Long COVID

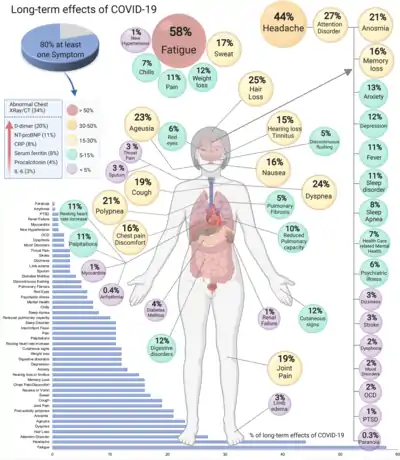

Long COVID or long-haul COVID (also known as post-COVID-19 syndrome, post-COVID-19 condition,[1][2] post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), or chronic COVID syndrome (CCS)[3][4][5]) is a condition characterized by long-term health problems persisting or appearing after the typical recovery period of COVID-19. Although studies into long COVID are under way, as of May 2022 there is no consensus on the definition of the term.[6] Long COVID has been described as having the potential to affect nearly every organ system, causing further conditions (sequelae) including respiratory system disorders, nervous system and neurocognitive disorders, mental health disorders, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, musculoskeletal pain, and anemia.[7]

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

Scientifically accurate atomic model of the external structure of SARS-CoV-2. Each "ball" is an atom. |

|

|

|

The most commonly reported symptoms of long COVID are fatigue and memory problems.[8][9] Many other symptoms have also been reported, including malaise, headaches, shortness of breath, anosmia (loss of smell), parosmia (distorted smell), muscle weakness, low fever and cognitive dysfunction.[10] Overall, it is considered by default to be a diagnosis of exclusion.[11]

Estimates of the prevalence of long COVID vary based on definition, population studied, time period studied, and methodology, generally ranging between 5% and 50%.[12] Health systems in some countries and jurisdictions have been mobilized to deal with this group of patients by creating specialized clinics and providing advice.[13][14][15]

Terminology and definitions

Overview

Long COVID is a patient-created term which was reportedly first used in May 2020 as a hashtag on Twitter by Elisa Perego, an archaeologist at University College London.[16][17]

Long COVID has no single, strict definition.[18][19] It is normal and expected that people who experience severe symptoms or complications such as post-intensive care syndrome or secondary infections will take longer to recover than people who did not require hospitalization (called mild COVID-19[20]) and had no such complications. It can be difficult to determine whether an individual's set of ongoing symptoms represents a normal, prolonged convalescence, or extended 'long COVID'. One rule of thumb is that long COVID represents symptoms that have been present for longer than two months, though there is no reason to believe that this choice of cutoff is specific to infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus.[18]

World Health Organization clinical case definition

The World Health Organization (WHO) established a clinical case definition in October 2021,[1] published in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases:[2]

post-COVID-19 condition occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset, with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Common symptoms include, but are not limited to, fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction, and generally have an impact on everyday functioning. Symptoms might be new onset following initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness. Symptoms might also fluctuate or relapse over time.

British definition

The British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) divides COVID-19 into three clinical case definitions:

- acute COVID-19 for signs and symptoms during the first four weeks after infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the first, and

- long Covid for new or ongoing symptoms four weeks or more after the start of acute COVID-19, which is divided into the other two:

- ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 for effects from four to twelve weeks after onset, and

- post-COVID-19 syndrome for effects that persist 12 or more weeks after onset.

NICE describes the term long COVID, which it uses "in addition to the clinical case definitions", as "commonly used to describe signs and symptoms that continue or develop after acute COVID-19. It includes both ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 (from four to twelve weeks) and post-COVID-19 syndrome (12 weeks or more)".[21]

NICE defines post-COVID-19 syndrome as "Signs and symptoms that develop during or after an infection consistent with COVID‑19, continue for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis. It usually presents with clusters of symptoms, often overlapping, which can fluctuate and change over time and can affect any system in the body. Post‑COVID‑19 syndrome may be considered before 12 weeks while the possibility of an alternative underlying disease is also being assessed".[21]

American definition

In February 2021, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) director Francis Collins indicated long COVID symptoms for individuals who "don't recover fully over a period of a few weeks" be collectively referred to as "Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection" (PASC). The NIH listed long COVID symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, brain fog, sleep disorders, intermittent fevers, gastrointestinal symptoms, anxiety, and depression. Symptoms can persist for months and can range from mild to incapacitating, with new symptoms arising well after the time of infection.[22] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) term Post-Covid Conditions qualifies long Covid as symptoms four or more weeks after first infection.[4]

Symptoms

| External video | |

|---|---|

A multinational online survey with 3,762 adult participants with illness lasting more than 28 days found that recovery takes longer than 35 weeks for 91% of them. On average, participants experienced 56 symptoms (standard deviation ± 25.5) in nine organ systems. Symptoms varied over time, and the most common symptoms after six months were fatigue, post-exertional malaise and cognitive dysfunction.[25][26]

Symptom relapse occurred in 86% of adult participants triggered by physical or mental effort or by stress. Three groups of symptoms were identified: initial symptoms that peak in the first two to three weeks and then subside; stable symptoms; and symptoms that increase markedly in the first two months and then stabilize.[25]

Symptoms reported by adults with long COVID include:[27][28][29][30][31][7][32]

- Extreme fatigue

- Long-lasting cough

- Muscle weakness

- Low-grade fever

- Inability to concentrate (brain fog)

- Memory lapses

- Mental health problems, such as changes in mood or depression

- Sleep difficulties

- Headaches

- Joint pain

- Needle pains in arms and legs

- Diarrhoea

- Bouts of vomiting

- Loss of, or changes in, sense of taste

- Loss of, or changes in, sense of smell (parosmia[33] or anosmia)[33]

- Sore throat and or difficulties swallowing

- Blood disorders, including new onsets of diabetes and hypertension

- Heartburn (gastroesophageal reflux disease)

- Skin rash

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pains

- Palpitations

- Kidney problems (including, acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease)[34]

- Changes in oral health (teeth, saliva, gums)

- Tinnitus[35]

- Hearing loss[35]

- Blood clotting (including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism)

- Erectile dysfunction[36]

Epidemiology

Estimates of the prevalence of long COVID vary widely. The estimates depend on the definition of long COVID and the population studied. An April 2022 meta-analysis estimated that the pooled prevalence of post-COVID conditions was 43%, with estimates ranging between 9% and 81%. People who had been hospitalised with COVID saw a higher prevalence of 54%, while this number dropped to 34% for nonhospitalised people. Prevalence generally decreased with a longer follow-up time.[37] In people age 0–18 years the prevalence of long COVID conditions – like mood symptoms, CFS and sleep disorders – appears to be at ~25% overall.[38][39]

In a large population cohort study in Scotland, 42% of respondents said they had not fully recovered after 6 to 18 months after catching COVID, and 6% indicated they had not recovered at all. The risk of long COVID was associated with disease severity; people with asymptomatic infection did not have increased risk of long COVID symptoms compared to people who had never been infected. Those that had been hospitalised had 4.6 times higher odds of no recovery compared to nonhopitalised people.[40]

In June 2022, a CDC study based on electronic health records showed that "one in five COVID-19 survivors aged 18–64 years and one in four survivors aged ≥65 years experienced at least one incident condition that might be attributable to previous COVID-19" or long COVID.[41][42] An analysis of private healthcare claims showed that of 78,252 patients diagnosed with 'long COVID', 75.8% had not been hospitalized for COVID-19.[43][44]

Children

Long COVID is uncommon in children and their features differ from adults: In a retrospective cohort study from October 2022 of almost 660,000 US children tested for SARS-CoV-2 by antigen or polymerase chain reaction, the incidence of at least 1 systemic, syndromic, or medication feature of long COVID (1-6 months afterwards) was 42% among viral test–positive children versus 38% among viral test–negative children, that is there was an incidence proportion difference of only 3.7%. Long COVID was identified more in those cared for intensive care unit during the acute illness phase, children younger than 5 years, and those with complex chronic conditions. Neurological symptoms, such as headache, vertigo, and paresthesiae were not significant findings in this study, as opposed to in adults.[45]

A 2021 study from the UK Office for National Statistics with 20,000 participants, including children and adults, found that, in children who tested positive, at least one symptom persisted after five weeks in 9.8% of children aged two to eleven years and in 13% of children aged 12 to 16 years.[46] A 2022 University College London study in the UK, found that children ages 11–17 who had a positive PCR test were more likely to have three or more symptoms three months after their diagnosis compared to those with a negative test.[47]

Causes

It is currently unknown why most people recover fully within two to three weeks and others experience symptoms for weeks or months longer.[48] The exact processes that cause long COVID remain uncertain, but research has established that long COVID is associated with changes in fatty acid metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction.[49][50]

A number of mechanisms have been suggested.[26]

A March 2021 review article cited the following pathophysiological processes as the predominant causes of long COVID:[51]

- direct toxicity in virus infected tissue, especially the lungs

- ongoing inflammation due to post-infection immune system dysregulation

- vascular injury and ischemia caused by virus induced hypercoagulability (tendency to form internal clots) and thromboses (internal blood clots)

- impaired regulation of the renin-angiotensin system related to the effect of SARS-CoV-2 on ACE2 containing tissue

In October 2020, a review by the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Research hypothesized that ongoing long COVID symptoms may be due to four syndromes:[52][53]

- permanent damage to the lungs and heart,

- post-intensive care syndrome,

- Post-viral fatigue, sometimes regarded as the same as myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), and

- continuing COVID-19 symptoms.

Other situations that might cause new and ongoing symptoms to include:

- the virus being present for a longer time than usual, due to an ineffective immune response;[48]

- reinfection (e.g., with another strain of the virus);[48]

- damage caused by inflammation and a strong immune response to the infection;[48]

- post-traumatic stress or other mental sequelae,[48] especially in people who had previously experienced anxiety, depression, insomnia, or other mental health difficulties;[54]

- inhibited oxygen exchange as a result of persistent circulating blood plasma microclots;[55] and

- development of various autoantibodies after infection.[56][57][58]

Similarities to other syndromes

Long COVID is similar to post-Ebola syndrome and the post-infection syndromes seen in chikungunya and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), which is often triggered by infection and immune activation and was previously also known as "post-viral fatigue". The pathophysiology of long COVID may be similar to these other conditions.[18] Some long COVID patients in Canada have been diagnosed with ME/CFS, a "debilitating, multi-system neurological disease that is believed to be triggered by an infectious illness in the majority of cases". Lucinda Bateman, a US specialist in ME/CFS in Salt Lake City, believes that the two syndromes are identical. There is need for more research into ME/CFS; Anthony Fauci, chief medical adviser to the US government, said that COVID-19 is a "well-identified etiologic agent that should be very helpful now in getting us to be able to understand [ME/CFS]".[59]

Risk factors

Several risk factors have been found for long COVID:

- Gender – Women are more likely to develop long COVID than men.[37] Some research suggests this is due primarily to hormonal differences,[60][61] while other research points to other factors, including chromosomal genetics, sex-dependent differences in immune system behavior; non-biological factors may also be relevant.[18]

- Age, with older people more at risk[37][40]

- Obesity[37]

- Asthma[37]

- Depression or anxiety[40]

- The number of symptoms during acute COVID[37]

Diagnosis

Xenon MRI is being used to study long COVID, because it provides patients and physicians with explanations for previously unexplained observations. Xenon MRI can measure gas exchange and provide information on how much air is taken up by a patient's bloodstream, which is being researched in long-haul COVID patients.[62][63]

Xenon MRI can quantify three components of lung function: ventilation, barrier tissue uptake and gas exchange. Xenon-129 is soluble in pulmonary tissue, which allows the evaluation of lung functions such as perfusion and gas exchange (an advantage over helium). Ventilation measures how the air is distributed in the lung and can provide the locations of potentially compromised lung areas if no xenon reaches those areas. Barrier tissue uptake and gas exchange measure how much air diffuses across the alveolar-capillary membrane. Xenon MRI helps determine how well air is taken in by the lungs, absorbed into lung tissue, and taken up by the blood.[64][63]

Prevention

A September 2021 study published in The Lancet found that having two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine halved the odds of long COVID.[65] However, a May 2022 study published by Nature that examined VA Saint Louis Health Care System records from January to December 2021 of more than 13 million people, including 34,000 people vaccinated against COVID-19 who had breakthrough infections, found that COVID-19 vaccination reduced long COVID risk by about 15%.[66]

Treatment and management

As of May 2022, there is no established treatment for long COVID. There are however trials in progress for possible treatments.[67]

Management of long COVID depends on symptoms, and can often be done in primary care. Rest, planning and prioritising is advised for people with fatigue. People who suffer from post-exertional system exacarbation may benefit from activity management with pacing. People with allergic-type symptoms such as rashes on the skin may benefit from antihistamines.[68]

Health system responses

Australia

In October 2020, a guide published by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) says that ongoing post-COVID-19 infection symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath and chest pain will require management by GPs, in addition to the more severe conditions already documented.[69]

In December 2021, research by a health economics expert at Deakin University suggests that even without fully understanding the Omicron variant's effects yet, a further 10,000 to 133,000 long COVID cases are likely to emerge on top of the current approximately 9450 in New South Wales and 19,800 in Victoria, after border and other restrictions had been recently lifted. The RACGP released new guidelines for general practitioners to manage a large number of new long COVID patients.[70]

South Africa

In October 2020, the DATCOV Hospital Surveillance Department of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) looked into a partnership with the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) (an open-access research and data resource)[71] in order to conduct clinical research into the impact PASC may have within the South African context. As of 30 January 2021, the project has yet to receive ethical approval for the commencement of data collection. Ethics approval was granted on 3 February 2021 and formal data collection began on 8 February 2021.

United Kingdom

In Britain, the National Health Service set up specialist clinics for the treatment of long COVID.[72] The four Chief Medical Officers of the UK were warned of academic concern over long COVID on 21 September 2020 in a letter written by Trisha Greenhalgh published in The BMJ[73] signed by academics including David Hunter, Martin McKee, Susan Michie, Melinda Mills, Christina Pagel, Stephen Reicher, Gabriel Scally, Devi Sridhar, Charles Tannock, Yee Whye Teh, and Harry Burns, former CMO for Scotland.[73]

In October 2020, NHS England's head Simon Stevens announced the NHS had committed £10 million to be spent that year on setting up long COVID clinics to assess patients' physical, cognitive, and psychological conditions and to provide specialist treatment. Future clinical guidelines were announced, with further research on 10,000 patients planned and a designated task-force to be set up, along with an online rehabilitation service[74] – "Your Covid Recovery".[75] The clinics include a variety of medical professionals and therapists, with the aim of providing "joined-up care for physical and mental health".[76]

The National Institute for Health Research has allocated funding for research into the mechanisms behind symptoms of long COVID.[76][6]

In December 2020, University College London Hospitals (UCLH) opened a second long COVID clinic at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery for patients with post-COVID neurological issues. The first clinic had opened in May, primarily focused on respiratory problems, but both clinics refer patients to other specialists where needed, including cardiologists, physiotherapists and psychiatrists.[77] By March 2021 there were 69 long COVID clinics in the English NHS, mostly focussing on assessing patients, with more planned to open. There were fears that community rehabilitation services did not have capacity to manage large numbers of referrals.[78]

On 18 December 2020, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) published a guide to the management of long COVID.[79] The guideline was reviewed by representatives of the UK doctors #longcovid group, an online support group for COVID long-haulers, who said that it could be improved by introducing a more comprehensive description of the clinical features and physical nature of long COVID, among other changes.[80]

In November 2021 complaints were reported from NHS staff that neither their employers nor their trades unions were supportive, though the British Medical Association was pushing for long COVID to be classed as an occupational disease.[81]

In May 2022 demand for occupational therapy led rehabilitation services in Britain was reported to have increased by 82% over the previous six months as occupational therapists were supporting people whose needs have become more complex because of delays in treatment brought about by the pandemic. Half of occupational therapists surveyed were supporting people affected by lasting Covid symptoms.[82]

United States

On 23 February 2021, the National Institutes of Health director, Francis Collins, announced a major initiative to identify the causes and ultimately the means of prevention and treatment of people who have long COVID.[22] Part of this initiative includes the creation of the COVID-19 Project,[83] which will gather data on neurological symptoms associated with PASC.

On 28 April 2021, the Subcommittee on Health of the U.S. House of Representatives' Committee on Energy and Commerce held a hearing about long COVID.[84][85] In February 2022, it was announced that at least sixty-six hospitals and health systems had launched COVID recovery programs to aid patients who experience long term or lingering symptoms.[86]

Society and culture

Some people experiencing long COVID have formed groups on social media sites.[87][88][89][90] In many of these groups, individuals express frustration and their sense that their problems have been dismissed by medical professionals.[89][90] There is an active international long COVID patient advocacy movement.[91][92]

Founded by Lisa McCorkell and other scientists who are also long COVID patients, the Patient-Led Research Collaborative has carried out surveys to gather data on long COVID symptoms,[26][25] and has received funding for five long Covid research projects led by patients themselves.[26][93][94]

See also

- Chronic fatigue syndrome § Viral and other infections

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on neurological, psychological and other mental health outcomes – both acute and chronic neurological, psychiatric, olfactory, and mental health conditions

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children – pediatric comorbidity from COVID-19

- Post viral cerebellar ataxia – clumsy movement appearing a few weeks after a viral infection

- Post-Ebola virus syndrome – symptoms that persist after recovering from Ebola

- Post-polio syndrome – delayed reaction appearing years after acute polio infection resolves

References

- "A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV (April 2022). "A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 22 (4): e102–e107. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9. PMC 8691845. PMID 34951953.

- Baig AM (May 2021). "Chronic COVID syndrome: Need for an appropriate medical terminology for long-COVID and COVID long-haulers". Journal of Medical Virology. 93 (5): 2555–2556. doi:10.1002/jmv.26624. PMID 33095459.

- CDC (11 February 2020). "Post-COVID Conditions". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- "Overview | COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 | Guidance". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- "Researching long COVID: addressing a new global health challenge". NIHR Evidence. 12 May 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_50331. S2CID 249942230. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B (June 2021). "High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19". Nature. 594 (7862): 259–264. Bibcode:2021Natur.594..259A. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9. PMID 33887749.

- "Nearly half of people infected with COVID-19 experienced some 'long COVID' symptoms, study finds". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, Shi X, Fritsche LG, Mukherjee B (April 2022). "Global Prevalence of Post COVID-19 Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review". The Journal of Infectious Diseases: jiac136. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiac136. PMC 9047189. PMID 35429399.

- "COVID-19 and Your Health". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- Leviner S (September 2021). "Recognizing the Clinical Sequelae of COVID-19 in Adults: COVID-19 Long-Haulers". The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 17 (8): 946–949. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.05.003. PMC 8103144. PMID 33976591.

- Ledford H (June 2022). "How common is long COVID? Why studies give different answers". Nature. 606 (7916): 852–853. Bibcode:2022Natur.606..852L. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-01702-2. PMID 35725828. S2CID 249887289. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- "Center for Post-COVID Care | Mount Sinai – New York". Mount Sinai Health System. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- "Delhi's Post-Covid Clinic For Recovered Patients With Fresh Symptoms Opens". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Post COVID-19 Rehabilitation and Recovery". Lifemark. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Perego E, Callard F, Stras L, Melville-Johannesson B, Pope R, Alwan N (1 October 2020). "Why we need to keep using the patient made term 'Long Covid'". The BMJ. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Callard F, Perego E (January 2021). "How and why patients made Long Covid". Social Science & Medicine. 268: 113426. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426. PMC 7539940. PMID 33199035.

- Brodin P (January 2021). "Immune determinants of COVID-19 disease presentation and severity". Nature Medicine. 27 (1): 28–33. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-01202-8. PMID 33442016.

- Pearson C (14 March 2022). "We're Not Prepared For The Next Pandemic Phase: Dealing With Long COVID". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- Wu KJ (8 October 2021). "Nine Pandemic Words That Almost No One Gets Right". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 14 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- "Context | COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- "NIH launches new initiative to study 'Long COVID'". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 23 February 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- "Lingering Symptoms: Researchers Identify Over 50 Long-Term Effects of COVID-19". SciTechDaily. Houston Methodist. 1 September 2021. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, Sepulveda R, Rebolledo PA, Cuapio A, Villapol S (August 2021). "More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 16144. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1116144L. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8. PMC 8352980. PMID 34373540.

- Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y, et al. (August 2021). "Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact". EClinicalMedicine. 38: 101019. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. PMC 8280690. PMID 34308300.

- Broadfoot M (8 August 2022). "How long will it take to understand long Covid?". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-080422-1. Archived from the original on 26 August 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- "COVID-19 (coronavirus): Long-term effects". Mayo Clinic. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "What are the long-term health risks following COVID-19?". NewsGP. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). 24 June 2020. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Yelin D, Wirtheim E, Vetter P, Kalil AC, Bruchfeld J, Runold M, et al. (October 2020). "Long-term consequences of COVID-19: research needs". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 20 (10): 1115–1117. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30701-5. PMC 7462626. PMID 32888409.

- Chen S (10 January 2021). "Chinese study finds most patients show signs of 'long Covid' six months on". South China Morning Post. Beijing. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- Wudan Y (26 November 2020). "Their Teeth Fell Out. Was It Another Covid-19 Consequence?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Guynup S (29 December 2021). "Can COVID-19 alter your personality? Here's what brain research shows". Science. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Brewer K (28 January 2021). "Parosmia: 'Since I had Covid, food makes me want to vomit'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Bowe B, Xie Y, Xu E, Al-Aly Z (November 2021). "Kidney Outcomes in Long COVID". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 32 (11): 2851–2862. doi:10.1681/ASN.2021060734. PMC 8806085. PMID 34470828. S2CID 237389462.

- Jafari Z, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH (March 2022). "Hearing Loss, Tinnitus, and Dizziness in COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 49 (2): 184–195. doi:10.1017/cjn.2021.63. PMC 8267343. PMID 33843530.

- Rabin RC (5 May 2022). "Can Covid Lead to Impotence?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, Shi X, Fritsche LG, Mukherjee B (April 2022). "Global Prevalence of Post COVID-19 Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiac136. PMC 9047189. PMID 35429399.

- "The prevalence of long-COVID in children and adolescents". News-Medical.net. 27 June 2022. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Ayuzo Del Valle NC, Perelman C, Sepulveda R, Rebolledo PA, et al. (June 2022). "Long-COVID in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analyses". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 9950. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.9950L. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-13495-5. PMC 9226045. PMID 35739136.

- Hastie CE, Lowe DJ, McAuley A, Winter AJ, Mills NL, Black C, Scott JT, O'Donnell CA, Blane DN, Browne S, Ibbotson TR, Pell JP (October 2022). "Outcomes among confirmed cases and a matched comparison group in the Long-COVID in Scotland study". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 5663. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33415-5. PMC 9556711. PMID 36224173.

- Belluck P (25 May 2022). "More than 1 in 5 adult Covid survivors in the U.S. may develop long Covid, a C.D.C. study suggests". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- Bull-Otterson L (2022). "Post–COVID Conditions Among Adult COVID-19 Survivors Aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years – United States, March 2020–November 2021". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 71 (21): 713–717. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7121e1. ISSN 0149-2195. S2CID 249057133.

- Belluck P (18 May 2022). "Over 75 Percent of Long Covid Patients Were Not Hospitalized for Initial Illness, Study Finds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- "Patients Diagnosed with Post-COVID Conditions – An Analysis of Private Healthcare Claims Using the Official ICD-10 Diagnostic Code" (PDF). FAIR Health, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- Rao S, Lee GM, Razzaghi H, Lorman V, Mejias A, Pajor NM, et al. (October 2022). "Clinical Features and Burden of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children and Adolescents". JAMA Pediatrics. 176 (10): 1000–1009. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2800. PMC 9396470. PMID 35994282.

- "Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 1 April 2021". Office for National Statistics. 1 April 2021. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- "Long COVID and kids: more research is urgently needed". Nature. 602 (7896): 183. February 2022. Bibcode:2022Natur.602..183.. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00334-w. PMID 35136225. S2CID 246678864. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022.

- Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A'Court C, Buxton M, Husain L (August 2020). "Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care". BMJ. 370: m3026. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3026. PMID 32784198. S2CID 221097768.

- Guntur VP, Nemkov T, de Boer E, Mohning MP, Baraghoshi D, Cendali FI, et al. (26 October 2022). "Signatures of Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Impaired Fatty Acid Metabolism in Plasma of Patients with Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC)". Metabolites. 12 (11): 1026. doi:10.3390/metabo12111026. ISSN 2218-1989.

- de Boer E, Petrache I, Goldstein NM, Olin JT, Keith RC, Modena B, et al. (January 2022). "Decreased Fatty Acid Oxidation and Altered Lactate Production during Exercise in Patients with Post-acute COVID-19 Syndrome". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 205 (1): 126–129. doi:10.1164/rccm.202108-1903LE. PMC 8865580. PMID 34665688.

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, et al. (April 2021). "Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome". Nature Medicine. 27 (4): 601–615. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. PMC 8893149. PMID 33753937.

- "Living with Covid19. A dynamic review of the evidence around ongoing covid-19 symptoms (often called long covid)". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 15 October 2020. doi:10.3310/themedreview_41169. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2020.

- Mahase E (October 2020). "Long covid could be four different syndromes, review suggests". BMJ. 371: m3981. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3981. PMID 33055076. S2CID 222348080. Archived from the original on 26 December 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ (February 2021). "Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 8 (2): 130–140. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4. PMC 7820108. PMID 33181098.

- Pretorius E, Vlok M, Venter C, Bezuidenhout JA, Laubscher GJ, Steenkamp J, Kell DB (August 2021). "Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin". Cardiovascular Diabetology. 20 (1): 172. doi:10.1186/s12933-021-01359-7. PMC 8381139. PMID 34425843.

- Arthur JM, Forrest JC, Boehme KW, Kennedy JL, Owens S, Herzog C, et al. (3 September 2021). "Development of ACE2 autoantibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection". PloS One. 16 (9): e0257016. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1657016A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0257016. PMC 8415618. PMID 34478478.

- Wallukat G, Hohberger B, Wenzel K, Fürst J, Schulze-Rothe S, Wallukat A, et al. (16 April 2021). "Functional autoantibodies against G-protein coupled receptors in patients with persistent Long-COVID-19 symptoms". Journal of Translational Autoimmunity. 4: 100100. doi:10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100100. PMC 8049853. PMID 33880442.

- Bertin D, Kaphan E, Weber S, Babacci B, Arcani R, Faucher B, et al. (December 2021). "Persistent IgG anticardiolipin autoantibodies are associated with post-COVID syndrome". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 113: 23–25. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.079. PMC 8487460. PMID 34614444.

- Dunham J (5 May 2021). "Some COVID-19 long-haulers are developing a 'devastating' syndrome". CTV News. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- Pinna G (January 2021). "Sex and COVID-19: A Protective Role for Reproductive Steroids". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 32 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2020.11.004. PMC 7649655. PMID 33229187.

- Bjugstad K. "Sex Hormones May Be Key Weaponry in the Fight Against COVID-19". Endocrineweb. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- Crump E (14 June 2021). "Polarean: Durham company's lung imaging technique could help long-haul COVID patients". ABC11 Raleigh-Durham. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- Marshall H, Stewart NJ, Chan HF, Rao M, Norquay G, Wild JM (February 2021). "In vivo methods and applications of xenon-129 magnetic resonance". Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 122: 42–62. doi:10.1016/j.pnmrs.2020.11.002. PMC 7933823. PMID 33632417. S2CID 230595631.

- "Basic Principles of Hyperpolarized Gas". Polarean Imaging plc. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Merino J, Sudre CH, Molteni E, Berry S, et al. (January 2022). "Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 22 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00460-6. PMC 8409907. PMID 34480857.

- Reardon S (27 May 2022). "Long COVID Risk Falls Only Slightly after Vaccination". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- Ceban F, Leber A, Jawad MY, Yu M, Lui LM, Subramaniapillai M, et al. (July 2022). "Registered clinical trials investigating treatment of long COVID: a scoping review and recommendations for research". Infectious Diseases. 54 (7): 467–477. doi:10.1080/23744235.2022.2043560. PMC 8935463. PMID 35282780. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022.

- Greenhalgh T, Sivan M, Delaney B, Evans R, Milne R (September 2022). "Long covid-an update for primary care". BMJ. 378: e072117. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-072117. PMID 36137612. S2CID 252406968. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022.

- Fitzgerald B (14 October 2020). "Long-haul COVID-19 patients will need special treatment and extra support, according to new guide for GPs". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Crellin Z (17 December 2021). "Long COVID looms as Australia grapples with Omicron". The New Daily. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- "International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium". ISARIC. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- Cookson C (15 October 2020). "'Long Covid' symptoms can last for months". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Greenhalgh T (21 September 2020). "Covid-19: An open letter to the UK's chief medical officers". The BMJ. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "NHS to offer 'long covid' sufferers help at specialist centres". NHS England. 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "Your COVID Recovery". National Health Service. England. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Herman J (27 December 2020). "I'm a consultant in infectious diseases. 'Long Covid' is anything but a mild illness". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- "UCLH opens second 'long Covid' clinic for patients with neurological complications". University College London NHS Foundation Trust. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Brennan S (25 March 2021). "'No urgency, no plan' for long covid". Health Service Journal. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- "NICE, RCGP and SIGN publish guideline on managing the long-term effects of COVID-19". NICE. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Gorna R, MacDermott N, Rayner C, O'Hara M, Evans S, Agyen L, et al. (February 2021). "Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience". Lancet. 397 (10273): 455–457. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32705-7. PMC 7755576. PMID 33357467.

- Collins A (11 November 2021). "Unions guilty of a 'moral failure' in poor support for staff with long covid". Health Service Journal. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- Atkinson E (22 May 2022). "Fears of long-Covid crisis as demand for rehabilitation services surges". Independent. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "COVID-19 Neuro Databank-Biobank". NYU Langone Health. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- "The Long Haul: Forging a Path through the Lingering Effects of COVID-19". YouTube. 29 April 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- Smith CL (15 May 2021). "Here's What Happened When I Told Congress The Black And Ugly Truth About Long COVID". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- Carbajal E, Gleeson C (9 February 2022). "66 hospitals, health systems that have launched post-COVID-19 clinics". Beckers Hospital Review. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- "Long COVID Support Group". Facebook. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Blazonis S (27 November 2020). "Facebook Group Created by Tampa Man Aims to Connect COVID-19 Long Haulers". www.baynews9.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Witvliet MG (27 November 2020). "Here's how it feels when COVID-19 symptoms last for months". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Flynn G (25 January 2022). "Across Southeast Asia, Long COVID Haunts Pandemic Survivors". New Naratif. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Macnamara K. "The Covid 'longhaulers' behind a global patient movement". AFP. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Sifferlin A (11 November 2020). "How Covid-19 Long Haulers Created a Movement". Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Patient-Led Research Collaborative for Long COVID". Patient Led Research Collaborative. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Callard F, Perego E (January 2021). "How and why patients made Long Covid". Social Science & Medicine. 268: 113426. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426. PMC 7539940. PMID 33199035.

Further reading

General

- Long-term effects of coronavirus (long COVID) at UK National Health Service

- News from BBC News

Journal articles

- "Long COVID: let patients help define long-lasting COVID symptoms". Editorial. Nature. 586 (7828): 170. October 2020. Bibcode:2020Natur.586..170.. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02796-2. PMID 33029005. S2CID 222217022.

- Alwan NA (August 2020). "Track COVID-19 sickness, not just positive tests and deaths". Nature. 584 (7820): 170. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02335-z. PMID 32782377. S2CID 221107554.

- Kingstone T, Taylor AK, O'Donnell CA, Atherton H, Blane DN, Chew-Graham CA (December 2020). "Finding the 'right' GP: a qualitative study of the experiences of people with long-COVID". BJGP Open. Royal College of General Practitioners. 4 (5): bjgpopen20X101143. doi:10.3399/bjgpopen20X101143. PMC 7880173. PMID 33051223. S2CID 222351478.

- Nordvig AS, Fong KT, Willey JZ, Thakur KT, Boehme AK, Vargas WS, et al. (April 2021). "Potential Neurologic Manifestations of COVID-19". Neurology. Clinical Practice. 11 (2): e135–e146. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000897. PMC 8032406. PMID 33842082.

- Salisbury H (June 2020). "Helen Salisbury: When will we be well again?". BMJ. 369: m2490. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2490. PMID 32576550. S2CID 219983336.

- "Researching long COVID: addressing a new global health challenge". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). 12 May 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_50331. S2CID 249942230. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

External links

- Long Covid on YouTube (21 October 2020) – UK Government film about long COVID.

- Living with Covid19. A review of what is known about long COVID by the NIHR.

- "PHOSP". Home. University of Leicester.

The Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 study (PHOSP-COVID) is a consortium of leading researchers and clinicians from across the UK working together to understand and improve long-term health outcomes for patients who have been in hospital with confirmed or suspected COVID-19.

- RECOVER: Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (U.S. National Institutes of Health)