Laveran and the Discovery of the Malaria Parasite

Alphonse Laveran was born in Paris on June 18, 1845. Like his father, he embraced the career of a military doctor. In 1874, at age 29, after a competitive examination ("aggrégation") he was appointed professor of military diseases and epidemics at the School of Military Medicine of Val-de-Grâce in Paris. While carrying out his duties in this position, he also acquired expertise in anatomic pathology. By age 34, he was already the author of a "Treatise on Military Diseases and Epidemics" and 62 other scientific communications.

In 1878, he was posted in Algeria (then a French territory), first at the military hospital in Bône, then in the military hospital in Constantine. Malaria was then a serious problem in the army, and this untiring worker meticulously studied the disease's clinical aspects and its anatomic pathology – providing, for example, an excellent histologic description of cerebral malaria. His ultimate objective was to identify the causal agent of the disease.

Dr. Alphonse Laveran, a military doctor in France's Service de Santé des Armées (Health Service of the Armed Forces).

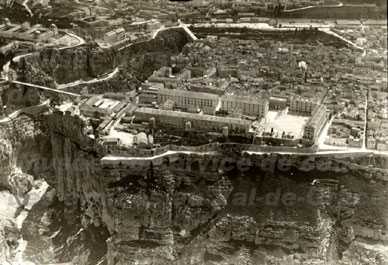

The military hospital in Constantine (Algeria), where Laveran discovered the malaria parasite in 1880. The hospital (long building in the front, closest to the cliff) was built by the French in 1841 (Algeria was then a French territory). In 1913, the hospital was named after Laveran. It closed in 1963.

Earlier theories were that malaria was caused by bad air ("mala aria" in Italian) from marshlands. However, following the discoveries of Louis Pasteur that most infectious diseases are caused by microbial germs (the "germ theory"), the hypothesis of a bacterial origin of malaria became increasingly attractive. As related in Laveran’s "Treatise On Marsh Fevers" (1884), numerous studies, mostly in Italy but also in the United States, had searched for an infectious agent in marshland soil and incriminated various algae, aquatic protozoa, and bacteria such as Bacillus malariae in Italy. (Protozoa are micro-organisms that are single-celled, with a well-defined nucleus, and without cell walls.)

Laveran, for his part, used observations from his work in anatomic pathology – deaths due to malaria were frequent – to guide his search for the causal agent of malaria. By studying the lesions in organs and in blood in two very different clinical situations, severe attacks and chronic malaria, Laveran found that the only constant element was the presence of granules of black pigment in the blood. These pigmented granules occurred at very different frequencies depending on the cases. Laveran concluded that these pigmented granules were specific to malaria, and that they originated in the blood. He patiently performed many examinations of freshly collected blood specimens, without the benefit of staining techniques (these were not yet available).

At the hospital in Bône, Laveran noticed spherical bodies, free or adherent to red blood cells. Some of these bodies were glassy ("hyaline") and difficult to see; others contained dark granules of pigment exhibiting ameboid movements. He also noticed pigmented bodies that were crescent shaped. He was able to clearly differentiate all these elements from pigment-carrying ("melaniferous") leukocytes, which had been known for 30 years (Risori, 1846).

But the revelation came at the military hospital in Constantine, in the early morning hours of November 6, 1880. Examining the blood of a patient who had been febrile for 15 days, he saw "…on the edges of a pigmented spherical body, filiform elements which move with great vivacity, displacing the neighboring red blood cells." By chance, but also thanks to his tenacity and patience, he had seen the exflagellation of a male gametocyte, a phase in the life cycle of malaria parasites which usually occurs in the stomach of the Anopheles mosquito. The motility of these elements immediately convinced Laveran that he had discovered the agent causing malaria and that it was a protozoan parasite. After observing these motile elements again, some adhering to the spherical bodies and others free, Laveran sent two notes to the Academy of Medicine, in November and December 1880 on this "New Parasite Found in the Blood of Several Patients Suffering from Marsh Fever."

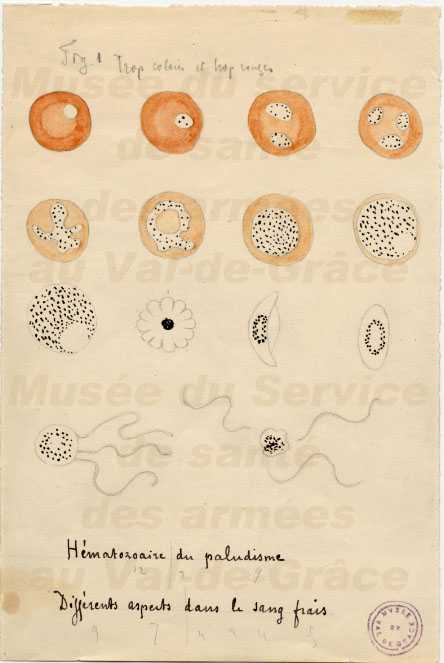

Illustration drawn by Laveran of various stages of malaria parasites as seen on fresh blood. Dark pigment granules are present in most stages. The bottom row shows an exflagellating male gametocyte, which produces "filiform elements which move with great vivacity."

During the following years, Laveran continued his work in Algeria. He also visited Italy in 1882, where he looked for the parasite in the air, the water, and the soil of marshlands. That search proved negative, making him suspect that the parasite could be in the body of mosquitoes, which were abundant in that environment. He put forward this hypothesis in his "Treatise on Marsh Fevers" of 1884 and defended it at the International Congress of Hygiene in Budapest (1894). In his 1891 treatise "On Malaria And Its Hematozoon," he wrote, without giving a reference, that "King, in America, had the idea that mosquitoes played a role in malaria."

Laveran’s publications were generally met with skepticism, especially among the Italians and the disciples of Louis Pasteur (except Elie Metchnikoff), who were in favor of a bacterial cause. Later, following his return in 1884 to the Val-de-Grâce School of Military Medicine, Laveran invited Pasteur to visit and see under his microscope the motile, flagellated bodies. Pasteur was immediately convinced (Roux, 1915). It was not until the years 1885-1890 that the parasitic origin of malaria was accepted.

Manuscript by Laveran (fragment), for a communication to the Medical Society of Hospitals (Société Médicale des Hôpitaux) on April 28, 1882.

Inauguration of the Laveran square. This square, in front of the church of the Val-de-Grâce military hospital in Paris, was named after Laveran on November 6, 1930.

After the development of stains with methylene blue (Ehrlich, 1899), doubt was not possible anymore, and the various species of malaria parasites were identified. (Laveran had until then been in favor of a single species.)

In 1884, Laveran left Algeria and returned to the Val-de-Grâce School of Military Medicine, where he was professor of military hygiene. He continued his research on malaria, both at the Val-de-Grâce Hospital and in the field in the Camargue (in southern France) and on the French island of Corsica. He left the Army in 1896 to work as a volunteer at the Pasteur Institute. There he devoted himself to the study of protozoal infections of animals and humans, especially trypanosomiasis. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1907 in recognition of his discovery of the malaria parasite and for his overall work on protozoa as causes of diseases. He gave the proceeds of his prize to the Pasteur Institute for the creation of a laboratory devoted to tropical diseases.

Laveran died in Paris on May 18, 1922. He was a patient and persistent observer, remarkable for the rigor with which he drew conclusions from observed facts. He wrote more than 600 scientific communications and 6 books. He was a solitary worker whose only interest was science, to which he dedicated 45 years of his life.

Text contributed by Prof. Guy Charmot, Service de Santé des Armées (Ret.) (Health Service of the Armed Forces), France.

Images contributed by the Service de Santé des Armées (Health Services of the Armed Forces), France.

The church of Val-de-Grâce (Paris) in 2004. The church dates from 1645. The Val-de-Grâce complex currently includes, in addition to the church, a military hospital, a military medical school, and a museum of military medicine.

- Page last reviewed: September 23, 2015

- Page last updated: September 23, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir