Interim Guidance for Healthcare Workers Providing Care in West African Countries Affected by the Ebola Outbreak: Limiting Heat Burden While Wearing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Page Summary

Who this is for: Healthcare workers responding to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

What this is for: Recommendations for healthcare workers on how to limit heat burden and prevent heat-related illnesses while wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) during treatment of patients with Ebola virus disease (EVD).

How to use: Use this document to develop actions that healthcare workers can take to reduce the risk of heat-related illness.

Key Points

- Let healthcare workers know how wearing PPE places them at higher risk for a heat-related illness.

- Ensure that healthcare workers follow an acclimatization schedule by gradually increasing their time spent wearing PPE in a hot environment.

- Help healthcare workers stay well hydrated, watch for signs and symptoms of heat-related illnesses in themselves and their coworkers, and take time to rest and cool down.

- Create an environment in which healthcare workers are able to keep well hydrated, are monitored for signs and symptoms of heat-related illnesses, and can have proper rest breaks.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) reduces or eliminates exposure to hazardous chemicals, physical hazards, and disease-causing organisms such as the Ebola. virus The recommended PPE healthcare workers wear in Ebola treatment areas—waterproof apron, surgical gown, surgical cap, respirator, face shield, boots, and two layers of gloves—significantly reduces the body’s normal way of getting rid of heat by sweating. PPE holds excess heat and moisture inside, making the worker’s body even hotter. In addition, the increased physical effort to perform duties while carrying the extra weight of PPE can cause the healthcare worker to get hotter faster. Wearing PPE increases the risk for heat-related illnesses.

According to recent preliminary studies by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), wearing certain types of PPE can increase core body temperature more quickly than wearing other types of PPE in the same environment. When developing work/rest cycles, the type of PPE—along with the time an individual can wear the PPE—should be considered to avoid putting workers at risk for a heat-related illness. Other factors to consider include an individual’s actual work rate, fitness level, hydration level, and acclimatization. Data will be made available indicating times an individual can wear a certain type of PPE and not be at risk for a heat-related illness while working in West Africa.

Harsh conditions in EVD patient treatment and staff areas make heat issues greater, including

- Length of work shift: Shorter work shifts are better for healthcare workers who work in hot, humid places. However, shorter work shifts may not be possible where supplies of PPE are limited. Large workloads and a limited number of healthcare workers can also affect shift length.

- Limited electrical power: Air-conditioning and fans may not be available to cool healthcare workers during breaks. Healthcare workers need to have a shaded area in which to rest.

- Access to electrolyte replacement fluids is limited: Most healthcare workers have only bottled water to drink. However, if they sweat heavily, electrolyte replacement fluids are recommended.

- Other illnesses: Healthcare workers may become ill by consuming contaminated food or water. These illnesses can cause severe vomiting and diarrhea, which can lead to fluid loss and dehydration, increasing the risk for developing a heat-related illness.

- Limited or no medical oversight for healthcare workers while in the rest area: Often only a nonmedical person is available to monitor rest breaks and supplies.

- Limited number of healthcare workers: Understaffing means that new, potentially unacclimatized workers get only 2 days to adjust to working in a hot, humid environment before they start working with patients. Usually, they start wearing PPE on the second work day.

Other risk factors for heat-related illnesses include

- high temperatures and humidity

- direct sun or indoor heat sources such as flood lights or mechanical equipment

- limited air movement

- dehydration

- physical exertion

- current or pre-existing medical conditions (diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, obesity)

- certain medications

- pregnancy

- not being acclimatized (physiologically adjusted to the environment)

- age (60+)

- having a previous heat-related illness

Prescreening healthcare workers for medical conditions, medication use, history of heat illness, and other risk factors can decrease their risk of developing a heat-related illness. Encouraging prescreening and self-assessments of healthcare workers may ensure these workers take additional precautions in hot working conditions.

Heat-related Illnesses

Heat-related illnesses vary in severity and symptoms. The most severe form is heat stroke, which is a medical emergency and can be fatal if not immediately treated. Changes in cognitive function, such as confusion, slurred speech, and an inability to perform tasks may be the first noticeable signs of heat stroke. Confusion or cognitive impairment may affect the proper removal of the PPE and increase the risk of potential exposures to blood or body fluids. In addition, rhabdomyolysis, which is the breakdown of skeletal muscle, may be a consequence of heat stroke. Rhabdomyolysis can also be fatal if it causes seizures, irregular heart rhythms, and kidney failure. See Appendix A: Types of Heat-related Illness for detailed descriptions of the various types of heat-related illnesses, their symptoms, and first aid.

Monitoring Temperatures and Humidity

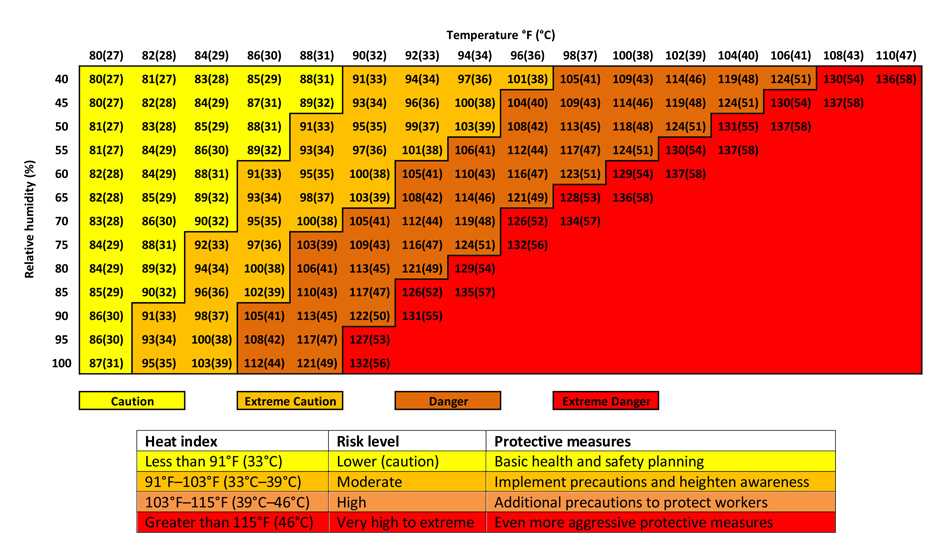

Although temperatures in West Africa may be stable day to day, it is important to monitor temperature and humidity, especially as the rainy season approaches. Healthcare workers should be aware that as the heat index increases, they may need more frequent rest breaks and increased water and/or electrolyte replacement fluids. The heat index is a measure of how hot it feels when humidity is taken into account with air temperature. Download the OSHA Heat Safety Tool or use the heat index table in Appendix B for information that may help assess heat conditions and their effects on healthcare workers.

Acclimatization

Acclimatization results in beneficial physiologic adaptations (increased sweating efficiency and stabilization of circulation), after gradually increased exposure to a hot environment. Workers who are not properly acclimatized before beginning their work are at increased risk for heat-related illnesses. It is important to develop work schedules that will help workers new to the environment and workers with previous work experience with the job adjust to their hot environment.

Recommendations

To reduce the risk of heat-related illnesses, healthcare workers who wear PPE should do the following in collaboration with site coordinators:

- Take time to acclimatize (adjust to the climate)

- Increase work exposure time in hot environmental conditions gradually over a 7- to 14-day period. If this is not possible, workers new to the climate should work shorter shifts until their bodies adjust to the heat.

- Schedule workers new to the climate no more than 20% of the usual work shift on day 1 with no more than a 20% increase on each additional day.

- Schedule workers with previous experience on the job in this climate no more than 50% of the usual work shift on day 1, 60% on day 2, 80% on day 3, and 100% on day 4.

- Stay well hydrated

- Arrive for your shift well hydrated. Be sure to drink plenty of fluids during your time away from work.

- Drink often enough that you do not feel thirsty. By the time you feel thirsty you are already dehydrated.

- Rehydrate during every rest break.

- Keep water and electrolyte replacement fluids or oral rehydration salts available in the rest area.

- Keep a weight scale at the rest area.

- Weigh yourself before putting on PPE at the beginning of your shift and after removing it and sweat-soaked scrubs on the last work shift of the day.

- Record your body weight changes so you stay aware of water loss during your work shift.

- Alert your supervisor if you have lost body weight during a shift. If more than 2% body weight is lost during the shift, heat tolerance decreases, and heart rate and body temperature increase. For example, for a starting weight of 150 lbs., a 2% loss would be 3 lbs. (150 lbs. × 0.02 = 3 lbs.)

- Tell your supervisor and do not start your shift if you have recently vomited or had diarrhea. If you have vomited or had diarrhea, you are already significantly dehydrated and may get others sick. Follow the return-to-work policy.

- Do not use caffeine, alcohol, and other stimulants.

- Watch for signs and symptoms of heat-related illnesses

- Avoid working alone. Ensure the site coordinator designates a buddy for each healthcare worker during the shift.

- Buddies can look for early signs of heat-related illness.

- Ask your buddy how he or she feels periodically, and encourage rest and water breaks as needed.

- Immediately tell your buddy if you do not feel well. He or she should go with you as you leave the hot area.

- Follow emergency procedures appropriate for your worksite if you see a coworker with heat-related symptoms or if someone faints.

- Assign a rest area monitor who is trained to detect symptoms of heat-related illness and knows basic first aid and cooling measures. Additional monitor duties may include

- Doing a quick mental health assessment as workers enter the rest area and before they leave. This may include asking them to answer basic questions like name and date. Slurred speech may be a sign of heat-related illness.

- Using an infrared thermometer to quickly assess aural (ear canal) temperature at the beginning of each break. Workers with normal mental status should not return to work if they have a temperature ≥ 102°F (39°C). Return to work only after temperature decreases to 100.4°F (38°C).

- Telling workers when it is time for their break. The monitor may have to do this via radio communication, visual signals such as a gesture that can be seen from the work area, or by asking workers to carry a message as they return to their shift. A work/rest cycle based on the environmental conditions and work tasks should provide guidance for when rest breaks are required. Rest break times do not include the time it takes to put on and remove PPE.

- Making sure that the rest area is well stocked with water and electrolyte replacement fluids or oral rehydration salts and that cooling devices work properly.

- Avoid working alone. Ensure the site coordinator designates a buddy for each healthcare worker during the shift.

- Take time to rest and cool down

- The rest area should be set up and maintained by the site coordinator and include

- Shaded area with chairs and cots

- Electric fans with misters if available or misting devices such as squirt bottles

- Bottled water and electrolyte replacement fluids or oral rehydration salts

- Basic first aid equipment, bucket with cool water to quickly cool down a person showing signs of heat exhaustion/stroke, and spare communication equipment to call for evacuation of workers if needed

- Follow all local emergency plans and procedures if workers must be evacuated from the area for additional treatment

- Keep several changes of scrubs in the rest area so workers can change out of scrubs wet with sweat

- Arrive for your shift well rested after an appropriate amount of sleep

- The rest area should be set up and maintained by the site coordinator and include

Additional Resources

OSHA-NIOSH INFOSHEET: Protecting Workers from Heat Illness

NIOSH Fast Facts: Protecting Yourself from Heat Stress [PDF – 2 pages]

References

Cervellin G, Comelli I, Lippi G [2010]. Rhabdomyolysis: historical background, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic features. Clin Chem Lab Med 48(6):749–756.

Golden JS, Hartz D, Brazel A, Luber G, Phelan P [2008]. A biometeorology study of climate and heat-related morbidity in Phoenix from 2001 to 2006. Int J Biometeorol 52(6):471–480.

Greenleaf JE, Harrison MH [1986]. Water and electrolytes. Acs Symposium Series 294:107–124.

Huggins R, Glaviano N, Negishi N, Casa DJ, Hertel J [2012]. Comparison of rectal and aural core body temperature thermometry in hyperthermic, exercising individuals: a meta-analysis. J Athl Train 47(3):329–338.

Kenny GP, Yardley J, Brown C, Sigal RJ, Jay O [2010]. Heat stress in older individuals and patients with common chronic diseases. CMAJ 182(10):1053–1060.

Khan FY [2009]. Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. Neth J Med 67(9):272–283.

NIOSH [1986]. Criteria for a recommended standard: occupational exposure to hot environments – revised criteria. By Henschel A, Dukes-Dobos FN, Kelmme J, Leidel NA. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 86-113.

National Oceanic and Atomospheric Administration [2012]. Heat: a major killer. [http://www.nws.noaa.gov/os/heat/index.shtml].Date accessed: September 2014.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration [2012]. Using the heat index: a guide for employers. [http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/heatillness/heat_index/using_heat_protect_workers.html]. Date accessed: September 2014.

Department of the Army and Air Force [2003]. Heat stress control and heat casualty management. Technical Bulletin, Medical 507. Air Force pamphlet 48-152 (I). [http://armypubs.army.mil/med/dr_pubs/dr_a/pdf/tbmed507.pdf]. Date accessed: September 2014.

APPENDIX A

Types of Heat-related Illnesses

| Type of Heat-related Illness | Symptoms | First Aid |

|---|---|---|

| Heat stroke |

Confusion; loss of consciousness; hot, dry skin or profuse sweating; seizures; very high body temperature Heat stoke may be fatal if treatment is delayed. |

|

| Rhabdomyolysis |

Muscle cramps/pain; abnormally dark colored urine the color of tea or cola; weakness; exercise intolerance–the person is physically unable to complete tasks he or she could previously do |

|

| Heat exhaustion |

Headache; nausea; dizziness; weakness; irritability; thirst; heavy sweating; elevated body temperature; decreased urine output |

|

| Heat cramps |

Muscle cramps, pain, or spasms in the abdomen, arms, or legs |

|

| Heat syncope |

Fainting; dizziness; lightheadedness during prolonged standing or suddenly rising from a sitting or lying position |

|

| Heat rash |

Looks like red cluster of pimples or small blisters that usually appears on the neck, upper chest, groin, under the breasts, and in elbow creases |

|

APPENDIX B

- Page last reviewed: January 29, 2015

- Page last updated: January 29, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir