Protected cruiser

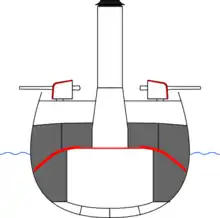

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers resembled armored cruisers, which had in addition a belt of armour along the sides.

Evolution

From the late 1850s, navies began to replace their fleets of wooden ships-of-the-line with armoured ironclad warships. However, the frigates and sloops which performed the missions of scouting, commerce raiding and trade protection remained unarmoured. For several decades, it proved difficult to design a ship which had a meaningful amount of protective armour but at the same time maintained the speed and range required of a "cruising warship". The first attempts to do so, armored cruisers like HMS Shannon, proved unsatisfactory, generally lacking enough speed for their cruiser role.

During the 1870s the increasing power of armour-piercing shells made armouring the sides of a ship more and more difficult, as very thick, heavy armour plates were required. Even if armour dominated the design of the ship, it was likely that the next generation of shells would be able to pierce such armour. The alternative was to leave the sides of the ship vulnerable, but to armour a deck just below the waterline. Since this deck would be struck only very obliquely by shells, it could be less thick and heavy than belt armour. The ship could be designed so that the engines, boilers and magazines were under the armoured deck, and with enough displacement to keep the ship afloat and stable even in the event of damage.[1] Cruisers with armoured decks and no side armour became known as "protected cruisers", and eclipsed the armoured cruisers in popularity in the 1880s and into the 1890s.[2]

HMS Shannon was the first warship to incorporate an armoured deck; hers stretched forward from the armoured citadel to the bow. However, Shannon principally relied on her vertical citadel armour for protection. By the end of the 1870s ships could be found with full-length armoured decks and little or no side armour. The Italian Italia class of very fast battleships had armoured decks and guns but no side armour. The British used a full-length armoured deck in their Comus class of corvettes started in 1878; however the Comus class were designed for colonial service and were capable of only a 13-knot (24 km/h; 15 mph) speed, not fast enough for commerce protection or for fleet duties.

But even while the Comus class were building the four ship Leander-class cruisers. Ordered in 1880 and rated as second-class cruisers, these ships combined the speed of the Iris-class dispatch vessels with a heavy armament, reduced rig and armoured deck. "Leander and her three sisters were very successful and may be seen as the ancestors of most [Royal Navy] cruisers for the rest of the century and beyond. Their general configuration was scaled up to the big First Class cruisers and down to the torpedo cruisers, whilst traces of the protected deck scheme can even be recognised in some sloops."[3]

He believed the Esmeralda was the swiftest and most powerfully-armed cruiser in the world. Happily ... she had passed into the hands of a nation which is never likely to be at war with England, for he could conceive no more terrible scourge for our commerce than she would be in the hands of an enemy. No cruiser in the British navy was swift enough to catch her or strong enough to take her. We have seen what the Alabama could do ... what might we expect from such an incomparably superior vessel as the Esmeralda[?]

Summary of remarks by William Armstrong published in Valparaiso's The Record[4]

The breakthrough in protected-cruiser design came with the Chilean cruiser Esmeralda, designed and built by the British firm Armstrong at their Elswick yard. Esmeralda had a high speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) (dispensing entirely with sails), and an armament of two 10-inch (254 mm) and six 6-inch (152 mm) guns. Her protection scheme, inspired by the Italia class, included a full-length protected deck up to 2 inches (51 mm) thick, and a cork-filled cofferdam along her sides. Esmeralda set the tone for cruiser construction for the years to come, with "Elswick cruisers" on a similar design being constructed for Italy, China, Japan, Argentina, Austria and the United States.[5]

The French Navy adopted the protected-cruiser concept wholeheartedly in the 1880s. The Jeune École school of thought, which proposed a navy composed of fast cruisers for commerce raiding and torpedo boats for coastal defence, became particularly influential in France. The first French protected cruiser was Sfax, laid down in 1882, and followed by six classes of protected cruiser – and no armoured cruisers.

The Royal Navy remained equivocal about which protection scheme to use until 1887. The large Imperieuse class, begun in 1881 and finished in 1886, were built as armoured cruisers but were often referred to as protected cruisers. While they carried an armoured belt some covered only 140 feet (43 m) of the 315-foot (96 m) length of the ship, and the belt was also submerged below the waterline at full load. The real protection of the class came from the armoured deck 4 inches (100 mm) thick, and the arrangement of coal bunkers to prevent flooding. These ships were also the last armoured cruisers to be designed with sails. However, on trials it became clear that the masts and sails did more harm than good. The masts, sails and rigging were removed and replaced with a single military mast with machine-guns.[6]

The next class of small cruisers in the Royal Navy, the Mersey class of 1883, were protected cruisers, but the Royal Navy returned to the armoured cruiser with the Orlando class, begun in 1885 and completed in 1889. However, in 1887 an assessment of the Orlando type judged them inferior to the protected cruisers[7] and thereafter the Royal Navy built only protected cruisers, even for very large first-class cruiser designs, returning to armoured cruisers only in the late 1890s with the Cressy class, laid down in 1898.

The sole major naval power to retain a preference for armoured cruisers during the 1880s was Russia. The Imperial Russian Navy laid down four armoured cruisers and one protected cruiser during the decade, all large ships with sails.[8]

Around 1910, armour plating began to increase in quality and steam-turbine engines, lighter and more powerful than previous reciprocating engines, came into use. Existing protected cruisers became obsolete as they were slower and less well protected than new ships. Oil-fired boilers were introduced, making side bunkers of coal unnecessary but losing the protection they afforded. Protected cruisers were replaced by "light armoured cruisers" with a side armoured belt and armoured decks instead of the single deck, later developed into heavy cruisers.

Protected cruisers in service

Austria-Hungary

The Austro-Hungarian Navy built and operated two classes of protected cruisers. These were two ships of the Kaiser Franz Joseph I class and three of the Zenta class.

Britain

The Royal Navy rated cruisers as first, second and third class between the late 1880s and 1905, and built large numbers of them for trade protection requirements. For most of this time these cruisers were built with a "protected", rather than armoured, scheme of protection for their hulls. First class protected cruisers were as large and as well-armed as armoured cruisers, and were built as an alternative to the large first class armoured cruiser from the late 1880s till 1898. Second class protected cruisers were smaller, displacing 3,000–5,500 long tons (3,000–5,600 t) and were of value both in trade protection duties and scouting for the fleet. Third class cruisers were smaller, lacked a watertight double bottom, and were intended primarily for trade protection duties, though a few small cruisers were built for fleet scout roles or as "torpedo" cruisers during the "protected" era.

The introduction of Krupp armour in six inch thickness rendered the "armoured" protection scheme more effective for the largest first class cruisers, and no large first class protected cruisers were built after 1898. The smaller cruisers, unable to bear the weight of heavy armoured belts retained the "protected" scheme up to 1905, when the last units of the Challenger and Highflyer classes were completed. There was a general hiatus in British cruiser production after this time, apart from a few classes of small, fast scout cruisers for fleet duties. When the Royal Navy began building larger cruisers (less than 4,000 long tons, 4,100 t) again around 1910, they used a mix of armoured decks and/or armoured belts for protection, depending on class. These modern, turbine powered cruisers are properly classified as light cruisers.

France

The French Navy built and operated a series large variety of protected cruisers classes starting with Sfax in 1882. The last ship built to this design was Jurien de la Gravière in 1897.

Germany

The German Imperial Navy (Kaiserliche Marine) built a series of protected cruisers in the 1880s and 1890s, starting with the two ships of the Irene class in the 1880s. The Navy completed only two additional classes of protected cruisers, comprising six more ships: the unique Kaiserin Augusta, and the five Victoria Louise-class ships. The type then was superseded by the armored cruiser at the turn of the century, the first of which being Fürst Bismarck. All of these ships tended to incorporate design elements from their foreign contemporaries, though the Victoria Louise class more closely resembled German battleships of the period, which carried lighter main guns and a greater number of secondary guns.[9]

These ships were employed as fleet scouts and colonial cruisers.[10] Several of the ships served with the German East Asia Squadron, and Hertha, Irene, and Hansa took part in the Battle of Taku Forts in 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion.[11] During a deployment to American waters in 1902, Vineta participated in the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903, where she bombarded Fort San Carlos.[12] Long since obsolete by the outbreak of World War I, the five Victoria Louise-class vessels briefly served as training ships in the Baltic but were withdrawn by the end of 1914 for secondary duties. Kaiserin Augusta and the two Irene-class cruisers similarly served in reduced capacities for the duration of the war. All eight ships were broken up for scrap following Germany's defeat.[10]

Italy

The Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) ordered twenty protected cruisers between the 1880s and 1910s. The first five ships, Giovanni Bausan and the Etna class, were built as "battleship destroyers", armed with a pair of large caliber guns. Subsequent cruisers were more traditional designs, and were instead intended for reconnaissance and colonial duties. Some of the ships, like Calabria and the Campania class, were designed specifically for service in Italy's colonial empire, while others, like Quarto and the Nino Bixio class, were designed as high speed fleet scouts.

Most of these ships saw action during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912, where several of them supported Italian troops fighting in Libya, and another group operated in the Red Sea. There, the cruiser Piemonte and two destroyers sank or destroyed seven Ottoman gunboats in the Battle of Kunfuda Bay in January 1912. Most of the earlier cruisers were obsolescent by the outbreak of World War I, and so had either been sold for scrap or reduced to subsidiary roles. The most modern vessels, including Quarto and the Nino Bixio class, saw limited action in the Adriatic Sea after Italy entered the war in 1915. The surviving vessels continued on in service through the 1920s, with some—Quarto, Campania, and Libia, remaining on active duty into the late 1930s.

The Netherlands

.jpg.webp)

The Royal Netherlands Navy built several protected cruisers between 1880 and 1900.[13] The first protected cruiser was launched in 1890 and called HNLMS Sumatra. It was a small cruiser with a heavy main gun; four years later a larger and more heavily armed protected cruiser was commissioned, which was called HNLMS Koningin Wilhelmina der Nederlanden. In addition to these two cruisers, the Dutch also built six protected cruisers of the Holland class. The Holland-class cruisers were commissioned between 1898 and 1901, and featured, besides other armaments, two 15 cm SK L/40 single naval guns.

The Dutch protected cruisers have played a role in several international events. For example, during the Boxer Rebellion two protected cruisers (Holland and Koningin Wilhelmina der Nederlanden) were sent to Shanghai to protect European citizens and defend Dutch interests.[14][15]

Russia

The Imperial Russian Navy operated a series of protected cruisers classes (Russian: Бронепалубный крейсер, Armored deck cruiser). The last ships built to this design where the Izumrud class in 1901.

Spain

The Spanish Navy operated a series of protected cruisers classes starting with Reina Regente class. The last ship built to this design was Reina Regente in 1899.

United States

._Port_bow%252C_1891_-_NARA_-_512894.jpg.webp)

The first protected cruiser of the United States Navy's "New Navy" was USS Atlanta,[16] launched in October 1884, soon followed by USS Boston in December, and USS Chicago a year later. A numbered series of cruisers began with Newark (Cruiser No. 1), although Charleston (Cruiser No. 2) was the first to be launched, in July 1888, and ending with another Charleston, Cruiser No. 22, launched in 1904. The last survivor of this series is USS Olympia, preserved as a museum ship in Philadelphia.

The reclassification of 17 July 1920 put an end to the U.S. usage of the term "protected cruiser", the existing ships were classified as light or heavy cruisers with new numbers, depending on their level of armor.[16]

Surviving examples

A few protected cruisers have survived as museum ships, while others were used as breakwaters, some of which can still be seen today.

- Aurora – St Petersburg, Russia

- USS Olympia – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Chinese cruiser Zhiyuan replica is on display in Dandong, China

- Bow section and bridge of Puglia – La Spezia, Italy

- Bow section of HMS Vindictive is on display at Ostend, Belgium

- The hulk of USS Charleston serves as a breakwater in Kelsey Bay, on the north coast of Vancouver Island.

See also

- Battlecruiser

- Unprotected cruiser

Footnotes

- Beeler, pp. 42–44

- Parkinson, p. 149

- Brown, Warrior to Dreadnought, Warship Development 1860–1905, page 111.

- "The 'Esmeralda,'" The Record (Valparaiso) 13, no. 183 (4 December 1884): 5.

- Roberts, p. 107

- Parkes, pp. 309–312

- Parkinson, p. 151

- Roberts, p. 109

- Gardiner, pp. 249–254

- Gröner, pp. 47–53, 95

- Perry, p. 29

- "German Commander Blames Venezuelans; Commodore Scheder Says That Fort San Carlos Fired First". The New York Times. 23 January 1903.

- Kimenai, Peter (5 August 2012). "Nederlandse pantser – en pantserdekschepen". p. 3.

- Ministerie van Buitenlandsche Zaken. Diplomatieke bescheiden – behoorende bij de Staatsbegroting voor het dienstjaar 1901, p. 11.

- Nordholt, J. W. Schulte; van Arkel, D., eds. (1970). Acta historiae Neerlandica: Historical studies in the Netherlands. Vol. IV. Brill Publishers. pp. 160–161, 163–164.

- Early American cruisers from the Naval Historical Center. Excluding the larger armored cruiser type, these warships were "protected cruisers", with a steel armored deck covering machinery and ammunition magazines.

References

- Beeler, John, Birth of the Battleship: British Capital Ship Design 1870–1881. Caxton, London, 2003. ISBN 1-84067-534-9

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships 1815–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-790-9.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships. first published Seeley Service & Co, 1957, published United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Perry, Michael (2001). Peking 1900: the Boxer Rebellion. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-181-7.

- Parkinson, Roger (2008). The late Victorian Navy: the pre-dreadnought era and the origins of the First World War. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-372-7.