Aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft.[1] Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a naval force to project air power worldwide without depending on local bases for staging aircraft operations. Carriers have evolved since their inception in the early twentieth century from wooden vessels used to deploy balloons to nuclear-powered warships that carry numerous fighters, strike aircraft, helicopters, and other types of aircraft. While heavier aircraft such as fixed-wing gunships and bombers have been launched from aircraft carriers, these aircraft have not successfully landed on a carrier. By its diplomatic and tactical power, its mobility, its autonomy and the variety of its means, the aircraft carrier is often the centerpiece of modern combat fleets. Tactically or even strategically, it replaced the battleship in the role of flagship of a fleet. One of its great advantages is that, by sailing in international waters, it does not interfere with any territorial sovereignty and thus obviates the need for overflight authorizations from third-party countries, reduces the times and transit distances of aircraft and therefore significantly increase the time of availability on the combat zone.

There is no single definition of an "aircraft carrier",[2] and modern navies use several variants of the type. These variants are sometimes categorized as sub-types of aircraft carriers,[3] and sometimes as distinct types of naval aviation-capable ships.[2][4] Aircraft carriers may be classified according to the type of aircraft they carry and their operational assignments. Admiral Sir Mark Stanhope, RN, former First Sea Lord (head) of the Royal Navy, has said, "To put it simply, countries that aspire to strategic international influence have aircraft carriers."[5] Henry Kissinger, while United States Secretary of State, also said: "An aircraft carrier is 100,000 tons of diplomacy."[6]

As of October 2022, there are 47 active aircraft carriers in the world operated by fourteen navies. The United States Navy has 11 large nuclear-powered fleet carriers—carrying around 80 fighters each—the largest carriers in the world; the total combined deck space is over twice that of all other nations combined.[7] As well as the aircraft carrier fleet, the US Navy has nine amphibious assault ships used primarily for helicopters, although these also each carry up to 20 vertical or short take-off and landing (V/STOL) fighter jets and are similar in size to medium-sized fleet carriers. The United Kingdom, China and India each operate two aircraft carriers. France and Russia each operate a single aircraft carrier with a capacity of 30 to 60 fighter jets. Italy operates two light V/STOL carriers and Spain operates one V/STOL aircraft-carrying assault ship. Helicopter carriers are operated by Japan (4, two of which are being converted to operate V/STOL fighters), France (3), Australia (2), Egypt (2), South Korea (2), China (2), Thailand (1) and Brazil (1). Future aircraft carriers are under construction or in planning by India, France, Russia, South Korea, Turkey and the US.

Types of carriers

%252CFS_Charles_De_Gaulle_(R-92)%252CFS_Cassard_(D-614)%252C_guided_missile_cruiser_USS_Vicksburg_(CG_69)%252C_USS_McCampbell_(DDG_85)_conduct_joint_operations_in_the_Persian_Gulf.jpg.webp)

General features

- Speed is an important asset for aircraft carriers, as they need to be deployed anywhere in the world quickly, and must be fast enough to evade detection and targeting by enemy forces. High speed provides additional "wind over the deck," increasing the lift available for fixed-wing aircraft to carry fuel and munitions. To avoid nuclear submarines, they should be faster than 30 knots.

- Aircraft carriers are among the largest warships, as much deck room is needed.

- An aircraft carrier must be able to perform increasingly diverse mission sets. Diplomacy, power projection, quick crisis response force, land attack from the sea, sea base for helicopter and amphibious assault forces, anti-surface warfare (ASUW), Defensive Counter Air (DCA), and humanitarian aid disaster relief (HADR) are some of the missions the aircraft carrier is expected to accomplish. Traditionally an aircraft carrier is supposed to be one ship that can perform at least power projection and sea control missions.[8]

- An aircraft carrier must be able to efficiently operate an air combat group. This means it should handle fixed-wing jets as well as helicopters. This includes ships designed to support operations of short-takeoff/vertical-landing (STOVL) jets.

Basic types

- Aircraft cruiser

- Amphibious assault ship and sub-types

- Anti-submarine warfare carrier

- Balloon carrier and balloon tenders

- Escort carrier

- Fleet carrier

- Flight deck cruiser

- Helicopter carrier

- Light aircraft carrier

- Sea Control Ship

- Seaplane tender and seaplane carriers

Some of the types listed here are not strictly defined as aircraft carriers by some sources.

By role

_underway_in_the_Atlantic_Ocean_on_30_January_2019_(190130-N-PW716-1312).JPG.webp)

A fleet carrier is intended to operate with the main fleet and usually provides an offensive capability. These are the largest carriers capable of fast speeds. By comparison, escort carriers were developed to provide defense for convoys of ships. They were smaller and slower with lower numbers of aircraft carried. Most were built from mercantile hulls or, in the case of merchant aircraft carriers, were bulk cargo ships with a flight deck added on top. Light aircraft carriers were fast enough to operate with the main fleet but of smaller size with reduced aircraft capacity.

The Soviet aircraft carrier Admiral Kusnetsov was termed a "heavy aircraft-carrying cruiser". This was primarily a legal construct to avoid the limitations of the Montreux Convention preventing 'aircraft carriers' transiting the Turkish Straits between the Soviet Black Sea bases and the Mediterranean Sea. These ships, while sized in the range of large fleet carriers, were designed to deploy alone or with escorts. In addition to supporting fighter aircraft and helicopters, they provide both strong defensive weaponry and heavy offensive missiles equivalent to a guided-missile cruiser.

By configuration

_during_sea_trial_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Aircraft carriers today are usually divided into the following four categories based on the way that aircraft take off and land:

- Catapult-assisted take-off barrier-arrested recovery (CATOBAR): these carriers generally carry the largest, heaviest, and most heavily armed aircraft, although smaller CATOBAR carriers may have other limitations (weight capacity of aircraft elevator, etc.). All CATOBAR carriers in service today are nuclear powered. Twelve are in service: ten Nimitz and one Gerald R. Ford-class fleet carriers in the United States; and one medium-sized carrier in France.

- Short take-off barrier-arrested recovery (STOBAR): these carriers are generally limited to carrying lighter fixed-wing aircraft with more limited payloads. STOBAR carrier air wings, such as the Sukhoi Su-33 and future Mikoyan MiG-29K wings of Admiral Kuznetsov are often geared primarily towards air superiority and fleet defense roles rather than strike/power projection tasks, which require heavier payloads (bombs and air-to-ground missiles). Five are in service: two in China; two in India and one in Russia.

- Short take-off vertical-landing (STOVL): limited to carrying STOVL aircraft. STOVL aircraft, such as the Harrier Jump Jet family and Yakovlev Yak-38 generally have limited payloads, lower performance, and high fuel consumption when compared with conventional fixed-wing aircraft; however, a new generation of STOVL aircraft, currently consisting of the Lockheed Martin F-35B Lightning II, has much improved performance. Fourteen are in service; nine STOVL amphibious assault ships in the US; two carriers each in Italy and the UK; and one STOVL amphibious assault ship in Spain.

- Helicopter carrier: Helicopter carriers have a similar appearance to other aircraft carriers but operate only helicopters – those that mainly operate helicopters but can also operate fixed-wing aircraft are known as STOVL carriers (see above). Seventeen are in service: four in Japan; three in France; two each in Australia, China, Egypt and South Korea; and one each in Brazil and Thailand. In the past, some conventional carriers were converted and these were called "commando carriers" by the Royal Navy. Some helicopter carriers, but not all, are classified as amphibious assault ships, tasked with landing and supporting ground forces on enemy territory.

By size

- Fleet carrier

- Light aircraft carrier

- Escort carrier

Supercarrier

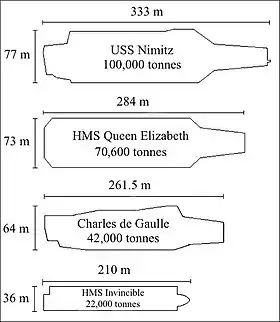

The appellation "supercarrier" is not an official designation with any national navy, but a term used predominantly by the media and typically when reporting on new and upcoming aircraft carrier types. It is also used when comparing carriers of various sizes and capabilities, both current and past. It was first used by The New York Times in 1938,[9] in an article about the Royal Navy's HMS Ark Royal, that had a length of 209 meters (686 ft), a displacement of 22,000 tonnes and was designed to carry 72 aircraft.[10][11] Since then, aircraft carriers have consistently grown in size, both in length and displacement, as well as improved capabilities; in defense, sensors, electronic warfare, propulsion, range, launch and recovery systems, number and types of aircraft carried and number of sorties flown per day.

China, Russia, and the United Kingdom all have carriers in service or under construction with displacements ranging from 65,000[12] to 85,000 tonnes[13] and lengths from 280 meters (920 ft)[14] to 320 meters (1,050 ft)[15] which have been described as "supercarriers".[16][17][13] The largest "supercarriers" in service as of 2022, however, are with the US Navy,[18] with displacements exceeding 100,000 tonnes,[18] lengths of over 337 meters (1,106 ft),[18] and capabilities that match or exceed that of any other class.[24]

Hull type identification symbols

Several systems of identification symbol for aircraft carriers and related types of ship have been used. These include the pennant numbers used by the Royal Navy, Commonwealth countries, and Europe, along with the hull classification symbols used by the US and Canada.[25]

| Symbol | Designation |

|---|---|

| CV | Generic aircraft carrier |

| CVA | Attack carrier (up to 1975) |

| CVB | Large aircraft carrier (retired 1952) |

| CVAN | Nuclear-powered attack carrier |

| CVE | Escort carrier |

| CVHA | Aircraft carrier, Helicopter Assault (retired) |

| CVHE | Aircraft carrier, Helicopter, Escort (retired) |

| CVV | Aircraft Carrier (Medium) (proposed) |

| CVL | Light aircraft carrier |

| CVN | Nuclear-powered aircraft carrier |

| CVS | Anti-submarine warfare carrier |

| CVT | Training Aircraft Carrier |

| LHA | Landing helicopter assault, a type of amphibious assault ship |

| LHD | Landing helicopter dock, a type of amphibious assault ship |

| LPH | Landing platform helicopter, a type of amphibious assault ship |

History

Origins

The 1903 advent of the heavier-than-air fixed-wing airplane with the Wright brothers' first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, was closely followed on 14 November 1910, by Eugene Burton Ely's first experimental take-off of a Curtiss Pusher airplane from the deck of a United States Navy ship, the cruiser USS Birmingham anchored off Norfolk Navy Base in Virginia. Two months later, on 18 January 1911, Ely landed his Curtiss Pusher airplane on a platform on the armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania anchored in San Francisco Bay. On 9 May 1912, the first take off of an airplane from a ship while underway was made by Commander Charles Samson flying a Short Improved S.27 biplane "S.38" of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) from the deck of the Royal Navy's pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Hibernia. Thus providing the first practical demonstration of the aircraft carrier for naval operations at sea.[26][27] Seaplane tender support ships came next, with the French Foudre of 1911.

Early in World War I, the Imperial Japanese Navy ship Wakamiya conducted the world's first successful ship-launched air raid:[28][29] on 6 September 1914, a Farman aircraft launched by Wakamiya attacked the Austro-Hungarian cruiser SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth and the Imperial German gunboat Jaguar in Kiaochow Bay off Tsingtao; neither was hit.[30][31] The first attack using an air-launched torpedo occurred on 2 August, when a torpedo was fired by Flight Commander Charles H. K. Edmonds from a Short Type 184 seaplane, launched from the seaplane carrier HMS Ben-my-Chree.[32][33]

The first carrier-launched airstrike was the Tondern raid in July 1918. Seven Sopwith Camels were launched from the battlecruiser HMS Furious which had been modified by replacing her forward turret with a flight deck and hangar turret. The Camels attacked and damaged the German airbase at Tondern, Germany (modern day Tønder, Denmark) and destroyed two zeppelin airships.[34]

The first landing of an airplane on a moving ship was by Squadron Commander Edwin Harris Dunning, when he landed his Sopwith Pup on HMS Furious in Scapa Flow, Orkney on 2 August 1917. Landing on the forward flight deck required the pilot to approach round the ship's superstructure, a difficult and dangerous manoeuver and Dunning was later killed when his airplane was thrown overboard while attempting another landing on Furious.[35] HMS Furious was modified again when her rear turret was removed and another flight deck added over a second hangar for landing aircraft over the stern.[36] Her funnel and superstructure remained intact however and turbulence from the funnel and superstructure was severe enough that only three landing attempts were successful before further attempts were forbidden.[37] This experience prompted the development of vessels with a flush deck and produced the first large fleet ships. In 1918, HMS Argus became the world's first carrier capable of launching and recovering naval aircraft.[38]

As a result of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, which limited the construction of new heavy surface combat ships, most early aircraft carriers were conversions of ships that were laid down (or had served) as different ship types: cargo ships, cruisers, battlecruisers, or battleships. These conversions gave rise to the US Lexington-class aircraft carriers (1927), Japanese Akagi and Kaga, and British Courageous class. Specialist carrier evolution was well underway, with several navies ordering and building warships that were purposefully designed to function as aircraft carriers by the mid-1920s. This resulted in the commissioning of ships such as the Japanese Hōshō (1922),[39] HMS Hermes (1924, although laid down in 1918 before Hōshō), and Béarn (1927). During World War II, these ships would become known as fleet carriers.

World War II

_in_Puget_Sound%252C_September_1945.jpg.webp)

The aircraft carrier dramatically changed naval warfare in World War II, because air power was becoming a significant factor in warfare. The advent of aircraft as focal weapons was driven by the superior range, flexibility, and effectiveness of carrier-launched aircraft. They had greater range and precision than naval guns, making them highly effective. The versatility of the carrier was demonstrated in November 1940, when HMS Illustrious launched a long-range strike on the Italian fleet at their base in Taranto, signalling the beginning of the effective and highly mobile aircraft strikes. This operation in the shallow water harbor incapacitated three of the six anchored battleships at a cost of two torpedo bombers.

World War II in the Pacific Ocean involved clashes between aircraft carrier fleets. The Japanese surprise attack on the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor naval and air bases on Sunday, 7 December 1941, was a clear illustration of the power projection capability afforded by a large force of modern carriers. Concentrating six carriers in a single unit turned naval history about, as no other nation had fielded anything comparable. Further versatility was demonstrated during the "Doolittle Raid", on 18 April 1942, when US Navy carrier USS Hornet sailed to within 650 nautical miles (1,200 km) of Japan and launched 16 B-25 bombers from her deck in a retaliatory strike on the mainland, including the capital, Tokyo. However, the vulnerability of carriers compared to traditional battleships when forced into a gun-range encounter was quickly illustrated by the sinking of HMS Glorious by German battleships during the Norwegian campaign in 1940.

This new-found importance of naval aviation forced nations to create a number of carriers, in efforts to provide air superiority cover for every major fleet in order to ward off enemy aircraft. This extensive usage led to the development and construction of 'light' carriers. Escort aircraft carriers, such as USS Bogue, were sometimes purpose-built but most were converted from merchant ships as a stop-gap measure to provide anti-submarine air support for convoys and amphibious invasions. Following this concept, light aircraft carriers built by the US, such as USS Independence, represented a larger, more "militarized" version of the escort carrier. Although with similar complement to escort carriers, they had the advantage of speed from their converted cruiser hulls. The UK 1942 Design Light Fleet Carrier was designed for building quickly by civilian shipyards and with an expected service life of about 3 years.[41] They served the Royal Navy during the war, and the hull design was chosen for nearly all aircraft carrier equipped navies after the war, until the 1980s. Emergencies also spurred the creation or conversion of highly unconventional aircraft carriers. CAM ships were cargo-carrying merchant ships that could launch (but not retrieve) a single fighter aircraft from a catapult to defend the convoy from long range land-based German aircraft.

Postwar era

_with_Hellcat_landing_c1953.jpg.webp)

_underway_in_the_Atlantic_Ocean_on_14_June_2004_(040614-N-0119G-020).jpg.webp)

Before World War II, international naval treaties of 1922, 1930, and 1936 limited the size of capital ships including carriers. Since World War II, aircraft carrier designs have increased in size to accommodate a steady increase in aircraft size. The large, modern Nimitz class of US Navy carriers has a displacement nearly four times that of the World War II–era USS Enterprise, yet its complement of aircraft is roughly the same—a consequence of the steadily increasing size and weight of individual military aircraft over the years. Today's aircraft carriers are so expensive that some nations which operate them risk significant economic and military impact if a carrier is lost.[42]

Some changes were made after 1945 in carriers:

- The angled flight deck was invented by Royal Navy Captain (later Rear Admiral) Dennis Cambell, as naval aviation jets higher speeds required carriers be modified to "fit" their needs.[43][44][45] Additionally, the angled flight deck allows for simultaneous launch and recovery.

- Jet blast deflectors became necessary to protect aircraft and handlers from jet blast. The first US Navy carriers to be fitted with them were the wooden-decked Essex-class aircraft carriers which were adapted to operate jets in the late 1940s. Later versions had to be water-cooled because of increasing engine power.[46]

- Optical landing systems were developed to facilitate the very precise landing angles required by jet aircraft, which have a fast landing speed giving little time to correct mistakes. The first system was fitted to HMS Illustrious in 1952.[46]

- Aircraft carrier designs have increased in size to accommodate continuous increase in aircraft size. The 1950s saw US Navy's commission of "supercarriers", designed to operate naval jets, which offered better performance at the expense of bigger size and demanded more ordnance to be carried on-board (fuel, spare parts, electronics, etc.).

- Increase in size and requirements of being capable of more than 30 knots and to be at sea for long periods meant nuclear reactors are now used by aboard larger aircraft carriers to generate the steam used to produce power for propulsion, electric power, catapulting airplanes in aircraft carriers, and a few more minor uses.[47]

Modern navies that operate such aircraft carriers treat them as the capital ship of the fleet, a role previously held by the sailing galleons, frigates and ships-of-the-line and later steam or diesel powered battleships. This change took place during World War II in response to air power becoming a significant factor in warfare, driven by the superior range, flexibility and effectiveness of carrier-launched aircraft. Following the war, carrier operations continued to increase in size and importance, and along with, carrier designs also increased in size and ability. Some of these larger carriers, dubbed by the media as "supercarriers", displacing 75,000 tonnes or greater, have become the pinnacle of carrier development. Some are powered by nuclear reactors and form the core of a fleet designed to operate far from home. Amphibious assault ships, such as the Wasp and Mistral classes, serve the purpose of carrying and landing Marines, and operate a large contingent of helicopters for that purpose. Also known as "commando carriers"[48] or "helicopter carriers", many have the capability to operate VSTOL aircraft.

The threatening role of aircraft carriers has a place in modern asymmetric warfare, like the gunboat diplomacy of the past.[49] Carriers also facilitate quick and precise projections of overwhelming military power into such local and regional conflicts.[50]

Lacking the firepower of other warships, carriers by themselves are considered vulnerable to attack by other ships, aircraft, submarines, or missiles. Therefore, an aircraft carrier is generally accompanied by a number of other ships to provide protection for the relatively unwieldy carrier, to carry supplies and perform other support services, and to provide additional offensive capabilities. The resulting group of ships is often termed a battle group, carrier group, carrier battle group or carrier strike group.

There is a view among some military pundits that modern anti-ship weapons systems, such as torpedoes and missiles, or even ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads have made aircraft carriers and carrier groups too vulnerable for modern combat.[51]

Carriers can also be vulnerable to diesel-electric submarines like the German U24 of the conventional 206 class which in 2001 "fired" at the Enterprise during the exercise JTFEX 01-2 in the Caribbean Sea by firing flares and taking a photograph through its periscope[52] or the Swedish Gotland which managed the same feat in 2006 during JTFEX 06-2 by penetrating the defensive measures of Carrier Strike Group 7 which was protecting USS Ronald Reagan.[53]

Description

Structure

Carriers are large and long ships, although there is a high degree of variation depending on their intended role and aircraft complement. The size of the carrier has varied over history and among navies, to cater to the various roles that global climates have demanded from naval aviation.

Regardless of size, the ship itself must house their complement of aircraft, with space for launching, storing, and maintaining them. Space is also required for the large crew, supplies (food, munitions, fuel, engineering parts), and propulsion. US aircraft carriers are notable for having nuclear reactors powering their systems and propulsion.

The top of the carrier is the flight deck, where aircraft are launched and recovered. On the starboard side of this is the island, where the funnel, air-traffic control and the bridge are located.

The constraints of constructing a flight deck affect the role of a given carrier strongly, as they influence the weight, type, and configuration of the aircraft that may be launched. For example, assisted launch mechanisms are used primarily for heavy aircraft, especially those loaded with air-to-ground weapons. CATOBAR is most commonly used on US Navy fleet carriers as it allows the deployment of heavy jets with full load-outs, especially on ground-attack missions. STOVL is used by other navies because it is cheaper to operate and still provides good deployment capability for fighter aircraft.

Due to the busy nature of the flight deck, only 20 or so aircraft may be on it at any one time. A hangar storage several decks below the flight deck is where most aircraft are kept, and aircraft are taken from the lower storage decks to the flight deck through the use of an elevator. The hangar is usually quite large and can take up several decks of vertical space.[54]

Munitions are commonly stored on the lower decks because they are highly explosive. Usually this is below the waterline so that the area can be flooded in case of emergency.

Flight deck

.jpg.webp)

As "runways at sea", aircraft carriers have a flat-top flight deck, which launches and recovers aircraft. Aircraft launch forward, into the wind, and are recovered from astern. The flight deck is where the most notable differences between a carrier and a land runway are found. Creating such a surface at sea poses constraints on the carrier. For example, the fact that it is a ship means that a full-length runway would be costly to construct and maintain. This affects take-off procedure, as a shorter runway length of the deck requires that aircraft accelerate more quickly to gain lift. This either requires a thrust boost, a vertical component to its velocity, or a reduced take-off load (to lower mass). The differing types of deck configuration, as above, influence the structure of the flight deck. The form of launch assistance a carrier provides is strongly related to the types of aircraft embarked and the design of the carrier itself.

There are two main philosophies in order to keep the deck short: add thrust to the aircraft, such as using a Catapult Assisted Take-Off (CATO-); and changing the direction of the airplanes' thrust, as in Vertical and/or Short Take-Off (V/STO-). Each method has advantages and disadvantages of its own:

- Catapult assisted take-off but arrested recovery (CATOBAR): A steam- or electric-powered catapult is connected to the aircraft, and is used to accelerate conventional aircraft to a safe flying speed. By the end of the catapult stroke, the aircraft is airborne and further propulsion is provided by its own engines. This is the most expensive method as it requires complex machinery to be installed under the flight deck, but allows for even heavily loaded aircraft to take off.

- Short take-off but arrested recovery (STOBAR) depends on increasing the net lift on the aircraft. Aircraft do not require catapult assistance for take off; instead on nearly all ships of this type an upwards vector is provided by a ski-jump at the forward end of the flight deck, often combined with thrust vectoring by the aircraft. Alternatively, by reducing the fuel and weapon load, an aircraft is able to reach faster speeds and generate more upwards lift and launch without a ski-jump or catapult.

- Short take-off vertical-landing (STOVL): On aircraft carriers, non-catapult-assisted, fixed-wing short takeoffs are accomplished with the use of thrust vectoring, which may also be used in conjunction with a runway "ski-jump". Use of STOVL tends to allow aircraft to carry a larger payload as compared to during VTOL use, while still only requiring a short runway. The most famous examples are the Hawker Siddeley Harrier and the BAe Sea Harrier. Although technically VTOL aircraft, they are operationally STOVL aircraft due to the extra weight carried at take-off for fuel and armaments. The same is true of the Lockheed F-35B Lightning II, which demonstrated VTOL capability in test flights but is operationally STOVL or in the case of UK uses "shipborne rolling vertical landing"

- Vertical take-off and landing (VTOL): Aircraft are specifically designed for the purpose of using very high degrees of thrust vectoring (e.g. if the thrust to weight-force ratio is greater than 1, it can take off vertically), but are usually slower than conventionally propelled aircraft.

On the recovery side of the flight deck, the adaptation to the aircraft load-out is mirrored. Non-VTOL or conventional aircraft cannot decelerate on their own, and almost all carriers using them must have arrested-recovery systems (-BAR, e.g. CATOBAR or STOBAR) to recover their aircraft. Aircraft that are landing extend a tailhook that catches on arrestor wires stretched across the deck to bring themselves to a stop in a short distance. Post-World War II Royal Navy research on safer CATOBAR recovery eventually led to universal adoption of a landing area angled off axis to allow aircraft who missed the arresting wires to "bolt" and safely return to flight for another landing attempt rather than crashing into aircraft on the forward deck.

If the aircraft are VTOL-capable or helicopters, they do not need to decelerate and hence there is no such need. The arrested-recovery system has used an angled deck since the 1950s because, in case the aircraft does not catch the arresting wire, the short deck allows easier take off by reducing the number of objects between the aircraft and the end of the runway. It also has the advantage of separating the recovery operation area from the launch area. Helicopters and aircraft capable of vertical or short take-off and landing (V/STOL) usually recover by coming abreast of the carrier on the port side and then using their hover capability to move over the flight deck and land vertically without the need for arresting gear.

Staff and deck operations

Carriers steam at speed, up to 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph) into the wind during flight deck operations to increase wind speed over the deck to a safe minimum. This increase in effective wind speed provides a higher launch airspeed for aircraft at the end of the catapult stroke or ski-jump, as well as making recovery safer by reducing the difference between the relative speeds of the aircraft and ship.

Since the early 1950s on conventional carriers it has been the practice to recover aircraft at an angle to port of the axial line of the ship. The primary function of this angled deck is to allow aircraft that miss the arresting wires, referred to as a bolter, to become airborne again without the risk of hitting aircraft parked forward. The angled deck allows the installation of one or two "waist" catapults in addition to the two bow cats. An angled deck also improves launch and recovery cycle flexibility with the option of simultaneous launching and recovery of aircraft.

Conventional ("tailhook") aircraft rely upon a landing signal officer (LSO, radio call sign 'paddles') to monitor the aircraft's approach, visually gauge glideslope, attitude, and airspeed, and transmit that data to the pilot. Before the angled deck emerged in the 1950s, LSOs used colored paddles to signal corrections to the pilot (hence the nickname). From the late 1950s onward, visual landing aids such as the optical landing system have provided information on proper glide slope, but LSOs still transmit voice calls to approaching pilots by radio.

Key personnel involved in the flight deck include the shooters, the handler, and the air boss. Shooters are naval aviators or naval flight officers and are responsible for launching aircraft. The handler works just inside the island from the flight deck and is responsible for the movement of aircraft before launching and after recovery. The "air boss" (usually a commander) occupies the top bridge (Primary Flight Control, also called primary or the tower) and has the overall responsibility for controlling launch, recovery and "those aircraft in the air near the ship, and the movement of planes on the flight deck, which itself resembles a well-choreographed ballet."[55] The captain of the ship spends most of his time one level below primary on the Navigation Bridge. Below this is the Flag Bridge, designated for the embarked admiral and his staff.

To facilitate working on the flight deck of a US aircraft carrier, the sailors wear colored shirts that designate their responsibilities. There are at least seven different colors worn by flight deck personnel for modern United States Navy carrier air operations. Carrier operations of other nations use similar color schemes.

Deck structures

_211_lands_aboard_the_aircraft_carrier_USS_Enterprise_(CVN_65).jpg.webp)

The superstructure of a carrier (such as the bridge, flight control tower) are concentrated in a relatively small area called an island, a feature pioneered on HMS Hermes in 1923. While the island is usually built on the starboard side of the flight deck, the Japanese aircraft carriers Akagi and Hiryū had their islands built on the port side. Very few carriers have been designed or built without an island. The flush deck configuration proved to have significant drawbacks, primary of which was management of the exhaust from the power plant. Fumes coming across the deck were a major issue in USS Langley. In addition, lack of an island meant difficulties managing the flight deck, performing air traffic control, a lack of radar housing placements and problems with navigating and controlling the ship itself.[56]

Another deck structure that can be seen is a ski-jump ramp at the forward end of the flight deck. This was first developed to help launch short take off vertical landing (STOVL) aircraft take off at far higher weights than is possible with a vertical or rolling takeoff on flat decks. Originally developed by the Royal Navy, it since has been adopted by many navies for smaller carriers. A ski-jump ramp works by converting some of the forward rolling movement of the aircraft into vertical velocity and is sometimes combined with the aiming of jet thrust partly downwards. This allows heavily loaded and fueled aircraft a few more precious seconds to attain sufficient air velocity and lift to sustain normal flight. Without a ski-jump, launching fully-loaded and fueled aircraft such as the Harrier would not be possible on a smaller flat deck ship before either stalling out or crashing directly into the sea.

Although STOVL aircraft are capable of taking off vertically from a spot on the deck, using the ramp and a running start is far more fuel efficient and permits a heavier launch weight. As catapults are unnecessary, carriers with this arrangement reduce weight, complexity, and space needed for complex steam or electromagnetic launching equipment. Vertical landing aircraft also remove the need for arresting cables and related hardware. Russian, Chinese, and Indian carriers include a ski-jump ramp for launching lightly loaded conventional fighter aircraft but recover using traditional carrier arresting cables and a tailhook on their aircraft.

The disadvantage of the ski-jump is the penalty it exacts on aircraft size, payload, and fuel load (and thus range); heavily laden aircraft can not launch using a ski-jump because their high loaded weight requires either a longer takeoff roll than is possible on a carrier deck, or assistance from a catapult or JATO rocket. For example, the Russian Sukhoi Su-33 is only able to launch from the carrier Admiral Kuznetsov with a minimal armament and fuel load. Another disadvantage is on mixed flight deck operations where helicopters are also present, such as on a US landing helicopter dock or landing helicopter assault amphibious assault ship. A ski jump is not included as this would eliminate one or more helicopter landing areas; this flat deck limits the loading of Harriers but is somewhat mitigated by the longer rolling start provided by a long flight deck compared to many STOVL carriers.

National fleets

The US Navy has the largest fleet of carriers in the world, with eleven supercarriers currently in service. The UK has two STOVL carriers in service. China and India have two STOBAR carriers in service. The navies of France and Russia each operate a single medium-size carrier. The US also has nine similarly sized Amphibious Warfare Ships. There are three small light carriers in use capable of operating both fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters; Italy operates two, and Spain one.

Additionally there are seventeen small carriers which only operate helicopters serving the navies of Australia (2), Brazil (1), China (2), Egypt (2), France (3), Japan (4), South Korea (2), and Thailand (1).

Australia

- Current

_at_berth_prior_to_commissioning.jpg.webp)

The Royal Australian Navy operates two Canberra-class landing helicopter docks. The two-ship class, based on the Spanish vessel Juan Carlos I and built by Navantia and BAE Systems Australia, represents the largest ships ever built for the Royal Australian Navy.

HMAS Canberra underwent sea trials in late 2013 and was commissioned in 2014. Her sister ship, HMAS Adelaide, was commissioned in December 2015. The Australian ships retain the ski-ramp from the Juan Carlos I design, although the RAN has not acquired carrier-based fixed-wing aircraft.

Brazil

- Current

In December 2017, the Brazilian Navy confirmed the purchase of HMS Ocean for (GBP) £84.6 million (equivalent to R$359.5M and US$113.2M) and renamed it Atlântico. The ship was decommissioned from Royal Navy service in March 2018. The Brazilian Navy commissioned the carrier on 29 June 2018 in the United Kingdom. After undertaking a period of maintenance in the UK, was expected to travel to its home port, Arsenal do Rio de Janeiro (AMRJ) and be fully operational by 2020.[58][59][60] The ship displaces 21,578 tonnes, is 203.43 meters (667.4 ft) long and has a range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi).[61][62]

Before leaving HMNB Devonport for its new homeport in Rio's Navy Arsenal, Atlântico underwent operational sea training under the Royal Navy's Flag Officer Sea Training (FOST) program.[63][64]

On 12 November 2020, Atlântico was redesignated "NAM", for "multipurpose aircraft carrier" (Portuguese: Navio Aeródromo Multipropósito), from "PHM", for "multipurpose helicopter carrier" (Portuguese: Porta-Helicópteros Multipropósito), to reflect its capability to operate with fixed-wing medium-altitude long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicles as well as crewed tiltrotor VTOL aircraft.

China

- Current

2 STOBAR carriers:

- Liaoning (60,900 tons) was originally built as the Soviet Kuznetsov-class carrier Varyag[66] and was later purchased as a hulk in 1998 on the pretext of use as a floating casino, then towed to China for rebuild and completion.[67][68] Liaoning was commissioned on 25 September 2012 and began service for testing and training.[69] In November 2012, Liaoning launched and recovered Shenyang J-15 naval fighter aircraft for the first time.[70][71] After a refit in January 2019, she was assigned to the North Sea Fleet, a change from its previous role as a training carrier.[72]

- Shandong (60,000-70,000 tons) was launched on 26 April 2017. She is the first to be built domestically, to an improved Kuznetsov-class design. Shandong started sea trials on 23 April 2018,[73] and entered service in December 2019.[74]

1 CATOBAR carrier:

- Fujian (80,000 tons) is China's only CATOBAR carrier that underwent construction between 2015 and 2016 before being completed in June 2022.[75] She is being fitted out as of 2022 and will commence in-service in 2023–2024.[76][77][78]

2 Landing helicopter docks

- A Type 075 LHD, Hainan was commissioned on 23 April 2021 at the naval base in Sanya.[79] A second ship, Guangxi, was commissioned on 26 December 2021.[80]

- Future

China has had a long-term plan to operate six large aircraft carriers with two carriers per fleet.[81]

China is planning a class of eight landing helicopter dock vessels, the Type 075 (NATO reporting name Yushen-class landing helicopter assault). This is a class of amphibious assault ship under construction by the Hudong–Zhonghua Shipbuilding company.[82] The first ship was commissioned in April 2021.[79] China is also planning a modified class of the same concept, the Type 076 landing helicopter dock, that will also be equipped with an electromagnetic catapult launch system.[83]

Egypt

- Current

Egypt signed a contract with French shipbuilder DCNS to buy two Mistral-class helicopter carriers for approximately 950 million euros. The two ships were originally destined for Russia, but the deal was cancelled by France due to Russian involvement in Ukraine.[84]

On 2 June 2016, Egypt received the first of two helicopter carriers acquired in October 2015, the landing helicopter dock Gamal Abdel Nasser. The flag transfer ceremony took place in the presence of Egyptian and French Navies' chiefs of staff, chairman and chief executive officers of both DCNS and STX France, and senior Egyptian and French officials.[85] On 16 September 2016, DCNS delivered the second of two helicopter carriers, the landing helicopter dock Anwar El Sadat which also participated in a joint military exercise with the French Navy before arriving at its home port of Alexandria.[86]

Egypt is so far the only country in Africa or the Middle East to possess a helicopter carrier.[87]

France

_underway_in_the_Red_Sea_on_15_April_2019_(190415-N-IL409-0017).JPG.webp)

- Current

The French Navy operates the Charles de Gaulle, a 42,000-tonne nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, commissioned in 2001 and is the flagship of the French Navy. The ship carries a complement of Dassault Rafale M and E‑2C Hawkeye aircraft, EC725 Caracal and AS532 Cougar helicopters for combat search and rescue, as well as modern electronics and Aster missiles. She is a CATOBAR-type carrier that uses two 75 m C13‑3 steam catapults of a shorter version of the catapult system installed on the US Nimitz-class carriers, one catapult at the bow and one across the front of the landing area.[88] In addition, the French Navy operates three Mistral-class amphibious assault ships.[89]

- Future

In October 2018, the French Ministry of Defence began an 18-month study for €40 million for the eventual future replacement of the French aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle beyond 2030. In December 2020, President Macron announced that construction of the next generation carrier would begin in around 2025 with sea trials to start in about 2036. The carrier is planned to have a displacement of around 75,000 tons and to carry about 32 next-generation fighters, two to three E-2D Advanced Hawkeyes and a yet-to-be-determined number of unmanned carrier air vehicles.[90]

India

.png.webp)

- Current

2 STOBAR carrier:

INS Vikramaditya, 45,400 tonnes, modified Kiev class. The carrier was purchased by India on 20 January 2004 after years of negotiations at a final price of $2.35 billion. The ship successfully completed her sea trials in July 2013 and aviation trials in September 2013. She was formally commissioned on 16 November 2013 at a ceremony held at Severodvinsk, Russia.[91]

INS Vikrant, also known as Indigenous Aircraft Carrier 1 (IAC-1) a 45,000-tonne, 262-metre-long (860 ft)[92] aircraft carrier whose keel was laid in 2009.[93] The new carrier will operate MiG-29K and naval HAL Tejas aircraft.[93] The ship is powered by four gas-turbine engines and has a range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 kilometres), carrying 160 officers, 1,400 sailors, 10 helicopters and 30 aircraft.[94] The ship was launched in 2013, sea-trials began in August 2021 and was commissioned on 02 September 2022.[95] [96]

- Future

India has plans for a third carrier, INS Vishal, also known as Indigenous Aircraft Carrier 2 (IAC-2) with a displacement of over 65,000 tonnes is planned with a CATOBAR system to launch and recover heavier aircraft.[97]

Italy

- Current

2 STOVL carriers:

- Giuseppe Garibaldi: 14,000-tonne Italian STOVL carrier, commissioned in 1985.

- Cavour: 30000-tonne Italian STOVL carrier designed and built with secondary amphibious assault facilities, commissioned in 2008.[98]

- Future

Italy plans to replace ageing aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi, as well as one of the San Giorgio-class landing helicopter docks, with a new amphibious assault ship, to be named Trieste.[99][100] The ship will be significantly larger than her predecessors with a displacement of 38,000 tonnes at full load. Trieste is to carry the F-35B Joint Strike Fighter.[101][102] Meanwhile, Giuseppe Garibaldi will be transferred to Italian Space Operation Command for use as a satellite launch platform.[103]

Japan

.jpg.webp)

- Current

4 helicopter carriers:

- 2 Hyūga-class helicopter destroyers – 19,000-tonne (full load) anti-submarine warfare carriers with enhanced command-and-control capabilities allowing them to serve as fleet flagships.

- 2 Izumo-class helicopter destroyers – 820-foot-long (250 m), 19,500-tonne (27,000 tonnes full load) helicopter carrier Izumo was launched August 2013 and commissioned March 2015. This is the largest military ship Japan has had since World War II.[104] Izumo's sister ship, Kaga, was commissioned in 2017.

- Future

2 STOVL carriers: In December 2018, the Japanese Cabinet gave approval to convert both Izumo-class destroyers into aircraft carriers for F-35B STOVL operations.[105] The conversion of Izumo was underway as of mid-2020.[106] The modification of maritime escort vessels is to "increase operational flexibility" and enhance Pacific air defense,[108] the Japanese defense ministry's position is "We are not creating carrier air wings or carrier air squadrons" similar to the US Navy. The Japanese STOVL F-35s, when delivered, will be operated by the Japan Air Self Defense Force from land bases; according to the 2020 Japanese Defense Ministry white paper the STOVL model was chosen for the JASDF due the lack of appropriately long runways to support air superiority capability across all of Japanese airspace.[109][110] Japan has requested that the USMC deploy STOVL F-35s and crews aboard the Izumo-class ships "for cooperation and advice on how to operate the fighter on the deck of the modified ships".[111]

Russia

- Current

1 STOBAR carrier: Admiral Flota Sovetskogo Soyuza Kuznetsov: 55,000-tonne Admiral Kuznetsov-class STOBAR aircraft carrier. Launched in 1985 as Tbilisi, renamed and operational from 1995. Without catapults she can launch and recover lightly fueled naval fighters for air defense or anti-ship missions but not heavy conventional bombing strikes. Officially designated an aircraft carrying cruiser, she is unique in carrying a heavy cruiser's complement of defensive weapons and large P-700 Granit offensive missiles. The P-700 systems will be removed in the coming refit to enlarge her below decks aviation facilities as well as upgrading her defensive systems.[112][113]

- Future

The Russian Government has been considering the potential replacement of Admiral Kuznetsov for some time and has considered the Shtorm-class aircraft carrier as a possible option. This carrier will be a hybrid of CATOBAR and STOBAR, given the fact that she utilizes both systems of launching aircraft. The carrier is expected to cost between $1.8 billion and $5.63 billion.[114] As of 2020, the project had not yet been approved and, given the financial costs, it was unclear whether it would be made a priority over other elements of Russian naval modernization.[115]

A class of 2 LHD, Project 23900 is planned and an official keel laying ceremony for the project happened on 20 July 2020.[116]

South Korea

- Current

Two Dokdo-class 18,860-tonne full deck amphibious assault ships with hospital and well deck and facilities to serve as fleet flagships.

- Future

South Korea has set tentative plans for procuring two light aircraft carriers by 2033, which would help make the ROKN a blue water navy.[117][118] In December 2020, details of South Korea's planned carrier program (CVX) were finalized. A vessel of about 40,000 tons is envisaged carrying about 20 F-35B fighters as well as future maritime attack helicopters. Service entry had been anticipated in the early 2030s.[119] The program has encountered opposition in the National Assembly. In November 2021, the National Defense Committee of the National Assembly reduced the program's requested budget of 7.2 billion KRW and to just 500 million KRW (about $400K USD), effectively putting the project on hold, at least temporarily.[120] However, on 3 December 2021 the full budget of 7.2 billion won was passed by the National Assembly.[117] Basic design work is to begin in earnest starting 2022.[121]

Spain

.jpg.webp)

- Current

Juan Carlos I: 27,000-tonne, specially designed multipurpose strategic projection ship which can operate as an amphibious assault ship and aircraft carrier. Juan Carlos I has full facilities for both functions including a ski jump for STOVL operations, is equipped with the AV-8B Harrier II attack aircraft. Also, well deck, and vehicle storage area which can be used as additional hangar space, launched in 2008, commissioned 30 September 2010.[122]

Thailand

- Current

1 offshore helicopter support ship: HTMS Chakri Naruebet helicopter carrier: 11,400-tonne STOVL carrier based on Spanish Príncipe de Asturias design. Commissioned in 1997. The AV-8S Matador/Harrier STOVL fighter wing, mostly inoperable by 1999,[123] was retired from service without replacement in 2006.[124] As of 2010, the ship is used for helicopter operations and for disaster relief.[125]

Turkey

- Future

TCG Anadolu is a 24,660-tonne planned amphibious assault ship (LHD) of the Turkish Navy that can be configured as a 27,079-tonne light aircraft carrier.[126] Construction began on 30 April 2016 by Sedef Shipbuilding Inc. at their Istanbul shipyard and is expected to be completed by the end of 2020.[127] The construction of a sister ship, to be named TCG Trakya, is currently being planned by the Turkish Navy.[128][129]

United Kingdom

.jpg.webp)

- Current

Two 65,000-tonne[12] Queen Elizabeth-class STOVL carriers which operates the F-35 Lightning II. HMS Queen Elizabeth was commissioned in December 2017[130] and HMS Prince of Wales in December 2019.

Queen Elizabeth undertook her first operational deployment in 2021.[131] Each Queen Elizabeth-class ship is able to operate around 40 aircraft during peacetime operations and is thought to be able to carry up to 72 at maximum capacity.[132] As of the end of April 2020, 18 F-35B aircraft had been delivered to the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. "Full operating capability" for the UK's carrier strike capability had been planned for 2023 (2 squadrons or 24 jets operating from one carrier).[133] The longer-term aim remains for the ability to conduct a wide range of air operations and support amphibious operations worldwide from both carriers by 2026.[133] They form the central part of the UK Carrier Strike Group.

- Future

The Queen Elizabeth-class ships are expected to have service lives of 50 years,[134] therefore there are not imminent studies on their replacement.

United States

.jpg.webp)

- Current

11 CATOBAR carriers, all nuclear-powered:

- Nimitz class: ten 101,000-tonne, 333-meter-long (1,092 ft) fleet carriers, the first of which was commissioned in 1975. A Nimitz-class carrier is powered by two nuclear reactors providing steam to four steam turbines.

- Gerald R. Ford class, one 100,000-tonne, 337-meter-long (1,106 ft) fleet carrier. The lead of the class Gerald R. Ford came into service in 2017, with another nine planned.

Nine amphibious assault ships carrying vehicles, Marine fighters, attack and transport helicopters, and landing craft with STOVL fighters for CAS and CAP:

- America class: a class of 45,000-tonne amphibious assault ships, although the lead ship in this class does not have a well deck. Two ships in service out of a planned 11 ships. Ships of this class can have a secondary mission as a light carrier with 20 AV-8B Harrier II, and in the future the F-35B Lightning II aircraft after unloading their Marine expeditionary unit.

- Wasp class: a class of eight 41,000-tonne amphibious assault ships, members of this class have been used in wartime in their secondary mission as light carriers with 20 to 25 AV-8Bs after unloading their Marine expeditionary unit.

_artist_depiction.jpg.webp)

- Future

The current US fleet of Nimitz-class carriers will be followed into service (and in some cases replaced) by the Gerald R. Ford class. It is expected that the ships will be more automated in an effort to reduce the amount of funding required to maintain and operate the vessels. The main new features are implementation of Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) (which replace the old steam catapults) and unmanned aerial vehicles.[135] In terms of carrier future developments, Congress has discussed possibly accelerating the phasing out of one or more Nimitz-class carriers, postponing or canceling the procurement of the CVN-82 and CVN-81, or modifying the purchase contract.[136]

Following the deactivation of USS Enterprise in December 2012, the US fleet comprised 10 fleet carriers, but that number increased back to 11 with the commissioning of Gerald R. Ford in July 2017. The House Armed Services Seapower subcommittee on 24 July 2007, recommended seven or eight new carriers (one every four years). However, the debate has deepened over budgeting for the $12–14.5 billion (plus $12 billion for development and research) for the 100,000-tonne Gerald R. Ford-class carrier (estimated service 2017) compared to the smaller $2 billion 45,000-tonne America-class amphibious assault ships, which are able to deploy squadrons of F-35Bs. The first of this class, USS America, is now in active service with another, USS Tripoli, and 9 more are planned.[137][138]

In a report to Congress in February 2018, the Navy stated it intends to maintain a "12 CVN force" as part of its 30-year acquisition plan.[139]

Aircraft carriers in preservation

Current museum carriers

A few aircraft carriers have been preserved as museum ships. They are:

- USS Yorktown (CV-10) in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina

- USS Intrepid (CV-11) in New York City

- USS Hornet (CV-12) in Alameda, California

- USS Lexington (CV-16) in Corpus Christi, Texas

- USS Midway (CV-41) in San Diego, California

- Soviet aircraft carrier Kiev in Tianjin, China

- Soviet aircraft carrier Minsk in Nantong, China

Former museum carriers

- INS Vikrant (R11) was moored as a museum in Mumbai from 2001 to 2012, but was never able to find an industrial partner and was closed that year. She was scrapped in 2014.[140]

- USS Cabot (CVL-28) was acquired for preservation and moored in New Orleans from 1990 to 2002, but due to an embezzlement scandal, funding for the museum never materialized and the ship was scrapped in 2002.

Future museum carriers

- USS Tarawa (LHA-1) has a preservation campaign to bring her to the West Coast of the United States as the world's first amphibious assault ship museum.[141]

See also

- Airborne aircraft carrier

- Aviation-capable naval vessels

- Carrier-based aircraft

- Lily and Clover

- Merchant aircraft carrier

- Mobile offshore base

- Project Habakkuk

- Seadrome

- Submarine aircraft carrier

- Unsinkable aircraft carrier

Related lists

- List of aircraft carriers

- List of aircraft carriers in service

- List of aircraft carriers by configuration

- List of aircraft carriers of the Second World War

- List of sunken aircraft carriers

- List of amphibious warfare ships

- List of carrier-based aircraft

- List of Canadian Navy aircraft carriers

- List of aircraft carriers of the People's Liberation Army Navy (China)

- List of current French Navy aircraft carriers

- List of German aircraft carriers

- List of aircraft carriers of the Indian Navy

- List of Italian Navy aircraft carriers

- List of aircraft carriers of the Japanese Navy

- List of aircraft carriers of Russia and the Soviet Union

- List of active Spanish aircraft carriers

- List of aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy

- List of escort carriers of the Royal Navy

- List of seaplane carriers of the Royal Navy

- List of aircraft carriers of the United States Navy

- List of aircraft carrier classes of the United States Navy

- List of escort aircraft carriers of the United States Navy

References

- "Aircraft carrier", Dictionary, Reference, archived from the original on 19 February 2014, retrieved 3 October 2013

- "World Wide Aircraft Carriers", Military, Global Security, archived from the original on 6 December 2011, retrieved 8 December 2011

- "Aircraft Carrier", Encyclopaedia, Britannica, archived from the original on 5 October 2013, retrieved 3 October 2013,

Subsequent design modifications produced such variations as the light carrier, equipped with large amounts of electronic gear for the detection of submarines, and the helicopter carrier, intended for conducting amphibious assault. ... Carriers with combined capabilities are classified as multipurpose carriers.

- Petty, Dan. "Fact File: Amphibious Assault Ships – LHA/LHD/LHA(R)". U.S. Navy. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Aircraft carriers crucial, Royal Navy chief warns". BBC News. 4 July 2012. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "The slow death of the carrier air wing". jalopnik.com. 19 July 2017. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Drew, James (8 July 2015). "US "carrier gap" could see naval air power dip in Gulf region". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Will the Aircraft Carrier Survive?". 13 December 2018. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Reich's Cruise Ships Held Potential Plane Carriers". The New York Times. 1 May 1938. p. 32. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2015.(subscription required)

- "The Ark Royal Launched. Most Up-To-Date Carrier. Aircraft in the Fleet". The Times. 14 April 1937. p. 11.

- Rossiter, Mike (2007) [2006]. Ark Royal: the life, death and rediscovery of the legendary Second World War aircraft carrier (2nd ed.). London: Corgi Books. pp. 48–51. ISBN 978-0-552-15369-0. OCLC 81453068.

- "HMS Queen Elizabeth". royalnavy.mod.uk. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "China kicks off construction of new supercarrier/". thediplomat.com. 5 January 2018. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "Queen Elizabeth Class". Royal Navy. Archived from the original on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- "China has solid plans for four aircraft carriers by 2030, could eventually have 10". nextbigfuture.com. 19 February 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "British super carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth to deploy to the Pacific". ukdefencejournal.org.uk. 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "Russian Navy may get advanced new aircraft carrier". tass.com. 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78)". militaryfactory.com/. 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "The world's most advanced aircraft carrier is one step closer to completion". businessinsider.com. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "Sneak peak at US Navy's $13B aircraft carrier". cnn.com. 18 July 2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "USS Gerald R. Ford: Inside the world's most advanced aircraft carrier". foxnews.com. 21 July 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "USS Gerald R. Ford ushers in new age of technology and innovation". navylive.dodlive.mil. 21 July 2017. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "The US Navy's new $13 billion aircraft carrier will dominate the seas". marketwatch.com. 9 March 2016. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- [19][20][21][22][23]

- "AWD, Hobart, MFU or DDGH – What's in a Name?". Semaphore. Royal Australian Navy. 30 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- "The Naval Review and the Aviators". Flight. Vol. IV, no. 177. 18 May 1912. p. 442. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Flight From the Hibernia". The Times. No. 39895. London. 10 May 1912. p. 8 (3).

- "IJN Wakamiya Aircraft Carrier". globalsecurity.org. 2015. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Polak 2005, p. 92.

- Donko, Wilhelm M. (2013). Österreichs Kriegsmarine in Fernost: Alle Fahrten von Schiffen der k.(u.)k. Kriegsmarine nach Ostasien, Australien und Ozeanien von 1820 bis 1914. Berlin Epubli. pp. 4, 156–162, 427.

- "IJN Wakamiya Aircraft Carrier". globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Sturtivant 1990, p. 215.

- 269 Squadron History: 1914–1923

- Probert, p. 46

- The First World War: A Complete History by Sir Martin Gilbert Archived 5 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Parkes, p. 622.

- Parkes, p. 624.

- Till 1996, p. 191.

- "Japanese inventions that changed the world". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Enright & Ryan, p. xiv

- Robbins, Guy (2001). The Aircraft Carrier Story: 1908–1945. London: Cassel. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-30435-308-8.

- Cochran, Daniel (2018). "Will the Aircraft Carrier Survive?; Future Air Threats to the Carrier (and How to Defend It)". Joint Air Power Competence Centre (japcc.org). Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "The Angled Deck Story". denniscambell.org.uk. 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- "History of Fleet Air Arm Officers Association". FAAOA.org. 2015. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Hone, Thomas C.; Friedman, Norman; Mandeles, Mark D. (2011). "Innovation in Carrier Aviation". Newport Paper 37. Naval War College Press.; abridged findings published as "The Development of the Angled-Deck Aircraft Carrier". Naval War College Review. 64 (2): 63–78. Spring 2011.

- Hobbs 2009, Chapter 14

- "Nuclear-Powered Ships | Nuclear Submarines". world-nuclear.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- A number of British conversions of light fleet carriers to helicopter operations were known as commando carriers, though they did not operate landing craft

- Pike, John. "Gunboat Diplomacy: Does It Have A Place in the 1990s?". Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- Lekic, Slobodan (8 May 2011). "Navies expanding use of aircraft carriers". Navy Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Hendrix, Henry J.; Williams, J. Noel (May 2011). "Twilight of the $UPERfluous Carrier". Proceedings. Vol. 137. U.S. Naval Institute. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Deutsches U-Boot fordert US-Marine heraus" (in German). t-online. 6 January 2013. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- "Pentagon: New Class Of Silent Submarines Poses Threat". KNBC. 19 October 2006. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2006.

- Harris, Tom (29 August 2002). "How Aircraft Carriers Work". How Stuff Works. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013.

- "The US Navy Aircraft Carriers". Navy.mil. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- Friedman 1983, pp. 241–243.

- Barreira, Victor (7 December 2017). "Brazil hopes to buy, commission UK's HMS Ocean by June 2018". Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017.

- "O Ocean é do Brasil! MB conclui a compra do porta-helicópteros por 84 milhões de libras e dá à Força um novo capitânia – Poder Naval – A informação naval comentada e discutida". 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Defensa.com (22 December 2017). "La Marina de Brasil compra el portaviones HMS Ocean a la Royal Navy británica-noticia defensa.com". Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "PHM Atlântico: características técnicas e operacionais". naval.com.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). 24 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "PHM A-140 Atlântico é armado com canhão Bushmaster MK.44 II de 30 mm". tecnodefesa.com.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). 8 July 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Barreira, Victor (29 June 2018). "Brazil commissions helicopter carrier". janes.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018.

- "Mostra de Armamento do Porta-Helicópteros Multipropósito Atlântico". naval.com.br. 29 June 2018. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- "China aircraft carrier confirmed by general". BBC News. 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- "China brings its first aircraft carrier into service, joining 9-nation club". Behind The Wall. NBC. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Liaoning, ex-Varyag". Global Security. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "China's first aircraft carrier enters service". BBC News. 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Axe, David (26 November 2012). "China's aircraft carrier successfully launches its first jet fighters". Wired. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "China lands first jet on its aircraft carrier". Fox News. 25 November 2012. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Military Watch Magazine". militarywatchmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- "China's first home-grown Type 001A aircraft carrier begins maiden sea trial". South China Morning Post. 23 April 2018. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Myers, Steven Lee (17 December 2019). "China Commissions 2nd Aircraft Carrier, Challenging US Dominance". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022.

- Jack Lau (17 June 2022). "China launches Fujian, PLA Navy's 3rd aircraft carrier". South China Morning Post.

- Chan, Minnie (14 February 2017). "No advanced jet launch system for China's third aircraft carrier, experts say". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017.

- "Satellite images show how work on China's new Type 002 aircraft carrier is coming along". South China Morning Post. 7 May 2019. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "Images show construction of China's third aircraft carrier, thinktank says". The Guardian. 7 May 2019. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Vavasseur, Xavier (24 April 2021). "China Commissions a Type 055 DDG, a Type 075 LHD and a Type 094 SSBN in a Single Day". Naval News. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- Vavasseur, Xavier (30 December 2021). "China's 2nd Type 075 LHD Guangxi 广西 Commissioned With PLAN". Naval News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- "China's Plan for 6 Aircraft Carriers Just 'Sank'". 9 December 2019. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Sea trials for Chinese Navy Type 075 LHD Landing Helicopter Dock amphibious assault ship". navyrecognition.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- "China planning advanced amphibious assault ship". 27 July 2020. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- "Egypt signs Mistral contract with France". defenceweb.co.za. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "DCNS DELIVERS THE FIRST MISTRAL-CLASS HELICOPTER CARRIER TO THE EGYPTIAN NAVY, THE LHD GAMAL ABDEL NASSER". 2 June 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- "DCNS DELIVERS THE SECOND MISTRAL-CLASS HELICOPTER CARRIER TO THE EGYPTIAN NAVY, THE LHD ANWAR EL SADAT". 16 September 2016. Archived from the original on 22 September 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- "Egypt is only Middle East country to own Mistral helicopter carriers". 8 October 2016. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Pike, John. "Charles de Gaulle". globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "Mistral Class – Amphibious Assault Ships – Naval Technology". Naval Technology. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- "President Macron Announces Start of New French Nuclear Aircraft Carrier Program". 8 December 2020. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- "Aircraft carrier INS Vikramaditya inducted into Indian Navy". IBN Live. IN. Archived from the original on 18 November 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "'Historical moment': Sea trials begin for India's first indigenous aircraft carrier INS Vikrant [VIDEO]". timesnownews.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- "Indian Aircraft Carrier (Project 71)". Indian Navy [Bharatiya Nau Sena]. Bharat Rakshak. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- Reporter, B. S. (11 June 2015). "Cochin Shipyard undocks INS Vikrant". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2018 – via Business Standard.

- "Indigenous Aircraft Carrier, to be named INS Vikrant, is biggest ship made in India". The Hindu. Special Correspondent. 25 June 2021. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "India's indigenous aircraft carrier and largest warship INS Vikrant joins Navy". The Hindu. Dinaker Peri. 2 September 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "US-India Collaboration on Aircraft Carriers: A Good Idea?". Archived from the original on 19 May 2015.

- "Cavour Page". World Wide Aircraft Carriers. Free webs. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Piano di dismissioni delle Unità Navali entro il 2025" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2017.

- "Documento Programmatico Pluriennale 2017–2019" (PDF) (in Italian). Minestro della Difesa. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "Third Italian F-35B Goes to the Italian Air Force. And the Italian Navy Is Not Happy at All". The Aviationist. 26 February 2020. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ""Fulge super mare", risplende sul mare la nuova nave da assalto anfibio multiruolo costruita a Castellammare di Stabia" (Press release) (in Italian). Marina Militare. 17 August 2021. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- (di Tiziano Ciocchetti). "Il Garibaldi lancerà in orbita satelliti - Difesa Online" (in Italian). Difesaonline.it. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Luthra, Gulshan (August 2013). "Indian Navy to launch indigenous aircraft carrier August 12". Indiastrategic.in. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Japan to have first aircraft carriers since World War II". CNN. 18 December 2018. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "Japanese Izumo carrier modification progresses well". 29 June 2020. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Brad Lendon and Yoko Wakatsuki (18 December 2018). "Japan to have first aircraft carriers since World War II". CNN. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- "Lack of runways spurred Japan's F-35B purchase". airforce-technology.com. 21 August 2020. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Expanding as Tokyo Takes New Approach to Maritime Security". 29 May 2019. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Marines Considering Flying U.S. F-35Bs off of Japan's Largest Warships". 23 August 2019. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- "Moscow set to upgrade Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier". RIA Navosti. 6 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Admiral Flota Sovetskogo Soyuza Kuznetsov". Rus navy. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Russia developing $5 bln aircraft carrier with no world analogs—fleet commander". TASS. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "Military Watch Magazine". militarywatchmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Vavasseur, Xavier (21 July 2020). "Russia Lays Keels of Next Gen LHD, Submarines and Frigates in Presence of Russian President Putin". Naval News. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- "국방 분야 핵심공약 좌초 우려에 정무라인 물밑작업 끝 원안 통과문대통령, 경항모 중요성 거듭 강조…예산부활 보고받고는 '반색". yna.co.kr. 3 December 2021. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- "S. Korea Envisions Light Aircraft Carrier". Defense News. 15 January 2014. Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- "South Korea Officially Starts LPX-II Aircraft Carrier Program". 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Lee, Daehan (16 November 2021). "South Korea's CVX Aircraft Carrier Project Faces New Budget Cuts". Naval News. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- "결국 되살아난 '경항모 예산' 72억…해군, 내년 기본설계 추진". hankyung.com. 3 December 2021. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- Head, Jeff, "BPE", World wide aircraft carriers, Free webs, archived from the original on 9 April 2013, retrieved 8 April 2013

- Carpenter & Wiencek, Asian Security Handbook 2000, p. 302.

- Cooper., Peter (8 March 2011). "End of a Legend – Harrier Farewell". Pacificwingsmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012s. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Thai Aircraft Carrier Assists Southern Relief Efforts | Pattaya Daily News – Pattaya Newspaper, Powerful news at your fingertips". Pattaya Daily News. 4 November 2010. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- "Uçak Gemisi Olan Ülkeleri Öğrenelim". Enkucuk.com. 23 November 2017. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Turkish Navy's flagship to enter service in 2020, Anadolu Agency, archived from the original on 30 November 2019, retrieved 21 November 2019

- Anıl Şahin (14 February 2019). "Deniz Kuvvetlerinden TCG Trakya açıklaması". SavunmaSanayiST.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Ahmet Doğan (9 November 2019). "TCG Trakya ne zaman bitecek?". DenizHaber.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Coughlin, Con (26 June 2017), "HMS Queen Elizabeth will help Britain retake its place among the military elite", The Telegraph, archived from the original on 10 August 2018, retrieved 10 August 2018

- "HMS Queen Elizabeth Closer to Becoming Operational as Carrier Leaves for Trials". Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- "HMS Queen Elizabeth: All You Need to Know About Britain's Aircraft Carrier". Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- "Carrier Strike – Preparing for deployment" (PDF). National Audit Office. 26 June 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Queen Elizabeth Class Aircraft Carriers". Babcock International (babcockinternational.com). Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Aircraft Carriers – CVN". US Navy. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- O'Rourke, R. (2015). Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service Washington.

- Kreisher, Otto (October 2007). "Seven New Carriers (Maybe)". Air Force Magazine. Vol. 90, no. 10. Air Force Association. pp. 68–71. ISSN 0730-6784. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- "Huntington Ingalls, Newport News shipyard upbeat despite budget clouds". Daily Press. 8 May 2014. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- "Navy Submits 30-Year Ship Acquisition Plan". Navy. 12 February 2018. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "INS Vikrant, hero of '71 war, reduced to heap of scrap". The Indian Express. 22 November 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2022.