Sri Lankan Tamils

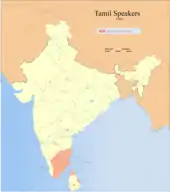

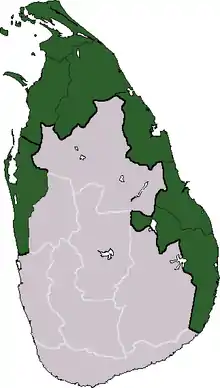

Sri Lankan Tamils (Tamil: இலங்கை தமிழர், ilankai tamiḻar or ஈழத் தமிழர், īḻat tamiḻar),[21] also known as Ceylon Tamils or Eelam Tamils, are Tamils native to the South Asian island state of Sri Lanka. Today, they constitute a majority in the Northern Province, live in significant numbers in the Eastern Province and are in the minority throughout the rest of the country. 70% of Sri Lankan Tamils in Sri Lanka live in the Northern and Eastern provinces.[1]

இலங்கை தமிழர் (ஈழத் தமிழர்) | |

|---|---|

A postcard image of a Sri Lankan Tamil lady from 1910. | |

| Total population | |

| ~ 3.0 million (estimated; excluding Moors and Indian Tamils) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,270,924 (2012)[1] | |

| ~300,000[2][3][4][5][6] | |

| ~120,000 (2006)[7] | |

| ~100,000 (2005)[8] | |

| ~60,000 (2008)[9] | |

| ~50,000 (2008)[10] | |

| ~35,000 (2006)[11] | |

| ~30,000 (1985)[12] | |

| ~30,000[13] | |

| ~25,000 (2010)[14] | |

| ~25,000[13] | |

| ~24,436 (1970)[15] | |

| ~20,000[13] | |

| ~10,000 (2000)[16] | |

| ~9,000 (2003)[17] | |

| Languages | |

| Languages of Sri Lanka: Tamil (and its Sri Lankan dialects) | |

| Religion | |

Majority:

Buddhism[19] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Tamils |

|---|

|

|

|

Modern Sri Lankan Tamils descend from residents of the Jaffna Kingdom, a former kingdom in the north of Sri Lanka and Vannimai chieftaincies from the east. According to the anthropological and archaeological evidence, Sri Lankan Tamils have a very long history in Sri Lanka and have lived on the island since at least around the 2nd century BCE.

The Sri Lankan Tamils are mostly Hindus with a significant Christian population. Sri Lankan Tamil literature on topics including religion and the sciences flourished during the medieval period in the court of the Jaffna Kingdom. Since the beginning of the Sri Lankan Civil War in the 1980s, it is distinguished by an emphasis on themes relating to the conflict. Sri Lankan Tamil dialects are noted for their archaism and retention of words not in everyday use in Tamil Nadu, India.

Since Sri Lanka gained independence from Britain in 1948, relations between the majority Sinhalese and minority Tamil communities have been strained. Rising ethnic and political tensions following the Sinhala Only Act, along with ethnic pogroms carried out by Sinhalese mobs in 1956, 1958, 1977, 1981 and 1983, led to the formation and strengthening of militant groups advocating independence for Tamils. The ensuing civil war resulted in the deaths of more than 100,000 people and the forced disappearance and rape of thousands of others. The civil war ended in 2009 but there are continuing allegations of atrocities being committed by the Sri Lankan military.[22][23][24] A United Nations panel found that as many as 40,000 Tamil civilians may have been killed in the final months of the civil war.[25] In January 2020, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa said that the estimated 20,000+ disappeared Sri Lankan Tamils were dead.[26] The end of the civil war has not fully improved conditions in Sri Lanka, with press freedom not being restored and the judiciary coming under political control.[27][28][29]

One-third of Sri Lankan Tamils now live outside Sri Lanka. While there was significant migration during the British colonial to Singapore and Malaysia, the civil war led to more than 800,000 Tamils leaving Sri Lanka, and many have left the country for destinations such as Canada, United Kingdom, Germany and India as refugees or emigrants. According to the pro-rebel TamilNet, the persecution and discrimination that Sri Lankan Tamils faced has resulted in some Tamils today not identifying themselves as Sri Lankans but instead identifying themselves as either Eelam Tamils, Ceylon Tamils, or simply Tamils.[30][31] Many still support the idea of Tamil Eelam, a proposed independent state that Sri Lankan Tamils aspired to create in the North-East of Sri Lanka.[32][33][34][35][36] Inspired by the Tamil Eelam flag, the tiger also used by the LTTE, has become a symbol of Tamil nationalism for some Tamils in Sri Lanka and the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora.[37][38]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Sri Lankan Tamils |

|---|

|

There is little scholarly consensus over the presence of the Sri Lankan Tamil people in Sri Lanka, also known as Eelam in Sangam literature.[39] One older theory states that there were no large Tamil settlements in Sri Lanka until the 10th century CE.[40] According to the anthropological and archaeological evidence, Sri Lankan Tamils have a very long history in Sri Lanka and have lived on the island since at least around the 2nd century BCE.[41][42]

Pre-historic period

The Indigenous Veddhas are ethnically related to people in South India and early populations of Southeast Asia. It is not possible to ascertain what languages that they originally spoke as Vedda language is considered diverged from its original source (due to Sinhalese language influence).[44]

According to K. Indrapala, cultural diffusion, rather than migration of people, spread the Prakrit and Tamil languages from peninsular India into an existing mesolithic population, centuries before the common era.[45] Tamil Brahmi and Tamil-Prakrit scripts were used to write the Tamil language during this period on the island.[46]

During the protohistoric period (1000-500 BCE) Sri Lanka was culturally united with southern India,[47] and shared the same megalithic burials, pottery, iron technology, farming techniques and megalithic graffiti.[48][49] This cultural complex spread from southern India along with Dravidian clans such as the Velir, prior to the migration of Prakrit speakers.[50][51][48]

Settlements of culturally similar early populations of ancient Sri Lanka and ancient Tamil Nadu in India were excavated at megalithic burial sites at Pomparippu on the west coast and in Kathiraveli on the east coast of the island. Bearing a remarkable resemblance to burials in the Early Pandyan Kingdom, these sites were established between the 5th century BCE and 2nd century CE.[43][52]

Excavated ceramic sequences similar to that of Arikamedu were found in Kandarodai (Kadiramalai) on the north coast, dated to 1300 BCE. Cultural similarities in burial practices in South India and Sri Lanka were dated by archaeologists to 10th century BCE. However, Indian history and archaeology have pushed the date back to 15th century BCE.[53] In Sri Lanka, there is radiometric evidence from Anuradhapura that the non-Brahmi symbol-bearing black and red ware occur in the 10th century BCE.[54]

The skeletal remains of an Early Iron Age chief were excavated in Anaikoddai, Jaffna District. The name Ko Veta is engraved in Brahmi script on a seal buried with the skeleton and is assigned by the excavators to the 3rd century BCE. Ko, meaning "King" in Tamil, is comparable to such names as Ko Atan, Ko Putivira and Ko Ra-pumaan occurring in contemporary Tamil Brahmi inscriptions of ancient South India and Egypt.[55][56]

Historic period

Potsherds with early Tamil writing from the 2nd century BCE have been found from the north in Poonagari, Kilinochchi District to the south in Tissamaharama. They bore several inscriptions, including a clan name—veḷ, a name related to velir from ancient Tamil country.[57]

Once Prakrit speakers had attained dominance on the island, the Mahavamsa further recounts the later migration of royal brides and service castes from the Tamil Pandya Kingdom to the Anuradhapura Kingdom in the early historic period.[58]

Epigraphic evidence shows people identifying themselves as Damelas or Damedas (the Prakrit word for Tamil people) in Anuradhapura, the capital city of Rajarata the middle kingdom, and other areas of Sri Lanka as early as the 2nd century BCE.[59] Excavations in the area of Tissamaharama in southern Sri Lanka have unearthed locally issued coins, produced between the 2nd century BCE and the 2nd century CE, some of which carry local Tamil personal names written in early Tamil characters,[60] which suggest that local Tamil merchants were present and actively involved in trade along the southern coast of Sri Lanka by the late classical period.[61]

Other ancient inscriptions from the period reference a Tamil merchant,[lower-alpha 1] the Tamil householder residing in Iḷabharata[lower-alpha 2] and a Tamil sailor named Karava.[lower-alpha 3] Two of the six ancient inscriptions referring to the Damedas (Tamils) are in Periya Pullyakulam in the Vavuniya District, one is in Seruvavila in Trincomalee District, one is in Kuduvil in Ampara District, one is in Anuradhapura and one is in Matale District.[62]

Mention is made in literary sources of Tamil rulers bringing horses to the island in water craft in the second century BCE, most likely arriving at Kudiramalai. Historical records establish that Tamil kingdoms in modern India were closely involved in the island's affairs from about the 2nd century BCE.[63][64] Kudiramalai, Kandarodai and Vallipuram served as great northern Tamil capitals and emporiums of trade with these kingdoms and the Romans from the 6th–2nd centuries BCE. The archaeological discoveries in these towns and the Manimekhalai, a historical poem, detail how Nāka-Tivu of Nāka-Nadu on the Jaffna Peninsula was a lucrative international market for pearl and conch trading for the Tamil fishermen.

In Mahavamsa, a historical poem, ethnic Tamil adventurers such as Ellalan invaded the island around 145 BCE.[65] Early Chola king Karikalan, son of Eelamcetcenni utilised superior Chola naval power to conquer Ceylon in the first century CE. Hindu Saivism, Tamil Buddhism and Jainism were popular amongst the Tamils at this time, as was the proliferation of village deity worship.

The Amaravati school was influential in the region when the Telugu Satavahana dynasty established the Andhra empire and its 17th monarch Hāla (20–24 CE) married a princess from the island. Ancient Vanniars settled in the east of the island in the first few centuries of the common era to cultivate and maintain the area.[66][67] The Vanni region flourished.[68]

In the 6th century CE, a special coastal route by boat was established from the Jaffna peninsula southwards to Saivite religious centres in Trincomalee (Koneswaram) and further south to Batticaloa (Thirukkovil), passed a few small Tamil trading settlements in Mullaitivu on the north coast.[69]

The conquests and rule of the island by Pallava king Narasimhavarman I (630–668 CE) and his grandfather King Simhavishnu (537–590 CE) saw the erection and structural development of several Kovils around the island, particularly in the north-east—these Pallava Dravidian rock temples remained a popular and highly influential style of architecture in the region over the next few centuries.[70][71][72] Tamil soldiers from what is now South India were brought to Anuradhapura between the 7th and 11th centuries CE in such large numbers that local chiefs and kings trying to establish legitimacy came to rely on them.[73] By the 8th century CE Tamil villages were collectively known as Demel-kaballa (Tamil allotment), Demelat-valademin (Tamil villages), and Demel-gam-bim (Tamil villages and lands).[74]

Medieval period

In the 9th and 10th centuries CE, Pandya and Chola incursions into Sri Lanka culminated in the Chola annexation of the island, which lasted until the latter half of the 11th century CE.[73][76][77][78][79][80] Raja Raja Chola I renamed the northern throne Mummudi Chola Mandalam after his conquest of the northeast country to protect Tamil traders being looted, imprisoned and killed for years on the island.[81] Rajadhiraja Chola's conquest of the island led to the fall of four kings there, one of whom, Madavarajah, the king of Jaffna, was a usurper from the Rashtrakuta Dynasty.[82] These dynasties oversaw the development of several Kovils that administered services to communities of land assigned to the temples through royal grants. Their rule also saw the benefaction of other faiths. Recent excavations have led to the discovery of a limestone Kovil of Raja Raja Chola I's era on Delft island, found with Chola coins from this period.[83] The decline of Chola power in Sri Lanka was followed by the restoration of the Polonnaruwa monarchy in the late 11th century CE.[84]

In 1215, following Pandya invasions, the Tamil-dominant Arya Chakaravarthi dynasty established an independent Jaffna kingdom on the Jaffna peninsula and other parts of the north.[85] The Arya Chakaravarthi expansion into the south was halted by Alagakkonara,[86] a man descended from a family of merchants from Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu. He was the chief minister of the Sinhalese king Parakramabahu V (1344–59 CE). Vira Alakeshwara, a descendant of Alagakkonara, later became king of the Sinhalese,[87] but he was overthrown by the Ming admiral Zheng He in 1409 CE. The next year, the Chinese admiral Zheng He erected a trilingual stone tablet in Galle in the south of the island, written in Chinese, Persian and Tamil that recorded offerings he made to Buddha, Allah and the God of Tamils Tenavarai Nayanar. The admiral invoked the blessings of Hindu deities at Temple of Perimpanayagam Tenavaram, Tevanthurai for a peaceful world built on trade.[88]

The 1502 map Cantino represents three Tamil cities on the east coast of the island - Mullaitivu, Trincomalee and Panama, where the residents grow cinnamon and other spices, fish for pearls and seed pearls and worship idols, trading heavily with Kozhikode of Kerala.[89] The Arya Chakaravarthi dynasty ruled large parts of northeast Sri Lanka until the Portuguese conquest of the Jaffna kingdom in 1619 CE. The coastal areas of the island were conquered by the Dutch and then became part of the British Empire in 1796 CE.

The Sinhalese Nampota dated in its present form to the 14th or 15th century CE suggests that the whole of the Tamil Kingdom, including parts of the modern Trincomalee District, was recognised as a Tamil region by the name Demala-pattana (Tamil city).[90] In this work, a number of villages that are now situated in the Jaffna, Mullaitivu and Trincomalee districts are mentioned as places in Demala-pattana.[91]

The English sailor Robert Knox described walking into the island's Tamil country in the publication An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon, referencing some aspects of their royal, rural and economic life and annotating some kingdoms within it on a map in 1681 CE.[92] Upon arrival of European powers from the 17th century CE, the Tamils' separate nation was described in their areas of habitation in the northeast of the island.[lower-alpha 4]

The caste structure of the majority Sinhalese has also accommodated Tamil and Kerala immigrants from South India since the 13th century CE. This led to the emergence of three new Sinhalese caste groups: the Salagama, the Durava and the Karava.[93][94][95] The Tamil migration and assimilation continued until the 18th century CE.[93]

Society

Demographics

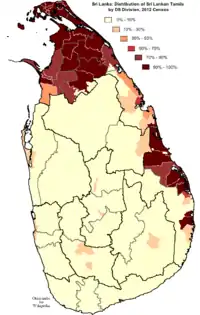

According to the 2012 census there were 2,270,924 Sri Lankan Tamils in Sri Lanka, 11.2% of the population.[1] Sri Lankan Tamils constitute an overwhelming majority of the population in the Northern Province and are the largest ethnic group in the Eastern Province.[1] They are minority in other provinces. 70% of Sri Lankan Tamils in Sri Lanka live in the Northern and Eastern provinces.[1]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1911 | 528,000 | — |

| 1921 | 517,300 | −2.0% |

| 1931 | 598,900 | +15.8% |

| 1946 | 733,700 | +22.5% |

| 1953 | 884,700 | +20.6% |

| 1963 | 1,164,700 | +31.6% |

| 1971 | 1,424,000 | +22.3% |

| 1981 | 1,886,900 | +32.5% |

| 1989 | 2,124,000 | +12.6% |

| 2012 | 2,270,924 | +6.9% |

| Source: [1][96][97][lower-alpha 5] | ||

| Province | Sri Lankan Tamils |

% Province |

% Sri Lankan Tamils |

|---|---|---|---|

| 128,263 | 5.0% | 5.7% | |

| 609,584 | 39.3% | 26.8% | |

| 987,692 | 93.3% | 43.5% | |

| 12,421 | 1.0% | 0.6% | |

| 66,286 | 2.8% | 2.9% | |

| 74,908 | 3.9% | 3.3% | |

| 25,901 | 1.1% | 1.1% | |

| 30,118 | 2.4% | 1.3% | |

| 335,751 | 5.8% | 14.8% | |

| Total | 2,270,924 | 11.2% | 100.0% |

There are no accurate figures for the number of Sri Lankan Tamils living in the diaspora. Estimates range from 450,000 to one million.[98][99]

Other Tamil-speaking communities

The two groups of Tamils located in Sri Lanka are the Sri Lankan Tamils and the Indian Tamils. There also exists a significant population in Sri Lanka who are native speakers of Tamil language and are of Islamic faith. Though a significant amount of evidence points towards these Muslims being ethnic Tamils,[100][101][102] they are controversially[100][102][103] listed as a separate ethnic group by the Sri Lankan government.[104][105][106]

Sri Lankan Tamils (also called Ceylon Tamils) are descendants of the Tamils of the old Jaffna Kingdom and east coast chieftaincies called Vannimais. The Indian Tamils (or Hill Country Tamils) are descendants of bonded labourers sent from Tamil Nadu to Sri Lanka in the 19th century to work on tea plantations.[107][108]

Most Sri Lankan Tamils live in the Northern and Eastern provinces and in the capital Colombo, and most Indian Tamils live in the central highlands.[106] Historically, both groups have seen themselves as separate communities, although there has been a greater sense of unity since the 1980s.[109] In 1948, the United National Party government stripped the Indian Tamils of their citizenship. Under the terms of an agreement reached between the Sri Lankan and Indian governments in the 1960s, about forty percent of the Indian Tamils were granted Sri Lankan citizenship, and most of the remainder were repatriated to India.[110] By the 1990s, most Indian Tamils had received Sri Lankan citizenship.[110]

Regional groups

Sri Lankan Tamils are categorised into three subgroups based on regional distribution, dialects, and culture: Negombo Tamils from the western part of the island, Eastern Tamils from the eastern part, and Jaffna or Northern Tamils from the north.

Eastern Tamils

Eastern Tamils inhabit a region that spans the Trincomalee, Batticaloa, and Ampara districts.[112] Their history and traditions are inspired by local legends, native literature, and colonial documents.[113]

In the 16th century the area came under the nominal control of the Kingdom of Kandy, but there was scattered leadership under Vannimai chiefs in Batticaloa District[114][115] who came with Magha's army in 1215.[116] From that time on, Eastern Tamil social development diverged from that of the Northern Tamils.

Eastern Tamils are an agrarian-based society. They follow a caste system similar to the South Indian or Dravidian kinship system. The Eastern Tamil caste hierarchy is dominated by the Mukkuvar, Vellalar and Karaiyar.[117] The main feature of their society is the kudi system.[118] Although the Tamil word kudi means a house or settlement, in eastern Sri Lanka it is related to matrimonial alliances. It refers to the exogamous matrilineal clans and is found amongst most caste groups.[119] Men or women remain members of the kudi of their birth and be brother or sister by relation. No man can marry in the same kudi because woman is always become sister to him. But, a man can only marry in one of his sampantha kudis not in the sakothara kudis. By custom, children born in a family belong to mother's kudi. Kudi also collectively own places of worship such as Hindu temples.[119] Each caste contains a number of kudis, with varying names. Aside from castes with an internal kudi system, there are seventeen caste groups, called Ciraikudis, or imprisoned kudis, whose members were considered to be in captivity, confined to specific services such as washing, weaving, and toddy tapping. However, such restrictions no longer apply.

The Tamils of the Trincomalee district have different social customs from their southern neighbours due to the influence of the Jaffna kingdom to the north.[119] The indigenous Veddha people of the east coast also speak Tamil and have become assimilated into the Eastern Tamil caste structure.[120] Most Eastern Tamils follow customary laws called Mukkuva laws codified during the Dutch colonial period.[121]

Northern Tamils

Jaffna's history of being an independent kingdom lends legitimacy to the political claims of the Sri Lankan Tamils, and has provided a focus for their constitutional demands.[122] Northern Tamil society is generally categorised into two groups: those who are from the Jaffna peninsula in the north, and those who are residents of the Vanni to the immediate south. The Jaffna society is separated by castes. Historically, the Sri Lankan Vellalar were in northern region dominant and were traditionally husbandman involved in agriculture and cattle cultivation.[123] They constitute half of the population and enjoyed dominance under Dutch rule, from which community the colonial political elites also were drawn from.[124] The maritime communities existed outside the agriculture-based caste system and is dominated by the Karaiyars.[125][126] The dominant castes (e.g. the Vellalar or Karaiyar) traditionally use the service of those collectively known as Kudimakkal. The Panchamars, who serve as Kudimakkal, consists of the Nalavar, Pallar, Parayar, Vannar and Ambattar.[122] The castes of temple priests known as the Kurukkals and the Iyers are also held in high esteem.[125] The artisans who are known as Kammalar also serve as Kudimakkal, and consists of the Kannar (brass-workers), Kollar (blacksmiths), Tattar (goldsmiths), Tatchar (carpenters) and Kartatchar (sculptor). The Kudimakkal were domestic servants who also gave ritual importance to the dominant castes.[127][128]

People in the Vanni districts considered themselves separate from Tamils of the Jaffna peninsula but the two groups did intermarry. Most of these married couples moved into the Vanni districts where land was available. Vanni consists of a number of highland settlements within forested lands using irrigation tank-based cultivation. An 1890 census listed 711 such tanks in this area. Hunting and raising livestock such as water buffalo and cattle is a necessary adjunct to the agriculture. The Tamil-inhabited Vanni consists of the Vavuniya, Mullaitivu, and eastern Mannar districts. Historically, the Vanni area has been in contact with what is now South India, including during the medieval period and was ruled by the Vanniar Chieftains.[122] Northern Tamils follow customary laws called Thesavalamai, codified during the Dutch colonial period.[129]

Western Tamils

Western Tamils, also known as Negombo Tamils or Puttalam Tamils, are native Sri Lankan Tamils who live in the western Gampaha and Puttalam districts. The term does not apply to Tamil immigrants in these areas.[130] They are distinguished from other Tamils by their dialects, one of which is known as the Negombo Tamil dialect, and by aspects of their culture such as customary laws.[130][131][132] Most Negombo Tamils have assimilated into the Sinhalese ethnic group through a process known as Sinhalisation. Sinhalisation has been facilitated by caste myths and legends.[133] The Western Tamils caste hierarchy is principally dominated by the maritime Karaiyars, along with other dominant groups such as the Paravars.[134]

In Gampaha District, Tamils have historically inhabited the coastal region. In the Puttalam District, there was a substantial ethnic Tamil population until the first two decades of the 20th century.[133][135] Most of those who identify as ethnic Tamils live in villages such as Udappu and Maradankulam.[136] The coastal strip from Jaffna to Chilaw is also known as the "Catholic belt".[137] The Tamil Christians, chiefly Roman Catholics, have preserved their heritage in the major cities such as Negombo, Chilaw, Puttalam, and also in villages such as Mampuri.[133]

Some residents of these two districts, especially the Karaiyars, are bilingual, ensuring that the Tamil language survives as a lingua franca among migrating maritime communities across the island. Negombo Tamil dialect is spoken by about 50,000 people. This number does not include others, outside of Negombo city, who speak local varieties of the Tamil language.[131] The bilingual catholic Karavas are also found in the western coastal regions, who trace their origins to the Tamil Karaiyar however identify themselves as Sinhalese.[138]

Negombo Tamil is the fact that the Karavas immigrated to Sri Lanka much later than Tamils immigrated to Jaffna. This would suggest that the Negombo dialect continued to evolve in the Coromandel Coast before it arrived in Sri Lanka and began to get influenced by Sinhala. So, in some ways, the dialect is closer to those spoken in Tamil Nadu than is Jaffna Tamil.[139]

Some Tamil place names have been retained in these districts. Outside the Tamil-dominated northeast, the Puttalam District has the highest percentage of place names of Tamil origin in Sri Lanka. Composite or hybrid place names are also present in these districts.[140]

Genetic affinities

Although Sri Lankan Tamils are culturally and linguistically distinct, genetic studies indicate that they are closely related to other ethnic groups in the island while being related to the Indian Tamils from South India as well. There are various studies that indicate varying degrees of connections between Sri Lankan Tamils, Sinhalese, and Indian ethnic groups.

A study conducted by Kshatriya in 1995 found that both ethnolinguistic groups of Sri Lanka, including the Tamils, were closest to the Tamil population of India and also the Muslim population of South India. They were found to be the most distant group from the Veddahs, and quite distant from both North-West Indians (Punjabis and Gujratis) and North-East Indians (Bengalis).[141]

In comparison to Indian Tamils, the Tamils of Sri Lanka had a higher admixture with the Sinhalese, though the Sinhalese themselves share a 69.86% (+/- 0.61) genetic admixture with the Indian Tamils. However, the study was carried out using Sinhalese from regions where Sinhala–-Tamil interactions were higher and older methods compared to other modern and accurate studies.[141] The study stated that any admixture from migrations several thousand years ago must have been erased through millennia of admixture among geographically local peoples.[141]

An Alu polymorphism analysis of Sinhalese from Colombo by Dr Sarabjit Mastanain in 2007 using Tamil, Bengali, Gujarati (Patel), and Punjabi as parental populations found that Sinhalese share 11-30% of their genes with the Tamils.[142]

Another VNTR study found that 16-30% of Sinhalese genes are shared with the Tamils.[143]

Religion

_-_Copy.jpg.webp)

In 1981, about eighty percent of Sri Lankan Tamils were Hindus who followed the Shaiva sect.[145] The rest were mostly Roman Catholics who converted after the Portuguese conquest of Jaffna Kingdom. There is also a small minority of Protestants due to missionary efforts in the 18th century by organisations such as the American Ceylon Mission.[146] Most Tamils who inhabit the Western Province are Roman Catholics, while those of the Northern and Eastern Provinces are mainly Hindu.[147] Pentecostal and other churches, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, are active among the internally displaced and refugee populations.[148] The 2012 Sri Lanka Census revealed a Buddhist population of 22,254 amongst Sri Lankan Tamils, i.e. roughly 1% of all Sri Lankan Tamils in Sri Lanka.[18]

The Hindu elite, especially the Vellalar, follow the religious ideology of Shaiva Siddhanta (Shaiva school) while the masses practice folk Hinduism, upholding their faith in local village deities not found in formal Hindu scriptures. The place of worship depends on the object of worship and how it is housed. It could be a proper Hindu temple known as a Koyil, constructed according to the Agamic scripts (a set of scriptures regulating the temple cult). More often, however, the temple is not completed in accordance with Agamic scriptures but consists of the barest essential structure housing a local deity.[147] These temples observe daily Puja (prayers) hours and are attended by locals. Both types of temples have a resident ritualist or priest known as a Kurukkal. A Kurukkal may belong to someone from a prominent local lineage like Pandaram or Iyer community.[147] In the Eastern Province, a Kurukkal usually belongs to Lingayat sect. Other places of worship do not have icons for their deities. The sanctum could house a trident (culam), a stone, or a large tree. Temples of this type are common in the Northern and Eastern Provinces; a typical village has up to 150 such structures. The offering would be done by an elder of the family who owns the site. A coconut oil lamp would be lit on Fridays, and a special rice dish known as pongal would be cooked either on a day considered auspicious by the family or on the Thai Pongal day, and possibly on Tamil New Year Day.

There are several worshipped deities: Ayyanar, Annamar, Vairavar, Kali, Pillaiyar, Murukan, Kannaki Amman and Mariamman. Villages have more Pillaiyar temples, which are patronised by local farmers.[147] Kannaki Amman is mostly patronised by maritime communities.[149] Tamil Roman Catholics, along with members of other faiths, worship at the Shrine of Our Lady of Madhu.[150] Hindus have several temples with historic importance such as those at Ketheeswaram, Koneswaram, Naguleswaram, Munneswaram, Tondeswaram, and Nallur Kandaswamy.[151] Kataragama temple and Adam's Peak are attended by all religious communities.

Language

Sri Lankan Tamils predominantly speak Tamil and its Sri Lankan dialects. These dialects are differentiated by the phonological changes and sound shifts in their evolution from classical or old Tamil (3rd century BCE–7th century CE). The Sri Lankan Tamil dialects form a group that is distinct from the dialects of the modern Tamil Nadu and Kerala states of India. They are classified into three subgroups: the Jaffna Tamil, the Batticaloa Tamil, and the Negombo Tamil dialects. These dialects are also used by ethnic groups other than Tamils such as the Sinhalese, Moors and Veddhas. Tamil loan words in Sinhala also follow the characteristics of Sri Lankan Tamil dialects.[152] Sri Lankan Tamils, depending on where they live in Sri Lanka, may also additionally speak Sinhala and or English. According to the 2012 Census 32.8% or 614,169 Sri Lankan Tamils also spoke Sinhala and 20.9% or 390,676 Sri Lankan Tamils also spoke English.[153]

The Negombo Tamil dialect is used by bilingual fishermen in the Negombo area, who otherwise identify themselves as Sinhalese. This dialect has undergone considerable convergence with spoken Sinhala.[132] The Batticaloa Tamil dialect is shared between Tamils, Muslims, Veddhas and Portuguese Burghers in the Eastern Province. Batticaloa Tamil dialect is the most literary of all the spoken dialects of Tamil. It has preserved several ancient features, remaining more consistent with the literary norm, while at the same time developing a few innovations. It also has its own distinctive vocabulary and retains words that are unique to present-day Malayalam, a Dravidian language from Kerala that originated as a dialect of old Tamil around 9th century CE.[154][155] The Tamil dialect used by residents of the Trincomalee District has many similarities with the Jaffna Tamil dialect.[152]

The dialect used in Jaffna is the oldest and closest to old Tamil. The long physical isolation of the Tamils of Jaffna has enabled their dialect to preserve ancient features of old Tamil that predate Tolkappiyam,[152] the grammatical treatise on Tamil dated from 3rd century BCE to 10th century CE.[156] Also, a large component of the settlers were from the Coromandel Coast and Malabar Coast which may have helped with the preservation of the dialect.[157][158] Their ordinary speech is closely related to classical Tamil.[152] Conservational Jaffna Tamil dialect and Indian Tamil dialects are to an extent not mutually intelligible,[159] and the former is frequently mistaken for Malayalam by native Indian Tamil speakers. [160] The closest Tamil Nadu Tamil variant to Jaffna Tamil is literary Tamil, used in formal speeches and news reading. There are also Prakrit loan words that are unique to Jaffna Tamil.[161][162]

Education

Sri Lankan Tamil society values education highly, for its own sake as well as for the opportunities it provides.[131] The kings of the Aryacakravarti dynasty were historically patrons of literature and education. Temple schools and traditional gurukulam classes on verandahs (known as Thinnai Pallikoodam in Tamil) spread basic education in religion and in languages such as Tamil and Sanskrit to the upper classes.[163] The Portuguese introduced western-style education after their conquest of the Jaffna kingdom in 1619. The Jesuits opened churches and seminaries, but the Dutch destroyed them and opened their own schools attached to Dutch Reformed churches when they took over Tamil-speaking regions of Sri Lanka.[164]

The primary impetus for educational opportunity came with the establishment of the American Ceylon Mission in Jaffna District, which started with the arrival in 1813 of missionaries sponsored by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. The critical period of the missionaries' impact was from the 1820s to the early 20th century. During this time, they created Tamil translations of English texts, engaged in printing and publishing, established primary, secondary, and college-level schools, and provided health care for residents of the Jaffna Peninsula. American activities in Jaffna also had unintended consequences. The concentration of efficient Protestant mission schools in Jaffna produced a revival movement among local Hindus led by Arumuga Navalar, who responded by building many more schools within the Jaffna peninsula. Local Catholics also started their own schools in reaction, and the state had its share of primary and secondary schools. Tamil literacy greatly increased as a result of these changes. This prompted the British colonial government to hire Tamils as government servants in British-held Ceylon, India, Malaysia, and Singapore.[165]

By the time Sri Lanka became independent in 1948, about sixty percent of government jobs were held by Tamils, who formed barely fifteen percent of the population. The elected Sinhalese leaders of the country saw this as the result of a British stratagem to control the majority Sinhalese, and deemed it a situation that needed correction by implementation of the Policy of standardization.[166][167]

Literature

According to legends, the origin of Sri Lankan Tamil literature dates back to the Sangam period (3rd century BCE–6th century CE). These legends indicate that the Tamil poet Eelattu Poothanthevanar (Poothanthevanar from Sri Lanka) lived during this period.[168]

Medieval period Tamil literature on the subjects of medicine, mathematics and history was produced in the courts of the Jaffna Kingdom. During Singai Pararasasekaran's rule, an academy for the propagation of the Tamil language, modelled on those of ancient Tamil Sangam, was established in Nallur. This academy collected manuscripts of ancient works and preserved them in the Saraswathy Mahal library.[163][169]

During the Portuguese and Dutch colonial periods (1619–1796), Muttukumara Kavirajar is the earliest known author who used literature to respond to Christian missionary activities. He was followed by Arumuga Navalar, who wrote and published a number of books.[168] The period of joint missionary activities by the Anglican, American Ceylon, and Methodist Missions also saw the spread of modern education and the expansion of translation activities.

The modern period of Tamil literature began in the 1960s with the establishment of modern universities and a free education system in post-independence Sri Lanka. The 1960s also saw a social revolt against the caste system in Jaffna, which impacted Tamil literature: Dominic Jeeva, Senkai aazhiyaan, Thamizhmani Ahalangan are the products of this period.[168]

After the start of the civil war in 1983, a number of poets and fiction writers became active, focusing on subjects such as death, destruction, and rape. Such writings have no parallels in any previous Tamil literature.[168] The war produced displaced Tamil writers around the globe who recorded their longing for their lost homes and the need for integration with mainstream communities in Europe and North America.[168]

The Jaffna Public Library which contained over 97,000 books and manuscripts was one of the biggest libraries in Asia, and through the Burning of the Jaffna Public Library much of Sri Lankan Tamil literature has been obliterated.[170]

Cuisine

The cuisine of Sri Lankan Tamils draws influence from that of India, as well as from colonialists and foreign traders. Rice is usually consumed daily and can be found at any special occasion, while spicy curries are favourite dishes for lunch and dinner. Rice and curry is the name for a range of Sri Lankan Tamil dishes distinct from Indian Tamil cuisine, with regional variations between the island's northern and eastern areas. While rice with curries is the most popular lunch menu, combinations such as curd, tangy mango, and tomato rice are also commonly served.[171]

String hoppers, which are made of rice flour and look like knitted vermicelli neatly laid out in circular pieces about 12 centimetres (4.7 in) in diameter, are frequently combined with tomato sothi (a soup) and curries for breakfast and dinner.[172] Another common item is puttu, a granular, dry, but soft steamed rice powder cooked in a bamboo cylinder with the base wrapped in cloth so that the bamboo flute can be set upright over a clay pot of boiling water. This can be transformed into varieties such as ragi, spinach, and tapioca puttu. There are also sweet and savoury puttus.[173] Another popular breakfast or dinner dish is Appam, a thin crusty pancake made with rice flour, with a round soft crust in the middle.[174] It has variations such as egg or milk Appam.[171]

Jaffna, as a peninsula, has an abundance of seafood such as crab, shark, fish, prawn, and squid. Meat dishes such as mutton, chicken and pork also have their own niche. Vegetable curries use ingredients primarily from the home garden such as pumpkin, yam, jackfruit seed, hibiscus flower, and various green leaves. Coconut milk and hot chilli powder are also frequently used. Appetizers can consist of a range of achars (pickles) and vadahams. Snacks and sweets are generally of the homemade "rustic" variety, relying on jaggery, sesame seed, coconut, and gingelly oil, to give them their distinct regional flavour. A popular alcoholic drink in rural areas is palm wine (toddy), made from palmyra tree sap. Snacks, savouries, sweets and porridge produced from the palmyra form a separate but unique category of foods; from the fan-shaped leaves to the root, the palmyra palm forms an intrinsic part of the life and cuisine of northern region.[171]

Politics

Sri Lanka became an independent nation in 1948. Since independence, the political relationship between the Sinhalese and Sri Lankan Tamil communities has been strained. Sri Lanka has been unable to contain its ethnic violence as it escalated from sporadic terrorism to mob violence, and finally to civil war.[175] The Sri Lankan Civil War has several underlying causes: the ways in which modern ethnic identities have been made and remade since the colonial period, rhetorical wars over archaeological sites and place name etymologies, and the political use of the national past.[94] The civil war resulted in the death of at least 100,000 people[176][177] and, according to human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch, the forced disappearance of thousands of others (see White van abductions in Sri Lanka).[178][179][180] Since 1983, Sri Lanka has also witnessed massive civilian displacements of more than a million people, with eighty percent of them being Sri Lankan Tamils.[181]

Before independence

The arrival of Protestant missionaries on a large scale beginning in 1814 was a primary contributor to the development of political awareness among Sri Lankan Tamils. Activities by missionaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and Methodist and Anglican churches led to a revival among Hindu Tamils who created their own social groups, built their own schools and temples, and published their own literature to counter the missionary activities. The success of this effort led to a new confidence for the Tamils, encouraging them to think of themselves as a community, and it paved the way for their emergence as a cultural, religious, and linguistic society in the mid-19th century.[182][183]

Britain, which conquered the whole island by 1815, established a legislative council in 1833. During the 1833 Colebrooke-Cameron reforms the British centralised control to Colombo and amalgamated all administrative territories including the Tamil areas which had previously been administered separately.[184] A form of modern central government was established for the first time in the island, followed by gradual decline of local form of feudalism including Rajakariya, which was abolished soon after.

In the legislative council the British assigned three European seats and one seat each for Sinhalese, Tamils and Burghers.[185] This council's primary function was to act as advisor to the Governor, and the seats eventually became elected positions.[186] There was initially little tension between the Sinhalese and the Tamils, when in 1913 Ponnambalam Arunachalam, a Tamil, was elected representative of the Sinhalese as well as of the Tamils in the national legislative council. British Governor William Manning, who was appointed in 1918 however, actively encouraged the concept of "communal representation".[187] Subsequently, the Donoughmore Commission in 1931 rejected communal representation and brought in universal franchise. This decision was opposed by the Tamil political leadership, who realised that they would be reduced to a minority in parliament according to their proportion of the overall population. In 1944, G. G. Ponnambalam, a leader of the Tamil community, suggested to the Soulbury Commission that a roughly equal number of seats be assigned to Sinhalese and minorities in an independent Ceylon (50:50)—a proposal that was rejected.[188] But under section 29(2) of the constitution formulated by the commissioner, additional protection was provided to minority groups, such requiring a two-thirds majority for any amendments and a scheme of representation that provided more weight to the ethnic minorities.[189]

After independence

Shortly after independence in 1948, G.G. Ponnambalam and his All Ceylon Tamil Congress joined D.S. Senanayake's moderate, western-oriented United National Party led government which led to a split in the Tamil Congress.[190] S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, the leader of the splinter Federal Party (FP or Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi), contested the Ceylon Citizenship Act, which denied citizenship to Tamils of recent Indian origin, before the Supreme Court, and then in the Privy council in England, but failed to overturn it. The FP eventually became the dominant Tamil political party.[191] In response to the Sinhala Only Act in 1956, which made Sinhala the sole official language, Federal Party Members of Parliament staged a nonviolent sit-in (satyagraha) protest, but it was violently broken up by a mob. The FP was blamed and briefly banned after the riots of May–June 1958 targeting Tamils, in which many were killed and thousands forced to flee their homes.[192] Another point of conflict between the communities was state sponsored colonisation schemes that effectively changed the demographic balance in the Eastern Province, an area Tamil nationalists considered to be their traditional homeland, in favour of the majority Sinhalese.[175][193]

In 1972, a newly formulated constitution removed section 29(2) of the 1947 Soulbury constitution that was formulated to protect the interests of minorities.[189] Also, in 1973, the Policy of standardization was implemented by the Sri Lankan government, supposedly to rectify disparities in university enrolment created under British colonial rule. The resultant benefits enjoyed by Sinhalese students also meant a significant decrease in the number of Tamil students within the Sri Lankan university student population.[194]

Shortly thereafter, in 1973, the Federal Party decided to demand a separate Tamil state. In 1976 they merged with the other Tamil political parties to become the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). [195] [175][193] By 1977 most Tamils seemed to support the move for independence by electing the Tamil United Liberation Front overwhelmingly.[196] The elections were followed by the 1977 riots, in which around 300 Tamils were killed.[197] There was further violence in 1981 when an organised Sinhalese mob went on a rampage during the nights of 31 May to 2 June, burning down the Jaffna public library—at the time one of the largest libraries in Asia—containing more than 97,000 books and manuscripts.[198][199]

Rise of militancy

Since 1948, successive governments have adopted policies that had the net effect of assisting the Sinhalese community in such areas as education and public employment.[200] These policies made it difficult for middle class Tamil youth to enter university or secure employment.[200][201]

The individuals belonging to this younger generation, often referred to by other Tamils as "the boys" (Podiyangal in Tamil), formed many militant organisations.[200] The most important contributor to the strength of the militant groups was the Black July massacre, in which between 1,000 and 3,000[202][203] Tamils were killed, prompting many youths to choose the path of armed resistance.[200][203][204]

By the end of 1987, the militant youth groups had fought not only the Sri Lankan security forces and the Indian Peace Keeping Force also among each other, with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) eventually eliminating most of the others. Except for the LTTE, many of the remaining organisations transformed into either minor political parties within the Tamil National Alliance or standalone political parties. Some also function as paramilitary groups within the Sri Lankan military.[200]

Human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as the United States Department of State[205] and the European Union,[206] have expressed concern about the state of human rights in Sri Lanka, and both the government of Sri Lanka and the rebel LTTE have been accused of human rights violations. Although Amnesty International in 2003 found considerable improvement in the human rights situation, attributed to a ceasefire and peace talks between the government and the LTTE,[207] by 2007 they reported an escalation in political killings, child recruitment, abductions, and armed clashes, which created a climate of fear in the north and east of the country.[208]

End of the civil war

In August 2009, the civil war ended with total victory for the government forces. During the last phase of the war, many Tamil civilians and combatants were killed. The government estimated that over 22,000 LTTE cadres had died.[209] The civilian death toll is estimated to be as high as 40,000 or more.[210] This is in addition to the 70,000 Sri Lankans killed up to the beginning of the last phase of the civil war.[211] Over 300,000 internally displaced Tamil civilians were interred in special camps and eventually released. As of 2011, there were still a few thousand alleged combatants in state prisons awaiting trials.[212] The Sri Lankan government has released over 11,000 rehabilitated former LTTE cadres.[213]

Bishop of Mannar (a northwestern town) Rayappu Joseph said that 146,679 people seemed to be unaccounted between 2008 October and at the end of the civil war.[214]

The Tamil presence in Sri Lankan politics and society is facing a revival. In 2015 elections the Tamil national alliance got the third largest number of seats in the Parliament and as the largest parties UNP and SLFP created a unity government TNA leader R. Sampanthan was appointed as the opposition leader.[215][216] K. Sripavan became the 44th Chief justice and the second Tamil to hold the position.[217]

Migrations

Pre-independence

The earliest Tamil speakers from Sri Lanka known to have travelled to foreign lands were members of a merchant guild called Tenilankai Valanciyar (Valanciyar from Lanka of the South). They left behind inscriptions in South India dated to the 13th century.[218] In the late 19th century, educated Tamils from the Jaffna peninsula migrated to the British colonies of Malaya (Malaysia and Singapore) and India to assist the colonial bureaucracy. They worked in almost every branch of public administration, as well as on plantations and in industrial sectors. Prominent Sri Lankan Tamils in the Forbes list of billionaire include: Ananda Krishnan,[219] Raj Rajaratnam, and G. Gnanalingam,[220] and Singapore's former foreign minister and deputy prime minister, S. Rajaratnam, are of Sri Lankan Tamil descent.[221] C. W. Thamotharampillai, an Indian-based Tamil language revivalist, was born in the Jaffna peninsula.[222]Before the Sri Lankan civil war, Sri Lankan Tamil communities were well established in Malaysia, Singapore, India and the UK.

Post civil war

After the start of the conflict between the Sri Lankan government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, there was a mass migration of Tamils trying to escape the hardships and perils of war. Initially, it was middle class professionals, such as doctors and engineers, who emigrated; they were followed by the poorer segments of the community. The fighting drove more than 800,000 Tamils from their homes to other places within Sri Lanka as internally displaced persons and also overseas, prompting the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to identify them in 2004 as the largest asylum-seeking group.[8][223]

The country with the largest share of displaced Tamils is Canada, with more than 200,000 legal residents,[2] found mostly within the Greater Toronto Area.[224] and there are a number of prominent Canadians of Sri Lankan Tamil descent, such as author Shyam Selvadurai,[225] and Indira Samarasekera,[226] former president of the University of Alberta.

Sri Lankan Tamils in India are mostly refugees of about over 100,000 in special camps and another 50,000 outside of the camps.[8] In western European countries, the refugees and immigrants have integrated themselves into society where permitted. Tamil British singer M.I.A (born Mathangi Arulpragasam)[227] and BBC journalist George Alagiah[228] are, among others, notable people of Sri Lankan Tamil descent. Sri Lankan Tamil Hindus have built a number of prominent Hindu temples across North America and Europe, notably in Canada, France, Germany, Denmark, and the UK.[9][17]

Sri Lankan Tamils continue to seek refuge in countries like Canada and Australia.[229][230] The International Organization for Migration and the Australian government has declared some Sri Lankans including Tamils as economic migrants.[231] A Canadian government survey found that over 70% of Sri Lankan Tamil refugees have gone back to Sri Lanka for holidays raising concerns over the legitimacy of their refugee claims.[232]

See also

- List of Sri Lankan Tamils

- Sri Lankan Tamils in Indian cinema

- Tamil inscriptions in Sri Lanka

Notes

- Dameda vanija gahapati Vishaka.

- Iḷa bharatahi Dameda Samane karite Dameda gahapathikana.

- Dameda navika karava.

- Upon arrival in June 1799, Sir Hugh Cleghorn, the island's first British colonial secretary wrote to the British government of the traits and antiquity of the Tamil nation on the island in the Cleghorn Minute: "Two different nations from a very ancient period have divided between them the possession of the island. First the Sinhalese, inhabiting the interior in its Southern and Western parts, and secondly the Malabars [another name for Tamils] who possess the Northern and Eastern districts. These two nations differ entirely in their religion, language, and manners". McConnell, D., 2008; Ponnambalam, S. 1983

- Data is based on Sri Lankan Government census except 1989 which is an estimate.

References

- "A2 : Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012". Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka.

- Foster, Carly (2007). "Tamils: Population in Canada". Ryerson University. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

According to government figures, there are about 200,000 Tamils in Canada

- "Linguistic Characteristics of Canadians".

- "Tamils by the Numbers". Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- "New bilingualism taking hold in Canada".

- "Table 1 Size and percentage of population that reported speaking one of the top 12 immigrant languages most often at home in the six largest census metropolitan areas, 2011".

- "Britain urged to protect Tamil Diaspora". BBC Sinhala. 15 March 2006.

According to HRW, there are about 120,000 Sri Lankan Tamils in the UK.

- Acharya, Arunkumar (2007). "Ethnic conflict and refugees in Sri Lanka" (PDF). Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- Baumann, Martin (2008). "Immigrant Hinduism in Germany: Tamils from Sri Lanka and Their Temples". Harvard University. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

Since the escalation of the Sinhalese-Tamil conflict in Sri Lanka during the 1980s, about 60,000 came as asylum seekers.

- "Politically French, culturally Tamil: 12 Tamils elected in Paris and suburbs". TamilNet. 18 March 2008.

Around 125,000 Tamils are estimated to be living in France. Of them, around 50,000 are Eezham Tamils (Sri Lankan Tamils).

- "Swiss Tamils look to preserve their culture". swissinfo. 18 February 2006.

An estimated 35,000 Tamils now live in Switzerland.

- "SPEECH BY MR. S RAJARATNAM, SENIOR MINISTER (PRIME MINISTER'S OFFICE), ON THE OCCASION OF THE 75TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF THE SINGAPORE CEYLON TAMILS' ASSOCIATION AT THE OBEROI IMPERIAL HOTEL ON SUNDAY, 10 FEBRUARY 1985 AT 7.30 PM" (PDF). 10 February 1985.

- Sivasupramaniam, V. "History of the Tamil Diaspora". International Conferences on Skanda-Murukan.

- "The Sri Lankan Tamil Diaspora after the LTTE". 23 February 2010.

- Rajakrishnan 1993, pp. 541–557.

- Raman, B. (14 July 2000). "Sri Lanka: The dilemma". Business Line.

It is estimated that there are about 10,000 Sri Lankan Tamils in Norway – 6,000 of them Norwegian citizens, many of whom migrated to Norway in the 1960s and the 1970s to work on its fishing fleet; and 4,000 post-1983 political refugees.

- Mortensen 2004, p. 110.

- Perera, Yohan. "22,254 Tamil Buddhists in SL". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "22,254 Tamil Buddhists in SL". www.dailymirror.lk. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Kirk, R. L. (1976). "The legend of Prince Vijaya — a study of Sinhalese origins". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 45: 91–99. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330450112.

- Krishnan, Shankara (1999). Postcolonial Insecurities: India, Sri Lanka, and the Question of Nationhood. University of Minnesota Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-8166-3330-2.

- "Q&A: Post-war Sri Lanka". BBC News. 20 September 2013.

- "'Tamils still being raped and tortured' in Sri Lanka". BBC News. 9 November 2013.

- "'Tamils fear prison and torture in Sri Lanka 13 years after civil war ended". The Guardian. 26 March 2022.

- Darusman, Marzuki; Sooka, Yasmin; Ratner, Steven R. (31 March 2011). Report of the Secretary-General's Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka (PDF). United Nations. p. 41.

- "Sri Lanka president says war missing are dead". BBC News. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "ASA 37/011/2012 Sri Lanka: Continuing Impunity, Arbitrary Detentions, Torture and Enforced Disappearances". Amnesty International. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Kaiser, Katrina (30 July 2012). "Press Freedom Under Attack in Sri Lanka: Website Office Raids and Online Content Regulation". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Jayasinghe, Amal (2 November 2012). "Amnesty accuses Sri Lanka of targeting judges". Agence France-Presse.

- "Why I'm Not 'Sri Lankan'".

- "TamilNet".

- Colombo Telegraph - Vaddukoddai Resolution: More Relevant Now Than Ever Before, https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/vaddukoddai-resolution-more-relevant-now-than-ever-before/

- "Parliamentary Election - 1977" (PDF). Department of Elections Sri Lanka. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Adrian Wijemanne, War and Peace in Post-colonial Ceylon, 1948-1991, 1996, p32 https://www.google.com/books/edition/War_and_Peace_in_Post_colonial_Ceylon_19/9EiToLETF5UC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA32&printsec=frontcover

- International Crisis Group - The Sri Lankan Tamil Diaspora after the LTTE, p13-14 https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/113104/186_the_sri_lankan_tamil_diaspora.pdf

- "Tamil National Alliance -A Sinking Ship". 3 September 2018.

- "Eelam Tamil flag hoisted in Valvettithurai | Tamil Guardian".

- "Tamils across London hoist Tamil Eelam flags in build-up to Maaveerar Naal | Tamil Guardian".

- Pande, Amba (5 December 2017). Women in the Indian Diaspora: Historical Narratives and Contemporary Challenges. Springer. p. 106. ISBN 978-981-10-5951-3.

- Indrapala, Karthigesu (1969). "Early Tamil Settlements in Ceylon". The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. Sri Lanka: Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka. 13: 43–63. JSTOR 43483465.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (8 March 2002). "Aryan or Dravidian or Neither? – A Study of Recent Attempts to Decipher the Indus Script (1995–2000)". Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 8 (1). ISSN 1084-7561. Archived from the original on 23 July 2007.

- Wenzlhuemer 2008, pp. 19–20.

- de Silva 2005, p. 129.

- "Vedda". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. London: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- Indrapala 2007, pp. 53–54.

- Schalk, Peter (2002). Buddhism Among Tamils in Pre-colonial Tamilakam and Ilam: Prologue. The Pre-Pallava and the Pallava Period. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Vol. 19–20. Uppsala University. pp. 100–220. ISBN 978-91-554-5357-2.

- "Reading the past in a more inclusive way - Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne". Frontline (2006). 26 January 2006.

- Seneviratne, Sudharshan (1984). Social base of early Buddhism in south east India and Sri Lanka.

- Karunaratne, Priyantha (2010). Secondary state formation during the early iron age on the island of Sri Lanka : the evolution of a periphery.

- Robin Conningham - Anuradhapura - The British-Sri Lankan Excavations at Anuradhapura Salgaha Watta Volumes 1 and 2 (1999/2006)

- Sudharshan Seneviratne (1989) - Pre-State Chieftains And Servants of the State: A Case Study of Parumaka -http://dlib.pdn.ac.lk/handle/123456789/2078

- Indrapala 2007, p. 91.

- Indian Journal of History of Science, 45.3 (2010) 369-394, Adichanallur: A prehistoric mining site https://insa.nic.in/writereaddata/UpLoadedFiles/IJHS/Vol45_3_3_BSasisekara.pdf

- Frontline, Reading the past in a more inclusive way - Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne. (2006) https://frontline.thehindu.com/other/article30208096.ece

- Indrapala 2007, p. 324.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (24 June 2010). "An epigraphic perspective on the antiquity of Tamil". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010.

- Mahadevan 2003, p. 48.

- "The Consecrating of Vijaya". Mahavamsa. 8 October 2011.

- Indrapala 2007, p. 157.

- Mahadevan 2000, pp. 152–154.

- Bopearachchi 2004, pp. 546–549.

- Senanayake, A.M.P. (2017). "A STUDY ON SOCIAL IDENTITY BASED ON THE BRAHMI INSCRIPTIONS OF THE EARLY HISTORIC PERIOD IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCE, SRI LANKA" (PDF). Social Affairs: A Journal for the Social Sciences. 1 (6): 38.

- de Silva 1987, pp. 30–32.

- Mendis 1957, pp. 24–25.

- Nadarajan 1999, p. 40.

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (1994). "Tamils and the meaning of history". Contemporary South Asia. 3 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1080/09584939408719724.

- Schalk, Peter (2002). "Buddhism Among Tamils in Pre-colonial Tamilakam and Ilam: Prologue. The Pre-Pallava and the Pallava period". Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Uppsala University. 19–20: 159, 503.

The Tamil stone inscription Konesar Kalvettu details King Kulakottan's involvement in the restoration of Koneswaram temple in 438 A.D. (Pillay, K., Pillay, K. (1963). South India and Ceylon)

- Arumugam, S. (1980). The Lord of Thiruketheeswaram, an ancient Hindu sthalam of hoary antiquity in Sri Lanka. Colombo.

Kulakottan also paid special attention to agricultural practice and economic development, the effects of which made the Vanni region to flourish; temples were cared for and regular worship instituted at these

- Ismail, Marina (1995). Early settlements in northern Sri lanka.

In the sixth century AD there was a coastal route by boat from the Jaffna peninsula in the north, southwards to Trincomalee, especially to the religious centre of Koneswaram, and further onwards to Batticaloa and the religious centre of Tirukovil, along the eastern coast. Along this route there were a few small trading settlements such as Mullativu on the north coast...

- Singhal, Damodhar P. (1969). India and world civilization. Vol. 2. University of Michigan Press. OCLC 54202.

- Codrington, Humphrey William (May 1995). Short History of Ceylon. p. 36. ISBN 9788120609464.

- Maity, Sachindra Kumar (1982). Masterpieces of Pallava Art. p. 4.

- Spencer, George W. "The politics of plunder: The Cholas in eleventh century Ceylon". The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 35 (3): 408.

- Indrapala 2007, pp. 214–215.

- The 1681 CE map by Robert Knox demarcates the then existing boundaries of the Tamil country. In 1692 CE, Dutch artist Wilhelm Broedelet crafted an engraving of the map: Coylat Wannees Land, where the Malabars live – An Historical Relation of the Island of Ceylon, Atlas of Mutual Heritage, Netherlands.

- de Silva 1987, p. 46.

- de Silva 1987, p. 48.

- de Silva 1987, p. 75.

- Mendis 1957, pp. 30–31.

- Smith 1958, p. 224.

- Rice, Benjamin Lewis (10 May 2012). Epigraphia Carnatica, Volume 10, Part 1. p. 32. ISBN 9781231192177.

- Pillay, K. (1963). South India and Ceylon. University of Madras. OCLC 250247191.

- Balachandran, P.K. (10 March 2010). "Chola era temple excavated off Jaffna". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- de Silva 1987, p. 76.

- de Silva 1987, pp. 100–102.

- de Silva 1987, pp. 102–104.

- de Silva 1987, p. 104.

- Kaplan, Robert D. (2010). Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power'. ISBN 9780679604051.

- Pires, Tomé; Rodrigues, Francisco; Cortesão, Armando (2005). The Suma oriental of Tome Pires : an account of the east, from the red sea to China, written in Malacca and India in 1512–1515; and, The book of Francisco Rodrigues: pilot-major of the armada that discovered Banda and the Moluccas: rutter of a voyage in the red sea, nautical rules, almanack and, maps, written and drawn in the east before 1515. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 85. ISBN 978-81-206-0535-0.

- Indrapala 2007, p. 210.

- Nampota. Colombo: M. D. Gunasena & Co. 1955. pp. 5–6.

- Knox 1681, p. 166.

- de Silva 1987, p. 121.

- Spencer 1990, p. 23.

- Indrapala 2007, p. 275.

- "Population by ethnic group, census years" (PDF). Statistical Abstract 2011. Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2012.

- "Estimated mid year population by ethnic group, 1980–1989" (PDF). Statistical Abstract 2011. Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2012.

- Orjuela, Camilla (2012). "5: Diaspora Identities and Homeland Politics". In Terrence Lyons; Peter G. Mandaville (eds.). Politics from Afar: Transnational Diasporas and Networks. C. Hurst & Co. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-84904-185-0.

- "The Sri Lankan Tamil Diaspora after the LTTE: Asia Report N°186". International Crisis Group. 23 February 2010. p. 2. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010.

- Mohan, Vasundhara (1987). Identity Crisis of Sri Lankan Muslims. Delhi: Mittal Publications. pp. 9–14, 27–30, 67–74, 113–118.

- Ross Brann, "The Moors?"

- "Analysis: Tamil-Muslim divide". BBC News World Edition. 27 June 2002. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Zemzem, Akbar (1970). The Life and Times of Marhoom Wappichi Marikar (booklet). Colombo.

- de Silva 1987, pp. 3–5.

- de Silva 1987, p. 9.

- Department of Census and Statistics of Sri Lanka. "Population by Ethnicity according to District" (PDF). statistics.gov.lk. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

- de Silva 1987, p. 177.

- de Silva 1987, p. 181.

- Suryanarayan, V. (4 August 2001). "In search of a new identity". Frontline. 18 (16). Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- de Silva 1987, p. 262.

- Indrapala 2007, p. 230.

- Sivathamby 1995, pp. 2–4.

- Subramaniam 2006, pp. 1–13.

- McGilvray, D. Mukkuvar Vannimai: Tamil Caste and Matriclan Ideology in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka, pp. 34–97

- Sivathamby 1995, pp. 7–9.

- McGilvray, Dennis B. (1982). Caste Ideology and Interaction. Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780521241458.

- Ruwanpura, Kanchana N. (2006). Matrilineal Communities, Patriarchal Realities: A Feminist Nirvana Uncovered. University of Michigan Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-472-06977-4.

- Yalman 1967, pp. 282–335.

- Sivathamby 1995, pp. 5–6.

- Seligmann, C.G.; Gabriel, C.; Seligmann, B.Z. (1911). The Veddas. pp. 331–335.

- Thambiah 2001, p. 2.

- Sivathamby 1995, pp. 4–12.

- Fernando, A. Denis N. (1987). "Pennsular Jaffna From Ancient to Medieval Times: Its Significant Historical and Settlement Aspects". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka. 32: 63–90. JSTOR 23731055.

- Gerharz, Eva (3 April 2014). The Politics of Reconstruction and Development in Sri Lanka: Transnational Commitments to Social Change. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-69279-9.

- Gunasingam 1999, p. 62.

- Pfister, Raymond (1995). Soixante ans de pentecôtisme en Alsace (1930–1990): une approche socio-historique. P. Lang. p. 165. ISBN 978-3-631-48620-7.

- Pranāndu, Mihindukalasūrya Ār Pī Susantā (2005), Rituals, folk beliefs, and magical arts of Sri Lanka, Susan International, p. 459, ISBN 9789559631835, retrieved 11 March 2018

- Nayagam, Xavier S. Thani (1959), Tamil Culture, Academy of Tamil Culture, retrieved 11 March 2018

- Thambiah 2001, p. 12.

- Fernando v. Proctor el al, 3 Sri Lanka 924 (District Court, Chilaw 27 October 1909).

- Gair 1998, p. 171.

- Bonta, Steven (June 2008). "Negombo Fishermen's Tamil (NFT): A Sinhala Influenced Dialect from a Bilingual Sri Lankan Community". International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. 37.

- Foell, Jens (2007). "Participation, Patrons and the Village: The case of Puttalam District". University of Sussex. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

One of the most interesting processes in Mampuri is the one of Sinhalisation. Whilst most of the Sinhala fishermen used to speak Tamil and/or still do so, there is a trend towards the use of Sinhala, manifesting itself in most children being educated in Sinhala and the increased use of Sinhala in church. Even some of the long-established Tamils, despite having been one of the most powerful local groups in the past, due to their long local history as well as caste status, have adapted to this trend. The process reflects the political domination of Sinhala people in the Government controlled areas of the country.

- Peebles, Patrick (2015). Historical Dictionary of Sri Lanka. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 55. ISBN 9781442255852.

- Goonetilleke, Susantha (1 May 1980). "Sinhalisation: Migration or Cultural Colonization?". Lanka Guardian: 18–29.

- Corea, Henry (3 October 1960). "The Maravar Suitor". Sunday Observer (Sri Lanka). Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- Rajeswaran, S.T.B. (2012). Geographical Aspects of the Northern Province, Sri Lanka. Governor's Office. p. 69.

- Bonta, Steven (2010). "Negombo Fishermen's Tamil: A Case of Indo-Aryan Contact-Induced Change in a Dravidian Dialect". Anthropological Linguistics. 52 (3/4): 310–343. doi:10.1353/anl.2010.0021. JSTOR 41330804. S2CID 144089805.

- "How a unique Tamil dialect survived among a fishing community in Sri Lanka".

- Kularatnam, K. (April 1966). "Tamil Place Names in Ceylon outside the Northern and Eastern Provinces". Proceedings of the First International Conference Seminar of Tamil Studies, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia vol.1. International Association of Tamil Research. pp. 486–493.

- Kshatriya, GK (December 1995). "Genetic affinities of Sri Lankan populations". Human Biology. 67 (6): 843–66. PMID 8543296.

- "Molecular Anthropology: Population and Forensic Genetic Applications" (PDF).

- Kirk, R.L. (1976), The Legend of Prince Vijaya — a study of Sinhalese origins. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol., 45: 91-99. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330450112

- "A Hindu Gentleman of North Ceylon". Wesleyan Juvenile Offering. XVI: 72. July 1859. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- "Sri Lanka: Country study". The Library of Congress. 1988. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Hudson 1982, p. 29.

- Sivathamby 1995, pp. 34–89.

- "Overview: Pentecostalism in Asia". The pew forum. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- PhD Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Jaffna: Thillimalar Ragupathy. p. 217.

- Harrison, Frances (8 April 2008). "Tamil Tigers appeal over shrine". BBC News.

- Manogaran 2000, p. 46.

- Kuiper, L.B.J (March 1964). "Note on Old Tamil and Jaffna Tamil". Indo-Iranian Journal. 6 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1163/000000062791616020. JSTOR 24646759. S2CID 161679797.

- "Census of Population and Housing 2011". www.statistics.gov.lk. Department of Census and Statistics. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- Subramaniam 2006, p. 10.

- Zvlebil, Kamil (June 1966). "Some features of Ceylon Tamil". Indo-Iranian Journal. 9 (2): 113–138. doi:10.1007/BF00963656. S2CID 161144239.

- Swamy, B.G.L. (1975). "The Date of Tolksppiyam-a Retrospect". Annals of Oriental Research. Silver. Jubilee Volume: 292–317.

- Manogaran, Chelvadurai (1987). Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka. University of Hawaii Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780824811167.

- Pfaffenberger, Bryan (1977). Pilgrimage and Traditional Authority in Tamil Sri Lanka. University of California, Berkeley. p. 15.

- Schiffman, Harold (30 October 1996). "Language Shift in the Tamil Communities of Malaysia and Singapore: the Paradox of Egalitarian Language Policy". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- Indrapala 2007, p. 45.

- Indrapala 2007, p. 389.

- Ragupathy, P. Tamil Social Formation in Sri Lanka: A Historical Outline'. p. 1.

- Gunasingam 1999, pp. 64–65.

- Gunasingam 1999, p. 68.

- Gunasingam 1999, pp. 73–109.

- Pfaffenberg 1994, p. 110.

- Ambihaipahar 1998, p. 29.

- Sivathamby, K. (2005). "50 years of Sri Lankan Tamil literature". Tamil Circle. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- Nadarajan 1999, pp. 80–84.

- Knuth, Rebecca (2006). Destroying a Symbol: Checkered History of Sri Lanka's Jaffna Public Library (PDF). University of Hawaii.

- Ramakrishnan, Rohini (20 July 2003). "From the land of the Yaal Padi". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013.

- Pujangga 1997, p. 75.

- Pujangga 1997, p. 72.

- Pujangga 1997, p. 73.

- Peebles, Patrick (February 1990). "Colonization and Ethnic Conflict in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka". Journal of Asian Studies. 49 (1): 30–55. doi:10.2307/2058432. JSTOR 2058432.

- Doucet, Lyse (13 November 2012). "UN 'failed Sri Lanka civilians', says internal probe". BBC News.

- Peachey, Paul (2 September 2013). "Sri Lanka snubs UN as it bids for more trade links with the UK". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022.

- "S Lanka civilian toll 'appalling'". BBC News. 13 February 2008.

Sri Lanka's government is one of the world's worst perpetrators of enforced disappearances, US-based pressure group Human Rights Watch (HRW) says. An HRW report accuses security forces and pro-government militias of abducting and "disappearing" hundreds of people—mostly Tamils—since 2006.

- Pathirana, Saroj (26 September 2006). "Fears grow over Tamil abductions". BBC News.

The image of the "white van" invokes memories of the "era of terror" in the late 1980s when death squads abducted and killed thousands of Sinhala youth in the south of the country. The Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) says the "white van culture" is now re-appearing in Colombo to threaten the Tamil community.

- Denyer, Simon (14 September 2006). ""Disappearances" on rise in Sri Lanka's dirty war". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

The National Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka has recorded 419 missing people in Jaffna since December 2005.

- Newman, Jesse (2003). "Narrating displacement:Oral histories of Sri Lankan women". Refugee Studies Centre – Working Papers. Oxford University (15): 3–60.

- Gunasingam 1999, p. 108.

- Gunasingam 1999, p. 201.

- The Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms http://countrystudies.us/sri-lanka/13.htm

- McConnell, D. (2008). "The Tamil people's right to self-determination". Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 21 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1080/09557570701828592. S2CID 154770852.

- Gunasingam 1999, p. 76.

- de Silva, K.M. (1995). History of Sri Lanka. Penguin Books.

- Gunasingam 1999, p. 5.

- Gunasingam 1999, p. 6.

- Wilson 2000, p. 79.

- Russell, Ross (1988). "Sri Lanka:Country study". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Roberts, Michael (November 2007). "Blunders in Tigerland: Papes muddles on suicide bombers". Heidelberg Papers on South Asian and Comparative Politics. University of Heidelberg. 32: 14.

- Russel, Ross (1988). "Tamil Alienation". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Jayasuriya, J.E. (1981). Education in the Third World: Some Reflections. Pune: ndian Institute of Education.

- Wilson 2000, pp. 101–110.

- Gunasingam 1999, p. 7.

- Kearney, R.N. (1985). "Ethnic Conflict and the Tamil Separatist Movement in Sri Lanka". Asian Survey. 25 (9): 898–917. doi:10.2307/2644418. JSTOR 2644418.

- Wilson 2000, p. 125.

- Knuth, Rebecca (2006). "Destroying a symbol" (PDF). International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- Russell, Ross (1988). "Tamil Militant Groups". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Shastri, A. (1990). "The Material Basis for Separatism: The Tamil Eelam Movement in Sri Lanka". The Journal of Asian Studies. 49 (1): 56–77. doi:10.2307/2058433. JSTOR 2058433.

- Kumaratunga, Chandrika (24 July 2004). "Speech by President Chandrika Kumaratunga at the 21st Anniversary of 'Black July', Presidential Secretariat, Colombo, July 23, 2004". SATP. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- Harrison, Frances (23 July 2003). "Twenty years on – riots that led to war". BBC News.

Indeed nobody really knows how many Tamils died in that one week in July 1983. Estimates vary from 400 to 3,000 dead.

- Marschall, Wolfgang (2003). "Social Change Among Sri Lankan Tamil Refugees in Switzerland". University of Bern. Archived from the original on 5 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- "2000 Human Rights Report: Sri Lanka". United States Department of State. 2000. Archived from the original on 7 June 2001. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- "The EU's relations with Sri Lanka – Overview". European Union. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 September 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- "Open letter to LTTE, SLMM and SL Police concerning recent politically motivated killings and abductions in Sri Lanka". Amnesty International. 2003. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "Amnesty International report for Sri Lanka 2007". Amnesty International. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- "Sri Lankan army and Tamil Tiger death tolls reveal grim cost of years of civil war". Financial Times. 23 May 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2009.

- Buncombe, Andrew (12 February 2010). "Up to 40,000 civilians 'died in Sri Lanka offensive'". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- Buerk, Roland (23 July 2008). "Sri Lankan families count cost of war". BBC News.

- "Sri Lankan introduces new 'anti-terror' legislation". BBC News. 2 August 2011.

- "Sri Lanka to release 107 rehabilitated LTTE cadres". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 8 September 2013. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013.

- Senewiratne, Brian (7 April 2012). "The Life of a Sri Lankan Tamil Bishop (and others) in Danger". Salem-News.com. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- "Lanka's main Tamil party TNA presses for Opposition status in Parliament". The Economic Times. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Sampanthan appointed Opposition Leader".

- "K. Sripavan sworn in as Chief Justice". Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Indrapala 2007, pp. 253–254.

- "Who is Ananda Krishnan?". The Sunday Times (Sri Lanka). 27 May 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2008.

- "#17 G. Gnanalingam". 2 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Chongkittavorn, Kavi (6 August 2007). "Asean's birth a pivotal point in history of Southeast Asia". The Nation (Thailand). Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2008.