The President's Influence on US Foreign Policy

Presidents have more power and responsibility in foreign and defense policy than in domestic affairs. They are the commanders in chief of the armed forces; they decide how and when to wage war. As America' chief diplomat, the president has the power to make treaties to be approved by the Senate. And as head of state, the president speaks for the nation to other world leaders and receives ambassadors.

Presidents almost always point to foreign policy as evidence of their term's success. Domestic policy wonk Bill Clinton metamorphosed into a foreign policy enthusiast from 1993 to 2001. Even prior to 9/11, the notoriously untraveled George W. Bush underwent the same transformation. President Obama has been just as involved, if not more, in foreign policy than his predecessors. Congress—as long as it is consulted—is less inclined to challenge presidential initiatives in foreign policy than in domestic policy. The idea that the president has greater autonomy in foreign than domestic policy is known as the "Two Presidencies Thesis."

The President and Waging War

The President is the Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces and as such has broad authority over the armed forces. However, only Congress has authority to declare war and decide the civilian and military budget.

War powers provide a key avenue for presidents to act in foreign policy. After the 9/11 attacks, President Bush's Office of Legal Counsel argued that as commander in chief President Bush could do what was necessary to protect the American people. Since World War II, presidents have never asked Congress for (or received) a declaration of war. Instead, they relied on open-ended congressional authorizations to use force, United Nations resolutions, North American Treaty Organization (NATO) actions, and orchestrated requests from tiny international organizations like the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States.

Congress can react against undeclared wars by cutting funds for military interventions. Such efforts are time consuming and not in place until long after the initial incursion. Congress's most concerted effort to restrict presidential war powers, the War Powers Act, passed despite President Nixon's veto in 1973. It was established to limit presidential war powers, but it gave presidents the right to commit troops for sixty days with only the conditions being to consult with and report to Congress—conditions presidents often feel free to ignore. Since Vietnam, the act has done little to prevent presidents from unilaterally launching invasions.

President Obama did not seek congressional authorization before ordering the US military to join attacks on the Libyan air defenses and government forces in March 2011. After the bombing campaign started, Obama sent Congress a letter contending that as Commander-in-Chief he had constitutional authority for the attacks. White House lawyers used the distinction between "limited military operation" and "war" to justify this.

The President, Treaties, and Agreements

Article II, Section 2 of the United States Constitution grants power to the president to make treaties with the "advice and consent" of two-thirds of the Senate. This is different from normal legislation which requires approval by simple majorities in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. .

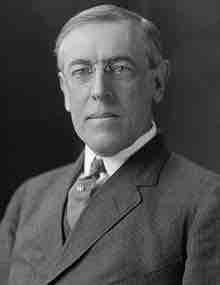

President Wilson

Wilson had disagreements with Congress over how the peace treaty ending World War I should be handled. Presidents often have a wide range of influence on US foreign policy.

Throughout U.S. history, the President has also made international "agreements" through congressional-executive agreements (CEAs) that are ratified with only a majority from both houses of Congress, or sole-executive agreements made by the President alone. The Supreme Court of the United States has considered congressional-executive and sole-executive agreements to be valid, and they have been common throughout American history.

The President and Diplomacy

Another section of the Constitution that gives the president power over foreign affairs is Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, known as the Appointments Clause. This clause empowers the President to appoint certain public officials with the "advice and consent" of the Senate. This clause also allows lower-level officials to be appointed without the advice and consent process. Thus, the President is responsible for the appointment of both upper- and lower-level diplomats and foreign-aid workers.

For example, the United States Secretary of State is the Foreign Minister of the United States and the primary conductor of state-to-state diplomacy. Both the Secretary of State and ambassadors are appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate .

Hillary Rodham Clinton

Hillary Clinton served as Secretary of State, which is the US's Foreign Minister. The President has the power to appoint diplomats (such as the Secretary of State), giving him or her substantial influence in US foreign policy.

As head of state, the President serves as the nation's top diplomat. Presidents are often depicted as speaking for and symbolically embodying the nation: giving a State of the Union address, welcoming foreign leaders, traveling abroad, or representing the United States at an international conference. All of these duties serve an important function in US foreign policy.