Prose Edda

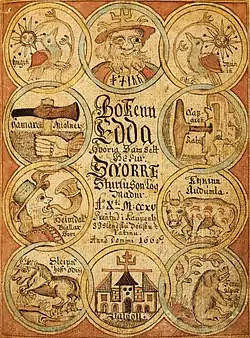

The Prose Edda, also known as the Younger Edda, Snorri's Edda (Icelandic: Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as Edda, is an Old Norse textbook written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been to some extent written, or at least compiled, by the Icelandic scholar, lawspeaker, and historian Snorri Sturluson c. 1220. It is considered the fullest and most detailed source for modern knowledge of Norse mythology, the body of myths of the North Germanic peoples, and draws from a wide variety of sources, including versions of poems that survive into today in a collection known as the Poetic Edda.

| Part of a series on |

| Old Norse |

|---|

|

|

The Prose Edda consists of four sections: The Prologue, a euhemerized account of the Norse gods; Gylfaginning, which provides a question and answer format that details aspects of Norse mythology (consisting of approximately 20,000 words), Skáldskaparmál, which continues this format before providing lists of kennings and heiti (approximately 50,000 words); and Háttatal, which discusses the composition of traditional skaldic poetry (approximately 20,000 words).

Dating from c. 1300 to 1600, seven manuscripts of the Prose Edda differ from one another in notable ways, which provides researchers with independent textual value for analysis. The Prose Edda appears to have functioned similarly to a contemporary textbook, with the goal of assisting Icelandic poets and readers in understanding the subtleties of alliterative verse, and to grasp the meaning behind the many kennings used in skaldic poetry.

Originally known to scholars simply as Edda, the Prose Edda gained its contemporary name in order to differentiate it from the Poetic Edda. Early scholars of the Prose Edda suspected that there once existed a collection of entire poems, a theory confirmed with the rediscovery of manuscripts of the Poetic Edda.[1]

Naming

The etymology of "Edda" remains uncertain; there are many hypotheses about its meaning and developing, yet little agreement. Some argue that the word derives from the name of Oddi, a town in the south of Iceland where Snorri was raised. Edda could therefore mean "book of Oddi." However, this assumption is generally rejected. Anthony Faulkes in his English translation of the Prose Edda comments that this is "unlikely, both in terms of linguistics and history"[2] since Snorri was no longer living at Oddi when he composed his work.

Another connection was made with the word óðr, which means 'poetry or inspiration' in Old Norse.[2] According to Faulkes, though such a connection is plausible semantically, it is unlikely that "Edda" could have been coined in the 13th century on the basis of "óðr", because such a development "would have had to have taken place gradually", and Edda in the sense of 'poetics' is not likely to have existed in the preliterary period.[3]

Edda also means 'great-grandparent', a word that appears in Skáldskaparmál, which occurs as the name of a figure in the eddic poem Rigsthula and in other medieval texts.

A final hypothesis is derived from the Latin edo, meaning "I write". It relies on the fact that the word "kredda" (meaning "belief") is certified and comes from the Latin "credo", meaning 'I believe'. Edda in this case could be translated as "Poetic Art". This is the meaning that the word was then given in the medieval period.[2]

The now uncommonly used name Sæmundar Edda was given by the Bishop Brynjólfur Sveinsson to the collection of poems contained in the Codex Regius, many of which are quoted by Snorri. Brynjólfur, along with many others of his time incorrectly believed that they were collected by Sæmundr fróði[4] (therefore before the drafting of the Edda of Snorri), and so the Poetic Edda is also known as the Elder Edda.

Manuscripts

Seven manuscripts of the Prose Edda have survived into the present day: Six copies from the medieval period and another dating to the 1600s. No one manuscript is complete, and each has variations. In addition to three fragments, the four main manuscripts are Codex Regius, Codex Wormianus, Codex Trajectinus, and the Codex Upsaliensis:[5]

| Name | Current location | Dating | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codex Upsaliensis (DG 11) | University of Uppsala library, Sweden | First quarter of the 14th century.[6] | Provides some variants not found in any of the three other major manuscripts, such as the name Gylfaginning. |

| Codex Regius (GKS 2367 4°) | Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies, Reykjavík, Iceland | First half of the 14th century.[6] | It is the most comprehensive of the four manuscripts, and is received by scholars to be closest to an original manuscript. This is why it is the basis for editions and translations of the Prose Edda. Its name is derived from its conservation in the Royal Library of Denmark for several centuries. From 1973 to 1997, hundreds of ancient Icelandic manuscripts were returned from Denmark to Iceland, including, in 1985, the Codex Regius, which is now preserved by the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. |

| Codex Wormianus (AM 242 fol) | Arnamagnæan Manuscript Collection, Copenhagen, Denmark | Mid-14th century.[6] | None |

| Codex Trajectinus (MSS 1374) | University of Utrecht library, Netherlands | Written c. 1600.[6] | A copy of a manuscript that was made in the second half of the 13th century. |

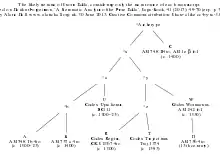

The other three manuscripts are AM 748; AM 757 a 4to; and AM 738 II 4to, AM le ß fol. Although some scholars have doubted whether a sound stemma of the manuscripts can be created, due to the possibility of scribes drawing on multiple exemplars or from memory, recent work has found that the main sources of each manuscript can be fairly readily ascertained.[8] The Prose Edda' remained fairly unknown outside of Iceland until the publication of the Edda Islandorum in 1665.[9]

Authorship

The text is often assumed to have been written or at least compiled to some extent by Snorri Sturluson. This identification is largely based on the following paragraph from a portion of Codex Upsaliensis, an early 14th-century manuscript containing the Edda:

Bók þessi heitir Edda. Hana hefir saman setta Snorri Sturluson eptir þeim hætti sem hér er skipat. Er fyrst frá Ásum ok Ymi, þar næst Skáldskaparmál ok heiti margra hluta, síðast Háttatal er Snorri hefir ort um Hákon konung ok Skúla hertuga.[10] |

This book is called Edda. Snorri Sturluson has compiled it in the manner in which it is arranged here. There is first told about the Æsir and Ymir, then Skáldskaparmál (‘poetic diction’) and (poetical) names of many things, finally Háttatal (‘enumeration of metres or verse-forms’) which Snorri has composed about King Hákon and Earl Skúli.[10] |

Scholars have noted that this attribution, along with that of other primary manuscripts, is not clear whether or not Snorri is more than the compiler of the work and the author of Háttatal or if he is the author of the entire Edda.[11] Faulkes summarizes the matter of scholarly discourse around the authorship of the Prose Edda as follows:

- Snorri’s authorship of the Prose Edda was upheld by the renaissance scholar Arngrímur Jónsson (1568–1648), and since his time it has generally been accepted without question. But the surviving manuscripts, which were all written more than half a century after Snorri’s death, differ from each other considerably and it is not likely that any of them preserves the work quite as he wrote it. A number of passages in Skáldskaparmál especially have been thought to be interpolations, and this section of the work has clearly been subject to various kinds of revision in most manuscripts. It has also been argued that the prologue and the first paragraph and part of the last paragraph of Gylfaginning are not by Snorri, at least in their surviving forms.[12]

Whatever the case, the mention of Snorri in the manuscripts has been influential in a common acceptance of Snorri as the author or at least one of the authors of the Edda.[11]

Contents

Prologue

The Prologue is the first section of four books of the Prose Edda, consisting of a euhemerized Christian account of the origins of Norse mythology: the Nordic gods are described as human Trojan warriors who left Troy after the fall of that city (an origin similar to the one chosen by Geoffrey of Monmouth in the 12th century to account for the ancestry of the British nation, and which parallels Virgil's Aeneid). According to the Prose Edda, these warriors settled in northern Europe, where they were accepted as divine kings because of their superior culture and technology. Remembrance ceremonies later conducted at their burial sites degenerated into heathen cults, turning them into gods.

Gylfaginning

Gylfaginning (Old Icelandic 'the tricking of Gylfi')[13] follows the Prologue in the Prose Edda. Gylfaginning deals with the creation and destruction of the world of the Nordic gods, and many other aspects of Norse mythology. The section is written in prose interspersed with quotes from eddic poetry.

Skáldskaparmál

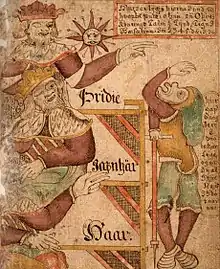

Skáldskaparmál (Old Icelandic 'the language of poetry'[14]) is the third section of Edda, and consists of a dialogue between Ægir, a jötunn who is one of various personifications of the sea, and Bragi, a skaldic god, in which both Norse mythology and discourse on the nature of poetry are intertwined. The origin of a number of kennings are given and Bragi then delivers a systematic list of kennings for various people, places, and things. Bragi then goes on to discuss poetic language in some detail, in particular heiti, the concept of poetical words which are non-periphrastic, for example "steed" for "horse", and again systematises these. This section contains numerous quotes from skaldic poetry.

Háttatal

Háttatal (Old Icelandic "list of verse-forms"[15]) is the last section of Prose Edda. The section is composed by the Icelandic poet, politician, and historian Snorri Sturluson. Primarily using his own compositions, it exemplifies the types of verse forms used in Old Norse poetry. Snorri took a prescriptive as well as descriptive approach; he has systematized the material, often noting that the older poets did not always follow his rules.

Translations

The Prose Edda has been the subject of numerous translations:

- Cnattingius, Andreas Jacobus, ed. (1819), Snorre Sturlesons Edda samt Skalda [Snorre Sturleson's Edda and Skalda] (in Swedish)

- Dasent, George Webbe, ed. (1842), The Prose or Younger Edda commonly ascribed to Snorri Sturluson, Norstedt and Sons

- Egilsson, Sveinbjörn; Sigurðsson, Jón; Jónsson, Finnur (eds.), Edda Snorra Sturlusonar - Edda Snorronis Sturlaei (in Latin) , 3 volumes

- Tomus Primus - Formali, Gylfaginning, Bragaraedur, Skaldskarparmal et Hattatal, 1848

- Tomus Secundus - Tractatus Philologicos et Additamenta ex Codicibus Manuscripts, 1852

- Tomus Tertius - Praefationem, Commmentarios in Carmina, Skaldatal cum Commentario, Indicem Generalem, Legatus Arnamagnæani, 1880–1887

- Wilken, Ernst (ed.), Die prosaische Edda im Auszuge nebst Vǫlsunga-saga und Nornagests-þáttr [The Prose Edda in excerpt along with Völsunga saga and Norna-Gests þáttr], Bibliothek der ältesten deutschen Literatur-Denkmäler. XI. Band (in German)

- Teil I: Text, Paderborn F. Schöningh, 1912 [1877]

- Teil II: Glossar, Paderborn F. Schöningh, 1913 [1877]

- Anderson, Rasmus B., ed. (1880), The Younger Edda, Also Called Snorre's Edda, or the Prose Edda: An English Version of the Foreword; the Fooling of Gylfe, the Afterword; Brage's Talk, the Afterword to Brage's Talk, and the Important Passages in the Poetical Diction (Skáldskaparmál), with an Introduction, Notes, Vocabulary, and Index, Chicago: Griggs , e-text via www.gutenberg.org (1901 ed.)

- Thorpe, Benjamin; Blackwell, I. A., eds. (1906), The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson; and the Younger Eddas of Snorre Sturleson [16]

- Brodeur, Arthur Gilchrist, ed. (1916), "The Prose Edda", Scandinavian classics, New York: American-Scandinavian Foundation, vol. 5

- Grape, Anders, ed. (1977), Snorre Sturlusons Edda: Uppsala-Handskriften DH II (in Icelandic), OCLC 2915588 , 2 volumes : 1 facsimile; 2 translation and notes

- Grape, Anders; Kallstenius, Gottfrid; Thorell, Olod, eds. (1977), Snorre Sturlusons Edda: Uppsala-Handskriften DH II (in Swedish), OCLC 774703003 , 2 volumes : 1 facsimile; 2 translation and notes

- Lerate, Luis, ed. (1984), Edda Menor [Younger Edda] (in Spanish), Alianza Editorial, ISBN 978-84-206-3142-4

- Dillmann, François-Xavier, ed. (1991), "L'Edda: Récits de mythologie nordique" [The Edda : Stories of Norse Myth], L'Aube des peuples (in French), Gallimard, ISBN 2-07-072114-0

- Faulkes, Anthony, ed. (1995), Edda (PDF), Everyman, ISBN 9780460876162

- Byock, Jesse, ed. (2006), The Prose Edda, Penguin Classics, ISBN 0-14-044755-5

- Pálsson, Heimir; Faulkes, Anthony, eds. (2012), Snorri Sturluson: The Uppsala Edda, DG 11 4to (PDF), London: The Viking Society for Northern Research, ISBN 978-0-903521-85-7 , norse with English translation

Editions

- Egilsson, Sveinbjörn, ed. (1848), Edda Snorra Sturlusonar: eða Gylfaginníng, Skáldskaparmál og Háttatal, Prentuð i prentsmiðjulandsins, af prentara H. Helgasyni

- Jónsson, Guðni, ed. (1935), Edda Snorra Sturlusonar: með skáldatali (in Icelandic), Reykjavík: S. Kristjánsson

- Faulkes, Anthony (ed.), Edda , Norse text and English notes

- Snorri Sturluson (2005) [1982], Prologue and Gylfaginning (PDF) (2nd ed.), ISBN 978-0-903521-64-2

- Snorri Sturluson (1998), Skáldskaparmál 1: Introduction, text and notes (PDF), ISBN 978-0-903521-36-9

- Snorri Sturluson (1998), Skáldskaparmál 2: Glossary and index of names (PDF), ISBN 978-0-903521-38-3

- Snorri Sturluson (2007) [1991], Háttatal (PDF) (2nd ed.), ISBN 978-0-903521-68-0

See also

- Edda

- Saga

- Heimskringla

Notes

- Faulkes (1982: XI).

- Faulkes (1982).

- Faulkes (1977: 32-39).

- Gísli (1999: xiii).

- Wanner (2008: 97).

- Ross (2011:151).

- Based on Haukur (2017: 49–70, esp. p.58)

- Haukur (2017:49–70).

- Gylfi (2019: 73-86).

- Faulkes 2005:XIII.

- Byock (2006: XII).

- Faulkes (2005: XIV).

- Faulkes (1982: 7).

- Faulkes (1982: 59).

- Faulkes (1982: 165).

- Both translations were made earlier and then combined into a single text

References

- Faulkes, Anthony. 1977. "Edda", Gripla II, Reykjavík . Online. Last accessed August 12, 2020.

- Faulkes, Anthony. Trans. 1982. Edda. Oxford University Press.

- Faulkes, Anthony. 2005. Edda: Prologue and Gylfaginning. Viking Society for Northern Research. Online. Last accessed August 12, 2020.

- Gísli Sigurðsson. 1999. "Eddukvæði". Mál og menning. ISBN 9979-3-1917-8.

- Gylfi Gunnlaugsson. 2019. "Norse Myths, Nordic Identities: The Divergent Case of Icelandic Romanticism" in Simon Halik (editor). Northern Myths, Modern Identities, 73–86. ISBN 9789004398436_006

- Haukur Þorgeirsson. 2017. "A Stemmic Analysis of the 'Prose Edda'". Saga-Book, 41. Online. Last accessed August 12, 2020.

- Ross, Margaret Clunies. 2011. A History of Old Norse Poetry and Poetics. DS Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-279-8

- Wanner, Kevin J. 2008. Snorri Sturluson and the Edda: The Conversion of Cultural Capital in Medieval Scandinavia. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9801-6

External links

- Hopkins, Joseph S. 2019. "Edda to English: A Survey of English Language Translations of the Prose Edda" at Mimisbrunnr.info

- The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson; and the Younger Eddas of Snorre Sturleson at Project Gutenberg (plain text, HTML and other)

- Langeslag, Paul Sander. Undated. "Old Norse editions" at Septentrionalia.net