Unification of Germany

The unification of Germany (German: Deutsche Einigung, pronounced [ˈdɔʏtʃə ˈʔaɪnɪɡʊŋ] (![]() listen)) into the German Empire, a Prussian-dominated nation state with federal features,[1] officially occurred on 18 January 1871 at the Palace of Versailles in France. Princes of most of the German-speaking states gathered there to proclaim King Wilhelm I of Prussia as German Emperor during the Franco-Prussian War.

listen)) into the German Empire, a Prussian-dominated nation state with federal features,[1] officially occurred on 18 January 1871 at the Palace of Versailles in France. Princes of most of the German-speaking states gathered there to proclaim King Wilhelm I of Prussia as German Emperor during the Franco-Prussian War.

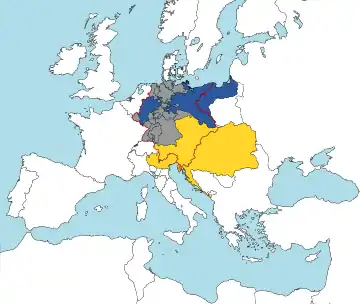

-en.png.webp) Political map of central Europe showing the 26 areas that became part of the united German Empire in 1871, including Alsace–Lorraine added from France after unification. Prussia based in the northeast, dominates in size, occupying about 40% of the new empire. | |

| Native name | Deutsche Einigung |

|---|---|

| Date | 1 February 1864 – 18 January 1871 |

| Location | Palace of Versailles, France 48°48′12.89″N 2°07′13.20″E |

| Participants | List

|

| |

A confederated realm of German princedoms, along with some adjacent lands, had been in existence for over a thousand years, dating to the Treaty of Verdun in 843. However, there was no German national identity in development as late as 1800, mainly due to the autonomous nature of the princely states; most inhabitants of the Holy Roman Empire, outside of those ruled by the emperor directly, identified themselves mainly with their prince, and not with the Empire as a whole. This became known as the practice of Kleinstaaterei, or "small-statery". By the 19th century, transportation and communications improvements brought these regions closer together. The Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806 with the abdication of Emperor Francis II during the Napoleonic Wars. Despite the legal, administrative, and political disruption caused by the dissolution, the German-speaking people of the old Empire had a common linguistic, cultural and legal tradition. European liberalism offered an intellectual basis for unification by challenging dynastic and absolutist models of social and political organization; its German manifestation emphasized the importance of tradition, education, and linguistic unity. Economically, the creation of the Prussian Zollverein (customs union) in 1818, and its subsequent expansion to include other states of the German Confederation, reduced competition between and within states. Emerging modes of transportation facilitated business and recreational travel, leading to contact and sometimes conflict between and among German-speakers from throughout Central Europe.

The model of diplomatic spheres of influence resulting from the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15 after the Napoleonic Wars endorsed Austrian dominance in Central Europe through Habsburg leadership of the German Confederation, designed to replace the Holy Roman Empire. The negotiators at Vienna took no account of Prussia's growing strength within and declined to create a second coalition of the German states under Prussia's influence, and so failed to foresee that Prussia would rise to challenge Austria for leadership of the German peoples. This German dualism presented two solutions to the problem of unification: Kleindeutsche Lösung, the small Germany solution (Germany without Austria), or Großdeutsche Lösung, the greater Germany solution (Germany with Austria).

Historians debate whether Otto von Bismarck—Minister President of Prussia—had a master plan to expand the North German Confederation of 1866 to include the remaining independent German states into a single entity or simply to expand the power of the Kingdom of Prussia. They conclude that factors in addition to the strength of Bismarck's Realpolitik led a collection of early modern polities to reorganize political, economic, military, and diplomatic relationships in the 19th century. Reaction to Danish and French nationalism provided foci for expressions of German unity. Military successes—especially those of Prussia—in three regional wars generated enthusiasm and pride that politicians could harness to promote unification. This experience echoed the memory of mutual accomplishment in the Napoleonic Wars, particularly in the War of Liberation of 1813–14. By establishing a Germany without Austria, the political and administrative unification in 1871 at least temporarily solved the problem of dualism.

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

|

|

German-speaking Central Europe in the early 19th century

Prior to the Napoleonic Wars, German-speaking Central Europe included more than 300 political entities, most of which were part of the Holy Roman Empire or the extensive Habsburg hereditary dominions. They ranged in size from the small and complex territories of the princely Hohenlohe family branches to sizable, well-defined territories such as the Kingdoms of Bavaria and Prussia. Their governance varied: they included free imperial cities, also of different sizes, such as the powerful Augsburg and the minuscule Weil der Stadt; ecclesiastical territories, also of varying sizes and influence, such as the wealthy Abbey of Reichenau and the powerful Archbishopric of Cologne; and dynastic states such as Württemberg. These lands (or parts of them—both the Habsburg domains and Hohenzollern Prussia also included territories outside the Empire structures) made up the territory of the Holy Roman Empire, which at times included more than 1,000 entities. Since the 15th century, with few exceptions, the Empire's Prince-electors had chosen successive heads of the House of Habsburg to hold the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Among the German-speaking states, the Holy Roman Empire's administrative and legal mechanisms provided a venue to resolve disputes between peasants and landlords, between jurisdictions, and within jurisdictions. Through the organization of imperial circles (Reichskreise), groups of states consolidated resources and promoted regional and organizational interests, including economic cooperation and military protection.[2]

The War of the Second Coalition (1798-1802) resulted in the defeat of the imperial and allied forces by Napoleon Bonaparte. The treaties of Lunéville (1801) and the Mediatization of 1803 secularized the ecclesiastical principalities and abolished most free imperial cities and these territories along with their inhabitants were absorbed by dynastic states. This transfer particularly enhanced the territories of Württemberg and Baden. In 1806, after a successful invasion of Prussia and the defeat of Prussia at the joint battles of Jena-Auerstedt, Napoleon dictated the Treaty of Pressburg and presided over the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine, which, inter alia, provided for the mediatization of over a hundred petty princes and counts and the absorption of their territories, as well as those of hundreds of imperial knights, by the Confederation's member-states.[3] Following the formal secession of these member-states from the Empire, the Emperor dissolved the Holy Roman Empire.[4]

Rise of German nationalism under the Napoleonic System

Under the hegemony of the French Empire (1804–1814), popular German nationalism thrived in the reorganized German states. Due in part to the shared experience, albeit under French dominance, various justifications emerged to identify "Germany" as a single state. For the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte,

The first, original, and truly natural boundaries of states are beyond doubt their internal boundaries. Those who speak the same language are joined to each other by a multitude of invisible bonds by nature herself, long before any human art begins; they understand each other and have the power of continuing to make themselves understood more and more clearly; they belong together and are by nature one and an inseparable whole.[5]

A common language may have been seen to serve as the basis of a nation, but as contemporary historians of 19th-century Germany noted, it took more than linguistic similarity to unify these several hundred polities.[6] The experience of German-speaking Central Europe during the years of French hegemony contributed to a sense of common cause to remove the French invaders and reassert control over their own lands. The exigencies of Napoleon's campaigns in Poland (1806–07), the Iberian Peninsula, western Germany, and his disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812 disillusioned many Germans, princes and peasants alike. Napoleon's Continental System nearly ruined the Central European economy. The invasion of Russia included nearly 125,000 troops from German lands, and the loss of that army encouraged many Germans, both high- and low-born, to envision a Central Europe free of Napoleon's influence.[7] The creation of student militias such as the Lützow Free Corps exemplified this tendency.[8]

The debacle in Russia loosened the French grip on the German princes. In 1813, Napoleon mounted a campaign in the German states to bring them back into the French orbit; the subsequent War of Liberation culminated in the great Battle of Leipzig, also known as the Battle of Nations. In October 1813, more than 500,000 combatants engaged in ferocious fighting over three days, making it the largest European land battle of the 19th century. The engagement resulted in a decisive victory for the Coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden, and it ended French power east of the Rhine. Success encouraged the Coalition forces to pursue Napoleon across the Rhine; his army and his government collapsed, and the victorious Coalition incarcerated Napoleon on Elba. During the brief Napoleonic restoration known as the 100 Days of 1815, forces of the Seventh Coalition, including an Anglo-Allied army under the command of the Duke of Wellington and a Prussian army under the command of Gebhard von Blücher, were victorious at Waterloo (18 June 1815).[9] The critical role played by Blücher's troops, especially after having to retreat from the field at Ligny the day before, helped to turn the tide of combat against the French. The Prussian cavalry pursued the defeated French in the evening of 18 June, sealing the allied victory. From the German perspective, the actions of Blücher's troops at Waterloo, and the combined efforts at Leipzig, offered a rallying point of pride and enthusiasm.[10] This interpretation became a key building block of the Borussian myth expounded by the pro-Prussian nationalist historians later in the 19th century.[11]

Reorganization of Central Europe and the rise of German dualism

After Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna established a new European political-diplomatic system based on the balance of power. This system reorganized Europe into spheres of influence, which, in some cases, suppressed the aspirations of the various nationalities, including the Germans and Italians.[12] Generally, an enlarged Prussia and the 38 other states consolidated from the mediatized territories of 1803 were confederated within the Austrian Empire's sphere of influence. The Congress established a loose German Confederation (1815–1866), headed by Austria, with a "Federal Diet" (called the Bundestag or Bundesversammlung, an assembly of appointed leaders) that met in the city of Frankfurt am Main. In recognition of the imperial position traditionally held by the Habsburgs, the emperors of Austria became the titular presidents of this parliament. Problematically, the built-in Austrian dominance failed to take into account Prussia's 18th-century emergence in Imperial politics. Ever since the Prince-Elector of Brandenburg had made himself King in Prussia at the beginning of that century, their domains had steadily increased through war and inheritance. Prussia's consolidated strength had become especially apparent during the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War under Frederick the Great.[13] As Maria Theresa and Joseph tried to restore Habsburg hegemony in the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick countered with the creation of the Fürstenbund (Union of Princes) in 1785. Austrian-Prussian dualism lay firmly rooted in old Imperial politics. Those balance of power manoeuvers were epitomized by the War of the Bavarian Succession, or "Potato War" among common folk. Even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire, this competition influenced the growth and development of nationalist movements in the 19th century.[14]

Problems of reorganization

Despite the nomenclature of Diet (Assembly or Parliament), this institution should in no way be construed as a broadly, or popularly, elected group of representatives. Many of the states did not have constitutions, and those that did, such as the Duchy of Baden, based suffrage on strict property requirements which effectively limited suffrage to a small portion of the male population.[16] Furthermore, this impractical solution did not reflect the new status of Prussia in the overall scheme. Although the Prussian army had been dramatically defeated in the 1806 Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, it had made a spectacular comeback at Waterloo. Consequently, Prussian leaders expected to play a pivotal role in German politics.[17]

The surge of German nationalism, stimulated by the experience of Germans in the Napoleonic period and initially allied with liberalism, shifted political, social, and cultural relationships within the German states.[18] In this context, one can detect its roots in the experience of Germans in the Napoleonic period.[19] The Burschenschaft student organizations and popular demonstrations, such as those held at Wartburg Castle in October 1817, contributed to a growing sense of unity among German speakers of Central Europe. Furthermore, implicit and sometimes explicit promises made during the German Campaign of 1813 engendered an expectation of popular sovereignty and widespread participation in the political process, promises that largely went unfulfilled once peace had been achieved. Agitation by student organizations led such conservative leaders as Klemens Wenzel, Prince von Metternich, to fear the rise of national sentiment; the assassination of German dramatist August von Kotzebue in March 1819 by a radical student seeking unification was followed on 20 September 1819 by the proclamation of the Carlsbad Decrees, which hampered intellectual leadership of the nationalist movement.[20]

Metternich was able to harness conservative outrage at the assassination to consolidate legislation that would further limit the press and constrain the rising liberal and nationalist movements. Consequently, these decrees drove the Burschenschaften underground, restricted the publication of nationalist materials, expanded censorship of the press and private correspondence, and limited academic speech by prohibiting university professors from encouraging nationalist discussion. The decrees were the subject of Johann Joseph von Görres's pamphlet Teutschland [archaic: Deutschland] und die Revolution (Germany and the Revolution) (1820), in which he concluded that it was both impossible and undesirable to repress the free utterance of public opinion by reactionary measures.[21]

Economic collaboration: the customs union

Another institution key to unifying the German states, the Zollverein, helped to create a larger sense of economic unification. Initially conceived by the Prussian Finance Minister Hans, Count von Bülow, as a Prussian customs union in 1818, the Zollverein linked the many Prussian and Hohenzollern territories. Over the ensuing thirty years (and more) other German states joined. The Union helped to reduce protectionist barriers between the German states, especially improving the transport of raw materials and finished goods, making it both easier to move goods across territorial borders and less costly to buy, transport, and sell raw materials. This was particularly important for the emerging industrial centers, most of which were located in the Prussian regions of the Rhineland, the Saar, and the Ruhr valleys.[22] States more distant from the coast joined the Customs Union earlier. Not being a member mattered more for the states of south Germany, since the external tariff of the Customs Union prevented customs-free access to the coast (which gave access to international markets). Thus, by 1836, all states to the south of Prussia had joined the Customs Union, except Austria.[23]

In contrast, the coastal states already had barrier free access to international trade and did not want consumers and producers burdened with the import duties they would pay if they were within the Zollverein customs border. Hanover on the north coast formed its own customs union – the “Tax Union” or Steuerverein – in 1834 with Brunswick and with Oldenburg in 1836. The external tariffs on finished goods and overseas raw materials were below the rates of the Zollverein. Brunswick joined the Zollverein Customs Union in 1842, while Hanover and Oldenburg finally joined in 1854[24] After the Austro-Prussian war of 1866, Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg were annexed by Prussia and thus annexed also to the Customs Union, while the two Mecklenburg states and the city states of Hamburg and Bremen joined late because they were reliant on international trade. The Mecklenburgs joined in 1867, while Bremen and Hamburg joined in 1888.[23]

Roads and railways

By the early 19th century, German roads had deteriorated to an appalling extent. Travelers, both foreign and local, complained bitterly about the state of the Heerstraßen, the military roads previously maintained for the ease of moving troops. As German states ceased to be a military crossroads, however, the roads improved; the length of hard–surfaced roads in Prussia increased from 3,800 kilometres (2,400 mi) in 1816 to 16,600 kilometres (10,300 mi) in 1852, helped in part by the invention of macadam. By 1835, Heinrich von Gagern wrote that roads were the "veins and arteries of the body politic..." and predicted that they would promote freedom, independence and prosperity.[25] As people moved around, they came into contact with others, on trains, at hotels, in restaurants, and for some, at fashionable resorts such as the spa in Baden-Baden. Water transportation also improved. The blockades on the Rhine had been removed by Napoleon's orders, but by the 1820s, steam engines freed riverboats from the cumbersome system of men and animals that towed them upstream. By 1846, 180 steamers plied German rivers and Lake Constance, and a network of canals extended from the Danube, the Weser, and the Elbe rivers.[26]

As important as these improvements were, they could not compete with the impact of the railway. German economist Friedrich List called the railways and the Customs Union "Siamese Twins", emphasizing their important relationship to one another.[27] He was not alone: the poet August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben wrote a poem in which he extolled the virtues of the Zollverein, which he began with a list of commodities that had contributed more to German unity than politics or diplomacy.[28] Historians of the German Empire later regarded the railways as the first indicator of a unified state; the patriotic novelist, Wilhelm Raabe, wrote: "The German empire was founded with the construction of the first railway..."[29] Not everyone greeted the iron monster with enthusiasm. The Prussian king Frederick William III saw no advantage in traveling from Berlin to Potsdam a few hours faster, and Metternich refused to ride in one at all. Others wondered if the railways were an "evil" that threatened the landscape: Nikolaus Lenau's 1838 poem An den Frühling (To Spring) bemoaned the way trains destroyed the pristine quietude of German forests.[30]

The Bavarian Ludwig Railway, which was the first passenger or freight rail line in the German lands, connected Nuremberg and Fürth in 1835. Although it was 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) long and only operated in daylight, it proved both profitable and popular. Within three years, 141 kilometres (88 mi) of track had been laid, by 1840, 462 kilometres (287 mi), and by 1860, 11,157 kilometres (6,933 mi). Lacking a geographically central organizing feature (such as a national capital), the rails were laid in webs, linking towns and markets within regions, regions within larger regions, and so on. As the rail network expanded, it became cheaper to transport goods: in 1840, 18 Pfennigs per ton per kilometer and in 1870, five Pfennigs. The effects of the railway were immediate. For example, raw materials could travel up and down the Ruhr Valley without having to unload and reload. Railway lines encouraged economic activity by creating demand for commodities and by facilitating commerce. In 1850, inland shipping carried three times more freight than railroads; by 1870, the situation was reversed, and railroads carried four times more. Rail travel changed how cities looked and how people traveled. Its impact reached throughout the social order, affecting the highest born to the lowest. Although some of the outlying German provinces were not serviced by rail until the 1890s, the majority of the population, manufacturing centers, and production centers were linked to the rail network by 1865.[31]

Geography, patriotism and language

As travel became easier, faster, and less expensive, Germans started to see unity in factors other than their language. The Brothers Grimm, who compiled a massive dictionary known as The Grimm, also assembled a compendium of folk tales and fables, which highlighted the story-telling parallels between different regions.[32] Karl Baedeker wrote guidebooks to different cities and regions of Central Europe, indicating places to stay, sites to visit, and giving a short history of castles, battlefields, famous buildings, and famous people. His guides also included distances, roads to avoid, and hiking paths to follow.[33]

The words of August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben expressed not only the linguistic unity of the German people but also their geographic unity. In Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles, officially called Das Lied der Deutschen ("The Song of the Germans"), Fallersleben called upon sovereigns throughout the German states to recognize the unifying characteristics of the German people.[34] Such other patriotic songs as "Die Wacht am Rhein" ("The Watch on the Rhine") by Max Schneckenburger began to focus attention on geographic space, not limiting "Germanness" to a common language. Schneckenburger wrote "The Watch on the Rhine" in a specific patriotic response to French assertions that the Rhine was France's "natural" eastern boundary. In the refrain, "Dear fatherland, dear fatherland, put your mind to rest / The watch stands true on the Rhine", and in such other patriotic poetry as Nicholaus Becker's "Das Rheinlied" ("The Rhine"), Germans were called upon to defend their territorial homeland. In 1807, Alexander von Humboldt argued that national character reflected geographic influence, linking landscape to people. Concurrent with this idea, movements to preserve old fortresses and historic sites emerged, and these particularly focused on the Rhineland, the site of so many confrontations with France and Spain.[35]

Vormärz and 19th-century liberalism

The period of Austrian and Prussian police-states and vast censorship before the Revolutions of 1848 in Germany later became widely known as the Vormärz, the "before March", referring to March 1848. During this period, European liberalism gained momentum; the agenda included economic, social, and political issues. Most European liberals in the Vormärz sought unification under nationalist principles, promoted the transition to capitalism, sought the expansion of male suffrage, among other issues. Their "radicalness" depended upon where they stood on the spectrum of male suffrage: the wider the definition of suffrage, the more radical.[36]

Hambach Festival: liberal nationalism and conservative response

Despite considerable conservative reaction, ideas of unity joined with notions of popular sovereignty in German-speaking lands. The Hambach Festival (Hambacher Fest) in May 1832 was attended by a crowd of more than 30,000.[37] Promoted as a county fair,[38] its participants celebrated fraternity, liberty, and national unity. Celebrants gathered in the town below and marched to the ruins of Hambach Castle on the heights above the small town of Hambach, in the Palatinate province of Bavaria. Carrying flags, beating drums, and singing, the participants took the better part of the morning and mid-day to arrive at the castle grounds, where they listened to speeches by nationalist orators from across the conservative to radical political spectrum. The overall content of the speeches suggested a fundamental difference between the German nationalism of the 1830s and the French nationalism of the July Revolution: the focus of German nationalism lay in the education of the people; once the populace was educated as to what was needed, they would accomplish it. The Hambach rhetoric emphasized the overall peaceable nature of German nationalism: the point was not to build barricades, a very "French" form of nationalism, but to build emotional bridges between groups.[39]

As he had done in 1819, after the Kotzebue assassination, Metternich used the popular demonstration at Hambach to push conservative social policy. The "Six Articles" of 28 June 1832 primarily reaffirmed the principle of monarchical authority. On 5 July, the Frankfurt Diet voted for an additional 10 articles, which reiterated existing rules on censorship, restricted political organizations, and limited other public activity. Furthermore, the member states agreed to send military assistance to any government threatened by unrest.[40] Prince Wrede led half of the Bavarian army to the Palatinate to "subdue" the province. Several hapless Hambach speakers were arrested, tried and imprisoned; one, Karl Heinrich Brüggemann (1810–1887), a law student and representative of the secretive Burschenschaft, was sent to Prussia, where he was first condemned to death, but later pardoned.[37]

Liberalism and the response to economic problems

Several other factors complicated the rise of nationalism in the German states. The man-made factors included political rivalries between members of the German confederation, particularly between the Austrians and the Prussians, and socio-economic competition among the commercial and merchant interests, and the old land-owning and aristocratic interests. Natural factors included widespread drought in the early 1830s, and again in the 1840s, and a food crisis in the 1840s. Further complications emerged as a result of a shift in industrialization and manufacturing; as people sought jobs, they left their villages and small towns to work during the week in the cities, returning for a day and a half on weekends.[41]

The economic, social and cultural dislocation of ordinary people, the economic hardship of an economy in transition, and the pressures of meteorological disasters all contributed to growing problems in Central Europe.[42] The failure of most of the governments to deal with the food crisis of the mid-1840s, caused by the potato blight (related to the Great Irish Famine) and several seasons of bad weather, encouraged many to think that the rich and powerful had no interest in their problems. Those in authority were concerned about the growing unrest, political and social agitation among the working classes, and the disaffection of the intelligentsia. No amount of censorship, fines, imprisonment, or banishment, it seemed, could stem the criticism. Furthermore, it was becoming increasingly clear that both Austria and Prussia wanted to be the leaders in any resulting unification; each would inhibit the drive of the other to achieve unification.[43]

First efforts at unification

Crucially, both the Wartburg rally in 1817 and the Hambach Festival in 1832 had lacked any clear-cut program of unification. At Hambach, the positions of the many speakers illustrated their disparate agendas. Held together only by the idea of unification, their notions of how to achieve this did not include specific plans but instead rested on the nebulous idea that the Volk (the people), if properly educated, would bring about unification on their own. Grand speeches, flags, exuberant students, and picnic lunches did not translate into a new political, bureaucratic, or administrative apparatus. While many spoke about the need for a constitution, no such document appeared from the discussions. In 1848, nationalists sought to remedy that problem.[44]

German revolutions of 1848 and the Frankfurt Parliament

The widespread—mainly German—revolutions of 1848–49 sought unification of Germany under a single constitution. The revolutionaries pressured various state governments, particularly those in the Rhineland, for a parliamentary assembly that would have the responsibility to draft a constitution. Ultimately, many of the left-wing revolutionaries hoped this constitution would establish universal male suffrage, a permanent national parliament, and a unified Germany, possibly under the leadership of the Prussian king. This seemed to be the most logical course since Prussia was the strongest of the German states, as well as the largest in geographic size. Generally, center-right revolutionaries sought some kind of expanded suffrage within their states and potentially, a form of loose unification. Their pressure resulted in a variety of elections, based on different voting qualifications, such as the Prussian three-class franchise, which granted to some electoral groups—chiefly the wealthier, landed ones—greater representative power.[46]

On 27 March 1849, the Frankfurt Parliament passed the Paulskirchenverfassung (Constitution of St. Paul's Church) and offered the title of Kaiser (Emperor) to the Prussian king Frederick William IV the next month. He refused for a variety of reasons. Publicly, he replied that he could not accept a crown without the consent of the actual states, by which he meant the princes. Privately, he feared opposition from the other German princes and military intervention from Austria or Russia. He also held a fundamental distaste for the idea of accepting a crown from a popularly elected parliament: he would not accept a crown of "clay".[47] Despite franchise requirements that often perpetuated many of the problems of sovereignty and political participation liberals sought to overcome, the Frankfurt Parliament did manage to draft a constitution and reach an agreement on the kleindeutsch solution. While the liberals failed to achieve the unification they sought, they did manage to gain a partial victory by working with the German princes on many constitutional issues and collaborating with them on reforms.[48]

1848 and the Frankfurt Parliament in retrospective analysis

Scholars of German history have engaged in decades of debate over how the successes and failures of the Frankfurt Parliament contribute to the historiographical explanations of German nation building. One school of thought, which emerged after The Great War and gained momentum in the aftermath of World War II, maintains that the failure of German liberals in the Frankfurt Parliament led to bourgeoisie compromise with conservatives (especially the conservative Junker landholders), which subsequently led to the so-called Sonderweg (distinctive path) of 20th-century German history.[49] Failure to achieve unification in 1848, this argument holds, resulted in the late formation of the nation-state in 1871, which in turn delayed the development of positive national values. Hitler often called on the German public to sacrifice all for the cause of their great nation, but his regime did not create German nationalism: it merely capitalized on an intrinsic cultural value of German society that still remains prevalent even to this day.[50] Furthermore, this argument maintains, the "failure" of 1848 reaffirmed latent aristocratic longings among the German middle class; consequently, this group never developed a self-conscious program of modernization.[51]

More recent scholarship has rejected this idea, claiming that Germany did not have an actual "distinctive path" any more than any other nation, a historiographic idea known as exceptionalism.[52] Instead, modern historians claim 1848 saw specific achievements by the liberal politicians. Many of their ideas and programs were later incorporated into Bismarck's social programs (e.g., social insurance, education programs, and wider definitions of suffrage). In addition, the notion of a distinctive path relies upon the underlying assumption that some other nation's path (in this case, the United Kingdom's) is the accepted norm.[53] This new argument further challenges the norms of the British-centric model of development: studies of national development in Britain and other "normal" states (e.g., France or the United States) have suggested that even in these cases, the modern nation-state did not develop evenly. Nor did it develop particularly early, being rather a largely mid-to-late-19th-century phenomenon.[54] Since the end of the 1990s, this view has become widely accepted, although some historians still find the Sonderweg analysis helpful in understanding the period of National Socialism.[55][56]

Problem of spheres of influence: The Erfurt Union and the Punctation of Olmütz

.jpg.webp)

After the Frankfurt Parliament disbanded, Frederick William IV, under the influence of General Joseph Maria von Radowitz, supported the establishment of the Erfurt Union—a federation of German states, excluding Austria—by the free agreement of the German princes. This limited union under Prussia would have almost eliminated Austrian influence on the other German states. Combined diplomatic pressure from Austria and Russia (a guarantor of the 1815 agreements that established European spheres of influence) forced Prussia to relinquish the idea of the Erfurt Union at a meeting in the small town of Olmütz in Moravia. In November 1850, the Prussians—specifically Radowitz and Frederick William—agreed to the restoration of the German Confederation under Austrian leadership. This became known as the Punctation of Olmütz, but among Prussians it was known as the "Humiliation of Olmütz."[57]

Although seemingly minor events, the Erfurt Union proposal and the Punctation of Olmütz brought the problems of influence in the German states into sharp focus. The question became not a matter of if but rather when unification would occur, and when was contingent upon strength. One of the former Frankfurt Parliament members, Johann Gustav Droysen, summed up the problem:

We cannot conceal the fact that the whole German question is a simple alternative between Prussia and Austria. In these states, German life has its positive and negative poles—in the former, all the interests [that] are national and reformative, in the latter, all that are dynastic and destructive. The German question is not a constitutional question but a question of power; and the Prussian monarchy is now wholly German, while that of Austria cannot be.[58]

Unification under these conditions raised a basic diplomatic problem. The possibility of German (or Italian) unification would overturn the overlapping spheres of influence system created in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna. The principal architects of this convention, Metternich, Castlereagh, and Tsar Alexander (with his foreign secretary Count Karl Nesselrode), had conceived of and organized a Europe balanced and guaranteed by four "great powers": Great Britain, France, Russia, and Austria, with each power having a geographic sphere of influence. France's sphere included the Iberian Peninsula and a share of influence in the Italian states. Russia's included the eastern regions of Central Europe and a balancing influence in the Balkans. Austria's sphere expanded throughout much of the Central European territories formerly held by the Holy Roman Empire. Britain's sphere was the rest of the world, especially the seas.[59]

This sphere of influence system depended upon the fragmentation of the German and Italian states, not their consolidation. Consequently, a German nation united under one banner presented significant questions. There was no readily applicable definition for who the German people would be or how far the borders of a German nation would stretch. There was also uncertainty as to who would best lead and defend "Germany", however it was defined. Different groups offered different solutions to this problem. In the Kleindeutschland ("Lesser Germany") solution, the German states would be united under the leadership of the Prussian Hohenzollerns; in the Grossdeutschland ("Greater Germany") solution, the German states would be united under the leadership of the Austrian Habsburgs. This controversy, the latest phase of the German dualism debate that had dominated the politics of the German states and Austro-Prussian diplomacy since the 1701 creation of the Kingdom of Prussia, would come to a head during the following twenty years.[60]

External expectations of a unified Germany

Other nationalists had high hopes for the German unification movement, and the frustration with lasting German unification after 1850 seemed to set the national movement back. Revolutionaries associated national unification with progress. As Giuseppe Garibaldi wrote to German revolutionary Karl Blind on 10 April 1865, "The progress of humanity seems to have come to a halt, and you with your superior intelligence will know why. The reason is that the world lacks a nation [that] possesses true leadership. Such leadership, of course, is required not to dominate other peoples but to lead them along the path of duty, to lead them toward the brotherhood of nations where all the barriers erected by egoism will be destroyed." Garibaldi looked to Germany for the "kind of leadership [that], in the true tradition of medieval chivalry, would devote itself to redressing wrongs, supporting the weak, sacrificing momentary gains and material advantage for the much finer and more satisfying achievement of relieving the suffering of our fellow men. We need a nation courageous enough to give us a lead in this direction. It would rally to its cause all those who are suffering wrong or who aspire to a better life and all those who are now enduring foreign oppression." [61]

German unification had also been viewed as a prerequisite for the creation of a European federation, which Giuseppe Mazzini and other European patriots had been promoting for more than three decades:

In the spring of 1834, while at Berne, Mazzini and a dozen refugees from Italy, Poland and Germany founded a new association with the grandiose name of Young Europe. Its basic, and equally grandiose idea, was that, as the French Revolution of 1789 had enlarged the concept of individual liberty, another revolution would now be needed for national liberty; and his vision went further because he hoped that in the no doubt distant future free nations might combine to form a loosely federal Europe with some kind of federal assembly to regulate their common interests. [...] His intention was nothing less than to overturn the European settlement agreed [to] in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, which had reestablished an oppressive hegemony of a few great powers and blocked the emergence of smaller nations. [...] Mazzini hoped, but without much confidence, that his vision of a league or society of independent nations would be realized in his own lifetime. In practice Young Europe lacked the money and popular support for more than a short-term existence. Nevertheless he always remained faithful to the ideal of a united continent for which the creation of individual nations would be an indispensable preliminary.[62]

Prussia's growing strength: Realpolitik

King Frederick William IV suffered a stroke in 1857 and could no longer rule. This led to his brother William becoming Prince Regent of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1858. Meanwhile, Helmuth von Moltke had become chief of the Prussian General Staff in 1857, and Albrecht von Roon would become Prussian Minister of War in 1859.[63] This shuffling of authority within the Prussian military establishment would have important consequences. Von Roon and William (who took an active interest in military structures) began reorganizing the Prussian army, while Moltke redesigned the strategic defense of Prussia by streamlining operational command. Prussian army reforms (especially how to pay for them) caused a constitutional crisis beginning in 1860 because both parliament and William—via his minister of war—wanted control over the military budget. William, crowned King Wilhelm I in 1861, appointed Otto von Bismarck to the position of Minister-President of Prussia in 1862. Bismarck resolved the crisis in favor of the war minister.[64]

The Crimean War of 1854–55 and the Italian War of 1859 disrupted relations among Great Britain, France, Austria, and Russia. In the aftermath of this disarray, the convergence of von Moltke's operational redesign, von Roon and Wilhelm's army restructure, and Bismarck's diplomacy influenced the realignment of the European balance of power. Their combined agendas established Prussia as the leading German power through a combination of foreign diplomatic triumphs—backed up by the possible use of Prussian military might—and an internal conservatism tempered by pragmatism, which came to be known as Realpolitik.[65]

Bismarck expressed the essence of Realpolitik in his subsequently famous "Blood and Iron" speech to the Budget Committee of the Prussian Chamber of Deputies on 30 September 1862, shortly after he became Minister President: "The great questions of the time will not be resolved by speeches and majority decisions—that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849—but by iron and blood."[66] Bismarck's words, "iron and blood" (or "blood and iron", as often attributed), have often been misappropriated as evidence of a German lust for blood and power.[67] First, the phrase from his speech "the great questions of time will not be resolved by speeches and majority decisions" is often interpreted as a repudiation of the political process—a repudiation Bismarck did not himself advocate.[68] Second, his emphasis on blood and iron did not imply simply the unrivaled military might of the Prussian army but rather two important aspects: the ability of the assorted German states to produce iron and other related war materials and the willingness to use those war materials if necessary.[69]

Founding a unified state

There is, in political geography, no Germany proper to speak of. There are Kingdoms and Grand Duchies, and Duchies and Principalities, inhabited by Germans, and each [is] separately ruled by an independent sovereign with all the machinery of State. Yet there is a natural undercurrent tending to a national feeling and toward a union of the Germans into one great nation, ruled by one common head as a national unit.

By 1862, when Bismarck made his speech, the idea of a German nation-state in the peaceful spirit of Pan-Germanism had shifted from the liberal and democratic character of 1848 to accommodate Bismarck's more conservative Realpolitik. Bismarck sought to link a unified state to the Hohenzollern dynasty, which for some historians remains one of Bismarck's primary contributions to the creation of the German Empire in 1871.[71] While the conditions of the treaties binding the various German states to one another prohibited Bismarck from taking unilateral action, the politician and diplomat in him realized the impracticality of this.[72] To get the German states to unify, Bismarck needed a single, outside enemy that would declare war on one of the German states first, thus providing a casus belli to rally all Germans behind. This opportunity arose with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Historians have long debated Bismarck's role in the events leading up to the war. The traditional view, promulgated in large part by late 19th- and early 20th-century pro-Prussian historians, maintains that Bismarck's intent was always German unification. Post-1945 historians, however, see more short-term opportunism and cynicism in Bismarck's manipulation of the circumstances to create a war, rather than a grand scheme to unify a nation-state.[73] Regardless of motivation, by manipulating events of 1866 and 1870, Bismarck demonstrated the political and diplomatic skill that had caused Wilhelm to turn to him in 1862.[74]

Three episodes proved fundamental to the unification of Germany. First, the death without male heirs of Frederick VII of Denmark led to the Second War of Schleswig in 1864. Second, the unification of Italy provided Prussia an ally against Austria in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Finally, France—fearing Hohenzollern encirclement—declared war on Prussia in 1870, resulting in the Franco-Prussian War. Through a combination of Bismarck's diplomacy and political leadership, von Roon's military reorganization, and von Moltke's military strategy, Prussia demonstrated that none of the European signatories of the 1815 peace treaty could guarantee Austria's sphere of influence in Central Europe, thus achieving Prussian hegemony in Germany and ending the dualism debate.[75]

The Schleswig-Holstein Question

The first episode in the saga of German unification under Bismarck came with the Schleswig-Holstein Question. On 15 November 1863, Christian IX became king of Denmark and duke of Schleswig, Holstein, and Lauenburg, which the Danish king held in personal union. On 18 November 1863, he signed the Danish November Constitution which replaced The Law of Sjælland and The Law of Jutland, which meant the new constitution applied to the Duchy of Schleswig. The German Confederation saw this act as a violation of the London Protocol of 1852, which emphasized the status of the Kingdom of Denmark as distinct from the three independent duchies. The German Confederation could use the ethnicities of the area as a rallying cry: Holstein and Lauenburg were largely of German origin and spoke German in everyday life, while Schleswig had a significant Danish population and history. Diplomatic attempts to have the November Constitution repealed collapsed, and fighting began when Prussian and Austrian troops crossed the Eider river on 1 February 1864.

Initially, the Danes attempted to defend their country using an ancient earthen wall known as the Danevirke, but this proved futile. The Danes were no match for the combined Prussian and Austrian forces and their modern armaments. The needle gun, one of the first bolt action rifles to be used in conflict, aided the Prussians in both this war and the Austro-Prussian War two years later. The rifle enabled a Prussian soldier to fire five shots while lying prone, while its muzzle-loading counterpart could only fire one shot and had to be reloaded while standing. The Second Schleswig War resulted in victory for the combined armies of Prussia and Austria, and the two countries won control of Schleswig and Holstein in the concluding peace of Vienna, signed on 30 October 1864.[76]

War between Austria and Prussia, 1866

The second episode in Bismarck's unification efforts occurred in 1866. In concert with the newly formed Italy, Bismarck created a diplomatic environment in which Austria declared war on Prussia. The dramatic prelude to the war occurred largely in Frankfurt, where the two powers claimed to speak for all the German states in the parliament. In April 1866, the Prussian representative in Florence signed a secret agreement with the Italian government, committing each state to assist the other in a war against Austria. The next day, the Prussian delegate to the Frankfurt assembly presented a plan calling for a national constitution, a directly elected national Diet, and universal suffrage. German liberals were justifiably skeptical of this plan, having witnessed Bismarck's difficult and ambiguous relationship with the Prussian Landtag (State Parliament), a relationship characterized by Bismarck's cajoling and riding roughshod over the representatives. These skeptics saw the proposal as a ploy to enhance Prussian power rather than a progressive agenda of reform.[77]

Choosing sides

The debate over the proposed national constitution became moot when news of Italian troop movements in Tyrol and near the Venetian border reached Vienna in April 1866. The Austrian government ordered partial mobilization in the southern regions; the Italians responded by ordering full mobilization. Despite calls for rational thought and action, Italy, Prussia, and Austria continued to rush toward armed conflict. On 1 May, Wilhelm gave von Moltke command over the Prussian armed forces, and the next day he began full-scale mobilization.[78]

In the Diet, the group of middle-sized states, known as Mittelstaaten (Bavaria, Württemberg, the grand duchies of Baden and Hesse, and the duchies of Saxony–Weimar, Saxony–Meiningen, Saxony–Coburg, and Nassau), supported complete demobilization within the Confederation. These individual governments rejected the potent combination of enticing promises and subtle (or outright) threats Bismarck used to try to gain their support against the Habsburgs. The Prussian war cabinet understood that its only supporters among the German states against the Habsburgs were two small principalities bordering on Brandenburg that had little military strength or political clout: the Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz. They also understood that Prussia's only ally abroad was Italy.[79]

Opposition to Prussia's strong-armed tactics surfaced in other social and political groups. Throughout the German states, city councils, liberal parliamentary members who favored a unified state, and chambers of commerce—which would see great benefits from unification—opposed any war between Prussia and Austria. They believed any such conflict would only serve the interests of royal dynasties. Their own interests, which they understood as "civil" or "bourgeois", seemed irrelevant. Public opinion also opposed Prussian domination. Catholic populations along the Rhine—especially in such cosmopolitan regions as Cologne and in the heavily populated Ruhr Valley—continued to support Austria. By late spring, most important states opposed Berlin's effort to reorganize the German states by force. The Prussian cabinet saw German unity as an issue of power and a question of who had the strength and will to wield that power. Meanwhile, the liberals in the Frankfurt assembly saw German unity as a process of negotiation that would lead to the distribution of power among the many parties.[80]

Austria isolated

Although several German states initially sided with Austria, they stayed on the defensive and failed to take effective initiatives against Prussian troops. The Austrian army therefore faced the technologically superior Prussian army with support only from Saxony. France promised aid, but it came late and was insufficient.[81] Complicating the situation for Austria, the Italian mobilization on Austria's southern border required a diversion of forces away from battle with Prussia to fight the Third Italian War of Independence on a second front in Venetia and on the Adriatic sea.[82]

In the day-long Battle of Königgrätz, near the village of Sadová, Friedrich Carl and his troops arrived late, and in the wrong place. Once he arrived, however, he ordered his troops immediately into the fray. The battle was a decisive victory for Prussia and forced the Habsburgs to end the war,[83] laying the groundwork for the Kleindeutschland (little Germany) solution, or "Germany without Austria."

Realpolitik and the North German Confederation

A quick peace was essential to keep Russia from entering the conflict on Austria's side.[84] Prussia annexed Hanover, Hesse-Kassel, Nassau, and the city of Frankfurt. Hesse Darmstadt lost some territory but not its sovereignty. The states south of the Main River (Baden, Württemberg, and Bavaria) signed separate treaties requiring them to pay indemnities and to form alliances bringing them into Prussia's sphere of influence. Austria, and most of its allies, were excluded from the North German Confederation.[85]

The end of Austrian dominance of the German states shifted Austria's attention to the Balkans. In 1867, the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph accepted a settlement (the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867) in which he gave his Hungarian holdings equal status with his Austrian domains, creating the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.[86] The Peace of Prague (1866) offered lenient terms to Austria, in which Austria's relationship with the new nation-state of Italy underwent major restructuring; although the Austrians were far more successful in the military field against Italian troops, the monarchy lost the important province of Venetia. The Habsburgs ceded Venetia to France, which then formally transferred control to Italy.[87] The French public resented the Prussian victory and demanded Revanche pour Sadová ("Revenge for Sadova"), illustrating anti-Prussian sentiment in France—a problem that would accelerate in the months leading up to the Franco-Prussian War.[88] The Austro-Prussian War also damaged relations with the French government. At a meeting in Biarritz in September 1865 with Napoleon III, Bismarck had let it be understood (or Napoleon had thought he understood) that France might annex parts of Belgium and Luxembourg in exchange for its neutrality in the war. These annexations did not happen, resulting in animosity from Napoleon towards Bismarck.

The reality of defeat for Austria caused a reevaluation of internal divisions, local autonomy, and liberalism.[89] The new North German Confederation had its own constitution, flag, and governmental and administrative structures. Through military victory, Prussia under Bismarck's influence had overcome Austria's active resistance to the idea of a unified Germany. Austria's influence over the German states may have been broken, but the war also splintered the spirit of pan-German unity: most of the German states resented Prussian power politics.[90]

War with France

By 1870 three of the important lessons of the Austro-Prussian war had become apparent. The first lesson was that, through force of arms, a powerful state could challenge the old alliances and spheres of influence established in 1815. Second, through diplomatic maneuvering, a skilful leader could create an environment in which a rival state would declare war first, thus forcing states allied with the "victim" of external aggression to come to the leader's aid. Finally, as Prussian military capacity far exceeded that of Austria, Prussia was clearly the only state within the Confederation (or among the German states generally) capable of protecting all of them from potential interference or aggression. In 1866, most mid-sized German states had opposed Prussia, but by 1870 these states had been coerced and coaxed into mutually protective alliances with Prussia. If a European state declared war on one of their members, then they all would come to the defense of the attacked state. With skilful manipulation of European politics, Bismarck created a situation in which France would play the role of aggressor in German affairs, while Prussia would play that of the protector of German rights and liberties.[91]

Spheres of influence fall apart in Spain

At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Metternich and his conservative allies had reestablished the Spanish monarchy under King Ferdinand VII. Over the following forty years, the great powers supported the Spanish monarchy, but events in 1868 would further test the old system. A revolution in Spain overthrew Queen Isabella II, and the throne remained empty while Isabella lived in sumptuous exile in Paris. The Spanish, looking for a suitable Catholic successor, had offered the post to three European princes, each of whom was rejected by Napoleon III, who served as regional power-broker. Finally, in 1870 the Regency offered the crown to Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, a prince of the Catholic cadet Hohenzollern line. The ensuing furor has been dubbed by historians as the Hohenzollern candidature.[92]

Over the next few weeks, the Spanish offer turned into the talk of Europe. Bismarck encouraged Leopold to accept the offer.[93] A successful installment of a Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen king in Spain would mean that two countries on either side of France would both have German kings of Hohenzollern descent. This may have been a pleasing prospect for Bismarck, but it was unacceptable to either Napoleon III or to Agenor, duc de Gramont, his minister of foreign affairs. Gramont wrote a sharply formulated ultimatum to Wilhelm, as head of the Hohenzollern family, stating that if any Hohenzollern prince should accept the crown of Spain, the French government would respond—although he left ambiguous the nature of such response. The prince withdrew as a candidate, thus defusing the crisis, but the French ambassador to Berlin would not let the issue lie.[94] He approached the Prussian king directly while Wilhelm was vacationing in Ems Spa, demanding that the King release a statement saying he would never support the installation of a Hohenzollern on the throne of Spain. Wilhelm refused to give such an encompassing statement, and he sent Bismarck a dispatch by telegram describing the French demands. Bismarck used the king's telegram, called the Ems Dispatch, as a template for a short statement to the press. With its wording shortened and sharpened by Bismarck—and further alterations made in the course of its translation by the French agency Havas—the Ems Dispatch raised an angry furor in France. The French public, still aggravated over the defeat at Sadová, demanded war.[95]

Military operations

Napoleon III had tried to secure territorial concessions from both sides before and after the Austro-Prussian War, but despite his role as mediator during the peace negotiations, he ended up with nothing. He then hoped that Austria would join in a war of revenge and that its former allies—particularly the southern German states of Baden, Württemberg, and Bavaria—would join in the cause. This hope would prove futile since the 1866 treaty came into effect and united all German states militarily—if not happily—to fight against France. Instead of a war of revenge against Prussia, supported by various German allies, France engaged in a war against all of the German states without any allies of its own.[96] The reorganization of the military by von Roon and the operational strategy of Moltke combined against France to great effect. The speed of Prussian mobilization astonished the French, and the Prussian ability to concentrate power at specific points—reminiscent of Napoleon I's strategies seventy years earlier—overwhelmed French mobilization. Utilizing their efficiently laid rail grid, Prussian troops were delivered to battle areas rested and prepared to fight, whereas French troops had to march for considerable distances to reach combat zones. After a number of battles, notably Spicheren, Wörth, Mars la Tour, and Gravelotte, the Prussians defeated the main French armies and advanced on the primary city of Metz and the French capital of Paris. They captured Napoleon III and took an entire army as prisoners at Sedan on 1 September 1870.[97]

Proclamation of the German Empire

The humiliating capture of the French emperor and the loss of the French army itself, which marched into captivity at a makeshift camp in the Saarland ("Camp Misery"), threw the French government into turmoil; Napoleon's energetic opponents overthrew his government and proclaimed the Third Republic.[98] "In the days after Sedan, Prussian envoys met with the French and demanded a large cash indemnity as well as the cession of Alsace and Lorraine. All parties in France rejected the terms, insisting that any armistice be forged “on the basis of territorial integrity.” France, in other words, would pay reparations for starting the war, but would, in Jules Favre's famous phrase, “cede neither a clod of our earth nor a stone of our fortresses".[99] The German High Command expected an overture of peace from the French, but the new republic refused to surrender. The Prussian army invested Paris and held it under siege until mid-January, with the city being "ineffectually bombarded".[100] Nevertheless, in January, the Germans fired some 12,000 shells, 300–400 grenades daily into the city.[101] On 18 January 1871, the German princes and senior military commanders proclaimed Wilhelm "German Emperor" in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.[102] Under the subsequent Treaty of Frankfurt, France relinquished most of its traditionally German regions (Alsace and the German-speaking part of Lorraine); paid an indemnity, calculated (on the basis of population) as the precise equivalent of the indemnity that Napoleon Bonaparte imposed on Prussia in 1807;[103] and accepted German administration of Paris and most of northern France, with "German troops to be withdrawn stage by stage with each installment of the indemnity payment".[104]

Importance in the unification process

.jpg.webp)

Victory in the Franco-Prussian War proved the capstone of the nationalist issue. In the first half of the 1860s, Austria and Prussia both contended to speak for the German states; both maintained they could support German interests abroad and protect German interests at home. In responding to the Schleswig-Holstein Question, they both proved equally diligent in doing so. After the victory over Austria in 1866, Prussia began internally asserting its authority to speak for the German states and defend German interests, while Austria began directing more and more of its attention to possessions in the Balkans. The victory over France in 1871 expanded Prussian hegemony in the German states (aside from Austria) to the international level. With the proclamation of Wilhelm as Kaiser, Prussia assumed the leadership of the new empire. The southern states became officially incorporated into a unified Germany at the Treaty of Versailles of 1871 (signed 26 February 1871; later ratified in the Treaty of Frankfurt of 10 May 1871), which formally ended the war.[105] Although Bismarck had led the transformation of Germany from a loose confederation into a federal nation state, he had not done it alone. Unification was achieved by building on a tradition of legal collaboration under the Holy Roman Empire and economic collaboration through the Zollverein. The difficulties of the Vormärz, the impact of the 1848 liberals, the importance of von Roon's military reorganization, and von Moltke's strategic brilliance all played a part in political unification.[106] "Einheit – unity – was achieved at the expense of Freiheit – freedom. The German Empire became," in Karl Marx's words, “a military despotism cloaked in parliamentary forms with a feudal ingredient, influenced by the bourgeoisie, festooned with bureaucrats and guarded by police.” Indeed, many historians would see Germany's “escape into war” in 1914 as a flight from all of the internal-political contradictions forged by Bismarck at Versailles in the fall of 1870.[107]

Political and administrative unification

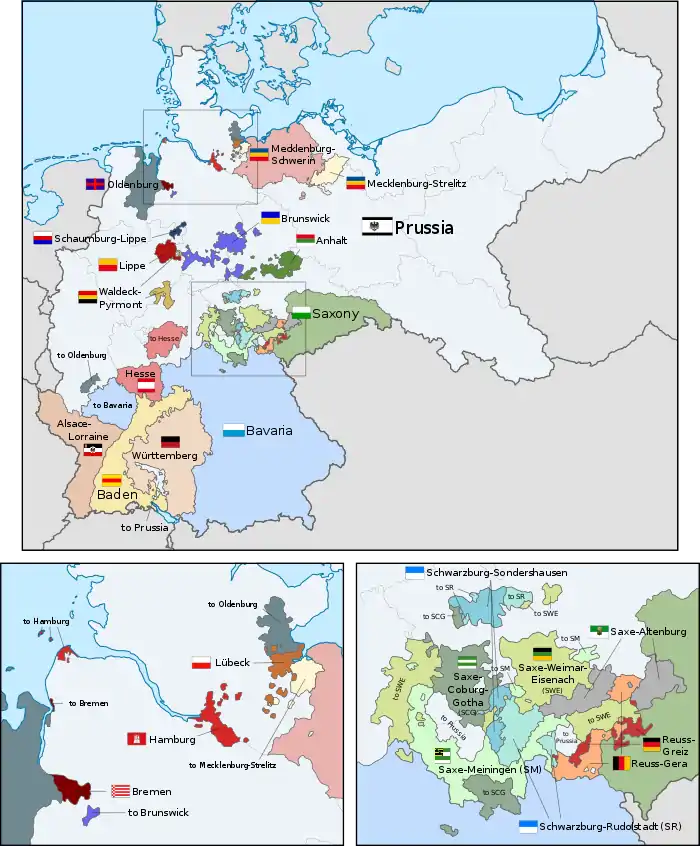

The new German Empire included 26 political entities: twenty-five constituent states (or Bundesstaaten) and one Imperial Territory (or Reichsland). It realized the Kleindeutsche Lösung ("Lesser German Solution", with the exclusion of Austria) as opposed to a Großdeutsche Lösung or "Greater German Solution", which would have included Austria. Unifying various states into one nation required more than some military victories, however much these might have boosted morale. It also required a rethinking of political, social, and cultural behaviors and the construction of new metaphors about "us" and "them". Who were the new members of this new nation? What did they stand for? How were they to be organized?[108]

Constituent states of the Empire

Though often characterized as a federation of monarchs, the German Empire, strictly speaking, federated a group of 26 constituent entities with different forms of government, ranging from the main four constitutional monarchies to the three republican Hanseatic cities.[109]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Political structure of the Empire

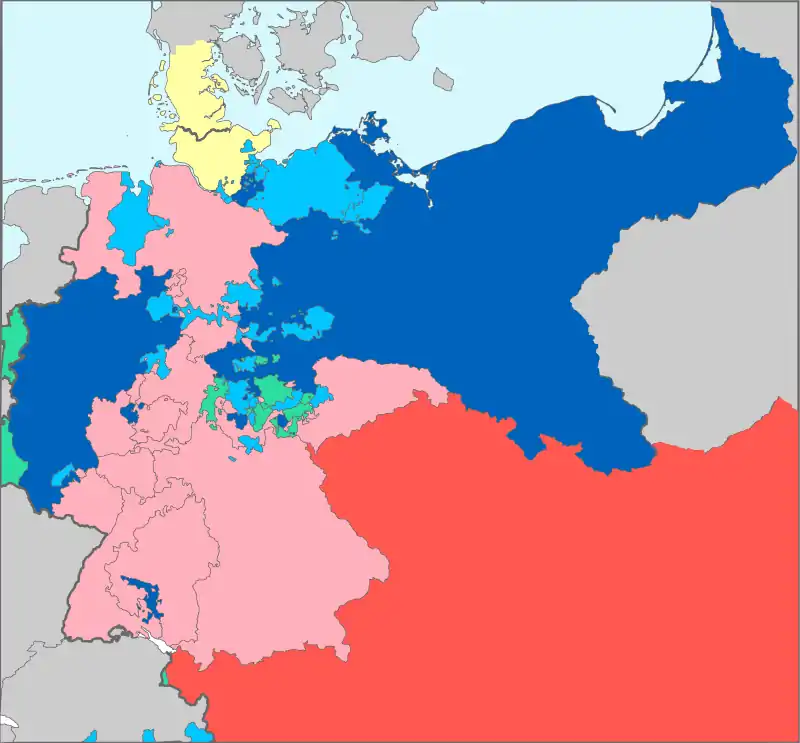

The 1866 North German Constitution became (with some semantic adjustments) the 1871 Constitution of the German Empire. With this constitution, the new Germany acquired some democratic features: notably the Imperial Diet, which—in contrast to the parliament of Prussia—gave citizens representation on the basis of elections by direct and equal suffrage of all males who had reached the age of 25. Furthermore, elections were generally free of chicanery, engendering pride in the national parliament.[110] However, legislation required the consent of the Bundesrat, the federal council of deputies from the states, in and over which Prussia had a powerful influence; Prussia could appoint 17 of 58 delegates with only 14 votes needed for a veto. Prussia thus exercised influence in both bodies, with executive power vested in the Prussian King as Kaiser, who appointed the federal chancellor. The chancellor was accountable solely to, and served entirely at the discretion of, the Emperor. Officially, the chancellor functioned as a one-man cabinet and was responsible for the conduct of all state affairs; in practice, the State Secretaries (bureaucratic top officials in charge of such fields as finance, war, foreign affairs, etc.) acted as unofficial portfolio ministers. With the exception of the years 1872–1873 and 1892–1894, the imperial chancellor was always simultaneously the prime minister of the imperial dynasty's hegemonic home-kingdom, Prussia. The Imperial Diet had the power to pass, amend, or reject bills, but it could not initiate legislation. (The power of initiating legislation rested with the chancellor.) The other states retained their own governments, but the military forces of the smaller states came under Prussian control. The militaries of the larger states (such as the Kingdoms of Bavaria and Saxony) retained some autonomy, but they underwent major reforms to coordinate with Prussian military principles and came under federal government control in wartime.[111]

Historical arguments and the Empire's social anatomy

The Sonderweg hypothesis attributed Germany's difficult 20th century to the weak political, legal, and economic basis of the new empire. The Prussian landed elites, the Junkers, retained a substantial share of political power in the unified state. The Sonderweg hypothesis attributed their power to the absence of a revolutionary breakthrough by the middle classes, or by peasants in combination with the urban workers, in 1848 and again in 1871. Recent research into the role of the Grand Bourgeoisie—which included bankers, merchants, industrialists, and entrepreneurs—in the construction of the new state has largely refuted the claim of political and economic dominance of the Junkers as a social group. This newer scholarship has demonstrated the importance of the merchant classes of the Hanseatic cities and the industrial leadership (the latter particularly important in the Rhineland) in the ongoing development of the Second Empire.[112]

Additional studies of different groups in Wilhelmine Germany have all contributed to a new view of the period. Although the Junkers did, indeed, continue to control the officer corps, they did not dominate social, political, and economic matters as much as the Sonderweg theorists had hypothesized. Eastern Junker power had a counterweight in the western provinces in the form of the Grand Bourgeoisie and in the growing professional class of bureaucrats, teachers, professors, doctors, lawyers, scientists, etc.[113]

Beyond the political mechanism: forming a nation

If the Wartburg and Hambach rallies had lacked a constitution and administrative apparatus, that problem was addressed between 1867 and 1871. Yet, as Germans discovered, grand speeches, flags, and enthusiastic crowds, a constitution, a political reorganization, and the provision of an imperial superstructure; and the revised Customs Union of 1867–68, still did not make a nation.[114]

A key element of the nation-state is the creation of a national culture, frequently—although not necessarily—through deliberate national policy.[115] In the new German nation, a Kulturkampf (1872–78) that followed political, economic, and administrative unification attempted to address, with a remarkable lack of success, some of the contradictions in German society. In particular, it involved a struggle over language, education, and religion. A policy of Germanization of non-German people of the empire's population, including the Polish and Danish minorities, started with language, in particular, the German language, compulsory schooling (Germanization), and the attempted creation of standardized curricula for those schools to promote and celebrate the idea of a shared past. Finally, it extended to the religion of the new Empire's population.[116]

Kulturkampf

For some Germans, the definition of nation did not include pluralism, and Catholics in particular came under scrutiny; some Germans, and especially Bismarck, feared that the Catholics' connection to the papacy might make them less loyal to the nation. As chancellor, Bismarck tried without much success to limit the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and of its party-political arm, the Catholic Center Party, in schools and education- and language-related policies. The Catholic Center Party remained particularly well entrenched in the Catholic strongholds of Bavaria and southern Baden, and in urban areas that held high populations of displaced rural workers seeking jobs in the heavy industry, and sought to protect the rights not only of Catholics, but other minorities, including the Poles, and the French minorities in the Alsatian lands.[117] The May Laws of 1873 brought the appointment of priests, and their education, under the control of the state, resulting in the closure of many seminaries, and a shortage of priests. The Congregations Law of 1875 abolished religious orders, ended state subsidies to the Catholic Church, and removed religious protections from the Prussian constitution.[118]

Integrating the Jewish community

The Germanized Jews remained another vulnerable population in the new German nation-state. Since 1780, after emancipation by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, Jews in the former Habsburg territories had enjoyed considerable economic and legal privileges that their counterparts in other German-speaking territories did not: they could own land, for example, and they did not have to live in a Jewish quarter (also called the Judengasse, or "Jews' alley"). They could also attend universities and enter the professions. During the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, many of the previously strong barriers between Jews and Christians broke down. Napoleon had ordered the emancipation of Jews throughout territories under French hegemony. Like their French counterparts, wealthy German Jews sponsored salons; in particular, several Jewish salonnières held important gatherings in Frankfurt and Berlin during which German intellectuals developed their own form of republican intellectualism. Throughout the subsequent decades, beginning almost immediately after the defeat of the French, reaction against the mixing of Jews and Christians limited the intellectual impact of these salons. Beyond the salons, Jews continued a process of Germanization in which they intentionally adopted German modes of dress and speech, working to insert themselves into the emerging 19th-century German public sphere. The religious reform movement among German Jews reflected this effort.[119]

By the years of unification, German Jews played an important role in the intellectual underpinnings of the German professional, intellectual, and social life. The expulsion of Jews from Russia in the 1880s and 1890s complicated integration into the German public sphere. Russian Jews arrived in north German cities in the thousands; considerably less educated and less affluent, their often dismal poverty dismayed many of the Germanized Jews. Many of the problems related to poverty (such as illness, overcrowded housing, unemployment, school absenteeism, refusal to learn German, etc.) emphasized their distinctiveness for not only the Christian Germans, but for the local Jewish populations as well.[120]

Writing the story of the nation

Another important element in nation-building, the story of the heroic past, fell to such nationalist German historians as the liberal constitutionalist Friedrich Dahlmann (1785–1860), his conservative student Heinrich von Treitschke (1834–1896), and others less conservative, such as Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903) and Heinrich von Sybel (1817–1895), to name two. Dahlmann himself died before unification, but he laid the groundwork for the nationalist histories to come through his histories of the English and French revolutions, by casting these revolutions as fundamental to the construction of a nation, and Dahlmann himself viewed Prussia as the logical agent of unification.[121]

Heinrich von Treitschke's History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century, published in 1879, has perhaps a misleading title: it privileges the history of Prussia over the history of other German states, and it tells the story of the German-speaking peoples through the guise of Prussia's destiny to unite all German states under its leadership. The creation of this Borussian myth (Borussia is the Latin name for Prussia) established Prussia as Germany's savior; it was the destiny of all Germans to be united, this myth maintains, and it was Prussia's destiny to accomplish this.[122] According to this story, Prussia played the dominant role in bringing the German states together as a nation-state; only Prussia could protect German liberties from being crushed by French or Russian influence. The story continues by drawing on Prussia's role in saving Germans from the resurgence of Napoleon's power in 1815, at Waterloo, creating some semblance of economic unity, and uniting Germans under one proud flag after 1871.[123]

Mommsen's contributions to the Monumenta Germaniae Historica laid the groundwork for additional scholarship on the study of the German nation, expanding the notion of "Germany" to mean other areas beyond Prussia. A liberal professor, historian, and theologian, and generally a titan among late 19th-century scholars, Mommsen served as a delegate to the Prussian House of Representatives from 1863 to 1866 and 1873 to 1879; he also served as a delegate to the Reichstag from 1881 to 1884, for the liberal German Progress Party (Deutsche Fortschrittspartei) and later for the National Liberal Party. He opposed the antisemitic programs of Bismarck's Kulturkampf and the vitriolic text that Treitschke often employed in the publication of his Studien über die Judenfrage (Studies of the Jewish Question), which encouraged assimilation and Germanization of Jews.[124]

See also

- Italian unification

- Formation of Romania

- Reichsbürgerbewegung

Footnotes

References

- Oliver F. R. Haardt, The Federal Evolution of Imperial Germany (1871–1918).

- See, for example, James Allen Vann, The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. Vol. LII, Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. Bruxelles, 1975. Mack Walker. German home towns: community, state, and general estate, 1648–1871. Ithaca, 1998.

- John G. Gagliardo, Reich and Nation. The Holy Roman Empire as Idea and Reality, 1763–1806, Indiana University Press, 1980, p. 278–279.

- Robert A. Kann. History of the Habsburg Empire: 1526–1918, Los Angeles, 1974, p. 221. In his abdication, Francis released all former estates from their duties and obligations to him, and took upon himself solely the title of King of Austria, which had been established since 1804. Golo Mann, Deutsche Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt am Main, 2002, p. 70.

- Fichte, Johann Gottlieb (1808). "Address to the German Nation". www.historyman.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- James J. Sheehan, German History, 1780–1866, Oxford, 1989, p. 434.

- Jakob Walter, and Marc Raeff. The diary of a Napoleonic foot soldier. Princeton, N.J., 1996.

- Sheehan, pp. 384–387.

- Although the Prussian army had gained its reputation in the Seven Years' War, its humiliating defeat at Jena and Auerstadt crushed the pride many Prussians felt in their soldiers. During their Russian exile, several officers, including Carl von Clausewitz, contemplated reorganization and new training methods. Sheehan, p. 323.

- Sheehan, pp. 322–323.

- David Blackbourn and Geoff Eley. The Peculiarities of German History: Bourgeois Society and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Germany. Oxford & New York, 1984, part 1; Thomas Nipperdey, German History From Napoleon to Bismarck, 1800–1871, New York, Oxford, 1983. Chapter 1.

- Sheehan, pp. 398–410; Hamish Scott, The Birth of a Great Power System, 1740–1815, US, 2006, pp. 329–361.

- Sheehan, pp. 398–410.

- Jean Berenger. A History of the Habsburg Empire 1700–1918. C. Simpson, Trans. New York: Longman, 1997, ISBN 0-582-09007-5. pp. 96–97.

- Sheehan, pp. 460–470. German Historical Institute

- Lloyd Lee, Politics of Harmony: Civil Service, Liberalism, and Social Reform in Baden, 1800–1850, Cranbury, New Jersey, 1980.

- Adam Zamoyski, Rites of Peace: The Fall of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna, New York, 2007, pp. 98–115, 239–40.

- L.B. Namier, (1952) Avenues of History. London, ONT, 1952, p. 34.

- Nipperdey, pp. 1–3.

- Sheehan, pp. 407–408, 444.

- Sheehan, pp. 442–445.

- Sheehan, pp. 465–467; Blackbourn, Long Century, pp. 106–107.

- Wolfgang Keller and Carol Shiue, The Trade Impact of the Customs Union, Boulder, University of Colorado, 5 March 2013, pp.10 and 18

- Florian Ploeckl. The Zollverein and the Formation of a Customs Union, Discussion Paper no. 84 in the Economic and Social History series, Nuffield College, Oxford, Nuffield College. Retrieved from www.nuff.ox.ac.uk/Economics/History March 2017; p. 23

- Sheehan, p. 465.

- Sheehan, p. 466.

- Sheehan, pp. 467–468.

- Sheehan, p. 502.

- Sheehan, p. 469.

- Sheehan, p. 458.

- Sheehan, pp. 466–467.