Lyme Disease

Agent

Borrelia burgdorferi

WHERE FOUND

WHERE FOUND

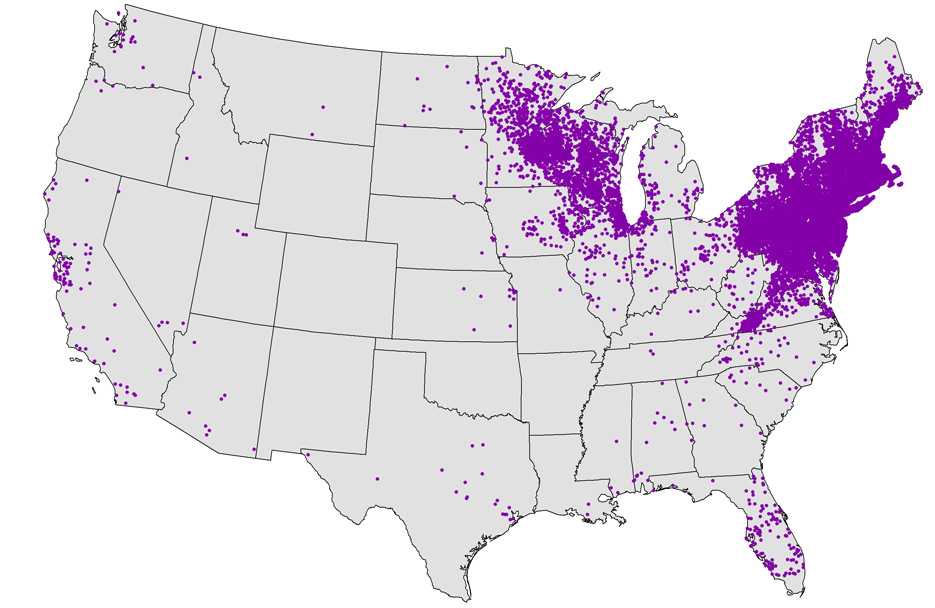

Lyme disease is most frequently reported from the upper midwestern and northeastern U.S. Some cases are also reported in northern California, Oregon, and Washington. In 2013, 95% of Lyme disease cases were reported from 14 states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

INCUBATION PERIOD: 3-30 days

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Localized Stage†

- Erythema migrans (EM)—red ring-like or homogenous expanding rash; classic rash not present in all cases.

- Flu-like symptoms – malaise, headache, fever, myalgia, arthralgia

- Lymphadenopathy

Disseminated Stage

- Multiple secondary annular rashes

- Flu-like symptoms

- Lymphadenopathy

Rheumatologic Manifestations

- Transient, migratory arthritis and effusion in one or multiple joints

- Migratory pain in tendons, bursae, muscle, and bones

- Baker’s cyst

- If untreated, arthritis may recur in same or different joints

Cardiac Manifestations

- Conduction abnormalities, e.g. atrioventricular node block

- Myocarditis, pericarditis

Neurologic Manifestations

- Facial palsy or other cranial neuropathy

- Meningitis

- Motor and sensory radiculoneuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex

- Subtle cognitive difficulties

- Encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, subtle encephalopathy, pseudotumor cerebri (all rare)

Additional Manifestations

- Conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis

- Mild hepatitis

- Splenomegaly

†During the localized (early) stage of illness, Lyme disease may be diagnosed clinically in patients who present with an EM rash. Serologic tests may be insensitive at this stage. During disseminated disease, however, serologic tests are usually positive.

GENERAL LABORATORY FINDINGS

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Mildly elevated hepatic transaminases

- Microscopic hematuria or proteinuria

- In Lyme meningitis, CSF typically shows lymphocytic pleocytosis, slightly elevated protein, and normal glucose.

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

- Demonstration of diagnostic IgM or IgG antibodies in serum. A two-tier testing protocol is recommended—EIA or IFA should be performed first; if positive or equivocal it is followed by a Western blot.

- Isolation of organism from a clinical specimen.

- In suspected Lyme meningitis, testing for intrathecal IgM or IgG antibodies may be helpful.

NOTES ON SEROLOGIC TESTS FOR LYME DISEASE

- Serologic tests are insensitive during the first few weeks of infection. During this stage, patients with an EM rash may be diagnosed clinically. While not necessary, acute and convalescent titers may be helpful in some cases.

- In persons with illness > 1 month, only IgG testing should be performed (not IgM). A positive IgM test alone is not sufficient to diagnose current disease.

- Due to antibody persistence, single positive serologic test results cannot distinguish between active and past infection.

- Serologic tests cannot be used to measure treatment response.

- Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and immunofluorescence assay (IFA) tests have low specificity and may yield false-positive results. They may cross-react with antibodies to commensal or pathogenic spirochetes, some viral infections (e.g., varicella, Epstein-Barr virus), or certain autoimmune diseases (e.g., lupus).

LYME DISEASE OR STARI?

An erythema migrans-like rash has also been described in humans following bites of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum. This condition has been named Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness (STARI). Although the rash may be accompanied by flu-like symptoms, long-term sequelae have not been reported. Because the cause of STARI is unknown, diagnostic blood tests are not available.

Lone star ticks can be found from central Texas and Oklahoma eastward across the southern states and along the Atlantic coast as far north as Maine.

It is not known whether antibiotic treatment is necessary or beneficial for patients with STARI. Nevertheless, because STARI resembles early Lyme disease, physicians often treat patients with the same antibiotics recommended for Lyme disease.

NOTE: Coinfection with B. microti and/or A. phagocytophilum should be considered in patients who present with initial symptoms that are more severe than are commonly observed with Lyme disease alone, especially in those who have high-grade fever for more than 48 hours despite appropriate antibiotic therapy or who have unexplained leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or anemia. Coinfection might also be considered in patients whose erythema migrans skin lesion has resolved but have persistent flu-like symptoms.

Treatment

Treatment regimens listed in the following table are for localized (early) Lyme disease. Treatment guidelines for patients with disseminated (late) Lyme disease are outlined in the reference below.†

These regimens are guidelines only and may need to be adjusted depending on a patient’s age, medical history, underlying health conditions, pregnancy status or allergies. Consult an infectious disease specialist for the most current treatment guidelines or for individual patient treatment decisions.

| Age Category | Drug | Dosage | Maximum | Duration, Days(Range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Doxycycline | 100 mg, twice per day orally | N/A | 14 (14-21) |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 500 mg, twice per day orally | N/A | 14 (14-21) | |

| Amoxicillin | 500 mg, three times per day orally | N/A | 14 (14-21) | |

| Children | Amoxicillin | 50 mg/kg per day orally, divided into 3 doses | 500 mg per dose | 14 (14-21) |

| Doxycycline | 4 mg/kg per day orally, divided into 2 doses | 100 mg per dose | 14 (14-21) | |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 30 mg/kg per day orally, divided into 2 doses | 500 mg per dose | 14 (14-21) |

NOTE: For patients intolerant of amoxicillin, doxycycline, and cefuroxime axetil, the macrolides azithromycin, clarithromycin, or erythromycin may be used, although they have a lower efficacy. Patients treated with macrolides should be closely observed to ensure resolution of clinical manifestations

References

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wang G, Schwartz I, Wormser GP. Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005;18(3):484-509.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Lyme disease (Lyme borreliosis, Borrelia burgdorferi infection). In: Pickering LK, Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012:474–479.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: caution regarding testing for Lyme disease. MMWR 2005; 54:125–126.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the second national conference on serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR 1995;44:590–591.

Halperin JJ, Baker P, Wormser GP. Common misconceptions about Lyme disease. Am J Med 2013;126(3):264.

Marques A. Lyme Disease: A Review. Curr Allergy Asthma Resp 2010, 10: 13-20.

Smith RP, Schoen RT, Rahn DW, Sikand VK, Nowakowski J, Parenti DL, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of early Lyme disease in patients with microbiologically confirmed erythema migrans. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:421–8.

Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 2012;379(9814):461-73.

Steere AC. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme Disease, Lyme borreliosis). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone; 2005;2798–2809.

Three Sudden Cardiac Deaths Associated with Lyme Carditis — United States, November 2012–July 2013. MMWR Dec 13;62(49):993-6.

†Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:1089–1134.

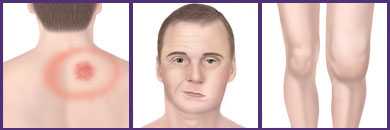

The erythema migrans (EM) rash occurs in 70–80% of patients with Lyme disease. EM rashes expand slowly over a few days after which they may develop a “bull’s-eye” appearance consisting of a red ring with central clearing. However, EM may take alternate forms—solid lesions, blue-purple hues, and crusted or blistering lesions have all been documented. The rash is not painful or pruritic, but it may be warm to the touch. If early localized Lyme disease is not treated, patients may develop multiple secondary circular rashes as spirochetes disseminate throughout the body.

Classic EM—Circular red rash with central clearing that slowly expands (Photo courtesy of Taryn Holman)

Bluish hue without central clearing (Photo courtesy of Yevgeniy Balagula)

Red, expanding lesion with central crust (Photo courtesy of Bernard Cohen)

Red, oval-shaped plaque on trunk (Photo courtesy of Alison Young)

Red-blue lesion with central clearing on back of knee (Photo courtesy of Robin Stevenson)

Early disseminated Lyme disease—multiple red lesions with dusky centers (Photo courtesy of Bernard Cohen)

Tick bite with mild allergic reaction. Not an erythema migrans. Allergic reactions typically appear within the first 48 hours of tick attachment and are usually <5 cm in diameter.

Reported Cases of Lyme Disease, U.S., 2015

NOTE: Each dot represents one case. Cases are reported from the infected person’s county of residence, not necessarily the place where they were infected.

NOTE: In 2015, no cases of Lyme disease were reported from Hawaii; 1 case of confirmed Lyme disease was reported from Alaska.

- Page last reviewed: October 23, 2014

- Page last updated: February 8, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir