Philippe Pétain

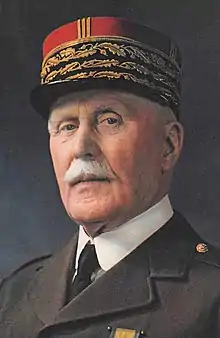

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856[1] – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (/peɪˈtæ̃/, French: [filip petɛ̃]) or Marshal Pétain (French: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World War I, during which he became known as The Lion of Verdun (French: le lion de Verdun). From 1940 to 1944, during World War II, he served as head of the collaborationist regime of Vichy France. Pétain, who was 84 years old in 1940, ranks as France's oldest head of state.

Philippe Pétain | |

|---|---|

Pétain in 1941 | |

| Chief of the French State | |

| In office 11 July 1940 – 20 August 1944 | |

| Prime Minister | Pierre Laval |

| Preceded by | Albert Lebrun (President of the Republic) |

| Succeeded by | Charles de Gaulle (Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Republic) |

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 16 June 1940 – 17 April 1942[note 1] | |

| President | Albert Lebrun (until 1940) |

| Deputy | Camille Chautemps Pierre Laval Pierre-Étienne Flandin François Darlan |

| Preceded by | Paul Reynaud |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Laval |

| Deputy Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 18 May 1940 – 16 June 1940 | |

| Prime Minister | Paul Reynaud |

| Preceded by | Camille Chautemps |

| Succeeded by | Camille Chautemps |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 9 February 1934 – 8 November 1934 | |

| Prime Minister | Gaston Doumergue |

| Preceded by | Joseph Paul-Boncour |

| Succeeded by | Louis Maurin |

| Chief of Staff of the Army | |

| In office 30 April 1917 – 16 May 1917 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Nivelle |

| Succeeded by | Ferdinand Foch |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain 24 April 1856 Cauchy-à-la-Tour, France |

| Died | 23 July 1951 (aged 95) L'Ile-d'Yeu, France |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | Treason |

| Criminal penalty | Death; commuted to life imprisonment |

| Spouse | Eugénie Hardon Pétain

(m. 1920) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Army |

| Years of service | 1873–1944 |

| Rank | General of division |

| Battles/wars | World War I Rif War World War II |

| Awards | Marshal of France Military Medal |

During World War I, Pétain led the French Army to victory at the nine-month-long Battle of Verdun. After the failed Nivelle Offensive and subsequent mutinies he was appointed Commander-in-Chief and succeeded in repairing the army's confidence. Pétain remained in command for the rest of the war and emerged as a national hero. During the interwar period he was head of the peacetime French Army, commanded joint Franco-Spanish operations during the Rif War and served twice as a government minister. During this time he was known as le vieux Maréchal (The Old Marshal).

With the imminent Fall of France and the Cabinet wanting to ask for an armistice, on 17 June 1940 Prime Minister Paul Reynaud resigned, recommending to President Albert Lebrun that he appoint Pétain in his place, which he did that day, while the government was at Bordeaux.[2] The Cabinet then resolved to sign armistice agreements with Germany and Italy. The entire government subsequently moved briefly to Clermont-Ferrand, then to the spa town of Vichy in central France. The government voted to transform the French Third Republic into the French State or Vichy France, an authoritarian regime that collaborated with the Axis. After Germany and Italy occupied and disarmed France in November 1942, Pétain's government worked very closely with the Nazi German military administration.

After the war, Pétain was tried and convicted for treason. He was originally sentenced to death, but due to his age and World War I service his sentence was commuted to life in prison. His journey from military obscurity, to hero of France during World War I, to collaborationist ruler during World War II, led his successor Charles de Gaulle to write that Pétain's life was "successively banal, then glorious, then deplorable, but never mediocre".

Early life

Pétain was born into a peasant family in Cauchy-à-la-Tour, in the Pas-de-Calais department, northern France, on 24 April 1856.[3] He was one of five children of Omer-Venant Pétain, a farmer, and Clotilde Legrand, their only son.[3] His father had previously lived in Paris, where he worked for photography pioneer Louis Daguerre, before returning to the family farm in Cauchy-à-la-Tour following the Revolution of 1848.[3] One of his great-uncles, a Catholic priest, Father Abbe Lefebvre (1771–1866), served in the Grande Armée during the Napoleonic Wars.[3]

Pétain's mother died when he was 18 months old, and he was raised by relatives after his father remarried.[3] He attended the Catholic boarding school of Saint-Bertin in the nearby town of Saint-Omer. In 1875, with the intention of preparing for the Saint-Cyr Military Academy, Pétain enrolled in the Dominican college of Albert-le-Grand in Arcueil.[3]

Early military career

Pétain was admitted to Saint-Cyr in 1873, beginning his career in the French Army. Between graduating in 1878 and 1899, he served in various garrisons with different battalions of the chasseurs,[3] the elite light infantry of the French Army. Thereafter, he alternated between staff and regimental assignments.

Pétain's career progressed slowly, as he rejected the French Army philosophy of the furious infantry assault, arguing instead that "firepower kills". His views were later proved to be correct during the First World War. He was promoted to captain in 1890 and major (chef de bataillon) in 1900. In March 1904, by then serving in the 104th Infantry, he was appointed adjunct professor of applied infantry tactics at the École Supérieure de Guerre,[4] and following promotion to lieutenant-colonel was promoted to professor on 3 April 1908.[5] He was brevetted to colonel on 1 January 1910.[6]

Unlike many French officers, Pétain served mainly in mainland France, never French Indochina or any of the African colonies, although he participated in the Rif campaign in Morocco. As colonel, he was given command of the 33rd Infantry Regiment at Arras on 25 June 1911;[7] a young lieutenant, Charles de Gaulle, who served under him, later wrote that his "first colonel, Pétain, taught (him) the Art of Command". In the spring of 1914, he was given command of a brigade (still with the rank of colonel). By then aged 58 and having been told he would never become a general, Pétain had bought a villa for retirement.[8]

First World War

Beginning of war

Pétain led his brigade at the Battle of Guise (29 August 1914). The following day, he was promoted to brigadier-general to replace Brigadier-general Pierre Peslin,[9] who had taken his own life. He was given command of the 6th Division in time for the First Battle of the Marne; little over a month later, in October 1914, he was promoted yet again and became XXXIII Corps commander. After leading his corps in the spring 1915 Artois Offensive, in July 1915 he was given command of the Second Army, which he led in the Champagne Offensive that autumn. He acquired a reputation as one of the more successful commanders on the Western Front.

Battle of Verdun

Pétain commanded the Second Army at the start of the Battle of Verdun in February 1916. During the battle, he was promoted to Commander of Army Group Centre, which contained a total of 52 divisions. Rather than holding down the same infantry divisions on the Verdun battlefield for months, akin to the German system, he rotated them out after only two weeks on the front lines. His decision to organise truck transport over the "Voie Sacrée" to bring a continuous stream of artillery, ammunition and fresh troops into besieged Verdun also played a key role in grinding down the German onslaught to a final halt in July 1916. In effect, he applied the basic principle that was a mainstay of his teachings at the École de Guerre (War College) before World War I: "le feu tue!" or "firepower kills!"—in this case meaning French field artillery, which fired over 15 million shells on the Germans during the first five months of the battle. Although Pétain did say "On les aura!" (an echoing of Joan of Arc, roughly: "We'll get them!"), the other famous quotation often attributed to him – "Ils ne passeront pas!" ("They shall not pass"!) – was actually uttered by Robert Nivelle who succeeded him in command of the Second Army at Verdun in May 1916. At the very end of 1916, Nivelle was promoted over Pétain to replace Joseph Joffre as French Commander-in-Chief.

Mutiny

Because of his high prestige as a soldier's soldier, Pétain served briefly as Army Chief of Staff (from the end of April 1917). He then became Commander-in-Chief of the entire French army, replacing General Nivelle, whose Chemin des Dames offensive failed in April 1917, thereby provoking widespread mutinies in the French Army. They involved, to various degrees, nearly half of the French infantry divisions stationed on the Western Front. Pétain restored morale by talking to the men, promising no more suicidal attacks, providing rest for exhausted units, home furloughs, and moderate discipline. He held 3400 courts martial; 554 mutineers were sentenced to death but over 90% had their sentences commuted.[10] The mutinies were kept secret from the Germans and their full extent and intensity were not revealed until decades later. Gilbert and Bernard find multiple causes:

The immediate cause was the extreme optimism and subsequent disappointment at the Nivelle offensive in the spring of 1917. Other causes were pacifism, stimulated by the Russian Revolution and the trade-union movement, and disappointment at the nonarrival of American troops.[11]

Pétain conducted some successful but limited offensives in the latter part of 1917, unlike the British who stalled in an unsuccessful offensive at Passchendaele that autumn. Pétain, instead, held off from major French offensives until the Americans arrived in force on the front lines, which did not happen until the early summer of 1918. He was also waiting for the new Renault FT tanks to be introduced in large numbers, hence his statement at the time: J'attends les chars et les Américains ("I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans").[12]

End of war

The year 1918 saw major German offensives on the Western Front. The first of these, Operation Michael in March 1918, threatened to split the British and French forces apart, and, after Pétain had threatened to retreat on Paris, the Doullens Conference was called. Just prior to the main meeting, Prime Minister Clemenceau claimed he heard Pétain say "les Allemands battront les Anglais en rase campagne, après quoi ils nous battront aussi" ("the Germans will beat the English (sic) in open country, then they'll beat us as well"). He reported this conversation to President Poincaré, adding "surely a general should not speak or think like that?" Haig recorded that Pétain had "a terrible look. He had the appearance of a commander who had lost his nerve". Pétain believed – wrongly – that Gough's Fifth Army had been routed like the Italians at Caporetto.[13] At the Conference, Ferdinand Foch was appointed as Allied Generalissimo, initially with powers to co-ordinate and deploy Allied reserves where he saw fit. Pétain eventually came to the aid of the British and secured the front with forty French divisions.

Pétain proved a capable opponent of the Germans both in defence and through counter-attack. The third offensive, "Blücher", in May 1918, saw major German advances on the Aisne, as the French Army commander (Humbert) ignored Pétain's instructions to defend in depth and instead allowed his men to be hit by the initial massive German bombardment. By the time of the last German offensives, Gneisenau and the Second Battle of the Marne, Pétain was able to defend in depth and launch counter offensives, with the new French tanks and the assistance of the Americans. Later in the year, Pétain was stripped of his right of direct appeal to the French government and requested to report to Foch, who increasingly assumed the co-ordination and ultimately the command of the Allied offensives. After the war ended Pétain was made Marshal of France on 21 November 1918.[14]

Interwar period

Respected hero of France

Pétain ended the war regarded "without a doubt, the most accomplished defensive tactician of any army" and "one of France's greatest military heroes" and was presented with his baton of Marshal of France at a public ceremony at Metz by President Raymond Poincaré on 8 December 1918.[15] He was summoned to be present at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919. His job as Commander-in-Chief came to an end with peace and demobilisation, and with Foch out of favour after his quarrel with the French government over the peace terms, it was Petain who, in January 1920, was appointed Vice-Chairman of the revived Conseil supérieur de la Guerre (Supreme War Council). This was France's highest military position, whose holder was Commander-in-Chief designate in the event of war and who had the right to overrule the Chief of the General Staff (a position held in the 1920s by Petain's protégés Buat and Debeney), and Petain would hold it until 1931.[16][17] Pétain was encouraged by friends to go into politics, although he protested that he had little interest in running for an elected position. He nevertheless tried and failed to get himself elected President following the November 1919 elections.[18]

Shortly after the war, Pétain had placed before the government plans for a large tank and air force, but "at the meeting of the Conseil supérieur de la Défense Nationale of 12 March 1920, the Finance Minister, François-Marsal, announced that although Pétain's proposals were excellent they were unaffordable". In addition, François-Marsal announced reductions – in the army from fifty-five divisions to thirty, in the air force, and did not mention tanks. It was left to the Marshals, Pétain, Joffre, and Foch, to pick up the pieces of their strategies. The General Staff, now under General Edmond Buat, began to think seriously about a line of forts along the frontier with Germany, and their report was tabled on 22 May 1922. The three Marshals supported this. The cuts in military expenditure meant that taking the offensive was now impossible and a defensive strategy was all they could have.[19]

Rif War

Pétain was appointed Inspector-General of the Army in February 1922, and produced, in concert with the new Chief of the General Staff, General Marie-Eugène Debeney, the new army manual entitled Provisional Instruction on the Tactical Employment of Large Units, which soon became known as 'the Bible'.[20] On 3 September 1925, Pétain was appointed sole Commander-in-Chief of French Forces in Morocco[21] to launch a major campaign against the Rif tribes, in concert with the Spanish Army, which was successfully concluded by the end of October. He was subsequently decorated, at Toledo, by King Alfonso XIII with the Spanish Medalla Militar.[22]

Vocal critic of defence policy

In 1924 the National Assembly was elected on a platform of reducing the length of national service to one year, to which Pétain was almost violently opposed. In January 1926, the Chief of Staff, General Debeney, proposed to the Conseil a "totally new kind of army. Only 20 infantry divisions would be maintained on a standing basis". Reserves could be called up when needed. The Conseil had no option in the straitened circumstances but to agree. Pétain, of course, disapproved of the whole thing, pointing out that North Africa still had to be defended and in itself required a substantial standing army. But he recognised, after the new Army Organisation Law of 1927, that the tide was flowing against him. He would not forget that the Radical leader, Édouard Daladier, even voted against the whole package, on the grounds that the Army was still too large.[23]

On 5 December 1925, after the Locarno Treaty, the Conseil demanded immediate action on a line of fortifications along the eastern frontier to counter the already proposed decline in manpower. A new commission for this purpose was established, under Joseph Joffre, and called for reports. In July 1927 Pétain himself went to reconnoitre the whole area. He returned with a revised plan and the commission then proposed two fortified regions. The Maginot Line, as it came to be called, (named after André Maginot the former Minister of War) thereafter occupied a good deal of Pétain's attention during 1928, when he also travelled extensively, visiting military installations up and down the country.[24] Pétain had based his strong support for the Maginot Line on his own experience of the role played by the forts during the Battle of Verdun in 1916.

Captain Charles de Gaulle continued to be a protégé of Pétain throughout these years. He even allegedly named his eldest son after the Marshal, although it is more likely that he named his son after his family ancestor Jean Baptiste Philippe de Gaulle,[25] before finally falling out over the authorship of a book he had said he had ghost-written for Pétain.

Election to the Académie française

In 1928 Pétain had supported the creation of an independent air force removed from the control of the army, and on 9 February 1931, following his retirement as Vice-Chairman of the Supreme War Council, he was appointed Inspector-General of Air Defence.[26] His first report on air defence, submitted in July that year, advocated increased expenditure.[27] In 1931 Pétain was elected a Fellow of the Académie française. By 1932 the economic situation had worsened and Édouard Herriot's government had made "severe cuts in the defence budget... orders for new weapons systems all but dried up". Summer manoeuvres in 1932 and 1933 were cancelled due to lack of funds, and recruitment to the armed forces fell off. In the latter year General Maxime Weygand claimed that "the French Army was no longer a serious fighting force". Édouard Daladier's new government retaliated against Weygand by reducing the number of officers and cutting military pensions and pay, arguing that such measures, apart from financial stringency, were in the spirit of the Geneva Disarmament Conference.[28]

In 1938 Pétain encouraged and assisted the writer André Maurois in gaining election to the Académie française – an election which was highly contested, in part due to Maurois' Jewish origin. Maurois made a point of acknowledging with thanks his debt to Pétain in his 1941 autobiography, Call no man happy – though by the time of writing their paths had sharply diverged, Pétain having become Head of State of Vichy France while Maurois went into exile and sided with the Free French.

Minister of War

Political unease was sweeping the country, and on 6 February 1934, the Paris police fired on a group of far-right rioters outside the Chamber of Deputies, killing 14 and wounding a further 236. President Lebrun invited 71-year-old Doumergue to come out of retirement and form a new "government of national unity". Pétain was invited, on 8 February, to join the new French cabinet as Minister of War, which he only reluctantly accepted after many representations. His important success that year was in getting Daladier's previous proposal to reduce the number of officers repealed. He improved the recruitment programme for specialists, and lengthened the training period by reducing leave entitlements. However Weygand reported to the Senate Army Commission that year that the French Army could still not resist a German attack. Marshals Louis Franchet d'Espèrey and Hubert Lyautey (the latter suddenly died in July) added their names to the report. After the autumn maneuvers, which Pétain had reinstated, a report was presented to Pétain that officers had been poorly instructed, had little basic knowledge, and no confidence. He was told, in addition, by Maurice Gamelin, that if the plebiscite in the Territory of the Saar Basin went for Germany "it would be a serious military error" for the French Army to intervene. Pétain responded by again petitioning the government for further funds for the army.[29] During this period, he repeatedly called for a lengthening of the term of compulsory military service for conscripts from two to three years, to no avail. Pétain accompanied President Lebrun to Belgrade for the funeral of King Alexander, who had been assassinated on 6 October 1934 in Marseille by Vlado Chernozemski, a Bulgarian nationalist from IMRO. Here he met Hermann Göring and the two men reminisced about their experiences in the Great War. "When Goering returned to Germany he spoke admiringly of Pétain, describing him as a 'man of honour'".[30]

Critic of government policy

In November the Doumergue government fell. Pétain had previously expressed interest in being named Minister of Education (as well as of War), a role in which he hoped to combat what he saw as the decay in French moral values.[31] Now, however, he refused to continue in Flandin's (short-lived) government as Minister of War and stood down – in spite of a direct appeal from Lebrun himself. At this moment an article appeared in the popular Le Petit Journal newspaper, calling for Pétain as a candidate for a dictatorship. 200,000 readers responded to the paper's poll. Pétain came first, with 47,000, ahead of Pierre Laval's 31,000 votes. These two men travelled to Warsaw for the funeral of the Polish Marshal Piłsudski in May 1935 (and another cordial meeting with Göring).[32] Although Le Petit Journal was conservative, Pétain's high reputation was bipartisan; socialist Léon Blum called him "the most human of our military commanders". Pétain did not get involved in non-military issues when in the Cabinet, and unlike other military leaders he did not have a reputation as an extreme Catholic or a monarchist.[33]

He remained on the Conseil superieur. Weygand had been at the British Army 1934 manoeuvres at Tidworth Camp in June and was appalled by what he had seen. Addressing the Conseil on the 23rd, Pétain claimed that it would be fruitless to look for assistance to Britain in the event of a German attack. On 1 March 1935, Pétain's famous article[34] appeared in the Revue des deux mondes, where he reviewed the history of the army since 1927–28. He criticised the reservist system in France, and her lack of adequate air power and armour. This article appeared just five days before Adolf Hitler's announcement of Germany's new air force and a week before the announcement that Germany was increasing its army to 36 divisions. On 26 April 1936, the general election results showed 5.5 million votes for the Popular Front parties against 4.5 million for the Right on an 84% turnout. On 3 May Pétain, was interviewed in Le Journal where he launched an attack on the Franco-Soviet Pact, on Communism in general (France had the largest communist party in Western Europe), and on those who allowed Communists intellectual responsibility. He said that France had lost faith in her destiny.[35] Pétain was now in his 80th year.

Some argue that Pétain, as France's most senior soldier after Foch's death, should bear some responsibility for the poor state of French weaponry preparation before World War II. But Pétain was only one of many military and other men on a very large committee responsible for national defence, and interwar governments frequently cut military budgets. In addition, with the restrictions imposed on Germany by the Versailles Treaty there seemed no urgency for vast expenditure until the advent of Hitler. It is argued that while Pétain supported the massive use of tanks he saw them mostly as infantry support, leading to the fragmentation of the French tank force into many types of unequal value spread out between mechanised cavalry (such as the SOMUA S35) and infantry support (mostly the Renault R35 tanks and the Char B1 bis). Modern infantry rifles and machine guns were not manufactured, with the sole exception of a light machine-rifle, the Mle 1924. The French heavy machine gun was still the Hotchkiss M1914, a capable weapon but decidedly obsolete compared to the new automatic weapons of German infantry. A modern infantry rifle was adopted in 1936 but very few of these MAS-36 rifles had been issued to the troops by 1940. A well-tested French semiautomatic rifle, the MAS 1938–39, was ready for adoption but it never reached the production stage until after World War II as the MAS 49. As to French artillery it had, basically, not been modernised since 1918. The result of all these failings is that the French Army had to face the invading enemy in 1940, with the dated weaponry of 1918. Pétain had been made, briefly, Minister of War in 1934. Yet his short period of total responsibility could not reverse 15 years of inactivity and constant cutbacks. The War Ministry was hamstrung between the wars and proved unequal to the tasks before them. French aviation entered the War in 1939 without even the prototype of a bomber aeroplane capable of reaching Berlin and coming back. French industrial efforts in fighter aircraft were dispersed among several firms (Dewoitine, Morane-Saulnier and Marcel Bloch), each with its own models. On the naval front, France had purposely overlooked building modern aircraft carriers and focused instead on four new conventional battleships, not unlike the German Navy.

Battle of France

Return into government

In March 1939, Pétain was appointed French ambassador to the newly recognized Nationalist government of Spain. Pétain had taught the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco "many years ago at France's war college" and was sent to Spain "in the hope he would win his former pupil away from Italian and German influence."[36] When World War II began in September, Daladier offered Pétain a position in his government, which Pétain turned down. However, after Germany invaded France, Pétain joined the new government of Paul Reynaud on 18 May 1940 as Deputy Prime Minister. Reynaud hoped that the hero of Verdun might instill a renewed spirit of resistance and patriotism in the French Army.[33] Reportedly Franco advised Pétain against leaving his diplomatic post in Madrid, to return to a collapsing France as a "sacrifice".[37]

By 26 May, the Allied lines had been shattered, and British forces had begun evacuating at Dunkirk. French commander-in-chief Maxime Weygand expressed his fury at British retreats and the unfulfilled promise of British fighter aircraft. He and Pétain regarded the military situation as hopeless. Colonel de Villelume subsequently stated before a parliamentary commission of inquiry in 1951 that Reynaud, as Premier of France, said to Pétain on that day that they must seek an armistice.[38] Weygand said that he was in favor of saving the French army and that he "wished to avoid internal troubles and above all anarchy". Churchill's man in Paris, Edward Spears, urged the French not to sign an armistice, saying that if French ports were occupied by Germany, Britain would have to bomb them. Spears reported that Pétain did not respond immediately but stood there "perfectly erect, with no sign of panic or emotion. He did not disguise the fact that he considered the situation catastrophic. I could not detect any sign in him of broken morale, of that mental wringing of hands and incipient hysteria noticeable in others." Pétain later remarked to Reynaud about this statement: "your ally now threatens us".

On 5 June, following the fall of Dunkirk, there was a Cabinet reshuffle. Reynaud brought into his War Cabinet as Undersecretary for War the newly promoted Brigadier-General de Gaulle, whose 4th Armoured Division had launched one of the few French counterattacks the previous month. Pétain was displeased at de Gaulle’s appointment.[39] By 8 June, Paris was threatened, and the government was preparing to depart, although Pétain was opposed to such a move. During a cabinet meeting that day, Reynaud argued that before asking for an armistice, France would have to get Britain's permission to be relieved from their accord of March 1940 not to sign a separate cease-fire. Pétain replied that "the interests of France come before those of Britain. Britain got us into this position, let us now try to get out of it." .

Fall of France

On 10 June, the government left Paris for Tours. Weygand, the Commander-in-Chief, now declared that "the fighting had become meaningless". He, Minister of Finance Paul Baudouin, and several other members of the government were already set on an armistice. On 11 June, Churchill flew to the Château du Muguet, at Briare, near Orléans, where he put forward first his idea of a Breton redoubt, to which Weygand replied that it was just a "fantasy".[40] Churchill then said the French should consider "guerrilla warfare". Pétain then replied that it would mean the destruction of the country. Churchill then said the French should defend Paris and reminded Pétain of how he had come to the aid of the British with forty divisions in March 1918, and repeating Clemenceau's words

"I will fight in front of Paris, in Paris, and behind Paris".

To this, Churchill subsequently reported, Pétain replied quietly and with dignity that he had in those days a strategic reserve of sixty divisions; now, there were none, and the British ought to be providing divisions to aid France. Making Paris into a ruin would not affect the final event. At the conference Pétain met de Gaulle for the first time in two years. Pétain noted his recent promotion to general, adding that he did not congratulate him, as ranks were of no use in defeat. When de Gaulle protested that Pétain himself had been promoted to brigadier-general and division commander at the Battle of the Marne in 1914, he replied that there was "no comparison" with the present situation. De Gaulle later conceded that Pétain was right about that much at least.[41]

On 12 June, after a second session of the conference, the cabinet met and Weygand again called for an armistice. He referred to the danger of military and civil disorder and the possibility of a Communist uprising in Paris. Pétain and Minister of Information Prouvost urged the cabinet to hear Weygand out because "he was the only one really to know what was happening".

Churchill returned to France on 13 June for another conference at Tours. Baudouin met his plane and immediately spoke to him of the hopelessness of further French resistance. Reynaud then put the cabinet's armistice proposals to Churchill, who replied that "whatever happened, we would level no reproaches against France". At that day's cabinet meeting, Pétain strongly supported Weygand’s demand for an armistice and read out a draft proposal to the cabinet where he spoke of

"the need to stay in France, to prepare a national revival, and to share the sufferings of our people. It is impossible for the government to abandon French soil without emigrating, without deserting. The duty of the government is, come what may, to remain in the country, or it could not longer be regarded as the government".

Several ministers were still opposed to an armistice, and Weygand immediately lashed out at them for even leaving Paris. Like Pétain, he said he would never leave France.[42]

The government moved to Bordeaux, where French governments had fled German invasions in 1870 and 1914, on 14 June. By coincidence, on the evening of 14 June in Bordeaux, de Gaulle dined in the same restaurant as Pétain; he came over to shake his hand in silence, and they never met again.[42]

The Assembly, both Senate and Chamber, were also at Bordeaux and immersed themselves in the armistice debate. At cabinet on 15 June, Reynaud urged that France follow the Dutch example, that the Army should lay down its arms so that the fight could be continued from abroad. Pétain was sympathetic.[43] Pétain was sent to speak to Weygand (who was waiting outside, as he was not a member of the cabinet) for around fifteen minutes.[44] Weygand persuaded him that Reynaud's suggestion would be a shameful surrender. Chautemps then put forward a 'fudge' proposal, an inquiry about terms.[43] The Cabinet voted 13-6 for the Chautemps proposal. Admiral Darlan, who had been opposed to an armistice until 15 June, now became a key player, agreeing provided the French fleet was kept out of German hands.[44]

Pétain replaces Reynaud

On Sunday, 16 June, President Roosevelt's reply to President Lebrun's requests for assistance came with only vague promises and saying that it was impossible for the President to do anything without Congressional approval. Pétain then drew a letter of resignation from his pocket, an act which was certain to bring down the government (he had persuaded Weygand to come to Bordeaux by telling him that 16 June would be the decisive day). Lebrun persuaded him to stay until Churchill’s reply had been received. After lunch, Churchill’s telegram arrived agreeing to an armistice provided the French fleet was moved to British ports, a suggestion which was not acceptable to Darlan, who argued that it was outrageous and would leave France defenceless.[43]

That afternoon the British Government offered joint nationality for Frenchmen and Britons in a Franco-British Union. Reynaud and five ministers thought these proposals acceptable. The others did not, seeing the offer as insulting and a device to make France subservient to Great Britain, as a kind of extra Dominion. Contrary to President Albert Lebrun's later recollection, no formal vote appears to have been taken at Cabinet on 16 June.[45] The outcome of the meeting is uncertain.[43] Ten ministers wanted to fight on and seven favoured an armistice (but these included the two Deputy Prime Ministers Pétain and Camille Chautemps, and this view was also favoured by the Commander-in-Chief General Weygand). Eight were initially undecided but swung towards an armistice.[45]

Lebrun reluctantly accepted Reynaud’s resignation as Prime Minister on 17 June, Reynaud recommending to the President that he appoint Marshal Petain in his place, which he did that day, while the government was at Bordeaux. Pétain already had a ministerial team ready: Pierre Laval for Foreign Affairs (this appointment was briefly vetoed by Weygand), Weygand as Minister of Defence, Darlan as Minister for the Navy, and Bouthillier for Finance.[46]

Head of the French State

The armistice

.svg.png.webp)

A new Cabinet with Pétain as head of government was formed, with Henry du Moulin de Labarthète as the Cabinet Secretary.[48] At midnight on 17 June 1940, Baudouin asked the Spanish Ambassador to submit to Germany a request to cease hostilities at once and for Germany to make known its peace terms. At 12:30 am, Pétain made his first broadcast to the French people.

"The enthusiasm of the country for the Maréchal was tremendous. He was welcomed by people as diverse as Claudel, Gide, and Mauriac, and also by the vast mass of untutored Frenchmen who saw him as their saviour."[49] General de Gaulle, no longer in the Cabinet, had arrived in London on 17 June and made a call for resistance from there on 18 June, with no legal authority whatsoever, a call that was heeded by comparatively few.

Cabinet and Parliament still argued between themselves on the question of whether or not to retreat to North Africa. On 18 June, Édouard Herriot (who would later be a prosecution witness at Pétain's trial) and Jeanneney, the presidents of the two Chambers of Parliament, as well as Lebrun said they wanted to go. Pétain said he was not departing. On 20 June, a delegation from the two chambers came to Pétain to protest at the proposed departure of President Lebrun. The next day, they went to Lebrun himself. In the event, only 26 deputies and 1 senator headed for Africa, amongst them those with Jewish backgrounds, Georges Mandel, Pierre Mendès France, and the former Popular Front Education Minister, Jean Zay.[50] Pétain broadcast again to the French people on that day.

On 22 June, France signed an armistice at Compiègne with Germany that gave Germany control over the north and west of the country, including Paris and all of the Atlantic coastline, but left the rest, around two-fifths of France's prewar territory, unoccupied. Paris remained the de jure capital. On 29 June, the French Government moved to Clermont-Ferrand where the first discussions of constitutional changes were mooted, with Pierre Laval having personal discussions with President Lebrun, who had, in the event, not departed France. On 1 July, the government, finding Clermont too cramped, moved to Vichy, at Baudouin's suggestion, the empty hotels there being more suitable for the government ministries.

Constitutional change

The Chamber of Deputies and Senate, meeting together as a "Congrès", held an emergency meeting on 10 July to ratify the armistice. At the same time, the draft constitutional proposals were tabled. The presidents of both Chambers spoke and declared that constitutional reform was necessary. The Congress voted 569–80 (with 18 abstentions) to grant the Cabinet the authority to draw up a new constitution, effectively "voting the Third Republic out of existence".[51] Nearly all French historians, as well as all postwar French governments, consider this vote to be illegal; not only were several deputies and senators not present, but the constitution explicitly stated that the republican form of government could not be changed, though it could be argued that a republican dictatorship was installed. On the next day, Pétain formally assumed near-absolute powers as "Head of State".[note 2]

Pétain was reactionary by temperament and education, and quickly began blaming the Third Republic and its endemic corruption for the French defeat. His regime soon took on clear authoritarian—and in some cases, fascist—characteristics. The republican motto of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" ("Freedom, equality, brotherhood") was replaced with "Travail, famille, patrie" ("Work, family, fatherland").[54] He issued new constitutional acts which abolished the presidency, indefinitely adjourned parliament, and also gave him full power to appoint and fire ministers and civil service members, pass laws through the Council of Ministers and designate a successor (he chose Laval). Though Pétain publicly stated that he had no desire to become "a Caesar",[55] by January 1941, Pétain held virtually all governing power in France; nearly all legislative, executive, and judicial powers were either de jure or de facto in his hands. One of his advisors commented that he had more power than any French leader since Louis XIV.[33] Fascistic and revolutionary conservative factions within the new government used the opportunity to launch an ambitious programme known as the "Révolution nationale", which rejected much of the former Third Republic's secular and liberal traditions in favour of an authoritarian and paternalist society. Pétain, amongst others, took exception to the use of the term "revolution" to describe what he believed to be an essentially conservative movement, but otherwise participated in the transformation of French society from "Republic" to "State". He added that the new France would be "a social hierarchy... rejecting the false idea of the natural equality of men."[56]

The new government immediately used its new powers to order harsh measures, including the dismissal of republican civil servants, the installation of exceptional jurisdictions, the proclamation of antisemitic laws, and the imprisonment of opponents and foreign refugees. Censorship was imposed, and freedom of expression and thought were effectively abolished with the reinstatement of the crime of "felony of opinion".

The regime organised a "Légion Française des Combattants," which included "Friends of the Legion" and "Cadets of the Legion", groups of those who had never fought but were politically attached to the new regime. Pétain championed a rural and reactionary France that spurned internationalism. As a retired military commander, he ran the country on military lines.

State collaboration with Germany

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Within months, Pétain signed antisemitic ordinances. This included the Law on the status of Jews, prohibiting Jews from exercising numerous professions, and the Law regarding foreign nationals of the Jewish race, authorizing the detention of foreign Jews. Pétain's government was nevertheless internationally recognised, notably by the U.S., at least until the German occupation of the rest of France. Neither Pétain nor his successive deputies, Laval, Pierre-Étienne Flandin, or Admiral François Darlan, gave significant resistance to requests by the Germans to indirectly aid the Axis powers. However, when Hitler met Pétain at Montoire in October 1940 to discuss the French government's role in the new "European Order", the Marshal "listened to Hitler in silence. Not once did he offer a sympathetic word for Germany." Still, the handshake he offered to Hitler caused much uproar in London, and probably influenced Britain's decision to lend Free France naval support for their operations in Gabon.[57] Furthermore, France even remained formally at war with Germany, albeit opposed to the Free French. Following the British attacks of July and September 1940 (Mers el Kébir, Dakar), the French government became increasingly fearful of the British and took the initiative to collaborate with the occupiers. Pétain accepted the government's creation of a collaborationist armed militia (the Milice) under the command of Joseph Darnand, who, along with German forces, led a campaign of repression against the French resistance ("Maquis").

.jpg.webp)

Pétain admitted Darnand into his government as Secretary of the Maintenance of Public Order (Secrétaire d'État au Maintien de l'Ordre). In August 1944, Pétain tried to distance himself from the crimes of the Milice by writing Darnand a letter of reprimand for the organisation's "excesses". Darnand sarcastically replied that Pétain should have "thought of this before".

Pétain's government acquiesced to Axis demands for large supplies of manufactured goods and foodstuffs, and also ordered French troops in the French colonial empire (in Dakar, Syria, Madagascar, Oran, and Morocco) to defend sovereign French territory against any aggressors, Allied or otherwise.

Pétain's motives are a topic of wide conjecture. Winston Churchill had spoken to Reynaud during the impending fall of France, saying of Pétain, "... he had always been a defeatist, even in the last war [World War I]."[58]

On 11 November 1942, German forces invaded the unoccupied zone of Southern France in response to Allied landings in North Africa and Admiral Darlan's agreement to support the Allies. Although the French government nominally remained in existence, civilian administration of almost all France being under it, Pétain became nothing more than a figurehead, as the Germans had negated the pretence of an "independent" government at Vichy. Pétain however remained popular and engaged in a series of visits around France as late as 1944, when he arrived in Paris on 28 April in what Nazi propaganda newsreels described as a "historic" moment for the city. Large crowds cheered him in front of the Hôtel de Ville and in the streets.[59]

Exile to Sigmaringen

On 17 August 1944, the Germans, in the person of Cecil von Renthe-Fink, "special diplomatic delegate of the Führer to the French Head of State", asked Pétain to allow himself to be transferred to the northern zone.[60] Pétain refused and asked for a written formulation of this request.[60] Renthe-Fink renewed his request twice on the 18th, then returned on the 19th, at 11:30, accompanied by General von Neubroon, who told him that he had "formal orders from Berlin".[60] The written text is submitted to Pétain: "The Reich Government instructs the transfer of the Head of State, even against his will".[60] Faced with the Marshal's continued refusal, the Germans threatened to bring in the Wehrmacht to bomb Vichy.[60] After having requested the Swiss ambassador Walter Stucki to bear witness to the Germans' blackmail, Pétain submitted. When Renthe-Fink entered the Marshal's office at the Hôtel du Parc with General Neubronn "at 7:30 p.m.", the Head of State was supervising the packing up of his suitcases and papers.[60] The next day, 20 August 1944, Pétain was taken against his will by the German army to Belfort and then, on 8 September, to Sigmaringen in southwestern Germany,[61] where dignitaries of his regime had taken refuge.

Following the liberation of France, on 7 September 1944, Pétain and other members of the French cabinet at Vichy were relocated by the Germans to the Sigmaringen enclave in Germany, where they became a government-in-exile until April 1945. Pétain, however, having been forced to leave France, refused to participate in this government and Fernand de Brinon now headed the "government commission".[62] In a note dated 29 October 1944, Pétain forbade de Brinon to use the Marshal's name in any connection with this new government, and on 5 April 1945, Pétain wrote a note to Hitler expressing his wish to return to France. No reply ever came. However, on his birthday almost three weeks later, he was taken to the Swiss border. Two days later he crossed the French frontier.[63]

Postwar life

Trial in High Court

The provisional government, headed by de Gaulle, placed Pétain on trial for treason, which took place from 23 July to 15 August 1945. Dressed in the uniform of a Marshal of France, Pétain remained silent through most of the proceedings after an initial statement that denied the right of the High Court, as constituted, to try him. De Gaulle himself later criticised the trial, stating,

Too often, the discussions took on the appearance of a partisan trial, sometimes even a settling of accounts, when the whole affair should have been treated only from the standpoint of national defence and independence.[64]

At the end of Pétain's trial, he was convicted on all charges. The jury sentenced him to death by a one-vote majority. Due to his advanced age, the court asked that the sentence not be carried out. De Gaulle, who was President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic at the end of the war, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment due to Pétain's age and his military contributions in World War I. After his conviction, the court stripped Pétain of all military ranks and honours save for the one distinction of Marshal of France.

Fearing riots at the announcement of the sentence, de Gaulle ordered that Pétain be immediately transported on the former's private aircraft to Fort du Portalet in the Pyrenees,[65] where he remained from 15 August to 16 November 1945. The government later transferred him to the Fort de Pierre-Levée citadel on the Île d'Yeu, a small island off the French Atlantic coast.[66]

Imprisonment

Over the following years Pétain's lawyers and many foreign governments and dignitaries, including Queen Mary and the Duke of Windsor, appealed to successive French governments for Pétain's release, but given the unstable state of Fourth Republic politics, no government was willing to risk unpopularity by releasing him. As early as June 1946, U.S. President Harry Truman interceded in vain for his release, even offering to provide political asylum in the U.S.[67] A similar offer was later made by the Spanish dictator General Franco.[67]

Although Pétain had still been in good health for his age at the time of his imprisonment, by late 1947, he suffered from memory lapses.[68] By January 1949, his lucid intervals were becoming fewer and fewer. On 3 March 1949, a meeting of the Council of Ministers (many of them "self-proclaimed heroes of the Resistance" in the words of biographer Charles Williams) had a fierce argument about a medical report recommending that he be moved to Val-de-Grâce (a military hospital in Paris), a measure to which Prime Minister Henri Queuille had previously been sympathetic. By May, Pétain required constant nursing care, and he was often suffering from hallucinations, e.g. that he was commanding armies in battle, or that naked women were dancing around his room.[69] By the end of 1949, Pétain was almost completely senile, with only occasional moments of lucidity. He was also beginning to suffer from heart problems and was no longer able to walk without assistance. Plans were made for his death and funeral.[70]

On 8 June 1951, President Auriol, informed that Pétain did not have much longer to live, commuted his sentence to confinement in hospital; the news was kept secret until after the elections on 17 June, but by then, Pétain was too ill to be moved to Paris.[71]

Death and burial

Pétain died in a private home in Port-Joinville on the Île d'Yeu on 23 July 1951, at the age of 95.[66] His body was buried in a local cemetery (Cimetière communal de Port-Joinville).[31] Calls were made to re-locate his remains to the grave prepared for him at Verdun.[72]

His sometime protégé, de Gaulle, later wrote that Pétain’s life was "successively banal, then glorious, then deplorable, but never mediocre".[73]

In February 1973, Pétain's coffin housing his remains was stolen from the Île d'Yeu cemetery by extremists, who demanded that President Georges Pompidou consent to its re-interment at Douaumont cemetery among the war dead of the Verdun battle. Police retrieved the coffin a few days later, and it was ceremoniously reburied with a presidential wreath in the Île d'Yeu as before.[74]

A small museum glorifying Pétain, the Historical Museum of the Île d’Yeu, displays writings and personal items of Pétain, such as his deathbed, his clothes and his cane. The museum is not publicized and rarely opens – according to its manager, to "avoid trouble".[75]

Eponymy

Mount Pétain, nearby Pétain Creek, and Pétain Falls, forming the Pétain Basin on the Continental Divide in the Canadian Rockies, were named after him in 1919,[76] while nearby summits were given the names of other French generals (Foch, Cordonnier, Mangin, Castelnau and Joffre). The names referring to Pétain were removed in 2021 and 2022, leaving the features unnamed.[77]

Hengshan Road, in Shanghai, was "Avenue Pétain" between 1922 and 1943. There is a Petain Road in Singapore in the Little India neighbourhood. Pinardville, a traditionally French-Canadian neighborhood of Goffstown, New Hampshire, has a Petain Street dating from the 1920s, alongside parallel streets named for other World War I generals, John Pershing, Douglas Haig, Ferdinand Foch, and Joseph Joffre.

Personal life

Pétain was a bachelor until his sixties, and known for his womanising.[3] After World War I Pétain married his former girlfriend, Eugénie Hardon (1877–1962) on 14 September 1920; they remained married until the end of Pétain's life.[79] After rejecting Pétain's first marriage proposal, Hardon had married and divorced François de Hérain by 1914 when she was 35. At the opening of the Battle of Verdun in 1916, Pétain is said to have been fetched during the night from a Paris hotel by a staff officer who knew that he could be found with Eugénie Hardon.[80] She had no children by Pétain but already had a son from her first marriage, Pierre de Hérain, whom Pétain strongly disliked.[68]

Military ranks

| Cadet | Sub-lieutenant | Lieutenant | Captain | Battalion chief | Lieutenant colonel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1876 | 1878 | 12 December 1883[81] | 1889 (brevet)[82] 12 July 1890 (substantive)[83] |

12 July 1900[84] | 23 March 1907[85] |

| Colonel | Brigade general | Divisional general | Divisional general holding higher command | Marshal of France | |

| 1 January 1910 (brevet)[6] | 30 August 1914[9] | 14 September 1914 | 20 April 1915[86] | 21 November 1918[87] | |

Honours and awards

French

withdrawn following conviction for high treason in 1945

Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur: 24 August 1917;[88] Grand Officer: 27 April 1916;[89] Commander: 10 May 1915;[90] Officer: ??; Knight: 1901.[91]

Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur: 24 August 1917;[88] Grand Officer: 27 April 1916;[89] Commander: 10 May 1915;[90] Officer: ??; Knight: 1901.[91] Military Medal (6 August 1918)[92]

Military Medal (6 August 1918)[92] Academic Officer (Silver Palms) (23 December 1909)[93]

Academic Officer (Silver Palms) (23 December 1909)[93] Croix de guerre 1915

Croix de guerre 1915 1914–1918 Inter-Allied Victory medal (France)

1914–1918 Inter-Allied Victory medal (France) 1914–1918 Commemorative war medal (France)

1914–1918 Commemorative war medal (France)

See also

- Battle of France

- 1917 French Army mutinies

- Historiography of the Battle of France

- Hôtel du Parc

- Vichy France

- List of ministers in Vichy France

Explanatory notes

- Although holding the position until 17 April 1942, the executive power was exercised by the Deputy Prime Ministers from 11 July 1940.

- Given full constituent powers in the law of 10 July 1940, Pétain never promulgated a new constitution. A draft was written in 1941 and signed by Pétain in 1944, but never submitted or ratified.[52][53]

References

Citations

- Government of the French empire. "Birth certificate of Pétain, Henri Philippe Benoni Omer". culture.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Werth, Alexander, France 1940-1955, London, 1957, p.30.

- Nicholas Atkin (2014). Pétain. Routledge]. ISBN 9781317897972.

- Government of the French Republic (1 April 1904). "Ecoles militaires". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (5 April 1908). "Service des ecoles militaires". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (30 December 1909). "Tableau d'avancement". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (28 June 1911). "Ministère de la guerre". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- Anne Cipriano Venzon, Paul L. Miles (1999), "Pétain, Henri-Philippe", The United States in the First World War: an encyclopedia, ISBN 9780815333531.

- Government of the French Republic (18 December 1914). "Armée active: nomination". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Nicola Barber (2003). World War I: The Western Front. Black Rabbit Books. p. 53. ISBN 9781583402689.

- Bentley B. Gilbert and Paul P. Bernard, "The French Army Mutinies of 1917", Historian (1959) 22#1, pp. 24–41.

- Mondet 2011, p. 159.

- Farrar-Hockley 1975, pp. 301–2.

- Tucker, S. C. (2009) A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, ABC-CLIO, California, p. 1738.

- Williams, 2005, p. 204.

- Williams, 2005, p. 212.

- Atkin, 1997, p. 41.

- Williams, 2005, p. 217.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 217–9.

- Williams, 2005, p. 219.

- Williams, 2005. p. 232.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 233–5.

- Williams, 2005, p. 244.

- Williams, 2005, p. 247.

- A Certain idea of France The life of Charles de Gaulle, Julian Jackson, p. 58.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 250–2.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 253–4.

- Williams, 2005, p. 257.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 260–1, 265.

- Williams, 2005, p. 266.

- Paxton, Robert O. (1982). Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944, pp. 36–37. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12469-4.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 268–9.

- Jackson, Julian (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944. Oxford University Press. pp. 124–125, 133. ISBN 0-19-820706-9.

- Philippe Pétain, "La securité de la France aux cours des années creuses", Revue des deux mondes, 26, 1935.

- Anthony Adamthwaite, Grandeur and Misery: France's Bid for Power in Europe 1914-1940 (London: Arnold, 1995), p. 182.

- "Petain appointed envoy to Burgos". The New York Times. 3 March 1939. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- John D. Bergamini. The Spanish Bourbons. ISBN 0-399-11365-7. p. 378.

- Eleanor M. Gates. End of the Affair: The Collapse of the Anglo-French Alliance, 1939-40. p. 145

- Lacouture, 1991, p. 190.

- Griffiths, Richard, Marshal Pétain, Constable, London, 1970, p. 231, ISBN 0-09-455740-3.

- Lacouture, 1991, p. 197.

- Lacouture, 1991, p. 201.

- Atkin, 1997, pp. 82–6.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 325–7.

- Lacouture, 1991, pp. 204–5.

- Lacouture, 1991, pp. 206–7.

- «Cachet de la sous-préfecture de Dinan, 6 décembre 1943, État français (Régime de Vichy)» Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Académie de Rennes.

- Jérôme Cotillon, "Un homme d’influence à Vichy: Henry du Moulin de Labarthète", Revue Historique, 2002, issue 622, pp. 353–385.

- Griffiths, 1970.

- Webster, Paul. Pétain's Crime. Pan Macmillan, London, 1990. p. 40, ISBN 0-333-57301-3.

- Griffiths, 1970, p. 248.

- Jackson, Julian (15 October 2011). "7. The Republic and Vichy". In Edward G. Berenson; Vincent Duclert; Christophe Prochasson (eds.). The French Republic: History, Values, Debates. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Cornell University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0801-46064-7. OCLC 940719314. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Beigbeder, Yves (29 August 2006). Judging War Crimes and Torture: French Justice and International Criminal Tribunals and Commissions (1940-2005). Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff/Brill. p. 140. ISBN 978-90-474-1070-6. OCLC 1058436580. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Shields, James (2007). The Extreme Right in France: From Pétain to Le Pen, pp. 15–17. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09755-X.

- 'Not a Caesar,' Petain asserts Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press, 1945-06-16.

- Mark Mazower: Dark Continent (p. 73), Penguin books, ISBN 0-14-024159-0.

- Jennings, Eric T. Free French Africa in World War II, p. 44.

- Churchill, Winston S. The Second World War, Vol 2, p. 159.

- Video on YouTube

- Aron 1962, pp. 41–42.

- Aron 1962, pp. 41–45.

- Pétain et la fin de la collaboration: Sigmaringen, 1944–1945, Henry Rousso, éditions Complexe, Paris, 1984.

- Griffiths, 1970, pp. 333–34.

- Charles De Gaulle, Mémoires de guerre, vol. 2, pp. 249–50.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 512–13.

- Association Pour Défendre la Mémoire du Maréchal Pétain (A.D.M.P.) (2009). "The World's Oldest Prisoner". Marechal-petain.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- Williams, 2005, p. 520.

- Williams, 2005, p. 523.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 527–528.

- Williams, 2005, pp. 528–529.

- Williams, 2005, p. 530.

- Dank, Milton. The French Against the French: Collaboration and Resistance, p. 361.

- Fenby, 2010, pg. 296.

- Conan, Eric; Rousso, Henry (1998). Vichy: An Ever-present Past. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. p. 21. ISBN 9780874517958.

- Méheut, Constant (10 September 2022). "'Glorious' Hero or 'Deplorable' Traitor? Pétain's Legacy Haunts French Island". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- "Pétain, Mount". BC Geographical Names.

- Kaufmann, Bill (4 July 2022). "After Calgarian's efforts, Nazi collaborator's name removed from Alberta-B.C. peak". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- Monumental battle rages over monuments. New York Press, August 30,2017 Archived 24 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 17 February 2018.

- Williams, Charles, Pétain, London, 2005, p. 206, ISBN 978-0-316-86127-4.

- Verdun 1916, by Malcolm Brown, Tempus Publishing Ltd., Stroud, UK, p. 86.

- Government of the French Republic (13 December 1883). "Armée active: nominations et promotions". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (10 April 1889). "Armée active: mutations". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (18 November 1890). "École Supérieure de Guerre". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (13 July 1900). "Armée active: promotions et nominations". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (25 March 1907). "Armée active: nominations et promotions". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (22 April 1915). "Armée active: nominations et promotions". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (22 November 1918). "Ministère de la guerre". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- Government of the French Republic (25 August 1917). "Ministere de la guerre". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (29 April 1916). "Ministere de la guerre". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (16 June 1915). "Ministere de la guerre". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (16 June 1915). "Tableaux de concours pour la Legion d'Honneur 1901". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (7 August 1918). "Ministere de la guerre". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- Government of the French Republic (1 January 1910). "Ministère de l'instruction publique et des beaux-arts". gallica.bnf.fr. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

Cited works

- Aron, Robert (1962). "Pétain: sa carriere, son procès" [Pétain: his career, his trial]. Les grands dossiers de lh́istoire contemporaine [Major issues in contemporary history]. Paris: Librairie académique Perrin. OCLC 1356008.

- Farrar-Hockley, General Sir Anthony (1975). Goughie. London: Granada. ISBN 0246640596.

- Mondet, Arlette Estienne (2011). Le général J. B. E. Estienne - père des chars: Des chenilles et des ailes [General J. B.E. Estienne - Father of tanks, Caterpillars and Wings]. Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-44757-8.

- Fenby, Jonathan. The General: Charles de Gaulle and the France He Saved (2010) ISBN 978-1-847-39410-1

- Lacouture, Jean. De Gaulle: The Rebel 1890–1944 (1984; English ed. 1991), 640 pp

Further reading

Among a vast number of books and articles about Pétain, the most complete and documented biographies are:

- Richard Griffiths, Pétain, Constable, London, 1970, ISBN 0-09-455740-3

- Herbert R. Lottman, Philippe Pétain, 1984

- Guy Pedroncini, Pétain, Le Soldat et la Gloire, Perrin, 1989, ISBN 2-262-00628-8 (in French)

- Nicholas Atkin, Pétain, Longman, 1997, ISBN 978-0-582-07037-0

- Charles Williams, Pétain, Little Brown (Time Warner Book Group UK), London, 2005, p. 206, ISBN 978-0-316-86127-4

Reputation

- Von der Goltz, Anna, and Robert Gildea. "Flawed saviours: the myths of Hindenburg and Pétain". European History Quarterly 39.3 (2009): 439-464. doi:10.1177/0265691409105061.

- Szaluta, Jacques. "Marshal Pétain and French nationalism: The interwar years and Vichy". History of European Ideas 15.1–3 (1992): 113–118. doi:10.1016/0191-6599(92)90119-W.

- Vinen, Richard. "Vichy: Pétain's Hollow Crown". History Today (June 1990) 40#6 pp. 13–19.

- Williams, Charles. Petain: How the Hero of France Became a Convicted Traitor and Changed the Course of History (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005). ISBN 9781403970114.

External links

- Article on Philippe Pétain by the Académie française

- Newspaper clippings about Philippe Pétain in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW