Oxcarbazepine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ɒks.kɑːrˈbæz.ɪˌpiːn/ |

| Trade names | Trileptal, Oxtellar XR, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Epilepsy, bipolar disorder[1] |

| Side effects | Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, double vision, trouble with walking[2] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

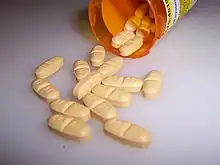

| Routes of use | By mouth (tablets or liquid)[3] |

| Defined daily dose | 1 gram[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601245 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | >95% |

| Metabolism | Liver (cytosolic enzymes and glucuronic acid) |

| Elimination half-life | 1–5 hours (healthy adults) |

| Excretion | Kidney (<1%)[3] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H12N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 252.273 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Oxcarbazepine, sold under the brand name Trileptal among others, is a medication used to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder.[1] For epilepsy it is used for both focal seizures and generalized seizures.[5] It has been used both alone and as add-on therapy in people with bipolar who have had no success with other treatments.[6][1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, double vision and trouble with walking.[2] Serious side effects may include anaphylaxis, liver problems, pancreatitis, suicide, and an abnormal heart beat.[2][5] While use during pregnancy may harm the baby, use may be less risky than having a seizure.[7] Use is not recommended during breastfeeding.[7] In those with an allergy to carbamazepine there is a 25% risk of problems with oxcarbazepine.[2] How it works is not entirely clear.[1]

Oxcarbazepine was patented in 1969 and came into medical use in 1990.[8] It is available as a generic medication.[5] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £6.50 as of 2019.[5] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about $7.15.[9] In 2017, it was the 207th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[10][11]

Medical uses

Oxcarbazepine is an anticonvulsant used to reduce the occurrence of epileptic episodes, and is not intended to cure epilepsy.[12] Oxcarbazepine is used alone or in combination with other medications for the treatment of focal (partial) seizures in adults.[2] In pediatric populations, it can be used by itself for the treatment of partial seizures for children 4 years and older, or in combination with other medications for children 2 years and older.[2]

Research has investigated the use of oxcarbazepine as a mood stabilizer in bipolar disorder, with further evidence needed to fully assess its suitability.[6][13][14][15] It may be beneficial in trigeminal neuralgia.[16]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 1 gram by mouth.[4]

Side effects

Side effects are dose dependent. The most common include dizziness, blurred or double vision, nystagmus, ataxia, fatigue, headaches, nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, difficulty in concentration and mental sluggishness.[2]

Other rare side effects of oxcarbazepine include severe low blood sodium (hyponatremia), anaphylaxis / angioedema, hypersensitivity (especially if experienced with carbamazepine), toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and thoughts of suicide.[2]

Measurement of serum sodium levels should be considered in maintenance treatment or if symptoms of hyponatremia develop.[2] Low blood sodium is seen in 20-30% of people taking oxcarbazepine and 8-12% of those experience severe hyponatremia. Some side effects, such as headaches, are more pronounced shortly after a dose is taken and tend to fade with time (60 to 90 minutes). Other side effects include stomach pain, tremor, rash, diarrhea, constipation, decreased appetite and dry mouth. Photosensitivity is a potential side-effect and people could experience severe sunburns as a result of sun exposure.[2]

Pregnancy

Oxcarbazepine is listed as pregnancy category C.[2]

There is limited data analyzing the impact of oxcarbazepine on a human fetus.[2] Animal studies have shown an increased fetal abnormalities in pregnant rats and rabbits exposed to oxcarbazepine during pregnancy.[2] In addition, oxcarbazepine is structurally similar to carbamazepine, which is considered to be teratogenic in humans (pregnancy category D).[2][17] Oxcarbazepine should only be used during pregnancy if the benefits justify the risks.[2]

Pregnant persons on oxcarbazepine should be closely monitored, as plasma levels of the active metabolite licarbazepine have been shown to potentially decrease during pregnancy.[2]

Breastfeeding

Oxcarbazepine and its metabolite licarbazepine are both present in human breast milk and thus, some of the active drug can be transferred to a nursing infant.[2] When considering whether to continue this medication in nursing mothers, the impact of the drug's side effect profile on the infant, should be weighed against its anti-epileptic benefit for the mother.[2]

Interactions

Oxcarbazepine, licarbazepine and many other common drugs influence each other through interaction with the Cytochrome P450 family of enzymes. This leads to a cluster of dozens of common drugs interacting with one another to varying degrees, some of which are especially noteworthy:

Oxcarbazepine and licarbazepine are potent inhibitors of CYP2C19 and thus have the potential to increase plasma concentration of drugs, which are metabolized through this pathway.[2] Other antiepileptics, which are CYP2C19 substrates and thus may be metabolised at a reduced rate when combined with oxcarbazepine include diazepam,[18][19] hexobarbital,[18] mephenytoin,[18][19] methylphenobarbital,[18] nordazepam,[19] phenobarbital,[18] phenytoin,[19] primidone.[18] However, many classes of drugs are ligands to CYP2C19.

In addition, oxcarbazepine and licarbazepine are CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 inducers and thus have the potential to decrease the plasma concentration of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 substrates.[2] Drugs which are CYP3A4 or CYP3A5 substrates and therefore may have reduced efficacy include calcium channel antagonists against high blood pressure and oral contraceptives.[2][12] However, whether the extent of CYP3A4/5 induction at therapeutic doses reaches clinical significance is unclear.[2] Furthermore, for example phenytoin and phenobarbital are known to reduce plasma levels of licarbazepine through induction of Cytochrome P450 enzymes.[2]

Pharmacology

Oxcarbazepine is a prodrug, which is largely metabolised to its pharmacologically active 10-monohydroxy derivative licarbazepine (sometimes abbreviated MHD).[2][20] Oxcarbazepine and MHD exert their action by blocking voltage-sensitive sodium channels, thus leading to the stabilization of hyper-excited neural membranes, suppression of repetitive neuronal firing and diminishment propagation of synaptic impulses.[2] Furthermore, anticonvulsant effects of these compounds could be attributed to enhanced potassium conductance and modulation of high-voltage activated calcium channels.[2]

Pharmacokinetics

Oxcarbazepine has high bioavailability upon oral administration.[2] In a study in humans, only 2% of oxcarbazepine remained unchanged, 70% were reduced to licarbazepine; the rest were minor metabolites.[2] The half-life of oxcarbazepine is considered to be about 2 hours, whereas licarbazepine has a half-life of nine hours. Through its chemical difference to carbamazepine metabolic epoxidation is avoided, reducing hepatic risks.[21] Licarbazepine is metabolised by conjugation with Glucuronic acid. Approximately 4% are oxidised to the inactive 10,11-dihydroxy derivative. Elimination is almost completely renal, with faeces accounting to less than 4%. 80% of the excreted substances are to be attributed to licarbazepine or its glucuronides.

Pharmacodynamics

Both oxcarbazepine and licarbazepine were found to show anticonvulsant properties in seizure models done on animals.[2] These compounds had protective functions whenever tonic extension seizures were induced electrically, but such protection was less apparent whenever seizures were induced chemically.[2] There was no observable tolerance during a four weeks course of treatment with daily administration of oxcarbazepine or licarbazepine in electroshock test on mice and rats.[2] Most of the antiepileptic activity can be attributed to licarbazepine.[2] Aside from its reduction in side effects, it is presumed to have the same main mechanism as carbamazepine, sodium channel inhibition, and is generally used to treat the same conditions.

Pharmacogenetics

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele B*1502 has been associated with an increased incidence of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in people treated with carbamazepine, and thus those treated with oxcarbazepine might have similar risks.[2] People of Asian descent are more likely to carry this genetic variant, especially some Malaysian populations, Koreans (2%), Han Chinese (2–12%), Indians (6%), Thai (8%), and Philippines (15%).[2] Therefore, it has been suggested to consider genetic testing in these people prior to initiation of treatment.[2]

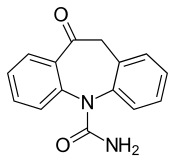

Structure

Oxcarbazepine is a structural derivative of carbamazepine, with a ketone in place of the carbon–carbon double bond on the dibenzazepine ring at the 10 position (10-keto). This difference helps reduce the impact on the liver of metabolizing the drug, and also prevents the serious forms of anemia or agranulocytosis occasionally associated with carbamazepine. Aside from this reduction in side effects, it is thought to have the same mechanism as carbamazepine — sodium channel inhibition (presumed to be the main mechanism of action) – and is generally used to treat the same conditions.

Oxcarbazepine is a prodrug which is activated to licarbazepine in the liver.[20]

History

First made in 1966,[21] it was patent-protected by Geigy in 1969 through DE 2011087. It was approved for use as an anticonvulsant in Denmark in 1990, Spain in 1993, Portugal in 1997, and eventually for all other EU countries in 1999. It was approved in the US in 2000.[1] In September 2010, Novartis, of which Geigy are part of its corporate roots, pleaded guilty to marketing Trileptal for the unapproved uses of neuropathic pain and bipolar disorder.[22]

There is also an extended-release formulation.[23]

Society and culture

Cost

A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £6.50 as of 2019.[5] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about $7.15.[9] In 2017, it was the 207th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[10][11]

.svg.png.webp) Oxcarbazepine costs (US)

Oxcarbazepine costs (US).svg.png.webp) Oxcarbazepine prescriptions (US)

Oxcarbazepine prescriptions (US)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Oxcarbazepine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 "DailyMed - OXCARBAZEPINE- oxcarbazepine tablet". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- 1 2 "Oxcarbazepine Drug Label". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 319–320. ISBN 9780857113382.

- 1 2 Mazza M, Di Nicola M, Martinotti G, Taranto C, Pozzi G, Conte G, Janiri L, Bria P, Mazza S (April 2007). "Oxcarbazepine in bipolar disorder: a critical review of the literature". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 8 (5): 649–56. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.5.649. PMID 17376019.

- 1 2 "Oxcarbazepine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 532. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- 1 2 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Oxcarbazepine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Oxcarbazepine (By mouth) - National Library of Medicine - PubMed Health". mmdn/DNX1023. Archived from the original on 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Vasudev, Akshya; MacRitchie, Karine; Vasudev, Kamini; Watson, Stuart; Geddes, John; Young, Allan H. (2011-09-02). "Oxcarbazepine for acute affective episodes of bipolar disorder". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD004857. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004857.pub2. PMID 22161387. Archived from the original on 2018-12-05. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ↑ Gitlin, Michael; Frye, Mark A (2012-05-01). "Maintenance therapies in bipolar disorders". Bipolar Disorders. 14: 51–65. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00992.x. ISSN 1399-5618. PMID 22510036.

- ↑ Reinares, María; Rosa, Adriane R.; Franco, Carolina; Goikolea, José Manuel; Fountoulakis, Kostas; Siamouli, Melina; Gonda, Xenia; Frangou, Sophia; Vieta, Eduard (2013-03-01). "A systematic review on the role of anticonvulsants in the treatment of acute bipolar depression". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 16 (2): 485–496. doi:10.1017/s1461145712000491. ISSN 1461-1457. PMID 22575611.

- ↑ Cruccu G, Gronseth G, Alksne J, Argoff C, Brainin M, Burchiel K, Nurmikko T, Zakrzewska JM (October 2008). "AAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia management". European Journal of Neurology. 15 (10): 1013–28. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02185.x. PMID 18721143.

- ↑ "DailyMed - CARBAMAZEPINE- carbamazepine tablet CARBAMAZEPINE- carbamazepine tablet, chewable". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Flockhart, DA (2007). "Drug Interactions: Cytochrome P450 Drug Interaction Table". Indiana University School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Sjöqvist, Folke. "Fakta för förskrivare: Interaktion mellan läkemedel" [Facts for prescribers: Interaction between drugs]. FASS Vårdpersonal (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 11 June 2002. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - 1 2 Dulsat, C., Mealy, N., Castaner, R., Bolos, J. (2009). "Eslicarbazepine acetate". Drugs of the Future. 34 (3): 189. doi:10.1358/dof.2009.034.03.1352675.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Shorvon, Simon D. (2009-03-01). "Drug treatment of epilepsy in the century of the ILAE: The second 50 years, 1959–2009". Epilepsia. 50: 93–130. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02042.x. ISSN 1528-1167. PMID 19298435.

- ↑ "Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. to Pay More Than $420 Million to Resolve Off-label Promotion and Kickback Allegations | OPA | Department of Justice". www.justice.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-11-07. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ↑ "Neurology Portfolio | Supernus Pharmaceuticals". www.supernus.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |