The Atlantic Slave Trade

The Atlantic slave trade took place across the Atlantic Ocean, predominantly from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The vast majority of slaves transported to the New World were Africans from the central and western parts of the continent, sold by African tribes to European slave traders who then transported them to the colonies in North and South America. Most contemporary historians estimate that between 9.4 and 12 million Africans arrived in the New World from the 16th through 19th centuries.

Various African tribes played a fundamental role in the slave trade by selling their captives or prisoners of war to European buyers, which was a common practice on the continent. The prisoners and captives who were sold to the Europeans were usually from neighboring or enemy ethnic groups; sometimes, African kings sold criminals into slavery as a form of punishment. The majority of African slaves, however, were foreign tribe members obtained from kidnappings, raids, or tribal wars.

The First Atlantic System

The First Atlantic System is a term used to characterized the Portuguese and Spanish African slave trade to the South American colonies in the 16th century—which lasted until 1580, when Portugal was temporarily united with Spain. While the Portuguese traded enslaved people themselves, the Spanish empire relied on the asiento system, awarding merchants (mostly from other countries) the license to trade enslaved people to their colonies. During the First Atlantic System, most of these traders were Portuguese, giving them a near-monopoly during the era, although some Dutch, English, and French traders also participated in the slave trade. After the union with Spain, Portugal was prohibited from directly engaging in the slave trade as a carrier and so ceded control over the trade to the Dutch, British, and French.

The Second Atlantic System

The Second Atlantic System, from the 17th through early 19th centuries, was the trade of enslaved Africans dominated by British, French, and Dutch merchants. Most Africans sold into slavery during the Second Atlantic System were sent to the Caribbean sugar islands as European nations developed economically slave-dependent colonies through sugar cultivation. It is estimated that more than half of the slave trade took place during the 18th century, with the British as the biggest transporters of slaves across the Atlantic. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, most of the international slave trade was abolished (although American slavery continued to exist well into the late 19th century).

Slavery in the Americas

European colonists in the Americas initially practiced systems of both bonded labor and indigenous slavery. However, for a variety of reasons, Africans replaced American Indians as the main population of enslaved people in the Americas. In some cases, such as on some of the Caribbean Islands, warfare and disease eliminated the indigenous populations completely. In other cases, such as in South Carolina, Virginia, and New England, the need for alliances with American Indian tribes, coupled with the availability of enslaved Africans at affordable prices, resulted in a shift away from American Indian slavery.

The resulting Atlantic slave trade was primarily shaped by the desire for cheap labor as the colonies attempted to produce raw goods for European consumption. Many American crops (including cotton, sugar, and rice) were not grown in Europe, and importing crops and goods from the New World often proved to be more profitable than producing them on the European mainland. However, a vast amount of labor was needed to create and sustain plantations that would be economically profitable. Western Africa (and later, Central Africa) became a prime source for Europeans to acquire enslaved peoples, to meet the desire for free labor in the American colonies, and to produce a steady supply of profitable cash crops.

Triangular Trade

The term triangular trade is used to characterize much of the Atlantic trading system from the 16th to early 19th centuries, in which three main commodity-types—labor, crops, and manufactured goods—were traded in three key Atlantic geographic regions.

Depiction of the classical model of the triangular trade

The triangular trade was a system in which slaves were transported to the Americas; sugar, tobacco, and cotton were exported to Europe; and textiles, rum, and manufactured goods were sent to Africa.

Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods which were traded for purchased or kidnapped Africans. These Africans were transported across the Atlantic as slaves and were then sold or traded in the Americas for raw materials. The raw materials would subsequently be transported back to Europe to complete the voyage.

A classic example would be the trade of sugar (often in its liquid form, molasses) from the Caribbean to Europe, where it was distilled into rum. The profits from the sale of sugar were then used to purchase manufactured goods, which were then shipped to West Africa where they were bartered for slaves. The slaves were then brought to the Caribbean to be sold to sugar planters. The profits from the sale of the slaves were then used to buy more sugar, which was shipped to Europe, and so on. This particular triangular trip took anywhere from five to 12 weeks and often resulted in massive fatalities of enslaved Africans on the Middle Passage voyage.

The Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the triangular trade where millions of enslaved people from Africa were shipped to the New World for sale. Voyages on the Middle Passage were a large financial undertaking generally organized by companies or groups of investors, rather than individuals. The duration of the transatlantic voyage varied widely, from one to six months depending on weather conditions. An estimated 15% of African slaves died during the Middle Passage; historians estimate that the total number of African deaths directly attributable to the Middle Passage voyage is approximately two million.

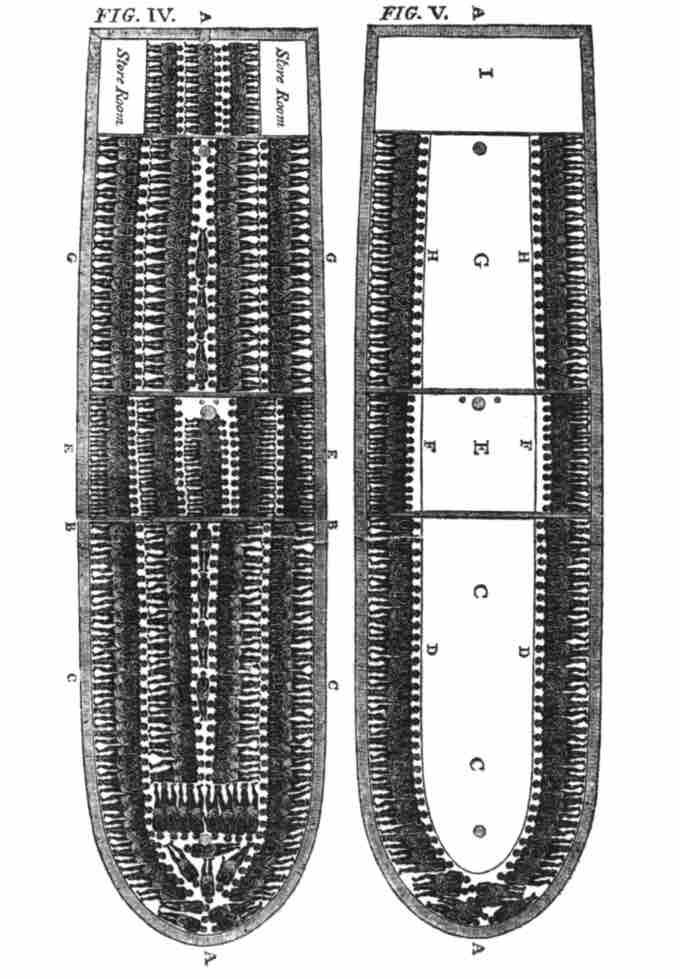

African kings, warlords, and private kidnappers sold captives to Europeans who held several coastal forts. The captives were usually force-marched to these ports along the western coast of Africa, where they were held for sale to the European slavers. Once sold to the European traders, African captives were brought to the slave ships for the voyage to the Americas. Typical slave ships contained several hundred slaves with approximately 30 crew members. Captives were normally chained together in pairs to save space and, at best, were fed one meal a day with water. Sometimes captives were allowed to move around during the day, but on most ships captives spent the entire journey crammed below decks.

During the Middle Passage voyage, disease (especially dysentery and scurvy) and starvation were the major killers. Furthermore, outbreaks of smallpox, syphilis, and measles were fatally contagious in close-quarter compartments. The rate of death increased with the length of the voyage as the quality and amount of food and water diminished. While the treatment of slaves on the Middle Passage varied by ship and voyage, it was often horrific. Captive Africans were considered by many Europeans to be less than human; they were instead seen as cargo or goods to be transported as cheaply and quickly as possible for trade. Corporal punishment was very common, with whippings used to punish melancholy or any form of resistance.

Slaves resisted in a variety of ways during the Middle Passage, usually by refusing to eat or committing suicide. In turn, crews and slave traders often force fed or tortured slaves and put nets on the sides of ships to keep slaves from attempting suicide. There are some recorded incidents of coordinated mass slave uprisings; however, most failed and were met with repercussions.

Slave ship

Diagram of a slave ship from the Atlantic slave trade. Slaves were chained together in incredibly close quarters, and overcrowding led to the spread of deadly diseases.