Phenylephrine

| |

-Phenylephrine_molecule_ball.png.webp) | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌfɛnəlˈɛfriːn, fiː-, -ɪn/ |

| Trade names | Many[1] |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Alpha-adrenergic agonist |

| Main uses | Decongestant, dilate the pupil, low blood pressure, hemorrhoids[2][3] |

| Side effects | Nausea, headache, anxiety[2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, in the nose, on the eye, intravenous, intramuscular |

| Onset of action | Very rapid (IV); within 20 min (by mouth)[2] |

| Duration of action | Up to 20 min (IV); 4 hrs (by mouth)[2] |

| Defined daily dose | 4 Mg[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 38% through GI tract |

| Protein binding | 95% |

| Metabolism | Liver (oxidative deamination) |

| Elimination half-life | 2.1–3.4 h |

| Chemical and physical data | |

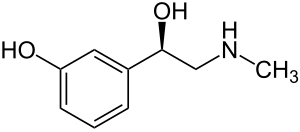

| Formula | C9H13NO2 |

| Molar mass | 167.205 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Phenylephrine is a medication primarily used as a decongestant, to dilate the pupil, to increase blood pressure, and to relieve hemorrhoids.[2][3] While marketed as a decongestant, taken by mouth at recommended doses it is of unclear benefit for hay fever.[2][5] It can be taken by mouth, given by injection into a vein or muscle, or applied to the skin.[2]

Common side effects when taken by mouth or injected include nausea, headache, and anxiety.[2] Use on hemorrhoids is generally well tolerated.[2] Severe side effects may include a slow heart rate, intestinal ischemia, chest pain, kidney failure, and tissue death at the site of injection.[2][3] It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe.[2] Phenylephrine is a selective α1-adrenergic receptor activator which results in the constriction of both arteries and veins.[2]

Phenylephrine was patented in 1927 and came into medical use in 1938.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In the United Kingdom the injectable formulation costs the NHS £4 per vial.[3] Unlike pseudoephedrine, abuse of phenylephrine is very uncommon.[7]

Medical uses

Decongestant

Phenylephrine is used as a decongestant by mouth and as a nasal spray. It is a common ingredient in over-the-counter decongestants in the United States. Its efficacy as an oral decongestant has been questioned, with several studies finding that it provided no more relief to sinus congestion than a placebo.[8][9][10]

A 2007 review concluded that the evidence for its effectiveness is insufficient,[11] though another review published shortly thereafter by researchers from GlaxoSmithKline found the standard 10-mg dose to be more effective than a placebo; however, the fact that GSK markets many products containing phenylephrine has raised concerns.[12]

Two studies published in 2009 examined the effects of phenylephrine on symptoms of allergic rhinitis by exposing people to pollen in a controlled, indoor environment. Neither study was able to distinguish between the effects of phenylephrine or a placebo. Pseudoephedrine and loratadine-montelukast therapy were found to be more effective than both phenylephrine and placebo.[8][9]

The Food and Drug Administration withdrew the indication "for the temporary relief of nasal congestion associated with sinusitis" in 2007.[2]

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are caused by swollen veins in the rectal area.[13] Phenylephrine can be used topically to prevent symptoms of hemorrhoids. Phenylephrine causes the constriction of vascular smooth muscle and is often used in the treatment of hemorrhoids presumably to narrow the swollen veins and relieve the attendant pain. However, veins—unlike arteries—contain less vascular smooth muscle in their walls so the mechanism by which pain relief is achieved is likely related to something other than vascular change alone. Products for treatment may also include substances that will form a protective barrier over the inflamed area, resulting in less pain when feces are passed.[14]

Phenylephrine hydrochloride at 0.25% is used as a vasoconstrictor in some suppository formulations.[15]

Low blood pressure

Phenylephrine is commonly used as a vasopressor to increase the blood pressure in people who are unstable with low blood pressure, especially resulting from septic shock. Such use is common in anesthesia or critical-care practices; it is especially useful in counteracting the low blood pressure effect of epidural and subarachnoid anesthetics, as well as the vasodilating effect of bacterial toxins and the inflammatory response in sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. The elimination half life of phenylephrine is about 2.5 to 3.0 hours.[16] The clinical effects of a single intravenous bolus dose of phenylephrine are short lived and may need further doses every 10–15 minutes. Commonly the drug is given as a carefully titrated intravenous infusion with a syringe pump or volumetric pump.

Phenylephrine has also been used to treat conditions of orthostatic intolerance such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Priapism

Phenylephrine is used to treat priapism. It is diluted with normal saline and injected directly into the corpora cavernosa. The mechanism of action is to cause constriction of the blood vessels entering into the penis, thus causing decreased blood flow and relieving the priapism. An injection is given every 3–5 minutes. If priapism is not resolved in 1 hour, another form of therapy is considered.[17]

Eyes

Phenylephrine is used as an eye drop to dilate the pupil to facilitate visualization of the retina. It is often used in combination with tropicamide as a synergist when tropicamide alone is not sufficient. Narrow-angle glaucoma is a contraindication to phenylephrine use. As a mydriatic, it is available in 2.5% and 10% minims. Phenylephrine eye drops are applied to the eye after a topical anesthetic is applied.[18]

Phenylephrine has been used as an intracameral injection into the anterior chamber of the eye to arrest intraocular bleeding occurring during cataract and glaucoma surgery.[19]

Dosage

For low blood pressure 100 micrograms by injection can be used.[20] It can also be given as a infusion starting at 100 to 200 micrograms per min and decreased down to 40 to 60 micrograms per minute.[20]

For priapism 100 to 500 micrograms may be injected into the base of the penis (after confirming that blood can be drawn back into the needle).[20] Doses can be given every 3 to 5 minutes to a maximum dose of 1,000 micrograms.[20]

The defined daily dose is 4 mg by injection.[4]

Side effects

Phenylephrine may cause side effects such as headache, reflex bradycardia, excitability, restlessness and cardiac arrhythmias. Phenylephrine is not suggested for use in patients with hypertension.[21]

Heart

The primary side effect of phenylephrine is high blood pressure. People with high blood pressure are typically advised to avoid products containing it. Because this medication is a sympathomimetic amine without beta-adrenergic activity, it does not increase contractility force and output of the cardiac muscle. It may increase blood pressure resulting in a slow heart rate through stimulation of vascular (likely carotid) baroreceptors. A common side effect during IV administration is reflex bradycardia.[22] The low concentration eye drops do not cause blood pressure changes and the changes with the higher dose drops do not last long.[23]

Necrosis

Because of its vasoconstrictive effect, phenylephrine can cause necrosis if it infiltrates the surrounding tissues. Because of this, it should be given through a central line when possible. If infiltration occurs damage may be prevented or lessened by infiltrating the tissue with the alpha blocker phentolamine by subcutaneous injection.[24]

Other

_(cropped).png.webp)

Prostatic hyperplasia can also be worsened by use, and chronic use can lead to rebound hyperemia.[25] People with a history of anxiety or panic disorders, or on anticonvulsant medication for epilepsy should not take this substance. The drug interaction might produce seizures. Some patients have been shown to have an upset stomach, severe abdominal cramping, and vomiting issues connected to taking this drug.[26]

Phenylephrine is pregnancy category C. Due to the lack of studies done in animals and in humans, it is not known whether there is harm to the fetus. Phenylephrine should only be given to pregnant women who have a clear need.[26]

Extended use may cause rhinitis medicamentosa, a condition of rebound nasal congestion.[27]

Interactions

The increase in blood pressure effect of phenylephrine may be increased by drugs such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and hydrocortisone. Patients taking these medications may need a lower dose of phenylephrine to achieve a similar increase in blood pressure.

Drugs that may decrease the effects of phenylephrine may include calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors and benzodiazepines. Patients taking these medications may need a higher dose of phenylephrine to achieve a comparable increase in blood pressure.[28]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Phenylephrine is a sympathomimetic drug, which means that it mimics the actions of epinephrine (commonly known as adrenaline) or norepinephrine. Phenylephrine selectively binds to alpha-1 receptors which cause blood vessels to constrict.[21]

Whereas pseudoephedrine causes both vasoconstriction and increase of mucociliary clearance through its nonspecific adrenergic activity, phenylephrine's selective α-adrenergic agonism causes vasoconstriction alone, creating a difference in their methods of action.

Pharmacokinetics

Oral phenylephrine is extensively metabolized by monoamine oxidase,[1] an enzyme that is present on the mitochondrial membrane of cells throughout the body.[29] Compared to intravenous pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine has a reduced and variable bioavailability; only up to 38%.[1][30]

Society and culture

Cost

In the United Kingdom the injectable formulation costs the NHS £4 per vial.[3]

.svg.png.webp) Phenylephrine costs (US)

Phenylephrine costs (US).svg.png.webp) Phenylephrine prescriptions (US)

Phenylephrine prescriptions (US)

Availability

Pseudoephedrine was previously much more commonly available in the United States, however, provisions of the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005 placed restrictions on the sale of pseudoephedrine products to prevent the clandestine manufacture of methamphetamine. Since 2004, phenylephrine has been increasingly marketed as a substitute for pseudoephedrine; some manufacturers have changed the active ingredients of products to avoid the restrictions on sales.[31] Phenylephrine has been off patent for some time, and many generic brands are available.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Phenylephrine (DB00388)". DrugBank. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Phenylephrine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76, 1140 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 188–189. ISBN 9780857113382.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ Luscombe, Richard (12 September 2023). "Decongestant ingredient in popular products does not work, FDA concludes". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 September 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 541. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2019-01-10.

- ↑ "Max Strength Decongestant Tablets" (PDF). www.mhra.gov.uk. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- 1 2 Horak F, Zieglmayer P, Zieglmayer R, Lemell P, Yao R, Staudinger H, Danzig M (February 2009). "A placebo-controlled study of the nasal decongestant effect of phenylephrine and pseudoephedrine in the Vienna Challenge Chamber". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 102 (2): 116–20. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60240-2. PMID 19230461.

- 1 2 Day JH, Briscoe MP, Ratz JD, Danzig M, Yao R (April 2009). "Efficacy of loratadine-montelukast on nasal congestion in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis in an environmental exposure unit". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 102 (4): 328–38. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60339-0. PMID 19441605.

- ↑ Hendeles L, Hatton RC (July 2006). "Oral phenylephrine: an ineffective replacement for pseudoephedrine?". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 118 (1): 279–80. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.03.002. PMID 16815167.

- ↑ Hatton RC, Winterstein AG, McKelvey RP, Shuster J, Hendeles L (March 2007). "Efficacy and safety of oral phenylephrine: systematic review and meta-analysis". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 41 (3): 381–90. doi:10.1345/aph.1H679. PMID 17264159. Archived from the original (abstract) on 2007-02-27.(published online Jan 2007)

- ↑ Kollar C, Schneider H, Waksman J, Krusinska E (June 2007). "Meta-analysis of the efficacy of a single dose of phenylephrine 10 mg compared with placebo in adults with acute nasal congestion due to the common cold". Clinical Therapeutics. 29 (6): 1057–70. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.05.021. PMID 17692721.

- ↑ "Hemorrhoids". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2014-11-03.

- ↑ "Phenylephrine rectal". WebMD. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Preparation H – cocoa butter and phenylephrine hydrochloride suppository". DailyMed. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Kanfer I, Dowse R, Vuma V (1993). "Pharmacokinetics of oral decongestants". Pharmacotherapy. 13 (6 Pt 2): 116S–128S, discussion 143S–146S. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1993.tb02780.x (inactive 2020-01-22). PMID 7507589.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2020 (link) - ↑ "Priapism". American Urological Association. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Phenylephrine Hydrochloride Ophthalmic Solution, USP 2.5% — Sterile" (PDF). Akorn. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Bizrah M, Corbett MC (March 2019). "Intracameral Phenylephrine to Arrest Intraoperative Intraocular Bleeding: A New Technique". Ophthalmology and Therapy. 8 (1): 137–141. doi:10.1007/s40123-019-0165-y. PMC 6393249. PMID 30771215.

- 1 2 3 4 "Phenylephrine - WikEM". wikem.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- 1 2 "Phenylephrine hydrochloride injection". DailyMed. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Phenylephrine (Rx)". Medscape. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Stavert B, McGuinness MB, Harper CA, Guymer RH, Finger RP (June 2015). "Cardiovascular Adverse Effects of Phenylephrine Eyedrops: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Ophthalmology. 133 (6): 647–52. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0325. PMID 25789577.

- ↑ Cooper BE (2008). "Review and update on inotropes and vasopressors". AACN Advanced Critical Care. 19 (1): 5–13, quiz 14–5. doi:10.1097/01.AACN.0000310743.32298.1d. PMID 18418098.

- ↑ Shen, Howard (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-59541-101-3.

- 1 2 "Phenylephrine Hydrochloride injection, for intravenous use" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-03.

- ↑ "Neo-Synephrine Nasal Spray Drug Information, Professional". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "Vazculep Package Insert" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2018-08-31.

- ↑ Shih JC, Chen K (August 2004). "Regulation of MAO-A and MAO-B gene expression". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (15): 1995–2005. doi:10.2174/0929867043364757. PMID 15279563.

- ↑ "Recommendation on phenylephrine". New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. November 2004. Archived from the original on 2006-05-26. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- ↑ Hilenmeyer K (30 January 2007). "All stuffed up". Southwest Florida Herald-Tribune. Archived from the original on 1 March 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Phenylephrine". U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal. Archived from the original on 2010-09-16. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- McAuley, David. "Neosynephrine Intravenous DIlution Guidelines". Global Rx Ph. Archived from the original on 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2012-07-09.