Bangladesh

Bangladesh (/ˌbæŋɡləˈdɛʃ, ˌbɑːŋ-/;[12] Bengali: বাংলাদেশ, pronounced [ˈbaŋlaˌdeʃ] (![]() listen)), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of 148,460 square kilometres (57,320 sq mi).[7] Bangladesh is among the most densely populated countries in the world, and shares land borders with India to the west, north, and east, and Myanmar to the southeast; to the south it has a coastline along the Bay of Bengal. It is narrowly separated from Bhutan and Nepal by the Siliguri Corridor; and from China by the Indian state of Sikkim in the north. Dhaka, the capital and largest city, is the nation's political, financial and cultural center. Chittagong, the second-largest city, is the busiest port on the Bay of Bengal. The official language is Bengali, one of the easternmost branches of the Indo-European language family.

listen)), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of 148,460 square kilometres (57,320 sq mi).[7] Bangladesh is among the most densely populated countries in the world, and shares land borders with India to the west, north, and east, and Myanmar to the southeast; to the south it has a coastline along the Bay of Bengal. It is narrowly separated from Bhutan and Nepal by the Siliguri Corridor; and from China by the Indian state of Sikkim in the north. Dhaka, the capital and largest city, is the nation's political, financial and cultural center. Chittagong, the second-largest city, is the busiest port on the Bay of Bengal. The official language is Bengali, one of the easternmost branches of the Indo-European language family.

People's Republic of Bangladesh

| |

|---|---|

Emblem

| |

| Anthem: "Amar Sonar Bangla" (Bengali) "My Golden Bengal" | |

| Official Seal of the Government of Bangladesh | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital and largest city | Dhaka 23°45′50″N 90°23′20″E |

| Official language and national language | Bengali[4] |

| Ethnic groups (2022[5]) |

|

| Religion (2022 census[6]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Bangladeshi |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party parliamentary republic |

• President | Abdul Hamid |

• Prime Minister | Sheikh Hasina |

• House Speaker | Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury |

• Chief Justice | Hasan Foez Siddique |

| Legislature | Jatiya Sangsad |

| Independence from Pakistan | |

• Declared | 26 March 1971 |

• Victory Day | 16 December 1971 |

• Current Constitution | 16 December 1972 |

| Area | |

• Total | 148,460[7] km2 (57,320 sq mi) (92nd[7]) |

• Water (%) | 6.4 |

• Land area | 130,170 km2[7] |

• Water area | 18,290 km2[7] |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 165,158,616[8] (8th) |

• Density | 1,106/km2 (2,864.5/sq mi) (7th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 129th |

| Currency | Taka (৳) (BDT) |

| Time zone | UTC+6 (BST) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +880 |

| ISO 3166 code | BD |

| Internet TLD | .bd .বাংলা |

Bangladesh forms the sovereign part of the historic and ethnolinguistic region of Bengal, which was divided during the Partition of India in 1947.[13] The country has a Bengali Muslim majority. Ancient Bengal was an important cultural centre in the Indian subcontinent as the home of the states of Vanga, Pundra, Gangaridai, Gauda, Samatata, and Harikela. The Mauryan, Gupta, Pala, Sena, Chandra and Deva dynasties were the last pre-Islamic rulers of Bengal. The Muslim conquest of Bengal began in 1204 when Bakhtiar Khalji overran northern Bengal and invaded Tibet. Becoming part of the Delhi Sultanate, three city-states emerged in the 14th century with much of eastern Bengal being ruled from Sonargaon. Sufi missionary leaders like Sultan Balkhi, Shah Jalal and Shah Makhdum Rupos helped in spreading Muslim rule. The region was unified into an independent, unitary Bengal Sultanate. Under Mughal rule, eastern Bengal continued to prosper as the melting pot of Muslims in the eastern subcontinent and attracted traders from around the world. The Bengali elite were among the richest people in the world due to strong trade networks like the muslin trade which supplied textiles, such as 40% of Dutch imports from Asia.[14] Mughal Bengal became increasingly assertive and independent under the Nawabs of Bengal in the 18th century. In 1757, the betrayal of Mir Jafar resulted in the defeat of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah to the British East India Company and eventual British dominance across South Asia. The Bengal Presidency grew into the largest administrative unit in British India. The creation of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905 set a precedent for the emergence of Bangladesh. In 1940, the first Prime Minister of Bengal supported the Lahore Resolution with the hope of creating a state in the eastern subcontinent. Prior to the partition of Bengal, the Prime Minister of Bengal proposed a Bengali sovereign state. A referendum and the announcement of the Radcliffe Line established the present-day territorial boundary of Bangladesh.

In 1947, East Bengal became the most populous province in the Dominion of Pakistan. It was renamed as East Pakistan with Dhaka becoming the country's legislative capital. The Bengali Language Movement in 1952; the East Bengali legislative election, 1954; the 1958 Pakistani coup d'état; the Six point movement of 1966; and the 1970 Pakistani general election resulted in the rise of Bengali nationalism and pro-democracy movements in East Pakistan. The refusal of the Pakistani military junta to transfer power to the Awami League led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman led to the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, in which the Mukti Bahini aided by India waged a successful armed revolution. The conflict saw the 1971 Bangladesh genocide and the massacre of pro-independence Bengali civilians, including intellectuals. The new state of Bangladesh became the first constitutionally secular state in South Asia in 1972.[15] Islam was declared the state religion in 1988.[16][17][18] In 2010, the Bangladesh Supreme Court reaffirmed secular principles in the constitution.[19]

A middle power in the Indo-Pacific,[20] Bangladesh is the second largest economy in South Asia. It maintains the third-largest military in the region and is a major contributor to UN peacekeeping operations. The large Muslim population of Bangladesh makes it the third-largest Muslim-majority country. Bangladesh is a unitary parliamentary constitutional republic based on the Westminster system. Bengalis make up 99% of the total population of Bangladesh.[21] The country consists of 8 divisions, 64 districts and 495 subdistricts.[22] It hosts one of the largest refugee populations in the world due to the Rohingya genocide.[23] Bangladesh faces many challenges, particularly effects of climate change.[24] Bangladesh has been a leader within the Climate Vulnerable Forum. It hosts the headquarters of BIMSTEC. It is a founding member of SAARC, as well as a member of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and the Commonwealth of Nations.

Etymology

The etymology of Bangladesh ("Bengali Country") can be traced to the early 20th century, when Bengali patriotic songs, such as Namo Namo Namo Bangladesh Momo by Kazi Nazrul Islam and Aaji Bangladesher Hridoy by Rabindranath Tagore, used the term.[25] The term Bangladesh was often written as two words, Bangla Desh, in the past. Starting in the 1950s, Bengali nationalists used the term in political rallies in East Pakistan. The term Bangla is a major name for both the Bengal region and the Bengali language. The origins of the term Bangla are unclear, with theories pointing to a Bronze Age proto-Dravidian tribe,[26] the Austric word "Bonga" (Sun god),[27] and the Iron Age Vanga Kingdom.[27] The earliest known usage of the term is the Nesari plate in 805 AD. The term Vangaladesa is found in 11th-century South Indian records.[28][29] The term gained official status during the Sultanate of Bengal in the 14th century.[30][31] Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah proclaimed himself as the first "Shah of Bangala" in 1342.[30] The word Bangāl became the most common name for the region during the Islamic period.[32] 16th-century historian Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak mentions in his Ain-i-Akbari that the addition of the suffix "al" came from the fact that the ancient rajahs of the land raised mounds of earth 10 feet high and 20 in breadth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al".[33] This is also mentioned in Ghulam Husain Salim's Riyaz-us-Salatin.[34] The Indo-Aryan suffix Desh is derived from the Sanskrit word deśha, which means "land" or "country". Hence, the name Bangladesh means "Land of Bengal" or "Country of Bengal".[29]

History

Ancient Bengal

Stone Age tools found in Bangladesh indicate human habitation for over 20,000 years,[35] and remnants of Copper Age settlements date back 4,000 years.[35] Ancient Bengal was settled by Austroasiatics, Tibeto-Burmans, Dravidians and Indo-Aryans in consecutive waves of migration.[35][36] Archaeological evidence confirms that by the second millennium BCE, rice-cultivating communities inhabited the region. By the 11th century people lived in systemically aligned housing, buried their dead, and manufactured copper ornaments and black and red pottery.[37] The Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers were natural arteries for communication and transportation,[37] and estuaries on the Bay of Bengal permitted maritime trade. The early Iron Age saw the development of metal weaponry, coinage, agriculture and irrigation.[37] Major urban settlements formed during the late Iron Age, in the mid-first millennium BCE,[38] when the Northern Black Polished Ware culture developed.[39] In 1879, Alexander Cunningham identified Mahasthangarh as the capital of the Pundra Kingdom mentioned in the Rigveda.[40][41] The oldest inscription in Bangladesh was found in Mahasthangarh and dates from the 3rd century BCE. It is written in the Brahmi script.[42]

Greek and Roman records of the ancient Gangaridai Kingdom, which (according to legend) deterred the invasion of Alexander the Great, are linked to the fort city in Wari-Bateshwar.[43][44] The site is also identified with the prosperous trading centre of Souanagoura listed on Ptolemy's world map.[45] Roman geographers noted a large seaport in southeastern Bengal, corresponding to the present-day Chittagong region.[46]

Ancient Buddhist and Hindu states which ruled Bangladesh included the Vanga, Samatata and Pundra kingdoms, the Mauryan and Gupta Empires, the Varman dynasty, Shashanka's kingdom, the Khadga and Candra dynasties, the Pala Empire, the Sena dynasty, the Harikela kingdom and the Deva dynasty. These states had well-developed currencies, banking, shipping, architecture, and art, and the ancient universities of Bikrampur and Mainamati hosted scholars and students from other parts of Asia. Xuanzang of China was a noted scholar who resided at the Somapura Mahavihara (the largest monastery in ancient India), and Atisa travelled from Bengal to Tibet to preach Buddhism. The earliest form of the Bengali language emerged during the eighth century. Seafarers in the Bay of Bengal were modern Bangladesh is now located in, have also been sailing and trading with Southeast Asia[47] and exported Buddhist and Hindu cultures to the region since the early Christian era.[48]

Islamic Bengal

The early history of Islam in Bengal is divided into two phases. The first phase is the period of maritime trade with Arabia and Persia between the 8th and 12th centuries. The second phase covers centuries of Muslim dynastic rule after the Islamic conquest of Bengal. The writings of Al-Idrisi, Ibn Hawqal, Al-Masudi, Ibn Khordadbeh and Sulaiman record the maritime links between Arabia, Persia and Bengal.[50] Muslim trade with Bengal flourished after the fall of the Sasanian Empire and the Arab takeover of Persian trade routes. Much of this trade occurred with southeastern Bengal in areas east of the Meghna River. There is speculation regarding the presence of a Muslim community in Bangladesh as early as 690 CE; this is based on the discovery of one of South Asia's oldest mosques in northern Bangladesh.[51][52][50] Bengal was possibly used as a transit route to China by the earliest Muslims. Abbasid coins have been discovered in the archaeological ruins of Paharpur and Mainamati.[53] A collection of Sasanian, Umayyad and Abbasid coins are preserved in the Bangladesh National Museum.[54]

The Muslim conquest of Bengal began with the 1204 Ghurid expeditions led by Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, who overran the Sena capital in Gauda and led the first Muslim army into Tibet.[37] The conquest of Bengal was inscribed in gold coins of the Delhi Sultanate. Bengal was ruled by the Sultans of Delhi for a century under the Mamluk, Balban, and Tughluq dynasties. In the 14th century, three city-states emerged in Bengal, including Sonargaon led by Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah, Satgaon led by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah and Lakhnauti led by Alauddin Ali Shah. These city-states were led by former governors who declared independence from Delhi. The Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta visited eastern Bengal during the reign of Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah. Ibn Battuta also visited the Sufi leader Shah Jalal in Sylhet. Sufis played an important role in spreading Islam in Bengal through both peaceful conversion and militarily overthrowing pre-Islamic rulers. In 1352, Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah united the three city-states into a single, unitary and independent Bengal Sultanate. The new Sultan of Bengal led the first Muslim army into Nepal and forced the Sultan of Delhi to retreat during an invasion. The army of Ilyas Shah reached as far as Varanasi in the northwest, Kathmandu in the north, Kamarupa in the east and Orissa in the south. Ilyas Shah raided many of these areas and returned to Bengal with treasures. During the reign of Sikandar Shah, Delhi recognized Bengal's independence. The Bengal Sultanate established a network of mint towns which acted as a provincial capitals where the Sultan's currency was minted.[55] Bengal became the eastern frontier of the Islamic world, which stretched from Muslim Spain in the west to Bengal in the east. The Bengali language crystallized as an official court language during the Bengal Sultanate, with prominent writers like Nur Qutb Alam, Usman Serajuddin, Alaul Haq, Alaol, Shah Muhammad Sagir, Abdul Hakim and Syed Sultan; and the emergence of Dobhashi to write Muslim epics in Bengali literature.

The Bengal Sultanate was a melting pot of Muslim political, mercantile and military elites. Muslims from other parts of the world migrated to Bengal for military, bureaucratic and household services.[56] Immigrants included Persians who were lawyers, teachers, clerics, and scholars;[57] Turks from upper India who were originally recruited in Central Asia; and Abyssinians who came via East Africa and arrived in the Bengali port of Chittagong.[56] A highly commercialized and monetized economy evolved.

The two most prominent dynasties of the Bengal Sultanate were the Ilyas Shahi and Hussain Shahi dynasties. The reign of Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah saw the opening of diplomatic relations with Ming China. Ghiyasuddin was also a friend of the Persian poet Hafez. The reign of the Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah saw the development of Bengali architecture. During the early 15th century, the Restoration of Min Saw Mon in Arakan was aided by the army of the Bengal Sultanate. As a result, Arakan became a tributary state of Bengal. Even though Arakan later became independent, Bengali Muslim influence in Arakan persisted for 300 years due to the settlement of Bengali bureaucrats, poets, military personnel, farmers, artisans and sailors. The kings of Arakan fashioned themselves after Bengali Sultans and adopted Muslim titles.[58][59] During the reign of Sultan Alauddin Hussain Shah, the Bengal Sultanate dispatched a naval flotilla and an army of 24,000 soldiers led by Shah Ismail Ghazi to conquer Assam.[60] Bengali forces penetrated deep into the Brahmaputra Valley. Hussain Shah's forces also conquered Jajnagar in Orissa.[61][62] In Tripura, Bengal helped Ratna Manikya I to assume the throne.[63][64][65] The Jaunpur Sultanate, Pratapgarh Kingdom and the island of Chandradwip also came under Bengali control.[66][67][68][69][70] By 1500, Gaur became the fifth-most populous city in the world with a population of 200,000.[71][72] The river port of Sonargaon was used as a base by the Sultans of Bengal during campaigns against Assam, Tripura and Arakan. The Sultans launched many naval raids from Sonargaon.[73] João de Barros described the sea port of Chittagong as "the most famous and wealthy city of the Kingdom of Bengal".[74] Maritime trade linked Bengal with China, Malacca, Sumatra, Brunei, Portuguese India, East Africa, Arabia, Persia, Mesopotamia, Yemen and the Maldives. Bengali ships were among the biggest vessels plying the Bay of Bengal, Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean. A royal vessel from Bengal accommodated three embassies from Bengal, Brunei and Sumatra while en route to China and was the only vessel capable of transporting three embassies.[75] Many wealthy Bengali shipowners and merchants lived in Malacca. The Sultans permitted the opening of the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong. The disintegration of the Bengal Sultanate began with the intervention of the Suri Empire. Babur began invading Bengal after creating the Mughal Empire. The Bengal Sultanate collapsed with the overthrow of the Karrani dynasty during the reign of Akbar. However, the Bhati region of eastern Bengal continued to be ruled by aristocrats of the former Bengal Sultanate led by Isa Khan. They formed an independent federation called the Twelve Bhuiyans, with their capital in Sonargaon. They defeated the Mughals in several naval battles. The Bhuiyans ultimately succumbed to the Mughals after Musa Khan was defeated.

The Mughal Empire controlled Bengal by the 17th century. During the reign of Emperor Akbar, the Bengali agrarian calendar was reformed to facilitate tax collection. The Mughals established Dhaka as a fort city and commercial metropolis, and it was the capital of Bengal Subah for 75 years.[76] In 1666, the Mughals expelled the Arakanese from Chittagong. Mughal Bengal attracted foreign traders for its muslin and silk goods, and the Armenians were a notable merchant community. A Portuguese settlement in Chittagong flourished in the southeast, and a Dutch settlement in Rajshahi existed in the north. Bengal accounted for 40% of overall Dutch imports from Asia; including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks.[77] The Bengal Subah, described as the Paradise of the Nations,[78] was the empire's wealthiest province, and a major global exporter,[77][79][80] a notable centre of worldwide industries such as muslin, cotton textiles, silk,[37] and shipbuilding.[81] Its citizens also enjoyed one of the world's most superior living standards.[82][83]

During the 18th century, the Nawabs of Bengal became the region's de facto rulers. The ruler's title is popularly known as the Nawab of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, given that the Bengali Nawab's realm encompassed much of the eastern subcontinent. The Nawabs forged alliances with European colonial companies, making the region relatively prosperous early in the century. Bengal accounted for 50% of the gross domestic product of the empire. The Bengali economy relied on textile manufacturing, shipbuilding, saltpetre production, craftsmanship, and agricultural produce. Bengal was a major hub for international trade – silk and cotton textiles from Bengal were worn in Europe, Japan, Indonesia, and Central Asia.[84][37] Annual Bengali shipbuilding output was 223,250 tons, compared to an output of 23,061 tons in the nineteen colonies of North America. Bengali shipbuilding proved to be more advanced than European shipbuilding before the Industrial Revolution. The flush deck of Bengali rice ships was later replicated in European shipbuilding to replace the stepped deck design for ship hulls.[83][85][86][14][87][88]

Eastern Bengal was a thriving melting pot with strong trade and cultural networks. It was a relatively prosperous part of the subcontinent and the center of the Muslim population in the eastern subcontinent.[85][89] The Muslims of eastern Bengal included people of diverse origins from different parts of the world.[90]

The Bengali Muslim population was a product of conversion and religious evolution,[37] and their pre-Islamic beliefs included elements of Buddhism and Hinduism. The construction of mosques, Islamic academies (madrasas) and Sufi monasteries (khanqahs) facilitated conversion, and Islamic cosmology played a significant role in developing Bengali Muslim society. Scholars have theorised that Bengalis were attracted to Islam by its egalitarian social order, which contrasted with the Hindu caste system.[91] By the 15th century, Muslim poets were widely writing in the Bengali language. Syncretic cults, such as the Baul movement, emerged on the fringes of Bengali Muslim society. The Persianate culture was significant in Bengal, where cities like Sonargaon became the easternmost centres of Persian influence.[92][93]

In 1756, nawab Siraj ud-Daulah sought to rein in the rising power of the British East India Company by revoking their free trade rights and demanding the dismantling of their fortification in Calcutta. A military conflict ensued which culminated in the Battle of Plassey on 22 June 1757.[94] Robert Clive exploited rivalries within the nawab's family, bribing Mir Jafar, the nawab's uncle and commander in chief, to ensure Siraj-ud-Daula's defeat.[95][96] Clive rewarded Mir Jafar by making him nawab in place of Siraj-ud-Daula, but henceforth the position was a figurehead appointed and controlled by the company.[97] After Plassey, the Mughal emperor ruled Bengal in name only.[98] Effective power rested with the company. Historians often describe the battle as "the beginning of British colonial rule in South Asia".[99] Historian Willem van Schendel describes it as "The beginning of empire" for Britain.[100]

The Company replaced Mir Jafar with his son-in-law, Mir Kasim, in 1760. Mir Kasim challenged British control by allying with Mughal emperor Shah Alam II and the Nawab of Awadh, Shuja ud-Daulah, but the company decisively defeated the three at the Battle of Buxar on 23 October 1764.[96][98] The resulting treaty made the Mughal emperor a puppet of the British and gave the company the right to collect taxes (diwani) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, giving them de facto control of the region.[98][100] The Company used Bengal's tax revenue to conquer the rest of India.[100] By 1857, the Company controlled over 60% of the subcontinent directly, and exercised indirect rule over the remainder.[101]

Colonial period

Two decades after Vasco Da Gama's landing in Calicut, the Bengal Sultanate permitted the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong to be established in 1528. It became the first European colonial enclave in Bengal. The Bengal Sultanate lost control of Chittagong in 1531 after Arakan declared independence and the established Kingdom of Mrauk U.

Portuguese ships from Goa and Malacca began frequenting the port city in the 16th century. The cartaz system was introduced and required all ships in the area to purchase naval trading licenses from the Portuguese settlement. Slave trade and piracy flourished. The nearby island of Sandwip was conquered in 1602. In 1615, the Portuguese Navy defeated a joint Dutch East India Company and Arakanese fleet near the coast of Chittagong.

The Bengal Sultan after 1534 allowed the Portuguese to create several settlements at Chitagoong, Satgaon,[102] Hughli, Bandel, and Dhaka. In 1535, the Portuguese allied with the Bengal sultan and held the Teliagarhi pass 280 kilometres (170 mi) from Patna helping to avoid the invasion by the Mughals. By then several of the products came from Patna and the Portuguese send in traders, establishing a factory there since 1580.[103]

By the time the Portuguese assured military help against Sher Shah, the Mughals already had started to conquer the Sultanate of Ghiyasuddin Mahmud.[104]

Bengal was the wealthiest region in the Indian subcontinent, and its proto-industrial economy showed signs of driving an Industrial revolution.[105]

The region has been described as the "Paradise of Nations",[106] and its inhabitants's living standards and real wages were among the highest in the world.[107] It alone accounted for 40% of Dutch imports outside the European continent.[77][85] The eastern part of Bengal was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding,[108] and it was a major exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpeter, and agricultural and industrial produce in the world.[85] In 1666, the Mughal government of Bengal led by viceroy Shaista Khan moved to retake Chittagong from Portuguese and Arakanese control. The Anglo-Mughal War was witnessed in 1686.[109][110]

After the 1757 Battle of Plassey, Bengal was the first region of the Indian subcontinent conquered by the British East India Company. The company formed the Presidency of Fort William, which administered the region until 1858. A notable aspect of Company rule was the Permanent Settlement, which established the feudal zamindari system; in addition, Company policies led to the deindustrialisation of Bengal's textile industry.[111] The capital amassed by the East India Company in Bengal was invested in the emerging Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, in industries such as textile manufacturing.[112][113] Economic mismanagement, alongside drought and a smallpox epidemic, directly led to the Great Bengal famine of 1770, which is estimated to have caused the deaths of between 1 million and 10 million people.[114][115][116][117] Several rebellions broke out during the early 19th century (including one led by Titumir), as Company rule had displaced the Muslim ruling class from power. A conservative Islamic cleric, Haji Shariatullah, sought to overthrow the British by propagating Islamic revivalism.[118] Several towns in Bangladesh participated in the Indian Rebellion of 1857[119] and pledged allegiance to the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, who was later exiled to neighbouring Burma.

The challenge posed to company rule by the failed Indian Mutiny led to the creation of the British Indian Empire as a crown colony. The British established several schools, colleges, and a university in Bangladesh. Syed Ahmed Khan and Ram Mohan Roy promoted modern and liberal education in the subcontinent, inspiring the Aligarh movement[120] and the Bengal Renaissance.[121] During the late 19th century, novelists, social reformers and feminists emerged from Muslim Bengali society. Electricity and municipal water systems were introduced in the 1890s; cinemas opened in many towns during the early 20th century. East Bengal's plantation economy was important to the British Empire, particularly its jute and tea. The British established tax-free river ports, such as the Port of Narayanganj, and large seaports like the Port of Chittagong.

Bengal had the highest gross domestic product in British India.[122] Bengal was one of the first regions in Asia to have a railway. The first railway in what is now Bangladesh began operating in 1862.[123] In comparison, Japan saw its first railway in 1872. The main railway companies in the region were the Eastern Bengal Railway and Assam Bengal Railway. Railways competed with waterborne transport to become one of the main mediums of transport.[124]

Supported by the Muslim aristocracy, the British government created the province of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905; the new province received increased investment in education, transport, and industry.[125] However, the first partition of Bengal created an uproar in Calcutta and the Indian National Congress. In response to growing Hindu nationalism, the All India Muslim League was formed in Dhaka during the 1906 All India Muhammadan Educational Conference. The British government reorganised the provinces in 1912, reuniting East and West Bengal and making Assam a second province.

The Raj was slow to allow self-rule in the colonial subcontinent. It established the Bengal Legislative Council in 1862, and the council's native Bengali representation increased during the early 20th century. The Bengal Provincial Muslim League was formed in 1913 to advocate civil rights for Bengali Muslims within a constitutional framework. During the 1920s, the league was divided into factions supporting the Khilafat movement and favouring co-operation with the British to achieve self-rule. Segments of the Bengali elite supported Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's secularist forces.[126] In 1929, the All Bengal Tenants Association was formed in the Bengal Legislative Council to counter the influence of the Hindu landed gentry, and the Indian Independence and Pakistan Movements strengthened during the early 20th century. After the Morley-Minto Reforms and the diarchy era in the legislatures of British India, the British government promised limited provincial autonomy in 1935. The Bengal Legislative Assembly, British India's largest legislature, was established in 1937.

Although it won most seats in 1937, the Bengal Congress boycotted the legislature. A. K. Fazlul Huq of the Krishak Praja Party was elected as the first Prime Minister of Bengal. In 1940 Huq supported the Lahore Resolution, which envisaged independent states in the subcontinent's northwestern and eastern Muslim-majority regions. The first Huq ministry, a coalition with the Bengal Provincial Muslim League, lasted until 1941; it was followed by a Huq coalition with the Hindu Mahasabha which lasted until 1943. Huq was succeeded by Khawaja Nazimuddin, who grappled with the effects of the Burma Campaign, the Bengal famine of 1943, which killed up to 3 million people,[127] and the Quit India movement. In 1946, the Bengal Provincial Muslim League won the provincial election, taking 113 of the 250-seat assembly (the largest Muslim League mandate in British India). H. S. Suhrawardy, who made a final futile effort for a United Bengal in 1946, was the last premier of Bengal.

Partition of Bengal (1947)

On 3 June 1947, the Mountbatten Plan outlined the partition of British India. On 20 June, the Bengal Legislative Assembly met to decide on the partition of Bengal. At the preliminary joint meeting, it was decided (120 votes to 90) that if the province remained united, it should join the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. At a separate meeting of legislators from West Bengal, it was decided (58 votes to 21) that the province should be partitioned and West Bengal should join the Constituent Assembly of India. At another meeting of legislators from East Bengal, it was decided (106 votes to 35) that the province should not be partitioned and (107 votes to 34) that East Bengal should join the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan if Bengal was partitioned.[128] On 6 July, the Sylhet region of Assam voted in a referendum to join East Bengal. Cyril Radcliffe was tasked with drawing the borders of Pakistan and India, and the Radcliffe Line established the borders of present-day Bangladesh. The Radcliffe Line awarded two-thirds of Bengal as the eastern wing of Pakistan, although the medieval and early modern Bengali capitals of Gaur, Pandua and Murshidabad fell on the Indian side close to the border with Pakistan.

Union with Pakistan

.svg.png.webp)

The Dominion of Pakistan was created on 14 August 1947. East Bengal, with Dhaka as its capital, was the most populous province of the 1947 Pakistani federation (led by Governor General Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who promised freedom of religion and secular democracy in the new state).[129][130]

Khawaja Nazimuddin was East Bengal's first chief minister with Frederick Chalmers Bourne its governor. The All Pakistan Awami Muslim League was formed in 1949. In 1950, the East Bengal Legislative Assembly enacted land reform, abolishing the Permanent Settlement and the zamindari system.[131] The 1952 Bengali Language Movement was the first sign of friction between the country's geographically separated wings. The Awami Muslim League was renamed the more-secular Awami League in 1953.[132] The first constituent assembly was dissolved in 1954; this was challenged by its East Bengali speaker, Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan. The United Front coalition swept aside the Muslim League in a landslide victory in the 1954 East Bengali legislative election. The following year, East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan as part of the One Unit program, and the province became a vital part of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization.

Pakistan adopted a new constitution in 1956. Three Bengalis were its Prime Minister until 1957: Nazimuddin, Mohammad Ali of Bogra and Suhrawardy. None of the three completed their terms, and resigned from office. The Pakistan Army imposed military rule in 1958, and Ayub Khan was the country's strongman for 11 years. Political repression increased after the coup. Khan introduced a new constitution in 1962, replacing Pakistan's parliamentary system with a presidential and gubernatorial system (based on electoral college selection) known as Basic Democracy. In 1962 Dhaka became the seat of the National Assembly of Pakistan, a move seen as appeasing increased Bengali nationalism.[133] The Pakistani government built the controversial Kaptai Dam, displacing the Chakma people from their indigenous homeland in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.[134] During the 1965 presidential election, Fatima Jinnah lost to Ayub Khan despite support from the Combined Opposition alliance (which included the Awami League).[135] The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 blocked cross-border transport links with neighbouring India in what is described as a second partition.[136] In 1966, Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman announced a six-point movement for a federal parliamentary democracy.

According to senior World Bank officials, the Pakistani government practised extensive economic discrimination against East Pakistan: greater government spending on West Pakistan, financial transfers from East to West Pakistan, the use of East Pakistan's foreign-exchange surpluses to finance West Pakistani imports, and refusal by the central government to release funds allocated to East Pakistan because the previous spending had been under budget;[137] though East Pakistan generated 70 percent of Pakistan's export revenue with its jute and tea.[138] Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested for treason in the Agartala Conspiracy Case and was released during the 1969 uprising in East Pakistan which resulted in Ayub Khan's resignation. General Yahya Khan assumed power, reintroducing martial law.

Ethnic and linguistic discrimination was common in Pakistan's civil and military services, in which Bengalis were under-represented. Fifteen percent of Pakistani central-government offices were occupied by East Pakistanis, who formed 10 percent of the military.[139] Cultural discrimination also prevailed, making East Pakistan forge a distinct political identity.[140] Authorities banned Bengali literature and music in state media, including the works of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore.[141] A cyclone devastated the coast of East Pakistan in 1970, killing an estimated 500,000 people,[142] and the central government was criticised for its poor response.[143] After the December 1970 elections, calls for the independence of East Bengal became louder; the Bengali-nationalist Awami League won 167 of 169 East Pakistani seats in the National Assembly. The League claimed the right to form a government and develop a new constitution but was strongly opposed by the Pakistani military and the Pakistan Peoples Party (led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto).

War of Independence

The Bengali population was angered when Prime Minister-elect Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was prevented from taking the office.[144] Civil disobedience erupted across East Pakistan,[145] with calls for independence. Mujib addressed a pro-independence rally of nearly 2 million people in Dacca (as Dhaka used to be spelled in English) on 7 March 1971, where he said, "This time the struggle is for our freedom. This time the struggle is for our independence."[146] The flag of Bangladesh was raised for the first time on 23 March, Pakistan's Republic Day.[147] Later, on 25 March late evening, the Pakistani military junta led by Yahya Khan launched a sustained military assault on East Pakistan under the code name of Operation Searchlight.[148][149] The Pakistan Army arrested Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and flew him to Karachi.[150][151][152] However, before his arrest Mujib proclaimed the Independence of Bangladesh at midnight on 26 March which led the Bangladesh Liberation War to break out within hours.[153][154] The Pakistan Army and its local supporters continued to massacre Bengalis, in particular students, intellectuals, political figures, and Hindus in the 1971 Bangladesh genocide. The Mukti Bahini, a guerrilla resistance force, also violated human rights during the conflict.[155] During the war, an estimated 0.3 to 3.0 million people were killed and several million people took shelter in neighbouring India.[156]

Global public opinion turned against Pakistan as news of the atrocities spread;[157] the Bangladesh movement was supported by prominent political and cultural figures in the West, including Ted Kennedy, George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Victoria Ocampo and André Malraux.[158][159][160] The Concert for Bangladesh was held at Madison Square Garden in New York City to raise funds for Bangladeshi refugees. The first major benefit concert in history, it was organised by Harrison and Indian Bengali sitarist Ravi Shankar.[161]

During the Bangladesh Liberation War, Bengali nationalists declared independence and formed the Mukti Bahini (the Bangladeshi National Liberation Army). The Provisional Government of Bangladesh was established on 17 April 1971, converting the 469 elected members of the Pakistani national assembly and East Pakistani provincial assembly into the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh. The provisional government issued a proclamation that became the country's interim constitution and declared "equality, human dignity, and social justice" as its fundamental principles. Due to Mujib's detention, Syed Nazrul Islam took over the role of Acting President, while Tajuddin Ahmad was named Bangladesh's first Prime Minister. The Mukti Bahini and other Bengali guerrilla forces formed the Bangladesh Forces, which became the military wing of the provisional government. Led by General M. A. G. Osmani and eleven sector commanders, the forces held the countryside during the war. They conducted wide-ranging guerrilla operations against Pakistani forces. As a result, almost the entire country except for the capital Dacca was liberated by Bangladesh Forces by late November.

This led the Pakistan Army to attack neighbouring India's western front on 2 December 1971. India retaliated in both the western and eastern fronts. With a joint ground advance by Bangladeshi and Indian forces, coupled with air strikes by both India and the small Bangladeshi air contingent, the capital Dacca was liberated from Pakistani occupation in mid-December. During the last phase of the war, both the Soviet Union and the United States dispatched naval forces to the Bay of Bengal in a Cold War standoff. The nine month long war ended with the surrender of Pakistani armed forces to the Bangladesh-India Allied Forces on 16 December 1971.[162][163] Under international pressure, Pakistan released Rahman from imprisonment on 8 January 1972 and he was flown by the British Royal Air Force to a million-strong homecoming in Dacca.[164][165] Remaining Indian troops were withdrawn by 12 March 1972, three months after the war ended.[166]

The cause of Bangladeshi self-determination was recognised around the world. By August 1972, the new state was recognised by 86 countries.[157] Pakistan recognised Bangladesh in 1974 after pressure from most of the Muslim countries.[167]

First parliamentary era

The constituent assembly adopted the constitution of Bangladesh on 4 November 1972, establishing a secular, multiparty parliamentary democracy. The new constitution included references to socialism, and Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman nationalised major industries in 1972.[168] A major reconstruction and rehabilitation program was launched. The Awami League won the country's first general election in 1973, securing a large majority in the "Jatiyo Sangshad", the national parliament. Bangladesh joined the Commonwealth of Nations, the UN, the OIC and the Non-Aligned Movement, and Rahman strengthened ties with India. Amid growing agitation by the opposition National Awami Party and Jashod, he became increasingly authoritarian. Rahman amended the constitution, giving himself more emergency powers (including the suspension of fundamental rights). The Bangladesh famine of 1974 also worsened the political situation.[169]

Presidential era (1975–1991)

_en_echtgenot%252C_Bestanddeelnr_253-8087.jpg.webp)

In January 1975, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman introduced one-party socialist rule under BAKSAL. Rahman banned all newspapers except four state-owned publications and amended the constitution to increase his power. He was assassinated during a coup on 15 August 1975. Martial law was declared, and the presidency passed to the usurper Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad for four months. Ahmad is widely regarded as a traitor by Bangladeshis.[170] Tajuddin Ahmad, the nation's first prime minister, and four other independence leaders were assassinated on 4 November 1975. Chief Justice Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem was installed as president by the military on 6 November 1975. Bangladesh was governed by a military junta led by the Chief Martial Law Administrator for three years. In 1977, the army chief Ziaur Rahman became president. Rahman reinstated multiparty politics, privatised industries and newspapers, established BEPZA and held the country's second general election in 1979. A semi-presidential system evolved, with the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) governing until 1982. Rahman was assassinated in 1981 and was succeeded by Vice-president Abdus Sattar. Sattar received 65.5 per cent of the vote in the 1981 presidential election.[171]

After a year in office, Sattar was overthrown in the 1982 Bangladesh coup d'état. Chief Justice A. F. M. Ahsanuddin Chowdhury was installed as president, but army chief Hussain Muhammad Ershad became the country's de facto leader and assumed the presidency in 1983. Ershad lifted martial law in 1986. He governed with four successive prime ministers (Ataur Rahman Khan, Mizanur Rahman Chowdhury, Moudud Ahmed and Kazi Zafar Ahmed) and a parliament dominated by his Jatiyo Party. General elections were held in 1986 and 1988, although the opposition BNP and Awami League boycotted the latter. Ershad pursued administrative decentralisation, dividing the country into 64 districts, and pushed Parliament to make Islam the state religion in 1988.[172] A 1990 mass uprising forced him to resign, and Chief Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed led the country's first caretaker government as part of the transition to parliamentary rule.[171]

Parliamentary era (1991–present)

After the 1991 general election, the twelfth amendment to the constitution restored the parliamentary republic and Begum Khaleda Zia became Bangladesh's first female prime minister. Zia, a former first lady, led a BNP government from 1990 to 1996. In 1991, her finance minister, Saifur Rahman, began a major program to liberalise the Bangladeshi economy.[169]

In February 1996, a general election was held, which was boycotted by all opposition parties giving a 300 (of 300) seat victory for BNP. This election was deemed illegitimate, so a system of a caretaker government was introduced to oversee the transfer of power and a new election was held in June 1996, overseen by Justice Muhammad Habibur Rahman, the first Chief Adviser of Bangladesh. The Awami League won the seventh general election, marking its leader Sheikh Hasina's first term as Prime Minister. Hasina's first term was highlighted by the Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord and a Ganges water-sharing treaty with India. The second caretaker government, led by Chief Adviser Justice Latifur Rahman, oversaw the 2001 Bangladeshi general election which returned Begum Zia and the BNP to power.

The second Zia administration saw improved economic growth, but political turmoil gripped the country between 2004 and 2006. A radical Islamist militant group, the JMB, carried out a series of terror attacks. The evidence of staging these attacks by these extremist groups have been found in the investigation. Hundreds of suspected members were detained in numerous security operations in 2006, including the two chiefs of the JMB, Shaykh Abdur Rahman and Bangla Bhai, who was executed with other top leaders in March 2007, bringing the militant group to an end.[173]

In 2006, at the end of the term of the BNP administration, there was widespread political unrest related to the handover of power to a caretaker government. As such, the Bangladeshi military urged President Iajuddin Ahmed to impose a state of emergency and a caretaker government, led by technocrat Fakhruddin Ahmed, was installed.[169] Emergency rule lasted for two years, during which time investigations into members of both Awami League and BNP were conducted, including their leaders Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia.[174][175] In 2008, the ninth general election saw a return to power for Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League led Grand Alliance in a landslide victory. In 2010, the Supreme Court ruled martial law illegal and affirmed secular principles in the constitution. The following year, the Awami League abolished the caretaker government system.

Citing the lack of caretaker government, the 2014 general election was boycotted by the BNP and other opposition parties, giving the Awami League a decisive victory. The election was controversial with reports of violence and an alleged crackdown on the opposition in the run-up to the election, and 153 seats (of 300) went uncontested in the election. Despite the controversy, Hasina went on to form a government that saw her return for a third term as Prime Minister. Due to strong domestic demand, Bangladesh emerged as one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.[176] However, human rights abuses increased under the Hasina administration, particularly enforced disappearances. Between 2016 and 2017, an estimated 1 million Rohingya refugees took shelter in southeastern Bangladesh amid a military crackdown in neighbouring Rakhine State, Myanmar.

In 2018, the country saw major movements for government quota reforms and road-safety. The 2018 Bangladeshi general election was marred by allegations of widespread vote rigging.[177] The Awami League won 259 out of 300 seats and the main opposition alliance Jatiya Oikya Front secured only 8 seats, with Sheikh Hasina becoming the longest-serving prime minister in Bangladeshi history.[178] Pro-democracy leader Dr. Kamal Hossain called for an annulment of the election result and for a new election to be held in a free and fair manner.[179] The election was also observed by European Union observers.[180]

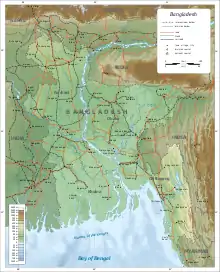

Geography

Bangladesh is a small, lush country in South Asia, located on the Bay of Bengal. It is surrounded almost entirely by neighbouring India—and shares a small border with Myanmar to its southeast, though it lies very close to Nepal, Bhutan, and China. The country is divided into three regions. Most of the country is dominated by the fertile Ganges Delta, the largest river delta in the world.[181] The northwest and central parts of the country are formed by the Madhupur and the Barind plateaus. The northeast and southeast are home to evergreen hill ranges.

The Ganges delta is formed by the confluence of the Ganges (local name Padma or Pôdda), Brahmaputra (Jamuna or Jomuna), and Meghna rivers and their respective tributaries. The Ganges unites with the Jamuna (main channel of the Brahmaputra) and later joins the Meghna, finally flowing into the Bay of Bengal. Bangladesh is called the "Land of Rivers";[182] as it is home to over 57 trans-boundary rivers. However, this resolves water issues politically complicated, in most cases, as the country is a lower riparian state to India.[183]

Bangladesh is predominantly rich fertile flat land. Most of it is less than 12 m (39 ft) above sea level, and it is estimated that about 10% of its land would be flooded if the sea level were to rise by 1 m (3.3 ft).[184] 17% of the country is covered by forests and 12% is covered by hill systems. The country's haor wetlands are of significance to global environmental science. The highest point in Bangladesh is the Saka Haphong, located near the border with Myanmar, with an elevation of 1,064 m (3,491 ft).[185] Previously, either Keokradong or Tazing Dong were considered the highest.

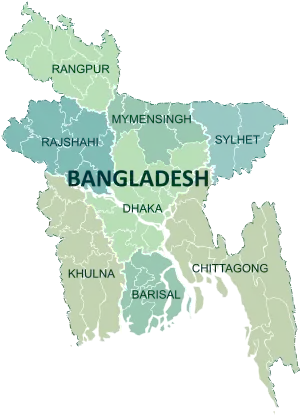

Administrative geography

Bangladesh is divided into eight administrative divisions,[186][185][187] each named after their respective divisional headquarters: Barisal (officially Barishal[188]), Chittagong (officially Chattogram[188]), Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Rangpur, and Sylhet.

Divisions are subdivided into districts (zila). There are 64 districts in Bangladesh, each further subdivided into upazila (subdistricts) or thana. The area within each police station, except for those in metropolitan areas, is divided into several unions, with each union consisting of multiple villages. In the metropolitan areas, police stations are divided into wards, further divided into mahallas.

There are no elected officials at the divisional or district levels, and the administration is composed only of government officials. Direct elections are held in each union (or ward) for a chairperson and a number of members. In 1997, a parliamentary act was passed to reserve three seats (out of 12) in every union for female candidates.[189]

| Division | Capital | Established | Area (km2) [190] |

2021 Population (projected)[191] |

Density 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barisal Division | Barisal | 1 January 1993 | 13,225 | 9,713,000 | 734 |

| Chittagong Division | Chittagong | 1 January 1829 | 33,909 | 34,747,000 | 1,025 |

| Dhaka Division | Dhaka | 1 January 1829 | 20,594 | 42,607,000 | 2,069 |

| Khulna Division | Khulna | 1 October 1960 | 22,284 | 18,217,000 | 817 |

| Mymensingh Division | Mymensingh | 14 September 2015 | 10,584 | 13,457,000 | 1,271 |

| Rajshahi Division | Rajshahi | 1 January 1829 | 18,153 | 21,607,000 | 1,190 |

| Rangpur Division | Rangpur | 25 January 2010 | 16,185 | 18,868,000 | 1,166 |

| Sylhet Division | Sylhet | 1 August 1995 | 12,635 | 12,463,000 | 986 |

Climate

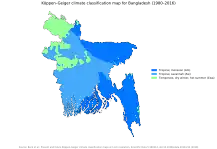

Straddling the Tropic of Cancer, Bangladesh's climate is tropical, with a mild winter from October to March and a hot, humid summer from March to June. The country has never recorded an air temperature below 0 °C (32 °F), with a record low of 1.1 °C (34.0 °F) in the northwest city of Dinajpur on 3 February 1905.[193] A warm and humid monsoon season lasts from June to October and supplies most of the country's rainfall. Natural calamities, such as floods, tropical cyclones, tornadoes, and tidal bores occur almost every year,[194] combined with the effects of deforestation, soil degradation and erosion. The cyclones of 1970 and 1991 were particularly devastating, the latter killing approximately 140,000 people.[195]

In September 1998, Bangladesh saw the most severe flooding in modern history, after which two-thirds of the country went underwater, along with a death toll of 1,000.[196] As a result of various international and national level initiatives in disaster risk reduction, human toll and economic damage from floods and cyclones have come down over the years.[197] The 2007 South Asian floods ravaged areas across the country, leaving five million people displaced, had a death toll around 500.[198]

Bangladesh is recognised to be one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change.[199][200] Over the course of a century, 508 cyclones have affected the Bay of Bengal region, 17 percent of which are believed to have caused landfall in Bangladesh.[201] Natural hazards that come from increased rainfall, rising sea levels, and tropical cyclones are expected to increase as the climate changes, each seriously affecting agriculture, water and food security, human health, and shelter.[202] It is estimated that by 2050, a 3 feet rise in sea levels will inundate some 20 percent of the land and displace more than 30 million people.[203] To address the sea level rise threat in Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 has been launched.[204][205]

Biodiversity

Bangladesh is located in the Indomalayan realm, and lies within four terrestrial ecoregions: Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests, Mizoram–Manipur–Kachin rain forests, Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests, and Sundarbans mangroves.[206] Its ecology includes a long sea coastline, numerous rivers and tributaries, lakes, wetlands, evergreen forests, semi evergreen forests, hill forests, moist deciduous forests, freshwater swamp forests and flat land with tall grass. The Bangladesh Plain is famous for its fertile alluvial soil which supports extensive cultivation. The country is dominated by lush vegetation, with villages often buried in groves of mango, jackfruit, bamboo, betel nut, coconut and date palm.[207] The country has up to 6000 species of plant life, including 5000 flowering plants.[208] Water bodies and wetland systems provide a habitat for many aquatic plants. Water lilies and lotuses grow vividly during the monsoon season. The country has 50 wildlife sanctuaries.

Bangladesh is home to much of the Sundarbans, the world's largest mangrove forest, covering an area of 6,000 km2 in the southwest littoral region. It is divided into three protected sanctuaries–the South, East and West zones. The forest is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The northeastern Sylhet region is home to haor wetlands, a unique ecosystem. It also includes tropical and subtropical coniferous forests, a freshwater swamp forest, and mixed deciduous forests. The southeastern Chittagong region covers evergreen and semi-evergreen hilly jungles. Central Bangladesh includes the plainland Sal forest running along with the districts of Gazipur, Tangail and Mymensingh. St. Martin's Island is the only coral reef in the country.

Bangladesh has an abundance of wildlife in its forests, marshes, woodlands and hills.[207] The vast majority of animals dwell within a habitat of 150,000 km2 .[209] The Bengal tiger, clouded leopard, saltwater crocodile, black panther and fishing cat are among the chief predators in the Sundarbans.[210] Northern and eastern Bangladesh is home to the Asian elephant, hoolock gibbon, Asian black bear and oriental pied hornbill.[211] The Chital deer are widely seen in southwestern woodlands. Other animals include the black giant squirrel, capped langur, Bengal fox, sambar deer, jungle cat, king cobra, wild boar, mongooses, pangolins, pythons and water monitors. Bangladesh has one of the largest populations of Irrawaddy dolphins and Ganges dolphins. A 2009 census found 6,000 Irrawaddy dolphins inhabiting the littoral rivers of Bangladesh.[212] The country has numerous species of amphibians (53), reptiles (139), marine reptiles (19) and marine mammals (5). It also has 628 species of birds.[213]

Several animals became extinct in Bangladesh during the last century, including the one-horned and two-horned rhinoceros and common peafowl. The human population is concentrated in urban areas, limiting deforestation to a certain extent. Rapid urban growth has threatened natural habitats. Although many areas are protected under law, some Bangladeshi wildlife is threatened by this growth. The Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act was enacted in 1995. The government has designated several regions as Ecologically Critical Areas, including wetlands, forests, and rivers. The Sundarbans tiger project and the Bangladesh Bear Project are among the key initiatives to strengthen conservation.[211] It ratified the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 3 May 1994.[214] As of 2014, the country was set to revise its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.[214]

Politics and government

Bangladesh is a de jure representative democracy under its constitution, with a Westminster-style unitary parliamentary republic that has universal suffrage. The head of government is the Prime Minister, who is invited to form a government every five years. The President invites the leader of the largest party in parliament to become Prime Minister of the world's fifth-largest democracy.[215] Bangladesh experienced a two party system between 1990 and 2014, when the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) alternated in power. During this period, elections were managed by a neutral caretaker government. But the caretaker government was abolished by the Awami League government in 2011.

One of the key aspects of Bangladeshi politics is the "spirit of the liberation war", which refers to the ideals of the liberation movement during the Bangladesh Liberation War.[216] The Proclamation of Independence enunciated the values of "equality, human dignity and social justice". In 1972, the constitution included a bill of rights and declared "nationalism, socialism, democracy and secularity" as the principles of government policy. Socialism was later de-emphasised and neglected by successive governments. Bangladesh has a market-based economy. To many Bangladeshis, especially in the younger generation, the spirit of the liberation war is a vision for a society based on civil liberties, human rights, the rule of law and good governance.[217]

- Legislative: The Jatiya Sangshad (National Parliament) is the unicameral parliament. It has 350 Members of Parliament (MPs), including 300 MPs elected on the first past the post system and 50 MPs appointed to reserved seats for women's empowerment. Article 70 of the Constitution of Bangladesh forbids MPs from voting against their party. However, several laws proposed independently by MPs have been transformed into legislation, including the anti-torture law.[218] The parliament is presided over by the Speaker of the Jatiya Sangsad, who is second in line to the president as per the constitution. There is also a Deputy Speaker. When a president is incapable of performing duties (i.e. due to illness), the Speaker steps in as Acting President and the Deputy Speaker becomes Acting Speaker. A recurring proposal suggests that the Deputy Speaker should be an opposition member.[219]

- Executive: The Government of Bangladesh is overseen by a cabinet headed by the Prime Minister of Bangladesh. The tenure of a parliamentary government is five years. The Bangladesh Civil Service assists the cabinet in running the government. Recruitment for the civil service is based on a public examination. In theory, the civil service should be a meritocracy. But a disputed quota system coupled with politicisation and preference for seniority have allegedly affected the civil service's meritocracy.[220] The President of Bangladesh is the ceremonial head of state[221] whose powers include signing bills passed by parliament into law. The President is elected by the parliament and has a five-year term. Under the constitution, the president acts on the prime minister's advice. The President is the Supreme Commander of the Bangladesh Armed Forces and the chancellor of all universities.

- Judiciary: The Supreme Court of Bangladesh is the highest court of the land, followed by the High Court and Appellate Divisions. The head of the judiciary is the Chief Justice of Bangladesh, who sits on the Supreme Court. The courts have wide latitude in judicial review, and judicial precedent is supported by Article 111 of the constitution. The judiciary includes district and metropolitan courts divided into civil and criminal courts. Due to a shortage of judges, the judiciary has a large backlog. The Bangladesh Judicial Service Commission is responsible for judicial appointments, salaries, and discipline.

Military

.jpg.webp)

The Bangladesh Armed Forces have inherited the institutional framework of the British military and the British Indian Army.[222] It was formed in 1971 from the military regiments of East Pakistan. In 2022, the active personnel strength of the Bangladesh Army was around 250,000,[223] excluding the Air Force and the Navy (24,000).[224] In addition to traditional defence roles, the military has supported civil authorities in disaster relief and provided internal security during periods of political unrest. For many years, Bangladesh has been the world's largest contributor to UN peacekeeping forces. The military budget of Bangladesh accounts for 1.3% of GDP, amounting to US$4.3 billion in 2021.[225][226]

The Bangladesh Navy, one of the largest in the Bay of Bengal, includes a fleet of frigates, submarines, corvettes and other vessels. The Bangladesh Air Force has a small fleet of multi-role combat aircraft, including the MiG-29 and Chengdu-F7. Most of Bangladesh's military equipment comes from China.[227] In recent years, Bangladesh and India have increased joint military exercises, high level visits of military leaders, counter-terrorism cooperation and intelligence sharing. Bangladesh is vital to ensuring stability and security in northeast India.[228][229]

Bangladesh's strategic importance in the eastern subcontinent hinges on its proximity to China, its frontier with Burma, the separation of mainland and northeast India, and its maritime territory in the Bay of Bengal.[230] In 2002, Bangladesh and China signed a Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA) which the governments of both countries said will "institutionalize the existing accords in defence sector and also to rationalize the existing piecemeal agreements to enhance cooperation in training, maintenance and in some areas of production".[231] The United States has pursued negotiations with Bangladesh on a Status of Forces Agreement, an Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement and a General Security of Military Information Agreement.[232][233][234] In 2019, Bangladesh ratified the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[235]

Foreign relations

.png.webp)

Bangladesh is considered a middle power in global politics.[236] It plays an important role in the geopolitical affairs of the Indo-Pacific,[237] due to its strategic location between South and Southeast Asia.[238] Bangladesh joined the Commonwealth of Nations in 1972 and the United Nations in 1974.[239][240] It relies on multilateral diplomacy on issues like climate change, nuclear nonproliferation, trade policy and non-traditional security issues.[241] At the WTO, Bangladesh has used the dispute resolution mechanism to settle trade disputes with India and other countries.[242] Bangladesh pioneered the creation of SAARC, which has been the preeminent forum for regional diplomacy among the countries of the Indian subcontinent.[243] It joined the OIC, an intergovernmental organization of the Muslim world in 1974,[244] and is a founding member of the Developing 8 Countries.[245] In recent years, Bangladesh has focused on promoting regional trade and transport links with support from the World Bank.[246] Dhaka hosts the headquarters of BIMSTEC, an organization that brings together countries dependent on the Bay of Bengal.

Relations with neighboring Myanmar have been severely strained since 2016–2017, after over 700,000 Rohingya refugees illegally entered Bangladesh fleeing persecution, ethnic cleansing, genocide, and other atrocities in their native state.[247] The parliament, government, and civil society of Bangladesh have been at the forefront of international criticism against Myanmar for military operations against the Rohingya, and have demanded their right of return to Arakan.[248][249] In 2021, Bangladesh provided a US$200 million loan to Sri Lanka and a US$7.7 million donation to Sudan as economic assistance.[250][251][252]

Bangladesh shares an important bilateral and economic relationship with its largest neighbor India,[253] which is often strained by water politics of the Ganges and the Teesta,[254][255][256] and the border killings of Bangladeshi civilians.[257][258] Post-independent Bangladesh has continued to have a problematic relationship with Pakistan, mainly due to its denial of the 1971 Bangladesh genocide.[259] It maintains a warm relationship with China, which is its largest trading partner, and the largest arms supplier.[260] Japan is Bangladesh's largest economic aid provider, and the two maintain a strategic and economic partnership.[261] Political relations with Middle Eastern countries are robust.[262] Bangladesh receives 59% of its remittances from the Middle East,[263] despite poor working conditions affecting over 4 million Bangladeshi workers.[264] Bangladesh plays a major role in global climate diplomacy as a leader of the Climate Vulnerable Forum.[265]

Civil society

Since the colonial period, Bangladesh has had a prominent civil society. There are various special interest groups, including non-governmental organisations, human rights organisations, professional associations, chambers of commerce, employers' associations and trade unions.[266] The National Human Rights Commission of Bangladesh was set up in 2007. Notable human rights organisations and initiatives include the Centre for Law and Mediation, Odhikar, the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association, the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council and the War Crimes Fact Finding Committee. The world's largest international NGO BRAC is based in Bangladesh. There have been concerns regarding the shrinking space for independent civil society in recent years,[267][268] with commentators labelling the civil society movement dead under the authoritarianism of the Awami League.[269]

Human rights

Torture is banned by Article 35 (5) of the Constitution of Bangladesh.[270] Despite this constitutional ban, torture is rampantly used by Bangladesh's security forces. Bangladesh joined the Convention against Torture in 1998; but it enacted its first anti-torture law, the Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention) Act, in 2013. The first conviction under this law was announced in 2020.[271] Amnesty International Prisoners of Conscience from Bangladesh have included Saber Hossain Chowdhury and Shahidul Alam.[272][273] The Digital Security Act of 2018 has greatly reduced freedom of expression in Bangladesh, particularly on the internet. The Digital Security Act has been used to target critics of the government and bureaucracy. Newspaper editorials have been demanding the repeal of the Digital Security Act.[274][275][276][277]

On International Human Rights Day in December 2021, the United States Department of Treasury announced sanctions on commanders of the Rapid Action Battalion for extrajudicial killings, torture and other human rights abuses.[278] Freedom House has criticised the ruling party for human rights abuses, crackdown on opposition, mass media, and civil society through politicized enforcement.[279] Bangladesh is ranked "partly free" in Freedom House's Freedom in the World report,[280] but its press freedom has deteriorated from "free" to "not free" in recent years due to increasing pressure from the authoritarian government.[281] According to the British Economist Intelligence Unit, the country has a hybrid regime: the third of four rankings in its Democracy Index.[282] Bangladesh was ranked 96th among 163 countries in the 2022 Global Peace Index.[283] According to National Human Rights Commission, 70% of alleged human-rights violations are committed by law-enforcement agencies.[284]

LGBT rights are heavily suppressed by both government and society,[285] as homosexuality is outlawed by section 377 of the criminal code (a legacy of the colonial period), and is punishable by a maximum of life imprisonment.[286][287] However, Bangladesh recognises the third gender and accords limited rights for transgender people.[288] According to the 2016 Global Slavery Index, an estimated 1,531,300 people are enslaved in Bangladesh, or roughly 1% of the population.[289] A number of slaves in Bangladesh are forced to work in the fish and shrimp industries.[290][291][292]

Corruption

Like for many developing countries, institutional corruption is a serious concern for Bangladesh. Bangladesh was ranked 146th among 180 countries on Transparency International's 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index.[293] According to survey conducted by the Bangladesh chapter of TI, in 2015, bribes made up 3.7 percent of the national budget.[294] Land administration was the sector with the most bribery in 2015,[294] followed by education,[295] police[296] and water supply.[297] The Anti Corruption Commission was formed in 2004, and it was active during the 2006–08 Bangladeshi political crisis, indicting many leading politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen for graft.[298][299][300]

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

Bangladesh is the second largest economy in South Asia after India.[302][303] The country has outpaced India (of which it was a part until 1947) and Pakistan (of which it was a part until 1971) in terms of per capita income.[304][303] According to the World Bank, "When the newly independent country of Bangladesh was born on December 16, 1971, it was the second poorest country in the world—making the country's transformation over the next 50 years one of the great development stories. Since then, poverty has been cut in half at record speed. Enrollment in primary school is now nearly universal. Hundreds of thousands of women have entered the workforce. Steady progress has been made on maternal and child health. And the country is better buttressed against the destructive forces posed by climate change and natural disasters. Bangladesh’s success comprises many moving parts—from investing in human capital to establishing macroeconomic stability. Building on this success, the country is now setting the stage for further economic growth and job creation by ramping up investments in energy, inland connectivity, urban projects, and transport infrastructure, as well as prioritizing climate change adaptation and disaster preparedness on its path toward sustainable growth".[305]

Since 2009, Bangladesh has embarked on a series of megaprojects. The 6.15 km long Padma Bridge was built at a cost of US$3.86 billion.[306] The bridge was the first self-financed megaproject in the country's history.[307] Other megaprojects include the Dhaka Metro, Karnaphuli Tunnel, Dhaka Elevated Expressway and Chittagong Elevated Expressway; as well as the Bangladesh Delta Plan to mitigate the impact of climate change. Overseas remittances from expat Bangladeshis and export earnings from the Bangladesh textile industry have allowed the country to have the second largest foreign-exchange reserves in South Asia. The reserves have boosted the government's spending capacity in spite of tax revenues forming only 7.7% of government revenue.[308] A big chunk of investments have gone into the power sector. In 2009, Bangladesh was experiencing daily blackouts several times a day. In 2022, the country achieved 100% electrification.[309][310][311]

The private sector accounts for 80% of GDP in comparison to the dwindling role of state-owned companies.[312] Bangladesh's economy is dominated by family-owned conglomerates and small and medium-sized businesses. Some of the largest publicly-traded companies in Bangladesh include Beximco, BRAC Bank, BSRM, GPH Ispat, Grameenphone, Summit Group, and Square Pharmaceuticals.[313] Capital markets include the Dhaka Stock Exchange and the Chittagong Stock Exchange. Its telecommunications industry is one of the world's fastest growing, with 171.854 million cellphone subscribers in January 2021.[314] Over 80% of the export earnings are from the textile industry.[7] Other major industries include shipbuilding, pharmaceuticals, steel, electronics and leather goods.[315] Muhammad Aziz Khan became the first person from Bangladesh to be listed as a billionaire by Forbes.[316]

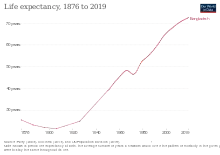

The poverty rate has gone down from 80% in 1971,[317] to 44.2% in 1991,[318] to 12.9% in 2021.[319] The literacy rate stood at 74.66% in 2022.[320] Bangladesh has a labor force of roughly 70 million,[321] which is the world's seventh-largest; with an unemployment rate of 5.2% as of 2021.[322] The government is setting up 100 special economic zones to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) and generate 10 million jobs.[323] The Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA) and the Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA) have been established to help investors in setting up factories; and to complement the longstanding Bangladesh Export Processing Zone Authority (BEPZA).

The Bangladeshi taka is the national currency. The service sector accounts for about 51.3% of total GDP and employs 39% of the workforce. The industrial sector accounts for 35.1% of GDP and employs 20.4% of the workforce. The agriculture sector makes up 13.6% of the economy but is the biggest employment sector, with 40.6% of the workforce.[308] In agriculture, the country is a major producer of rice, fish, tea, fruits, vegetables, flowers,[324] and jute. Lobsters and shrimps are some of Bangladesh's well known exports.[325]

Bangladesh is gradually transitioning to a green economy. Currently, it has the largest off-grid solar power program in the world, benefiting 20 million people.[326] An electric car called the Palki is being developed for production in the country.[327] The government has reduced tariffs for the purchase of electric cars.[328] Biogas is being used to produce organic fertilizer.[329]

Bangladesh continues to have huge untapped reserves of natural gas, particularly in its maritime territory in the Bay of Bengal.[330][331] The success ratio of finding gas wells in the country stands at 3:5:1, meaning one commercial deposit is found in every three explored zones.[332] The success ratio is well above the global average.[332] A lack of exploration and decreasing proven reserves have forced Bangladesh to import LNG from abroad, despite having substantially untapped gas reserves.[333][334][335] Gas shortages were further exasperated by the Russia-Ukraine War.[336]

The tourism industry is expanding, contributing some 3.02% of total GDP.[337] Bangladesh's international tourism receipts in 2019 amounted to $391 million.[338] The country has three UNESCO World Heritage Sites (the Mosque City, the Buddhist Vihara and the Sundarbans) and five tentative-list sites.[339] Activities for tourists include angling, water skiing, river cruising, hiking, rowing, yachting, and sea bathing.[340][341] The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) reported in 2019 that the travel and tourism industry in Bangladesh directly generated 1,180,500 jobs in 2018 or 1.9% of the country's total employment.[342] According to the same report, Bangladesh experiences around 125,000 international tourist arrivals per year.[342] Domestic spending generated 97.7 percent of direct travel and tourism gross domestic product (GDP) in 2012.[343]

Electricity sector

While government-owned companies in Bangladesh generate nearly half of Bangladesh's electricity, privately-owned companies like the Summit Group and Orion Group are playing an increasingly important role in both generating electricity, and supplying machinery, reactors, and equipment.[344] Bangladesh increased electricity production from 5 gigawatts in 2009 to 25.5 gigawatts in 2022. It plans to produce 50 gigawatts by 2041. U.S. companies like Chevron and General Electric supply around 55% of Bangladesh’s domestic natural gas production and are among the largest investors in power projects. 80% of Bangladesh’s installed gas-fired power generation capacity comes from turbines manufactured in the United States.[345]

On 4 October 2022, the national grid collapsed and plunged the whole country into a nationwide blackout. The grid resumed operations after eight hours. The government's investigation focused on technical failure, negligence, and possible sabotage. The investigation found that grid capacity has not kept up with the expansion of electricity generation and the opening of new power plants.[346] Gas shortages were also to blame, including the lack of new gas sources and insufficient gas pipeline infrastructure. There was a shortage of natural gas because of the 2021–present global energy crisis as 77 natural gas power plants had insufficient fuel to meet demand. The electricity sector in Bangladesh is heavily reliant on natural gas.[347] Gas shortages forced the government to import LNG from abroad. As a result, Texas-based Excelerate Energy opened Bangladesh's first floating LNG terminal in 2018 off the coast of Maheshkhali Island.[348] The Summit LNG Terminal was opened in 2019.[349] The Government of Bangladesh has subsidized LNG imports worth several billion dollars. Since October 2021, Bangladesh imported LNG for US$30-37 per million Btu which is 10 times the price it paid in May 2020.[350] The government stopped buying spot price LNG in June 2022. The country's forex reserves declined due to surging fuel imports. Bangladesh imported 30% of its LNG on the spot price market in 2022, down from 40% in 2021. Bangladesh continues to trade in LNG on the futures exchange markets.[351]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 67,800,000 | — |

| 1980 | 80,600,000 | +1.94% |

| 1990 | 105,300,001 | +2.71% |

| 2000 | 129,600,000 | +2.10% |

| 2010 | 148,700,000 | +1.38% |

| 2012 | 161,100,200 | +4.09% |

| 2022 | 165,160,000 | +0.25% |

| Source: OECD/World Bank[352][6] | ||