Operant conditioning is a theory of learning that focuses on changes in an individual's observable behaviors. In operant conditioning, new or continued behaviors are impacted by new or continued consequences. Research regarding this principle of learning first began in the late 19th century with Edward L. Thorndike, who established the law of effect.

Thorndike's Experiments

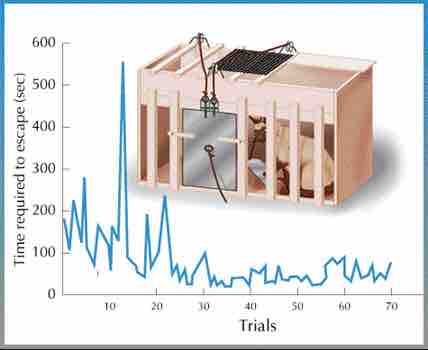

Thorndike's most famous work involved cats trying to navigate through various puzzle boxes. In this experiment, he placed hungry cats into homemade boxes and recorded the time it took for them to perform the necessary actions to escape and receive their food reward. Thorndike discovered that with successive trials, cats would learn from previous behavior, limit ineffective actions, and escape from the box more quickly. He observed that the cats seemed to learn, from an intricate trial and error process, which actions should be continued and which actions should be abandoned; a well-practiced cat could quickly remember and reuse actions that were successful in escaping to the food reward.

Thorndike's puzzle box

This image shows an example of Thorndike's puzzle box alongside a graph demonstrating the learning of a cat within the box. As the number of trials increased, the cats were able to escape more quickly by learning.

The Law of Effect

Thorndike realized not only that stimuli and responses were associated, but also that behavior could be modified by consequences. He used these findings to publish his now famous "law of effect" theory. According to the law of effect, behaviors that are followed by consequences that are satisfying to the organism are more likely to be repeated, and behaviors that are followed by unpleasant consequences are less likely to be repeated. Essentially, if an organism does something that brings about a desired result, the organism is more likely to do it again. If an organism does something that does not bring about a desired result, the organism is less likely to do it again.

Law of effect

Initially, cats displayed a variety of behaviors inside the box. Over successive trials, actions that were helpful in escaping the box and receiving the food reward were replicated and repeated at a higher rate.

Thorndike's law of effect now informs much of what we know about operant conditioning and behaviorism. According to this law, behaviors are modified by their consequences, and this basic stimulus-response relationship can be learned by the operant person or animal. Once the association between behavior and consequences is established, the response is reinforced, and the association holds the sole responsibility for the occurrence of that behavior. Thorndike posited that learning was merely a change in behavior as a result of a consequence, and that if an action brought a reward, it was stamped into the mind and available for recall later.

From a young age, we learn which actions are beneficial and which are detrimental through a trial and error process. For example, a young child is playing with her friend on the playground and playfully pushes her friend off the swingset. Her friend falls to the ground and begins to cry, and then refuses to play with her for the rest of the day. The child's actions (pushing her friend) are informed by their consequences (her friend refusing to play with her), and she learns not to repeat that action if she wants to continue playing with her friend.

The law of effect has been expanded to various forms of behavior modification. Because the law of effect is a key component of behaviorism, it does not include any reference to unobservable or internal states; instead, it relies solely on what can be observed in human behavior. While this theory does not account for the entirety of human behavior, it has been applied to nearly every sector of human life, but particularly in education and psychology.