia from the southwest and founded three kingdoms: Makuria, Nobatia, and Alodia. They would rule for 200 years. Makuria was above the third cataract, along the Dongola Reach with its capital at Dongola. Nobadia was to the north with its capital at Faras, and Alodia was to the south with its capital at Soba. Makuria eventually absorbed Nobadia. The people of the region converted to Monophysite Christianity around 500 to 600 CE. The church initially started writing in Coptic, then in Greek, and finally in Old Nubian, a Nilo-Saharan language. The church was aligned with the Egyptian Coptic Church.[206][207]

By 641, Egypt was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate. This effectively blocked Christian Nubia and Aksum from Mediterranean Christendom. In 651–652, Arabs from Egypt invaded Christian Nubia. Nubian archers soundly defeated the invaders. The Baqt (or Bakt) Treaty was drawn, recognizing Christian Nubia and regulating trade. The treaty controlled relations between Christian Nubia and Islamic Egypt for almost six hundred years.[208]

By the 13th century, Christian Nubia began its decline. The authority of the monarchy was diminished by the church and nobility. Arab bedouin tribes began to infiltrate Nubia, causing further havoc. Fakirs (holy men) practicing Sufism introduced Islam into Nubia. By 1366, Nubia had become divided into petty fiefdoms when it was invaded by Mamluks. During the 15th century, Nubia was open to Arab immigration. Arab nomads intermingled with the population and introduced the Arab culture and the Arabic language. By the 16th century, Makuria and Nobadia had been Islamized. During the 16th century, Abdallah Jamma headed an Arab confederation that destroyed Soba, capital of Alodia, the last holdout of Christian Nubia. Later Alodia would fall under the Funj Sultanate.[208]

During the 15th century, Funj herders migrated north to Alodia and occupied it. Between 1504 and 1505, the kingdom expanded, reaching its peak and establishing its capital at Sennar under Badi II Abu Daqn (c. 1644 – 1680). By the end of the 16th century, the Funj had converted to Islam. They pushed their empire westward to Kordofan. They expanded eastward, but were halted by Ethiopia. They controlled Nubia down to the 3rd Cataract. The economy depended on captured enemies to fill the army and on merchants travelling through Sennar. Under Badi IV (1724–1762), the army turned on the king, making him nothing but a figurehead. In 1821, the Funj were conquered by Muhammad Ali (1805–1849), Pasha of Egypt.[209][210]

Southern Africa

Settlements of Bantu-speaking peoples who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen were long already well established south of the Limpopo River by the 4th century CE, displacing and absorbing the original Khoisan speakers. They slowly moved south, and the earliest ironworks in modern-day KwaZulu-Natal Province are believed to date from around 1050. The southernmost group was the Xhosa people, whose language incorporates certain linguistic traits from the earlier Khoi-San people, reaching the Great Fish River in today's Eastern Cape Province.[211]

Great Zimbabwe and Mapungubwe

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe was the first state in Southern Africa, with its capital at Mapungubwe. The state arose in the 12th century CE. Its wealth came from controlling the trade in ivory from the Limpopo Valley, copper from the mountains of northern Transvaal, and gold from the Zimbabwe Plateau between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers, with the Swahili merchants at Chibuene. By the mid-13th century, Mapungubwe was abandoned.[212]

After the decline of Mapungubwe, Great Zimbabwe rose on the Zimbabwe Plateau. Zimbabwe means stone building. Great Zimbabwe was the first city in Southern Africa and was the center of an empire, consolidating lesser Shona polities. Stone building was inherited from Mapungubwe. These building techniques were enhanced and came into maturity at Great Zimbabwe, represented by the wall of the Great Enclosure. The dry-stack stone masonry technology was also used to build smaller compounds in the area. Great Zimbabwe flourished by trading with Swahili Kilwa and Sofala. The rise of Great Zimbabwe parallels the rise of Kilwa. Great Zimbabwe was a major source of gold. Its royal court lived in luxury, wore Indian cotton, surrounded themselves with copper and gold ornaments, and ate on plates from as far away as Persia and China. Around the 1420s and 1430s, Great Zimbabwe was on decline. The city was abandoned by 1450. Some have attributed the decline to the rise of the trading town Ingombe Ilede.[213][214]

A new chapter of Shona history ensued. Nyatsimba Mutota, a northern Shona king of the Karanga, engaged in conquest. He and his son Mutope conquered the Zimbabwe Plateau, going through Mozambique to the east coast, linking the empire to the coastal trade. They called their empire Wilayatu 'l Mu'anamutapah or mwanamutapa (Lord of the Plundered Lands), or the Kingdom of Mutapa. Monomotapa was the Portuguese corruption. They did not build stone structures; the northern Shonas had no traditions of building in stone. After the death of Matope in 1480, the empire split into two small empires: Torwa in the south and Mutapa in the north. The split occurred over rivalry from two Shona lords, Changa and Togwa, with the mwanamutapa line. Changa was able to acquire the south, forming the Kingdom of Butua with its capital at Khami.[214][215]

The Mutapa Empire continued in the north under the mwenemutapa line. During the 16th century the Portuguese were able to establish permanent markets up the Zambezi River in an attempt to gain political and military control of Mutapa. They were partially successful. In 1628, a decisive battle allowed them to put a puppet mwanamutapa named Mavura, who signed treaties that gave favorable mineral export rights to the Portuguese. The Portuguese were successful in destroying the mwanamutapa system of government and undermining trade. By 1667, Mutapa was in decay. Chiefs would not allow digging for gold because of fear of Portuguese theft, and the population declined.[215]

The Kingdom of Butua was ruled by a changamire, a title derived from the founder, Changa. Later it became the Rozwi Empire. The Portuguese tried to gain a foothold but were thrown out of the region in 1693, by Changamire Dombo. The 17th century was a period of peace and prosperity. The Rozwi Empire fell into ruins in the 1830s from invading Nguni from Natal.[215]

Namibia

By 1500 AD, most of southern Africa had established states. In northwestern Namibia, the Ovambo engaged in farming and the Herero engaged in herding. As cattle numbers increased, the Herero moved southward to central Namibia for grazing land. A related group, the Ovambanderu, expanded to Ghanzi in northwestern Botswana. The Nama, a Khoi-speaking, sheep-raising group, moved northward and came into contact with the Herero; this would set the stage for much conflict between the two groups. The expanding Lozi states pushed the Mbukushu, Subiya, and Yei to Botei, Okavango, and Chobe in northern Botswana.[216]

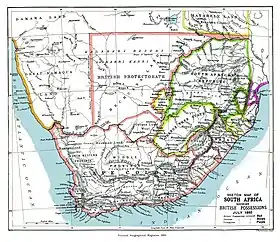

South Africa and Botswana

Sotho–Tswana

The development of Sotho–Tswana states based on the highveld, south of the Limpopo River, began around 1000 CE. The chief's power rested on cattle and his connection to the ancestor. This can be seen in the Toutswemogala Hill settlements with stone foundations and stone walls, north of the highveld and south of the Vaal River. Northwest of the Vaal River developed early Tswana states centered on towns of thousands of people. When disagreements or rivalry arose, different groups moved to form their own states.[217]

Nguni peoples

Southeast of the Drakensberg mountains lived Nguni-speaking peoples (Zulu, Xhosa, Swazi, and Ndebele). They too engaged in state building, with new states developing from rivalry, disagreements, and population pressure causing movement into new regions. This 19th-century process of warfare, state building and migration later became known as the Mfecane (Nguni) or Difaqane (Sotho). Its major catalyst was the consolidation of the Zulu Kingdom.[218] They were metalworkers, cultivators of millet, and cattle herders.[217]

Khoisan and Boers

The Khoisan lived in the southwestern Cape Province, where winter rainfall is plentiful. Earlier Khoisan populations were absorbed by Bantu peoples, such as the Sotho and Nguni, but the Bantu expansion stopped at the region with winter rainfall. Some Bantu languages have incorporated the click consonant of the Khoisan languages. The Khoisan traded with their Bantu neighbors, providing cattle, sheep, and hunted items. In return, their Bantu speaking neighbors traded copper, iron, and tobacco.[217]