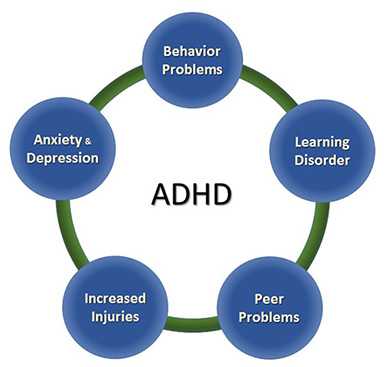

Other Concerns & Conditions

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) often occurs with other disorders. About half of children with ADHD referred to clinics have other disorders as well as ADHD.

The combination of ADHD with other disorders often presents extra challenges for children, parents, educators, and healthcare providers. Therefore, it is important for doctors to screen every child with ADHD for other disorders and problems. This page provides an overview of the more common conditions and concerns that can occur with ADHD. Talk with your doctor if you have concerns about your child’s symptoms.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends

Every child with ADHD should be screened for other disorders and problems.

Behavior or Conduct Problems

Children occasionally act angry or defiant around adults or respond aggressively when they are upset. When these behaviors persist over time, or are severe, they can become a behavior disorder. Children with ADHD are more likely to be diagnosed with a behavior disorder such as Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder. About 1 in 4 children with ADHD have a diagnosed behavior disorder1.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

When children act out persistently so that it causes serious problems at home, in school, or with peers, they may be diagnosed with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD). ODD is one of the most common disorders occurring with ADHD. ODD usually starts before 8 years of age, but can also occur in adolescents. Children with ODD may be most likely to act oppositional or defiant around people they know well, such as family members or a regular care provider. Children with ODD show these behaviors more often than other children their age.

Examples of ODD behaviors include

- Often losing their temper

- Arguing with adults or refusing to comply with adults’ rules or requests

- Often getting angry, being resentful, or wanting to hurt someone who they feel has hurt them or caused problems for them

- Deliberately annoying others; easily becoming annoyed with others

- Often blaming other people for their own mistakes or misbehavior

Conduct Disorder

Conduct Disorder (CD) is diagnosed when children show a behavioral pattern of aggression toward others, and serious violations of rules and social norms at home, in school, and with peers. These behaviors often lead to breaking the law and being jailed. Having ADHD makes a child more likely to be diagnosed with CD. Children with CD are more likely to get injured, and have difficulties getting along with peers.

Examples of CD behaviors include

- Breaking serious rules, such as running away, staying out at night when told not to, or skipping school

- Being aggressive in a way that causes harm, such as bullying, fighting, or being cruel to animals

- Lying and stealing, or damaging other people’s property on purpose

Treatment for disruptive behavior disorders

Starting treatment early is important. Treatment is most effective if it fits the needs of the child and family. The first step to treatment is to have a comprehensive evaluation by a mental health professional. Some of the signs of behavior problems, such as not following rules, are also signs of ADHD, so it is important to get a careful evaluation to see if a child has both conditions. For younger children, the treatment with the strongest evidence is behavioral parent training, where a therapist helps the parent learn effective ways to strengthen the parent-child relationship and respond to the child’s behavior. For school-age children and teens, an often-used effective treatment is combination training and therapy that includes the child, the family, and the school. Sometimes medication is part of the treatment.

Learning Disorder

Many children with ADHD also have a learning disorder (LD). This is in addition to other symptoms of ADHD, such as difficulties paying attention, staying on task, or being organized, which also keep a child from doing well in school.

Having a learning disorder means that a child has a clear difficulty in one or more areas of learning, even when their intelligence is not affected. Learning disorders include

- Dyslexia – difficulty with reading

- Dyscalculia – difficulty with math

- Dysgraphia – difficulty with writing

Data from the 2004-6 National Health Interview Survey suggests that almost half of children 6-17 years of age diagnosed with ADHD may also have LD2. The combination of problems caused by ADHD and LD can make it particularly hard for a child to succeed in school. Properly diagnosing each disorder is crucial, so that the child can get the right kind of help for each.

Treatment for learning disorders

Children with learning disorders often need extra help and instruction that is specialized for them. Having a learning disorder can qualify a child for special education services in school. Because children with ADHD often have difficulty in school, the first step is a careful evaluation to see if the problems are also caused by a learning disorder. Schools usually do their own testing to see if a child needs intervention. Parents, healthcare providers, and the school can work together to find the right referrals and treatment.

Learn more about learning and attention issues

Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety

Many children have fears and worries. However, when a child experiences so many fears and worries that they interfere with school, home, or play activities, it is an anxiety disorder. Children with ADHD are more likely than those without to develop an anxiety disorder. Almost 1 in 5 children with ADHD have a diagnosed anxiety disorder1.

Examples of anxiety disorders include

- Separation anxiety – being very afraid when they are away from family

- Social anxiety – being very afraid of school and other places where they may meet people

- General anxiety – being very worried about the future and about bad things happening to them

Depression

Occasionally being sad or feeling hopeless is a part of every child’s life. When children feel persistent sadness and hopelessness, it can cause problems. Children with ADHD are more likely than children without ADHD to develop childhood depression. Children may be more likely to feel hopeless and sad when they can’t control their ADHD symptoms and the symptoms interfere with doing well at school or getting along with family and friends. About 1 in 7 children with ADHD have a diagnosis of depression1.

Examples of behaviors often seen when children are depressed include

- Feeling sad or hopeless a lot of the time

- Not wanting to do things that are fun

- Having a hard time focusing

- Feeling worthless or useless

Children with ADHD already have a hard time focusing on things that are not very interesting to them. Depression can make it hard to focus on things that are normally fun. Changes in eating and sleeping habits can also be a sign of depression. For children with ADHD who take medication, changes in eating and sleeping can also be side-effects from the medication rather than signs of depression. Talk with your doctor if you have concerns.

Extreme depression can lead to thoughts of suicide. For youth ages 10-24 years, suicide is the leading form of death. Read more about suicide prevention.

Treatment for anxiety and depression

The first step to treatment is to talk with a healthcare provider to get an evaluation. Some signs of depression, like having a hard time focusing, are also signs of ADHD, so it is important to get a careful evaluation to see if a child has both conditions. A mental health professional can develop a therapy plan that works best for the child and family. Early treatment is important, and can include child therapy, family therapy, or a combination of both. The school can also be included in therapy programs. For very young children, involving parents in treatment is very important. Cognitive behavioral therapy is one form of therapy that is used to treat anxiety or depression, particularly in older children. It helps the child change negative thoughts into more positive, effective ways of thinking. Consultation with a health provider can help determine if medication should also be part of the treatment.

Learn about the FDA’s warning when using antidepressants with young people

Difficult Peer Relationships

ADHD can make peer relationships or friendships very difficult. Having friends is important to children’s well-being and may be very important to their long-term development.

Although some children with ADHD have no trouble getting along with other children, others have difficulty in their relationships with their peers; for example, they might not have close friends, or might even be rejected by other children. Children who have difficulty making friends might also more likely have anxiety, behavioral and mood disorders, substance abuse, or delinquency as teenagers.

- Parents of children with ADHD report that their child has almost 3 times as many peer problems as a child without ADHD.3

- Parents report that children with ADHD are almost 10 times as likely to have difficulties that interfere with friendships.3

How does ADHD interfere with peer relationships?

Exactly how ADHD contributes to social problems is not fully understood. Children who are inattentive sometimes seem shy or withdrawn to their peers. Children with symptoms of impulsivity/hyperactivity may be rejected by their peers because they are intrusive, may not wait their turn, or may act aggressively. In addition, children with ADHD are also more likely than those without ADHD to have other disorders that interfere with getting along with others.

Having ADHD does not mean a child won’t have friends.

Not everyone with ADHD has difficulty getting along with others. For those children who do have difficulty, many things can be done to help them with relationships. The earlier a child’s difficulties with peers are noticed, the more successful intervention may be. Although researchers don’t have definitive answers on what works best for children with ADHD, some things parents might consider as they help their child build and strengthen peer relationships are:

- Pay attention to how children get along with peers. These relationships can be just as important as grades to school success.

- Regularly talk with people who play important roles in your child’s life (such as teachers, school counselors, after-school activity leaders, healthcare providers, etc.). Keep updated on your child’s social development in community and school settings.

- Involve your child in activities with other children. Talk with other parents, sports coaches and other involved adults about any progress or problems that may develop with your child.

- Peer programs can be helpful, particularly for older children and teenagers. Social skills training alone has not shown to be effective, but peer programs where children practice getting along with others can help. Schools and communities often have such programs available. You may want to talk to your healthcare provider and someone at your child’s school about programs that might help.

Risk of Injuries

Children and adolescents with ADHD are likely to get hurt more often and more severely than peers without ADHD. Research indicates that children with ADHD are significantly more likely to

- Get injured while walking or riding a bicycle

- Have head injuries

- Injure more than one part of their body

- Be hospitalized for unintentional poisoning

- Be admitted to intensive care units or have an injury resulting in disability

More research is needed to understand why children with ADHD get injured, but it is likely that being inattentive and impulsive puts children at risk. For example, a young child with ADHD may not look for oncoming traffic while riding a bicycle or crossing the street, or may do something dangerous without thinking of the possible consequences. Teenagers with ADHD who drive are more likely to have problems with driving, including breaking traffic rules, getting traffic tickets, and being in a crash than drivers without ADHD4.

There are many ways to protect children from harm and keep them safe. Parents and other adults can take these steps to protect children with ADHD. Learn more about CDC’s Protect the Ones You Love initiative.

- Always have your child wear a helmet when riding a bike, skateboard, scooter, or skates. Remind children as often as necessary to watch for cars and to teach them how to be safe around traffic.

- Supervise children when they are involved in activities or in places where injuries are more likely, such as when climbing or when in or around a swimming pool.

- Keep potentially harmful household products, medications, and tools out of the reach of young children.

- Teens with ADHD are at extra risk when driving. They need to be extra careful to avoid distractions like driving with other teens in the car, talking on a cell phone, texting, eating, or playing with the radio. Like all teens, they need to avoid alcohol and drug use, and driving when drowsy.

- Parents should discuss rules of the road, why they are important to follow, and consequences for breaking them with their teens. Parents can create parent-teen driving agreements that put these rules in writing to set clear expectations and limits. Learn more about what parents can do from CDC’s Parents Are the Key campaign.

- For more injury prevention tips, visit CDC’s Injury Center.

References:

Larson, K., Russ, S. A., Kahn, R. S., & Halfon, N. (2011). Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics, 127(3), 462-470.

Pastor, P.N., & Reuben, C.A. (2008) Diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disability: United States, 2004–2006. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics, 10(237), 1-15.

Strine, T.W., Lesesne, C.A., Okoro, C.A., McGuire, L.C., Chapman, D.P., Balluz, L.S., & Mokdad, A.H. (2006). Emotional and behavioral difficulties and impairments in everyday functioning among children with a history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prevention of Chronic Disorders, 3(2):A52. Epub 2006 Mar 15.

Jerome, L., Segal, A., & Habinski, L. (2006). What we know about ADHD and driving risk: A literature review, meta-analysis and critique. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 15(3), 105-125.

- Page last reviewed: August 31, 2017

- Page last updated: August 31, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir