Cidofovir

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vistide |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antiviral[1] |

| Main uses | CMV retinitis, herpes simplex virus, monkeypox[1] |

| Side effects | Kidney problems, nausea, fever, low white blood cells, headache, rash, hair loss, diarrhea, heart burn[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | IV |

| Typical dose | 5 mg/kg[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | Complete |

| Protein binding | <6% |

| Elimination half-life | 2.6 hours (active metabolites: 15-65 hours) |

| Excretion | Kidney The above pharmacokinetics are with probenecid.[3] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

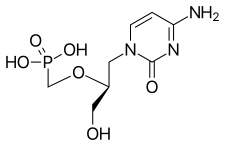

| Formula | C8H14N3O6P |

| Molar mass | 279.189 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Specific rotation | -97.3 |

| Melting point | 260 °C (500 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Cidofovir, sold under the brand name Vistide, is an antiviral used to treat cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis in people with HIV/AIDS.[1] Is also used for herpes simplex virus that is resistant to acyclovir, monkeypox, and certain complications of smallpox vaccination.[1] It is generally given by injection into a vein.[1]

Common side effects include kidney problems, nausea, fever, low white blood cells, headache, rash, hair loss, diarrhea, and heart burn.[1] Other side effects may include pancreatitis, male infertility, and hearing loss.[2] It is given with intravenous fluids and probenecid to decrease the risk of kidney problems.[2] There are concerns that use in pregnancy may harm the baby.[1] It works by blocking the DNA polymerase of the virus.[2]

Cidofovir was approved for medical use in the United States 1996.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[2] In the United States 375 mg costs about 215 USD as of 2021.[5]

Medical use

DNA virus

Its only indication that has received regulatory approval worldwide is cytomegalovirus retinitis.[6][7] Cidofovir has also shown efficacy in the treatment of aciclovir-resistant HSV infections.[8] Cidofovir has also been investigated as a treatment for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with successful case reports of its use.[9] Despite this, the drug failed to demonstrate any efficacy in controlled studies.[10] Cidofovir might have anti-smallpox efficacy and might be used on a limited basis in the event of a bioterror incident involving smallpox cases.[11] Brincidofovir, a cidofovir derivative with much higher activity against smallpox that can be taken orally has been developed.[12] It has inhibitory effects on varicella-zoster virus replication in vitro although no clinical trials have been done to date, likely due to the abundance of safer alternatives such as aciclovir.[13] Cidofovir shows anti-BK virus activity in a subgroup of transplant recipients.[14] Cidofovir is being investigated as a complementary intralesional therapy against papillomatosis caused by HPV.[15][16]

It first received FDA approval on 26 June 1996,[17] TGA approval on 30 April 1998[7] and EMA approval on 23 April 1997.[18]

Other

It has been suggested as an antitumour agent, due to its suppression of FGF2.[20][21]

Administration

For CMV retinitis it is given at a dose of 5 mg/kg once per week for two weeks and than 5 mg every two weeks.[2]

Cidofovir is only available as an intravenous formulation. Cidofovir is to be administered with probenecid which decreases side effects to the kidney.[22] Probenecid mitigates nephrotoxicity by inhibiting organic anion transport of the proximal tubule epithelial cells of the kidney.[23] In addition, hydration such as 1 liter of normal saline is recommended in conjunction with each dose.[22]

Side effects

The major dose-limiting side effect of cidofovir is nephrotoxicity (that is, kidney damage).[24] Other common side effects (occurring in >1% of people treated with the drug) include:[6][24]

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Neutropenia

- Hair loss

- Weakness

- Headache

- Chills

- Decreased intraocular pressure

- Uveitis

- Iritis

Whereas uncommon side effects include: anaemia and elevated liver enzymes and rare side effects include: tachycardia and Fanconi syndrome.[24] Probenecid (a uricosuric drug) and intravenous saline should always be administered with each cidofovir infusion to prevent this nephrotoxicity.[25]

Contraindications

Hypersensitivity to cidofovir or probenecid (as probenecid needs to be given concurrently to avoid nephrotoxicity).[6]

Interactions

It is known to interact with nephrotoxic agents (e.g. amphotericin B, foscarnet, IV aminoglycosides, IV pentamide, vancomycin, tacrolimus, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, etc.) to increase their nephrotoxic potential.[6][7] As it must be given concurrently with probenecid it is advised that drugs that are known to interact with probenecid (e.g. drugs that probenecid interferes with the renal tubular secretion of, such as paracetamol, aciclovir, aminosalicylic acid, etc.) are also withheld.[7]

Mechanism of action

Its active metabolite, cidofovir diphosphate, inhibits viral replication by selectively inhibiting viral DNA polymerases.[7] It also inhibits human polymerases but this action is 8-600 times weaker than its actions on viral DNA polymerases.[7] It also incorporates itself into viral DNA hence inhibiting viral DNA synthesis during reproduction.[7]

It possesses in vitro activity against the following viruses:[26]

- Human herpesviruses

- Adenoviruses

- Human poxviruses (including the smallpox virus)

- Human papillomavirus

History

Cidofovir was discovered at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry, Prague, by Antonín Holý, and developed by Gilead Sciences[27] and is marketed with the brand name "Vistide" by Gilead in the USA, and by Pfizer elsewhere.

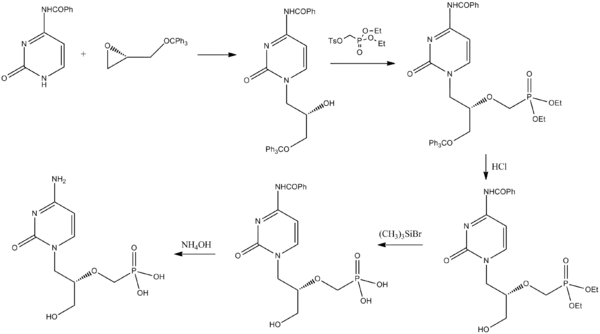

Synthesis

Cidofovir can be synthesized from a pyrimidone derivative and a protected derivative of glycidol.[28]

See also

- Brincidofovir, a prodrug of cidofovir that can be taken by mouth

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Cidofovir Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 676. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- ↑ Cundy, Kenneth C. "Clinical Pharmacokinetics of the Antiviral Nucleotide Analogues Cidofovir and Adefovir." Clinical Pharmacokinetics 36.2 (1999): 127-43.

- ↑ Long, Sarah S.; Pickering, Larry K.; Prober, Charles G. (2012). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1502. ISBN 978-1437727029. Archived from the original on 2019-12-29. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ↑ "Cidofovir Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Vistide (cidofovir) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Product Information VISTIDE®". TGA eBusiness Services. Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd. 3 September 2013. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ↑ Chilukuri, S; Rosen, T (Apr 2003). "Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus". Dermatologic Clinics. 21 (2): 311–20. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1. PMID 12757254.

- ↑ Segarra-Newnham M, Vodolo KM (June 2001). "Use of cidofovir in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy". Ann Pharmacother. 35 (6): 741–4. doi:10.1345/aph.10338. PMID 11408993. S2CID 32026770.

- ↑ De Gascun, C. F.; Carr, M. J. (2013). "Human polyomavirus reactivation: Disease pathogenesis and treatment approaches". Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2013: 1–27. doi:10.1155/2013/373579. PMC 3659475. PMID 23737811.

- ↑ De Clercq E (July 2002). "Cidofovir in the treatment of poxvirus infections". Antiviral Res. 55 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00008-6. PMID 12076747.

- ↑ Bradbury, J (March 2002). "Orally available cidofovir derivative active against smallpox". Lancet. 359 (9311): 1041. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08115-1. PMID 11937193. S2CID 22903225.

- ↑ Magee, WC; Hostetler, KY; Evans, DH (August 2005). "Mechanism of Inhibition of Vaccinia Virus DNA Polymerase by Cidofovir Diphosphate". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 49 (8): 3153–3162. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.8.3153-3162.2005. PMC 1196213. PMID 16048917.

- ↑ Araya CE, Lew JF, Fennell RS, Neiberger RE, Dharnidharka VR (February 2006). "Intermediate-dose cidofovir without probenecid in the treatment of BK virus allograft nephropathy". Pediatr Transplant. 10 (1): 32–7. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00391.x. PMID 16499584. S2CID 24131709.

- ↑ Broekema FI, Dikkers FG (August 2008). "Side-effects of cidofovir in the treatment of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis". Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 265 (8): 871–9. doi:10.1007/s00405-008-0658-0. PMC 2441494. PMID 18458927.

- ↑ Soma MA, Albert DM (February 2008). "Cidofovir: to use or not to use?". Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 16 (1): 86–90. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e3282f43408. PMID 18197029. S2CID 22895067.

- ↑ "Cidofovir Monograph for Professionals - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ↑ "Vistide : EPAR -Product Information" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Gilead Sciences International Ltd. 7 November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ↑ Fernández-Morano, T; del Boz J; González-Carrascosa M (2011). "Topical cidofovir for viral warts in children". J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 25 (12): 1487–9. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03961.x. PMID 21261749. S2CID 32295082.

- ↑ Liekens S, Gijsbers S, Vanstreels E, Daelemans D, De Clercq E, Hatse S (March 2007). "The nucleotide analog cidofovir suppresses basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) expression and signaling and induces apoptosis in FGF2-overexpressing endothelial cells". Mol. Pharmacol. 71 (3): 695–703. doi:10.1124/mol.106.026559. PMID 17158200. S2CID 42400272.

- ↑ Liekens S (2008). "Regulation of cancer progression by inhibition of angiogenesis and induction of apoptosis". Verh. K. Acad. Geneeskd. Belg. 70 (3): 175–91. PMID 18669159.

- 1 2 "Details" (PDF). www.gilead.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ↑ Lacy, S. "Effect of Oral Probenecid Coadministration on the Chronic Toxicity and Pharmacokinetics of Intravenous Cidofovir in Cynomolgus Monkeys.

- 1 2 3 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ "Vistide (cidofovir)" (PDF) (package insert). Gilead Sciences. September 2010. DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION: Dosage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ↑ Safrin, S; Cherrington, J; Jaffe, HS (September 1997). "Clinical uses of cidofovir". Reviews in Medical Virology. 7 (3): 145–156. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199709)7:3<145::AID-RMV196>3.0.CO;2-0. PMID 10398479.

- ↑ "Press Releases: Gilead". Archived from the original on 2013-02-08. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ↑ Brodfuehrer, P; Howell, Henry G.; Sapino, Chester; Vemishetti, Purushotham (1994). "A practical synthesis of (S)-HPMPC". Tetrahedron Letters. 35 (20): 3243. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)76875-4.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|