Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis

| Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, keratoconjunctivitis epidemica, pink eye[1] | |

| |

| Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology, infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Painful red eye, discomfort/irritation, sensitivity to light, watering, blurred vision, discharge[2] |

| Complications | Corneal scarring[3] |

| Usual onset | Sudden in an adult[4] |

| Duration | 7-10 days, can be longer[4] |

| Causes | Adenoviruses, commonly types 8 and 37[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Visualisation, viral culture (with immunofluorescence staining), PCR[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Herpes simplex type I, acanthamoeba, fungal infection[5] |

| Prevention | Hand washing,[4] adenovirus vaccine (military personnel)[4] |

| Treatment | Usually none, cold compress, artificial tears[3] |

| Frequency | Epidemics, common, adults>children[3] |

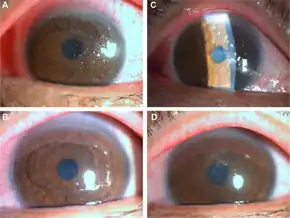

Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis, also known as epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, is a type of adenovirus disease presenting as an eye infection.[6] It typically begins in one eye with sudden onset of redness, watery discharge, and feeling that something is in the eye.[2] There may also be eye pain, intolerance to light, blurry vision, and swollen glands by the ear near the affected eye.[3][7] It is associated with a sore throat and stuffy and runny nose, mainly in adults.[4] In young children high fever, sore throat, ear infection, vomiting, and diarrhea may also occur.[4]

It is commonly caused by adenovirus types 8 and 37.[4] It is contagious and spread by contaminated eye examination instruments and eye solutions, touching eyes by infected people, inadequately chlorinated swimming pools, or other contaminated objects.[4] The time between contact and onset of symptoms is around 5–10 days.[4] Diagnosis is usually based on symptoms and examination.[1]

Usually, the condition is better after 7 to 10-days, with no specific treatment required.[4] Cold compresses and artificial tears may help.[3] Corneal scarring occurs in up to half of cases and the blurred vision may continue for a long time in some people.[3] The virus may remain in the eye for 2 to 3-years after recovering.[4]

Globally it is a common cause of a red eye and tends to occur in large numbers of people at the same time.[3] Adults tend to be affected more frequently than children.[4]

Signs and symptoms

It typically begins in one eye with sudden onset of redness, watery discharge, and feeling that something is in the eye.[2] The eye may be very painful.[7] It then develops with intolerance to light, blurred vision and swollen glands by the ear nearest the affected eye.[3] It may spread to the other eye.[2] The condition is part of adenovirus disease, where it is often associated with a sore throat and stuffy and runny nose, mainly in adults.[4] A type of adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis in very small children can present with a high fever, sore throat, ear infection, vomiting and diarrhea.[4]

Cause

It is commonly caused by types 8 and 37 adenoviruses, spread by contaminated eye examination instruments and eye solutions, touching eyes by infected people, from inadequately chlorinated swimming pools, or other contaminated objects.[4] Onset of symptoms is generally around 5–10 days after exposure.[4] From the onset of symptoms, people remain contagious for about 2 weeks.[1]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on symptoms and examination.[1] Occasionally, it may be confirmed by cell culture (with immunofluorescence staining) or PCR.[5]

It may appear similar to herpes simplex type I, acanthamoeba, and fungal infection.[5]

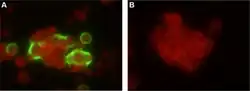

Adenovirus in the HEp-2 cells derived from swab samples (by indirect immunofluorescence assay).

Adenovirus in the HEp-2 cells derived from swab samples (by indirect immunofluorescence assay).

Prevention

Adequate infection control measures should be followed as prevention and to reduce epidemic AKC outbreaks.[8]

Treatment

There is currently no effective treatment of the acute phase of AKC.[1] Measures like application of a cool cloth or artificial tears may help with the symptoms.[1]

Topical cidofovir may reduce the incidence of corneal opacities, but local toxicity rules out its use. NMSO3, a sulfated sialyl lipid, has demonstrated a greater antiviral potency against adenovirus in vitro than cidofovir exhibiting minimal cytotoxicity.[9] Topical cyclosporin A (CsA) appears to be effective in for persistent corneal opacities. Topical interferon might be effective to prevent infection; though is not commercially available due to unsettled patent issues.

Topical steroids should be avoided because they prolong viral replication, frequently lead to long-lasting dry eye symptoms, and corneal opacities almost always recur after discontinuation of topical steroids.

Epidemiology

Globally it is a common cause of a red eye and tends to occur in large numbers of people at the same time.[3] Adults tend to be affected more frequently than children.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis - EyeWiki". eyewiki.aao.org. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Burrow, Michael K.; Patel, Bhupendra C. (2022). "Keratoconjunctivitis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31194419.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bawazeer, Ahmed (4 June 2019). "Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis (EKC)". Medscape. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Shieh, Wun-Ju (10 September 2021). "Human adenovirus infections in pediatric population - An update on clinico-pathologic correlation". Biomedical Journal: S2319–4170(21)00109–8. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2021.08.009. ISSN 2320-2890. PMID 34506970. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 Pihos, Andria M. (April 2013). "Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis: A review of current concepts in management". Journal of Optometry. 6 (2): 69–74. doi:10.1016/j.optom.2012.08.003. ISSN 1888-4296. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ↑ Ison, Michael G. (2019). "341. Adenovirus diseases". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine (26th ed.). Elsevier. p. 2163. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1. Archived from the original on 2022-04-28. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- 1 2 Flint, S. Jane; Nemerow, Glen R. (2017). "8. Pathogenesis". Human Adenoviruses: From Villains To Vectors. Singapore: World Scientific. p. 153-183. ISBN 978-981-310-979-7. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- ↑ Reinhard, Thomas; Larkin, Frank (28 January 2006). Cornea and External Eye Disease. google.com.au. ISBN 9783540312260. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ Kaneko H; et al. (2001). "Antiviral activity of NMSO3 against adenovirus in vitro". Antiviral Res. 52 (3): 281–8. doi:10.1016/s0166-3542(01)00167-x. PMID 11675145.