Rastafari

Rastafari, sometimes called Rastafarianism, is a religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is classified as both a new religious movement and a social movement by scholars of religion. There is no central authority in control of the movement and much diversity exists among practitioners, who are known as Rastafari, Rastafarians, or Rastas.

.svg.png.webp)

Rastafari beliefs are based on a specific interpretation of the Bible. Central is a monotheistic belief in a single God, referred to as Jah, who is deemed to partially reside within each individual. Rastas accord key importance to Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia between 1930 and 1974; many regard him as the Second Coming of Jesus and Jah incarnate, while others see him as a human prophet who fully recognised Jah's presence in every individual. Rastafari is Afrocentric and focuses attention on the African diaspora, which it believes is oppressed within Western society, or "Babylon". Many Rastas call for this diaspora's resettlement in Africa, a continent they consider the Promised Land, or "Zion". Some practitioners extend these views into black supremacism. Rastas refer to their practices as "livity". Communal meetings are known as "groundations", and are typified by music, chanting, discussions, and the smoking of cannabis, the latter regarded as a sacrament with beneficial properties. Rastas emphasise what they regard as living "naturally", adhering to ital dietary requirements, wearing their hair in dreadlocks, and following patriarchal gender roles.

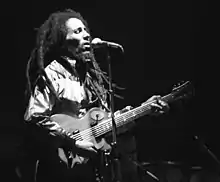

Rastafari originated among impoverished and socially disenfranchised Afro-Jamaican communities in 1930s Jamaica. Its Afrocentric ideology was largely a reaction against Jamaica's then-dominant British colonial culture. It was influenced by both Ethiopianism and the Back-to-Africa movement promoted by black nationalist figures such as Marcus Garvey. The religion developed after several Protestant Christian clergymen, most notably Leonard Howell, proclaimed that Haile Selassie's crowning as Emperor of Ethiopia in 1930 fulfilled a Biblical prophecy. By the 1950s, Rastafari's countercultural stance had brought the movement into conflict with wider Jamaican society, including violent clashes with law enforcement. In the 1960s and 1970s, it gained increased respectability within Jamaica and greater visibility abroad through the popularity of Rastafari-inspired reggae musicians, most notably Bob Marley. Enthusiasm for Rastafari declined in the 1980s, following the deaths of Haile Selassie and Marley, but the movement survived and has a presence in many parts of the world.

The Rastafari movement is decentralised and organised on a largely sectarian basis. There are several denominations, or "Mansions of Rastafari", the most prominent of which are the Nyahbinghi, Bobo Ashanti, and the Twelve Tribes of Israel, each offering a different interpretation of Rastafari belief. There are an estimated 700,000 to 1,000,000 Rastafari across the world. The largest population is in Jamaica, although small communities can be found in most of the world's major population centres. Most Rastafari are of black African descent, and some groups accept only black members.

Definition

Rastafari has been described as a religion,[1] meeting many of the proposed definitions for what constitutes a religion,[2] and is legally recognised as such in various countries.[3] Multiple scholars of religion have categorised Rastafari as a new religious movement,[4] while some scholars have also classified it as a sect,[5] a cult,[6] and a revitalisation movement.[7] Having arisen in Jamaica, it has been described as an Afro-Jamaican religion,[8] and more broadly an Afro-Caribbean religion.[9]

Although Rastafari focuses on Africa as a source of identity, it is a product of creolisation processes in the Americas,[10] described by the Hispanic studies scholars Margarite Fernández Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert as "a Creole religion, rooted in African, European, and Indian practices and beliefs".[11] The scholar Ennis B. Edmonds also suggested that Rastafari was "emerging" as a world religion, not because of the number of its adherents, but because of its global spread.[12] Many Rastas nevertheless reject descriptions of Rastafari as a religion, instead referring to it as a "way of life",[13] a "philosophy",[14] or a "spirituality".[15]

Emphasising its political stance, particularly in support of African nationalism and pan-Africanism, some academics have characterised Rastafari as a political movement,[16] a "politico-religious" movement,[17] or a protest movement.[18] It has alternatively been labelled a social movement,[19] or more specifically as a new social movement,[7] and a cultural movement.[20] Many Rastas or Rastafarians—as practitioners are known—nevertheless dislike the labelling of Rastafari as a "movement".[21] In 1989, a British Industrial Tribunal concluded that—for the purposes of the Race Relations Act 1976—Rastafarians could be considered an ethnic group because they have a long, shared heritage which distinguished them from other groups, their own cultural traditions, a common language, and a common religion.[22]

Rastafari has continuously changed and developed,[23] with significant doctrinal variation existing among practitioners depending on the group to which they belong.[24] It is not a unified movement,[25] and there has never been a single leader followed by all Rastafari.[26] It is thus difficult to make broad generalisations about the movement without obscuring the complexities within it.[27] The scholar of religion Darren J. N. Middleton suggested that it was appropriate to speak of "a plethora of Rasta spiritualities" rather than a single phenomenon.[28]

The term "Rastafari" derives from "Ras Tafari Makonnen", the pre-regnal title of the late Haile Selassie, the former Ethiopian emperor who occupies a central role in Rasta belief. The term "Ras" means a duke or prince in the Ethiopian Semitic languages; "Tafari Makonnen" was Selassie's personal name.[29] It is unknown why the early Rastas adopted this form of Haile Selassie's name as the basis of the term for their religion.[30] As well as being the religion's name, "Rastafari" is also used for the religion's practitioners themselves.[31] Many commentators—including some academic sources[32] and some practitioners[33]—refer to the movement as "Rastafarianism".[34] However, the term is disparaged by many Rastafari, who believe that the use of -ism implies religious doctrine and institutional organisation, things they wish to avoid.[35]

Beliefs

Rastas refer to the totality of their religion's ideas and beliefs as "Rastalogy".[36] Edmonds described Rastafari as having "a fairly cohesive worldview";[36] however, the scholar Ernest Cashmore thought that its beliefs were "fluid and open to interpretation".[37] Within the movement, attempts to summarise Rastafari belief have never been accorded the status of a catechism or creed.[38] Rastas place great emphasis on the idea that personal experience and intuitive understanding should be used to determine the truth or validity of a particular belief or practice.[39] No Rasta, therefore, has the authority to declare which beliefs and practices are orthodox and which are heterodox.[38] The conviction that Rastafari has no dogma "is so strong that it has itself become something of a dogma", according to the sociologist of religion Peter B. Clarke.[40]

Rastafari is deeply influenced by Judeo-Christian religion,[41] and shares many commonalities with Christianity.[42] The scholar Michael Barnett observed that its theology is "essentially Judeo-Christian", representing "an Afrocentralized blend of Christianity and Judaism".[43] Some followers openly describe themselves as Christians.[44] Rastafari accords the Bible a central place in its belief system, regarding it as a holy book,[45] and adopts a literalist interpretation of its contents.[46] According to the anthropologist Stephen D. Glazier, Rasta approaches to the Bible result in the religion adopting an outlook very similar to that of some forms of Protestantism.[47] Rastas regard the Bible as an authentic account of early black African history and of their place as God's favoured people.[40] They believe the Bible to be key to understanding both the past and the present and for predicting the future,[40] while also regarding it as a source book from which they can form and justify their beliefs and practices.[48] Rastas commonly perceive the final book of the Bible, the Book of Revelation, as the most important part, because they see its contents as having particular significance for the world's present situation.[49]

Contrary to scholarly understandings of how the Bible was compiled, Rastas commonly believe it was originally written on stone in the Ethiopian language of Amharic.[50] They also believe that the Bible's true meaning has been warped, both through mistranslation into other languages and by deliberate manipulation by those seeking to deny black Africans their history.[51] They also regard it as cryptographic, meaning that it has many hidden meanings.[52] They believe that its true teachings can be revealed through intuition and meditation on the "book within" which allows them to commune with God.[40] Because of what they regard as the corruption of the Bible, Rastas also turn to other sources that they believe shed light on black African history.[53] Common texts used for this purpose include Leonard Howell's 1935 work The Promised Key, Robert Athlyi Rogers' 1924 book Holy Piby, and Fitz Balintine Pettersburg's 1920s work, the Royal Parchment Scroll of Black Supremacy.[53] Many Rastas also treat the Kebra Nagast, a 14th-century Ethiopian text, as a source through which to interpret the Bible.[54]

Jah and Jesus of Nazareth

Rastas are monotheists, worshipping a singular God whom they call Jah. The term "Jah" is a shortened version of "Jehovah", the name of God in English translations of the Old Testament.[55] Rastafari holds strongly to the immanence of this divinity;[56] as well as regarding Jah as a deity, Rastas believe that Jah is inherent within each individual.[57] This belief is reflected in the aphorism, often cited by Rastas, that "God is man and man is God",[58] and Rastas speak of "knowing" Jah, rather than simply "believing" in him.[59] In seeking to narrow the distance between humanity and divinity, Rastafari embraces mysticism.[7]

Jesus is an important figure in Rastafari.[60] However, practitioners reject the traditional Christian view of Jesus, particularly the depiction of him as a white European, believing that this is a perversion of the truth.[61] They believe that Jesus was a black African, and that the white Jesus was a false god.[62] Many Rastas regard Christianity as the creation of the white man;[63] they treat it with suspicion out of the view that the oppressors (white Europeans) and the oppressed (black Africans) cannot share the same God.[64] Many Rastas take the view that the God worshipped by most white Christians is actually the Devil,[65] and a recurring claim among Rastas is that the Pope is Satan or the Antichrist.[66] Rastas therefore often view Christian preachers as deceivers[65] and regard Christianity as being guilty of furthering the oppression of the African diaspora,[67] frequently referring to it as having perpetrated "mental enslavement".[68]

Haile Selassie

From its origins, Rastafari was intrinsically linked with Haile Selassie, the Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974.[69] He remains the central figure in Rastafari ideology,[70] and although all Rastas hold him in esteem, precise interpretations of his identity differ.[71] Understandings of how Haile Selassie relates to Jesus vary among Rastas.[72] Many, although not all, believe that the Ethiopian monarch was the Second Coming of Jesus,[73] legitimising this by reference to their interpretation of the nineteenth chapter of the Book of Revelation.[60] By viewing Haile Selassie as Jesus, these Rastas also regard him as the messiah prophesied in the Old Testament,[74] the manifestation of God in human form,[71] and "the living God".[75] Some perceive him as part of a Trinity, alongside God as Creator and the Holy Spirit, the latter referred to as "the Breath within the temple".[76] Rastas who view Haile Selassie as Jesus argue that both were descendants from the royal line of the Biblical king David,[60] while Rastas also emphasise the fact that the Makonnen dynasty, of which Haile Selassie was a member, claimed descent from the Biblical figures Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.[77]

Other Rastas see Selassie as embodying Jesus' teachings and essence but reject the idea that he was the literal reincarnation of Jesus.[78] Members of the Twelve Tribes of Israel denomination, for instance, reject the idea that Selassie was the Second Coming, arguing that this event has yet to occur.[58] From this perspective, Selassie is perceived as a messenger or emissary of God rather than a manifestation of God himself.[79] Rastas holding to this view sometimes regard the deification of Haile Selassie as naïve or ignorant,[80] in some cases thinking it as dangerous to worship a human being as God.[81] There are various Rastas who went from believing that Haile Selassie was both God incarnate and the Second Coming of Jesus to seeing him as something distinct.[82]

On being crowned, Haile Selassie was given the title of "King of Kings and Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah".[83] Rastas use this title for Haile Selassie alongside others, such as "Almighty God", "Judge and Avenger", "King Alpha and Queen Omega", "Returned Messiah", "Elect of God", and "Elect of Himself".[84] Rastas also view Haile Selassie as a symbol of their positive affirmation of Africa as a source of spiritual and cultural heritage.[85]

While he was emperor, many Jamaican Rastas professed the belief that Haile Selassie would never die.[86] The 1974 overthrow of Haile Selassie by the military Derg and his subsequent death in 1975 resulted in a crisis of faith for many practitioners.[87] Some left the movement altogether.[88] Others remained, and developed new strategies for dealing with the news. Some Rastas believed that Selassie did not really die and that claims to the contrary were Western misinformation.[89] To bolster their argument, they pointed to the fact that no corpse had been produced; in reality, Haile Selassie's body had been buried beneath his palace, remaining undiscovered there until 1992.[90] Another perspective within Rastafari acknowledged that Haile Selassie's body had perished, but claimed that his inner essence survived as a spiritual force.[91] A third response within the Rastafari community was that Selassie's death was inconsequential as he had only been a "personification" of Jah rather than Jah himself.[92]

During his life, Selassie described himself as a devout Christian.[93] In a 1967 interview, Selassie was asked about the Rasta belief that he was the Second Coming of Jesus, to which he responded: "I have heard of this idea. I also met certain Rastafarians. I told them clearly that I am a man, that I am mortal, and that I will be replaced by the oncoming generation, and that they should never make a mistake in assuming or pretending that a human being is emanated from a deity."[94] His grandson Ermias Sahle Selassie has said that there is "no doubt that Haile Selassie did not encourage the Rastafari movement".[95] Critics of Rastafari have used this as evidence that Rasta theological beliefs are incorrect,[96] although some Rastas take Selassie's denials as evidence that he was indeed the incarnation of God, based on their reading of the Gospel of Luke.[lower-alpha 1][97]

Afrocentrism and views on race

.svg.png.webp)

According to Clarke, Rastafari is "concerned above all else with black consciousness, with rediscovering the identity, personal and racial, of black people".[98] The Rastafari movement began among Afro-Jamaicans who wanted to reject the British colonial culture that dominated Jamaica and replace it with a new identity based on a reclamation of their African heritage.[85] Its emphasis is on the purging of any belief in the inferiority of black people, and the superiority of white people, from the minds of its followers.[99] Rastafari is therefore Afrocentric,[100] equating blackness with the African continent,[64] and endorsing a form of Pan-Africanism.[101]

Practitioners of Rastafari identify themselves with the ancient Israelites—God's chosen people in the Old Testament—and believe that black Africans broadly or Rastas more specifically are either the descendants or the reincarnations of this ancient people.[102] This is similar to beliefs in Judaism,[103] although many Rastas believe that contemporary Jews' status as the descendants of the ancient Israelites is a false claim.[104] Rastas typically believe that black Africans are God's chosen people, meaning that they made a covenant with him and thus have a special responsibility.[105] Rastafari espouses the view that this, the true identity of black Africans, has been lost and needs to be reclaimed.[106]

There is no uniform Rasta view on race.[103] Black supremacy was a theme early in the movement, with the belief in the existence of a distinctly black African race that is superior to other racial groups. While some still hold this belief, non-black Rastas are now widely accepted in the movement.[107] Rastafari's history has opened the religion to accusations of racism.[108] Cashmore noted that there was an "implicit potential" for racism in Rasta beliefs but he also noted that racism was not "intrinsic" to the religion.[109] Some Rastas have acknowledged that there is racism in the movement, primarily against Europeans and Asians.[103] Some Rasta sects reject the notion that a white European can ever be a legitimate Rasta.[103] Other Rasta sects believe that an "African" identity is not inherently linked to black skin but rather is about whether an individual displays an African "attitude" or "spirit".[110]

Babylon and Zion

Rastafari teaches that the black African diaspora are exiles living in "Babylon", a term which it applies to Western society.[111] For Rastas, European colonialism and global capitalism are regarded as manifestations of Babylon,[112] while police and soldiers are viewed as its agents.[113] The term "Babylon" is adopted because of its Biblical associations. In the Old Testament, Babylon is the Mesopotamian city where the Israelites were held captive, exiled from their homeland, between 597 and 586 BCE;[114] Rastas compare the exile of the Israelites in Mesopotamia to the exile of the African diaspora outside Africa.[115] In the New Testament, "Babylon" is used as a euphemism for the Roman Empire, which was regarded as acting in a destructive manner that was akin to the way in which the ancient Babylonians acted.[114] Rastas perceive the exile of the black African diaspora in Babylon as an experience of great suffering,[116] with the term "suffering" having a significant place in Rasta discourse.[117]

_-_ETH_-_UNOCHA.svg.png.webp)

Rastas view Babylon as being responsible for both the Atlantic slave trade which removed enslaved Africans from their continent and the ongoing poverty which plagues the African diaspora.[118] Rastas turn to Biblical scripture to explain the Atlantic slave trade,[119] believing that the enslavement, exile, and exploitation of black Africans was punishment for failing to live up to their status as Jah's chosen people.[120] Many Rastas, adopting a Pan-Africanist ethos, have criticised the division of Africa into nation-states, regarding this as a Babylonian development,[121] and are often hostile to capitalist resource extraction from the continent.[122] Rastas seek to delegitimise and destroy Babylon, something often conveyed in the Rasta aphorism "Chant down Babylon".[118] Rastas often expect the white-dominated society to dismiss their beliefs as false, and when this happens they see it as confirmation of the correctness of their faith.[123]

Rastas view "Zion" as an ideal to which they aspire.[118] As with "Babylon", this term comes from the Bible, where it refers to an idealised Jerusalem.[118] Rastas use "Zion" either for Ethiopia specifically or for Africa more broadly, the latter having an almost mythological identity in Rasta discourse.[124] Many Rastas use the term "Ethiopia" as a synonym for "Africa";[125] thus, Rastas in Ghana for instance described themselves as already living within "Ethiopia".[126] Other Rastas apply the term "Zion" to Jamaica or they use it to describe a state of mind.[115]

In portraying Africa as their "Promised Land", Rastas reflect their desire to escape what they perceive as the domination and degradation that they experience in Babylon.[127] During the first three decades of the Rastafari movement, it placed strong emphasis on the need for the African diaspora to be repatriated to Africa.[127] To this end, various Rastas lobbied the Jamaican government and United Nations to oversee this resettlement process.[127] Other Rastas organised their own transportation to the African continent.[127] Critics of the movement have argued that the migration of the entire African diaspora to Africa is implausible, particularly as no African country would welcome this.[96]

By the movement's fourth decade, the desire for physical repatriation to Africa had declined among Rastas,[128] a change influenced by observation of the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia.[129] Rather, many Rastas saw the idea of returning to Africa in a metaphorical sense, entailing the restoration of their pride and self-confidence as people of black African descent.[130] The term "liberation before repatriation" began to be used within the movement.[131] Some Rastas seek to transform Western society so that they may more comfortably live within it rather than seeking to move to Africa.[132] There are nevertheless many Rastas who continue to emphasise the need for physical resettlement of the African diaspora in Africa.[128]

Salvation and paradise

Rastafari is a millenarian movement,[133] espousing the idea that the present age will come to an apocalyptic end.[134] Many practitioners believe that on this Day of Judgement, Babylon will be overthrown,[135] with Rastas being the chosen few who survive the upheaval.[136] With Babylon destroyed, Rastas believe that humanity will be ushered into a "new age".[137] This is conceived as being a millennium of peace, justice, and happiness in which the righteous shall live in Africa, now a paradise.[138] In the 1980s, many Rastas believed that the Day of Judgment would happen around the year 2000.[139] A view then common in the Rasta community was that the world's white people would wipe themselves out through nuclear war,[140] with black Africans then ruling the world, something that they argued was prophesied in the Book of Daniel.[lower-alpha 2][140]

Rastas do not believe that there is a specific afterlife to which individuals go following bodily death.[141] They believe in the possibility of eternal life,[65] and that only those who shun righteousness will actually die.[142] The scholar of religion Leonard E. Barrett observed some Jamaican Rastas who believed that those practitioners who did die had not been faithful to Jah.[143] He suggested that this attitude stemmed from the large numbers of young people that were then members of the movement, and who had thus seen only few Rastas die.[144] Another Rasta view is that those who are righteous will undergo reincarnation,[145] with an individual's identity remaining throughout each of their incarnations.[146] In keeping with their views on death, Rastas eschew celebrating physical death and often avoid funerals,[147] also repudiating the practice of ancestor veneration that is common among traditional African religions.[148]

Morality, ethics, and gender roles

Most Rastas share a pair of fundamental moral principles known as the "two great commandments": love of God and love of neighbour.[149] Many Rastas believe that to determine whether they should undertake a certain act or not, they should consult the presence of Jah within themselves.[150]

Rastafari promotes the idea of "living naturally",[151] in accordance with what Rastas regard as nature's laws.[152] It endorses the idea that Africa is the "natural" abode of black Africans, a continent where they can live according to African culture and tradition and be themselves on a physical, emotional, and intellectual level.[110] Practitioners believe that Westerners and Babylon have detached themselves from nature through technological development and thus have become debilitated, slothful, and decadent.[153] Some Rastas express the view that they should adhere to what they regard as African laws rather than the laws of Babylon, thus defending their involvement in certain acts which may be illegal in the countries that they are living in,[154] for example defending the smoking of cannabis as a religious sacrament.[155] In emphasising this Afrocentric approach, Rastafari expresses overtones of black nationalism.[156]

The scholar Maureen Warner-Lewis observed that Rastafari combined a "radical, even revolutionary" stance on socio-political issues, particularly regarding race, with a "profoundly traditional" approach to "philosophical conservatism" on other religious issues.[157] Rastas typically look critically upon modern capitalism with its consumerism and materialism.[150] They favour small-scale, pre-industrial and agricultural societies.[158] Some Rastas have promoted activism as a means of achieving socio-political reform, while others believe in awaiting change that will be brought about through divine intervention in human affairs.[159] In Jamaica, Rastas typically do not vote,[160] derogatorily dismissing politics as "politricks",[161] and rarely involve themselves in political parties or unions.[162] The Rasta tendency to believe that socio-political change is inevitable opens the religion up to the criticism from the political left that it encourages adherents to do little or nothing to alter the status quo.[163] Other Rastas do engage in political activism; the Ghanaian Rasta singer-songwriter Rocky Dawuni for instance was involved in campaigns promoting democratic elections,[164] while in Grenada, many Rastas joined the People's Revolutionary Government formed in 1979.[165]

Gender roles and sexuality

Rastafari promotes what it regards as the restoration of black manhood, believing that men in the African diaspora have been emasculated by Babylon.[166] It espouses patriarchal principles,[167] including the idea that women should submit to male leadership.[168] External observers—including scholars such as Cashmore and Edmonds[169]—have claimed that Rastafari accords women an inferior position to men.[132] Rastafari women usually accept this subordinate position and regard it as their duty to obey their men;[170] the academic Maureen Rowe suggested that women were willing to join the religion despite its restrictions because they valued the life of structure and discipline it provided.[171] Rasta discourse often presents women as morally weak and susceptible to deception by evil,[172] and claims that they are impure while menstruating.[173] Rastas legitimise these gender roles by citing Biblical passages, particularly those in the Book of Leviticus and in the writings of Paul the Apostle.[174]

Rasta women usually wear clothing that covers their head and hides their body contours.[175] Trousers are usually avoided,[176] in favour of long skirts.[177] Women are expected to cover their head while praying,[178] and in some Rasta groups this is expected of them whenever in public.[179] Rasta discourse insists this female dress code is necessary to prevent women from attracting men and presents it as an antidote to the sexual objectification of women in Babylon.[180] Rasta men are permitted to wear whatever they choose.[181] Although men and women took part alongside each other in early Rasta rituals, from the late 1940s and 1950s the Rasta community increasingly encouraged gender segregation for ceremonies.[182] This was legitimised with the explanation that women were impure through menstruation and that their presence at the ceremonies would distract male participants.[182]

As it existed in Jamaica, Rastafari did not promote monogamy.[183] Rasta men are permitted multiple female sex partners,[184] while women are expected to reserve their sexual activity for one male partner.[185] Marriage is not usually formalised through legal ceremonies but is a common-law affair,[186] although many Rastas are legally married.[187] Rasta men refer to their female partners as "queens",[188] or "empresses",[189] while the males in these relationships are known as "kingmen".[190] Rastafari places great importance on family life and the raising of children,[191] with reproduction being encouraged.[192] The religion emphasises the place of men in child-rearing, associating this with the recovery of African manhood.[193] Women often work, sometimes while the man raises the children at home.[194] Rastafari typically rejects feminism,[195] although since the 1970s growing numbers of Rasta women have called for greater gender equity in the movement.[196] The scholar Terisa E. Turner for instance encountered Kenyan feminists who were appropriating Rastafari content to suit their political agenda.[197] Some Rasta women have challenged gender norms by wearing their hair uncovered in public and donning trousers.[189]

Rastafari regards procreation as the purpose of sex, and thus oral and anal sex are usually forbidden.[198] Both contraception and abortion are usually censured,[199] and a common claim in Rasta discourse is that these were inventions of Babylon to decrease the black African birth-rate.[200] Rastas typically express hostile attitudes to homosexuality, regarding homosexuals as evil and unnatural;[201] this attitude derives from references to same-sex sexual activity in the Bible.[46] Homosexual Rastas probably conceal their sexual orientation because of these attitudes.[202] Rastas typically see the growing acceptance of birth control and homosexuality in Western society as evidence of the degeneration of Babylon as it approaches its apocalyptic end.[203]

Practices

Rastas refer to their cultural and religious practices as "livity".[204] Rastafari does not place emphasis on hierarchical structures.[150] It has no professional priesthood,[36] with Rastas believing that there is no need for a priest to act as mediator between the worshipper and divinity.[205] It nevertheless has "elders", an honorific title bestowed upon those with a good reputation among the community.[206] Although respected figures, they do not necessarily have administrative functions or responsibilities.[206] When they do oversee ritual meetings, they are often responsible for helping to interpret current events in terms of Biblical scripture.[207] Elders often communicate with each other through a network to plan movement events and form strategies.[206]

Grounding

The term "grounding" is used among Rastas to refer to the establishment of relationships between like-minded practitioners.[208] Groundings often take place in a commune or yard, and are presided over by an elder.[194] The elder is charged with keeping discipline and can ban individuals from attending.[206] The number of participants can range from a handful to several hundred.[194] Activities that take place at groundings include the playing of drums, chanting, the singing of hymns, and the recitation of poetry.[209] Cannabis, known as ganja, is often smoked.[209] Most groundings contain only men, although some Rasta women have established their own all-female grounding circles.[210]

One of the central activities at groundings is "reasoning".[211] This is a discussion among assembled Rastas about the religion's principles and their relevance to current events.[212] These discussions are supposed to be non-combative, although attendees can point out the fallacies in any arguments presented.[213] Those assembled inform each other about the revelations that they have received through meditation and dream.[194] Each contributor is supposed to push the boundaries of understanding until the entire group has gained greater insight into the topic under discussion.[214] In meeting together with like-minded individuals, reasoning helps Rastas to reassure one another of the correctness of their beliefs.[96] Rastafari meetings are opened and closed with prayers. These involve supplication of God, the supplication for the hungry, sick, and infants, and calls for the destruction of the Rastas' enemies, and then close with statements of adoration.[215]

Princes shall come out of Egypt, Ethiopia shall stretch forth her hand unto God. Oh thou God of Ethiopia, thou God of divine majesty, thy spirit come within our hearts to dwell in the parts of righteousness. That the hungry be fed, the sick nourished, the aged protected, and the infant cared for. Teach us love and loyalty as it is in Zion.

— Opening passage of a common Rasta prayer[215]

The largest groundings were known as "groundations" or "grounations" in the 1950s, although they were subsequently re-termed "Nyabinghi Issemblies".[216] The term "Nyabinghi" is adopted from the name of a mythical African queen.[217] Nyabinghi Issemblies are often held on dates associated with Ethiopia and Haile Selassie.[218] These include Ethiopian Christmas (7 January), the day on which Haile Selassie visited Jamaica (21 April), Selassie's birthday (23 July), Ethiopian New Year (11 September), and Selassie's coronation day (2 November).[218] Some Rastas also organise Nyabinghi Issemblies to mark Jamaica's Emancipation Day (1 August) and Marcus Garvey's birthday (17 August).[218]

Nyabinghi Issemblies typically take place in rural areas, being situated in the open air or in temporary structures—known as "temples" or "tabernacles"—specifically constructed for the purpose.[219] Any elder seeking to sponsor a Nyabinghi Issembly must have approval from other elders and requires the adequate resources to organise such an event.[220] The assembly usually lasts between three and seven days.[219] During the daytime, attendees engage in food preparation, ganja smoking, and reasoning, while at night they focus on drumming and dancing around bonfires.[219] Nyabinghi Issemblies often attract Rastas from a wide area, including from different countries.[219] They establish and maintain a sense of solidarity among the Rasta community and cultivate a feeling of collective belonging.[219] Unlike in many other religions, rites of passage play no role in Rastafari;[221] on death, various Rastas have been given Christian funerals by their relatives, as there are no established Rasta funeral rites.[222]

Use of cannabis

The principal ritual of Rastafari is the smoking of ganja, also known as marijuana or cannabis.[223] Among the names that Rastas give to the plant are callie, Iley, "the herb", "the holy herb", "the grass", and "the weed".[224] Cannabis is usually smoked during groundings,[194] although some practitioners also smoke it informally in other contexts.[225] Some Rastas smoke it almost all of the time, something other practitioners regard as excessive,[226] and many practitioners also ingest cannabis in a tea, as a spice in cooking, and as an ingredient in medicine.[227] However, not all Rastas use ganja;[228] abstainers explain that they have already achieved a higher level of consciousness and thus do not require it.[229]

In Rastafari, cannabis is considered a sacrament.[230] Rastas argue that the use of ganja is promoted in the Bible, specifically in Genesis,[lower-alpha 3] Psalms,[lower-alpha 4] and Revelation.[lower-alpha 5][231] They regard it as having healing properties,[232] eulogise it for inducing feelings of "peace and love",[233] and claim that it cultivates a form of personal introspection that allows the smokers to discover their inner divinity.[234] Some Rastas believe that cannabis smoke serves as an incense that counteracts immoral practices in society.[202]

Rastas typically smoke cannabis in the form of a large, hand-rolled cigarette known as a spliff.[235] This is often rolled together while a prayer is offered to Jah; the spliff is lit and smoked only when the prayer is completed.[236] At other times, cannabis is smoked in a water pipe referred to as a chalice: styles include kutchies, chillums, and steamers.[236] The pipe is passed in a counter-clockwise direction around the assembled circle of Rastas.[236]

There are various options that might explain how cannabis smoking came to be part of Rastafari. By the 8th century, Arab traders had introduced cannabis to Central and Southern Africa.[237] In the 19th century, enslaved Bakongo people arrived in Jamaica, where they established the religion of Kumina. In Kumina, cannabis was smoked during religious ceremonies in the belief that it facilitated possession by ancestral spirits.[208] The religion was largely practiced in south-east Jamaica's Saint Thomas Parish, where a prominent early Rasta, Leonard Howell, lived while he was developing many of Rastafari's beliefs and practices; it may have been through Kumina that cannabis became part of Rastafari.[208] A second possible source was the use of cannabis in Hindu rituals.[238] Hindu migrants arrived in Jamaica as indentured servants from British India between 1834 and 1917, and brought cannabis with them.[208] A Jamaican Hindu priest, Laloo, was one of Howell's spiritual advisors, and may have influenced his adoption of ganja.[208] The adoption of cannabis may also have been influenced by the widespread medicinal and recreational use of cannabis among Afro-Jamaicans in the early 20th century.[208] Early Rastafarians may have taken an element of Jamaican culture which they associated with their peasant past and the rejection of capitalism and sanctified it by according it Biblical correlates.[239]

In many countries—including Jamaica[240]—cannabis is illegal and by using it, Rastas protest the rules and regulations of Babylon.[241] In the United States, for example, thousands of practitioners have been arrested because of their possession of the drug.[242] Rastas have also advocated for the legalisation of cannabis in those jurisdictions where it is illegal;[243] in 2015, Jamaica decriminalized personal possession of marijuana up to two ounces and legalized it for medicinal and scientific purposes.[244] In 2019, Barbados legalised Rastafari use of cannabis within religious settings and pledged 60 acres (24 ha) of land for Rastafari to grow it.[245][246]

Music

Rastafari music developed at reasoning sessions,[247] where drumming, chanting, and dancing are all present.[248] Rasta music is performed to praise and commune with Jah,[249] and to reaffirm the rejection of Babylon.[249] Rastas believe that their music has healing properties, with the ability to cure colds, fevers, and headaches.[249] Many of these songs are sung to the tune of older Christian hymns,[250] but others are original Rasta creations.[249]

The bass-line of Rasta music is provided by the akete, a three-drum set, which is accompanied by percussion instruments like rattles and tambourines.[248] A syncopated rhythm is then provided by the fundeh drum.[248] In addition, a peta drum improvises over the rhythm.[248] The different components of the music are regarded as displaying different symbolism; the bassline symbolises blows against Babylon, while the lighter beats denote hope for the future.[248]

As Rastafari developed, popular music became its chief communicative medium.[251] During the 1960s, ska was a popular musical style in Jamaica, and although its protests against social and political conditions were mild, it gave early expression to Rasta socio-political ideology.[252] Particularly prominent in the connection between Rastafari and ska were the musicians Count Ossie and Don Drummond.[253] Ossie was a drummer who believed that black people needed to develop their own style of music;[254] he was heavily influenced by Burru, an Afro-Jamaican drumming style.[255] Ossie subsequently popularised this new Rastafari ritual music by playing at various groundings and groundations around Jamaica,[255] with songs like "Another Moses" and "Babylon Gone" reflecting Rasta influence.[256] Rasta themes also appeared in Drummond's work, with songs such as "Reincarnation" and "Tribute to Marcus Garvey".[256]

1968 saw the development of reggae in Jamaica, a musical style typified by slower, heavier rhythms than ska and the increased use of Jamaican Patois.[257] Like calypso, reggae was a medium for social commentary,[258] although it demonstrated a wider use of radical political and Rasta themes than were previously present in Jamaican popular music.[257] Reggae artists incorporated Rasta ritual rhythms, and also adopted Rasta chants, language, motifs, and social critiques.[259] Songs like The Wailers' "African Herbsman" and Peter Tosh's "Legalize It" referenced cannabis use,[260] while tracks like The Melodians' "Rivers of Babylon" and Junior Byles' "Beat Down Babylon" referenced Rasta beliefs in Babylon.[261] Reggae gained widespread international popularity during the mid-1970s,[262] coming to be viewed by black people in many different countries as music of the oppressed.[263] Many Rastas grew critical of reggae, believing that it had commercialised their religion.[264] Although reggae contains much Rastafari symbolism,[5] and the two are widely associated,[265] the connection is often exaggerated by non-Rastas.[266] Most Rastas do not listen to reggae music,[266] and reggae has also been utilised by other religious groups, such as Protestant Evangelicals.[267] Out of reggae came dub music; dub artists often employ Rastafari terminology, even when not Rastas themselves.[268] In the mid to late 1990s, Jungle music became popular among Rastas in the United Kingdom with Rebel MC (Congo Natty) being the most notable Rasta artist with his album “Tribute to Haile Selassie I”.[269]

Language and symbolism

Rastas typically regard words as having an intrinsic power,[270] seeking to avoid language that contributes to servility, self-degradation, and the objectification of the person.[271] Practitioners therefore often use their own form of language, known commonly as "dread talk",[272] "Iyaric",[273] and "Rasta talk".[274] Developed in Jamaica during the 1940s,[275] this use of language fosters group identity and cultivates particular values.[276] Adherents believe that by formulating their own language they are launching an ideological attack on the integrity of the English language, which they view as a tool of Babylon.[277] The use of this language helps Rastas distinguish and separate themselves from non-Rastas,[278] for whom—according to Barrett—Rasta rhetoric can be "meaningless babbling".[279] However, Rasta terms have also filtered into wider Jamaican speech patterns.[280]

.svg.png.webp)

Rastas make wide use of the pronoun "I".[281] This denotes the Rasta view that the self is divine,[282] and reminds each Rasta that they are not a slave and have value, worth, and dignity as a human being.[283] For instance, Rastas use "I" in place of "me", "I and I" in place of "we", "I-ceive" in place of "receive", "I-sire" in place of "desire", "I-rate" in place of "create", and "I-men" in place of "Amen".[276] Rastas refer to this process as "InI Consciousness" or "Isciousness".[90] Rastas typically refer to Haile Selassie as "Haile Selassie I", thus indicating their belief in his divinity.[283] Rastas also typically believe that the phonetics of a word should be linked to its meaning.[270] For instance, Rastas often use the word "downpression" in place of "oppression" because oppression bears down on people rather than lifting them up, with "up" being phonetically akin to "opp-".[284] Similarly, they often favour "livicate" over "dedicate" because "ded-" is phonetically akin to the word "dead".[285] In the early decades of the religion's development, Rastas often said "Peace and Love" as a greeting, although the use of this declined as Rastafari matured.[286]

Rastas often make use of the colours red, black, green, and gold.[287] Red, gold, and green were used in the Ethiopian flag, while, prior to the development of Rastafari, the Jamaican black nationalist activist Marcus Garvey had used red, green, and black as the colours for the Pan-African flag representing his United Negro Improvement Association.[288] According to Garvey, the red symbolised the blood of martyrs, the black symbolised the skin of Africans, and the green represented the vegetation of the land, an interpretation endorsed by some Rastas.[289] The colour gold is often included alongside Garvey's three colours; it has been adopted from the Jamaican flag,[290] and is often interpreted as symbolising the minerals and raw materials which constitute Africa's wealth.[291] Rastas often paint these colours onto their buildings, vehicles, kiosks, and other items,[287] or display them on their clothing, helping to distinguish Rastas from non-Rastas and allowing adherents to recognise their co-religionists.[292] As well as being used by Rastas, the colour set has also been adopted by Pan-Africanists more broadly, who use it to display their identification with Afrocentricity;[291] for this reason it was adopted on the flags of many post-independence African states.[287] Rastas often accompany the use of these three or four colours with the image of the Lion of Judah, also adopted from the Ethiopian flag and symbolizing Haile Selassie.[287]

Diet

Rastas seek to produce food "naturally",[152] eating what they call ital, or "natural" food.[293] This is often grown organically,[294] and locally.[270] Most Rastas adhere to the dietary laws outlined in the Book of Leviticus, and thus avoid eating pork or crustaceans.[295] Other Rastas remain vegetarian,[296] or vegan,[297] a practice stemming from their interpretation of Leviticus.[lower-alpha 6][298] Many also avoid the addition of additives, including sugar and salt, to their food.[299] Rasta dietary practices have been ridiculed by non-Rastas; in Ghana for example, where food traditionally includes a high meat content, the Rastas' emphasis on vegetable produce has led to the joke that they "eat like sheep and goats".[300] In Jamaica, Rasta practitioners have commercialised ital food, for instance by selling fruit juices prepared according to Rasta custom.[301]

Rastafarians typically avoid food produced by non-Rastas or from unknown sources.[302] Rasta men refuse to eat food prepared by a woman while she is menstruating,[303] and some will avoid food prepared by a woman at any time.[304] Rastas also generally avoid alcohol,[305] cigarettes,[306] and hard drugs such as heroin and cocaine,[233] presenting these substances as unnatural and dirty and contrasting them with cannabis.[242] Rastas also often avoid mainstream scientific medicine and will reject surgery, injections, or blood transfusions.[307] Instead they utilise herbal medicine for healing, especially teas and poultices, with cannabis often used as an ingredient.[308]

Appearance

Rastas use their physical appearance as a means of visually demarcating themselves from non-Rastas.[106] Male practitioners will often grow long beards,[309] and many Rastas prefer to wear African styles of clothing, such as dashikis, rather than styles that originated in Western countries.[310] However, it is the formation of hair into dreadlocks that is one of the most recognisable Rasta symbols.[311] Rastas believe that dreadlocks are promoted in the Bible, specifically in the Book of Numbers,[lower-alpha 7][312] and regard them as a symbol of strength linked to the hair of the Biblical figure of Samson.[313] They argue that their dreadlocks mark a covenant that they have made with Jah,[314] and reflect their commitment to the idea of 'naturalness'.[315] They also perceive the wearing of dreads as a symbolic rejection of Babylon and a refusal to conform to its norms regarding grooming aesthetics.[316] Rastas are often critical of black people who straighten their hair, believing that it is an attempt to imitate white European hair and thus reflects alienation from a person's African identity.[315] Sometimes this dreadlocked hair is then shaped and styled, often inspired by a lion's mane symbolising Haile Selassie, who is regarded as "the Conquering Lion of Judah".[317]

Rastas differ on whether they regard dreadlocks as compulsory for practicing the religion.[24] Some Rastas do not wear their hair in dreadlocks; within the religion they are often termed "cleanface" Rastas,[318] with those wearing dreadlocked hair often called "locksmen".[319] Some Rastas have also joined the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the Christian organisation to which Haile Selassie belonged, and these individuals are forbidden from putting their hair in dreadlocks by the Church.[320] In reference to Rasta hairstyles, Rastas often refer to non-Rastas as "baldheads",[321] or "combsome",[322] while those who are new to Rastafari and who have only just started to grow their hair into dreads are termed "nubbies".[318] Members of the Bobo Ashanti sect of Rastas conceal their dreadlocks within turbans,[323] while some Rastas tuck their dreads under a rastacap or tam headdress, usually coloured green, red, black, and yellow.[324] Dreadlocks and Rastafari-inspired clothing have also been worn for aesthetic reasons by non-Rastas.[325] For instance, many reggae musicians who do not adhere to the Rastafari religion wear their hair in dreads.[266]

From the beginning of the Rastafari movement in the 1930s, adherents typically grew beards and tall hair, perhaps in imitation of Haile Selassie.[128] The wearing of hair as dreadlocks then emerged as a Rasta practice in the 1940s;[128] there were debates within the movement as to whether dreadlocks should be worn or not, with proponents of the style becoming dominant.[326] There are various claims as to how this practice was adopted.[128] One claim is that it was adopted in imitation of certain African nations, such as the Maasai, Somalis, or Oromo, or that it was inspired by the hairstyles worn by some of those involved in the anti-colonialist Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya.[128] An alternative explanation is that it was inspired by the hairstyles of the Hindu sadhus.[327]

The wearing of dreadlocks has contributed to negative views of Rastafari among non-Rastas, many of whom regard it as wild and unattractive.[328] Dreadlocks remain socially stigmatised in many societies; in Ghana for example, they are often associated with the homeless and mentally ill, with such associations of marginality extending onto Ghanaian Rastas.[329] In Jamaica during the mid-20th century, teachers and police officers used to forcibly cut off the dreads of Rastas.[330] In various countries, Rastas have since won legal battles ensuring their right to wear dreadlocks: in 2020, for instance, the High Court of Malawi ruled that all public schools must allow their students to wear dreadlocks.[331]

History

Rastafari developed out of the legacy of the Atlantic slave trade, in which over ten million enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries.[332] Under 700,000 of these slaves were settled in the British colony of Jamaica.[332] The British government abolished slavery in the Caribbean island in 1834,[333] although racial prejudice remained prevalent across Jamaican society.[334]

Ethiopianism, Back to Africa, and Marcus Garvey

.jpg.webp)

Rastafari owed much to intellectual frameworks arising in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[335] One key influence on Rastafari was Christian Revivalism,[336] with the Great Revival of 1860–61 drawing many Afro-Jamaicans to join churches.[337] Increasing numbers of Pentecostal missionaries from the United States arrived in Jamaica during the early 20th century, climaxing in the 1920s.[338]

Further contributing significantly to Rastafari's development were Ethiopianism and the Back to Africa ethos, both traditions with 18th-century roots.[339] In the 19th century, there were growing calls for the African diaspora located in Western Europe and the Americas to be resettled in Africa,[339] with some of this diaspora establishing colonies in Sierra Leone and Liberia.[339] Based in Liberia, the black Christian preacher Edward Wilmot Blyden began promoting African pride and the preservation of African tradition, customs, and institutions.[340] Also spreading throughout Africa was Ethiopianism, a movement that accorded special status to the east African nation of Ethiopia because it was mentioned in various Biblical passages.[341] For adherents of Ethiopianism, "Ethiopia" was regarded as a synonym of Africa as a whole.[342]

Of significant influence on Rastafari was the Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey, who spent much of his adult life in the US and Britain. Garvey supported the idea of global racial separatism and called for part of the African diaspora to relocate to Africa.[343] His ideas faced opposition from civil rights activists like W. E. B. Du Bois who supported racial integration,[344] and as a mass movement, Garveyism declined in the Great Depression of the 1930s.[344] A rumour later spread that in 1916, Garvey had called on his supporters to "look to Africa" for the crowning of a black king; this quote was never verified.[345] However, in August 1930, Garvey's play, Coronation of an African King, was performed in Kingston. Its plot revolved around the crowning of the fictional Prince Cudjoe of Sudan, although it anticipated the crowning of Haile Selassie later that year.[346] Rastas hold Garvey in great esteem,[115] with many regarding him as a prophet.[347] Garvey knew of Rastafari, but took a largely negative view of the religion;[348] he also became a critic of Haile Selassie,[349] calling him "a great coward" who rules a "country where black men are chained and flogged".[83]

Haile Selassie and the early Rastas: 1930–1949

Haile Selassie was crowned Emperor of Ethiopia in 1930, becoming the first sovereign monarch crowned in Sub-Saharan Africa since 1891 and first Christian one since 1889. A number of Jamaica's Christian clergymen claimed that Selassie's coronation was evidence that he was the black messiah that they believed was prophesied in the Book of Revelation,[lower-alpha 8] the Book of Daniel,[lower-alpha 9] and Psalms.[lower-alpha 10][350] Over the following years, several street preachers—most notably Leonard Howell, Archibald Dunkley, Robert Hinds, and Joseph Hibbert—began claiming that Haile Selassie was the returned Jesus.[351] They first did so in Kingston, and soon the message spread throughout 1930s Jamaica,[352] especially among poor communities who were hit particularly hard by the Great Depression.[162] Clarke stated that "to all intents and purposes this was the beginning" of the Rastafari movement.[353]

Howell has been described as the "leading figure" in the early Rastafari movement.[30] He preached that black Africans were superior to white Europeans and that Afro-Jamaicans should owe their allegiance to Haile Selassie rather than to George V, King of Great Britain and Ireland. The island's British authorities arrested him and charged him with sedition in 1934, resulting in his two-year imprisonment.[354] Following his release, Howell established the Ethiopian Salvation Society and in 1939 established a Rasta community, known as Pinnacle, in Saint Catherine Parish.[355] Police feared that Howell was training his followers for an armed rebellion and were angered that it was producing cannabis for sale. They raided the community on several occasions and Howell was imprisoned for a further two years.[356] Upon his release he returned to Pinnacle, but the police continued with their raids and shut down the community in 1954; Howell himself was committed to a mental hospital.[357]

In 1936, Italy invaded and occupied Ethiopia, and Haile Selassie went into exile. The invasion brought international condemnation and led to growing sympathy for the Ethiopian cause.[358] In 1937, Selassie created the Ethiopian World Federation, which established a branch in Jamaica later that decade.[359] In 1941, the British drove the Italians out of Ethiopia and Selassie returned to reclaim his throne. Many Rastas interpreted this as the fulfilment of a prophecy made in the Book of Revelation.[lower-alpha 11][358]

Growing visibility: 1950–1969

Rastafari's main appeal was among the lower classes of Jamaican society.[358] For its first thirty years, Rastafari was in a conflictual relationship with the Jamaican authorities.[360] Jamaica's Rastas expressed contempt for many aspects of the island's society, viewing the government, police, bureaucracy, professional classes, and established churches as instruments of Babylon.[159] Relations between practitioners and the police were strained, with Rastas often being arrested for cannabis possession.[361] During the 1950s the movement grew rapidly in Jamaica itself and also spread to other Caribbean islands, the United States, and the United Kingdom.[358]

In the 1940s and 1950s, a more militant brand of Rastafari emerged.[362] The vanguard of this was the House of Youth Black Faith, a group whose members were largely based in West Kingston.[363] Backlash against the Rastas grew after a practitioner of the religion allegedly killed a woman in 1957.[159] In March 1958, the first Rastafarian Universal Convention was held in the settlement of Back-o-Wall, Kingston.[364] Following the event, militant Rastas unsuccessfully tried to capture the city in the name of Haile Selassie.[365] Later that year they tried again in Spanish Town.[159] The increasing militancy of some Rastas resulted in growing alarm about the religion in Jamaica.[159] According to Cashmore, the Rastas became "folk devils" in Jamaican society.[366] In 1959, the self-declared prophet and founder of the African Reform Church, Claudius Henry, sold thousands of tickets to Afro-Jamaicans, including many Rastas, for passage on a ship that he claimed would take them to Africa. The ship never arrived and Henry was charged with fraud. In 1960 he was sentenced to six years imprisonment for conspiring to overthrow the government.[367] Henry's son was accused of being part of a paramilitary cell and executed, confirming public fears about Rasta violence.[368] One of the most prominent clashes between Rastas and law enforcement was the Coral Gardens incident of 1963, in which an initial skirmish between police and Rastas resulted in several deaths and led to a larger roundup of practitioners.[369] Clamping down on the Rasta movement, in 1964 the island's government implemented tougher laws surrounding cannabis use.[370]

At the invitation of Jamaica's government, Haile Selassie visited the island for the first time on 21 April 1966, with thousands of Rastas assembled in the crowd waiting to meet him at the airport.[371] The event was the high point of their discipleship for many of the religion's members.[372] Over the course of the 1960s, Jamaica's Rasta community underwent a process of routinisation,[373] with the late 1960s witnessing the launch of the first official Rastafarian newspaper, the Rastafarian Movement Association's Rasta Voice.[374] The decade also saw Rastafari develop in increasingly complex ways,[372] as it did when some Rastas began to reinterpret the idea that salvation required a physical return to Africa, instead interpreting salvation as coming through a process of mental decolonisation that embraced African approaches to life.[372]

Whereas its membership had previously derived predominantly from poorer sectors of society, in the 1960s Rastafari began attracting support from more privileged groups like students and professional musicians.[375] The foremost group emphasising this approach was the Twelve Tribes of Israel, whose members came to be known as "Uptown Rastas".[376] Among those attracted to Rastafari in this decade were middle-class intellectuals like Leahcim Semaj, who called for the religious community to place greater emphasis on scholarly social theory as a method of achieving change.[377] Although some Jamaican Rastas were critical of him,[378] many came under the influence of the Guyanese black nationalist academic Walter Rodney, who lectured to their community in 1968 before publishing his thoughts as the pamphlet Groundings.[379] Like Rodney, many Jamaican Rastas were influenced by the U.S.-based Black Power movement.[380] After Black Power declined following the deaths of prominent exponents such as Malcolm X, Michael X, and George Jackson, Rastafari filled the vacuum it left for many black youth.[381]

International spread and decline: 1970–present

In the mid-1970s, reggae's international popularity exploded.[262] The most successful reggae artist was Bob Marley, who—according to Cashmore—"more than any other individual, was responsible for introducing Rastafarian themes, concepts and demands to a truly universal audience".[382] Reggae's popularity led to a growth in "pseudo-Rastafarians", individuals who listened to reggae and wore Rasta clothing but did not share its belief system.[383] Many Rastas were angered by this, believing it commercialised their religion.[264]

Through reggae, Rasta musicians became increasingly important in Jamaica's political life during the 1970s.[384] To bolster his popularity with the electorate, Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley employed Rasta imagery and courted and obtained support from Marley and other reggae musicians.[385] Manley described Rastas as a "beautiful and remarkable people"[328] and carried a cane, the "rod of correction", which he claimed was a gift from Haile Selassie.[386] Following Manley's example, Jamaican political parties increasingly employed Rasta language, symbols, and reggae references in their campaigns,[387] while Rasta symbols became increasingly mainstream in Jamaican society.[388] This helped to confer greater legitimacy on Rastafari,[389] with reggae and Rasta imagery being increasingly presented as a core part of Jamaica's cultural heritage for the growing tourist industry.[390] In the 1980s, a Rasta, Barbara Makeda Blake Hannah, became a senator in the Jamaican Parliament.[391]

Enthusiasm for Rastafari was likely dampened by the death of Haile Selassie in 1975 and that of Marley in 1981.[392] During the 1980s, the number of Rastas in Jamaica declined,[393] with Pentecostal and other Charismatic Christian groups proving more successful at attracting young recruits.[394] Several publicly prominent Rastas converted to Christianity,[394] and two of those who did so—Judy Mowatt and Tommy Cowan—maintained that Marley had converted from Rastafari to Christianity, in the form of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, during his final days.[395] The significance of Rastafari messages in reggae also declined with the growing popularity of dancehall, a Jamaican musical genre that typically foregrounded lyrical themes of hyper-masculinity, violence, and sexual activity rather than religious symbolism.[396]

The mid-1990s saw a revival of Rastafari-focused reggae associated with musicians like Anthony B, Buju Banton, Luciano, Sizzla, and Capleton.[396] From the 1990s, Jamaica also witnessed the growth of organised political activity within the Rasta community, seen for instance through campaigns for the legalisation of cannabis and the creation of political parties like the Jamaican Alliance Movement and the Imperial Ethiopian World Federation Incorporated Political Party, none of which attained more than minimal electoral support.[397] In 1995, the Rastafari Centralization Organization was established in Jamaica as an attempt to organise the Rastafari community.[398]

Organisation

Rastafari is not a homogeneous movement and has no single administrative structure,[399] nor any single leader.[400] A majority of Rastas avoid centralised and hierarchical structures because they do not want to replicate the structures of Babylon and because their religion's ultra-individualistic ethos places emphasis on inner divinity.[401] The structure of most Rastafari groups is less like that of Christian denominations and is instead akin to the cellular structure of other African diasporic traditions like Haitian Vodou, Cuban Santería, and Jamaica's Revival Zion.[399] Since the 1970s, there have been attempts to unify all Rastas, namely through the establishment of the Rastafari Movement Association, which sought political mobilisation.[402] In 1982, the first international assembly of Rastafari groups took place in Toronto, Canada.[402] This and subsequent international conferences, assemblies, and workshops have helped to cement global networks and cultivate an international community of Rastas.[403]

Mansions of Rastafari

Sub-divisions of Rastafari are often referred to as "houses" or "mansions", in keeping with a passage from the Gospel of John (14:2): as translated in the King James Bible, Jesus states "In my father's house are many mansions".[404] The three most prominent branches are the House of Nyabinghi, the Bobo Ashanti, and the Twelve Tribes of Israel, although other important groups include the Church of Haile Selassie I, Inc., and the Fulfilled Rastafari.[404] By fragmenting into different houses without any single leader, Rastafari became more resilient amid opposition from Jamaica's government during the early decades of the movement.[405]

Probably the largest Rastafari group, the House of Nyabinghi is an aggregate of more traditional and militant Rastas who seek to retain the movement close to the way in which it existed during the 1940s.[404] They stress the idea that Haile Selassie was Jah and the reincarnation of Jesus.[404] The wearing of dreadlocks is regarded as indispensable and patriarchal gender roles are strongly emphasised,[404] while, according to Cashmore, they are "vehemently anti-white".[406] Nyabinghi Rastas refuse to compromise with Babylon and are often critical of reggae musicians like Marley, whom they regard as having collaborated with the commercial music industry.[407]

The Bobo Ashanti sect was founded in Jamaica by Emanuel Charles Edwards through the establishment of his Ethiopia Africa Black International Congress (EABIC) in 1958.[408] The group established a commune in Bull Bay, where they were led by Edwards until his death in 1994.[409] The group hold to a highly rigid ethos.[410] Edwards advocated the idea of a new trinity, with Haile Selassie as the living God, himself as the Christ, and Garvey as the prophet.[411] Male members are divided into two categories: the "priests" who conduct religious services and the "prophets" who take part in reasoning sessions.[410] It places greater restrictions on women than most other forms of Rastafari;[412] women are regarded as impure because of menstruation and childbirth and so are not permitted to cook for men.[410] The group teaches that black Africans are God's chosen people and are superior to white Europeans,[413] with members often refusing to associate with white people.[414] Bobo Ashanti Rastas are recognisable by their long, flowing robes and turbans.[415]

The Twelve Tribes of Israel group was founded in 1968 in Kingston by Vernon Carrington.[416] He proclaimed himself the reincarnation of the Old Testament prophet Gad and his followers call him "Prophet Gad", "Brother Gad", or "Gadman".[417] It is commonly regarded as the most liberal form of Rastafari and the closest to Christianity.[58] Practitioners are often dubbed "Christian Rastas" because they believe Jesus is the only saviour; Haile Selassie is accorded importance, but is not viewed as the second coming of Jesus.[418] The group divides its members into twelve groups according to which Hebrew calendar month they were born in; each month is associated with a particular colour, body part, and mental function.[419] Maintaining dreadlocks and an ital diet are considered commendable but not essential,[420] while adherents are called upon to read a chapter of the Bible each day.[421] Membership is open to individuals of any racial background.[422]

The Twelve Tribes peaked in popularity during the 1970s, when it attracted artists, musicians, and many middle-class followers—Marley among them[423]—resulting in the terms "middle-class Rastas" and "uptown Rastas" being applied to members of the group.[424] Carrington died in 2005, since which time the Twelve Tribes of Israel have been led by an executive council.[424] As of 2010, it was recorded as being the largest of the centralised Rasta groups.[72] It remains headquartered in Kingston, although it has followers outside Jamaica;[425] the group was responsible for establishing the Rasta community in Shashamane, Ethiopia.[426]

The Church of Haile Selassie, Inc., was founded by Abuna Foxe and operated much like a mainstream Christian church, with a hierarchy of functionaries, weekly services, and Sunday schools.[427] In adopting this broad approach, the Church seeks to develop Rastafari's respectability in wider society.[402] Fulfilled Rastafari is a multi-ethnic movement that has spread in popularity during the 21st century, in large part through the Internet.[402] The Fulfilled Rastafari group accept Haile Selassie's statements that he was a man and that he was a devout Christian, and so place emphasis on worshipping Jesus through the example set forth by Haile Selassie.[402] The wearing of dreadlocks and the adherence to an ital diet are considered issues up to the individual.[402]

Demographics

Born in the ghettos of Kingston, Jamaica, the Rastafarian movement has captured the imagination of thousands of black youth, and some white youth, throughout Jamaica, the Caribbean, Britain, France, and other countries in Western Europe and North America. It is also to be found in smaller numbers in parts of Africa—for example, in Ethiopia, Ghana, and Senegal—and in Australia and New Zealand, particularly among the Maori.

— Sociologist of religion Peter B. Clarke, 1986[98]

As of 2012, there were an estimated 700,000 to 1,000,000 Rastas worldwide.[428] They can be found in many different regions, including most of the world's major population centres.[428] Rastafari's influence on wider society has been more substantial than its numerical size,[429] particularly in fostering a racial, political, and cultural consciousness among the African diaspora and Africans themselves.[428] Men dominate Rastafari.[430] In its early years, most of its followers were men, and the women who did adhere to it tended to remain in the background.[430] This picture of Rastafari's demographics has been confirmed by ethnographic studies conducted in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[431]

The Rasta message resonates with many people who feel marginalised and alienated by the values and institutions of their society.[432] Internationally, it has proved most popular among the poor and among marginalised youth.[433] In valorising Africa and blackness, Rastafari provides a positive identity for youth in the African diaspora by allowing them to psychologically reject their social stigmatisation.[432] It then provides these disaffected people with the discursive stance from which they can challenge capitalism and consumerism, providing them with symbols of resistance and defiance.[432] Cashmore expressed the view that "whenever there are black people who sense an injust disparity between their own material conditions and those of the whites who surround them and tend to control major social institutions, the Rasta messages have relevance."[434]

Conversion and deconversion

Rastafari is a non-missionary religion.[435] However, elders from Jamaica often go "trodding" to instruct new converts in the fundamentals of the religion.[436] On researching English Rastas during the 1970s, Cashmore noted that they had not converted instantaneously, but rather had undergone "a process of drift" through which they gradually adopted Rasta beliefs and practices, resulting in their ultimate acceptance of Haile Selassie's central importance.[437] Based on his research in West Africa, Neil J. Savishinsky found that many of those who converted to Rastafari came to the religion through their pre-existing use of marijuana as a recreational drug.[438]

Rastas often claim that—rather than converting to the religion—they were actually always a Rasta and that their embrace of its beliefs was merely the realisation of this.[439] There is no formal ritual carried out to mark an individual's entry into the Rastafari movement,[440] although once they do join an individual often changes their name, with many including the prefix "Ras".[54] Rastas regard themselves as an exclusive and elite community, membership of which is restricted to those who have the "insight" to recognise Haile Selassie's importance.[441] Practitioners thus often regard themselves as the "enlightened ones" who have "seen the light".[442] Many of them see no point in establishing good relations with non-Rastas, believing that the latter will never accept Rastafari doctrine as truth.[443]

Some Rastas have left the religion. Clarke noted that among British Rastas, some returned to Pentecostalism and other forms of Christianity, while others embraced Islam or no religion.[444] Some English ex-Rastas described disillusionment when the societal transformation promised by Rastafari failed to appear, while others felt that while Rastafari would be appropriate for agrarian communities in Africa and the Caribbean, it was not suited to industrialised British society.[444] Others experienced disillusionment after developing the view that Haile Selassie had been an oppressive leader of the Ethiopian people.[444] Cashmore found that some British Rastas who had more militant views left the religion after finding its focus on reasoning and music insufficient for the struggle against white domination and racism.[445]

Regional spread

Although it remains most concentrated in the Caribbean,[446] Rastafari has spread to many areas of the world and adapted into many localised variants.[447] It has spread primarily in Anglophone regions and countries, largely because reggae music has primarily been produced in the English language.[433] It is thus most commonly found in the Anglophone Caribbean, United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, and Anglophone parts of Africa.[448]

Jamaica and the Americas

Barrett described Rastafari as "the largest, most identifiable, indigenous movement in Jamaica."[5] In the mid-1980s, there were approximately 70,000 members and sympathisers of Rastafari in Jamaica.[449] The majority were male, working-class, former Christians aged between 18 and 40.[449] In the 2011 Jamaican census, 29,026 individuals identified as Rastas.[450] Jamaica's Rastas were initially entirely from the Afro-Jamaican majority,[451] and although Afro-Jamaicans are still the majority, Rastafari has also gained members from the island's Chinese, Indian, Afro-Chinese, Afro-Jewish, mulatto, and white minorities.[452] Until 1965 the vast majority were from the lower classes, although it has since attracted many middle-class members; by the 1980s there were Jamaican Rastas working as lawyers and university professors.[453] Jamaica is often valorised by Rastas as the fountain-head of their faith, and many Rastas living elsewhere travel to the island on pilgrimage.[454]

Both through travel between the islands,[455] and through reggae's popularity,[456] Rastafari spread across the eastern Caribbean during the 1970s. Here, its ideas complemented the anti-colonial and Afrocentric views prevalent in countries like Trinidad, Grenada, Dominica, and St Vincent.[457] In these countries, the early Rastas often engaged in cultural and political movements to a greater extent than their Jamaican counterparts had.[458] Various Rastas were involved in Grenada's 1979 New Jewel Movement and were given positions in the Grenadine government until it was overthrown and replaced following the U.S. invasion of 1983.[459] Although Fidel Castro's Marxist–Leninist government generally discouraged foreign influences, Rastafari was introduced to Cuba alongside reggae in the 1970s.[460] Foreign Rastas studying in Cuba during the 1990s connected with its reggae scene and helped to further ground it in Rasta beliefs.[461] In Cuba, most Rastas have been male and from the Afro-Cuban population.[462]

Rastafari was introduced to the United States and Canada with the migration of Jamaicans to continental North America in the 1960s and 1970s.[463] American police were often suspicious of Rastas and regarded Rastafari as a criminal sub-culture.[464] Rastafari also attracted converts from within several Native American communities[447] and picked up some support from white members of the hippie subculture, which was then in decline.[465] In Latin America, small communities of Rastas have also established in Brazil, Panama, and Nicaragua.[448]

Africa

Some Rastas in the African diaspora have followed through with their beliefs about resettlement in Africa, with Ghana and Nigeria being particularly favoured.[466] In West Africa, Rastafari has spread largely through the popularity of reggae,[467] gaining a larger presence in Anglophone areas than their Francophone counterparts.[468] Caribbean Rastas arrived in Ghana during the 1960s, encouraged by its first post-independence president, Kwame Nkrumah, while some native Ghanaians also converted to the religion.[469] The largest congregation of Rastas has been in southern parts of Ghana, around Accra, Tema, and the Cape Coast,[122] although Rasta communities also exist in the Muslim-majority area of northern Ghana.[470] The Rasta migrants' wearing of dreadlocks was akin to that of the native fetish priests, which may have assisted the presentation of these Rastas as having authentic African roots in Ghanaian society.[471] However, Ghanaian Rastas have complained of social ostracism and prosecution for cannabis possession, while non-Rastas in Ghana often consider them to be "drop-outs", "too Western", and "not African enough".[472]

.jpg.webp)

A smaller number of Rastas are found in Muslim-majority countries of West Africa, such as Gambia and Senegal.[473] One West African group that wear dreadlocks are the Baye Faal, a Mouride sect in Senegambia, some of whose practitioners have started calling themselves "Rastas" in reference to their visual similarity to Rastafari.[474] The popularity of dreadlocks and marijuana among the Baye Faal may have been spread in large part through access to Rasta-influenced reggae in the 1970s.[475] A small community of Rastas also appeared in Burkina Faso.[476]