Protriptyline

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vivactyl, others |

| Other names | Amimethyline; Protriptyline hydrochloride; MK-240 |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA)[1] |

| Main uses | Depression[1] |

| Side effects | Anxiety, dizziness, dry mouth, fast heart rate, blurry vision, constipation[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604025 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 77–93%[2] |

| Protein binding | 92%[2] |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 54–92 hours |

| Excretion | Urine: 50%[2] Feces: minor[2] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H21N |

| Molar mass | 263.384 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Protriptyline, sold under the brand name Vivactil among others, is a medication used to treat depression.[1] While it has been used for obstructive sleep apnea it has not been found useful for this.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include anxiety, dizziness, dry mouth, fast heart rate, blurry vision, and constipation.[1] Other side effects may include psychosis, mania, sunburns, and suicide.[1] Safety in pregnancy and breastfeeding is unclear.[3] It is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA).[1]

Protriptyline was approved for medical use in the United States in 1967.[1] In the United States 60 tablets of 10 mg costs about 80 USD as of 2021.[4] As of 2000 it is no longer commercially available in Australia or the United Kingdom.[5]

Medical uses

Protriptyline is used primarily to treat depression and to treat the combination of symptoms of anxiety and depression.[6] Like TCAs, protriptyline has also been used in limited numbers of people to treat panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, enuresis, eating disorders such as bulimia nervosa, cocaine dependency, and the depressive phase of bipolar disorder (manic-depressive) disorder. It has also been used to support smoking cessation programs.[7]

Dosage

Protriptyline is available as 5 mg and 10 mg tablets.[8] Doses range from 15 to 40 mg per day and can be taken in one daily dose or divided into up to four doses daily.[8] Some people may require up to 60 mg per day.[8]

In adolescents and people over age 60, therapy should be initiated at a dose of 5 mg three times a day and increased as needed.[8] People over age 60 who are taking daily doses of 20 mg or more should be closely monitored for side effects such as rapid heart rate and urinary retention.[8]

Contraindications

Protriptyline may increase heart rate and stress on the heart.[9] It may be dangerous for people with cardiovascular disease, especially those who have recently had a heart attack, to take this drug or other antidepressants in the same pharmacological class.[9] In rare cases in which patients with cardiovascular disease must take protriptyline, they should be monitored closely for cardiac rhythm disturbances and signs of cardiac stress or damage.[9]

When protriptyline is used to treat the depressive component of schizophrenia, psychotic symptoms may be aggravated. Likewise, in manic-depressive psychosis, depressed patients may experience a shift toward the manic phase if they are treated with an antidepressant drug. Paranoid delusions, with or without associated hostility, may be exaggerated.[8] In any of these circumstances, it may be advisable to reduce the dose of protriptyline or to use an antipsychotic drug concurrently.[8]

Side effects

Protriptyline shares side effects common to all TCAs.[6] The most frequent of these are dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, increased heart rate, sedation, irritability, decreased coordination, anxiety, blood disorders, confusion, decreased libido, dizziness, flushing, headache, impotence, insomnia, low blood pressure, nightmares, rapid or irregular heartbeat, rash, seizures, sensitivity to sunlight, stomach and intestinal problems.[8] Other more complicated side effects include; chest pain or heavy feeling, pain spreading to the arm or shoulder, nausea, sweating, general ill feeling; sudden numbness or weakness, especially on one side of the body; sudden headache, confusion, problems with vision, speech, or balance; hallucinations, or seizure (convulsions); easy bruising or bleeding, unusual weakness; restless muscle movements in your eyes, tongue, jaw, or neck; urinating less than usual or not at all; extreme thirst with headache, nausea, vomiting, and weakness; or feeling light-headed or fainting.[8]

Dry mouth, if severe to the point of causing difficulty speaking or swallowing, may be managed by dosage reduction or temporary discontinuation of the drug.[6] Patients may also chew sugarless gum or suck on sugarless candy in order to increase the flow of saliva. Some artificial saliva products may give temporary relief.[6] Men with prostate enlargement who take protriptyline may be especially likely to have problems with urinary retention.[8] Symptoms include having difficulty starting a urine flow and more difficulty than usual passing urine.[8] In most cases, urinary retention is managed with dose reduction or by switching to another type of antidepressant.[8] In extreme cases, patients may require treatment with bethanechol, a drug that reverses this particular side effect.[8]

A common problem with TCAs is sedation (drowsiness, lack of physical and mental alertness), but protriptyline is considered the least sedating agent among this class of agents.[10] Its side effects are especially noticeable early in therapy.[10] In most people, early TCA side effects decrease or disappear entirely with time, but, until then, patients taking protriptyline should take care to assess which side effects occur in them and should not perform hazardous activities requiring mental acuity or coordination.[11] Protriptyline may increase the possibility of having seizures.[11]

Care should be taken in persons with glaucoma, especially angle-closure glaucoma (the most severe form) or urinary retention, for men with benign prostatic hypertrophy (enlarged prostate gland), and for the elderly.[10]

Withdrawal

Though not indicative of addiction, abrupt cessation of treatment after prolonged therapy may produce nausea, headache, and malaise.[9]

List of side effects

Cardiovascular: Myocardial infarction; stroke; heart block; arrhythmias; hypotension, particularly orthostatic hypotension; hypertension; tachycardia; palpitation.[12]

Psychiatric: Confusional states (especially in the elderly) with hallucinations, disorientation, delusions, anxiety, restlessness, agitation; hypomania; exacerbation of psychosis; insomnia, panic, and nightmares.[6]

Neurological: Seizures; incoordination; ataxia; tremors; peripheral neuropathy; numbness, tingling, and paresthesias of extremities; extrapyramidal symptoms; drowsiness; dizziness; weakness and fatigue; headache; syndrome of inappropriate ADH (antidiuretic hormone) secretion; tinnitus; alteration in EEG patterns.[6]

Anticholinergic: Paralytic ileus; hyperpyrexia; urinary retention, delayed micturition, dilatation of the urinary tract; constipation; blurred vision, disturbance of accommodation, increased intraocular pressure, mydriasis; dry mouth and rarely associated sublingual adentitis.[6]

Allergic: Drug fever; petechiae, skin rash, urticaria, itching, photosensitization (avoid excessive exposure to sunlight); edema (general, or of face and tongue).[6]

Hematologic: Agranulocytosis; bone marrow depression; leukopenia;thrombocytopenia; purpura; eosinophilia.[6]

Gastrointestinal: Nausea and vomiting; anorexia; epigastric distress; diarrhea; peculiar taste; stomatitis; abdominal cramps; black tongue.[6]

Endocrine: Impotence, increased or decreased libido: gynecomastia in the male; breast enlargement and galactorrhea in the female; testicular swelling; elevation or depression of blood sugar levels.[6]

Other: Jaundice (simulating obstructive); altered liver function; parotid swelling; alopecia; flushing; weight gain or loss; urinary frequency, nocturia; perspiration.[6]

Overdose

Deaths may occur from overdose with this class of drugs.[11] Multiple drug ingestion (including alcohol) is common in deliberate TCA overdose.[11] As management of overdose is complex and changing, it is recommended that the physician contact a poison control center for current information on treatment.[6] Signs and symptoms of toxicity develop rapidly after TCA overdose, therefore, hospital monitoring is required as soon as possible.[11]

Critical manifestations of overdose include: cardiac dysrhythmias, severe hypotension, convulsions, and CNS depression, including coma.[8] Changes in the electrocardiogram, particularly in QRS axis or width, are clinically significant indicators of TCA toxicity.[8] Other signs of overdose may include: confusion, disturbed concentration, transient visual hallucinations, dilated pupils, agitation, hyperactive reflexes, stupor, drowsiness, muscle rigidity, vomiting, hypothermia, hyperpyrexia.[8]

Interactions

The side effects of protriptyline are increased when it is taken with central nervous system depressants, such as alcoholic beverages, sleeping medications, other sedatives, or antihistamines, as well as with other antidepressants including SSRIs, SNRIs or monoamine oxidase inhibitors.[11] It may be dangerous to take protriptyline in combination with these substances.[11]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 19.6 | Human | [14] |

| NET | 1.41 | Human | [14] |

| DAT | 2,100 | Human | [14] |

| 5-HT1A | 3,800 | Human | [15] |

| 5-HT2A | 70 | Human | [15] |

| 5-HT2C | ND | ND | ND |

| α1 | 130 | Human | [16] |

| α2 | 6,600 | Human | [16] |

| β | >10,000 | Monkey/rat | [17] |

| D2 | 2,300 | Human | [16] |

| H1 | 7.2–25 | Human | [18][16] |

| H2 | 398 | Human | [18] |

| H3 | >100,000 | Human | [18] |

| H4 | 15,100 | Human | [18] |

| mACh | 25 | Human | [16][19] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Protriptyline acts by decreasing the reuptake of norepinephrine and to a lesser extent serotonin (5-HT) in the brain.[9] Its affinity for the human norepinephrine transporter (NET) is 1.41 nM, 19.6 nM for the serotonin transporter and 2,100 nM for the dopamine transporter.[20] TCAs act to change the balance of naturally occurring chemicals in the brain that regulate the transmission of nerve impulses between cells. Protriptyline increases the concentration of norepinephrine and serotonin (both chemicals that stimulate nerve cells) and, to a lesser extent, blocks the action of another brain chemical, acetylcholine.[9] The therapeutic effects of protriptyline, like other antidepressants, appear slowly. Maximum benefit is often not evident for at least two weeks after starting the drug.[9]

Protriptyline is a TCA.[8] It was thought that TCAs work by inhibiting the reuptake of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin by neurons.[8] However, this response occurs immediately, yet mood does not lift for around two weeks.[8] It is now thought that changes occur in receptor sensitivity in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus.[8] The hippocampus is part of the limbic system, a part of the brain involved in emotions. TCAs are also known as effective analgesics for different types of pain, especially neuropathic or neuralgic pain.[8] A precise mechanism for their analgesic action is unknown, but it is thought that they modulate anti-pain opioid systems in the central nervous system via an indirect serotonergic route. TCAs are also effective in migraine prophylaxis, but not in abortion of acute migraine attack.[8] The mechanism of their anti-migraine action is also thought to be serotonergic, similar to psilocybin.[8]

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolic studies indicate that protriptyline is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and is rapidly sequestered in tissues.[6] Relatively low plasma levels are found after administration, and only a small amount of unchanged drug is excreted in the urine of dogs and rabbits.[6] Preliminary studies indicate that demethylation of the secondary amine moiety occurs to a significant extent, and that metabolic transformation takes place in the liver.[6] It penetrates the brain rapidly in mice and rats, and moreover that which is present in the brain is almost all unchanged drug.[6] Studies on the disposition of radioactive protriptyline in human test subjects showed significant plasma levels within 2 hours, peaking at 8 to 12 hours, then declining gradually.[6]

Urinary excretion studies in the same subjects showed significant amounts of radioactivity in 2 hours.[6] The rate of excretion was slow.[6] Cumulative urinary excretion during 16 days accounted for approximately 50% of the drug. The fecal route of excretion did not seem to be important.[6]

Protriptyline has uniquely low dosing among TCAs, likely due to its exceptionally long terminal half-life.[21] It is used in dosages of 15 to 40 mg/day, whereas most other TCAs are used at dosages of 75 to 300 mg/day.[21] The maximum dose is 60 mg/day.[21] Therapeutic levels of protriptyline are typically in the range of 70 to 250 ng/mL (266-950 nmol/L), which is similar to that of other TCAs[22][23][24]

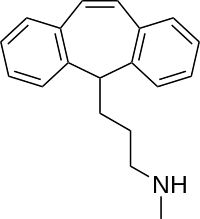

Chemistry

Protriptyline is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzocycloheptadiene, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[25] Other dibenzocycloheptadiene TCAs include amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and butriptyline.[25][26] Protriptyline is a secondary amine TCA, with its N-methylated relative amitriptyline being a tertiary amine.[27][28] Other secondary amine TCAs include desipramine and nortriptyline.[29][30] The chemical name of protriptyline is 3-(5H-dibenzo[a,d][7]annulen-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C19H21N1 with a molecular weight of 263.377 g/mol.[31] The drug is used commercially mostly as the hydrochloride salt; the free base form is not used.[31][32] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 438-60-8 and of the hydrochloride is 1225-55-4.[31][32]

History

Protriptyline was developed by Merck.[33] It was patented in 1962 and first appeared in the literature in 1964.[33] The drug was first introduced for the treatment of depression in 1966.[33][34]

Society and culture

Generic names

Protriptyline is the English and French generic name of the drug and its INN, BAN, and DCF, while protriptyline hydrochloride is its USAN, USP, and BANM.[31][32][35][36] Its generic name in Spanish and Italian and its DCIT are protriptylina, in German is protriptylin, and in Latin is protriptylinum.[32][36]

Brand names

Protriptyline is or has been marketed throughout the world under a variety of brand names including Anelun, Concordin, Maximed, Triptil, and Vivactil.[31][32]

Availability

The sale of protriptyline was discontinued in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Ireland in 2000.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Protriptyline Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 588–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ↑ "Protriptyline (Vivactil) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ "Protriptyline Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- 1 2 "Protriptyline". web.archive.org. NHS. 20 August 2013. Archived from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 DURAMED PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., . (Ed.). (2007). Protriptyline drug facts. Pomona, New York : Barr Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

- ↑ ULTRAM, . (Ed.). (2007). Protriptyline. Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. AHFS Drug Information 2002. Bethesda: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, 2002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Advameg, Inc. (2010). Protriptyline Archived 2020-08-14 at the Wayback Machine at MindDisorders.com

- 1 2 3 Kirchheiner, J; Nickchen, K; Bauer, M; Wong, M-L; Licinio, J; Roots, I; Brockmöller, J (May 2004). "Pharmacogenetics of antidepressants and antipsychotics: the contribution of allelic variations to the phenotype of drug response". Mol. Psychiatry. 9 (5): 442–73. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001494. PMID 15037866.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 DeVane, C. Lindsay, Pharm.D. "Drug Therapy for Mood Disorders." In Fundamentals of Monitoring Psychoactive Drug Therapy. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1990.

- ↑ Sériès F, Cormier Y (October 1990). "Effects of protriptyline on diurnal and nocturnal oxygenation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Ann. Intern. Med. 113 (7): 507–11. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-7-507. PMID 2393207.

- ↑ Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- 1 2 Wander TJ, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E (1986). "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 132 (2–3): 115–21. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richelson E, Nelson A (1984). "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 230 (1): 94–102. PMID 6086881.

- ↑ Bylund DB, Snyder SH (1976). "Beta adrenergic receptor binding in membrane preparations from mammalian brain". Mol. Pharmacol. 12 (4): 568–80. PMID 8699.

- 1 2 3 4 Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2): 145–70. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803. S2CID 14274150.

- ↑ El-Fakahany E, Richelson E (1983). "Antagonism by antidepressants of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors of human brain". Br. J. Pharmacol. 78 (1): 97–102. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1983.tb17361.x. PMC 2044798. PMID 6297650.

- ↑ "PDSP Database - UNC". PDSP Ki Database. University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 Stephen M. Stahl (31 March 2017). Prescriber's Guide: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 619–. ISBN 978-1-108-22874-9. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ↑ Anne M Van Leeuwen; Mickey Lynn Bladh (19 February 2016). Textbook of Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing: Practical Application of Nursing Process at the Bedside. F.A. Davis. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-8036-5845-5. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ↑ Louis A. Pagliaro; Ann M. Pagliaro (1999). Psychologists' Psychotropic Drug Reference. Psychology Press. pp. 545–. ISBN 978-0-87630-964-3. Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- ↑ Alan F. Schatzberg; Charles B. Nemeroff (2009). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9. Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- 1 2 Michael S Ritsner (15 February 2013). Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ↑ Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 580–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- ↑ Neal R. Cutler; John J. Sramek; Prem K. Narang (20 September 1994). Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ↑ Pavel Anzenbacher; Ulrich M. Zanger (23 February 2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ↑ Patricia K. Anthony (2002). Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-56053-470-9. Archived from the original on 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- ↑ Philip Cowen; Paul Harrison; Tom Burns (9 August 2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. p. 1040. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 894–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- 1 2 3 Andersen J, Kristensen AS, Bang-Andersen B, Strømgaard K (2009). "Recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of antidepressant drugs with serotonin and norepinephrine transporters". Chem. Commun. (25): 3677–92. doi:10.1039/b903035m. PMID 19557250.

- ↑ Richard C. Dart (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 836–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ↑ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- 1 2 "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2017-08-17. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|