Destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in 1885 by Fernando Villaamil for the Spanish Navy[1][2] as a defense against torpedo boats, and by the time of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, these "torpedo boat destroyers" (TBDs) were "large, swift, and powerfully armed torpedo boats designed to destroy other torpedo boats".[3] Although the term "destroyer" had been used interchangeably with "TBD" and "torpedo boat destroyer" by navies since 1892, the term "torpedo boat destroyer" had been generally shortened to simply "destroyer" by nearly all navies by the First World War.[4]

Before World War II, destroyers were light vessels with little endurance for unattended ocean operations; typically a number of destroyers and a single destroyer tender operated together. After the war, the advent of the guided missile allowed destroyers to take on the surface combatant roles previously filled by battleships and cruisers. This resulted in larger and more powerful guided missile destroyers more capable of independent operation.

At the start of the 21st century, destroyers are the global standard for surface combatant ships, with only two nations (United States and Russia) officially operating the heavier class cruisers, with no battleships or true battlecruisers remaining.[note 1] Modern guided missile destroyers are equivalent in tonnage but vastly superior in firepower to cruisers of the World War II era, and are capable of carrying nuclear-tipped cruise missiles. At 510 feet (160 m) long, a displacement of 9,200 tons, and with an armament of more than 90 missiles,[5] guided missile destroyers such as the Arleigh Burke class are actually larger and more heavily armed than most previous ships classified as guided missile cruisers. The Chinese Type 055 destroyer has been described as a cruiser in some US Navy reports due to its size and armament.[6]

Some NATO navies, such as the Canadian, French, Spanish, Dutch and German, use the term "frigate" for their destroyers, which leads to some confusion.

After the Second World War, destroyers grew in size. The American Allen M. Sumner-class destroyers had a displacement of 2,200 tons, while the Arleigh Burke class has a displacement of up to 9,600 tons, thus growing in size almost 340%.

Origins

.jpg.webp)

The emergence and development of the destroyer was related to the invention of the self-propelled torpedo in the 1860s. A navy now had the potential to destroy a superior enemy battle fleet using steam launches to fire torpedoes. Cheap, fast boats armed with torpedoes called torpedo boats were built and became a threat to large capital ships near enemy coasts. The first seagoing vessel designed to launch the self-propelled Whitehead torpedo was the 33-ton HMS Lightning in 1876.[7] She was armed with two drop collars to launch these weapons, these were replaced in 1879 by a single torpedo tube in the bow. By the 1880s, the type had evolved into small ships of 50–100 tons, fast enough to evade enemy picket boats.

At first, the threat of a torpedo boat attack to a battle fleet was considered to exist only when at anchor; but as faster and longer-range torpedo boats and torpedoes were developed, the threat extended to cruising at sea. In response to this new threat, more heavily gunned picket boats called "catchers" were built which were used to escort the battle fleet at sea. They needed significant seaworthiness and endurance to operate with the battle fleet, and as they inherently became larger, they became officially designated "torpedo boat destroyers", and by the First World War were largely known as "destroyers" in English. The anti-torpedo boat origin of this type of ship is retained in its name in other languages, including French (contre-torpilleur), Italian (cacciatorpediniere), Portuguese (contratorpedeiro), Czech (torpédoborec), Greek (antitorpiliko, αντιτορπιλικό), Dutch (torpedobootjager) and, up until the Second World War, Polish (kontrtorpedowiec, now obsolete).[8]

Once destroyers became more than just catchers guarding an anchorage, it was realized that they were also ideal to take over the offensive role of torpedo boats themselves, so they were also fitted with torpedo tubes in addition to their anti torpedo-boat guns. At that time, and even into World War I, the only function of destroyers was to protect their own battle fleet from enemy torpedo attacks and to make such attacks on the battleships of the enemy. The task of escorting merchant convoys was still in the future.

Early designs

An important development came with the construction of HMS Swift in 1884, later redesignated TB 81.[9] This was a large (137 ton) torpedo boat with four 47 mm quick-firing guns and three torpedo tubes. At 23.75 knots (43.99 km/h; 27.33 mph), while still not fast enough to engage enemy torpedo boats reliably, the ship at least had the armament to deal with them.

Another forerunner of the torpedo boat destroyer was the Japanese torpedo boat[10] Kotaka (Falcon), built in 1885.[11] Designed to Japanese specifications and ordered from the Isle of Dogs, London Yarrow shipyard in 1885, she was transported in parts to Japan, where she was assembled and launched in 1887. The 165-foot (50 m) long vessel was armed with four 1-pounder (37 mm) quick-firing guns and six torpedo tubes, reached 19 knots (35 km/h), and at 203 tons, was the largest torpedo boat built to date. In her trials in 1889, Kotaka demonstrated that she could exceed the role of coastal defense, and was capable of accompanying larger warships on the high seas. The Yarrow shipyards, builder of the parts for Kotaka, "considered Japan to have effectively invented the destroyer".[12]

The German aviso Greif, launched in 1886, was designed as a "torpedojäger" (torpedo hunter), intended to screen the fleet against attacks by torpedo boats. The ship was significantly larger than torpedo boats of the period, displacing some 2,266 t (2,230 long tons), with an armament of 10.5 cm (4.1 in) guns and 3.7 cm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannon.[13]

Torpedo gunboat

The first vessel designed for the explicit purpose of hunting and destroying torpedo boats was the torpedo gunboat. Essentially very small cruisers, torpedo gunboats were equipped with torpedo tubes and an adequate gun armament, intended for hunting down smaller enemy boats. By the end of the 1890s torpedo gunboats were made obsolete by their more successful contemporaries, the torpedo boat destroyers, which were much faster.

The first example of this was HMS Rattlesnake, designed by Nathaniel Barnaby in 1885, and commissioned in response to the Russian War scare.[14] The gunboat was armed with torpedoes and designed for hunting and destroying smaller torpedo boats. Exactly 200 feet (61 m) long and 23 feet (7.0 m) in beam, she displaced 550 tons. Built of steel, Rattlesnake was un-armoured with the exception of a 3⁄4-inch protective deck. She was armed with a single 4-inch/25-pounder breech-loading gun, six 3-pounder QF guns and four 14-inch (360 mm) torpedo tubes, arranged with two fixed tubes at the bow and a set of torpedo dropping carriages on either side. Four torpedo reloads were carried.[14]

A number of torpedo gunboat classes followed, including the Grasshopper class, the Sharpshooter class, the Alarm class and the Dryad class – all built for the Royal Navy during the 1880s and the 1890s. In the 1880s, the Chilean Navy ordered the construction of two Almirante Lynch class torpedo gunboats from the British shipyard Laird Brothers, which specialized in the construction of this type of vessel. The novelty is that one of these Almirante Lynch class torpedo boats managed to sink the ironclad Blanco Encalada with a self-propelled torpedoes in the Battle of Caldera Bay in 1891, thus surpassing its main function of hunting torpedo boats.

Fernando Villaamil, second officer of the Ministry of the Navy of Spain, designed his own torpedo gunboat to combat the threat from the torpedo boat.[15] He asked several British shipyards to submit proposals capable of fulfilling these specifications. In 1885 the Spanish Navy chose the design submitted by the shipyard of James and George Thomson of Clydebank. Destructor (Destroyer in Spanish) was laid down at the end of the year, launched in 1886, and commissioned in 1887. Some authors considered her as the first destroyer ever built.[16][17]

.svg.png.webp)

She displaced 348 tons, and was the first warship[18] equipped with twin triple-expansion engines generating 3,784 ihp (2,822 kW), for a maximum speed of 22.6 knots (41.9 km/h),[19] which made her one of the faster ships in the world in 1888.[20] She was armed with one 90 mm (3.5 in) Spanish-designed Hontoria breech-loading gun,[1] four 57 mm (2.2 in) (6-pounder) Nordenfelt guns, two 37 mm (1.5 in) (3-pdr) Hotchkiss cannons and two 15-inch (38 cm) Schwartzkopff torpedo tubes.[19] The ship carried three torpedoes per tube.[1] She carried a crew of 60.[19]

In terms of gunnery, speed and dimensions, the specialised design to chase torpedo boats and her high seas capabilities, Destructor was an important precursor to the torpedo boat destroyer.[21][1]

Development of modern destroyers

.jpg.webp)

The first classes of ships to bear the formal designation "torpedo boat destroyer" (TBD) were the Daring class of two ships and Havock class of two ships of the Royal Navy.

Early torpedo gunboat designs lacked the range and speed to keep up with the fleet they were supposed to protect. In 1892, the Third Sea Lord, Rear Admiral John "Jacky" Fisher ordered the development of a new type of ships equipped with the then novel water-tube boilers and quick-firing small calibre guns. Six ships to the specifications circulated by the Admiralty were ordered initially, comprising three different designs each produced by a different shipbuilder: HMS Daring and HMS Decoy from John I. Thornycroft & Company, HMS Havock and HMS Hornet from Yarrows, and HMS Ferret and HMS Lynx from Laird, Son & Company.[22]

These torpedo boat destroyers all featured a turtleback (i.e. rounded) forecastle that was characteristic of early British TBDs. HMS Daring and HMS Decoy were both built by Thornycroft, displaced 260 tons (287.8 tons full load) and were 185 feet in length. They were armed with one 12-pounder gun and three 6-pounder guns, with one fixed 18-in torpedo tube in the bow plus two more torpedo tubes on a revolving mount abaft the two funnels. Later the bow torpedo tube was removed and two more 6-pounder guns added instead. They produced 4,200 hp from a pair of Thornycroft water-tube boilers, giving them a top speed of 27 knots, giving the range and speed to travel effectively with a battle fleet. In common with subsequent early Thornycroft boats, they had sloping sterns and double rudders.[23]

The French navy, an extensive user of torpedo boats, built its first torpedo boat destroyer in 1899, with the Durandal-class 'torpilleur d'escadre'. The United States commissioned its first torpedo boat destroyer, USS Bainbridge, Destroyer No. 1, in 1902 and by 1906 there were 16 destroyers in service with the US Navy.[24]

Subsequent improvements

Torpedo boat destroyer designs continued to evolve around the turn of the 20th century in several key ways. The first was the introduction of the steam turbine. The spectacular unauthorized demonstration of the turbine-powered Turbinia at the 1897 Spithead Navy Review, which, significantly, was of torpedo boat size, prompted the Royal Navy to order a prototype turbine powered destroyer, HMS Viper of 1899. This was the first turbine warship of any kind and achieved a remarkable 34 knots (63 km/h; 39 mph) on sea trials. By 1910 the turbine had been widely adopted by all navies for their faster ships.[7]

The second development was the replacement of the torpedo-boat-style turtleback foredeck by a raised forecastle for the new River-class destroyers built in 1903, which provided better sea-keeping as well as more space below deck.

The first warship to use only fuel oil propulsion was the Royal Navy's torpedo boat destroyer HMS Spiteful, after experiments in 1904, although the obsolescence of coal as a fuel in British warships was delayed by its availability.[25][26] Other navies also adopted oil, for instance the USN with the Paulding class of 1909. In spite of all this variety, destroyers adopted a largely similar pattern. The hull was long and narrow, with a relatively shallow draft. The bow was either raised in a forecastle or covered under a turtleback; underneath this were the crew spaces, extending 1⁄4 to 1⁄3 the way along the hull. Aft of the crew spaces was as much engine space as the technology of the time would allow: several boilers and engines or turbines. Above deck, one or more quick-firing guns were mounted in the bows, in front of the bridge; several more were mounted amidships and astern. Two tube mountings (later on, multiple mountings) were generally found amidships.

Between 1892 and 1914 destroyers became markedly larger: initially 275 tons with a length of 165 feet (50 m) for the Royal Navy's first Havock class of torpedo boat destroyers,[27] up to the First World War with 300-foot (91 m) long destroyers displacing 1,000 tons was not unusual. However, construction remained focused on putting the biggest possible engines into a small hull, resulting in a somewhat flimsy construction. Often hulls were built of high-tensile steel[7] only 1⁄8 in (3.2 mm) thick.

By 1910 the steam-driven displacement (that is, not hydroplaning) torpedo boat had become redundant as a separate type. Germany nevertheless continued to build such boats until the end of World War I, although these were effectively small coastal destroyers. In fact Germany never distinguished between the two types, giving them pennant numbers in the same series and never giving names to destroyers. Ultimately the term torpedo boat came to be attached to a quite different vessel – the very fast hydroplaning motor driven MTB.

Early use and World War I

Navies originally built torpedo boat destroyers to protect against torpedo boats, but admirals soon appreciated the flexibility of the fast, multi-purpose vessels that resulted. Vice-Admiral Sir Baldwin Walker laid down destroyer duties for the Royal Navy:[28]

- screening the advance of a fleet when hostile torpedo craft are about

- searching a hostile coast along which a fleet might pass

- watching an enemy's port for the purpose of harassing his torpedo craft and preventing their return

- attacking an enemy fleet

Early destroyers were extremely cramped places to live, being "without a doubt magnificent fighting vessels... but unable to stand bad weather".[29] During the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, the commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy torpedo boat destroyer Akatsuki[30][31][32] described "being in command of a destroyer for a long period, especially in wartime... is not very good for the health". Stating that he had originally been strong and healthy, he continued, "life on a destroyer in winter, with bad food, no comforts, would sap the powers of the strongest men in the long run. A destroyer is always more uncomfortable than the others, and rain, snow, and sea-water combine to make them damp; in fact, in bad weather there is not a dry spot where one can rest for a moment."[33]

The Japanese destroyer-commander finished with, "Yesterday I looked at myself in a mirror for a long time; I was disagreeably surprised to see my face thin, full of wrinkles, and as old as though I were fifty. My clothes (uniform) cover nothing but a skeleton, and my bones are full of rheumatism."[33]

In 1898, the US Navy officially classified USS Porter, a 175-foot (53 m) long all steel vessel displacing 165 tons, as a torpedo boat. However, her commander, LT. John C. Fremont, described her as "...a compact mass of machinery not meant to keep the sea nor to live in... as five sevenths of the ship are taken up by machinery and fuel, whilst the remaining two sevenths, fore and aft, are the crew's quarters; officers forward and the men placed aft. And even in those spaces are placed anchor engines, steering engines, steam pipes, etc. rendering them unbearably hot in tropical regions."[34]

Early combat

_IWM_SP_001136.jpg.webp)

The torpedo boat destroyer's first major use in combat came during the Japanese surprise attack on the Russian fleet anchored in Port Arthur at the opening of the Russo-Japanese War on 8 February 1904.

Three destroyer divisions attacked the Russian fleet in port, firing a total of 18 torpedoes. However, only two Russian battleships, Tsesarevich and Retvizan, and a protected cruiser, Pallada, were seriously damaged due to the proper deployment of torpedo nets. Tsesarevich, the Russian flagship, had her nets deployed, with at least four enemy torpedoes "hung up" in them,[35] and other warships were similarly saved from further damage by their nets.[36]

While capital ship engagements were scarce in World War I, destroyer units engaged almost continually in raiding and patrol actions. The first shot of the war at sea was fired on 5 August 1914 by HMS Lance, one of the 3rd Destroyer Flotilla, in an engagement with the German auxiliary minelayer Königin Luise.[37]

Destroyers were involved in the skirmishes that prompted the Battle of Heligoland Bight, and filled a range of roles in the Battle of Gallipoli, acting as troop transports and as fire-support vessels, as well as their fleet-screening role. Over 80 British destroyers and 60 German torpedo-boats took part in the Battle of Jutland, which involved pitched small-boat actions between the main fleets, and several foolhardy attacks by unsupported destroyers on capital ships. Jutland also concluded with a messy night action between the German High Seas Fleet and part of the British destroyer screen.

The threat evolved by World War I with the development of the submarine, or U-boat. The submarine had the potential to hide from gunfire and close underwater to fire torpedoes. Early-war destroyers had the speed and armament to intercept submarines before they submerged, either by gunfire or by ramming. Destroyers also had a shallow enough draft that torpedoes would find it difficult to hit them.

.jpg.webp)

The desire to attack submarines underwater led to rapid destroyer evolution during the war. They were quickly equipped with strengthened bows for ramming, and depth charges and hydrophones for identifying submarine targets. The first submarine casualty credited to a destroyer was the German U-19, rammed by HMS Badger on 29 October 1914. While U-19 was only damaged, the next month HMS Garry successfully sank U-18. The first depth-charge sinking was on 4 December 1916, when UC-19[38] was sunk by HMS Llewellyn.

The submarine threat meant that many destroyers spent their time on anti-submarine patrol. Once Germany adopted unrestricted submarine warfare in January 1917, destroyers were called on to escort merchant convoys. US Navy destroyers were among the first American units to be dispatched upon the American entry to the war, and a squadron of Japanese destroyers even joined Allied patrols in the Mediterranean. Patrol duty was far from safe; of the 67 British destroyers lost in the war, collisions accounted for 18, while 12 were wrecked.

At the end of the war, the state-of-the-art was represented by the British W class.

1918–1945

The trend during World War I had been towards larger destroyers with heavier armaments. A number of opportunities to fire at capital ships had been missed during the War, because destroyers had expended all their torpedoes in an initial salvo. The British V and W classes of the late war had sought to address this by mounting six torpedo tubes in two triple mounts, instead of the four or two on earlier models. The 'V' and 'W's set the standard of destroyer building well into the 1920s.

The two Romanian destroyers Mărăști and Mărășești, on the other hand, had the greatest firepower of all destroyers in the world throughout the first half of the 1920s. This was largely due to the fact that, between their commissioning in 1920 and 1926, they retained the armament that they had while serving in the Italian Navy as scout cruisers (esploratori). When initially ordered by Romania in 1913, the Romanian specifications envisioned three 120 mm guns, a caliber which would eventually be adopted as the standard for future Italian destroyers. Armed with three 152 mm and four 76 mm guns after being completed as scout cruisers, the two warships were officially re-rated as destroyers by the Romanian Navy. The two Romanian warships were thus the destroyers with the greatest firepower in the world throughout much of the interwar period. As of 1939, when the Second World War started, their artillery, although changed, was still close to cruiser standards, amounting to nine heavy naval guns (five of 120 mm and four of 76 mm). In addition, they retained their two twin 457 mm torpedo tubes as well as two machine guns, plus the capacity to carry up to 50 mines.[39]

The next major innovation came with the Japanese Fubuki class or 'special type', designed in 1923 and delivered in 1928. The design was initially noted for its powerful armament of six five-inch (127 mm) guns and three triple torpedo mounts. The second batch of the class gave the guns high-angle turrets for anti-aircraft warfare, and the 24-inch (61 cm) oxygen-fueled 'Long Lance' Type 93 torpedo. The later Hatsuharu class of 1931 further improved the torpedo armament by storing its reload torpedoes close at hand in the superstructure, allowing reloading within 15 minutes.

Most other nations replied with similar larger ships. The US Porter class adopted twin five-inch (127 mm) guns, and the subsequent Mahan class and Gridley classes (the latter of 1934) increased the number of torpedo tubes to 12 and 16 respectively.

In the Mediterranean, the Italian Navy's building of very fast light cruisers of the Condottieri class prompted the French to produce exceptional destroyer designs. The French had long been keen on large destroyers, with their Chacal class of 1922 displacing over 2,000 tons and carrying 130 mm guns; a further three similar classes were produced around 1930. The Fantasque class of 1935 carried five 138 millimetres (5.4 in) guns and nine torpedo tubes, but could achieve speeds of 45 knots (83 km/h), which remains the record speed for a steamship and for any destroyer.[40] The Italians' own destroyers were almost as swift, most Italian designs of the 1930s being rated at over 38 knots (70 km/h), while carrying torpedoes and either four or six 120 mm guns.

Germany started to build destroyers again during the 1930s as part of Hitler's rearmament program. The Germans were also fond of large destroyers, but while the initial Type 1934 displaced over 3,000 tons, their armament was equal to smaller vessels. This changed from the Type 1936 onwards, which mounted heavy 150 millimetres (5.9 in) guns. German destroyers also used innovative high-pressure steam machinery: while this should have helped their efficiency, it more often resulted in mechanical problems.

Once German and Japanese rearmament became clear, the British and American navies consciously focused on building destroyers that were smaller but more numerous than those used by other nations. The British built a series of destroyers (the A class to I class) which were about 1,400 tons standard displacement, had four 4.7-inch (119 mm) guns and eight torpedo tubes; the American Benson class of 1938 similar in size, but carried five 5-inch (127 mm) guns and ten torpedo tubes. Realizing the need for heavier gun armament, the British built the Tribal class of 1936 (sometimes called Afridi after one of two lead ships). These ships displaced 1,850 tons and were armed with eight 4.7-inch (119 mm) guns in four twin turrets and four torpedo tubes. These were followed by the J-class and L-class destroyers, with six 4.7-inch (119 mm) guns in twin turrets and eight torpedo tubes.

Anti-submarine sensors included sonar (or ASDIC), although training in their use was indifferent. Anti-submarine weapons changed little, and ahead-throwing weapons, a need recognized in World War I, had made no progress.

Later combat

_at_sea%252C_circa_in_1945.jpg.webp)

During the 1920s and 1930s, destroyers were often deployed to areas of diplomatic tension or humanitarian disaster. British and American destroyers were common on the Chinese coast and rivers, even supplying landing parties to protect colonial interests.

By World War II the threat had evolved once again. Submarines were more effective, and aircraft had become important weapons of naval warfare; once again the early-war fleet destroyers were ill-equipped for combating these new targets. They were fitted with new light anti-aircraft guns, radar, and forward-launched ASW weapons, in addition to their existing dual-purpose guns, depth charges, and torpedoes. Increasing size allowed improved internal arrangement of propulsion machinery with compartmentation so ships were less likely to be sunk by a single hit.[7] In most cases torpedo and/or dual-purpose gun armament was reduced to accommodate new anti-air and anti-submarine weapons. By this time the destroyers had become large, multi-purpose vessels, expensive targets in their own right. As a result, casualties on destroyers were among the highest. In the US Navy, particularly in World War II, destroyers became known as tin cans due to their light armor compared to battleships and cruisers.

The need for large numbers of anti-submarine ships led to the introduction of smaller and cheaper specialized anti-submarine warships called corvettes and frigates by the Royal Navy and destroyer escorts by the USN. A similar programme was belatedly started by the Japanese (see Matsu-class destroyer). These ships had the size and displacement of the original torpedo boat destroyers that the contemporary destroyer had evolved from.

Post-World War II

Some conventional destroyers were completed in the late 1940s and 1950s which built on wartime experience. These vessels were significantly larger than wartime ships and had fully automatic main guns, unit machinery, radar, sonar, and antisubmarine weapons such as the Squid mortar. Examples include the British Daring-class, US Forrest Sherman-class, and the Soviet Kotlin-class destroyers.

Some World War II–vintage ships were modernized for anti-submarine warfare, and to extend their service lives, to avoid having to build (expensive) brand-new ships. Examples include the US FRAM I programme and the British Type 15 frigates converted from fleet destroyers.

The advent of surface-to-air missiles and surface-to-surface missiles, such as the Exocet, in the early 1960s changed naval warfare. Guided missile destroyers (DDG in the US Navy) were developed to carry these weapons and protect the fleet from air, submarine and surface threats. Examples include the Soviet Kashin class, the British County class, and the US Charles F. Adams class.

21st century destroyers tend to display features such as large, slab sides without complicated corners and crevices to keep the radar cross-section small, vertical launch systems to carry a large number of missiles at high readiness to fire and helicopter flight decks and hangars.

Operators

Argentine Navy Operates four Almirante Brown-class destroyers and a single modified Type 42 destroyer.

Argentine Navy Operates four Almirante Brown-class destroyers and a single modified Type 42 destroyer. Royal Australian Navy Operates three Hobart-class destroyers. They are the first Australian warships to use the Aegis Combat System and are based on Spain's Álvaro de Bazán-class frigates.

Royal Australian Navy Operates three Hobart-class destroyers. They are the first Australian warships to use the Aegis Combat System and are based on Spain's Álvaro de Bazán-class frigates.

_20190729.jpg.webp)

People's Liberation Army Navy Operates four Renhai-class destroyers,[41] two Luyang I-class destroyers, six Luyang II-class destroyers, more than 18[42] Luyang III-class destroyers and two Luzhou-class destroyers. China also operates two Luhu-class destroyers, one Luhai-class destroyer and 4 Sovremenny-class destroyers that are of older models. It is notable that the Renhai-class (Type 055) is considered to be a cruiser by NATO and the U.S. Department of Defense for its tonnage and capability matching that of the Ticonderoga-class cruiser.[43]

People's Liberation Army Navy Operates four Renhai-class destroyers,[41] two Luyang I-class destroyers, six Luyang II-class destroyers, more than 18[42] Luyang III-class destroyers and two Luzhou-class destroyers. China also operates two Luhu-class destroyers, one Luhai-class destroyer and 4 Sovremenny-class destroyers that are of older models. It is notable that the Renhai-class (Type 055) is considered to be a cruiser by NATO and the U.S. Department of Defense for its tonnage and capability matching that of the Ticonderoga-class cruiser.[43] Republic of China Navy (Taiwan) Operates four Kidd-class destroyers, purchased from the United States.

Republic of China Navy (Taiwan) Operates four Kidd-class destroyers, purchased from the United States. Egyptian Navy Operates a single FREMM multipurpose frigate purchased from France, and a single Z-class destroyer for training use.

Egyptian Navy Operates a single FREMM multipurpose frigate purchased from France, and a single Z-class destroyer for training use. French Navy Operates eight FREMM multipurpose frigates and two Horizon-class frigates. The French Navy does not use the term "destroyer" but rather "first-rate frigate" to these ship types, but they are marked with the NATO "D" hull code which places them in the destroyer type, as opposed to "F" for frigate.

French Navy Operates eight FREMM multipurpose frigates and two Horizon-class frigates. The French Navy does not use the term "destroyer" but rather "first-rate frigate" to these ship types, but they are marked with the NATO "D" hull code which places them in the destroyer type, as opposed to "F" for frigate. German Navy operates three Sachsen-class frigates and four Baden-Württemberg-class frigates. These ships are officially classified as frigates by Germany, but regarded as destroyers internationally due to size and capability.

German Navy operates three Sachsen-class frigates and four Baden-Württemberg-class frigates. These ships are officially classified as frigates by Germany, but regarded as destroyers internationally due to size and capability. Hellenic Navy HS Velos (D-16), a Fletcher-class destroyer, remains ceremonially in commission due to her historical significance.

Hellenic Navy HS Velos (D-16), a Fletcher-class destroyer, remains ceremonially in commission due to her historical significance.

_-_P15B_destroyer_of_Indian_Navy_during_sea_trials.jpg.webp)

Indian Navy Operates one Visakhapatnam-class destroyer, three Kolkata-class destroyers, three Delhi , and three Rajput-class destroyers.

Indian Navy Operates one Visakhapatnam-class destroyer, three Kolkata-class destroyers, three Delhi , and three Rajput-class destroyers. Islamic Republic of Iran Navy operates three Moudge-class frigates. These ships are classified as destroyers by Iran, but internationally regarded as light frigates.

Islamic Republic of Iran Navy operates three Moudge-class frigates. These ships are classified as destroyers by Iran, but internationally regarded as light frigates.

Italian Navy Operates two Durand de la Penne-class destroyers and two Orizzonte-class destroyers.

Italian Navy Operates two Durand de la Penne-class destroyers and two Orizzonte-class destroyers. Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Operates the Maya-class, Atago-class, and Kongō-class destroyers which all employ the Aegis combat system. Japan also operates two Hatakaze-class, four Akizuki-class, five Takanami-class, nine Murasame-class, eight Asagiri-class, and six Abukuma-class destroyers.

Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Operates the Maya-class, Atago-class, and Kongō-class destroyers which all employ the Aegis combat system. Japan also operates two Hatakaze-class, four Akizuki-class, five Takanami-class, nine Murasame-class, eight Asagiri-class, and six Abukuma-class destroyers. Republic of Korea Navy Operates several classes of destroyers including the Sejong the Great-class (KDX-III), the Chungmugong Yi Sun-shin-class (KDX-II) and Gwanggaeto the Great-class (KDX-I) destroyers. The KDX-III is equipped with the Aegis combat system, Goalkeeper CIWS, Hyunmoo cruise missile and the Hae Sung anti-ship missile.

Republic of Korea Navy Operates several classes of destroyers including the Sejong the Great-class (KDX-III), the Chungmugong Yi Sun-shin-class (KDX-II) and Gwanggaeto the Great-class (KDX-I) destroyers. The KDX-III is equipped with the Aegis combat system, Goalkeeper CIWS, Hyunmoo cruise missile and the Hae Sung anti-ship missile. Royal Moroccan Navy operates a single FREMM multipurpose frigate ordered from France.

Royal Moroccan Navy operates a single FREMM multipurpose frigate ordered from France. Royal Netherlands Navy operates four De Zeven Provinciën-class frigates. These ships are classified as frigates by The Netherlands, but regarded as destroyers internationally due to size and capability.

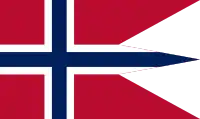

Royal Netherlands Navy operates four De Zeven Provinciën-class frigates. These ships are classified as frigates by The Netherlands, but regarded as destroyers internationally due to size and capability. Royal Norwegian Navy operates four Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates. These ships are officially classified as frigates by Norway, but are regarded both internationally and by their officers as destroyers. They carry the Aegis combat system. They are a subclass of Spain's Álvaro de Bazán-class destroyers.

Royal Norwegian Navy operates four Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates. These ships are officially classified as frigates by Norway, but are regarded both internationally and by their officers as destroyers. They carry the Aegis combat system. They are a subclass of Spain's Álvaro de Bazán-class destroyers. Pakistan Navy Operates two Tariq-class destroyers purchased from the United Kingdom.

Pakistan Navy Operates two Tariq-class destroyers purchased from the United Kingdom. Polish Navy The Grom-class destroyer, ORP Blyskawica remains ceremonially in commission due to her historical significance.

Polish Navy The Grom-class destroyer, ORP Blyskawica remains ceremonially in commission due to her historical significance..svg.png.webp) Romanian Naval Forces operates the Mărășești. This ship was classified as a destroyer from 1990 to 2001, when she was reclassified as a frigate. No official reason was given for this and there was no change in armament or capability, thus remaining in the destroyer type.

Romanian Naval Forces operates the Mărășești. This ship was classified as a destroyer from 1990 to 2001, when she was reclassified as a frigate. No official reason was given for this and there was no change in armament or capability, thus remaining in the destroyer type. Russian Navy The Russian Navy operates 2 Sovremenny class (plus 1 in prolonged refit/reserve) and 8 Udaloy-class destroyers.

Russian Navy The Russian Navy operates 2 Sovremenny class (plus 1 in prolonged refit/reserve) and 8 Udaloy-class destroyers. Spanish Navy operates five Álvaro de Bazán-class frigates. These ships are officially classified as a frigates by Spain, but due to their size and capabilities are regarded internationally as destroyers. the design draws elements from the American Arleigh Burke-class destroyers and carry the Aegis combat system and inspired the design of the Hobart and Fridtjof Nansen-class destroyers.

Spanish Navy operates five Álvaro de Bazán-class frigates. These ships are officially classified as a frigates by Spain, but due to their size and capabilities are regarded internationally as destroyers. the design draws elements from the American Arleigh Burke-class destroyers and carry the Aegis combat system and inspired the design of the Hobart and Fridtjof Nansen-class destroyers. Royal Thai Navy Operates a single Cannon-class destroyer escort purchased from the United States for training use.

Royal Thai Navy Operates a single Cannon-class destroyer escort purchased from the United States for training use.

_underway_off_New_York_City_(USA)_on_6_August_1959_(NH_96085).jpg.webp)

Royal Navy Operates the Type 45, or Daring-class, stealth destroyer which displaces roughly 8,000 tonnes. Six ships of the class are operational. They are equipped with the UK variant of the Principal Anti-Air Missile System (PAAMS) and BAE Systems SAMPSON radar.

Royal Navy Operates the Type 45, or Daring-class, stealth destroyer which displaces roughly 8,000 tonnes. Six ships of the class are operational. They are equipped with the UK variant of the Principal Anti-Air Missile System (PAAMS) and BAE Systems SAMPSON radar. United States Navy Operates 70 active Arleigh Burke class guided missile destroyers (DDGs) of a planned class of 89, and also has two active Zumwalt-class destroyer of a planned class of three, all as of January 2021.

United States Navy Operates 70 active Arleigh Burke class guided missile destroyers (DDGs) of a planned class of 89, and also has two active Zumwalt-class destroyer of a planned class of three, all as of January 2021.

Former operators

Austro-Hungarian Navy lost its entire navy upon the Empire's collapse following World War I.

Austro-Hungarian Navy lost its entire navy upon the Empire's collapse following World War I..svg.png.webp) Navy of the Ukrainian People's Republic lost its entire navy upon its reintegration into the Soviet Union in 1921.

Navy of the Ukrainian People's Republic lost its entire navy upon its reintegration into the Soviet Union in 1921. Estonian Navy sold its two Orfey-class destroyer and Izyaslav-class destroyers to Peru in 1933, to prevent their capture by the Soviet Union.

Estonian Navy sold its two Orfey-class destroyer and Izyaslav-class destroyers to Peru in 1933, to prevent their capture by the Soviet Union. Manchukuo Imperial Navy transferred its only Momo-class destroyer back to Japan in 1942.

Manchukuo Imperial Navy transferred its only Momo-class destroyer back to Japan in 1942. Bulgarian Navy decommissioned its only Ognevoy-class destroyer in 1963.

Bulgarian Navy decommissioned its only Ognevoy-class destroyer in 1963. Royal Danish Navy decommissioned its last Hunt-class destroyer in 1965.

Royal Danish Navy decommissioned its last Hunt-class destroyer in 1965. Portuguese Navy decommissioned its last Douro-class destroyer in 1967.

Portuguese Navy decommissioned its last Douro-class destroyer in 1967. Israeli Navy decommissioned its last Z-class destroyer in 1972.

Israeli Navy decommissioned its last Z-class destroyer in 1972. Dominican Navy decommissioned its H-class destroyer in 1972.

Dominican Navy decommissioned its H-class destroyer in 1972. Republic of Vietnam Navy transferred its remaining Edsall-class destroyer escort to The Philippines in 1975 following the Fall of Saigon.

Republic of Vietnam Navy transferred its remaining Edsall-class destroyer escort to The Philippines in 1975 following the Fall of Saigon. South African Navy decommissioned its last W-class destroyer in 1976.

South African Navy decommissioned its last W-class destroyer in 1976..svg.png.webp) Yugoslav Navy decommissioned its only destroyer, Split in 1980.

Yugoslav Navy decommissioned its only destroyer, Split in 1980. Swedish Navy decommissioned both its Halland-class destroyer and four Östergötland-class destroyers in 1982 following defense reviews.

Swedish Navy decommissioned both its Halland-class destroyer and four Östergötland-class destroyers in 1982 following defense reviews. Colombian National Navy decommissioned both its Halland-class destroyers and its lone Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer in 1986.

Colombian National Navy decommissioned both its Halland-class destroyers and its lone Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer in 1986. National Navy of Uruguay decommissioned its last Cannon-class destroyer escort in 1991.

National Navy of Uruguay decommissioned its last Cannon-class destroyer escort in 1991. Tunisian National Navy lone Edsall-class destroyer escort was destroyed by a fire in 1992.

Tunisian National Navy lone Edsall-class destroyer escort was destroyed by a fire in 1992. Ecuadorian Navy decommissioned its lone Dealey-class destroyer escort in 1994.

Ecuadorian Navy decommissioned its lone Dealey-class destroyer escort in 1994. Vietnam People's Navy decommissioned its lone Edsall-class destroyer escort in 1997.

Vietnam People's Navy decommissioned its lone Edsall-class destroyer escort in 1997. Turkish Navy decommissioned its last Gearing-class destroyer in 2000.

Turkish Navy decommissioned its last Gearing-class destroyer in 2000. Polish Navy decommissioned its lone Kashin-class destroyer in 2003.

Polish Navy decommissioned its lone Kashin-class destroyer in 2003. Indonesian Navy decommissioned all four Claud Jones-class destroyer escorts in 2003.

Indonesian Navy decommissioned all four Claud Jones-class destroyer escorts in 2003. Hellenic Navy decommissioned its last Charles F. Adams-class destroyer in 2004.

Hellenic Navy decommissioned its last Charles F. Adams-class destroyer in 2004. Chilean Navy decommissioned its last County-class destroyer in 2006.

Chilean Navy decommissioned its last County-class destroyer in 2006..svg.png.webp) Peruvian Navy decommissioned its last Daring-class destroyer (1949) in 2007.

Peruvian Navy decommissioned its last Daring-class destroyer (1949) in 2007. Brazilian Navy decommissioned its last Garcia-class destroyer escort in 2008.

Brazilian Navy decommissioned its last Garcia-class destroyer escort in 2008..svg.png.webp) Bolivarian Navy of Venezuela decommissioned its last Almirante Clemente-class destroyer in 2011.

Bolivarian Navy of Venezuela decommissioned its last Almirante Clemente-class destroyer in 2011. Mexican Navy decommissioned its last Edsall-class destroyer escort in 2015.

Mexican Navy decommissioned its last Edsall-class destroyer escort in 2015. Royal Canadian Navy decommissioned its last Iroquois-class destroyer in 2017.

Royal Canadian Navy decommissioned its last Iroquois-class destroyer in 2017. Philippine Navy decommissioned its last Cannon-class destroyer escort in 2018.

Philippine Navy decommissioned its last Cannon-class destroyer escort in 2018.

Future development

.jpg.webp)

Brazilian Navy plans to build 7,000-ton destroyers after the delivery of the new frigates, and TKMS presented to the Navy its most modern 7,200-ton MEKO A-400 air defense destroyer, an updated version of the German F-125-class frigates. The similarities between the projects and the high rate of commonality between requirements were also crucial for the consortium's victory.[44]

Brazilian Navy plans to build 7,000-ton destroyers after the delivery of the new frigates, and TKMS presented to the Navy its most modern 7,200-ton MEKO A-400 air defense destroyer, an updated version of the German F-125-class frigates. The similarities between the projects and the high rate of commonality between requirements were also crucial for the consortium's victory.[44] People's Liberation Army Navy is adding six more Type 052D destroyer and sixteen more Type 055 destroyer class ships to its navy.

People's Liberation Army Navy is adding six more Type 052D destroyer and sixteen more Type 055 destroyer class ships to its navy. French Navy is adding one more FREMM multipurpose frigates to their fleet.

French Navy is adding one more FREMM multipurpose frigates to their fleet. German Navy Six multi-mission surface combat ships are planned under the name 'Mehrzweckkampfschiff 180' (MKS 180), which will have destroyer-size and corresponding capabilities (Length: 163m, displacement: 10,400 tons)[45]

German Navy Six multi-mission surface combat ships are planned under the name 'Mehrzweckkampfschiff 180' (MKS 180), which will have destroyer-size and corresponding capabilities (Length: 163m, displacement: 10,400 tons)[45] Indian Navy is building five Visakhapatnam-class destroyers.

Indian Navy is building five Visakhapatnam-class destroyers. Islamic Republic of Iran Navy is currently building 1-2 Khalije Fars-class destroyers.

Islamic Republic of Iran Navy is currently building 1-2 Khalije Fars-class destroyers. Italian Navy is currently researching development into their new DDX project to replace their Durand da le Penne-class destroyers.[46]

Italian Navy is currently researching development into their new DDX project to replace their Durand da le Penne-class destroyers.[46] Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Is developing plans for its DDR Destroyer Revolution Project.

Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Is developing plans for its DDR Destroyer Revolution Project. Republic of Korea Navy has begun development of its KDX-IIA destroyers. These ships are to be a subclass of South Korea's Chungmugong Yi Sun-shin-class destroyers. The first unit is expected to enter service in 2019. Additionally, Sejong the Great-class destroyers are being built.

Republic of Korea Navy has begun development of its KDX-IIA destroyers. These ships are to be a subclass of South Korea's Chungmugong Yi Sun-shin-class destroyers. The first unit is expected to enter service in 2019. Additionally, Sejong the Great-class destroyers are being built. Russian Navy has begun development of its Lider-class destroyer. Design work was ongoing as of 2020.[47]

Russian Navy has begun development of its Lider-class destroyer. Design work was ongoing as of 2020.[47] Turkish Navy is currently developing its TF2000-class destroyer as the largest part of the MILGEM project. A total of seven ships will be constructed and will specialise in anti-air warfare.

Turkish Navy is currently developing its TF2000-class destroyer as the largest part of the MILGEM project. A total of seven ships will be constructed and will specialise in anti-air warfare. Royal Navy is in the early stages of developing a Type 83 destroyer design after the unveiling of these plans in the 2021 defence white paper. The class is projected to replace the current Type 45 destroyer fleet beginning in the latter 2030s.[48]

Royal Navy is in the early stages of developing a Type 83 destroyer design after the unveiling of these plans in the 2021 defence white paper. The class is projected to replace the current Type 45 destroyer fleet beginning in the latter 2030s.[48] United States Navy, currently has 19 additional Arleigh Burke destroyers planned or under construction. The new ships will be the upgraded "flight III" version.[49] The United States has also started development of its DDG(X) next-generation destroyer project.[50] Construction of the first ship is expected to start in 2028.

United States Navy, currently has 19 additional Arleigh Burke destroyers planned or under construction. The new ships will be the upgraded "flight III" version.[49] The United States has also started development of its DDG(X) next-generation destroyer project.[50] Construction of the first ship is expected to start in 2028.

Preserved destroyers

A number of countries have destroyers preserved as museum ships. These include:

- HMAS Vampire (D11) in Sydney, New South Wales.

- BNS Bauru, formerly USS McAnn (DE-179) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- HMCS Haida (G63) in Hamilton, Ontario.

- Chinese destroyer Anshan (101) in Qingdao, China.

- Chinese destroyer Changchun (103) in Rushan, China

- Chinese destroyer Taiyuan (104) in Dalian, China

- Chinese destroyer Xi'an (106) in Wuhan, China

- Chinese destroyer Yinchuan (107) in Yinchuan, China

- Chinese destroyer Nanjing (131) in Shanghai, China

- Chinese destroyer Jinan (105) in Qingdao, China

- Chinese destroyer Xining (108) in Taizhou, China

- Chinese destroyer Nanchang (163) in Nanchang, China

- Chinese destroyer Chongqing (133) in Tianjin, China

- Chinese destroyer Zunyi (134), in Guizhou, China

- Chinese destroyer Dalian (110) in Shandong, China

- Chinese destroyer Hefei (132) in Shandong, China

- Chinese destroyer Zhanjiang (165) has been slated for preservation in China

- Chinese destroyer Zhuhai (166) has been slated for preservation in China

- ARC Boyaca (DE-16), formerly USS Hartley (DE-1029) in Guatape, Colombia.

- French destroyer Maille-Breze (D627) in Nantes, France.

- German destroyer Mölders (D186) in Wilhelmshaven, Germany.

- HS Velos (D-16), formerly USS Charrette (DD-581) in Palaio Faliro, Greece.[note 2]

- BRP Rajah Humabon (PS-11) in Sangley Point, Philippines

- ORP Blyskawica in Gdynia, Poland. The oldest preserved destroyer in the world.[note 3]

- Russian destroyer Bespokoynyy in Kronstadt, Russia

- Russian destroyer Smetlivy in Sevastopol, Crimea

- ROKS Jeong Ju (DD-925), formerly USS Rogers (DD-876) in Dangjin, South Korea.

- HSwMS Småland (J19) in Gothenburg, Sweden.

- ROCS Te Yang (DDG-925), formerly USS Sarsfield (DD-837) in Tainan City, Taiwan

- TCG Gayret (D352), formerly USS Eversole (DD-789) in Izmit, Turkey.

- HMS Cavalier (R73) in Chatham, Kent.

- USS Cassin Young (DD-793) in Boston, Massachusetts.

- USS The Sullivans (DD-537) in Buffalo, New York.

- USS Kidd (DD-661) in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

- USS Slater (DE-766) in Albany, New York.

- USS Stewart (DE-238) in Galveston, Texas.

- USS Orleck (DD-886) in Jacksonville, Florida.

- USS Turner Joy (DD-951) in Bremerton, Washington.

- USS Laffey (DD-724) in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.

- USS Edson (DD-946) in Bay City, Michigan.

- USS Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. (DD-850) in Fall River, Massachusetts.

Former museums

- HMCS Fraser (DDH 233) was on display in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia from 1994 to 2011. Later scrapped due to her deteriorating condition.

- IJN Shiga was on display in Chiba City, Japan from 1964 to 1998 when she was scrapped due to her deteriorating condition.

- ROKS Kang Won (DD-922) was on display from 2000 to 2016, when she was closed due to her deteriorating condition, and later scrapped.

- ROKS Jeong Buk (DD-916) was on display in Gangneung, South Korea from 1999 to 2021, when she was scrapped.

- ORP Burza was on display in Gdynia, Poland from 1951 to 1977, until she was replaced in the role by Blyskawica due to her deteriorating condition, and later scrapped.

- USS Barry (DD-933) was on display in Washington, D. C. from 1984 to 2015, until she was closed to make room for a bridge expansion. She is currently in lay up in Philadelphia awaiting scrapping.

See also

- List of destroyer classes

- United States Navy 1975 ship reclassification

- Bombardment of Cherbourg

- List of destroyers of the Second World War

Notes

- Although the Russian Kirov class are sometimes classified as battlecruisers due to their displacement, they are described by Russia as large missile cruisers.

- Velos is still a commissioned warship within the Hellenic Navy, but is strictly ceremonial and no longer sees action.

- Blyskawica is still a commissioned warship within the Polish Navy, but is strictly ceremonial and no longer sees action.

References

- Fitzsimmons, Bernard: The Illustrated encyclopedia of 20th century weapons and warfare. Columbia House, 1978, v. 8, page 835

- Smith, Charles Edgar: A short history of naval and marine engineering. Babcock & Wilcox, ltd. at the University Press, 1937, page 263

- Gove p. 2412

- Lyon pp. 8, 9

- Northrop Grumman christened its 28th Aegis guided missile destroyer, William P. Lawrence (DDG 110) April 19, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- "Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People's Republic of China 2017" (PDF). Office of the Secretary of Defense. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- Toby, A. Steven (1985). "The "Can-Do" Tin Can". Proceedings. United States Naval Institute. 111 (10): 108–113.

- Lyon p. 8

- "Torpedo Boats". Battleships-Cruisers.co.uk.

- Jentschura p. 126

- Evans and Peattie, David C. and Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-192-8.

- Howe, Christopher (1996). The Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy: Development and Technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-35485-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien: ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart (Band 4) [The German Warships: Biographies: A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present (Vol. 4)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-3-7822-0382-1.

- Lyon & Winfield. "10". The Sail and Steam Navy List. pp. 82–3.

- "Villaamil".

- "Under the influence of Fernando Villamil (1845–1898), Spain in 1886 produced the first torpedo boat destroyer." Kern, Robert & Dodge, Meredith: Historical dictionary of modern Spain, 1700–1988. Greenwood Press, 1990, page 361. ISBN 0-313-25971-2

- Polmar, Norman; Cavas, Christopher (2009). Navy's Most Wanted™: The Top 10 Book of Admirable Admirals, Sleek Submarines, and Other Naval Oddities. Potomac Books. p. 44. ISBN 978-1597976558.

- Cornwell, Edward Lewis (1979). The illustrated history of ships. Crescent Books. p. 150. ISBN 0517287951.

- Contratorpedero Destructor Archived 2010-02-26 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Illustrated Naval and Military Magazine: A monthly journal devoted to all subjects connected with Her Majesty's land and sea forces, 1888, v 9, page 280

- "The Destructor -100 Years". www.quarterdeck.org. Archived from the original on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- Captain T.D. Manning (1961). The British Destroyer. Putnam and Co.

- Lyon, David (1996). The First Destroyers. ISBN 978-1-84067-364-7.

- Simpson p. 151

- Anon. (1904). "The British Admiralty ..." Scientific American. 91 (2). ISSN 0036-8733.

- Dahl, E.J. (2001). "Naval innovation: From coal to oil" (PDF). Joint Force Quarterly (Winter 2000–01): 50–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Lyon p. 53

- Brett, Bernard: "History of World Sea Power", Deans International (London) 1985. ISBN 0-603-03723-2

- Grant p. 136

- Grant, image, frontispiece

- Lyon p. 58

- Jentschura p. 132

- Grant p. 102, 103

- Simpson p. 100

- Grant p. 42

- Grant p. 33, 34, 40

- The Königin Luise was abandoned and scuttled by its crew but the British patrol later passed through the area it had mined and a cruiser was damaged and abandoned

- Kemp, Paul (1997). U-boats Destroyed: German Submarine Losses in the World Wars. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781557508591.

- Brassey's Annual: The Armed Forces Year-book, Praeger Publishers, 1939, p. 276

- Jordan, John & Moulin, Jean (2015). French Destroyers: Torpilleurs d'Escadre & Contre-Torpilleurs 1922–1956. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-198-4.

- Johnson, Jesse (2020-01-12). "China's navy commissions biggest and 'most powerful' surface warship". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2020-11-17.

- "China Commissions Two New Type 052D Destroyers". www.defenseworld.net. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- "Military and Security Developments Involving the People's Republic of China 2017" (PDF). dod.defense.gov. 15 May 2017.

- "CCT – thyssenkrupp Marine Systems - Dr Rolf Wirtz: O nosso diferencial é a Qualidade do Produto". Defesa Net (in Portuguese). 9 January 2019.

- "Zwei weitere MKS 180 für die deutsche Marine – bundeswehr-journal". 14 February 2017.

- "Italy plans new destroyers for 2028 delivery". 9 November 2020.

- "Russia's Ambitious Shkval Nuclear Powered Destroyer Program Isn't Dead Yet". Military Watch Magazine. 5 July 2020.

- Allison, George (22 March 2021). "UK announces new Type 83 Destroyer". ukdefencejournal.org.uk.

- "Report to Congress on U.S. Navy Destroyer Programs". usni.org. 11 July 2018. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Navy Unveils Next-Generation DDG(X) Warship Concept with Hypersonic Missiles, Lasers". 12 January 2022.

Further reading

- Evans, David C. Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941, Mark R. Peattie. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland ISBN 0-87021-192-7

- Gardiner, Robert (Editor). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships (1860–1905): Naval Institute Press, 1985.

- Gove, Philip Babock (Editor in Chief). Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged. (2002) Merriam-Webster Inc., Publishers, Massachusetts, USA.

- Grant, R. Captain. Before Port Arthur in a Destroyer; The Personal Diary of a Japanese Naval Officer. London, John Murray; first and second editions published in 1907.

- Howe, Christopher. Origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy: Development and Technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War, The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-35485-7

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. United States Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland, 1977. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Lyon, David, The First Destroyers. Chatham Publishing, 1 & 2 Faulkner's Alley, Cowcross St. London, Great Britain; 1996. ISBN 1-55750-271-4.

- Sanders, Michael S. (2001) The Yard: Building a Destroyer at the Bath Iron Works, HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-06-092963-3

- Simpson, Richard V. Building The Mosquito Fleet, The US Navy's First Torpedo Boats. Arcadia Publishing, (2001); Charleston, South Carolina, USA. ISBN 0-7385-0508-0.

- Preston, Anthony. Destroyers, Bison Books (London) 1977. ISBN 0-600-32955-0

- Van der Vat, Dan. The Atlantic Campaign.

- DD-963 Spruance-class

- Navy Designates Next-Generation Zumwalt Destroyer

External links

![]() Media related to Destroyers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Destroyers at Wikimedia Commons