Atypical trigeminal neuralgia

| Atypical trigeminal neuralgia | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Type 2 trigeminal neuralgia | |

| |

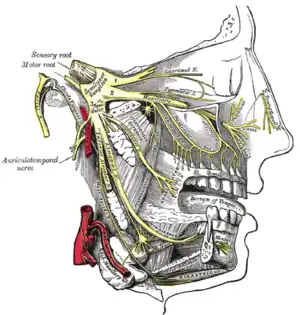

| Detailed view of trigeminal nerve, shown in yellow. | |

Atypical trigeminal neuralgia (ATN), or type 2 trigeminal neuralgia, is a form of trigeminal neuralgia, a disorder of the fifth cranial nerve. This form of nerve pain is difficult to diagnose, as it is rare and the symptoms overlap with several other disorders.[1] The symptoms can occur in addition to having migraine headache, or can be mistaken for migraine alone, or dental problems such as temporomandibular joint disorder or musculoskeletal issues. ATN can have a wide range of symptoms and the pain can fluctuate in intensity from mild aching to a crushing or burning sensation, and also to the extreme pain experienced with the more common trigeminal neuralgia.

Signs and symptoms

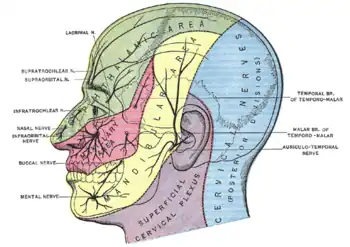

ATN pain can be described as heavy, aching, stabbing, and burning. Some patients have a constant migraine-like headache. Others may experience intense pain in one or in all three trigeminal nerve branches, affecting teeth, ears, sinuses, cheeks, forehead, upper and lower jaws, behind the eyes, and scalp. In addition, those with ATN may also experience the shocks or stabs found in type 1 TN.

Many TN and ATN patients have pain that is "triggered" by light touch on shifting trigger zones. ATN pain tends to worsen with talking, smiling, chewing, or in response to sensations such as a cool breeze. The pain from ATN is often continuous, and periods of remission are rare. Both TN and ATN can be bilateral, though the character of pain is usually different on the two sides at any one time.[2]

Causes

ATN is usually attributed to inflammation or demyelination, with increased sensitivity of the trigeminal nerve. These effects are believed to be caused by infection, demyelinating diseases, or compression of the trigeminal nerve (by an impinging vein or artery, a tumor, dental trauma, accidents, or arteriovenous malformation) and are often confused with dental problems. Though TN and ATN most often present in the fifth decade, cases have been documented as early as infancy.

Risk factors

Both forms of facial neuralgia are relatively rare, with an incidence recently estimated between 12 and 24 new cases per hundred thousand population per year.[3][4]

ATN often goes undiagnosed or misdiagnosed for extended periods, leading to a great deal of unexplained pain and anxiety. A National Patient Survey conducted by the US Trigeminal Neuralgia Association in the late 1990s indicated that the average facial neuralgia patient may see six different physicians before receiving a first definitive diagnosis. The first practitioner to see facial neuralgia patients is often a dentist who may lack deep training in facial neurology. Thus ATN may be misdiagnosed as Temporomandibular Joint Disorder.[5]

This disorder is regarded by many medical professionals to comprise the most severe form of chronic pain known in medical practice. In some patients, pain may be unresponsive even to opioid drugs at any dose level that leaves the patient conscious. The disorder has thus acquired the unfortunate and possibly inflammatory nickname, "the suicide disease".[6]

Symptoms of ATN may overlap with a pain disorder occurring in teeth called atypical odontalgia (literal meaning "unusual tooth pain"), with aching, burning, or stabs of pain localized to one or more teeth and adjacent jaw. The pain may seem to shift from one tooth to the next, after root canals or extractions. In desperate efforts to alleviate pain, some patients undergo multiple (but unneeded) root canals or extractions, even in the absence of suggestive X-ray evidence of dental abscess.

ATN symptoms may also be similar to those of post-herpetic neuralgia, which causes nerve inflammation when the latent herpes zoster virus of a previous case of chicken pox re-emerges in shingles. Fortunately, post-herpetic neuralgia is generally treated with medications that are also the first medications tried for ATN, which reduces the negative impact of misdiagnosis.

The subject of atypical trigeminal neuralgia is considered problematic even among experts. The term atypical TN is broad and due to the complexity of the condition, there are considerable issues with defining the condition further. Some medical practitioners no longer make a distinction between facial neuralgia (a nominal condition of inflammation) versus facial neuropathy (direct physical damage to a nerve).

Due to the variability and imprecision of their pain symptoms, ATN or atypical odontalgia patients may be misdiagnosed with atypical facial pain (AFP) or "hypochondriasis", both of which are considered problematic by many practitioners.[7] The term "atypical facial pain" is sometimes assigned to pain which crosses the mid-line of the face or otherwise does not conform to expected boundaries of nerve distributions or characteristics of validated medical entities. As such, AFP is seen to comprise a diagnosis by reduction.

As noted in material published by the [US] National Pain Foundation: "atypical facial pain is a confusing term and should never be used to describe patients with trigeminal neuralgia or trigeminal neuropathic pain. Strictly speaking, AFP is classified as a "somatiform pain disorder"; this is a psychological diagnosis that should be confirmed by a skilled pain psychologist. Patients with the diagnosis of AFP have no identifiable underlying physical cause for the pain. The pain is usually constant, described as aching or burning, and often affects both sides of the face (this is almost never the case in patients with trigeminal neuralgia). The pain frequently involves areas of the head, face, and neck that are outside the sensory territories that are supplied by the trigeminal nerve. It is important to correctly identify patients with AFP since the treatment for this is strictly medical. Surgical procedures are not indicated for atypical facial pain."[8]

The term "hypochondriasis" is closely related to "somatoform pain disorder" and "conversion disorder" in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) of the American Psychiatric Association. As of July 2011, this axis of the DSM-IV is undergoing major revision for the DSM-V, with introduction of a new designation "Complex Somatic Symptom Disorder". However, it remains to be demonstrated that any of these "disorders" can reliably be diagnosed as a medical entity with a discrete and reliable course of therapy.[9][10][11][12]

It is possible that there are triggers or aggravating factors that patients need to learn to recognize to help manage their health. Bright lights, sounds, stress, and poor diet are examples of additional stimuli that can contribute to the condition. The pain can cause nausea, so beyond the obvious need to treat the pain, it is important to be sure to try to get adequate rest and nutrition.

Depression is frequently co-morbid with neuralgia and neuropathic pain of all sorts, as a result of the negative effects that pain has on one's life. Depression and chronic pain may interact, with chronic pain often predisposing patients to depression, and depression operating to sap energy, disrupt sleep and heighten sensitivity and the sense of suffering. Dealing with depression should thus be considered equally important as finding direct relief from the pain.[13]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis for ATN is more difficult and complex than typical TN. However, the diagnosis for ATN can be supported by a positive response to a low dose of tricyclic antidepressant medications (such as amitriptyline or nortriptyline), similar to neuropathic pain diagnoses.[14]

Treatment

Medication

Treatment of people believed to have ATN or TN is usually begun with medication. The long-time first drug of choice for facial neuralgia has been carbamazepine, an anti-seizure agent. Due to the significant side-effects and hazards of this drug, others have recently come into common use as alternatives. These include oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, and gabapentin. A positive patient response to one of these medications might be considered as supporting evidence for the diagnosis, which is otherwise made from medical history and pain presentation. There are no present medical tests to conclusively confirm TN or ATN.

If the anti-seizure drugs are found ineffective, one of the tricyclic antidepressant medications, such as amitriptyline or nortriptyline, may be used. The tricyclic antidepressants are known to have dual action against both depression and neuropathic pain. Other drugs which may also be tried, either individually or in combination with an anti-seizure agent, include baclofen, pregabalin, and opioid drugs such as oxycodone or an oxycodone/paracetamol combination.

For some people with ATN opioids may represent the only viable medical option which preserves quality of life and personal functioning. Although there is considerable controversy in public policy and practice in this branch of medicine, practice guidelines have long been available and published.[17][18][19]

Surgery

If drug treatment is found to be ineffective or causes disabling side effects, one of several neurosurgical procedures may be considered. The available procedures are believed to be less effective with type II (atypical) trigeminal neuralgia than with type I (typical or "classic") TN. Among present procedures, the most effective and long lasting has been found to be microvascular decompression (MVD), which seeks to relieve direct compression of the trigeminal nerve by separating and padding blood vessels in the vicinity of the emergence of this nerve from the brain stem, below the cranium.[20]

Choice of a surgical procedure is made by the doctor and patient in consultation, based on the patient's pain presentation and health and the doctor's medical experience. Some neurosurgeons resist the application of MVD or other surgeries to atypical trigeminal neuralgia, in light of a widespread perception that ATN pain is less responsive to these procedures. However, recent papers suggest that in cases where pain initially presents as type I TN, surgery may be effective even after the pain has evolved into type II.[21]

References

- ↑ Quail G (August 2005). "Atypical facial pain--a diagnostic challenge". Aust Fam Physician. 34 (8): 641–5. PMID 16113700.

- ↑ R.A. Lawhern, Ph.D., "Classification and Treatment of Chronic Face Pain Archived 2019-02-20 at the Wayback Machine"

- ↑ Koopman JS, Dieleman JP, Huygen FJ, de Mos M, Martin CG, Sturkenboom MC (December 2009). "Incidence of facial pain in the general population". Pain. 147 (1–3): 122–7. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.023. PMID 19783099. S2CID 35327709.

- ↑ Hall GC, Carroll D, Parry D, McQuay HJ (May 2006). "Epidemiology and treatment of neuropathic pain: the UK primary care perspective". Pain. 122 (1–2): 156–62. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.030. PMID 16545908. S2CID 6844949.

- ↑ Drangsholt M, Truelove EL (July 2001). "Trigeminal Neuralgia Mistaken as Temporomandibular Disorder". J Evid Base Dent Pract. 1 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1067/med.2001.116846. Archived from the original on 2019-12-08. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ TN "Trigeminal Neuralgia Description / Definition", [US] Facial Pain Association, "TN (Trigeminal Neuralgia) Description / Definition | TNA the Facial Pain Association". Archived from the original on 2011-10-04. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- ↑ Graff-Radford SB, Solberg WK (May 1993). "Is atypical odontalgia a psychological problem?". Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 75 (5): 579–82. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(93)90228-v. PMID 8155097.

- ↑ National Pain Foundation, "Trigeminal Neuralgia — Definitions" Archived 2011-10-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Rief W, Isaac M (March 2007). "Are somatoform disorders 'mental disorders'? A contribution to the current debate". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 20 (2): 143–6. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280346999. PMID 17278912. S2CID 23584862.

- ↑ Voigt K, Nagel A, Meyer B, Langs G, Braukhaus C, Löwe B (May 2010). "Towards positive diagnostic criteria: a systematic review of somatoform disorder diagnoses and suggestions for future classification". J Psychosom Res. 68 (5): 403–14. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.015. PMID 20403499.

- ↑ Kroenke K, Sharpe M, Sykes R (2007). "Revising the classification of somatoform disorders: key questions and preliminary recommendations". Psychosomatics. 48 (4): 277–85. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.631.4736. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.48.4.277. PMID 17600162. Archived from the original on 2012-07-30.

- ↑ Dimsdale J, Sharma N, Sharpe M (2011). "What do physicians think of somatoform disorders?". Psychosomatics. 52 (2): 154–9. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2010.12.011. PMID 21397108.

- ↑ Daniel K. Hall-Flavin, MD, "Depression (Major Depression) Archived 2013-11-09 at the Wayback Machine", Mayo Clinic Expert Answers

- ↑ "Trigeminal Neuralgia Fact Sheet". ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

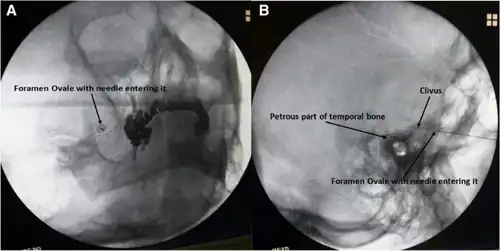

- ↑ Akbas, Mert; Salem, Haitham Hamdy; Emara, Tamer Hussien; Dinc, Bora; Karsli, Bilge (1 July 2019). "Radiofrequency thermocoagulation in cases of atypical trigeminal neuralgia: a retrospective study". The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery. 55 (1): 46. doi:10.1186/s41983-019-0092-9. ISSN 1687-8329. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ↑ Lopez, Benjamin C.; Hamlyn, Peter J.; Zakrzewska, Joanna M. (1 April 2004). "Systematic Review of Ablative Neurosurgical Techniques for the Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia" (PDF). Neurosurgery. 54 (4): 973–983. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000114867.98896.F0.

- ↑ O'Connor AB, Dworkin RH (October 2009). "Treatment of neuropathic pain: an overview of recent guidelines". Am. J. Med. 122 (10 Suppl): S22–32. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.04.007. PMID 19801049.

- ↑ Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Audette J, et al. (March 2010). "Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update". Mayo Clin. Proc. 85 (3 Suppl): S3–14. doi:10.4065/mcp.2009.0649. PMC 2844007. PMID 20194146. Archived from the original on 2013-01-28.

- ↑ Vadalouca A, Siafaka I, Argyra E, Vrachnou E, Moka E (November 2006). "Therapeutic management of chronic neuropathic pain: an examination of pharmacologic treatment". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1088 (1): 164–86. Bibcode:2006NYASA1088..164V. doi:10.1196/annals.1366.016. PMID 17192564. S2CID 21295855.

- ↑ Sindou M, Leston J, Decullier E, Chapuis F (December 2007). "Microvascular decompression for primary trigeminal neuralgia: long-term effectiveness and prognostic factors in a series of 362 consecutive patients with clear-cut neurovascular conflicts who underwent pure decompression". J. Neurosurg. 107 (6): 1144–53. doi:10.3171/JNS-07/12/1144. PMID 18077952.

- ↑ Tiril Sandell, M.D, Per Kristian Eide, M.D., Ph.D. "Effect of Microvascular Decompression in Trigeminal Neuralgia Patients with or without Constant Pain". Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Note: registration with the Facial Pain Association is required for access to this article.

External links

- Trigeminal Neuralgia Fact Sheet Archived 2016-11-19 at the Wayback Machine National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |