Disulfiram

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Antabuse, Antabus, others |

| Other names | tetraethyldisulfanedicarbothioamide; 1-(Diethylthiocarbamoyldisulfanyl)-N,N-diethyl-methanethioamide |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Onset of action | Within 12 hours[1] |

| Duration of action | Up to 14 days[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682602 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Metabolism | Liver to diethylthiocarbamate |

| Elimination half-life | 60–120 hours |

| Chemical and physical data | |

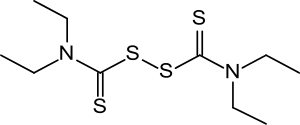

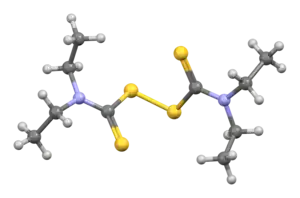

| Formula | C10H20N2S4 |

| Molar mass | 296.52 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Disulfiram, sold under the trade name Antabuse among others, is a medications used treat alcoholism by producing an acute sensitivity to alcohol.[1] It should be used in conjunction with counseling and support.[1] It is less preferred than acamprosate and naltrexone.[2] People should be informed regarding how it works before it is given.[1] It is taken once a day by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include liver problems, rash, sleepiness, sexual dysfunction, headache, and taste changes.[1] Other side effects include nerve problems and confusion.[1] If people drink alcohol well taking the medication skin flushing, headache, shortness of breath, and vomiting may occur.[1] In severe cases heart failure, seizures, or death may occur.[3] Use is not recommended in early pregnancy or when breastfeeding.[2] It works by altering the breakdown of alcohol in the body.[1]

Disulfiram was approved for medical use in the United States in 1951.[1] It is available as a generic medication.[2] In the United Kingdom 50 doses of 200 mg cost the NHS about 110 pounds as of 2020.[2] In the United States 60 doses of 250 mg costs as little as 42 USD as of 2020.[4] While implantable forms of disulfiram were studied to try to improve compliance these were found to be poorly effective.[5]

Medical uses

Alcohol dependence

Disulfiram is used as a second line treatment, behind acamprosate and naltrexone, for alcohol dependence.[6]

Disulfiram should not be taken if alcohol has been consumed in the last 12 hours.[7] There is no tolerance to disulfiram: the longer it is taken, the stronger its effects.[3] As disulfiram is absorbed slowly through the digestive tract and eliminated slowly by the body, the effects may last for up to two weeks after the initial intake; consequently, medical ethics dictate that patients must be fully informed about the disulfiram-alcohol reaction.[8]

Disulfiram does not reduce alcohol cravings, so a major problem is poor compliance. Methods to improve compliance include subdermal implants, which release the medication continuously over a period of up to 12 weeks, and supervised administration, for example, having the drug regularly administered by one's spouse.

Dosage

The typically dose is 200 mg to 500 mg per day.[2]

Side effects

The most common side effects in the absence of alcohol are headache, and a metallic or garlic taste in the mouth, though more severe side effects may occur.[9] Tryptophol, a chemical compound that induces sleep in humans, is formed in the liver after disulfiram treatment.[10] Less common side effects include decrease in libido, liver problems, skin rash, and nerve inflammation.[11] Liver toxicity is an uncommon but potentially serious side effect, and risk groups e.g. those with already impaired liver function should be monitored closely. That said, the rate of disulfiram-induced hepatitis are estimated to be in between 1 per 25,000 to 1 in 30,000,[12] and rarely the primary cause for treatment cessation.

Cases of disulfiram neurotoxicity have also occurred, causing extrapyramidal and other symptoms.[13] Disulfiram (Antabuse) can produce neuropathy in daily doses of less than the usually recommended 500 mg. Nerve biopsies showed axonal degeneration and the neuropathy is difficult to distinguish from that associated with ethanol abuse. Disulfiram neuropathy occurs after a variable latent period (mean 5 to 6 months) and progresses steadily. Slow improvement may occur when the drug's use is stopped; often there is complete recovery eventually.[14]

Under normal metabolism, alcohol is broken down in the liver by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase to acetaldehyde, which is then converted by the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase to a harmless acetic acid derivative (acetyl coenzyme A). Disulfiram blocks this reaction at the intermediate stage by blocking acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. After alcohol intake under the influence of disulfiram, the concentration of acetaldehyde in the blood may be five to 10 times higher than that found during metabolism of the same amount of alcohol alone. As acetaldehyde is one of the major causes of the symptoms of a "hangover", this produces immediate and severe negative reaction to alcohol intake. About 5 to 10 minutes after alcohol intake, the patient may experience the effects of a severe hangover for a period of 30 minutes up to several hours. Symptoms include flushing of the skin, accelerated heart rate, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, throbbing headache, visual disturbance, mental confusion, postural syncope, and circulatory collapse.

Disulfiram disrupts metabolism of several other compounds, including paracetamol (acetaminophen),[15] theophylline[16] and caffeine.[17] However, in most cases, this disruption is mild and presents itself as a 20–40% increase in the half-life of the compound at typical dosages of disulfiram.

Occupational safety

Though the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in the US has not set a permissible exposure limit (PEL) for disulfiram in the workplace, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 2 mg/m3 and recommended that workers avoid concurrent exposure to ethylene dibromide.[18]

History

The synthesis of disulfiram, originally known as tetraethylthiuram disulfide, was first reported in 1881. By around 1900, it was introduced to the industrial process of Sulfur vulcanization of rubber and became widely used. In 1937 a rubber factory doctor in the US published a paper noting that workers exposed to disulfiram had negative reactions to alcohol and could be used as a drug for alcoholism; the effects were also noticed in workers at Swedish rubber boot factory.[19]

In the early 1940s it had been tested as a treatment for scabies, a parasitic skin infection, as well as intestinal worms.[19]

Around that time, during the German occupation of Denmark, Erik Jacobsen and Jens Hald at the Danish drug company Medicinalco picked up on that research and began exploring the use of disulfiram to treat intestinal parasites. The company had a group of enthusiastic self-experimenters that called itself the "Death Battalion", and in the course of testing the drug on themselves, accidentally discovered that drinking alcohol while the drug was still in their bodies made them mildly sick.[19][20]: 98–105

They made that discovery in 1945, and did nothing with it until two years later, when Jacobsen gave an impromptu talk and mentioned this self-experimental work and Disulframs nausea inducing effects when combined with alcohol, this talk which was discussed afterwards in newspapers at the time, lead them to further explore the use of the drug for aversive-reaction based therapy for the treatment of alcohol abuse.[19][20]: 98–105 That work included small clinical trials with Oluf Martensen-Larsen, a doctor who worked with alcoholics.[19] They published their work starting in 1948.[19][21]

The chemists at Medicinalco discovered a new form of disulfiram while trying to purify a batch that had been contaminated with copper. This form turned out to have better pharmacological properties, and the company patented it and used that form for the product that was introduced as Antabus (later anglicized to Antabuse).[19]

This work led to renewed study of the human metabolism of ethanol. It was already known that ethanol was mostly metabolized in the liver, with it being converted first to acetaldehyde and then acetaldehyde to acetic acid and carbon dioxide, but the enzymes involved were not known. By 1950 the work led to the knowledge that ethanol is oxidized to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase and acetaldehyde is oxidized to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), and that disulfiram works by inhibiting ALDH, leading to a buildup of acetaldehyde, which is what causes the negative effects in the body.[19]

The drug was first marketed in Denmark and as of 2008 Denmark was the country where it was most widely prescribed. It was approved by the FDA in 1951.[19][22]

Society and culture

Cost

In the United Kingdom 50 doses of 200 mg cost the NHS about 110 pounds as of 2020.[2] In the United States 60 doses of 250 mg costs as little as 42 USD as of 2020.[4]

.svg.png.webp) Disulfiram costs (US)

Disulfiram costs (US).svg.png.webp) Disulfiram prescriptions (US)

Disulfiram prescriptions (US)

Similarly substances

In medicine, the term "disulfiram effect" refers to side effect of a particular medication in causing an unpleasant hypersensitivity to alcohol, similar to the effect caused by disulfiram administration.

Examples:

- Antibiotics (nitroimidazoles), e.g. metronidazole

- First-generation sulfonylureas, e.g. tolbutamide and chlorpropamide

- Several cephalosporin drugs, including cefoperazone, cefamandole and cefotetan, that have a N-methylthio-tetrazole moiety

- Griseofulvin, an oral antifungal drug

- Procarbazine

- Temposil, or citrated calcium carbimide, has the same function as disulfiram, but is weaker and safer.

- Coprine, which metabolizes to 1-aminocyclopropanol, a chemical having the same metabolic effects as disulfiram. It occurs naturally in the otherwise edible common ink cap mushroom (Coprinopsis atramentaria), hence its colloquial name "tippler's bane". Similar reactions have been recorded with Clitocybe clavipes and Suillellus luridus, although the agent in those species is unknown.

Research

Disulfiram has been studied as a possible treatment for cancer[23] and latent HIV infection.[24]

Cancer

When disulfiram creates complexes with metals (dithiocarbamate complexes), it is a proteasome inhibitor and as of 2016 it had been studied in in vitro experiments, model animals, and small clinical trials as a possible treatment for liver metastasis, metastatic melanoma, glioblastoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and prostate cancer.[23][25] Various clinical trials of copper depletion agents have been carried out.

HIV

Disulfiram has also been identified by systematic high-throughput screening as a potential HIV latency reversing agent (LRA).[26][27] Reactivation of latent HIV infection in patients is part of an investigational strategy known as "shock and kill" which may be able to reduce or eliminate the HIV reservoir.[24] Recent phase II dose-escalation studies in patients with HIV who are controlled on antiretroviral therapy have observed an increase in cell-associated unspliced HIV RNA with increasing exposure to disulfiram and its metabolites.[26][28] Disulfiram is also being investigated in combination with vorinostat, another investigational latency reversing agent, to treat HIV.[29]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Disulfiram Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 BNF 79 : March 2020. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2020. p. 508, 509. ISBN 9780857113658.

- 1 2 "Antabuse – disulifram tablet". DailyMed. National Institutes of Health. May 23, 2016. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- 1 2 "Disulfiram Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips". GoodRx. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ↑ Smart, Reginald (2013). Research Advances in Alcohol and Drug Problems: Volume 7. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 400. ISBN 978-1-4613-3626-6. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ↑ Stokes M, Abdijadid S (January 2018). "Disulfiram". Stat Pearls. PMID 29083801. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- ↑ "Disulfiram Official FDA information, side effects and uses". Archived from the original on 2011-03-15. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ↑ Wright C, Moore RD (June 1990). "Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism". The American Journal of Medicine. 88 (6): 647–55. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(90)90534-K. PMID 2189310.

- ↑ "Disulfiram Side Effects". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ↑ Cornford EM, Bocash WD, Braun LD, Crane PD, Oldendorf WH, MacInnis AJ (June 1979). "Rapid distribution of tryptophol (3-indole ethanol) to the brain and other tissues". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 63 (6): 1241–8. doi:10.1172/JCI109419. PMC 372073. PMID 447842.

- ↑ "Antabuse (disulfiram)". netdoctor. November 18, 2013. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- ↑ Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2009). Chapter 3—Disulfiram. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). Archived from the original on 2021-04-20. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ↑ Boukriche Y, Weisser I, Aubert P, Masson C (September 2000). "MRI findings in a case of late onset disulfiram-induced neurotoxicity". Journal of Neurology. 247 (9): 714–5. doi:10.1007/s004150070119. PMID 11081815. S2CID 1982036.

- ↑ Watson CP, Ashby P, Bilbao JM (July 1980). "Disulfiram neuropathy". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 123 (2): 123–6. PMC 1704662. PMID 6266628.

- ↑ Poulsen HE, Ranek L, Jørgensen L (February 1991). "The influence of disulfiram on acetaminophen metabolism in man". Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems. 21 (2): 243–9. doi:10.3109/00498259109039466. PMID 2058179.

- ↑ Loi CM, Day JD, Jue SG, Bush ED, Costello P, Dewey LV, Vestal RE (May 1989). "Dose-dependent inhibition of theophylline metabolism by disulfiram in recovering alcoholics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 45 (5): 476–86. doi:10.1038/clpt.1989.61. PMID 2721103.

- ↑ Beach CA, Mays DC, Guiler RC, Jacober CH, Gerber N (March 1986). "Inhibition of elimination of caffeine by disulfiram in normal subjects and recovering alcoholics". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 39 (3): 265–70. doi:10.1038/clpt.1986.37. PMID 3948467.

- ↑ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0244". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kragh, Helge (2008). "From Disulfiram to Antabuse: The Invention of a Drug" (PDF). Bulletin for the History of Chemistry. 33 (2): 82–88. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2018-08-04.

- 1 2 Altman, Lawrence K. (1998). Who Goes First?: The Story of Self-Experimentation in Medicine. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520212817. Archived from the original on 2021-06-18. Retrieved 2018-08-04.

- ↑ Hald, Jens; Jacobsen, Erik; Larsen, Valdemar (July 1948). "The Sensitizing Effect of Tetraethylthiuramdisulphide (Antabuse) to Ethylalcohol". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 4 (3–4): 285–296. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1948.tb03350.x.

- ↑ "NDA 007883". FDA. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- 1 2 Jiao Y, Hannafon BN, Ding WQ (2016). "Disulfiram's Anticancer Activity: Evidence and Mechanisms". Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (11): 1378–1384. doi:10.2174/1871520615666160504095040. PMID 27141876.

- 1 2 Rasmussen TA, Lewin SR (July 2016). "Shocking HIV out of hiding: where are we with clinical trials of latency reversing agents?". Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 11 (4): 394–401. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000279. PMID 26974532. S2CID 25995091.

- ↑ Cvek B, Dvorak Z (August 2008). "The value of proteasome inhibition in cancer. Can the old drug, disulfiram, have a bright new future as a novel proteasome inhibitor?". Drug Discovery Today. 13 (15–16): 716–22. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2008.05.003. PMID 18579431.

- 1 2 Lee SA, Elliott JH, McMahon J, Hartogenesis W, Bumpus NN, Lifson JD, et al. (March 2019). "Population Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Disulfiram on Inducing Latent HIV-1 Transcription in a Phase IIb Trial". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 105 (3): 692–702. doi:10.1002/cpt.1220. PMC 6379104. PMID 30137649.

- ↑ Xing S, Bullen CK, Shroff NS, Shan L, Yang HC, Manucci JL, et al. (June 2011). "Disulfiram reactivates latent HIV-1 in a Bcl-2-transduced primary CD4+ T cell model without inducing global T cell activation". Journal of Virology. 85 (12): 6060–4. doi:10.1128/JVI.02033-10. PMC 3126325. PMID 21471244.

- ↑ Knights HD (2017). "A Critical Review of the Evidence Concerning the HIV Latency Reversing Effect of Disulfiram, the Possible Explanations for Its Inability to Reduce the Size of the Latent Reservoir In Vivo, and the Caveats Associated with Its Use in Practice". AIDS Research and Treatment. 2017: 8239428. doi:10.1155/2017/8239428. PMC 5390639. PMID 28465838.

- ↑ "Combination Latency Reversal With High Dose Disulfiram Plus Vorinostat in HIV-infected Individuals on ART - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-06-04. Retrieved 2019-03-23.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Toxicity, Mushroom - Disulfiramlike Toxins at eMedicine

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards Archived 2021-06-04 at the Wayback Machine